Behavioral Ecology vs Evolutionary Psychology: A Comparative Framework for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Behavioral Ecology and Evolutionary Psychology, two dominant frameworks for understanding the evolution of human behavior.

Behavioral Ecology vs Evolutionary Psychology: A Comparative Framework for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Behavioral Ecology and Evolutionary Psychology, two dominant frameworks for understanding the evolution of human behavior. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological approaches, and key debates distinguishing these fields. The content covers their unique perspectives on behavioral adaptation, modularity, and the role of culture, addressing common criticisms and replication challenges. A central focus is placed on the practical implications for biomedical research, including interpreting behavioral phenotypes, understanding maladaptation, and developing evolutionary-informed models for clinical and pharmacological applications.

Core Principles and Historical Divergence: Laying the Groundwork

Within the evolutionary behavioral sciences, two prominent frameworks—behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology—provide distinct, yet sometimes complementary, approaches to understanding human behavior. Both are grounded in Darwinian principles but diverge in their core aims, central questions, and methodological preferences. Behavioral ecology often emphasizes current adaptive function and behavioral flexibility in response to ecological conditions, while evolutionary psychology typically seeks to identify the universal, evolved psychological mechanisms that generated behavior in our ancestral past. This guide provides a objective comparison of these frameworks for researchers, detailing their theoretical underpinnings and the experimental approaches used to test their hypotheses.

Theoretical Foundations at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core theoretical distinctions between human behavioral ecology (HBE) and evolutionary psychology (EP).

Table 1: Core Theoretical Distinctions Between Frameworks

| Aspect | Human Behavioral Ecology (HBE) | Evolutionary Psychology (EP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | How ecological and social contexts shape behavioral strategies to maximize fitness [1]. | Identifying universal, evolved psychological mechanisms that underlie behavior [2]. |

| View of Mind | Emphasizes domain-general learning mechanisms and phenotypic plasticity [1]. | Proposes a massive modularity of mind, with many domain-specific programs [2]. |

| Key Question | What is the current function and adaptive value of a behavior in a specific environment? [1] | What psychological adaptations were selected for in our evolutionary history? [2] |

| View on Diversity | Behavioral diversity is a central focus, explained as adaptive responses to varying environments [1]. | Underlying psychological mechanisms are universal; surface-level diversity is the output of universal mechanisms in different contexts [2] [1]. |

| Time Frame | Focuses on current selective pressures and contemporary adaptation [1]. | Focuses on the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA), usually the Pleistocene [2]. |

| Inheritance System | Focuses on genetic inheritance and adaptive phenotypic plasticity [1]. | Focuses heavily on genetic inheritance of psychological traits, with culture as an output [2] [1]. |

Experimental Paradigms and Key Findings

The following experiments illustrate the characteristic methodologies and data types employed by each framework.

A Behavioral Ecology Experiment: Spatial Memory for Forageable Plants

This 2025 study investigates how the evolutionary salience of various plant attributes influences spatial memory, a key skill for foraging [3].

- Aim: To test if human spatial memory shows an adaptive bias towards remembering the location of plants with attributes that would have enhanced ancestral survival.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Participants: 60 Iranian individuals participating online.

- Stimuli: Arrays of fruit and vegetable images, categorized by attributes like calorie density, ripeness, size, perishability, and availability during scarcity.

- Task: Participants viewed the arrays and were later asked to recall the locations of the items.

- Data Analysis: Recall accuracy was compared across the different attribute categories to identify which traits were associated with enhanced spatial memory.

- Key Quantitative Findings:

Table 2: Key Findings from the Spatial Memory Study [3]

| Plant Attribute | Experimental Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Calorie Density | Enhanced recall for higher-calorie fruits and vegetables. | Supports adaptive memory bias for nutritionally dense resources. |

| Ripeness | No significant differences in recall for ripe vs. unripe products. | Does not support a mnemonic bias for this specific cue. |

| Size | No significant differences in recall for larger vs. smaller items. | Does not support a mnemonic bias for this specific cue. |

| Sex Differences | Women showed no significant differences in spatial memory. | Suggests the adaptive bias is not sex-specific in this context. |

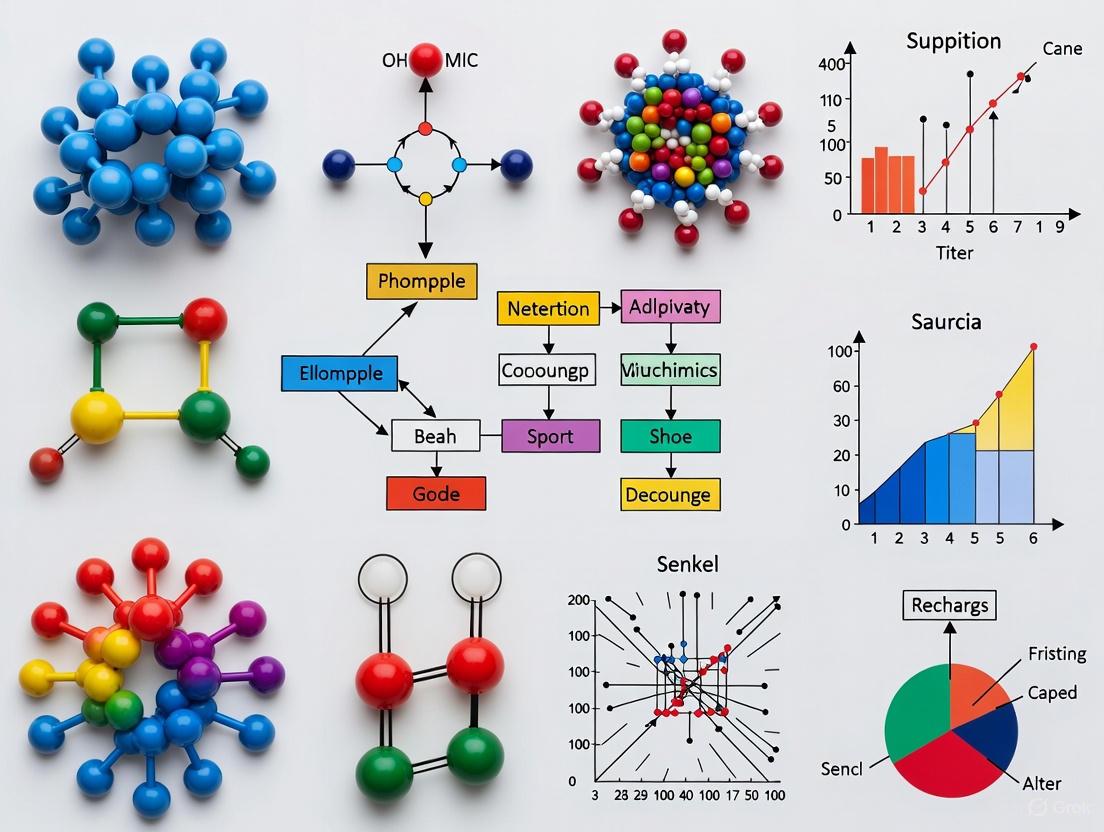

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the adaptive decision-making process under investigation in this behavioral ecology approach.

An Evolutionary Psychology Experiment: Bullying and Romantic Involvement

This 2025 study tests an evolutionary hypothesis that bullying peers can be an adaptive strategy associated with enhanced romantic success, particularly for adolescents with low social status [3].

- Aim: To examine if bullying same-sex and opposite-sex peers is longitudinally predictive of romantic involvement, and if popularity moderates this relationship.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Design: A longitudinal study of Indonesian adolescents, initially assessed in 10th grade and reassessed two years later.

- Measures:

- Bullying: Measured via classroom peer nominations, distinguishing between bullying of same-sex and opposite-sex peers.

- Popularity: Also measured using peer nominations.

- Romantic Involvement: Self-reported by participants.

