AI-Driven Behavioral Data Analysis: Machine Learning Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in behavioral data analysis for biomedical research and drug development.

AI-Driven Behavioral Data Analysis: Machine Learning Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in behavioral data analysis for biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational ML concepts for researchers, detailed methodologies for behavioral analysis in preclinical studies, optimization techniques for robust model performance, and validation frameworks for regulatory compliance. With case studies from neuroscience research and drug discovery, we demonstrate how ML accelerates the analysis of complex behaviors, enhances predictive accuracy in therapeutic development, and enables more efficient translation of research findings into clinical applications.

From Raw Data to Actionable Insights: Defining the Scope of ML in Behavioral Analysis

Understanding Behavioral Data Types in Biomedical Research

Behavioral data encompasses the actions and behaviors of individuals that are relevant to health and disease. In biomedical research, this includes both overt behaviors (directly measurable actions like physical activity or verbal responses) and covert behaviors (activities not directly viewable, such as physiological responses like heart rate) [1]. The precise classification and measurement of these behaviors are fundamental to developing effective machine learning (ML) models for tasks such as predictive health monitoring, personalized intervention, and drug efficacy testing.

Behavioral informatics, an emerging transdisciplinary field, combines system-theoretic principles with behavioral science and information technology to optimize interventions through monitoring, assessing, and modeling behavior [1]. This guide provides detailed protocols for classifying behavioral data, preparing it for analysis, and applying machine learning algorithms to advance research in this domain.

Classification and Presentation of Behavioral Data

Proper classification and presentation of data are critical first steps in any analysis. Behavioral data can be broadly divided into categorical and numerical types [2].

Categorical Behavioral Variables

Categorical or qualitative variables describe qualities or characteristics and are subdivided as follows [2]:

- Dichotomous (Binary) Variables: Have only two categories (e.g., "Yes" or "No" for treatment response, "Male" or "Female").

- Nominal Variables: Have three or more categories without an inherent order (e.g., blood types A, B, AB, O; primary method of communication).

- Ordinal Variables: Have three or more categories with a logical sequence or order (e.g., Fitzpatrick skin types I-V, frequency of a behavior categorized as "Never," "Rarely," "Sometimes," "Often").

Protocol 2.1.1: Presenting Categorical Variables in a Frequency Table

Objective: To synthesize the distribution of a categorical variable into a clear, self-explanatory table.

- Count Observations: Tally the number of observations (n) falling into each category of the variable.

- Calculate Relative Frequencies: For each category, calculate the percentage (%) that its count represents of the total number of observations.

- Construct the Table:

- Number the table (e.g., Table 1).

- Provide a clear, concise title that identifies the variable and population.

- Use clear column headings (e.g., Category, Absolute Frequency (n), Relative Frequency (%)).

- List categories in a logical order (e.g., ascending, descending, or alphabetically).

- Include a row for the total count (100%) [3] [2].

Table 1: Example Frequency Table for a Categorical Variable (Presence of Acne Scars)

| Prevalence | Absolute Frequency (n) | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No | 1855 | 76.84 |

| Yes | 559 | 23.16 |

| Total | 2414 | 100.00 |

Numerical Behavioral Variables

Numerical or quantitative variables represent measurable quantities and are subdivided into:

- Discrete Variables: Can only take specific numerical values, often counts (e.g., number of times a patient visited a clinician in a year, number of compulsive behaviors in an hour) [2].

- Continuous Variables: Can take any value within a given range and are measured on a continuous scale (e.g., reaction time, blood pressure, heart rate, age in years with decimals) [2].

Protocol 2.2.1: Grouping Continuous Data into Class Intervals for a Histogram

Objective: To transform a continuous variable into a manageable number of categories for visual presentation in a histogram, which is a graphical representation of the frequency distribution [4].

- Calculate the Range: Subtract the smallest observed value from the largest observed value.

- Determine the Number of Classes: Choose a number of class intervals (k) typically between 5 and 16 [3] [4].

- Calculate Class Width: Divide the range by the number of classes (k). Round up to a convenient number.

- Define Intervals: Create non-overlapping intervals of equal size that cover the entire range from the minimum to the maximum value. The intervals should be continuous (touching without gaps) [4].

- Count Frequencies: Tally the number of observations falling into each class interval.

Table 2: Example Frequency Distribution for a Continuous Variable (Weight in Pounds)

| Class Interval | Absolute Frequency (n) |

|---|---|

| 120 – 134 | 4 |

| 135 – 149 | 14 |

| 150 – 164 | 16 |

| 165 – 179 | 28 |

| 180 – 194 | 12 |

| 195 – 209 | 8 |

| 210 – 224 | 7 |

| 225 – 239 | 6 |

| 240 – 254 | 2 |

| 255 – 269 | 3 |

Experimental Protocols for Machine Learning with Behavioral Data

Applying ML to behavioral data involves a structured process from data preparation to model evaluation.

Protocol: A Checklist for Rigorous ML Experimentation

Objective: To provide a systematic framework for designing, executing, and analyzing machine learning experiments that yield reliable and reproducible results [5].

- State the Objective: Clearly define the experiment's goal and a meaningful effect size (e.g., "Determine if data augmentation improves model accuracy by at least 5%") [5].

- Select the Response Function: Choose the primary metric to maximize or minimize (e.g., classification accuracy, mean squared error, F1-score) [5].

- Identify Variable and Fixed Factors: Decide which factors will vary (e.g., model type, hyperparameters, feature sets) and which will remain constant [5].

- Describe a Single Run: Define one instance of the experiment, including the specific configuration of factors and the datasets used for training, validation, and testing to prevent data contamination [5].

- Choose an Experimental Design:

- Factor Space: Plan how to explore different factor combinations (e.g., grid search, random search for hyperparameters).

- Cross-Validation: Implement a scheme (e.g., k-fold cross-validation) to reduce variance from data splitting and generate robust performance estimates [5].

- Perform the Experiment: Use experiment tracking tools to log parameters, code versions, and results for reproducibility [6] [5].

- Analyze the Data: Evaluate results using cross-validation averages, error bars, and statistical hypothesis testing to determine if observed differences are significant [5].

- Draw Conclusions: State conclusions backed by the data analysis, ensuring they are reproducible by other researchers [5].

Protocol: Applying ML to a Small Behavioral Dataset

Objective: To demonstrate the end-to-end application of a machine learning algorithm to a small behavioral dataset for classification, using a study on an interactive web training for parents of children with autism as an example [7].

- Data Preparation and Feature Selection:

- Dataset: 26 parent-child dyads (samples) [7].

- Features (Discriminative Stimuli): Select variables with high correlation to the outcome and no multicollinearity. In this example, features are household income (dichotomized), parent's most advanced degree (dichotomized), child's social functioning, and baseline score on parental use of behavioral interventions [7].

- Class Label (Correct Response): A binary outcome indicating whether the child's challenging behavior decreased post-training (0 = no improvement, 1 = improvement) [7].

- Algorithm Selection and Training: Choose one or more supervised learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, k-Nearest Neighbors). The algorithm trains a model to learn the relationship between the features and the class label [7].

- Model Evaluation: Use techniques like cross-validation on this dataset to assess the model's ability to predict the outcome for new, unseen samples [7].

