Animal Personality and Behavioral Syndromes: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of the field of animal personality, defined as consistent individual differences in behavior that are stable over time and across contexts.

Animal Personality and Behavioral Syndromes: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of the field of animal personality, defined as consistent individual differences in behavior that are stable over time and across contexts. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational theories of behavioral syndromes, established and emerging methodologies for personality assessment, and the critical challenges in data interpretation. It further examines the validation of personality traits and their comparative impact in diverse fields, including conservation translocations and biomedical research. By integrating ecological and evolutionary perspectives with biomedical applications, this review aims to establish animal personality as a crucial source of individual variation that can influence experimental outcomes, therapeutic efficacy, and the development of animal models for human conditions like Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome.

Defining the Consistent Individual: Core Concepts and Evolutionary Frameworks of Animal Personality

The study of animal personality represents a paradigm shift in behavioral ecology, moving beyond anthropomorphic interpretations to establish a rigorous biological construct. Animal personality is scientifically defined as behavioral and physiological differences between individuals of the same species that are stable in time and across different contexts [1]. This conceptual framework provides a foundation for understanding how consistent individual differences influence evolutionary processes, ecological dynamics, and conservation outcomes. The biological basis of personality transcends simple behavioral observations, encompassing correlated suites of traits known as behavioral syndromes—statistically related behaviors that occur across multiple contexts [2] [3]. This construct has revolutionized how researchers approach behavioral variation, shifting focus from population-level averages to meaningful individual differences that persist over time and circumstances.

The ontology of animal personality operates across three distinct levels: specific behaviors (observable actions), personality traits (consistent dispositions), and general personality (the overall behavioral phenotype) [4]. This hierarchical structure allows researchers to systematically investigate how discrete behaviors give rise to stable traits, which in turn form integrated behavioral profiles. The field has matured from initial documentation of individual differences to sophisticated investigations of proximate mechanisms, evolutionary consequences, and ecological implications, establishing animal personality as a legitimate biological phenomenon with far-reaching implications across disciplines from behavioral ecology to conservation science [1] [5].

Defining Criteria: The Operational Framework

The identification and validation of animal personality traits rest upon three formal criteria that must be satisfied simultaneously. These criteria provide the operational framework that distinguishes personality from transient behavioral states.

Individual Differences (Variation Between Individuals)

The foundation of personality research rests on demonstrable behavioral variation between individuals of the same species [4]. This variation must be consistent and measurable, representing true differences in behavioral tendencies rather than random fluctuations. Individuals occupy different positions along behavioral gradients, allowing researchers to classify them as relatively bolder, shyer, more aggressive, or more exploratory compared to conspecifics. These differences are quantified through standardized behavioral assays and statistical comparisons of response patterns across individuals.

Temporal Stability (Consistency Over Time)

For a behavior to qualify as a personality trait, it must demonstrate stability over a biologically relevant timeframe [4]. This temporal consistency distinguishes personality traits from ephemeral behavioral states induced by immediate circumstances. The required duration of stability varies by species and lifespan, but must encompass multiple behavioral observations separated by sufficient time to rule out short-term motivational states. Temporal stability is statistically quantified through measures of repeatability, which partition behavioral variance into within-individual and between-individual components.

Contextual Consistency (Stability Across Situations)

Personality traits must manifest consistently across different environmental contexts and situations [4]. An individual's behavioral tendency should be detectable regardless of specific circumstances, though expression may vary in magnitude. This cross-contextual stability reveals the underlying behavioral architecture that constrains plasticity and generates predictable responses to diverse ecological challenges. Contextual consistency is what distinguishes specialized general tendencies from context-specific adaptations.

Table 1: Formal Criteria for Identifying Animal Personality Traits

| Criterion | Definition | Measurement Approach | Statistical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Differences | Behavioral variation between individuals of the same species | Standardized behavioral assays across multiple individuals | Significant between-individual variance component |

| Temporal Stability | Behavioral consistency within individuals across time | Repeated measurements of same individuals over biologically relevant intervals | High repeatability estimates (intra-class correlation) |

| Contextual Consistency | Behavioral stability across different situations/environments | Testing same individuals in varied ecological contexts | Significant cross-context correlations at individual level |

Methodological Framework: Measurement and Assessment

The study of animal personality employs rigorous methodological approaches designed to quantify the three defining criteria. Two primary data collection methods dominate the field: coding and rating [4].

Behavioral Coding

Behavioral coding involves direct observation and recording of discrete, well-defined behavioral units with minimal inference [4]. Researchers establish operational definitions for specific behaviors (e.g., latency to emerge from shelter, distance maintained from predator, number of conspecifics approached) and record their frequency, duration, or intensity in standardized experimental setups. This objective approach generates quantitative data suitable for statistical analysis of individual differences and their stability. Coding requires careful experimental design to control for confounding variables and ensure behavioral measures accurately reflect the underlying traits of interest.

Behavioral Rating

Rating methods involve qualitative assessments by human observers familiar with the subjects [4]. Observers score individuals on predefined trait dimensions based on integrated knowledge of their behavioral patterns across multiple situations and time points. This approach leverages the pattern-recognition capabilities of experienced observers and can capture broad behavioral tendencies that might be missed in brief, standardized tests. However, it introduces potential observer bias and requires validation against objective behavioral measures.

Experimental Assays for Common Traits

Standardized experimental paradigms have been developed to measure specific personality traits. Boldness is frequently assessed through novel object tests, predator response assays, or emergence tests [1] [6]. Exploration is measured in novel environment tests, activity in open field trials, aggressiveness through conspecific interaction tests, and sociability via choice experiments measuring time near conspecifics versus alone [6]. These assays provide operational definitions that allow cross-species comparisons while recognizing that ecological relevance may vary across taxa.

Table 2: Standardized Methodologies for Assessing Major Personality Dimensions

| Personality Dimension | Experimental Paradigms | Primary Behavioral Measures | Ecological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boldness | Novel object test, Predator simulation, Emergence test | Latency to approach, Distance to threat, Time in shelter | Risk-taking, Predator avoidance |

| Exploration | Novel environment test, Maze exploration | Area covered, Path complexity, Information gathering | Habitat exploitation, Resource finding |

| Aggressiveness | Mirror test, Resident-intruder, Resource defense | Attack latency, Threat displays, Contest duration | Territory defense, Mating competition |

| Activity | Open field test, Home cage observation | Movement rate, Distance traveled, Resting time | Energy budget, Space use |

| Sociability | Choice test, Group observation | Proximity to conspecifics, Social initiation, Contact time | Group living, Cooperation |

Behavioral Syndromes: Integrated Trait Architectures

Behavioral syndromes represent the correlated suites of behaviors that constitute the integrated phenotype, formally defined as "a suite of correlated behaviors expressed either within a given behavioral context or across different contexts" [2]. These syndromes structure individual behavioral variation into predictable patterns that constrain independent evolution of single traits and generate ecological trade-offs.