- Data Analysis: Path analyses were used to test concurrent and longitudinal associations between bullying and romantic involvement, and the moderating role of popularity.

- Key Quantitative Findings:

Table 3: Key Findings from the Bullying and Romantic Involvement Study [3]

| Variable Relationship | Finding for Boys | Finding for Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Same-Sex Bullying (10th Grade) | Concurrent positive association with romantic involvement. | Concurrent positive association with romantic involvement. |

| Same-Sex Bullying (Longitudinal) | Not predictive of later romantic involvement. | Not predictive of later romantic involvement. |

| Opposite-Sex Bullying (Concurrent) | Associated in 12th grade. | Not specified in snippet. |

| Opposite-Sex Bullying (Longitudinal) | Predictive from 10th to 12th grade. | Predictive from 10th to 12th grade. |

| Moderation by Popularity | Association between bullying and romance was stronger for low-popularity adolescents. | Association between bullying and romance was stronger for low-popularity adolescents. |

The diagram below conceptualizes the information-processing model central to this evolutionary psychology study, where an internal psychological mechanism generates behavior in response to specific environmental inputs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key materials and methodological tools commonly employed in experimental research within these fields.

Table 4: Key Reagents and Methodological Tools for Behavioral Research

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Precisely control the display of images, sounds, or scenarios to participants. | Presenting arrays of plant images in spatial memory tasks [3]. |

| Peer Nomination Surveys | A sociometric method to map social relationships and behaviors (e.g., bullying, popularity) within a closed group like a classroom. | Measuring bullying and popularity status in adolescent studies [3]. |

| Path Analysis / Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | A statistical technique to test complex models of direct and indirect relationships between multiple variables. | Modeling the longitudinal links between bullying, popularity, and romantic outcomes [3]. |

| Video Tracking & Behavioral Coding | Objectively quantify movement, interactions, and other behaviors using automated tracking (e.g., EthoVision) or human coders. | Monitoring insect movement in response to conspecific emissions in a behavioral ecology study [4]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | A analytical chemistry technique used to identify and quantify different compounds within a tested sample. | Analyzing insect pheromone extracts to determine chemical composition [4]. |

The field of behavioral science was fundamentally reshaped in 1975 with the publication of E.O. Wilson's "Sociobiology: The New Synthesis," which proposed a comprehensive biological framework for understanding social behavior across animal species [5]. Wilson defined sociobiology as the "systematic study of the biological basis of all social behaviour" [6], aiming to explain behaviors such as altruism, aggression, and parental care through evolutionary principles. This synthesis suggested that an organism's evolutionary success could be measured by how well its genes are represented in subsequent generations [5]. The work sparked immediate controversy, particularly regarding its application to human behavior, leading to what became known as the "sociobiology wars" [6]. Critics expressed concern that sociobiology promoted genetic determinism and could be used to justify problematic social hierarchies and behaviors as natural and unchangeable [6] [7]. This controversy ultimately catalyzed the fragmentation of sociobiology into distinct, specialized fields including behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology, each developing unique theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches to studying the evolution of behavior.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Divergences

Core Principles of Sociobiology

Sociobiology emerged from the foundational principle that social behaviors evolve through natural selection to enhance reproductive success and genetic representation in future generations [5]. Wilson's approach emphasized that behaviors, like physical traits, could be understood as adaptations that increased the evolutionary fitness of organisms and their genetic relatives. This framework provided evolutionary explanations for seemingly paradoxical behaviors such as altruism, proposing mechanisms like kin selection whereby individuals supporting genetic relatives indirectly promote their own基因 inheritance [6]. The sociobiological perspective initially focused heavily on functional explanations (why a behavior evolved) while paying less attention to proximate mechanisms (how the behavior develops and is expressed) [6]. This emphasis on ultimate evolutionary causes, combined with Wilson's controversial application of these principles to human societies in the first and final chapters of his seminal work, generated significant academic debate and criticism from both biological and social scientists [5].

The Fragmentation into Distinct Fields

The criticisms and limitations of sociobiology prompted researchers to develop more nuanced approaches, leading to the emergence of three primary successor fields [6]:

Behavioral Ecology: This field retained sociobiology's focus on behavioral function and adaptation but placed greater emphasis on ecological constraints and cost-benefit analyses of behavioral strategies in specific environmental contexts [6]. Behavioral ecologists often employ optimality models and evolutionary stable strategy (ESS) models to understand how natural selection shapes behavior in response to environmental pressures [6].

Evolutionary Psychology: This approach shifted focus from behavior itself to the underlying psychological mechanisms and mental modules believed to have evolved during the Pleistocene period (approximately 100,000 to 600,000 years ago) [7]. Evolutionary psychologists propose that humans possess innate, domain-specific cognitive adaptations for solving recurrent problems faced by our ancestors, emphasizing that "modern skulls house a stone age mind" [7].

Dual Inheritance Theory: This framework explicitly incorporates cultural evolution alongside genetic evolution, proposing that humans possess two interacting inheritance systems—genetic and cultural—that jointly shape behavior [6]. This approach addresses a significant limitation of early sociobiology by formally modeling how cultural processes can transmit and evolve behavioral traits.

Table 1: Comparative Theoretical Foundations of Evolutionary Approaches to Behavior

| Aspect | Sociobiology | Behavioral Ecology | Evolutionary Psychology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Biological basis of social behavior [6] | Adaptive function of behavior in ecological context [6] | Evolved psychological mechanisms and mental modules [7] |

| Key Concept | Kin selection, reproductive success [5] | Optimality, cost-benefit analysis [6] | Universal human nature, domain-specific adaptations [7] |

| View on Learning/Culture | Often minimized or seen as evolutionary product [6] | Environmental input to adaptive strategies [6] | Cultural content processed through evolved modules [7] |

| Time Perspective | Evolutionary history of species | Current adaptation to environment [6] | Pleistocene environment of evolutionary adaptedness [7] |

| Methodological Emphasis | Comparative animal behavior [5] | Quantitative models, field studies [6] | Experiments on psychological mechanisms [7] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Characteristic Research Methods by Field

Each field that emerged from sociobiology has developed distinctive methodological approaches aligned with its theoretical focus:

Behavioral Ecology primarily employs field-based observational studies and mathematical modeling to test predictions about adaptive behavior [6]. Researchers typically observe animals in their natural environments to document behavioral patterns and correlate them with ecological variables such as resource availability, predation risk, and mating opportunities. A key analytical tool is the optimality model, which predicts the behavioral strategy that would maximize fitness in a given environmental context [6]. For example, behavioral ecologists might model foraging strategies to understand how animals maximize energy gain while minimizing predation risk. When studying behaviors like the egg-laying strategies of parasitic wasps, researchers employ controlled field experiments to manipulate variables such as the presence of other females' eggs and observe subsequent behavioral changes [6].

Evolutionary Psychology relies heavily on experimental methods derived from cognitive psychology, often conducted in laboratory settings [7]. These experiments typically present human subjects with structured tasks or scenarios designed to activate hypothesized evolved psychological modules. Common approaches include measuring reaction times, memory recall, or perceptual biases in response to evolutionarily relevant stimuli (e.g., threats, potential mates, or social cheaters). Cross-cultural studies are particularly valued for identifying putative universal psychological adaptations that presumably transcend cultural influence [7]. Unlike behavioral ecology, evolutionary psychology generally assumes that the relevant selective pressures occurred in the distant past during the Pleistocene era, making current adaptiveness less crucial to demonstrating evolutionary function [7].

