Behavioral Plasticity: From Neural Mechanisms to Therapeutic Innovation in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of behavioral plasticity, the capacity of an organism to adapt its behavior to environmental changes, internal states, and experience.

Behavioral Plasticity: From Neural Mechanisms to Therapeutic Innovation in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of behavioral plasticity, the capacity of an organism to adapt its behavior to environmental changes, internal states, and experience. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore its foundational principles, including key distinctions between developmental and activational plasticity, and its underlying neurobiological mechanisms involving BDNF, synaptic proteins, and neural circuits. The content details advanced methodological approaches for its study, examines the challenges and costs associated with plasticity, and validates its significance through comparative evolutionary analysis and its direct relevance to contemporary neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric drug development pipelines. The synthesis offers a roadmap for leveraging behavioral plasticity as a transformative target in therapeutic development.

Defining Behavioral Plasticity: Core Concepts, Classifications, and Neurobiological Substrates

Behavioral plasticity is formally defined as the capacity of an organism to modify its behavior in response to exposure to stimuli, such as changing environmental conditions or internal states [1]. This adaptive capability serves as a critical survival mechanism, allowing individuals to adjust their actions more rapidly than is possible through morphological or physiological changes alone [1]. The conceptual framework of behavioral plasticity occupies a central position in evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and psychology, representing a type of phenotypic plasticity with significant consequences for understanding how organisms navigate variable environments [1]. From a research perspective, the study of behavioral plasticity integrates multiple levels of analysis—from molecular genetics to neurobiology and ecology—to decipher how organisms generate flexible behavioral responses with adaptive value [2] [3].

The fundamental importance of behavioral plasticity lies in its temporal advantage; behavioral changes can occur within moments to hours of encountering new conditions, while morphological adaptations may require generations to evolve [1]. Empirical evidence demonstrates this dramatic timescale difference: larval amphibians were observed to alter their antipredator behavior within an hour after detecting predator cues, whereas morphological changes in body and tail shape in response to the same cues required approximately one week to complete [1] [4]. This rapid response capability makes behavioral plasticity a first line of defense and adaptation in fluctuating environments, providing organisms with immediate tools for survival while potentially buying time for slower-acting evolutionary processes to unfold [1] [5].

Classification and Types of Behavioral Plasticity

Behavioral plasticity can be categorized through several classification systems based on the nature of the triggering cues, the temporal characteristics of the response, and the underlying mechanisms involved. These classifications provide researchers with a structured framework for designing experiments and interpreting results related to behavioral flexibility across taxa.

Primary Classification Frameworks

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Behavioral Plasticity

| Classification | Definition | Timescale | Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Plasticity | Behavioral changes driven by external stimuli, such as social or physical environmental factors [1] [3] | Variable | Ants rapidly altering running speed in response to changes in external temperature [1] |

| Endogenous Plasticity | Behavioral changes driven by internal factors, such as hormonal cycles, circadian rhythms, or genotype [1] [3] | Variable | Zebrafish showing circadian rhythms in light responsiveness even under continuous darkness [1] |

| Contextual Plasticity | Immediate behavioral changes activated by existing neural pathways in response to current environmental context [1] [3] | Seconds to hours | Birds changing vocalizations in response to background noise pitch or intensity [1] |

| Developmental Plasticity | Long-term behavioral changes resulting from past experiences during sensitive developmental periods [1] [3] | Lifetime | Moth larvae reared at different densities producing different courtship signals as adults [1] |

| Activational Plasticity | Rapid activation or suppression of behaviors in response to immediate cues [5] | Immediate to short-term | Switch between foraging and anti-predator behaviors based on predator presence [5] |

Characteristics and Trade-offs

Different types of behavioral plasticity involve distinct mechanistic bases and evolutionary trade-offs. Contextual plasticity utilizes pre-existing neural and hormonal pathways that can be activated immediately without structural changes to the nervous system [1]. This provides the advantage of rapid response but may be limited in the novelty of behaviors it can produce. In contrast, developmental plasticity often requires the formation of new neuronal pathways and can involve coordinated changes across suites of behavioral, morphological, and physiological traits [1]. While generally slower to manifest, developmental plasticity can produce more permanent and comprehensive phenotypic adjustments tailored to environmental conditions experienced during critical developmental windows [1] [6].