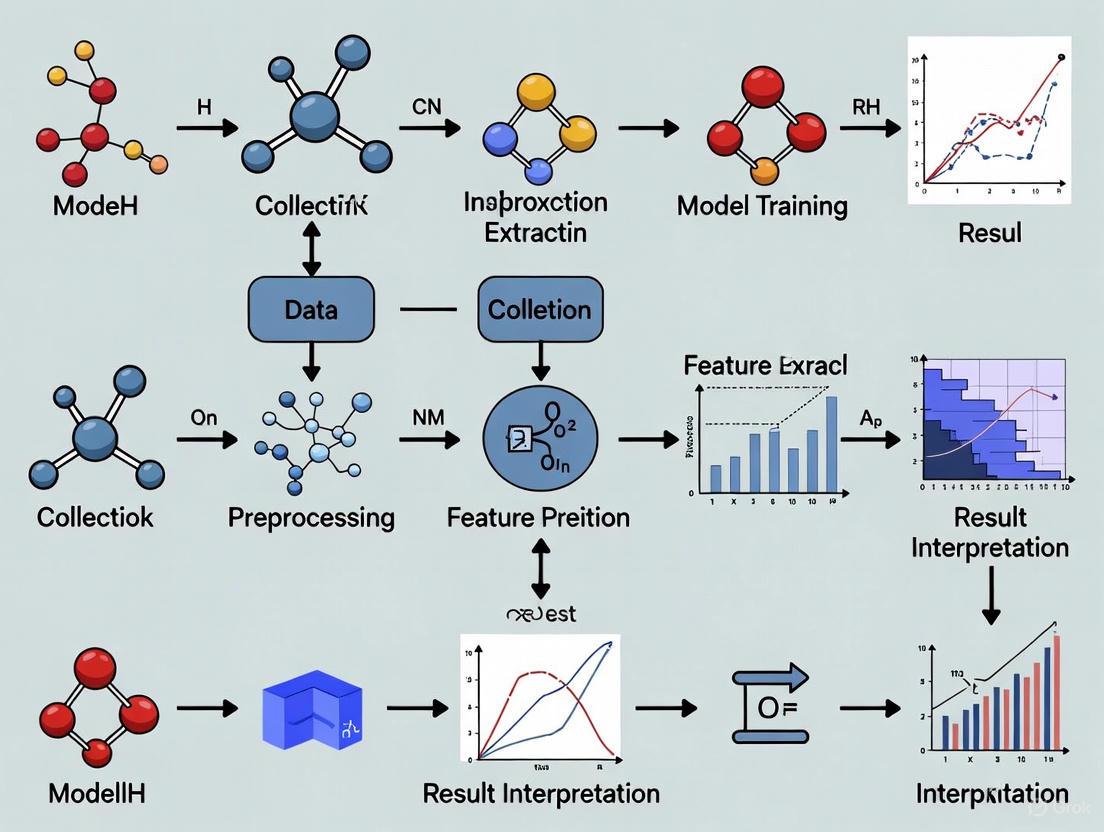

ML Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key components used in the acquisition and analysis of behavioral data.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Behavioral Informatics Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Wearable Sensors (Accelerometers, Gyroscopes, HR Monitors) | Capture overt motor activities (e.g., physical movement) and covert physiological responses (e.g., heart rate) in real-time, "in the wild" [1]. |

| Environmental Sensors (PIR, Contact Switches, 3-D Cameras) | Monitor subject location, movement patterns within a space, and interaction with objects, providing context for behavior [1]. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | A research method that collects real-time data on behaviors and subjective states in a subject's natural environment, often via smartphone [1]. |

| Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention (JITAI) | A closed-loop intervention framework that uses sensor data and computational models to deliver tailored support at the right moment [1]. |

| Health Coaching Platform | A semi-automated system that integrates sensor data, a dynamic user model, and a message database to facilitate remote, personalized health behavior interventions [1]. |

| Random Forest / SVM / k-NN Algorithms | Supervised machine learning algorithms used to train predictive models on behavioral datasets, even with a relatively small number of samples (e.g., n=26) [7]. |

| Experiment Tracking Tools | Software to systematically log parameters, metrics, code, and environment details across hundreds of ML experiments, ensuring reproducibility [6] [5]. |

Data Visualization and Signaling Pathways

Effective visualization is key to understanding data distributions and analytical workflows.

Behavioral Data Classification

Core Machine Learning Concepts for Behavioral Scientists

Machine learning (ML), a subset of artificial intelligence, provides computational methods that automatically find patterns and relationships in data [8]. For behavioral scientists, this represents a paradigm shift, enabling the analysis of complex behavioral phenomena—from individual cognitive processes to large-scale social interactions—through a data-driven lens [8]. The application of ML in behavioral research accelerates the discovery of subtle patterns that may elude traditional analytical methods, particularly as theories become richer and more complex [9].

Behavioral data, whether from wearable sensors, experimental observations, or clinical assessments, is often high-dimensional and temporal. ML algorithms are exceptionally suited to extract meaningful signals from this complexity, offering tools to react to behaviors in real-time, understand underlying processes, and document behaviors for future analysis [8]. This article outlines core ML concepts and provides practical protocols for integrating these powerful methods into behavioral research.

Core Machine Learning Types and Algorithms

Machine learning approaches can be categorized based on the learning paradigm and the nature of the problem. The table below summarizes the three primary types.

Table 1: Core Types of Machine Learning

| Learning Type | Definition | Common Algorithms | Behavioral Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Uses labeled data to develop predictive models. The algorithm learns from historical data where the correct outcome is known [10] [11]. | Linear & Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naïve Bayes [10] [11] | Predicting treatment outcomes, classifying behavioral functions (e.g., attention, escape), identifying mental health states from sensor data [7]. |

| Unsupervised Learning | Identifies hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in unlabeled data [10]. | K-Means Clustering, Hierarchical Clustering, C-Means (Fuzzy Clustering) [10] | Discovering novel behavioral phenotypes, segmenting patient populations, identifying co-occurring behavioral patterns without pre-defined categories [10]. |

| Reinforcement Learning | An agent learns to make decisions by performing actions and receiving rewards or penalties from its environment [10]. | Q-Learning, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) | Optimizing adaptive behavioral interventions, modeling learning processes in decision-making tasks [9]. |

The Machine Learning Workflow in Behavioral Research

A standardized workflow is crucial for developing robust ML models. The following diagram illustrates the key stages, from data preparation to model deployment, in a behavioral research context.

Application Note: Predicting Intervention Efficacy

Protocol: Predicting Response to a Behavioral Intervention

This protocol is adapted from a tutorial applying ML to predict which parents of children with autism spectrum disorder would benefit from an interactive web training to manage challenging behaviors [7].

Objective: To build a classification model that predicts whether a parent-child dyad will show a reduction in challenging behaviors post-intervention.

Dataset Preparation

- Samples: 26 parents who completed the training.

- Features: Four key variables were used as input features (discriminative stimuli).

- Household income (dichotomized)

- Parent's most advanced degree (dichotomized)

- Child's social functioning

- Baseline score of parental use of behavioral interventions

- Class Label: Binary outcome indicating whether the child's challenging behavior decreased from baseline to a 4-week posttest (0 = no improvement, 1 = improvement) [7].

Table 2: Example Dataset for Predicting Intervention Efficacy

| Household Income | Most Advanced Degree | Child's Social Functioning | Baseline Intervention Score | Class Label (Improvement) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | High | 45 | 15 | 1 |

| Low | High | 52 | 18 | 1 |

| High | Low | 38 | 9 | 0 |

| Low | Low | 41 | 11 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Methodology

- Data Preprocessing: Dichotomize skewed ordinal variables to create more balanced categories. Check for and address multicollinearity among features.

- Model Training & Evaluation:

- Algorithm Selection: Apply algorithms suitable for small datasets, such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Stochastic Gradient Descent, and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [7].

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate performance using a confusion matrix to calculate metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall. The confusion matrix is structured as:

- True Positive (TP): Correctly predicted positive cases.

- False Positive (FP): Incorrectly predicted positive cases.

- False Negative (FN): Missed positive cases.

- True Negative (TN): Correctly predicted negative cases [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for ML in Behavioral Science

| Item/Software | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Python/R Programming Environment | Provides the core computational environment for data manipulation, analysis, and implementing ML algorithms. | Using scikit-learn in Python to train a Random Forest model. |

| Wearable Sensors (Accelerometer, GSR) | Capture raw behavioral and physiological data from participants in naturalistic settings [8]. | Collecting movement data to automatically detect physical activity or agitation levels. |

| Bio-logging Devices | Record behavioral data from animals or humans over extended periods for later analysis [8]. | Tracking the flight behavior of birds to understand movement patterns with minimal human intervention. |

| Simulator Models | Formalize complex theories about latent psychological processes to generate quantitative predictions about observable behavior [9]. | Simulating data from a decision-making model to test hypotheses that are difficult to assess with living organisms. |

Advanced Concepts: Optimizing Behavioral Experiments

Bayesian Optimal Experimental Design (BOED) is a powerful framework that uses machine learning to design maximally informative experiments [9]. This is particularly valuable for discriminating between competing computational models of cognition or for efficient parameter estimation.