Dual Inheritance Theory utilizes a combination of mathematical models of cultural transmission, experimental economics games, and ethnographic field studies to understand how cultural and genetic evolutionary processes interact [6]. Researchers might develop population models that simulate the spread of cultural traits under different transmission rules (e.g., vertical, horizontal, or oblique transmission) or conduct experiments examining how social learning strategies influence behavioral acquisition and modification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components in Evolutionary Behavioral Research

| Research Component | Function | Field of Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| Optimality Models | Mathematical frameworks predicting behavior that maximizes fitness benefits relative to costs [6] | Behavioral Ecology |

| Evolutionary Stable Strategy (ESS) Models | Game-theoretic approaches identifying behavioral strategies unbeatable by alternatives when common [6] | Behavioral Ecology |

| Standardized Cognitive Tests | Laboratory measures of psychological processing differences for evolutionarily-relevant stimuli [7] | Evolutionary Psychology |

| Cross-Cultural Databases | Systematic collections of behavioral data across diverse societies to test for human universals [7] | Evolutionary Psychology |

| Genetic Relatedness Coefficients | Quantitative measures of kinship used to test predictions of kin selection theory [5] | Behavioral Ecology/Sociobiology |

| Hormonal Assays | Physiological measures of hormone levels (e.g., testosterone, cortisol) to link behavior with biological mechanisms [8] | Multiple Fields |

| Population Genetic Models | Mathematical frameworks simulating allele frequency change under evolutionary forces [6] | Dual Inheritance Theory |

Comparative Analysis of Research Outputs

Interpretation of Key Behavioral Phenomena

The different theoretical perspectives of behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology lead to distinct interpretations and research approaches to similar behavioral phenomena:

Mate Preferences provide a clear example of these divergent approaches. Behavioral ecologists investigate how mate choice varies with ecological conditions, resource availability, and individual state, predicting strategic flexibility in preferences based on current costs and benefits [6]. For instance, research might examine how women's preferences for masculine facial features correlate with environmental factors such as pathogen prevalence or resource scarcity [8]. In contrast, evolutionary psychologists seek evidence for universal mate preference mechanisms, such as hypothesized innate male preferences for signs of fertility like low waist-hip ratios in women [7]. They attribute cross-cultural consistency in certain preferences to species-typical psychological adaptations forged in the Pleistocene environment.

Altruism and Cooperation are similarly explained through different lenses. Behavioral ecology typically employs kin selection theory and reciprocal altruism models grounded in contemporary fitness benefits [6] [5]. Research focuses on how factors like relatedness, future interaction potential, and byproduct benefits maintain cooperative behaviors. Evolutionary psychology instead searches for specialized cognitive adaptations for detecting cheaters in social exchanges—hypothesized "cooperation modules" that evolved to solve recurrent social problems in ancestral environments [7].

Sex Differences in Behavior represent another area of contrasting explanations. Behavioral ecologists often apply parental investment theory to understand how differential investment in offspring leads to different reproductive strategies, predicting behavioral variation based on ecological factors affecting the costs and benefits of various strategies [6]. Evolutionary psychologists are more likely to propose sex-differentiated cognitive modules that developed through different selection pressures on males and females in ancestral environments, sometimes leading to claims about the innate nature of certain behavioral patterns [7].

Conceptual Relationship Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the historical development and conceptual relationships between sociobiology and its descendant fields:

Historical Development from Sociobiology to Descendant Fields

Contemporary Research Applications and Findings

Current Research Directions and Interpretive Differences

Contemporary research in the evolutionary social sciences continues to reflect the distinctive approaches of the fields that emerged from sociobiology, with recent studies highlighting both their productive outputs and persistent tensions:

Human Behavioral Ecology research continues to demonstrate behavioral flexibility in response to ecological conditions. A 2024 study on beauty ideals and socioeconomic status found that preferences for certain physical characteristics shift with regional economic conditions, supporting behavioral ecology's emphasis on context-dependent adaptations [8]. Similarly, research on transactional sex has evolved to incorporate integrated frameworks that consider economic constraints alongside evolutionary motivations, moving beyond simple adaptationist explanations [8].

Evolutionary Psychology research maintains its focus on identifying universal psychological mechanisms. Recent studies have examined whether birth control pills alter women's mate preferences, testing hypotheses about evolved ovulation psychology, though findings challenging initial assumptions highlight ongoing methodological debates within the field [8]. Other research explores how autistic traits correlate with facial masculinity preferences, attempting to link variations in cognitive processing with hypothesized evolved psychological modules [8].

Methodological Innovations across these fields include increasing integration of physiological measures, neuroimaging techniques, and genetic data to bridge the gap between ultimate functions and proximate mechanisms. For instance, studies examining how women read age, adiposity and testosterone levels from male faces combine perceptual experiments with physiological measurements, representing a promising convergence of different evolutionary approaches [8].

Table 3: Representative Contemporary Research Findings from Descendant Fields

| Research Finding | Interpretation | Field |

|---|---|---|

| Women's aggression toward siblings matches or exceeds men's [8] | Challenges simple sex difference models; highlights context specificity of family dynamics | Behavioral Ecology |

| Preferences for lip size shaped by same-gender biases [8] | Suggests intrasexual competition influences beauty standards beyond mate choice | Evolutionary Psychology |

| Attraction to high-status partners depends on status type and relationship context [8] | Supports conditional mating strategies responsive to specific circumstances | Behavioral Ecology |

| Mass murder motivations show different patterns across life stages [8] | Applies evolutionary developmental perspective to extreme violence | Evolutionary Psychology |

| People see kindness as more genetically determined than selfishness [8] | Reveals folk biological intuitions that may reflect essentialist thinking | Dual Inheritance/Cultural Evolution |

The fragmentation of sociobiology into behavioral ecology, evolutionary psychology, and dual inheritance theory has produced a more methodologically sophisticated and theoretically nuanced understanding of the evolution of behavior. While these fields developed distinct research traditions in response to the limitations and controversies of classical sociobiology, contemporary research shows promising signs of integration. The most compelling future direction lies in developing a multilevel evolutionary framework that incorporates both ultimate and proximate explanations, acknowledges the interplay of genetic and cultural inheritance, and recognizes that behaviors reflect both ancient adaptations and contemporary ecological influences. Such an integrated approach would honor the foundational insights of sociobiology while addressing its limitations, potentially leading to a more comprehensive science of human behavior that transcends the divisions that have characterized the field since the "sociobiology wars" of the 1970s.

In 1963, pioneering ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen published a seminal paper, "On the aims and methods of ethology," that would forever change how scientists study behavior [9]. Tinbergen proposed that a comprehensive understanding of any behavioral trait requires addressing four distinct yet complementary biological questions [10] [11]. This framework, now canonized as "Tinbergen's Four Questions," provides a systematic approach for dissecting behavior's complexities while reducing interpretive bias [11]. For researchers navigating the interrelated domains of behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology, Tinbergen's questions offer a unified conceptual scaffold that integrates proximate mechanisms with ultimate evolutionary explanations [10] [12].

Tinbergen's enduring insight was recognizing that biological explanations operate at two distinct levels: proximate (concerned with immediate causation and development) and ultimate (concerned with evolutionary history and adaptive function) [10] [9]. This distinction prevents the common error of confusing explanations at different levels of analysis [12]. Sixty years after their formal articulation, Tinbergen's Four Questions remain remarkably relevant, finding new applications in diverse fields from zoo animal welfare [11] and neuroscience [13] to evolutionary psychiatry [14] and human-oriented disciplines [15]. This guide examines how this framework serves as a powerful unifying lens for behavioral analysis, specifically comparing its application in behavioral ecology versus evolutionary psychology research.

Deconstructing the Framework: The Four Questions Explained

Tinbergen's Four Questions encompass both proximate ("how") and ultimate ("why") explanations for behavior, together providing a comprehensive understanding of any behavioral trait [10] [9]. The following table summarizes the core aspects of each question:

Table 1: Tinbergen's Four Questions Explained

| Question Type | Question Focus | Core Question | Explanatory Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism (Causation) | Immediate triggers & physiological bases | How does the behavior work at physiological and neurological levels? | Proximate |

| Ontogeny (Development) | Individual lifespan development | How does the behavior develop across an individual's lifetime? | Proximate |

| Function (Adaptation) | Survival & reproductive value | Why does the behavior increase survival or reproductive success? | Ultimate |

| Phylogeny (Evolution) | Evolutionary history & ancestry | How did the behavior evolve over evolutionary time? | Ultimate |

Proximate Explanations: How Behavior Works

Proximate explanations focus on the immediate mechanisms and development of behavior within an individual's lifetime [10].