The distinction between reversible and irreversible plasticity further refines our understanding of behavioral flexibility [5]. Reversible plasticity allows organisms to switch between behavioral states as conditions fluctuate, such as birds alternating between territorial and flocking behaviors based on resource availability [5]. Irreversible plasticity, often resulting from early life experiences like imprinting, produces persistent behavioral phenotypes that remain stable throughout the lifespan regardless of subsequent environmental changes [5]. This irreversibility may be adaptive when early cues reliably predict lifelong environmental conditions but maladaptive when conditions change dramatically later in life [6].

Neurobiological and Molecular Mechanisms

The neurobiological basis of behavioral plasticity encompasses multiple levels of neural organization, from molecular changes within individual neurons to large-scale circuit reorganizations. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for researching how genetic programs and environmental experiences interact to generate adaptive behavioral responses.

Neural Circuit and Synaptic Mechanisms

At the synaptic level, long-term potentiation (LTP) serves as a fundamental mechanism for strengthening synaptic connections in response to repeated activation, providing a cellular basis for learning and memory formation [1]. Complementary to this, dendritic spine remodeling enables structural changes in neural connectivity, allowing for the physical reorganization of neural circuits in response to experience [1]. Additionally, adult neurogenesis in specific brain regions like the hippocampus contributes to behavioral plasticity by incorporating new neurons into existing circuits, potentially enabling more flexible responses to novel situations [1]. These synaptic-level mechanisms collectively provide the foundation for experience-dependent modification of neural circuits that underlie behavioral adaptation.

Neurochemical Signaling Pathways

Neurochemical systems mediate behavioral plasticity through multiple signaling pathways that modulate neural activity and connectivity. The dopaminergic system plays a central role in reward-based learning, reinforcing behaviors that lead to positive outcomes [1]. Serotonergic signaling is implicated in social and stress-related behavioral plasticity, modulating responses to social cues and environmental challenges [1]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates stress-induced behavioral flexibility through cortisol (corticosterone in rodents) release, enabling organisms to adjust their behavior under stressful conditions [1]. At the molecular level, gene expression changes and epigenetic regulation mechanisms, including transcription factors like CREB and neurotrophins such as BDNF, mediate long-term storage of learned experiences by altering the molecular composition of neurons [1].

Brain Systems and Regional Specialization

Distinct brain regions contribute specialized functions to the overall capacity for behavioral plasticity. The prefrontal cortex provides executive control and behavioral flexibility, enabling organisms to override automatic responses and implement context-appropriate behaviors [1]. The amygdala plays a key role in emotionally driven learning, particularly in forming associations between neutral stimuli and emotionally significant events [1]. The hippocampus supports contextual learning and memory, allowing organisms to recognize and respond appropriately to specific environmental contexts [1]. The basal ganglia contribute to habit formation and motor learning, enabling the automatization of frequently performed behaviors to free cognitive resources for novel challenges [1]. The complexity of an organism's nervous system directly influences its behavioral repertoire, with more complex neural architectures generally supporting more diverse and nuanced forms of behavioral plasticity [1].

Research Models and Methodological Approaches

Experimental research into behavioral plasticity employs diverse model organisms and methodological approaches, each offering unique advantages for investigating specific aspects of behavioral flexibility across different timescales and biological levels of organization.

Model Organisms in Behavioral Plasticity Research

Table 2: Key Model Organisms and Their Research Applications

| Model Organism | Research Advantages | Forms of Plasticity Studied | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis elegans | Compact nervous system (302 neurons), fully mapped connectome, genetic tractability [4] [2] | Habituation, sensitization, classical conditioning, sensory adaptation [4] [2] | Identified conserved molecular pathways in learning and memory [2] |

| Rodents (Rats/Mice) | Complex brains with mammalian features, established behavioral assays, genetic manipulation possible [1] [6] | Maternal effects, stress responses, learning and memory, predictive adaptive responses [1] [6] | Maternal licking/grooming affects offspring stress reactivity via epigenetic mechanisms [6] |

| Daphnia spp. | Clearly defined predator-induced morphological and behavioral changes [6] | Inducible defenses, adaptive phenotypic switching | Develop protective helmets when exposed to predator kairomones [6] |

| Amphibians (Frogs/Salamanders) | Susceptibility to environmental cues during larval stages [1] [6] | Antipredator behavior, developmental plasticity | Rapid behavioral changes (hours) vs. morphological changes (weeks) following predator exposure [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Research into behavioral plasticity employs carefully designed experimental protocols to isolate specific forms of plasticity. For studying developmental plasticity, researchers typically divide matched individuals into multiple groups that are reared under different environmental conditions, then compare their behavioral phenotypes later in life [1]. This approach demonstrated that moth larvae raised at different densities developed different courtship signals as adults [1]. For investigating contextual plasticity, the same individual is presented with different external stimuli while researchers quantify the behavioral responses to each stimulus, as commonly done in mate preference studies [1].