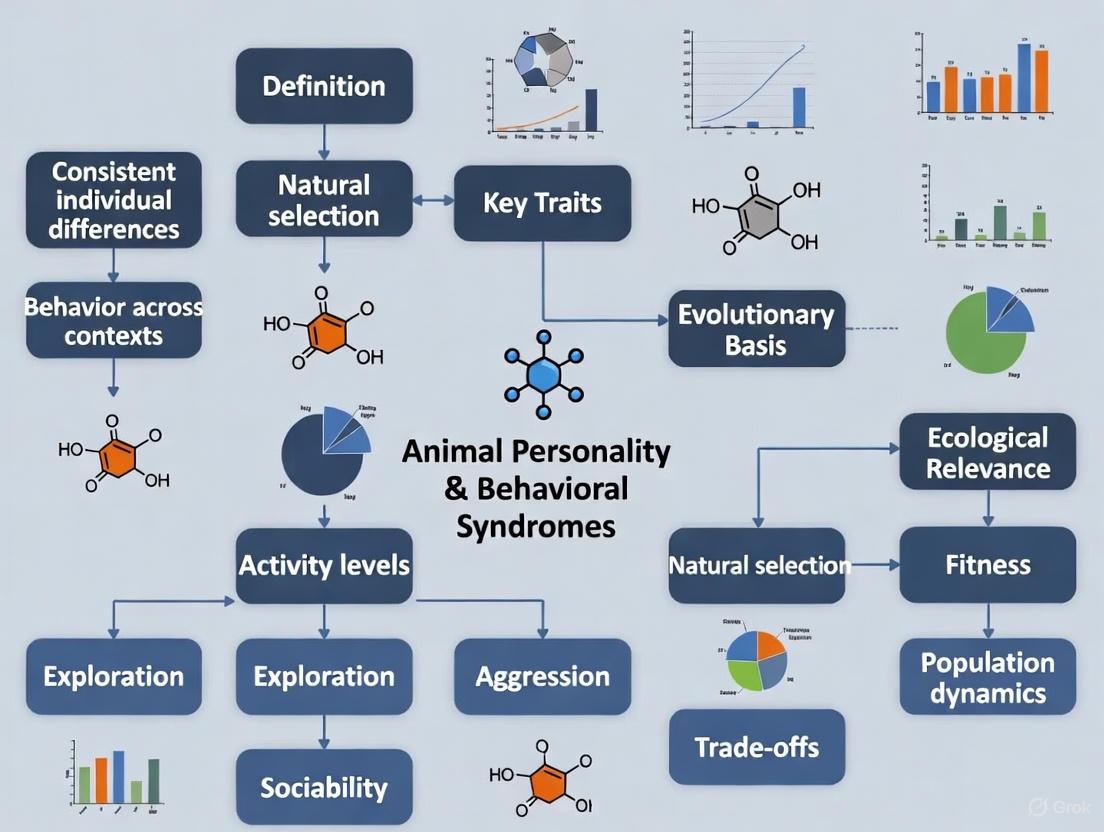

The conceptual relationship between behaviors, personality traits, and behavioral syndromes follows a hierarchical organization, visualized in the following diagram:

This architecture explains why individuals often show limited behavioral plasticity—the same underlying traits manifest across different ecological contexts, necessarily generating suboptimal behavior in some situations [2] [3]. For example, an individual that is aggressive toward conspecifics may also show boldness toward predators and novelty, creating a behavioral type that is successful in some contexts but maladaptive in others. These evolutionary trade-offs maintain variation within populations through frequency-dependent selection, where the fitness of each behavioral type depends on its prevalence in the population [1] [2].

Experimental Evidence and Conservation Applications

Animal personality research has demonstrated significant practical implications, particularly in conservation biology and translocation programs. The selection of individuals based on personality traits directly influences translocation success, with different personality profiles conferring advantages in specific ecological contexts.

Survival Outcomes by Personality Type

Substantial evidence demonstrates how personality traits influence post-release survival in conservation translocations. Boldness carries context-dependent advantages—bolder Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) survived 3.5 times longer after translocation, while shyer swift foxes (Vulpes velox) had higher survival rates [1]. Similarly, more exploratory Blanding's turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) showed enhanced survival, possibly through better resource location [1]. These findings highlight the importance of matching personality types to specific conservation contexts and release environments.

Table 3: Personality-Dependent Survival Outcomes in Translocation Programs

| Species | Personality Trait | Survival Outcome | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swift Fox (Vulpes velox) | Boldness | Bolder individuals died sooner | Increased risk-taking, predator encounters |

| Blanding's Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) | Exploration | More exploratory survived longer | Better resource location (muskrat dens) |

| Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) | Boldness | Bolder survived 3.5x longer | Context-dependent advantage in release environment |

| European Mink (Mustela lutreola) | Boldness, Exploration | Year-dependent effects | Cautious animals favored initially, then bold |

| Blue-fronted Parrot (Amazona aestiva) | Boldness | Shyer survived 40 days longer | Reduced risk-taking in novel environment |

Experimental Protocols for Personality Assessment

Standardized protocols enable consistent measurement of personality traits across species and studies. The novel environment test assesses exploration and activity by introducing individuals into unfamiliar enclosures and recording movement patterns, area covered, and latency to emerge [6]. The predator response assay measures boldness by exposing subjects to predator models or cues and quantifying approach distance, inspection time, and refuge use [1]. Social interaction tests quantify sociability and aggressiveness through controlled conspecific introductions, measuring contact time, aggressive displays, and proximity maintenance [6].

These protocols require careful standardization of testing conditions, including time of day, hunger status, previous experience, and environmental complexity. Multiple testing sessions are essential to establish temporal stability, while varied contexts are necessary to assess contextual consistency. Appropriate acclimation periods minimize novelty stress, and blind testing procedures prevent observer bias in behavioral scoring.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

The experimental investigation of animal personality requires specialized methodological tools and approaches that serve as "research reagents" for standardizing measurements across studies and species.

Table 4: Essential Methodological Tools for Animal Personality Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Behavioral Coding Systems | Quantitative measurement of specific behaviors | Operational definitions of boldness, exploration, aggression |

| Experimental Arenas | Controlled environments for behavioral testing | Open-field tests, novel object setups, maze designs |

| Predator Simulation Apparatus | Standardized threat presentation | Predator models, alarm cue delivery systems |

| Automated Tracking Software | Objective movement and interaction quantification | Video analysis, path tracking, proximity measurement |

| Statistical Repeatability Analysis | Quantifying temporal stability | Mixed models partitioning within/between individual variance |

| Cross-context Test Batteries | Assessing behavioral syndromes | Multiple assays measuring different traits in same individuals |

Future Directions: Expanding the Trait Horizon

While much research has focused on the "Big Five" traits (boldness, exploration, activity, aggressiveness, and sociability), there is growing recognition that this limited framework constrains understanding of animal personality [6]. Many species exhibit consistent individual differences in other ecologically relevant behaviors, including maternal care styles, mating tactics, cognitive biases, and communication patterns [6]. Future research should broaden the trait spectrum to include these understudied dimensions, particularly those most consequential for specific species' ecologies.

The integration of psychological and biological approaches represents another promising frontier [5]. After initial cross-disciplinary fertilization, animal personality research developed largely independently from human personality psychology, with parallel methodological and conceptual advances. Strategic reintegration could leverage complementary strengths, with biology contributing evolutionary theory and field methodologies, and psychology offering sophisticated assessment tools and structural models [5]. This collaboration is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical development, where animal models of personality could predict individual differences in drug responses and treatment efficacy.

Advanced statistical approaches, including multilevel structural equation modeling, Bayesian mixed effects models, and dynamic network analysis, offer powerful new tools for unraveling complex personality structures [5]. These methods can simultaneously capture the hierarchical organization of personality, quantify trait associations, and model personality-development pathways across lifetimes. Combined with genomic, physiological, and neurobiological approaches, these integrated frameworks promise a more comprehensive understanding of animal personality as a biological construct with profound evolutionary significance and practical applications.

Behavioral syndromes represent a foundational concept in behavioral ecology, defined as suites of correlated behaviors exhibited across different contexts or over time [7] [2]. This in-depth technical guide examines the evolutionary origins, ecological consequences, and methodological approaches for studying behavioral syndromes. Also termed "animal personality," this phenomenon reflects consistent between-individual differences in behavior, such as where some individuals are consistently more aggressive, bold, or exploratory than others, even when behavioral plasticity occurs in response to specific situations [7] [8]. Understanding these syndromes provides crucial insights into evolutionary tradeoffs, the maintenance of behavioral variation, and the fundamental connections between animal behavior, ecology, and evolution [7] [2].