Mechanism (Causation) addresses the immediate stimuli, neurological, hormonal, and anatomical structures that trigger and control a behavior [10] [9]. For example, mechanistic studies might investigate how specialized wind-sensitive hairs on a cockroach's abdomen detect air puffs from a striking predator, triggering neural circuits that initiate escape behavior [9]. In humans, research might examine how neurotransmitters like dopamine or hormones like testosterone influence motivational states or aggressive displays [10].

Ontogeny (Development) explores how a behavior unfolds across an individual's lifespan, including the roles of learning, experience, maturation, and gene-environment interactions [10] [9]. For instance, the Westermarck effect (sexual disinterest in one's siblings) in humans results from familiarity with another individual early in life, particularly during the first 30 months [10]. Similarly, many bird species require specific auditory experiences during critical developmental windows to produce normal adult song [12].

Ultimate Explanations: Why Behavior Evolved

Ultimate explanations examine the evolutionary forces that shaped behavior over deep time [10].

Function (Adaptation) investigates how a behavior enhances survival or reproductive success—its evolutionary "purpose" [10] [9]. Cockroach escape behaviors function to avoid predation [9], while elaborate sage grouse courtship displays function to attract mates and increase reproductive opportunities [9]. Pain and anxiety, while unpleasant, function as adaptive defenses that promote avoidance of harmful situations [14].

Phylogeny (Evolution) reconstructs the evolutionary history of a behavior by comparing related species to trace its origins and modifications [10] [9]. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that the vertebrate eye initially developed with a blind spot due to construction constraints early in evolutionary history, with no adaptive intermediate forms enabling its elimination [10]. Similarly, comparing courtship displays across related grouse species can reveal how complex strutting behaviors evolved from simpler feather erection behaviors [9].

Table 2: Research Approaches for Each of Tinbergen's Questions

| Question | Typical Research Methods | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Neuroimaging, hormonal assays, electrophysiology, pharmacological manipulation | Neural circuits, hormone levels, genetic expression, stimulus-response relationships |

| Ontogeny | Longitudinal studies, cross-sectional comparisons, deprivation experiments, critical period analysis | Developmental trajectories, learning processes, age-dependent changes, experience effects |

| Function | Fitness measurements, experimental manipulation, cost-benefit analysis, optimality modeling | Survival rates, reproductive success, time/energy budgets, adaptive trade-offs |

| Phylogeny | Comparative analysis, cladistics, fossil evidence, molecular phylogenetics | Taxonomic distributions, ancestral state reconstructions, evolutionary sequences |

Tinbergen's Questions in Research Practice: Methodological Applications

Experimental Protocols Across the Four Questions

The following experimental protocols illustrate how researchers systematically address each of Tinbergen's questions:

Protocol 1: Mechanistic Analysis of Escape Behavior [9]

- Objective: Identify neural mechanisms triggering escape behavior in cockroaches.

- Stimulus Presentation: Deliver controlled air puffs to abdominal cerci while monitoring neural activity.

- Neural Recording: Use electrophysiology to trace signal transmission from sensory hairs to giant interneurons.

- Behavioral Measurement: Quantify latency between stimulus and escape initiation using high-speed video.

- Lesion Studies: Selectively disable specific neural pathways to establish necessity.

Protocol 2: Developmental Analysis of Bird Song [12]

- Objective: Determine how early auditory experience shapes adult song in zebra finches.

- Rearing Conditions: Raise nestlings in acoustic isolation, with tutoring, or with restricted auditory exposure.

- Critical Period Manipulation: Vary timing of auditory exposure across developmental stages.

- Song Analysis: Record and quantitatively analyze adult song structure using spectrograms.

- Cross-fostering: Place eggs of one species with parents of another to separate genetic and learned components.

Protocol 3: Functional Analysis of Courtship Displays [9]

- Objective: Establish adaptive function of male sage grouse strutting displays.

- Behavioral Observation: Record display rates, female responses, and mating outcomes on leks.

- Experimental Manipulation: Temporarily alter display characteristics (e.g., reduce feather sound production).

- Fitness Measurement: Track mating success, paternity analysis of offspring.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Quantify energy expenditure and predation risk during displays.

Protocol 4: Phylogenetic Analysis of Parental Care [10]

- Objective: Reconstruct evolution of parental investment patterns in carnivores.

- Comparative Data: Compile parental care behaviors across related species.

- Phylogenetic Tree: Use molecular data to establish evolutionary relationships.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Map character states onto phylogeny to infer evolutionary transitions.

- Correlational Analysis: Identify ecological factors correlated with care pattern evolution.

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between Tinbergen's Four Questions and their integration in behavioral research:

Comparative Analysis: Behavioral Ecology vs. Evolutionary Psychology

While both behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology employ Tinbergen's framework, they differ in emphasis, methodology, and primary research foci. The following table systematically compares how these related disciplines approach behavioral analysis:

Table 3: Tinbergen's Questions in Behavioral Ecology vs. Evolutionary Psychology

| Tinbergen's Question | Behavioral Ecology Emphasis | Evolutionary Psychology Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism (Causation) | Limited focus on cognitive/physiological mechanisms; emphasizes functional outcomes over implementation | Substantial focus on identifying information-processing algorithms and neural implementation of evolved mechanisms |

| Ontogeny (Development) | Interest in developmental plasticity as adaptation to variable environments; learned components of behavior | Focus on innate learning preparedness, critical periods, and obligate vs. facultative adaptations |

| Function (Adaptation) | Primary focus: Detailed cost-benefit analysis, optimality modeling, and fitness consequences in current ecology | Primary focus: Identifying adaptive problems in evolutionary past that shaped domain-specific mental modules |

| Phylogeny (Evolution) | Strong emphasis: Comparative method to reconstruct evolutionary history and identify selection pressures | Moderate emphasis: Uses phylogenetic reasoning but focuses more on species-universal adaptations in humans |

| Typical Research Subjects | Diverse non-human species in natural or semi-natural settings; cross-species comparisons | Humans as primary focus; occasionally other species for comparative insights |

| Temporal Focus | Both current adaptation and evolutionary history; environmental context crucial | Primarily Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA); current manifestations as reflections of past adaptations |

| Key Methodologies | Field observation, experimental manipulation in natural contexts, comparative phylogenetics | Psychological experiments, cross-cultural comparisons, neuroscientific methods, questionnaires |

Case Study Application: Fear Responses

The different emphases of behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology become clear when examining how each would approach fear responses:

Behavioral Ecology Approach:

- Function: Predator avoidance and survival enhancement [9] [11]

- Phylogeny: Comparative studies of anti-predator behavior across related species to trace evolutionary origins [12]

- Mechanism: Neuroendocrine stress axis (less emphasis) [14]

- Ontogeny: Role of early experience with predators and social learning of threat [9]

Evolutionary Psychology Approach:

- Function: Solutions to adaptive problem of detecting and responding to threats in human evolutionary past [14]

- Mechanism: Specific neural circuits (e.g., amygdala) for threat detection; cognitive algorithms for risk assessment [14]

- Ontogeny: Prepared learning to associate certain stimuli (e.g., snakes) with fear more readily [10] [14]

- Phylogeny: Universality across human cultures suggesting deep evolutionary origins [14]