The tap withdrawal response in C. elegans provides a well-characterized protocol for studying habituation learning [4]. Researchers deliver repeated mechanical stimuli to the substrate containing the worms while quantifying the decline in reversal response magnitude [4]. This paradigm has been adapted to study both short-term and long-term memory by varying the interstimulus interval and training intensity [4]. For studying predictive adaptive responses in mammals, researchers often manipulate the maternal environment during gestation (e.g., through nutritional restriction or stress exposure) and track the offspring's physiological and behavioral responses to different postnatal environments [6].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tools | Mutant strains, RNAi constructs, CRISPR-Cas9 systems [4] [2] | Gene function manipulation in behavioral pathways | C. elegans learning mutants, rodent knockout models [2] |

| Neural Activity Reporters | GCaMP calcium indicators, channelrhodopsins for optogenetics [2] | Neural activity visualization and manipulation | In vivo imaging of learning-related neural circuits [2] |

| Behavioral Assay Systems | Olfaction mazes, tap withdrawal apparatus, conditioned place preference setups [4] | Standardized behavioral quantification | Habituation measurement in C. elegans [4] |

| Chemical Stimuli | Odorants (benzaldehyde, diacetyl), salts, pheromones [4] [2] | Controlled sensory stimulation | Olfactory learning, chemotaxis plasticity assays [2] |

| Environmental Manipulation Systems | Controlled temperature gradients, custom olfactory environments [2] | Precise environmental control | Thermotaxis plasticity studies [2] |

Evolutionary Framework and Adaptive Significance

Behavioral plasticity has profound evolutionary implications, influencing how populations adapt to changing environments and potentially altering evolutionary trajectories. The adaptive value of behavioral plasticity is particularly evident in fluctuating environments, where fixed behavioral strategies may be insufficient for long-term survival and reproductive success [1] [5].

Fitness Consequences and Adaptive Value

The evolutionary fitness of behavioral plasticity depends critically on the match between an organism's behavioral phenotype and its environmental conditions [1] [6]. Behavioral plasticity enhances fitness by enabling organisms to adjust their behavior to current conditions, such as modifying foraging strategies when food availability changes or altering anti-predator behavior when threat levels fluctuate [5]. The Predictive Adaptive Response (PAR) hypothesis specifically proposes that cues received during early development shape a phenotype that is adapted to predicted future environmental conditions [6]. When the predicted and actual environments match, this developmental programming enhances fitness; when mismatched, it can lead to health problems and reduced fitness [6]. Evidence for PARs includes observations that vole pups born in autumn develop thicker coats than spring-born pups, based on maternal hormonal signals reflecting day length—an adaptation that improves winter survival [6].

However, behavioral plasticity also entails costs and constraints that limit its evolution [5]. Maintaining the neural and physiological machinery necessary for behavioral flexibility requires energy and resources that could otherwise be allocated to growth, reproduction, or other functions [5]. Additionally, the time and energy invested in learning new behaviors or assessing environmental cues may outweigh the benefits in stable environments where fixed behaviors would be sufficient [5]. These costs create evolutionary trade-offs that shape the extent and nature of behavioral plasticity in different species and ecological contexts.

Correlated Behavioral Plasticities and Evolutionary Trajectories

Recent research has revealed that plasticity in different behavioral traits is often correlated, forming correlated behavioral plasticities that may influence evolutionary processes [7]. These correlations mean that selection acting on plasticity in one behavior may produce evolutionary changes in plasticity in other, correlated behaviors [7]. Such correlated plasticities are particularly important in contexts like sexual and social signaling, where multiple behavioral components must be coordinated to produce effective communicative displays [7].