Concept: BOED reframes experimental design as an optimization problem. The researcher specifies controllable parameters of an experiment (e.g., stimuli, rewards), and the framework identifies the settings that maximize a utility function, such as expected information gain [9].

Workflow: The process involves simulating data from computational models of behavior (simulator models) for different potential experimental designs and selecting the design that is expected to yield the most informative data for the scientific question at hand [9]. The relationships between the computational models, the experimental design, and the data are shown below.

Application: BOED can be used to design optimal decision-making tasks (e.g., multi-armed bandits) that most efficiently determine which model best explains an individual's behavior or that best characterize their model parameters [9]. Compared to conventional designs, optimal designs require fewer trials to achieve the same statistical confidence, reducing participant burden and resource costs.

Data Visualization and Accessibility for Behavioral Data

Effectively communicating the results of ML analysis is a critical final step. Adhering to accessibility guidelines ensures that visualizations are inclusive and that their scientific message is clear to all readers [12].

Key Principles for Accessible Visualizations:

- Color and Contrast: Do not rely on color alone to convey meaning. Use patterns, shapes, or direct labels as additional visual indicators. Ensure text has a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 against the background, and adjacent data elements (e.g., bar graph segments) have a 3:1 contrast ratio [12].

- Labeling and Descriptions: Provide clear titles, axis labels, and legends. Use "direct labeling" where possible, placing labels adjacent to data points. All visualizations must include alternative text (alt text) that succinctly describes the key finding of the chart [12].

- Supplemental Data: Provide the underlying data in a tabular format (e.g., CSV file) to accommodate different analytical preferences and ensure access for users with visual impairments [12].

The field of behavioral analysis is undergoing a profound transformation, evolving from labor-intensive manual scoring methods to sophisticated, data-driven automated systems powered by machine learning (ML). This shift is critically enhancing the objectivity, scalability, and informational depth of behavioral phenotyping in preclinical and clinical research. Within drug discovery and development, automated ML-based analysis accelerates the identification of novel therapeutic candidates and improves the predictive validity of behavioral models for human disorders [13] [14]. These Application Notes and Protocols detail the implementation of automated ML pipelines, providing researchers with standardized methodologies to quantify complex behaviors, integrate multimodal data, and translate findings into actionable insights for pharmaceutical development.

Traditional manual scoring of behavior, while foundational, is inherently limited by low throughput, subjective bias, and an inability to capture the full richness of nuanced, high-dimensional behavioral states. The integration of machine learning addresses these constraints by enabling the continuous, precise, and unbiased quantification of behavior from video, audio, and other sensor data [15]. This evolution is pivotal for translational medicine, as it forges a more reliable bridge between preclinical models and clinical outcomes. In the pharmaceutical industry, the application of ML extends across the value chain—from initial target identification and validation to the design of more efficient clinical trials [14]. By providing a more granular and objective analysis of drug effects on behavior, these technologies are poised to reduce attrition rates and foster the development of more effective neurotherapeutics and personalized medicine approaches.

The impact of ML on behavioral analysis and the broader drug discovery pipeline can be quantified in terms of market growth, application efficiency, and algorithmic preferences. The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from current market analyses and research trends.

Table 1: Machine Learning in Drug Discovery Market Overview (2024-2034)

| Parameter | 2024 Market Share / Status | Projected Growth / Key Trends |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Leadership | North America (48% revenue share) [15] | Asia Pacific (Fastest-growing region) [15] |

| Leading Application Stage | Lead Optimization (~30% share) [15] | Clinical Trial Design & Recruitment (Rapid growth) [15] |

| Dominant Algorithm Type | Supervised Learning (40% share) [15] | Deep Learning (Fastest-growing segment) [15] |

| Preferred Deployment Mode | Cloud-based (70% revenue share) [15] | Hybrid Deployment (Rapid expansion) [15] |

| Key Therapeutic Area | Oncology (~45% share) [15] | Neurological Disorders (Fastest-growing) [15] |

Table 2: Performance and Impact Metrics of ML in Research

| Metric Category | Findings | Implication for Behavioral Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency & Cost | AI/ML can significantly shorten development timelines and reduce costs [13] [14]. | Enables high-throughput screening of behaviors, reducing manual scoring time. |

| Data Processing Speed | AI can analyze vast datasets much faster than conventional approaches [15]. | Allows for continuous analysis of long-term behavioral recordings. |

| Adoption & Trust | Implementing robust ethical AI guidelines can increase public trust by up to 40% [16]. | Supports the credibility and acceptance of automated behavioral phenotyping. |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Driven Behavioral Analysis

Protocol: Video-Based Pose Estimation and Feature Extraction for Rodent Behavior

Objective: To automatically quantify postural dynamics and locomotor activity from video recordings of rodents in an open-field test, extracting features for subsequent behavioral classification.

Materials:

- High-speed camera (e.g., 30-100 fps) with consistent, diffuse lighting.

- Standard rodent open-field arena.

- Computer with GPU for deep learning model inference.

- Software: DeepLabCut, SLEAP, or similar pose estimation tool [14].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Record videos of subjects in the arena. Ensure minimal background noise and consistent lighting.

- Model Training:

- Labeling: Manually annotate a representative subset of video frames (100-200) with key body points (e.g., nose, ears, tail base, paws).

- Training: Train a convolutional neural network (CNN) on the labeled frames to predict the (x, y) coordinates of each keypoint on new, unlabeled videos.

- Evaluation: Validate the model's performance on a held-out test set of frames, ensuring low pixel error.

- Pose Estimation & Tracking: Process all experimental videos with the trained model to generate trajectory data for each keypoint across time and for each individual animal.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate a set of quantitative features from the pose data, including:

- Kinematic Features: Velocity, acceleration, angular velocity of the body center.

- Postural Features: Distances between body parts, body elongation, angles at joints.

- Spatial Features: Time spent in center vs. periphery, path complexity.

Deliverable: A time-series dataset of engineered features for each subject, ready for behavioral classification.

Protocol: Supervised Classification of Discrete Behavioral States

Objective: To train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) to identify discrete, ethologically relevant behaviors (e.g., rearing, grooming, digging) from extracted pose features.

Materials:

- Feature dataset from Protocol 3.1.

- Software: Python (with scikit-learn, XGBoost libraries) or R.

Methodology:

- Ground Truth Labeling: Using a tool like BORIS, manually annotate the start and end times of target behaviors in the videos based on expert-defined criteria.

- Data Alignment & Windowing: Align the ground truth labels with the corresponding time-series feature data. Segment the data into fixed-length time windows.

- Model Training:

- Feature Selection: Use feature importance scores (e.g., from a Random Forest) to select the most discriminative features for each behavior.

- Classifier Training: Train a supervised learning algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) using the selected features and ground truth labels. Employ k-fold cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters.

- Model Validation:

- Evaluate classifier performance on a completely held-out test dataset using metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy.

- Generate a confusion matrix to identify specific behaviors the model confuses.

Deliverable: A validated, trained model capable of automatically scoring behavioral bouts with high reliability from new pose data.