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Behavioral research employing Tinbergen's framework utilizes diverse methodological approaches and technical tools. The following table details key research "reagents" and their applications across the four questions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Tinbergen-Informed Research

| Research Tool/Reagent | Primary Application | Function in Behavioral Analysis | Compatible Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Video Tracking | Quantifying movement kinematics and temporal patterns | Precise measurement of behavior onset, duration, and intensity | Mechanism, Ontogeny, Function |

| Neuroendocrine Assays | Measuring hormone levels (corticosterone, testosterone) | Linking physiological state to behavioral expression | Mechanism, Ontogeny |

| Genetic Sequencing | Identifying genetic correlates of behavior | Establishing phylogenetic relationships and genetic bases | Phylogeny, Mechanism |

| Cross-Fostering Designs | Separating genetic and environmental influences | Disentangling inherited traits from learned components | Ontogeny, Mechanism |

| Phylogenetic Comparative Methods | Statistical analysis of trait evolution across species | Reconstructing evolutionary history of behaviors | Phylogeny, Function |

| Experimental Manipulations | Testing causal hypotheses through intervention | Establishing necessity and sufficiency of mechanisms | Mechanism, Function |

| Environmental Enrichment | Modifying developmental experience | Studying plasticity and behavioral development | Ontogeny, Mechanism |

| Fitness Measurements | Quantifying survival and reproductive success | Establishing adaptive value of behavioral traits | Function |

| Cognitive Testing Paradigms | Assessing information processing and decision-making | Elucidating psychological mechanisms underlying behavior | Mechanism, Function |

| Cross-Cultural Surveys | Identifying human universals vs. cultural variation | Distinguishing evolved adaptations from cultural influences | Phylogeny, Function |

Integration and Synthesis: The Unified Research Workflow

The most powerful applications of Tinbergen's framework occur when researchers integrate all four questions into a cohesive research program. The following diagram illustrates how these questions interconnect in a comprehensive behavioral research workflow:

This integrated approach reveals why Tinbergen's framework remains indispensable sixty years after its formulation: it provides a systematic method for asking complete rather than partial questions about behavior [11] [15]. Research that addresses all four questions can resolve apparent contradictions that arise when behaviors are examined from only a single perspective [12]. For instance, behaviors that appear maladaptive from a functional perspective may reflect developmental constraints or phylogenetic history [10] [12]. Similarly, mechanistic studies alone cannot explain why particular neural circuits evolved rather than possible alternatives [10].

Tinbergen's Four Questions continue to provide a robust foundation for behavioral research across multiple disciplines [11]. By explicitly distinguishing between proximate and ultimate explanations, the framework prevents logical errors and encourages comprehensive research programs that bridge rather than divide biological disciplines [12] [16]. For behavioral ecologists, the questions emphasize that functional and phylogenetic analyses complement rather than replace mechanistic studies [12]. For evolutionary psychologists, the framework ensures that hypotheses about adaptive function remain connected to implementable mechanisms and identifiable evolutionary pathways [14] [15].

As behavioral science progresses, Tinbergen's framework adapts to new discoveries while retaining its core integrative power [12] [11]. Modern extensions sometimes incorporate additional questions about cultural evolutionary processes in humans [15], or refine the relationships among the four questions [16]. However, the fundamental structure remains remarkably unchanged—a testament to Tinbergen's profound insight into the multiple biological explanations required to fully understand behavior [10] [11]. For researchers navigating the complex landscape of behavioral analysis, these four questions continue to provide an indispensable compass—guiding inquiry, preventing conceptual errors, and ultimately unifying our understanding of the beautifully intricate tapestry of animal behavior [12] [11].

A central schism in the evolutionary social sciences lies in the primary goal of explanation: should research aim to uncover the behavioral universals shared by all humans, or to explain the rich behavioral variation observed between individuals and groups? This divide fundamentally structures two major frameworks: evolutionary psychology (EP) and human behavioral ecology (HBE) [17]. Evolutionary psychology seeks to identify species-typical, universal psychological adaptations forged in the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness [17]. In contrast, human behavioral ecology uses optimality models to understand how behavior flexibly responds to variation in socio-ecological contexts, emphasizing behavioral plasticity and local adaptation [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, their methodological tools, and their applicability for research in behavioral ecology and drug development.

Theoretical Frameworks: Core Principles and Objectives

The following table summarizes the foundational differences between the EP and HBE approaches to studying behavior.

Table 1: Core Theoretical Principles of Evolutionary Psychology and Human Behavioral Ecology

| Aspect | Evolutionary Psychology (EP) | Human Behavioral Ecology (HBE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Explanatory Goal | Universal psychological mechanisms [17] | Behavioral variation and phenotypic adaptation [17] |

| Key Constraints | Cognitive, genetic [17] | Ecological, phenotypic (e.g., gender, resources) [17] |

| View on Current Adaptiveness | Often expects "mismatch" with modern environments [17] | Assumes behaviors are generally adaptive to current environments [17] |

| Temporal Focus | Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (deep past) [17] | Contemporary or recent environments [17] |

| Role of Culture | Often a product of universal mechanisms or noise | Primary source of variation and adaptation [18] |

These theoretical differences stem from distinct core assumptions. EP posits that the human brain comprises many domain-specific modules, shaped by natural selection to solve specific problems in our evolutionary past [19] [17]. A key assumption is that modern environments differ significantly from those in which these modules evolved, leading to instances of evolutionary mismatch [17]. HBE, in contrast, often adopts the "phenotypic gambit," assuming that natural selection has endowed humans with general-purpose cognitive abilities that allow for adaptive decision-making in a wide range of current environments without needing to specify the underlying psychological mechanisms [17]. The framework expects that individuals will adopt behavioral strategies that, given local constraints, maximize their reproductive success [17].

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols and Data Collection

The divergent theoretical goals of EP and HBE necessitate different methodological approaches for testing their hypotheses.

Typical Experimental Protocols

Evolutionary Psychology Protocols:

- Cross-Cultural Surveys: Used to identify universal patterns. For example, studies on mate preferences across dozens of cultures test the universalist hypothesis that women, more than men, prioritize resource-acquisition potential in mates [19].

- Laboratory Experiments with Standardized Stimuli: These experiments expose participants from various backgrounds to carefully controlled stimuli (e.g., images of faces, scenarios of risk) to detect universal response patterns in emotions, cognition, or judgment, filtering out cultural noise.

- Psychophysiological Measurement: Protocols measure physiological responses (e.g., heart rate, galvanic skin response, fMRI) to specific stimuli to uncover universal, biologically-rooted psychological mechanisms that may operate below conscious awareness.

Human Behavioral Ecology Protocols:

- Systematic Naturalistic Observation (Immersive Fieldwork): Researchers live within a community, meticulously quantifying behavior and environmental variables. Classic studies involve tracking foraging efficiency—recording what prey is encountered, pursued, and acquired—to test optimal foraging models against real-world data [17].

- Behavioral Coding and Focal Follows: Researchers code specific behaviors (e.g., parenting, cooperation, food sharing) and correlate them with individual characteristics (age, sex, wealth) and ecological contexts (resource abundance, scarcity) to understand adaptive trade-offs [17].

- Demographic and Life History Interviews: Detailed interviews are conducted to collect reproductive histories, kinship networks, and economic transfers. This data tests models of life-history theory, parental investment, and cooperation [17].

Quantitative Analysis of Behavior

Both fields increasingly rely on sophisticated quantitative analysis of behavior, applying mathematical models to experimental and observational data [20] [21]. This branch of analysis was founded by Richard Herrnstein with the introduction of the matching law and integrates models from economics, psychology, and zoology [21]. Key quantitative concepts used in both EP and HBE include behavioral economics (e.g., delay discounting), scalar expectancy theory, and signal detection theory [21]. The emerging field of Applied Quantitative Analysis of Behavior (AQAB) builds on these quantitative theories to address issues of societal concern, such as substance use disorders and medication adherence, making it highly relevant for applied drug development research [20].

Data Synthesis: Comparative Findings in Key Behavioral Domains

The following table contrasts the typical findings and interpretations of EP and HBE across several behavioral domains, highlighting the universals vs. variation dynamic.