The study of behavioral syndromes challenges historical assumptions that animal behavior is infinitely flexible and purely situation-dependent [8]. Research has demonstrated that individuals from the same species or population often maintain consistent behavioral differences, meaning some individuals are consistently more aggressive, more explorative, or shyer than others throughout their lives and across different situations [8]. These behavioral correlations generate important evolutionary tradeoffs; for instance, an aggressive genotype might succeed in competitive situations but fail in contexts requiring caution or parental care [7] [2].

Behavioral syndromes are characterized by two key interrelated aspects: limited behavioral plasticity and behavioral correlations across situations [7]. These constraints appear common in nature, suggesting they may reflect genetic constraints, physiological mechanisms, or stable evolutionary strategies rather than imperfections in the adaptive process [7]. The study of behavioral syndromes integrates proximate and ultimate explanations for animal behavior, examining both the developmental mechanisms and evolutionary consequences of consistent individual differences [8].

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Core Terminology

The field of behavioral syndrome research employs specific terminology that requires precise definition:

- Behavioral Syndrome: A suite of correlated behaviors expressed either within a given behavioral context (e.g., correlations between foraging behaviors in different habitats) or across different contexts (e.g., correlations among feeding, antipredator, mating, aggressive, and dispersal behaviors) [2].

- Behavioral Correlation Across Situations: Between-individual consistency across situations that can either involve the same context in different situations (e.g., feeding activity with versus without predators) or different contexts in different situations (e.g., aggression toward conspecifics versus feeding activity with predators) [7].

- Animal Personality: Consistent individual differences in behavior that remain stable over time and across various situations [8].

- Proactive-Reactive Continuum: A common behavioral syndrome dimension where proactive individuals are typically more aggressive, active, and bold, while reactive individuals are more passive, less active, and shyer [7].

Classifying Behavioral Syndromes

Behavioral syndromes can be categorized based on their breadth and the specific behaviors they connect:

- Domain-Specific Syndromes: Correlations occur within a single behavioral domain, such as within mating behaviors where aggression toward males and females might be correlated [7].

- Broad Cross-Domain Syndromes: Correlations extend across multiple behavioral contexts, potentially linking feeding, mating, contest, antipredator, parental care, and dispersal behaviors [7].

- Contextual Syndromes: The same behaviors may correlate differently across populations or species depending on ecological factors. For example, activity and boldness might correlate positively in high-predation environments but not in low-predation environments [7].

Table 1: Common Types of Behavioral Syndromes and Their Ecological Significance

| Syndrome Type | Behavioral Correlations | Ecological Context | Evolutionary Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression Syndrome | Aggression in mating, competition, and predator inspection contexts [7] | Social and competitive environments | Benefits in competition versus costs of inappropriate aggression [7] [2] |

| Exploration-Avoidance Syndrome | Correlated exploration of novel environments, objects, and food sources [8] | Novel environments and changing habitats | Finding new resources versus predation risk and energy expenditure [7] |

| Activity Syndrome | Feeding activity correlated across different risk levels [7] | Predator-prey interactions | Higher feeding rates versus increased predation risk [7] |

| Boldness-Shyness Continuum | Boldness toward predators, novel objects, and novel food sources [2] | Environments with varying risk and novelty | Acquisition of risky resources versus survival costs [7] |

Evolutionary Framework and Ecological Implications

Evolutionary Origins and Maintenance

Behavioral syndromes persist in populations despite evolutionary pressures that might theoretically decouple maladaptive correlations. Several evolutionary mechanisms explain this maintenance:

- Genetic Constraints: Pleiotropic effects or linkage disequilibrium can genetically couple behaviors, making independent evolution of behavioral traits difficult [7] [8]. For example, genes influencing aggression in one context might have pleiotropic effects on aggression in other contexts [7].

- Stable State-Dependent Strategies: Consistent individual differences can reflect alternative adaptive strategies where different behavioral types achieve similar fitness payoffs under different conditions or states [7].

- Life History Tradeoffs: Behavioral correlations often align with life history strategies, such as correlations between boldness-aggressiveness and high reproductive effort at the cost of survival, versus shyness-unaggressiveness with lower reproductive effort but higher survival [7].

- Fluctuating Selection: Environmental variation across time or space can maintain different behavioral types, with each having fitness advantages under specific conditions [8].

Table 2: Evolutionary Models Explaining Behavioral Syndromes

| Evolutionary Model | Key Mechanism | Predictions | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Constraint | Pleiotropy and genetic linkage create correlations that are difficult to break evolutionarily [7] | Behavioral correlations remain stable across environments; limited behavioral flexibility [7] | Artificial selection studies; cross-fostering experiments demonstrating heritability [8] |

| Adaptive Specialization | Individuals specialize on specific resources or niches, favoring correlated behaviors [7] | Correlation strength varies with ecological factors; fitness tradeoffs across environments [7] | Population comparisons showing different correlation patterns; fitness measurements [7] |

| State-Dependent Feedback | Internal state (size, condition, metabolism) drives consistent behavior [7] | Behavioral consistency linked to individual state; state changes alter behavior | Manipulation of individual condition affects behavioral type [7] |

Ecological Consequences

Behavioral syndromes have profound ecological implications because they can generate tradeoffs that limit species' abilities to cope with environmental factors and couple ecological processes in unexpected ways [7]:

- Species Distributions and Invasiveness: Species with broader behavioral syndromes or greater behavioral flexibility may be more successful invaders, as they can maintain adaptive behavior across novel environments [7]. Inflexible correlations can limit a population's ability to expand into new habitats.

- Population Dynamics: Activity syndromes that link foraging and risk-taking behaviors can directly influence birth and death rates, potentially creating feedback loops that affect population stability [7].

- Trophic Interactions: In predator-prey systems, behavioral syndromes can affect encounter rates and functional responses. For example, correlated activity levels across contexts can create a tradeoff where higher activity increases feeding rates but also increases predation risk [7].

- Speciation Processes: Behavioral correlations can contribute to reproductive isolation if different populations evolve different behavioral correlations, potentially reducing mating success between populations [7].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Measuring and Quantifying Behavioral Syndromes

Research on behavioral syndromes requires standardized protocols for measuring consistent individual differences across contexts and time:

Standardized Behavioral Assays:

- Repeatability Assessment: Measure the same behavioral trait multiple times in the same context to establish baseline consistency (e.g., repeated novel environment tests) [8].

- Cross-Context Testing: Subject individuals to behavioral tests in different contexts (e.g., aggression tests toward conspecifics, predators, and novel objects) [7] [2].

- Temporal Stability Tests: Repeat behavioral assays after significant time intervals (days to weeks) to assess long-term consistency [8].

- Correlational Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients between different behaviors across individuals to identify behavioral syndromes [2].

Experimental Protocol: Aggression Syndrome Characterization

- Objective: Quantify correlations between aggressive behaviors across mating, territorial, and predator inspection contexts.

- Subjects: 40+ individuals from study population to ensure adequate statistical power.

- Procedure:

- Territorial Aggression Test: Record responses to simulated intruder (mirror or conspecific model).

- Mating Context Aggression: Measure aggression toward potential mates versus competitors.

- Predator Inspection: Record boldness and aggressive displays toward predator models.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate between-individual correlations using multivariate statistics; assess repeatability via intraclass correlation coefficients [7] [8].

Advanced Tracking and Visualization Technologies

Recent technological advances enable more precise quantification of animal behavior and head orientation, providing insights into how animals perceive and respond to their environments:

Head Orientation-Determining Systems (HODS):

- Technology: Head-mounted sensors containing tri-axial accelerometers and magnetometers record head movement and directionality [9].

- Data Collection: Sensors typically record at frequencies ≥10 Hz, capturing detailed head movement data across three axes (surge, heave, sway) [9].

- Orientation Sphere (O-Sphere) Visualization: A spherical plot representing head heading as longitude and head pitch as latitude, enabling intuitive visualization of head orientation patterns [9].

- Application: This approach helps identify behaviors and clarify which environmental areas animals prioritize ("environmental framing") by tracking head movements [9].