Workflow Visualization

ML-Driven Behavioral Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Automated Behavioral Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DeepLabCut | Open-source toolbox for markerless pose estimation based on transfer learning. | Extracts 2D or 3D body keypoint coordinates from video (Protocol 3.1) [14]. |

| BORIS | Free, open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. | Creates the ground truth labels required for supervised classifier training (Protocol 3.2). |

| scikit-learn | Comprehensive Python library featuring classic ML algorithms and utilities. | Implements data preprocessing, feature selection, and classifier models like Random Forests (Protocol 3.2). |

| Cloud Computing Platform | Provides scalable computational resources (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud). | Handles resource-intensive model training and large-scale data processing, especially for deep learning [15]. |

| GPU-Accelerated Workstation | Local computer with a high-performance graphics card. | Enables efficient pose estimation model training and inference on local data (Protocol 3.1). |

Key Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Discovery

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is instigating a paradigm shift in neuroscience research and therapeutic development [17] [18]. These technologies are moving beyond theoretical promise to become tangible forces, compressing traditional discovery timelines that have long relied on cumbersome trial-and-error approaches [17]. By leveraging predictive models and generative algorithms, researchers can now decipher the complexities of neural systems and accelerate the journey from target identification to clinical candidate, marking a fundamental transformation in modern pharmacology and neurobiology [17] [19]. This document details specific applications, protocols, and resources underpinning this transformation, providing a framework for the implementation of AI-driven strategies in research and development.

Quantitative Landscape of AI-Discovered Therapeutics

The impact of AI is quantitatively demonstrated by the growing pipeline of AI-discovered therapeutics entering clinical trials. By the end of 2024, over 75 AI-derived molecules had reached clinical stages, a significant leap from virtually zero in 2020 [17]. The table below summarizes key clinical-stage candidates, highlighting the compression of early-stage development timelines.

Table 1: Selected AI-Discovered Drug Candidates in Clinical Development

| Company/Platform | Drug Candidate | Indication | AI Application & Key Achievement | Clinical Stage (as of 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insilico Medicine | ISM001-055 | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | Generative AI for target discovery and molecule design; progressed from target to Phase I in 18 months [17]. | Phase IIa (Positive results reported) [17] |

| Exscientia | DSP-1181 | Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) | First AI-designed drug to enter a Phase I trial (2020) [17]. | Phase I (Program status post-merger not specified) |

| Schrödinger | Zasocitinib (TAK-279) | Inflammatory Diseases (e.g., psoriasis) | Physics-enabled design strategy; originated from Nimbus acquisition [17]. | Phase III [17] |

| Exscientia | GTAEXS-617 (CDK7 inhibitor) | Solid Tumors | AI-designed compound; part of post-2023 strategic internal focus [17]. | Phase I/II [17] |

| Exscientia | EXS-74539 (LSD1 inhibitor) | Oncology | AI-designed compound [17]. | Phase I (IND approved in 2024) [17] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Leading AI Drug Discovery Platforms

| AI Platform | Core Technological Approach | Representative Clinical Asset | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Chemistry (e.g., Exscientia) | Uses deep learning on chemical libraries to design novel molecular structures satisfying target product profiles (potency, selectivity, ADME) [17]. | DSP-1181, EXS-21546 | In silico design cycles ~70% faster and requiring 10x fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [17]. |

| Phenomics-First Systems (e.g., Recursion) | Leverages high-content phenotypic screening in cell models, often using patient-derived biology, to generate vast datasets for AI analysis [17]. | Portfolio from merger with Exscientia | Integrated platform generates extensive phenomic and biological data for validation [17]. |

| Physics-plus-ML Design (e.g., Schrödinger) | Combines physics-based molecular simulations with machine learning for precise molecular design and optimization [17]. | Zasocitinib (TAK-279) | Platform enabled advancement of TYK2 inhibitor to late-stage clinical testing [17]. |

| Knowledge-Graph Repurposing (e.g., BenevolentAI) | Applies AI to mine complex relationships from scientific literature and databases to identify new targets or new uses for existing drugs [17]. | Not specified in search results | Aids in hypothesis generation for target discovery and drug repurposing [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven Discovery

Protocol: AI-Driven Target Discovery and Validation for Neurological Disorders

Objective: To identify and prioritize novel therapeutic targets for a complex neurological disease (e.g., Alzheimer's) using a knowledge-graph and genomics AI platform.

Materials:

- AI Platform: BenevolentAI or similar knowledge-graph-driven platform [17].

- Data Inputs: Public and proprietary datasets including genomic data (e.g., GWAS, single-cell RNA-seq from post-mortem brain tissue), scientific literature corpus, and protein-protein interaction networks.

- Validation Reagents: Cell culture materials (primary neurons or glial cells), transfection reagents, qPCR system, antibodies for Western blot/immunocytochemistry, siRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 components for gene knockdown/knockout.

Procedure:

- Data Integration and Hypothesis Generation:

- Feed integrated multi-omics data and literature into the AI platform.

- The platform's algorithms will mine the knowledge graph to identify and rank potential causal genes and proteins implicated in the disease pathology [17].

- Output: A prioritized list of novel, high-confidence candidate targets.

In Silico Validation:

- Analyze the association of candidate targets with relevant disease-associated biological pathways (e.g., neuroinflammation, synaptic plasticity).

- Assess the "druggability" of the target protein using structure-based prediction tools.

Experimental Validation (In Vitro):

- Gene Modulation: Knock down or overexpress the candidate target gene in a relevant neural cell model using siRNA or plasmid transfection.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure downstream effects on key disease-relevant phenotypes:

- Viability: Using assays like MTT or CellTiter-Glo.

- Inflammatory Markers: Quantify secretion of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) via ELISA.

- Neurite Outgrowth: Perform high-content imaging and analysis in neuronal cell models.

- A successful validation is confirmed when modulation of the target significantly alters the disease phenotype in the predicted manner.

Protocol: Generative AI for Lead Compound Optimization

Objective: To accelerate the optimization of a hit compound into a lead candidate with improved potency and desirable pharmacokinetic properties.

Materials:

- AI Platform: Exscientia's Centaur Chemist platform or similar generative chemistry system [17].

- Initial Compound: A confirmed hit compound from a high-throughput screen.

- Target Product Profile (TPP): A defined set of criteria including IC50/EC50, selectivity indices, and ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) properties.

- Automated Chemistry & Assay Systems: Robotics for compound synthesis and plating, high-throughput screening systems for potency and cytotoxicity assays.

Procedure:

- Platform Training and Setup:

- Train the generative AI models on vast chemical libraries and structure-activity relationship (SAR) data relevant to the target.

- Input the TPP as the design objective for the AI [17].

Generative Design Cycle:

- The AI proposes novel molecular structures predicted to meet the TPP.

- Output: A virtual library of thousands of designed molecules.

In Silico Prioritization:

- Apply predictive filters (e.g., for synthetic accessibility, predicted toxicity, PAINS) to rank and select a shortlist of several hundred compounds for synthesis.

Automated Synthesis and Testing (Make-Test):

- Synthesize the top-priority compounds using automated, robotics-mediated precision chemistry [17].

- Test the synthesized compounds in a battery of automated in vitro assays:

- Potency Assay (e.g., enzyme inhibition/binding assay).

- Selectivity Panel against related targets.

- Early ADME/Tox: e.g., microsomal stability, Caco-2 permeability, hERG liability.

Machine Learning Feedback Loop:

- The experimental data from synthesized and tested compounds are fed back into the AI model.

- The model learns from this new data and initiates a new, improved design cycle.

- This iterative process (design-make-test-analyze) continues until a compound meeting all TPP criteria is identified as the lead candidate [17].

Visualization of AI-Driven Workflows

Phenomics-First AI Screening Workflow

This diagram illustrates the high-throughput, data-driven workflow for identifying drug candidates based on phenotypic changes in cellular models.