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Data and Findings

| Behavioral Domain | Evolutionary Psychology Findings (Universals) | Human Behavioral Ecology Findings (Variation) |

|---|---|---|

| Mate Preferences | A universal tendency for women to value status/resources and men to value youth/health [19] | Marriage strategies (e.g., polygyny vs. monogamy) vary adaptively with resource access and distribution [17] |

| Parental Investment | Universal attachment system between infant and caregiver [19] | Birth spacing and biasing of investment (e.g., son vs. daughter preference) vary with socio-ecology [17] |

| Social Behavior | Universal foundations for reciprocity, kinship-based altruism, and detection of cheaters | Patterns of cooperation, food sharing, and leadership emerge from local payoffs; models show frequency-dependent selection maintains behavioral diversity (e.g., Hawk-Dove game) [18] |

| Risk-Sensitivity & Discounting | Universal tendency toward hyperbolic discounting (preference for immediate rewards) [21] | Rates of delay discounting and risk-taking vary systematically with environmental stability and resource predictability [20] |

Conceptual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the logical pathway from foundational assumption to research outcome that distinguishes the two frameworks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key methodological tools and their functions for conducting research in these fields.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

| Tool or Material | Primary Function | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Cross-Cultural Survey Instruments | To ensure comparability of data across diverse populations for testing universals. | EP: Measuring mate preferences, emotions, or moral judgments in different societies. |

| Behavioral Coding Ethogram | A predefined list of behaviors and operational definitions for systematic observation. | HBE: Quantifying foraging, parenting, or social interactions in field studies. |

| Economic Games (e.g., Ultimatum, Public Goods) | To elicit and measure fundamental social preferences (fairness, cooperation, punishment). | Both: Used in lab settings (EP) and adapted for field contexts (HBE). |

| Delay Discounting Task | A quantitative protocol to measure an individual's preference for smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. | Both: AQAB research on impulsivity in addiction [20]; HBE studies on risk-sensitivity. |

| Demographic Interview Schedule | A structured questionnaire to collect detailed reproductive, kinship, and economic history data. | HBE: Constructing life-history datasets to model fitness trade-offs. |

| Psychophysiological Recording Equipment (e.g., EEG, fNIRS) | To measure physiological correlates of psychological states without relying on self-report. | EP: Identifying universal, non-conscious emotional or cognitive responses. |

While often positioned as rivals, Evolutionary Psychology and Human Behavioral Ecology offer complementary insights. EP excels at identifying the universal cognitive and emotional foundations of behavior, which is crucial for understanding basic reward pathways, stress responses, and social motivations that underpin conditions like addiction and anxiety [19]. HBE provides a powerful framework for understanding how behavioral strategies and health outcomes vary with environmental contexts, such as how socioeconomic status influences discounting rates and medication adherence [20] [17]. For drug development professionals, this means that while our universal human biology (the focus of EP) defines fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters, the striking behavioral diversity highlighted by HBE is key to understanding real-world treatment efficacy and compliance. The integration of both perspectives, supported by robust quantitative analysis, promises a more complete picture of human behavior for developing more effective and personalized interventions.

The 'Phenotypic Gambit' vs. 'Massive Modularity' as Foundational Assumptions

Within the evolutionary behavioral sciences, two foundational assumptions have served as cornerstones for distinct research paradigms: the Phenotypic Gambit in Human Behavioral Ecology (HBE) and the Massive Modularity hypothesis in Evolutionary Psychology (EP). These principles represent fundamentally different starting points for investigating the adaptive nature of human behavior. The Phenotypic Gambit operates as a methodological shortcut that allows researchers to treat phenotypic traits as reasonable proxies for underlying genetic variation when studying adaptation. In contrast, the Massive Modularity hypothesis makes an architectural claim about the human mind, positing it as a collection of hundreds or thousands of specialized, domain-specific computational mechanisms shaped by natural selection to solve problems recurrent in our evolutionary past [22]. This comparison guide examines how these divergent assumptions shape research questions, methodological approaches, and interpretations of human behavior across two prominent evolutionary frameworks.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Foundations

| Aspect | Phenotypic Gambit | Massive Modularity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Field | Human Behavioral Ecology | Evolutionary Psychology |

| Fundamental Premise | Phenotypic variation can be used to study adaptive design without immediate reference to underlying genetics [23] | The mind consists of many innate, domain-specific, specialized information-processing modules [22] |

| View of Mind Architecture | Largely agnostic; focuses on behavioral outcomes | Collection of specialized modules, often likened to a "Swiss Army knife" [22] |

| Primary Research Goal | Understand how behavior contributes to fitness in specific environments | Discover and explain cognitive mechanisms as adaptations to Pleistocene conditions |

| Approach to Learning | Emphasizes adaptive phenotypic plasticity | Focuses on innate cognitive specializations with learning biases |

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Development

The Phenotypic Gambit in Human Behavioral Ecology

The Phenotypic Gambit emerged from behavioral ecology as a pragmatic methodological assumption that enables researchers to study the adaptive value of behaviors without immediately measuring their genetic basis. This approach operates on the premise that phenotypic patterns serve as reasonable proxies for genetic patterns when identifying adaptive behaviors, particularly for traits closely related to fitness [23]. Human Behavioral Ecology, which grew from anthropological traditions in the 1970s, applies this principle to understand human behavioral diversity as adaptive responses to ecological conditions [1]. Researchers in this tradition typically assume that individuals behave in ways that maximize reproductive success in their specific environmental contexts, using phenotypic measurements to test optimality models derived from evolutionary theory [1].

Massive Modularity in Evolutionary Psychology

The Massive Modularity hypothesis represents the core architectural claim of the Evolutionary Psychology research program, which crystallized in the late 1980s and early 1990s through the work of Cosmides, Tooby, and others [22]. This paradigm combines the computational theory of mind (viewing the mind as an information-processing system), adaptationism (explaining traits as products of natural selection), and the claim that the mind comprises numerous domain-specific modules [22]. These modules are understood as cognitive adaptations that evolved in response to characteristically human adaptive problems during the Pleistocene, such as mate selection, kin recognition, and cheat detection [22]. Unlike Fodorian modules which emphasize information encapsulation, Evolutionary Psychology's modules are characterized primarily by domain-specificity and functional specialization.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Paradigms

Research Methodologies in Human Behavioral Ecology

HBE researchers employing the Phenotypic Gambit typically utilize observational field studies and cross-cultural comparisons to examine how behavioral variation correlates with ecological conditions. The experimental protocols often involve:

Behavioral Observation in Natural Settings: Researchers document subsistence strategies, mating behaviors, parental investment, and economic decisions in diverse human populations, particularly in small-scale societies [1].

Optimality Modeling: Scientists develop mathematical models predicting which behavioral patterns would maximize fitness in specific environments, then test these predictions against observed behaviors [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Phenotypic Correlations: Researchers measure associations between behavioral traits and fitness proxies (such as reproductive success or survival) under the assumption that these phenotypic correlations reflect underlying adaptive design [24].

A key methodological strength of this approach is its ability to document behavioral plasticity and understand how environmental variation shapes behavioral strategies across different human populations.

Research Methodologies in Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychologists testing hypotheses about massive modularity employ different experimental protocols, including:

Functional Analysis: Researchers begin with hypotheses about adaptive problems faced by ancestral humans, then design experiments to uncover cognitive mechanisms specialized for solving these problems [22].

Cross-Cultural Psychological Experiments: Studies examine whether people across diverse cultures show predicted specialized cognitive responses to evolutionarily relevant stimuli, such as enhanced recall for cheaters in social exchange scenarios [22].

Developmental and Comparative Methods: Researchers investigate early-emerging cognitive biases in children and compare human cognitive abilities with those of other species to identify specialized adaptations [22].