Behavioral plasticity can influence evolutionary trajectories by facilitating population persistence in novel environments and potentially paving the way for subsequent genetic adaptation [5]. This process, sometimes termed "evolutionary rescue," is particularly important for long-lived species with slow generation times, for whom genetic adaptation may be too slow to track rapid environmental changes [3]. In some cases, behavioral plasticity can also promote speciation by enabling populations to exploit new ecological niches or develop novel mating preferences that reduce gene flow between populations [5].

Applications and Research Implications

Understanding behavioral plasticity has significant practical applications across multiple fields, from conservation biology to biomedical research and drug development. The insights gained from basic research on behavioral flexibility are increasingly informing strategies for addressing pressing challenges in human health and environmental management.

In conservation and wildlife management, knowledge of behavioral plasticity helps predict how species may respond to anthropogenic disturbances, habitat modifications, and climate change [5]. Conservation strategies can leverage this understanding to design more effective protected areas, mitigate human-wildlife conflicts, and optimize captive breeding and reintroduction programs [5]. For example, understanding the developmental plasticity of habitat preferences can inform strategies for acclimating animals to new environments before release [5].

In biomedical research and drug development, insights into the molecular and neural mechanisms of behavioral plasticity inform the search for novel therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders characterized by maladaptive behavioral rigidity, such as addiction, depression, and anxiety disorders [1] [6]. Research on epigenetic mechanisms in behavioral plasticity has been particularly fruitful, revealing how early life experiences produce lasting changes in gene expression that influence stress responsiveness and vulnerability to mental health disorders [6]. The C. elegans model system continues to provide fundamental insights into conserved molecular pathways in learning and memory that may identify novel targets for cognitive enhancement or neuroprotective therapies [2].

Future research directions include leveraging advanced tracking technologies to collect rich datasets on behavioral variation in natural contexts, applying reaction norm approaches to quantify plasticity across multiple traits and environments, and integrating across biological levels from genes to ecosystems to develop a comprehensive understanding of behavioral plasticity's causes and consequences [7]. These approaches will further illuminate how behavioral flexibility develops, evolves, and functions across diverse species and ecological contexts.

Behavioral plasticity, the capacity of an organism to alter its behavior in response to stimuli, represents a fundamental adaptive strategy across species [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the mechanistic underpinnings of behavioral plasticity is crucial for developing interventions targeting maladaptive behavioral responses. This guide establishes a rigorous technical framework for classifying plasticity into two distinct but sometimes interacting types: developmental plasticity and activational plasticity [8] [9]. This dichotomy is not merely semantic; it reflects profound differences in underlying neural mechanisms, temporal scales, and evolutionary costs, each with significant implications for therapeutic development [8]. Developmental plasticity refers to the capacity of a genotype to adopt different developmental trajectories in different environments, resulting in relatively permanent changes to the nervous system [1] [8]. In contrast, activational plasticity involves the differential activation of an existing neural network by different environmental cues, enabling an individual to express various phenotypes throughout its lifetime without permanent structural changes [8] [9]. This classification provides a powerful lens through which to examine how experiences, from early life to adulthood, shape behavioral outcomes and potential.

Core Definitions and Comparative Analysis

Developmental Plasticity

Developmental plasticity occurs when a genotype expresses different behavioral phenotypes based on different developmental trajectories triggered by environmental conditions [8]. This form encompasses processes often described as 'learning,' where experiences during critical developmental windows shape the nervous system, leading to enduring behavioral changes [1]. A key example is found in moth larvae (Manduca sexta), where the density at which they are raised experimentally affects the courtship signals they produce as adults [1]. This plasticity involves not only changes in neural circuitry but also coordinated changes in relevant morphological and physiological traits [1]. From a clinical perspective, early life constraints, such as intra-uterine growth conditions, can program phenotypes that manifest later in life as disorders like diabetes and hypertension, a phenomenon described as Predictive Adaptive Response (PAR) [10].