Integrated AI Drug Discovery Pipeline

This diagram outlines the end-to-end, iterative process from target identification to lead candidate optimization, integrating multiple AI approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and computational tools used in AI-driven neuroscience and drug discovery research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Discovery

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge-Graph Platforms | AI-driven mining of scientific literature and databases to generate novel target hypotheses and identify drug repurposing opportunities [17]. | BenevolentAI platform; used for identifying hidden relationships in complex biological data [17]. |

| Generative Chemistry AI | Uses deep learning models trained on chemical libraries to design novel, optimized molecular structures that meet a specific Target Product Profile [17]. | Exscientia's "Centaur Chemist" platform; integrates AI design with automated testing [17]. |

| Phenotypic Screening Platforms | High-content imaging and analysis of cellular phenotypes in response to genetic or compound perturbations, generating vast datasets for AI analysis [17]. | Recursion's phenomics platform; often uses patient-derived cell models for translational relevance [17]. |

| Physics-Based Simulation Software | Provides high-accuracy predictions of molecular interactions, binding affinities, and properties by solving physics equations, often enhanced with machine learning [17]. | Schrödinger's computational platform; used for structure-based drug design [17]. |

| Patient-Derived Cellular Models | Provide biologically relevant and translatable experimental systems for target validation and compound efficacy testing, crucial for a "patient-first" strategy [17]. | e.g., primary neurons, glial cells, or iPSC-derived neural cells; Exscientia acquired Allcyte to incorporate patient tissue samples into screening [17]. |

| Automated Synthesis & Testing | Robotics and automation systems that physically synthesize AI-designed compounds and run high-throughput biological assays, closing the "Design-Make-Test" loop [17]. | Exscientia's "AutomationStudio"; integrated with AWS cloud infrastructure for scalability [17]. |

Essential Tools and Frameworks for Getting Started

Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized the analysis of behavioral data, providing researchers with powerful tools to probe the algorithms underlying behavior, find neural correlates of computational variables, and better understand the effects of drugs, illness, and interventions [20]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the right frameworks and adhering to robust experimental protocols is paramount to generating meaningful, reproducible results. This guide provides a detailed overview of the essential tools, frameworks, and methodologies required to embark on ML projects for behavioral data analysis, with a particular emphasis on applications in drug discovery and development. The adoption of these tools allows for the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best practice evidence in making decisions, which is the cornerstone of evidence-based practice [21].

Essential Machine Learning Frameworks and Tools

The landscape of machine learning tools can be divided into several key categories, from low-level programming frameworks to high-level application platforms. The choice of framework often depends on the specific task, whether it's building a deep neural network for complex pattern recognition or applying a classical algorithm to structured, tabular data.

Core Modeling Frameworks

Table 1: Core Machine Learning Frameworks for Behavioral Research

| Framework | Primary Use Case | Key Features | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch [22] [23] | Research, prototyping, deep learning | Dynamic computation graph, Pythonic syntax | High flexibility, excellent for RNNs & reinforcement learning, easy debugging [23] | Slower deployment vs. competitors, limited mobile deployment [23] |

| TensorFlow [22] [23] | Large-scale production ML, deep learning | Static computation graph (with eager execution), TensorBoard visualization | High scalability, strong deployment tools (e.g., TensorFlow Lite), vast community [22] [23] | Steep learning curve, complex debugging [23] |

| Scikit-learn [22] [23] | Classical ML on structured/tabular data | Unified API for algorithms, data preprocessing, and model evaluation | User-friendly, superb documentation, wide range of classic ML algorithms [22] [23] | No native deep learning or GPU support [23] |

| JupyterLab [23] | Interactive computing, EDA, reproducible research | Notebook structure combining code, text, and visualizations | Interactive interface, supports multiple languages, excellent for collaboration [23] | Not suited for production pipelines, version control can be challenging [23] |

AI Agent Frameworks for Workflow Automation

AI agent frameworks can significantly streamline ML operations by handling repetitive tasks and dynamic decision-making. These are particularly useful for maintaining long-term research projects and production systems.

Table 2: AI Agent Frameworks for ML Workflow Automation

| Framework | Ease of Use | Coding Required | Key Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n8n [24] | Easy | Low/Moderate | Visual workflows with code flexibility | Rapid prototyping of data pipelines and model monitoring |

| LangChain/LangGraph [24] | Advanced | High | Flexibility for experimental, stateful workflows | ML researchers building complex, multi-step experiments |

| AutoGen [24] | Advanced | High | Collaborative multi-agent systems | Sophisticated experiments with specialized agents for data prep, training, and evaluation |

| Flowise [24] | Easy | None | No-code visual interface | Rapid prototyping and involving non-technical stakeholders |

Data Analysis and Platform Tools

Table 3: Data Analysis and End-to-End Platform Tools

| Tool | Type | Key AI/ML Features | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domo [25] | End-to-end data platform | AI-enhanced data exploration, intelligent chat for queries, pre-built models for forecasting | Comprehensive data journey management with built-in governance |

| Microsoft Power BI [25] | Business Intelligence | Integration with Azure Machine Learning, AI visualization | Creating interactive reports and dashboards within the Microsoft ecosystem |

| Tableau [25] | Business Intelligence | Tableau GPT and Pulse for natural language queries and smart insights | Advanced visualizations and enterprise-grade business intelligence |

| Amazon SageMaker [23] | ML Platform | Fully managed service for building, training, and deploying models | End-to-end ML workflow in the AWS cloud |

Experimental Protocols for Behavioral Data Modeling

Computational modeling of behavioral data involves using mathematical models to make sense of observed behaviors, such as choices or reaction times, by linking them to experimental variables and underlying algorithmic hypotheses [20]. The following protocols ensure rigorous and reproducible modeling.

Protocol: Computational Modeling of Behavioral Data

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying computational models to behavioral data, from experimental design to model interpretation.

1. Experimental Design

- Rule 1: Design a good experiment. The experimental protocol must be rich enough to engage the targeted cognitive processes and allow for the identification of the computational variables of interest. Computational modeling cannot compensate for a poorly designed experiment [20].

- Rule 2: Define the scientific question. Clearly articulate the cognitive process or aspect of behavior you are targeting (e.g., "How does working memory contribute to learning?"). This guides the entire modeling process [20].

- Rule 3: Seek model-independent signatures. The best experiments are those where signatures of the targeted computations are also evident in simple, classical analyses of the behavioral data. This builds confidence that the modeling process will be informative [20].

2. Model Selection and Fitting

- Rule 4: Simulate before fitting. Always simulate data from your model with known parameters before applying it to real data. This "fake-data check" verifies that your model can produce the patterns you are interested in and that your fitting procedure can recover the known parameters [20].

- Rule 5: Begin with simple models. Start with the simplest possible model that captures the core theory. This establishes a baseline for performance and interpretability. Complexity can be added later if necessary [20].

- Rule 6: Use multiple optimization runs. When estimating parameters, run your optimization algorithm from multiple different starting points. This helps avoid local minima and ensures you find the best possible parameter estimates for a given model and dataset [20].

3. Model Comparison and Validation

- Rule 7: Validate model comparison. Use methods like cross-validation to assess how well your model will generalize to new data, rather than relying solely on metrics like BIC or AIC that are calculated on the training data. This provides a more robust measure of a model's quality [20].

- Rule 8: Do not rely on a single measure of fit. Compare models using multiple metrics and criteria. A model might be best according to one metric but perform poorly on another, such as its ability to predict new data versus its complexity [20].

- Rule 9: Check model mimicry. Be aware that models with different underlying mechanisms can sometimes produce highly similar data. Simulate from competing models to see if your model comparison method can correctly distinguish between them [20].

4. Interpretation and Inference

- Rule 10: Interpret parameters with caution. A model parameter is an estimate, not a direct measurement of a psychological process. Its value can be influenced by other parameters in the model, the task design, and individual differences. Always report parameter estimates with measures of uncertainty [20].

Figure 1: A workflow for the computational modeling of behavioral data, outlining the ten simple rules from experimental design to interpretation.

Protocol: Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART)

The SMART design is an experimental approach specifically developed to inform the construction of high-quality adaptive interventions (also known as dynamic treatment regimens), which are crucial in behavioral medicine and drug development.

1. Purpose and Rationale

- Adaptive interventions operationalize a sequence of decision rules that specify how intervention options should be adapted to an individual's characteristics and changing needs over time [21].

- SMART designs are used to address research questions that inform the construction of these decision rules, such as comparing the effects of different intervention options at critical decision points [21].

2. Key Design Features

- Sequential Randomization: Participants are randomized multiple times throughout the trial at critical decision points. The second (or subsequent) randomization can be tailored based on the participant's response or adherence to the first-stage intervention.