Head Orientation Tracking Workflow

Analytical Approaches for Social Contexts

Understanding how behavioral syndromes operate in social environments requires specialized analytical techniques:

Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs):

- Application: ERGMs are generative models of social network structure that treat network topology as a response variable, making them ideal for investigating how individual behaviors shape social interactions and group structure [10].

- Utility: These models help answer questions about why specific social associations occur, enabling researchers to test hypotheses about how behavioral types influence social bond formation and maintenance [10].

- Integration with Behavioral Syndromes: ERGMs can determine whether animals with similar behavioral types associate preferentially (assortative mixing) or whether certain behavioral types occupy specific social positions [10].

Behavior-Social Structure Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Behavioral Syndrome Investigations

| Research Tool | Technical Function | Application in Behavioral Syndromes |

|---|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer/Magnetometer | Measures head/body movement and orientation in 3D space [9] | Quantifies activity patterns, head orientation, and movement signatures associated with different behavioral types [9] |

| Orientation Sphere (O-Sphere) Visualization | Spherical plot representing head heading (longitude) and pitch (latitude) [9] | Visualizes environmental framing patterns and identifies characteristic head movement sequences across contexts [9] |

| Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs) | Statistical models for analyzing social network formation and structure [10] | Tests hypotheses about how behavioral types influence social association patterns and network position [10] |

| Standardized Behavioral Assays | Controlled experimental protocols for eliciting specific behaviors [7] [8] | Measures behavioral expression across multiple contexts to identify correlations and consistency [7] |

| Genetic Markers & Quantitative Genetics | Identifies genetic loci associated with behavioral variation [8] | Distinguishes genetic versus environmental contributions to behavioral correlations; identifies pleiotropic effects [7] [8] |

| Hormonal Assay Kits | Measures circulating or excreted hormone levels (corticosterone, testosterone) [8] | Links physiological mechanisms to behavioral type; examines endocrine correlates of syndromes [8] |

| Curcumaromin C | Curcumaromin C, MF:C29H32O4, MW:444.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hemiphroside B | Hemiphroside B, MF:C31H38O17, MW:682.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of consistent individual differences in behavior, often termed animal personality or temperament, has become a central focus in behavioral ecology and comparative psychology. These personality traits represent behavioral tendencies that vary across individuals within a population but remain consistent within individuals across time and contexts [11]. Research conducted over the past two decades has demonstrated that such consistent behavioral differences are not unique to humans but are widespread across the animal kingdom, from invertebrates to mammals [12]. This whitepaper focuses on four core personality dimensions—boldness, exploration, aggression, and sociability—that represent fundamental axes of behavioral variation in animal populations and provide a framework for understanding behavioral syndromes, which are suites of correlated behaviors that occur together across multiple contexts [13] [11].

According to the conceptual framework established by Réale et al. [12] and widely adopted in the field, these dimensions can be defined as follows: boldness represents the propensity to respond to situations that potentially threaten survival; exploration refers to the propensity to be active and collect information in novel situations; aggression describes the propensity to exhibit antagonistic behaviors toward conspecifics; and sociability reflects the propensity to interact with conspecifics [13]. These dimensions are not merely descriptive categories but represent fundamental biological phenomena with physiological underpinnings, evolutionary consequences, and significant implications for understanding individual variation in fitness-related outcomes across species [12] [11].

Table 1: Operational Definitions of Key Personality Dimensions

| Personality Dimension | Operational Definition | Behavioral Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Boldness | Response propensity to situations threatening survival | Latency to emerge from refuge, approach to predator stimuli, risk-taking in open areas |

| Exploration | Propensity to collect information in novel situations | Movement paths in novel environments, investigation of novel objects, information-gathering behaviors |

| Aggression | Propensity for antagonistic behaviors toward conspecifics | Frequency of attacks, threats, chases, or displays toward conspecifics |

| Sociability | Propensity to interact with conspecifics | Time spent near conspecifics, social investigation, affiliative behaviors |

Experimental Paradigms and Assessment Methodologies

Standardized Testing Protocols

Robust assessment of animal personality dimensions requires carefully designed experimental protocols that elicit individual differences while controlling for contextual variables. The behavioral coding approach, which involves measuring the frequency of behaviors from a well-defined ethogram, has emerged as a gold standard in the field [13]. For boldness assessment, novel environment tests combined with predator stimuli presentations have proven highly effective. For instance, in a study of naked mole-rat disperser morphs, researchers employed a Perspex tunnel system with an acclimation pod connected to two other pods (a control pod and a novel object/experimental pod) to quantify boldness responses when exposed to fresh snakeskin as a predator stimulus [13].

Exploration is typically measured through novel environment tests and novel object tests. In the tunnel system used for naked mole-rats, exploration was quantified through behaviors such as scanning (visual inspection while stationary), sniffing (nasal contact with surfaces), and the number of tunnel sections entered during testing periods [13]. Aggression assays often involve resident-intruder paradigms or mirror tests, where subjects are exposed to conspecifics or their own reflection, with aggressive acts (confrontation, biting, shoving) recorded according to standardized ethograms [13]. Sociability measures frequently employ choice tests where subjects can choose to spend time near conspecifics or in isolation, with the proportion of time spent in social proximity serving as the primary metric.

The Behavioral Syndrome Framework

Personality dimensions frequently covary, forming what researchers term behavioral syndromes or coping styles [12]. Individuals with a proactive behavioral syndrome typically exhibit heightened aggressiveness, greater exploration, and increased boldness, along with behavioral inflexibility [13]. By contrast, reactive individuals demonstrate lower aggressiveness, reduced exploration, and diminished boldness, often with greater behavioral flexibility [12]. These syndromes represent integrated suites of behavioral and physiological traits that have important implications for how individuals interact with their environment and conspecifics.

Table 2: Characteristics of Proactive and Reactive Behavioral Syndromes

| Trait Dimension | Proactive Syndrome | Reactive Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Boldness | High | Low |

| Exploration | High | Low |

| Aggression | High | Low |

| Sociability | Variable | Variable |

| Behavioral Flexibility | Low | High |

| Physiological Profile | Elevated sympathetic arousal, dampened HPA reactivity | Lower sympathetic arousal, elevated HPA reactivity |

Quantitative Findings and Data Synthesis

Empirical Evidence Across Taxa

Research across diverse taxa has demonstrated significant repeatability (a measure of consistent individual differences) for the four focal personality dimensions. In a comprehensive study of domestic pigs, researchers tested 101 piglets and demonstrated that behavioral tests for reward sensitivity and approach-avoidance conflicts showed high reproducibility and repeatability, with strong links to established personality dimensions [14]. Similarly, in naked mole-rat disperser morphs, behavioral tests revealed consistent individual differences in boldness and exploration across time and contexts, confirming the presence of distinct personalities in this species [13].

The correlation structure between personality dimensions reveals fascinating evolutionary patterns. For example, boldness and aggression frequently covary across species, as documented in funnel-web spiders, crabs, sticklebacks, and song sparrows [12]. However, these behavioral syndromes are not necessarily consistent across species or environments, suggesting context-dependent evolutionary pressures. For instance, exploration and boldness show positive correlations in some species and environments but not in others, demonstrating the importance of ecological context in shaping personality architecture [12].

Physiological Mechanisms and Biomarkers

A physiological profile approach has advanced our understanding of the mechanistic bases of personality dimensions, moving beyond one-to-one relationships between single behavioral traits and physiological systems to consider integrated multi-system regulation [12]. Research indicates that behavioral variance among individuals is systematically associated with neuroendocrine variance, particularly involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, sympathetic nervous system, and immune function [12].

Proactive individuals typically exhibit elevated sympathetic arousal coupled with dampened HPA axis reactivity, whereas reactive individuals show the opposite pattern with lower sympathetic reactivity and enhanced HPA responses [12]. These physiological differences align with their respective behavioral profiles, with proactive animals showing rapid but inflexible responses and reactive animals demonstrating more measured, flexible behavioral strategies. At the neural level, tendencies to approach rewards and avoid threats involve the behavioral activation system (BAS) and behavioral inhibition system (BIS), which show individual differences in sensitivity and responsivity [14].