Activational Plasticity

Activational plasticity, meanwhile, involves the immediate or rapid activation of pre-existing neural networks and physiological systems by specific internal or external cues [8] [9]. This allows an organism to toggle between different behavioral states throughout its life without undergoing permanent structural changes. A straightforward example is an ant's ability to rapidly alter its running speed in response to changes in ambient temperature [1]. This form of plasticity is often reversible and context-dependent, leveraging neural and hormonal pathways that are already present and functional [1]. Activational plasticity can be further subdivided into exogenous (driven by external stimuli) and endogenous (driven by internal states like circadian rhythms or hormonal cycles) forms [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Developmental and Activational Plasticity

| Feature | Developmental Plasticity | Activational Plasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Different developmental trajectories triggered by the environment lead to different phenotypes [8]. | Differential activation of an existing network leads to different expressed phenotypes [8]. |

| Temporal Scale | Slow, often involving critical periods; changes are long-lasting [1] [8]. | Rapid, immediate behavioral responses; changes are often transient [1]. |

| Underlying Mechanism | Changes in neural architecture, including formation of new neuronal pathways; trial-and-error learning [1] [8]. | Activation of existing hormonal networks and neuronal pathways [1]. |

| Permanence | Relatively permanent or enduring [8]. | Reversible and flexible [8]. |

| Primary Cost | Energetic cost of trial-and-error development and maintaining a wider range of potential phenotypes [8]. | Energetic cost of maintaining large, versatile neural networks past initial development [8]. |

| Evolutionary Selection | Coarse-grained environmental variation [8]. | Fine-grained environmental variation [8]. |

| Example | Moth larval density affecting adult courtship signals [1]; early life nutrition affecting adult male reproductive strategies [10]. | Ants changing running speed with temperature; birds adjusting vocalizations to background noise [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Plasticity Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function / Utility | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Optogenetics | Selective activation or inhibition of specific neural pathways (e.g., D1 vs. D2 MSNs) [11]. | Established that activating D1 MSNs initiates locomotion, while activating D2 MSNs ceases it, confirming their competing roles [11]. |

| Dopamine Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacological manipulation of dopamine signaling to probe its role as a reinforcement prediction error signal [11]. | Key for validating the complex, multi-factor model of cortico-striatal plasticity, where dopamine level, receptor type, and spike timing interact [11]. |

| Knockout/Transgenic Models | Studying the role of specific genes and neuropeptides (e.g., opioids, orexin, NPY, oxytocin) in feeding behavior and plasticity [9]. | Reveals how neuropeptide systems influence behavioral plasticity in response to factors like time of day, food type, and stressors [9]. |

| Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity (STDP) Protocols | In vitro electrical stimulation to induce and map synaptic plasticity rules [11] [12]. | Uncovered the three-way interaction between pre/post-synaptic spike timing, dopamine level, and receptor type governing cortico-striatal LTP/LTD [11]. |

| Operant Conditioning Chambers | Standardized environments (e.g., rodent lever-pressing) to study the acquisition and extinction of goal-directed actions [11]. | Provides behavioral data on learning and extinction that can be correlated with neural activity changes in striatum [11]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Differentiating Plasticity Types in Animal Models

This protocol is designed to empirically distinguish developmental from activational plasticity in a controlled laboratory setting, using the rearing density of moth larvae and its effect on adult courtship as a paradigm [1].

- Subject & Housing: Utilize a genetically similar population of moth larvae (Manduca sexta). Randomly assign subjects to one of three rearing conditions:

- Group A (High Density): House larvae at a high density.

- Group B (Low Density): House larvae at a low density.

- Group C (Cross-Over): House larvae at a high density initially, then transfer to low density (or vice-versa) at a specific developmental stage (e.g., after the third instar).

- Rearing & Development: Rear all groups under otherwise identical conditions (temperature, light/dark cycle, ad libitum access to standardized diet) until they reach adulthood.

- Behavioral Assay: Upon reaching sexual maturity, isolate and record the courtship signals (e.g., pheromone production, wing vibration patterns) produced by males from each group in a standardized assay.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare courtship signals between Group A and Group B. A statistically significant difference indicates that rearing density affects courtship, evidence of developmental plasticity.

- Analyze Group C. If their courtship signals resemble those of the group they started in (A), it reinforces that the critical period for this plasticity has passed (developmental). If their signals resemble the group they were switched to (B), it suggests a more activational form of plasticity, where the current environment dominates.

Protocol 2: Probing Cortico-Striatal Plasticity Mechanisms

This protocol is based on research that bridges synaptic physiology and behavior to elucidate the mechanisms of operant learning, specifically the role of the striatum as the action-reinforcement interface [11].