- Replication of Decision Points: The design replicates the sequential decision-making process that occurs in clinical practice, allowing investigators to study the effects of different adaptive intervention strategies embedded within the trial.

3. Implementation Steps

- Step 1: Define the Decision Points. Identify the key stages in the intervention process where a decision about adapting the treatment (e.g., intensifying, switching, or maintaining) is required.

- Step 2: Specify Tailoring Variables. Define the variables (e.g., early response, side-effect burden, adherence level) that will be used to guide the adaptation decision at each stage.

- Step 3: Randomize at First Stage. Randomize all eligible participants to the available first-stage intervention options.

- Step 4: Assess and Re-randomize. At the next decision point, assess the tailoring variables and then re-randomize participants to the second-stage options. This re-randomization can be common to all or depend on the first-stage intervention and/or the value of the tailoring variable.

- Step 5: Analyze and Construct. Analyze the data to compare the sequences of interventions (i.e., the embedded adaptive interventions) and construct the optimal intervention strategy.

Figure 2: A SMART design flowchart showing sequential randomization based on treatment response.

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

Machine learning methods are increasingly critical in addressing the long timelines, high costs, and enormous uncertainty associated with drug discovery and development [26] [27]. The following section details specific applications and a novel methodology.

Key Drug Development Tasks and ML Solutions

Table 4: ML Applications in Key Drug Development Tasks

| Drug Development Task | Description | Relevant ML Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Prediction &\nDe Novo Drug Design [26] | Designing novel molecular structures from scratch that are chemically correct and have desired properties. | Generative Models (VAE, GAN), Reinforcement Learning [26] |

| Molecular Property Prediction [26] | Identifying therapeutic effects, potency, bioactivity, and toxicity from molecular data. | Deep Representation Learning, Graph Embeddings, Random Forest [26] [27] |

| Virtual Drug Screening [26] | Predicting how drugs bind to target proteins and affect their downstream activity. | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naive Bayesian (NB), Knowledge Graph Embeddings [26] [27] |

| Drug Repurposing [26] | Finding new therapeutic uses for existing or novel drugs. | Knowledge Graph Embeddings, Similarity-based ML [26] |

| Adverse Effect Prediction [26] | Predicting adverse drug effects, drug-drug interactions (polypharmacy), and drug-food interactions. | Graph-based ML, Active Learning [26] |

Protocol: SPARROW for Cost-Aware Molecule Downselection

The SPARROW (Synthesis Planning and Rewards-based Route Optimization Workflow) framework is an algorithmic approach designed to automatically identify optimal molecular candidates by minimizing synthetic cost while maximizing the likelihood of desired properties [28].

1. Problem Definition

- Objective: Select a batch of molecules for synthesis and testing that optimizes the trade-off between expected scientific value and synthetic cost, considering shared intermediates and common experimental steps.

- Input: A set of candidate molecules (hand-designed, from catalogs, or AI-generated) and a definition of the desired properties [28].

2. Data Collection and Integration

- Step 1: Gather Molecular Data. SPARROW collects information on the candidate molecules and their potential synthetic pathways from online repositories and AI tools.

- Step 2: Calculate Utility. For each molecule, a utility score is estimated based on its predicted properties and the uncertainty of those predictions.

- Step 3: Calculate Cost. The framework estimates the cost of synthesizing each molecule, capturing shared costs for molecules that can be derived from common chemical compounds and intermediate steps [28].

3. Batch Optimization

- Step 4: Optimize Batch. The algorithm performs a unified optimization to select the best subset of candidates. It considers the marginal cost of adding each new molecule to the batch, which depends on the molecules already chosen due to shared synthesis paths [28].

- Output: The framework outputs the optimal subset of molecules to synthesize and the most cost-effective synthetic routes for that specific batch [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Databases and Tools for ML-Driven Drug Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [27] | Database | Encompassing information on chemicals and their biological activities. | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| DrugBank [27] | Database | Detailed drug data and drug-target information. | http://www.drugbank.ca |

| ChEMBL [27] | Database | Drug-like small molecules with predicted bioactive properties. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| BRENDA [27] | Database | Comprehensive enzyme and enzyme-ligand information. | http://www.brenda-enzymes.org |

| Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) [27] | Database | Information on drug targets, resistance mutations, and target combinations. | http://bidd.nus.edu.sg/group/ttd/ttd.asp |

| ADReCS [27] | Database | Toxicology information with over 137,000 Drug-Adverse Drug Reaction pairs. | http://bioinf.xmu.edu.cn/ADReCS |

| GoPubMed [27] | Text-Mining Tool | A specialized PubMed search engine used for text-mining and literature analysis. | http://www.gopubmed.org |

| SPARROW [28] | Algorithmic Framework | Identifies optimal molecules for testing by balancing synthetic cost and expected value. | N/A (Methodology) |

Figure 3: The SPARROW framework for cost-aware molecule downselection, integrating multiple data sources to optimize batch synthesis.

Implementing ML Pipelines for Behavioral Phenotyping and Drug Efficacy Studies

The integration of machine learning (ML) with multimodal data collection is revolutionizing behavioral analysis in research and drug development. By combining high-fidelity video tracking, continuous sensor data, and nuanced clinical assessments, researchers can construct comprehensive digital phenotypes of behavior with unprecedented precision. These methodologies enable the objective quantification of complex behavioral patterns, moving beyond traditional, often subjective, scoring methods to accelerate the discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic interventions [29] [30]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these core data collection strategies within an ML-driven research framework.

Video Tracking for Behavioral Analysis

Video tracking technologies have evolved from simple centroid tracking to advanced pose estimation models that capture the intricate kinematics of behavior.

Key Methodologies and Tools

Table 1: Comparison of Open-Source Pose Estimation Tools

| Tool Name | Key Features | Model Architecture | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLabCut [29] | - Markerless pose estimation- Transfer learning capability- Multi-animal tracking | Deep Neural Network (e.g., ResNet, EfficientNet) + Deconvolutional Layers | High-precision tracking in neuroscience & ethology; outperforms commercial software (EthoVision) in assays like elevated plus maze [29]. |

| SLEAP [29] | - Real-time capability- Multi-animal tracking- User-friendly interface | Deep Neural Network (e.g., ResNet, EfficientNet) + Centroid & Part Detection Heads | Social behavior analysis, real-time closed-loop experiments. |

| DeepPoseKit [29] | - Efficient inference- Integration with behavior classification | Deep Neural Network + DenseNet-style pose estimation | Large-scale behavioral screening requiring high-throughput analysis. |

Experimental Protocol: Pose Estimation for Reward-Seeking Behavior

Objective: To quantify the kinematics of reward-seeking behavior in a rodent model using markerless pose estimation, identifying movement patterns predictive of reward value or neural activity.

Materials:

- Animal subjects: Laboratory rodents (e.g., C57BL/6 mice).

- Apparatus: Operant conditioning chamber with reward ports, high-speed camera (>30 fps), and diffuse, consistent lighting.

- Software: DeepLabCut (v2.3.0 or higher) or SLEAP (v1.0 or higher), Python environment with GPU support [29].

Procedure:

- Video Acquisition:

- Position the camera orthogonally to the behavioral arena to minimize perspective distortion.

- Record a minimum of 100 frames containing the animal in diverse postures (reaching, turning, rearing) for initial model training. Ensure videos are well-lit and free from flicker.

Model Training and Validation:

- Labeling: Manually annotate body parts (e.g., snout, ears, tail base) across the collected frames to create a ground-truth dataset.

- Training: Use a pre-trained network (e.g., ResNet-50) as a feature extractor and train the model on the labeled data for approximately 200,000 iterations. Monitor training and validation loss to prevent overfitting.

- Evaluation: Apply the trained model to a new, unlabeled video. Manually check a subset of frames to ensure the average error is less than 5 pixels for each body part.

Pose Estimation and Analysis:

- Inference: Process all experimental videos through the trained model to extract time-series data of body part coordinates.