Table 3: Physiological Correlates of Personality Dimensions

| Personality Dimension | Physiological Systems | Key Biomarkers/Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Boldness | HPA axis, Sympathetic nervous system | Cortisol/corticosterone levels, heart rate variability, CRH receptor expression |

| Exploration | HPA axis, Mesolimbic dopamine system | Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), dopamine receptor density, novelty-seeking genes |

| Aggression | Sex steroid systems, Serotonin system | Testosterone, estrogen, 5-HIAA levels, androgen receptor expression |

| Sociability | Oxytocin/vasopressin systems, Endogenous opioids | Oxytocin receptor density, vasopressin V1a receptor expression, μ-opioid activation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Research Materials and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Methodologies for Personality Assessment

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Coding Systems | Ethogram development, Behavioral scoring sheets | Standardized measurement of behavioral frequencies and durations |

| Novel Environment Apparatus | Open-field arenas, Perspex tunnel systems, Plus-mazes | Controlled assessment of exploration and boldness in novel settings |

| Social Interaction Tests | Resident-intruder paradigms, Social choice apparatus, Mirror tests | Quantification of aggression and sociability toward conspecifics |

| Stimulus Materials | Predator odors (e.g., fresh snakeskin), Novel objects, Conspecific stimuli | Elicitation of context-specific behavioral responses |

| Data Collection Technology | Video recording systems, Automated tracking software, RFID systems | Objective behavioral recording and analysis |

| Physiological Assays | Salivary cortisol kits, Heart rate monitors, Immune factor assays | Correlation of behavioral traits with physiological parameters |

| Gelsempervine A | Gelsempervine A, MF:C22H26N2O4, MW:382.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pungiolide A | Pungiolide A, MF:C30H36O7, MW:508.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Evolutionary Context and Life-History Connections

Personality dimensions have profound implications for evolutionary fitness through their connections to life-history strategies. Research has demonstrated that behavioral traits like boldness, exploration, and aggression directly affect fitness components including survival, reproductive success, and dispersal [12] [11]. These personality traits are linked to life-history productivity, defined as the generation of new biomass through growth or reproduction [11]. Empirical studies across diverse taxa have revealed positive correlations between personality traits and productivity metrics, supporting the hypothesis that consistent individual differences in personality are maintained by life-history tradeoffs [11].

The evolutionary maintenance of personality variation can be understood through tradeoffs between growth and mortality or between fecundity and mortality [11]. For instance, bolder, more aggressive individuals may achieve higher food intake rates and greater reproductive success in the short term but suffer increased predation risk or physiological costs that reduce longevity [11]. This evolutionary framework explains why multiple behavioral types can persist within populations—different strategies prove advantageous under varying environmental conditions or at different points in life-history trajectories.

Future Research Directions and Integrative Approaches

The field of animal personality research is currently experiencing a paradigmatic shift toward increased integration across biological and psychological perspectives [5]. Future research directions include developing more standardized designs and assessment tools to capture defined behavioral dimensions, analyzing the magnitude and dimensionality of behavioral differences within and between individuals and species, and investigating the robustness of specific genetic, environmental, and gene × environment interaction effects [5]. There is also growing recognition of the need to understand the development and stability of personality across the lifespan and the consequences of personality for social, health, and performance domains [5].

A call for papers from Personality Science highlights the urgent need for integrative approaches that bridge personality psychology and animal personality research, leveraging complementary conceptual and methodological strengths across these fields [5]. Such integration will help illuminate the species-generality versus species-specificity of personality dimensions and open new perspectives for defining what, if anything, is uniquely human about personality organization [5]. This interdisciplinary approach will be essential for advancing our understanding of the four key personality dimensions—boldness, exploration, aggression, and sociability—and their role in shaping individual differences in behavior across the animal kingdom.

In classical evolutionary theory, one might expect natural selection to inevitably drive populations toward a single, optimal behavioral phenotype. The persistent and systematic variation in animal behavior—where some individuals are consistently more aggressive, exploratory, or social than others—presents a compelling scientific puzzle. This phenomenon, termed animal personality or behavioral syndromes, refers to consistent individual differences in behavior that are stable across time and contexts [8]. The concept of the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) provides the fundamental theoretical resolution to this puzzle, demonstrating how and why such variation can be maintained by natural selection rather than eroded by it. An ESS is a strategy that, once adopted by a population, cannot be invaded by any alternative strategy through natural selection [15] [16] [17]. This framework reveals that behavioral variation is not merely evolutionary "noise" but can represent a stable evolutionary endpoint arising from frequency-dependent selection, where the fitness of a behavioral strategy depends on the strategies employed by others in the population [17] [18].

Theoretical Foundations of the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy

Core Definition and Historical Development

The ESS concept was formally introduced by John Maynard Smith and George R. Price in 1973 to explain the evolution of ritualized animal conflict, specifically why animals often engage in relatively harmless displays rather than deadly combat [19] [18]. Their seminal work demonstrated that game theory, originally developed for human economic behavior, could be powerfully applied to evolutionary biology by treating strategies as phenotypes and payoffs as contributions to fitness [17] [18]. This approach differed fundamentally from earlier applications of game theory to evolution that viewed populations as playing against "nature," instead focusing on strategic interactions between individuals within populations [18].

An ESS must satisfy one of two mathematical conditions against any potential mutant strategy y attempting to invade a resident population employing strategy xâ [16] [17] [20]:

- E(x, x) > E(y, x), or

- If E(x, x) = E(y, x), then E(x, y) > E(y, y)

where E(a, b) represents the payoff (fitness) to strategy a when interacting with strategy b. The first condition ensures that the resident strategy performs better against itself than any mutant does against the resident. The second condition provides additional stability for cases where this initial requirement is met equally, stating that the resident must outperform the mutant in interactions with the mutant itself [17].

The Hawk-Dove Game: A Paradigm for Behavioral Evolution

The Hawk-Dove game stands as the classic illustration of ESS analysis, modeling the evolution of aggression versus pacifism in animal contests [15] [19] [17]. The game involves two strategies competing for a resource of value V with potential injury cost C:

- Hawk: Always escalate fights until injured or until the opponent retreats

- Dove: Display but retreat immediately if the opponent escalates

Table 1: Payoff Matrix for the Hawk-Dove Game

| Focal Player Strategy | Opponent: Hawk | Opponent: Dove |

|---|---|---|

| Hawk | (V-C)/2 | V |

| Dove | 0 | V/2 |

The ESS solution depends critically on the relationship between resource value and conflict cost:

- When V > C, the Hawk strategy is a pure ESS because it provides higher payoffs regardless of opponent strategy [15]

- When V < C (the biologically common scenario), neither pure strategy is stable alone. Instead, a mixed ESS emerges at a frequency of V/C Hawks and 1 - V/C Doves [19] [17]

This mixed ESS represents a stable polymorphism where both behavioral types coexist indefinitely, providing a fundamental explanation for why populations maintain both aggressive and non-aggressive behavioral phenotypes [15] [17]. The diagram below illustrates the logical structure and outcomes of the Hawk-Dove game.

Integrating ESS Theory with Animal Personality Research

From Strategic Polymorphisms to Behavioral Syndromes

ESS theory provides the evolutionary rationale for maintaining behavioral variation, while animal personality research documents the empirical manifestations of this variation [8]. The mixed ESS in the Hawk-Dove game directly corresponds to what behavioral ecologists observe as the "boldness-shyness" continuum in natural populations, where individuals consistently differ in risk-taking propensity across situations and throughout their lifetimes [8]. These consistent behavioral differences often form behavioral syndromes—correlated suites of behaviors across multiple contexts—that represent alternative evolutionary strategies maintained by frequency-dependent selection [8].