These methods aim to reveal universal cognitive architecture beneath superficial behavioral variation, emphasizing the domain-specificity of psychological mechanisms.

Critical Empirical Tests and Key Findings

Testing the Limits of the Phenotypic Gambit

The validity of the Phenotypic Gambit has been directly tested through studies that measure both phenotypic and genetic correlations. A landmark cross-fostering experiment with blue tits (Parus caeruleus) revealed critical limitations in this approach:

Experimental Protocol: Researchers conducted a large-scale cross-fostering experiment where nestlings were moved between nests, allowing them to disentangle genetic and environmental influences on phenotypic traits [23].

Key Findings:

- Color traits showed little heritable variation but significant common environment effects

- Skeletal traits demonstrated high heritability with minimal environmental influence

- Positive phenotypic correlations between color and skeletal traits were driven by shared natal environment

- Negative genetic correlations were found between some color and skeletal traits, completely obscured in phenotypic correlations [23]

This study demonstrated that phenotypic patterns can be poor surrogates for genetic patterns, particularly for behavioral and life-history traits with low heritabilities or when trade-offs exist [23]. Recent work has further shown that harsh environments can substantially reduce heritability estimates for behavioral traits, creating conditions where the Phenotypic Gambit is particularly likely to fail in human studies [24].

Evidence Regarding Massive Modularity

The Massive Modularity hypothesis has been tested through numerous psychological experiments, with mixed results:

Supporting Evidence:

- Domain-specific learning biases: Rats more easily associate nausea with taste than with lights or sounds [22]

- Prepared fears: Monkeys more readily acquire fear of snakes than of flowers through observation [22]

- Universal social cognition: Cross-cultural consistency in cheater detection and mate preference patterns [22]

Challenging Evidence:

- Hierarchically Mechanistic Mind (HMM): An alternative model viewing the brain as a complex adaptive system with hierarchical organization rather than a collection of discrete modules [25]

- Network neuroscience: Brain organization shows a balance of functional segregation and global integration that doesn't align neatly with massive modularity [25]

- Free-energy principle: Describes the brain as an inference machine minimizing prediction error through hierarchical processing [25]

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings and Limitations

| Assumption | Supporting Evidence | Contradictory Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic Gambit | Works well for highly heritable morphological traits [23] | Fails for low-heritability traits; obscured by environmental correlations and trade-offs [23] [24] |

| Massive Modularity | Domain-specific learning biases; universal cognitive patterns [22] | Hierarchical brain organization; integrated neural dynamics; developmental plasticity [25] |

Integrative Approaches and Contemporary Syntheses

Contemporary research increasingly recognizes the limitations of both foundational assumptions and seeks integrative approaches:

Beyond the Phenotypic Gambit

Researchers are developing methods that combine behavioral ecology with behavioral genetics to overcome limitations of the Phenotypic Gambit:

Integrated Research Design:

- Partition genetic and environmental variances for behavioral traits

- Measure genetic correlations between traits and fitness proxies

- Analyze ecological conditions as moderators of heritability [24]

This approach is particularly valuable for understanding how harsh environments affect the expression and heritability of behavioral traits, offering more nuanced insights into human behavioral adaptation [24].

Evolving Understanding of Neural Organization

The Hierarchically Mechanistic Mind (HMM) represents a promising synthesis that incorporates insights from both evolutionary psychology and neuroscience:

Key Principles of HMM:

- The brain functions as a complex adaptive system minimizing entropy of sensory states [25]

- Hierarchical organization with repeated encapsulation of smaller neural elements in larger ones [25]

- Balance between functional specialization and global integration [25]

- Neural subsystems characterized by hierarchical near-decomposability rather than strict encapsulation [25]

This perspective aligns with the free-energy principle, which provides a mathematical framework for understanding brain function across spatiotemporal scales [25].

Essential Research Tools and Methodological Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Behavioral Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-fostering Designs | Disentangles genetic and environmental influences on phenotypic traits | Testing phenotypic gambit assumptions [23] |

| Twin and Family Studies | Quantifies heritability and partitions genetic/environmental variance | Integrated behavioral genetics approaches [24] |

| Optimality Modeling | Develops testable predictions about fitness-maximizing behaviors | Human Behavioral Ecology [1] |

| Standardized Cognitive Tasks | Measures domain-specific cognitive performance across populations | Evolutionary Psychology [22] |

| Neuroimaging (fMRI, EEG) | Maps neural correlates of cognitive processing and hierarchical organization | Testing alternative models like HMM [25] |

| Cross-cultural Protocols | Identifies universal patterns versus cultural variations in behavior | Both HBE and EP [1] |

The Phenotypic Gambit and Massive Modularity represent distinct foundational assumptions that have guided research in Human Behavioral Ecology and Evolutionary Psychology respectively. The Phenotypic Gambit offers methodological practicality for studying behavioral adaptation but faces limitations when phenotypic correlations poorly reflect genetic relationships, particularly for low-heritability traits or under harsh environmental conditions [23] [24]. The Massive Modularity hypothesis effectively highlights domain-specific cognitive adaptations but struggles to account for the hierarchical, integrated organization of neural systems revealed by contemporary neuroscience [25] [22].

Future research appears headed toward integrative approaches that combine the strengths of both paradigms while acknowledging their limitations. The incorporation of behavioral genetics into human behavioral ecology addresses critical weaknesses in the Phenotypic Gambit [24], while frameworks like the Hierarchically Mechanistic Mind incorporate evolutionary thinking with modern understanding of neural dynamics [25]. This synthesis promises a more complete understanding of human behavior—one that recognizes both specialized cognitive adaptations and the flexible, integrated nature of the neural systems that generate them.

Research Practices and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

In the scientific study of human behavior, two methodological approaches offer distinct pathways to knowledge: field observation and psychological experimentation. Framed within the broader theoretical debate between behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology, these toolkits represent fundamentally different philosophies about how to best understand why humans think and act as they do. Human behavioral ecology (HBE) investigates how adaptive human behavior maps onto variation in social, cultural, and ecological environments, emphasizing behavioral flexibility in response to current conditions [17]. In contrast, evolutionary psychology (EP) seeks to identify the evolved psychological mechanisms adapted to long-term environments of evolutionary adaptedness, often emphasizing universal cognitive structures [17]. This methodological comparison guide objectively examines the research tools, experimental protocols, and applications of these complementary approaches to provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting appropriate methods based on their specific research questions within the evolutionary social sciences.

Theoretical Foundations and Research Goals

Human Behavioral Ecology: Understanding Adaptive Flexibility

Human behavioral ecology starts from the premise that human behavior represents adaptive responses to contemporary socio-ecological conditions. HBE researchers use optimality frameworks to understand how people modify behaviors in response to environmental variation, asking how costs and benefits of different behaviors are navigated to maximize reproductive success given specific constraints [17]. This theoretical perspective anticipates that humans will generally adopt behavioral strategies with the highest net benefits in their specific environment, leading to predictable behavioral variation across different ecological contexts. HBE emphasizes phenotypic plasticity and expects that what maximizes fitness for one individual may differ for another based on gender, resources, social status, and local ecology [17].

The primary methodological implication of this theoretical orientation is the preference for naturalistic field observation that captures behavior in real-world contexts where these adaptive decisions naturally occur. HBE seeks to explain behavioral diversity rather than universals, with its historical roots in immersive fieldwork within small-scale societies, though contemporary HBE research now encompasses industrialized populations [17].

Evolutionary Psychology: Identifying Evolved Mechanisms

Evolutionary psychology focuses on identifying the evolved psychological mechanisms that constitute "human nature" [17]. Unlike HBE's emphasis on contemporary adaptiveness, EP emphasizes longer-term, genetically-driven evolutionary processes that may create mismatch between contemporary environments and evolved psychological adaptations [17]. This perspective typically views the mind as composed of specialized domain-specific modules rather than general-purpose cognitive structures, with these mechanisms shaped by consistent selection pressures in our evolutionary past rather than current environmental conditions [17].