- Feature Extraction: From the pose data, calculate kinematic features such as:

- Velocity and Trajectory: of the snout and tail base.

- Head-Scanning Angle: as a measure of vicarious trial-and-error.

- Gait Dynamics: and turning patterns during approach.

Data Integration: Correlate the extracted kinematic features with simultaneous neural recordings (e.g., electrophysiology) or trial parameters (e.g., reward size) to identify neural correlates of specific movements [29].

Workflow Diagram: Video Analysis Pipeline

Video Analysis Workflow: From raw video to behavioral phenotype using pose estimation and machine learning.

Sensor Data Acquisition and Integration

Sensor-based Digital Health Technologies (DHTs) provide continuous, objective data on physiological and activity metrics directly from participants in real-world settings.

Sensor-Derived Measures and Applications

Table 2: Common Sensor-Derived Measures in Clinical Research

| Data Type | Sensor Technology | Measured Parameter | Example Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometry | Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Gait, posture, activity counts, step count | Monitoring motor function in Parkinson's disease [31] [30]. |

| Electrodermal Activity | Bioimpedance Sensor | Skin conductance | Measuring sympathetic nervous system arousal in anxiety disorders. |

| Photoplethysmography | Optical Sensor | Heart rate, heart rate variability | Assessing cardiovascular load and sleep quality. |

| Electrocardiography | Bio-potential Electrodes | Heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV) | Cardiac safety monitoring in clinical trials [31]. |

| Inertial Sensing | Gyroscope, Magnetometer | Limb kinematics, tremor, balance | Quantifying spasticity in Multiple Sclerosis. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Sensor-Based DHTs in a Clinical Trial

Objective: To passively monitor daily activity and gait quality in patients with neurodegenerative disorders using a wearable sensor, deriving digital endpoints for treatment efficacy.

Materials:

- Wearable Sensor: Research-grade wearable device (e.g., ActiGraph, Axivity) with tri-axial accelerometer and gyroscope.

- Software Platform: For data aggregation, processing, and visualization (e.g., custom cloud platform per DiMe toolkits) [32].

Procedure:

- Technology Selection and Validation:

- Select a sensor whose measurement characteristics (sampling rate, dynamic range) are fit-for-purpose for the clinical concept of interest (e.g., gait impairment) [31].

- Conduct a validation study in a small cohort to verify the device can capture the intended measures against a gold standard.

Participant Onboarding and Compliance:

- Provide participants with clear instructions and training on device use (e.g., wearing location, charging schedule).

- To optimize compliance (>75-80% is often considered good), choose an unobtrusive device, minimize participant burden, and consider roundtable discussions with patient groups during trial design [31].

Data Collection and Management:

- Deploy sensors to participants for a predefined period (e.g., 7 consecutive days at baseline and post-intervention).

- Establish a secure data flow from the device to the analysis platform. The Data Flow Design Tool from the Digital Medicine Society (DiMe) is recommended for mapping this process and ensuring data integrity [32].

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction:

- Pre-processing: Apply filters to remove noise and artifacts. Detect non-wear time.

- Feature Extraction: Use validated algorithms to extract digital measures from raw sensor data. Examples include:

- Activity Counts: and time spent in various intensity levels.

- Gait Parameters: stride length, cadence, and variability from walking bouts.

- Sleep Metrics: total sleep time, wake-after-sleep-onset.

Endpoint Development and Analysis:

- Define a digital endpoint (e.g., "mean daily step count" or "gait velocity") statistically powered to detect a change due to intervention.

- Apply machine learning models (e.g., transformer-based) to the high-dimensional sensor data for pattern recognition and prediction of disease progression [33] [30].

Clinical Assessments in a Digital Context

Clinical assessments provide the essential ground truth and contextual framework for interpreting digital data, ensuring biological and clinical relevance.

Integrating Traditional and Digital Measures

In the era of biomarkers, clinical assessment remains a "custom that should never go obsolete" [34]. It establishes the patient-physician relationship and provides a holistic understanding of the patient that biomarkers alone cannot capture. The goal is a synergistic approach where digital measures augment, not replace, clinical expertise.

Framework for Biomarker Utility: In neurodegenerative disease, a seven-level theoretical construct can guide integration [34]:

- Levels 1-3: Biomarkers support clinical assessment (e.g., increasing diagnostic confidence).

- Levels 4-7: Biomarkers may surpass clinical assessment in detecting pre-symptomatic disease or predicting pathology, yet still require clinical correlation.

Protocol: Collaborative Clinical Assessment for Interdisciplinary Teams

Objective: To leverage interdisciplinary expertise (e.g., medical and pharmacy students) for comprehensive patient assessment, optimizing diagnosis and treatment planning while reducing medical errors [35].

Procedure:

- Patient Interview and History:

- Medical Student Role: Conducts the primary patient interview, performs physical and neurological examinations, and develops a leading diagnosis.

- Pharmacy Student Role: Obtains a comprehensive medication and allergy history, assesses for drug-drug interactions, and evaluates adherence.

Data Synthesis and Diagnostic Reasoning:

- Both students collaboratively review patient history, laboratory data, and digital data streams (sensor, video).

- The medical student interprets findings within the clinical presentation, while the pharmacy student assesses the appropriateness of the current pharmacotherapy regimen relative to the diagnosis and patient factors (e.g., renal function).

Interdisciplinary Discussion and Plan Formulation:

- The team discusses the case, integrating clinical assessment findings with digital biomarker data.

- The pharmacy student provides evidence-based recommendations for medication tailoring, including alternatives for suboptimal efficacy, adverse effects, or cost.

- A final, collaborative treatment plan is documented, including monitoring parameters for both clinical and digital outcomes [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Behavioral Data Analysis Research

| Item | Function & Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DeepLabCut [29] | Open-source tool for markerless pose estimation based on transfer learning. Tracks user-defined body parts from video. | https://github.com/DeepLabCut/DeepLabCut |

| SLEAP [29] | Open-source tool for multi-animal pose tracking, designed for high-throughput and real-time use cases. | https://sleap.ai/ |

| DiMe Sensor Toolkits [32] | A suite of open-access tools for managing the flow, architecture, and standards of sensor data in research. | Sensor Data Integrations Toolkits (Digital Medicine Society) |

| Research-Grade Wearable | A body-worn sensor for continuous, passive data collection of physiological and activity metrics. | Devices from ActiGraph, Axivity; should include IMU and programmability. |

| VIA Annotator [29] | A manual video annotation tool for creating ground-truth datasets for training and validating ML models. | http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/software/via/ |

| FDA DHT Framework [36] | Guidance on the use of Digital Health Technologies in drug and biological product development. | FDA Framework for DHTs in Drug Development |

Integrated Data Analysis Workflow

The power of modern behavioral analysis lies in the strategic fusion of video, sensor, and clinical data streams.

Multimodal Data Integration Diagram

Multimodal Data Fusion: Integrating video kinematics, sensor biomarkers, and clinical scores for a holistic behavioral phenotype using machine learning.

Machine Learning Model Selection Guide

The choice of ML architecture is critical and depends on the behavioral analysis task.

Table 4: Matching Model Architecture to Behavioral Task Complexity

| Task Complexity | Recommended Architecture | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object/Presence Tracking | Detector + Tracker (e.g., YOLO + DeepSORT) [33] | Fast, suitable for real-time edge deployment. | Provides limited behavioral insight beyond location and trajectory. |

| Action Classification | CNN + RNN (e.g., ResNet + LSTM) [33] | Models temporal sequences, good for recognizing actions like walking or falling. | Sequential processing can be slower; may be surpassed by newer models on complex tasks. |

| Fine-Grained Motion | 3D CNNs (e.g., I3D, R2Plus1D) [33] | Learns motion directly from frame sequences; effective for short-range patterns. | Computationally intensive; less efficient for long-range dependencies. |

| Complex Behavior & Long-Range Context | Transformer-Based Models (e.g., ViT + Temporal Attention) [33] | Superior temporal understanding, parallel processing, scalable for complex recognition. | Requires large datasets and significant computational power. |

By implementing these detailed protocols and leveraging the recommended tools, researchers can robustly collect and integrate multimodal behavioral data, laying a solid foundation for advanced machine learning analysis and accelerating progress in behavioral research and drug development.