Recent research has established strong connections between these behavioral tendencies and underlying neurobiological systems. The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory proposes three core motivational systems regulating approach-avoidance behaviors [21]:

- Behavioral Activation System (BAS): Reward-driven approach behavior

- Fight-Flight-Freeze System (FFFS): Fear-driven avoidance behavior

- Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS): Mediates approach-avoidance conflicts

In domestic pigs, high BAS responsiveness correlates with exploratory and social behaviors, while high BIS activity correlates with behavioral inhibition in novel situations, demonstrating how fundamental motivational systems underlie personality variation and may be maintained as alternative evolutionary strategies [21].

Empirical Evidence for ESS in Behavioral Variation

Multiple lines of evidence support ESS mechanisms in maintaining animal personalities:

- Fitness consequences: Different behavioral types show equal lifetime reproductive success in stable environments, satisfying the ESS condition of equal fitness at equilibrium [8]

- Frequency-dependent selection: The fitness advantage of particular behavioral strategies changes with their frequency in the population [15] [17]

- Genetic heritability: Behavioral traits show significant heritability, confirming they are subject to evolutionary processes [8]

- Developmental stability: Individual behavioral differences persist throughout an animal's lifetime and across contexts [8]

Table 2: Evolutionary Mechanisms Maintaining Behavioral Variation

| Mechanism | ESS Basis | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency-Dependent Selection | Fitness depends on strategy frequency in population | Hawk-Dove game polymorphisms; rock-paper-scissors dynamics in side-blotched lizards |

| State-Dependent Strategies | Individual condition affects optimal strategy | Size-dependent aggression; resource-holding potential variations |

| Spatial/Temporal Heterogeneity | Environmental variation favors different strategies | Habitat-specific optimal activity levels; seasonal food availability effects |

| Genetic Constraints | Pleiotropic effects maintain correlated behaviors | Behavioral syndromes; genetic correlations between boldness and aggression |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for ESS Research

Standardized Behavioral Assays for Personality Assessment

Research on animal personality and ESS employs standardized behavioral tests to quantify consistent individual differences. The following protocols represent established methodologies in the field [21] [8]:

Open-Field Test (OFT)

- Purpose: Measures exploration, boldness, and general activity in a novel environment

- Protocol: Place individual in a novel, empty arena for standardized duration (typically 10-15 minutes)

- Measurements: Latency to enter, distance traveled, time spent in center versus periphery, freezing behavior

- Validation: Shows high repeatability and heritability in multiple species

Novel Object Test (NOT)

- Purpose: Assesses neophobia and curiosity toward unfamiliar stimuli

- Protocol: Introduce a novel object into the arena after habituation period

- Measurements: Latency to approach, time spent investigating, number of contacts

- Personality Dimensions: Boldness, exploration, neophobia

Human Approach Test (HAT)

- Purpose: Quantifies reactions to potential predators/humans

- Protocol: Experimenter enters arena or approaches test subject systematically

- Measurements: Minimum approach distance, flight initiation distance, investigative behavior

- Applications: Widely used in conservation and wildlife management

Novel Peer Test (NPT)

- Purpose: Measures sociability and reaction to unfamiliar conspecifics

- Protocol: Introduce unfamiliar individual (or model) into testing arena

- Measurements: Social investigation, aggressive displays, proximity maintenance

- Validation: Correlates with BAS sensitivity in pigs [21]

The BIBAGO Test: Quantifying Approach-Avoidance Conflicts

A recently developed methodology specifically targets the neurobiological systems underlying personality variation. The BIBAGO test (BIS/BAS, Goursot) simultaneously presents positive (treat ball) and negative (moving plastic bag) stimuli to activate BAS, FFFS, and BIS systems separately [21]. This protocol provides:

- BAS Measurement: Interactions with reward, chewing sounds, number of rewards eaten

- FFFS Measurement: Freezing behavior, retreat to safe areas

- BIS Measurement: Interruption of vocalizations, approach-avoidance conflict behaviors

The BIBAGO demonstrates high repeatability and correlates with established personality dimensions, offering a direct experimental bridge between evolutionary game theory and neurobehavioral mechanisms maintaining behavioral variation [21].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ESS and Animal Personality Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Tracking Systems | Quantify movement patterns, activity budgets, and social interactions | EthoVision, ANY-maze, BioObserver for OFT and NOT |

| Behavioral Coding Software | Systematic analysis of video-recorded behavioral sequences | BORIS, Observer XT for structured ethograms |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Identify heritability and genetic architecture of behavioral traits | SNP arrays, RAD sequencing, pedigree analysis |

| Hormonal Assay Kits | Measure corticosteroid and androgen levels as physiological correlates | CORT ELISA, testosterone RIA for stress and aggression |

| Neurobiological Markers | Localize neural activity in BAS/FFFS/BIS circuits | c-Fos immunohistochemistry, immediate early gene expression |

| Game Theory Modeling Software | Simulate evolutionary dynamics and ESS conditions | MATLAB, R with games and deSolve packages |

Advanced Concepts: Expanding the ESS Framework

The Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma and Cooperation

Beyond the Hawk-Dove game, the Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma provides crucial insights into how cooperative behaviors can persist as evolutionary stable strategies. While single encounters favor defection, repeated interactions enable reciprocal altruism to evolve [15]. The "tit for tat" strategy—begin with cooperation, then mirror the opponent's previous move—emerges as a robust ESS when the probability of future encounters is sufficiently high [15]. This evolutionary framework explains the persistence of cooperative and altruistic behaviors that initially appear contradictory to "survival of the fittest" [15].

Complex Evolutionary Games and Behavioral Diversity

Natural systems often involve more complex strategic interactions than simple two-strategy games [15] [19]:

- War of Attrition: Models contests where persistence time determines success, leading to mixed ESS with random persistence times

- Bourgeois Strategy: Uses asymmetries (like prior ownership) to resolve conflicts without fighting

- Rock-Paper-Scissors Dynamics: Creates cyclic frequency-dependent selection, as observed in Escherichia coli colicin polymorphisms and side-blotched lizard mating strategies [22]

These complex games demonstrate how multiple behavioral strategies can coexist indefinitely through negative frequency-dependent selection, providing a comprehensive evolutionary explanation for the remarkable behavioral diversity observed in natural populations [15] [22].

The concept of the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy provides a powerful mathematical foundation for understanding why behavioral variation persists in natural populations. By demonstrating how frequency-dependent selection can maintain multiple behavioral phenotypes indefinitely, ESS theory resolves the apparent paradox of consistent individual differences in behavior. The integration of ESS models with empirical research on animal personalities has created a robust framework that connects evolutionary dynamics, neurobiological mechanisms, and ecological consequences.

Future research directions include:

- Linking specific genetic polymorphisms to ESS-maintained behavioral strategies

- Exploring how environmental change shifts ESS equilibria and behavioral distributions

- Integrating ESS theory with complex neurogenetic architectures underlying behavior

- Applying ESS concepts to conservation challenges involving behavioral diversity

This evolutionary perspective reveals that behavioral variation is not transitional but represents stable evolutionary endpoints, with profound implications for understanding individual differences, species interactions, and biodiversity conservation in changing environments.

In evolutionary biology, the fitness landscape is a powerful metaphor for visualizing the relationship between genotypes, phenotypes, and reproductive success [23]. This model, first introduced by Sewall Wright in 1932, conceptualizes fitness as height, with genotypes that are similar being "close" to one another in the landscape [23]. Populations evolving under natural selection typically climb uphill in this landscape through a series of small genetic changes until they reach a local optimum [23].

The concept of animal personality—consistent individual differences in behavior across time and contexts—adds a crucial layer of complexity to this evolutionary framework [8]. When individuals within a species or population consistently differ in their behavior (e.g., some are consistently more aggressive, explorative, or shy than others), this phenomenon, also termed a behavioural syndrome, must be subject to evolutionary processes, as it has been shown to be heritable and to entail fitness consequences [8].