This theoretical foundation leads evolutionary psychologists to prefer controlled experimentation that can isolate and identify these putative universal psychological mechanisms. By manipulating specific variables in laboratory settings, EP researchers attempt to reveal cognitive adaptations that operate across diverse human populations, presuming these mechanisms to be part of a universal human nature [17].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations of Behavioral Ecology and Evolutionary Psychology

| Aspect | Behavioral Ecology Framework | Evolutionary Psychology Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Explanatory Focus | Behavioral variation across environments | Universal psychological mechanisms |

| Key Constraints | Ecological, phenotypic (e.g., gender, resources) | Cognitive, genetic architectures |

| Temporal Scale of Adaptation | Short-term (phenotypic flexibility) | Long-term (evolutionary history) |

| Expected Current Adaptiveness | Generally adaptive to current environment | Possibly mismatched with modern environment |

| View of Cognitive Mechanisms | General-purpose problem solving | Domain-specific psychological modules |

Complementary Perspectives in Modern Research

While these theoretical perspectives differ in their starting assumptions and methodological preferences, contemporary research increasingly recognizes their complementary value. As Smith [17] notes, current trends in these disciplines show more convergence than their historical emphases might suggest. Many researchers now integrate elements of both approaches, using field observation to identify behavioral patterns in natural contexts followed by controlled experiments to test specific hypotheses about underlying mechanisms. This integrative approach acknowledges both the context-dependent nature of many behaviors and the existence of species-typical psychological adaptations.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Field Observation: Capturing Natural Behavior in Context

Field observation encompasses a range of systematic data collection methods conducted in natural settings rather than controlled laboratories. These methods aim to minimize researcher interference to capture authentic behaviors as they naturally occur [26] [27].

Direct Observation involves researchers observing subjects in their natural environment without interaction or manipulation of the setting [26]. This approach captures real-time behavior with minimal interference, providing high ecological validity [26]. Protocol implementation requires careful pre-definition of behavioral categories, systematic recording procedures, and strategies to minimize observer effects on natural behavior.

Participant Observation occurs when researchers become part of the environment being studied, participating in activities while observing them from within [26]. This immersive approach builds trust and provides insider perspectives but risks researcher bias through over-identification with subjects [26]. Standard protocols include gradual integration into the community, reflective journaling, and triangulation of observations across multiple sources.

Ethnographic Research constitutes an in-depth exploration of a group or culture through extended observation, focusing on interaction patterns within social settings [26]. This method reveals social norms and cultural influences through prolonged engagement (often months or years), detailed field notes, and iterative analysis moving between observation and interpretation.

Natural Experiments observe the effects of naturally occurring events or situations on dependent variables without researcher manipulation [28]. For example, researchers might compare populations affected and unaffected by a natural disaster or policy change [28]. These studies provide high ecological validity and can address questions where deliberate manipulation would be unethical [28].

Psychological Experimentation: Establishing Causal Mechanisms

Psychological experimentation involves deliberate manipulation of variables to establish cause-and-effect relationships under controlled conditions [29] [28]. The key features include controlled methods, random allocation of participants, and systematic manipulation of independent variables [28].

Laboratory Experiments are conducted under highly controlled conditions where researchers manipulate independent variables and measure effects on dependent variables [28]. These experiments use standardized procedures specifying where the experiment takes place, at what time, with which participants, and under what circumstances [28]. Key protocols include random assignment to conditions, control of extraneous variables, and implementation of blinding procedures to minimize demand characteristics and experimenter effects [28].

Field Experiments represent a hybrid approach where researchers manipulate independent variables in natural, real-world settings [28]. Participants are often unaware they are being studied, providing more natural behavior while maintaining some experimental control [28]. These experiments are particularly valuable for studying social phenomena and testing intervention effectiveness in applied contexts [28].

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard for establishing causal relationships in experimental research [30] [31]. In RCTs, eligible participants are randomly assigned to experimental or control groups, with the experimental group receiving the intervention and the control group receiving nothing, a placebo, or standard care [30]. This design minimizes confounding by distributing both known and unknown risk factors equally across groups through randomization [31].

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Applications

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

| Aspect | Field Observation | Psychological Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Validity | High - behavior observed in natural contexts [26] [27] | Variable - often lower, especially in lab settings [28] |

| Internal Validity/Causation | Limited - cannot firmly establish causality due to confounding [30] [29] | High - strong causal inference through manipulation and control [29] [28] |

| Risk of Bias | Researcher bias in interpretation; participant reactivity [26] [27] | Demand characteristics; experimenter effects [28] |

| Data Richness | High - detailed, contextual, nuanced behavioral data [26] [27] | Focused - specific, quantifiable measures of target variables [28] |

| Time Requirements | High - often requires extended engagement [26] [27] | Variable - typically shorter-term data collection [29] |

| Sample Considerations | Often smaller, purposefully selected [26] [27] | Can achieve larger samples through efficient design [29] |

| Resource Requirements | Can be costly due to travel, extended fieldwork [26] | Variable - lab equipment, participant compensation [29] |

| Flexibility | High - adaptable to emerging findings during research [26] | Low - requires strict protocol adherence [28] |

Appropriate Research Contexts

Field observation is particularly appropriate when studying natural phenomena in real-world contexts [29], investigating rare events that cannot be replicated in laboratory settings [29], examining long-term effects and developmental trajectories [29], exploring sensitive topics where experimental manipulation would be unethical [30] [29], and conducting initial exploratory research to generate hypotheses [26]. From a behavioral ecology perspective, field methods are essential for understanding how behaviors function in specific socio-ecological contexts [17].

Psychological experimentation is preferred when establishing cause-and-effect relationships is paramount [29] [28], testing specific hypotheses derived from theory [29] [28], controlling extraneous variables to isolate mechanisms [28], studying short-term effects of interventions [29], and when random assignment is ethically and practically feasible [29]. From an evolutionary psychology perspective, controlled experiments are invaluable for revealing universal psychological mechanisms [17].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Field Observation Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Resources for Field Research

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Field Notes System | Systematic recording of observations, behaviors, and contextual details | Structured logs, behavioral coding sheets, reflexive journals [27] |

| Audio/Video Recording Equipment | Capture raw behavioral data for later analysis | Recording natural interactions, environmental contexts, nonverbal behaviors [26] |

| Qualitative Interview Guides | Collect participant perspectives and experiential accounts | Understanding subjective experiences, cultural meanings, personal motivations [26] |

| Field Service Management Software | Organize and manage field data collection | Coordinating multiple observers, managing location-based data [26] |

| Ethnographic Database Software | Code and analyze qualitative data | Identifying thematic patterns across extensive field notes [26] |

Experimental Research Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Resources for Experimental Research

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization Protocol | Assign participants to conditions without bias | Random number generators, block randomization procedures [30] [28] |

| Experimental Manipulation Materials | Implement independent variable manipulations | Drug administration protocols, psychological priming stimuli, task instructions [28] |

| Dependent Measure Instruments | Quantify outcomes and effects | Psychometric scales, reaction time recording, physiological measures, behavioral observation coding [28] |

| Control Condition Materials | Provide appropriate comparison baseline | Placebo preparations, neutral control stimuli, attention-control tasks [30] [28] |

| Blinding Procedures | Minimize experimenter and participant bias | Double-blind protocols, automated data collection, standardized instructions [28] |

Integration and Future Directions

The most compelling research in human behavior often integrates both observational and experimental approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths [29]. Sequential designs might begin with field observation to identify naturally occurring behavioral patterns and generate ecologically-grounded hypotheses, followed by controlled experiments to test causal mechanisms suggested by the observational findings [29]. Simultaneous designs might combine experimental manipulation with naturalistic observation, such as conducting field experiments that introduce subtle interventions in real-world contexts [28].