The analysis of behavioral data through machine learning (ML) offers unprecedented opportunities for understanding complex patterns in fields ranging from neuroscience to drug development. Behavioral data, often captured from sensors, video recordings, or digital platforms, is inherently messy and complex. Preprocessing transforms this raw, unstructured data into a refined format suitable for computational analysis, forming the critical foundation upon which reliable and valid models are built [37] [38]. The quality of preprocessing directly dictates the performance of subsequent predictive models, making it a pivotal step in the research pipeline [39]. This document outlines standardized protocols and application notes for the cleaning, normalization, and feature extraction of behavioral data, framed within a rigorous ML research context.

Data Cleaning and Imputation

Data cleaning addresses inconsistencies and missing values that invariably arise during behavioral data acquisition. The primary goals are to ensure data integrity and prepare a complete dataset for analysis.

Identification and Analysis of Missing Data

The first step involves a systematic assessment of data completeness. Tools like the naniar package in R provide functions such as gg_miss_var() to visualize which variables contain missing values and their extent [37]. Deeper exploration with functions like vis_miss() can reveal patterns of missingness—whether they are random or systematic. Systematic missingness often stems from technical specifications, such as different sensors operating at different sampling rates (e.g., an accelerometer at 200 Hz versus a pressure sensor at 25 Hz), leading to a predictable pattern of missing values in the merged data stream [37].

Imputation Techniques and Protocols

Once missing values are identified, researchers must select an appropriate imputation strategy. The choice of method depends on the nature of the data and the presumed mechanism behind the missingness.

Table 1: Standardized Protocols for Handling Missing Data

| Method | Protocol Description | Best Use Case | Considerations for Behavioral Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listwise Deletion | Complete removal of rows or columns with missing values. | When the amount of missing data is minimal and assumed to be completely random. | Not recommended for time-series behavioral data as it can disrupt temporal continuity. |

| Mean/Median Imputation | Replacing missing values with the variable's mean or median. | Simple, quick method for numerical data with a normal distribution (mean) or skewed distribution (median). | Sensitive to outliers; can reduce variance and distort relationships in the data [37] [38]. |

| Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) | Replacing a missing value with the last available value from the same variable. | Time-series data where the immediate past value is a reasonable estimate for the present. | Can introduce bias by artificially flattening variability in behaviors over time. |

| Model-Based Imputation (e.g., MICE, KNN) | Using statistical or ML models to predict missing values based on other variables in the dataset. | Datasets with complex relationships between variables; considered a more robust approach [38]. | Computationally intensive. Crucially, models must be trained only on the training set to prevent information injection and overfitting [37]. |

For implementation, the simputation package in R offers methods like impute_lm() for linear regression-based imputation [37]. In Python, scikit-learn provides functionalities for KNN imputation, while statsmodels can be used for Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) [38].

Data Transformation: Smoothing and Normalization

Transformation techniques are applied to reduce noise and ensure variables are on a comparable scale, which is essential for many ML algorithms.

Smoothing Behavioral Time-Series

Smoothing helps to highlight underlying patterns in behavioral time-series data by attenuating short-term, high-frequency noise. The Simple Moving Average is a common technique where each point in the smoothed series is the average of the surrounding data points within a window of predefined size [37]. A variation is the Centered Moving Average, which uses an equal number of points on either side of the center point, requiring an odd window size. For data with outliers, a Moving Median is more robust. The window size is a critical parameter; a window too small may not effectively reduce noise, while one too large may obscure meaningful behavioral patterns [37].

Normalization and Scaling Protocols

Normalization adjusts the scale of numerical features to a standard range, preventing variables with inherently larger ranges from dominating the model's objective function.

Table 2: Standardized Protocols for Data Normalization and Scaling

| Method | Formula | Protocol Description | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Max Scaling | ( X{\text{norm}} = \frac{X - X{\min}}{X{\max} - X{\min}} ) | Rescales features to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]. | When the data distribution does not follow a Gaussian distribution. Requires known min/max values. |

| Standardization (Z-Score) | ( X_{\text{std}} = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} ) | Rescales features to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. | When the data approximately follows a Gaussian distribution. Less affected by outliers. |

| Mean Normalization | ( X{\text{mean-norm}} = \frac{X - \mu}{X{\max} - X_{\min}} ) | Scales data to have a mean of 0 and a range of [-1, 1]. | A less common variant, useful for centering data while bounding the range. |

| Unit Vector Transformation | ( X_{\text{unit}} = \frac{X}{\lVert X \rVert} ) | Scales individual data points to have a unit norm (length of 1). | Often used in text analysis or when the direction of the data vector is more important than its magnitude. |

These transformations can be efficiently implemented using the StandardScaler (for Z-score) and MinMaxScaler classes from the scikit-learn library in Python [38].

Feature Engineering and Extraction

This phase involves creating new, informative features from raw data that are more representative of the underlying behavioral phenomena for ML models.

Creating Informative Behavioral Features

Feature engineering for behavioral data often involves generating summary statistics from raw sensor readings (e.g., accelerometer, gyroscope) over defined epochs. These can include:

- Time-domain features: Mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and correlation between axes.

- Frequency-domain features: Dominant frequencies, spectral power, and entropy derived from a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

- Custom behavioral metrics: For example, creating a feature that represents the "total activity" by integrating movement over time or calculating the variability of a physiological signal like heart rate.

The goal is to construct features that provide the model with high-quality, discriminative information about specific behaviors (e.g., grazing vs. fighting in animal models) [37].

Dimensionality Reduction

Datasets with a large number of features risk the "curse of dimensionality," which can lead to model overfitting. Dimensionality reduction techniques help mitigate this.

- Feature Selection: Selecting a subset of the most relevant features using techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or assessing feature importance from tree-based models [38].

- Feature Extraction: Transforming the original high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a linear technique that finds the directions of maximum variance in the data [39] [38]. Other methods include Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), which is supervised and seeks directions that maximize class separation.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for preprocessing behavioral data, from raw acquisition to a model-ready dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Libraries for Behavioral Data Preprocessing

| Tool / Library | Function | Application in Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| Python (Pandas, NumPy) | Programming language and core data manipulation libraries. | Loading, manipulating, and cleaning raw data frames; implementing custom imputation and transformation logic. |

| R (naniar, simputation) | Statistical programming language and specialized packages. | Advanced visualization and diagnosis of missing data patterns; performing robust model-based imputation. |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | Comprehensive machine learning library. | Standardizing data scaling (StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler), encoding categorical variables, and performing dimensionality reduction (PCA). |

| Signal Processing Toolboxes (SciPy, MATLAB) | Libraries for time-series analysis. | Applying digital filters for smoothing, performing FFT for frequency-domain feature extraction. |

| Datylon / Sigma | Data visualization and reporting tools. | Creating publication-quality charts and graphs to visualize data distributions before and after preprocessing. |

The rigorous preprocessing of behavioral data—encompassing meticulous cleaning, thoughtful transformation, and insightful feature engineering—is not merely a preliminary step but a cornerstone of robust machine learning research. The protocols and application notes detailed herein provide a standardized framework for researchers and drug development professionals to enhance the reliability, interpretability, and predictive power of their analytical models. By adhering to these practices, the scientific community can ensure that the valuable insights hidden within complex behavioral data are accurately and effectively uncovered.

Convolutional Neural Networks for Automated Behavior Classification

Automated behavior classification represents a significant frontier in machine learning research, with profound implications for neuroscience, pharmacology, and drug development. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as particularly powerful tools for this task, capable of extracting spatiotemporal features from complex behavioral data with minimal manual engineering. Unlike traditional methods that rely on hand-crafted features, CNNs can automatically learn hierarchical representations directly from raw input data, making them exceptionally suited for detecting subtle behavioral patterns that might escape human observation or conventional analysis [40] [41].