This article explores the intersection of these two concepts, examining how the adaptive value of specific personality traits is not absolute but is profoundly shaped by the multifaceted environmental, social, and temporal context—the fitness landscape itself.

Theoretical Framework: Fitness Landscapes and Seascapes

Types of Fitness Landscapes

Fitness landscapes can be characterized in three primary ways, differentiated by what the dimensions of the landscape represent [23]:

- Genotype to Fitness Landscapes: Wright visualized genotype space as a hypercube, where a network of genotypes are connected via mutational paths without continuous genotype dimensions [23]. Stuart Kauffman's NK model falls into this category [23].

- Allele Frequency to Fitness Landscapes: In Wright's mathematical work, each dimension describes an allele frequency at a different gene, ranging from 0 to 1 [23].

- Phenotype to Fitness Landscapes: Here, each dimension represents a different phenotypic trait, which under the assumptions of quantitative genetics, can be mapped onto genotypes [23].

From Static Landscapes to Dynamic Seascapes

A critical extension of the classic fitness landscape model is the fitness seascape, which allows the adaptive topography to shift through time or across changing environments [23]. Rather than a fixed topography, seascapes describe adaptive surfaces whose peaks and valleys change dynamically, which is necessary to accurately predict adaptation under time-varying selective conditions [23].

Factors that cause time-varying fitness landscapes/seascapes include [23]:

- Environmental change

- Drug exposure and cycling

- Immune surveillance

- Evolving host environments

- Red Queen effects, where interactions between two species dynamically affect each one's fitness landscape

Table: Key Characteristics of Fitness Landscapes vs. Seascapes

| Characteristic | Fitness Landscape | Fitness Seascape |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Dynamics | Static | Dynamic, time-varying |

| Adaptive Peaks | Stable position | Shifting position |

| Selection Pressures | Constant | Fluctuating |

| Evolutionary Trajectories | Predictable toward stable optima | More complex, may track moving peaks |

| Primary Model Use | Understanding basic evolutionary principles | Modeling real-world, changing environments |

Animal Personality in Evolutionary Context

Defining Animal Personality and Behavioral Syndromes

Behaviors are considered among the most flexible traits in animals, yet individuals within the same species or populations often consistently differ in their behavior—some individuals are consistently more aggressive, more explorative, or shyer than others [8]. This phenomenon of consistent individual behavioral differences has been termed 'animal personality' or a 'behavioural syndrome' [8].

Research has demonstrated that animal personality is heritable and entails fitness consequences, demonstrating that it is subject to evolutionary processes [8]. Furthermore, as consistent individual differences in behavior can result from developmental processes, research on animal personality integrates proximate and functional questions about animal behavior [8].

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Animal Personality

The existence of animal personality presents three fundamental evolutionary questions [8]:

- Why are individuals consistent in their behavior?

- Why do individual differences in behavior exist?

- Why are behavioral traits sometimes correlated with each other?

Several evolutionary concepts have been proposed to explain these phenomena, including life-history trade-offs, frequency-dependent selection, and spatial/temporal variation in selection pressures [8].

Context-Dependent Selection on Personality Traits

Ecological Contexts

The adaptive value of personality traits varies dramatically across different ecological contexts. A trait that enhances fitness in one environmental setting may reduce it in another.

Table: Fitness Outcomes of Personality Traits Across Ecological Contexts

| Personality Trait | High-Fitness Context | Low-Fitness Context | Empirical Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Aggression | High resource competition, stable territories | High predation risk, social species | Sticklebacks under predation pressure [8] |

| Boldness/Exploration | Novel environments, low predation | High predation, familiar environments | Great tits in fluctuating environments [8] |

| Sociability | Cooperative breeding, group defense | Solitary species, resource scarcity | Cooperative cichlid fish [8] |

| Neophobia | Stable, familiar environments | Changing environments, new resources | Multiple bird and fish species [8] |

Social and Frequency-Dependent Selection

The fitness landscape for personality traits is also shaped by social context and the distribution of traits within a population. Frequency-dependent selection occurs when the fitness of a behavioral phenotype depends on its frequency relative to other phenotypes in the population.

- In three-spined sticklebacks, Bell and Sih demonstrated that exposure to predation generates personality,

- Research on great tits has shown that pairs of extreme avian personalities have highest reproductive success [8],

- Theoretical models suggest that consistent individual differences can result from strategic niche specialization [8].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Quantifying Animal Personality

Standardized protocols for measuring animal personality typically involve:

- Repeated Behavioral Assays: Individuals are tested multiple times in standardized contexts to measure consistency.

- Multiple Context Testing: The same individuals are observed across different situations (e.g., novel environment, predator exposure, social interaction).

- Statistical Analysis of Repeatability: Calculation of behavioral repeatability using intraclass correlation coefficients.

Measuring Fitness Consequences

Research protocols for linking personality to fitness include:

- Longitudinal Studies: Tracking individuals throughout their lifetimes to measure reproductive success and survival.

- Experimental Manipulations: Altering environmental conditions to measure how fitness landscapes shift.

- Cross-Population Comparisons: Comparing selection gradients across different populations occupying different ecological contexts.

Table: Essential Research Tools for Animal Personality Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Tracking | Automated video tracking systems, RFID technology, GPS loggers | Quantify movement, exploration, and social interactions |

| Physiological Measures | Cortticosterone/cortisol assays, heart rate monitors, metabolic chambers | Measure stress response, energy expenditure |

| Genetic Analysis | SNP genotyping, pedigree analysis, gene expression profiling | Determine heritability, identify genetic correlates |

| Environmental Monitoring | Temperature loggers, food availability measures, predator density counts | Characterize environmental context |

| Statistical Tools | Mixed-effects models, structural equation modeling, multivariate analysis | Analyze behavioral consistency and fitness consequences |

Experimental Evolution Approaches

Advanced methodologies include:

- Artificial Selection Lines: Selectively breeding for specific personality traits to study evolutionary responses.

- Transplant Experiments: Introducing individuals with known personalities into new environments to measure fitness consequences.

- Resource Manipulation: Experimentally altering resource availability to study how this shifts the fitness landscape.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Animal Personality Research

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Behavioral Arenas | Standardized testing environments with controlled stimuli | Novel environment tests, open field assays |

| Biotelemetry Systems | Remote monitoring of physiology and movement | Heart rate monitoring during stressful events |

| Hormone Assay Kits (CORT, Testosterone) | Quantifying endocrine correlates of personality | Stress response profiling |

| Genetic Sequencing Kits | Genotyping and expression analysis | Identifying genetic bases of behavioral syndromes |

| Predator Stimuli | Standardized predator models or odors | Measuring anti-predator responses and boldness |

| Video Tracking Software (e.g., EthoVision) | Automated behavior quantification | Analysis of movement patterns and social interactions |

Conceptual Diagram: Personality in a Dynamic Fitness Seascape

Diagram 1: Contextual Influences on Personality Fitness. This model illustrates how multiple contextual factors shape the expression and fitness consequences of personality traits within a dynamic fitness seascape, creating feedback loops that drive evolutionary change.

The fitness landscape framework provides powerful conceptual tools for understanding how context shapes the value of personality traits. Rather than being fixed attributes with constant fitness values, personality traits exist within dynamic fitness seascapes where their adaptive significance shifts with ecological, social, and temporal variables. This perspective helps explain the maintenance of individual differences in behavior within populations and highlights the importance of environmental heterogeneity in shaping evolutionary trajectories.

Future research in animal personality should increasingly incorporate the dynamic nature of fitness seascapes, particularly in the context of rapid environmental change caused by human activities. Understanding how fitness landscapes are shifting will be crucial for predicting evolutionary responses and for conservation efforts aimed at preserving behavioral diversity in natural populations.

Measuring the Unseen: Innovative Methods and Translational Applications of Personality Assessment

The study of animal personality and behavioral syndromes requires robust, reproducible, and standardized methodological approaches. Behavioral assays provide the foundational tools for quantifying consistent individual differences in behavior across time and contexts, enabling researchers to explore the neural, genetic, and environmental underpinnings of personality [21]. In both human and non-human animal research, personality describes these consistent individual differences, with traits such as exploration, boldness, and sociability providing a framework for understanding individual variation in coping strategies, stress responses, and vulnerability to psychopathology [21].

The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality offers a neurobiological framework for understanding these individual differences, proposing three core motivational systems: the behavioral activation system (BAS) governing reward-driven approach; the fight-flight-freeze system (FFFS) mediating fear-driven avoidance; and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) resolving approach-avoidance conflicts [21]. Standardized behavioral assays, including the open field test and novel object reactions, operationalize these constructs by presenting animals with standardized environmental challenges, allowing researchers to quantify behaviors along these fundamental dimensions. This article provides a comprehensive technical guide to the primary behavioral assays used in animal personality research, with detailed methodologies, data interpretation frameworks, and integration strategies for comprehensive behavioral phenotyping.

Core Behavioral Paradigms: Methodologies and Applications

Open Field Test (OFT)

The Open Field Test is a widely used assessment that evaluates locomotor activity, anxiety-like behavior, and general exploratory tendencies in a novel environment [24] [21].

Basic Protocol [24]:

- Equipment: A square, open arena (size appropriate to species), controlled lighting (typically 50-100 lux in center), video camera with tracking software (e.g., EthoVision XT, Any-maze), sound-attenuating room, cleaning supplies (70% ethanol).

- Procedure: The animal is placed in the center (or near the wall, depending on the specific protocol) of the empty arena and allowed to explore freely for a predetermined session (typically 10-30 minutes). The session is recorded for subsequent automated or manual analysis.

- Key Measurements:

- Activity Level: Total distance traveled, average velocity, rearing frequency.

- Anxiety-like Behavior: Time spent in the center zone vs. periphery, number of entries to the center zone, latency to enter center.

- Exploratory Behavior: Qualitative analysis of specific exploratory acts (e.g., sniffing, rearing against the wall) [25].

- Special Considerations for Lupus Models: Mouse models of neuropsychiatric disease such as NPSLE may exhibit heightened stress sensitivity, motor impairments, or light sensitivity. Proper habituation to handling and test room, consistent timing of tests, and consideration of test order in a battery are crucial to minimize confounding effects [24].

Novel Object Recognition (NOR) and Novel Object Tests

These tests assess learning, memory, and exploratory behavior (neophilia/neophobia) by leveraging the natural tendency of rodents to investigate a novel object over a familiar one [24].

Basic Protocol [24]:

- Equipment: The same open field arena, two identical objects in the familiarization phase, one familiar and one novel object in the test phase. Objects should be of similar size but different shapes, made of non-porous, easy-to-clean materials.

- Procedure:

- Habituation: The animal is allowed to explore the empty arena.

- Familiarization: Two identical objects (A1 and A2) are placed in the arena, and the animal is given a session to explore them.

- Retention Delay: The animal is removed from the arena for a delay period (short-term: minutes-hours; long-term: 24 hours).

- Test Session: One familiar object (A) is replaced with a novel object (B). The animal is returned to the arena, and exploration of both objects is recorded.

- Key Measurements: Discrimination index [(Time with Novel - Time with Familiar) / Total exploration time], total exploration time, and recognition index (Time with Novel / Total exploration time). Automated analysis using machine learning and image processing is increasingly used for high-throughput and objective scoring [26].

- Interpretation: A significant preference for the novel object indicates successful encoding and retention of the familiar object, reflecting intact recognition memory.

Anxiety and Conflict-Based Assays

These tests measure anxiety-related behavior by creating a conflict between the innate exploratory drive and the aversion to potentially dangerous areas.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) [24]:

- Equipment: A plus-shaped maze elevated from the floor with two open arms (without walls) and two enclosed arms (with high walls).

- Procedure: The animal is placed in the central square facing an open arm and allowed to explore for 5-10 minutes.

- Key Measurements: Percentage of time spent in open arms, number of open arm entries, total arm entries (as a measure of general activity).

Dark-Light Box (DLB) [24]:

- Equipment: A two-chambered box, one dark and enclosed, the other brightly lit and open, connected by a small opening.

- Procedure: The animal is placed in the light compartment, and its behavior is recorded for 5-10 minutes.

- Key Measurements: Latency to enter the dark compartment, time spent in the light compartment, number of transitions between compartments.

BIBAGO Test [21]: This newer test is specifically designed to measure the BIS/BAS motivational systems by presenting simultaneous positive (e.g., a treat ball) and negative (e.g., a moving plastic bag) stimuli.

- Key Measurements: BAS-related: Interactions with the reward, number of rewards eaten. BIS/FFFS-related: Freezing behavior, interruption of vocalizations upon stimulus presentation, time spent in conflict zones.

Tests for Depression-like Behavior

These tests measure behavioral despair or passive coping strategies in inescapable stress situations.

Tail Suspension Test (TST) [24]:

- Procedure: A mouse is suspended by its tail for 6 minutes using adhesive tape.

- Key Measurements: Total immobility time, latency to first immobility.

Porsolt Swim Test (Forced Swim Test) [24]:

- Procedure: A rodent is placed in a water-filled cylinder from which it cannot escape for 6 minutes.

- Key Measurements: Total immobility time (time when the animal makes only movements necessary to keep its head above water), latency to immobility.

Spatial Learning and Memory

Barnes Maze [24]:

- Equipment: A circular platform with multiple holes around its perimeter, one of which leads to an escape box.

- Procedure: The animal is motivated to find the escape box using distal spatial cues over several training days, followed by a probe trial with the escape box removed.

- Key Measurements: Latency to find the target hole, number of errors (investigating incorrect holes), path efficiency, and search strategy during the probe trial.

Table 1: Key Behavioral Domains and Corresponding Assays

| Behavioral Domain | Primary Assays | Core Measured Parameters | Linked Motivational System/Personality Trait |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Activity & Exploration | Open Field Test [24] [25] | Distance traveled, Rearing, Arena exploration [21] | Activity, Proactivity, Exploration/Boldness [21] |

| Anxiety-like Behavior | Open Field Test, Elevated Plus Maze, Dark-Light Box [24] | Time in center/open arms/light side, Latency to transition | Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) [21], Neuroticism |

| Approach-Avoidance Conflict | BIBAGO Test [21] | Freezing, Reward interaction during conflict, Interruption of vocalizations | Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) [21] |

| Reward Sensitivity | BIBAGO Test [21] | Rewards eaten, Interactions with reward, Tail wagging | Behavioral Activation System (BAS) [21], Extraversion |

| Cognitive Function & Memory | Novel Object Recognition, Barnes Maze [24] | Discrimination Index, Latency to target, Errors | Executive function, Spatial learning |

| Depression-like Behavior | Tail Suspension Test, Porsolt Swim Test [24] | Immobility time, Latency to immobility | Passive coping, Behavioral despair |

| Sociability | Novel Peer Test [21] | Time interacting with conspecific, Proximity | Sociability (resembles human Extraversion) [21] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful behavioral phenotyping requires careful selection and standardization of materials. The following table details key components of a behavioral neuroscience laboratory.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Behavioral Phenotyping

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Arena(s) | Provides the controlled environment for tests like OFT, NOR. | Square or circular; size-species appropriate (e.g., 40x40cm for mice); constructed of non-porous, easy-to-clean material (white plastic, methacrylate); possible integration with ceiling-mounted cameras. |

| Video Tracking System | Automated, high-fidelity recording and analysis of animal movement and position. | Includes camera (high-resolution, low-light capable) and software (e.g., EthoVision XT, Any-maze); critical for measuring path, velocity, time in zone. |