- Slice Preparation & Electrophysiology: Prepare corticostriatal brain slices from rodent models. Use whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from identified D1- or D2-type Medium Spiny Neurons (MSNs) to stimulate cortical inputs.

- STDP and Dopamine Manipulation: Apply a Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity (STDP) protocol, precisely controlling the timing of pre- and post-synaptic spikes. Simultaneously, bath-apply different concentrations of dopamine (or D1/D2 receptor-specific agonists/antagonists) to mimic phasic reinforcement signals.

- Synaptic Weight Measurement: Measure changes in synaptic strength (EPSP amplitude) before and after the paired stimulation to map the conditions that induce Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) or Long-Term Depression (LTD). This builds a bottom-up, data-driven model of plasticity [11].

- Behavioral Correlation & Computational Modeling: Train rodents in an operant lever-pressing task. Use in vivo recordings or optogenetics to track the activity of D1 and D2 MSN populations during learning, extinction, and renewal phases. Finally, use a computational model to test whether the in vitro-derived plasticity rules can predict the observed in vivo neural activity changes and resulting behavior [11].

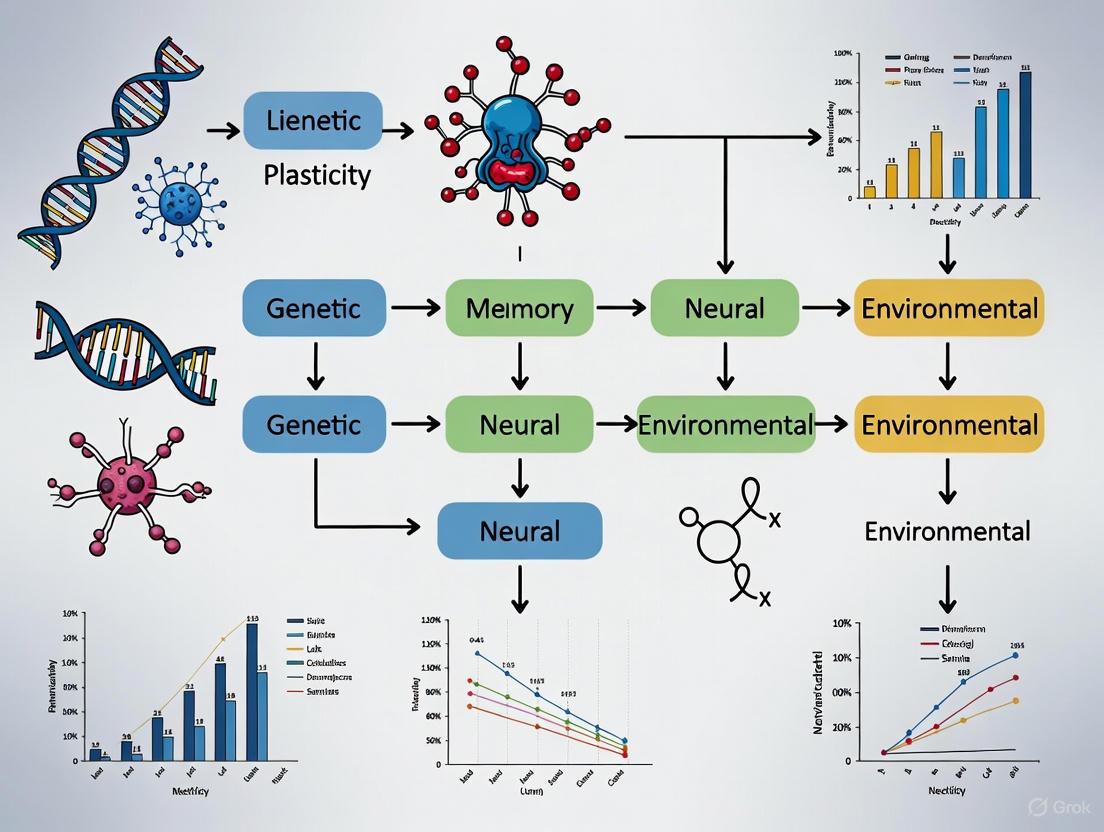

Diagram 1: A model of the three-factor interaction—spike timing, dopamine level, and dopamine receptor type—that determines the direction of synaptic plasticity (LTP vs. LTD) at cortico-striatal synapses, crucial for operant learning [11].

Neurobiological and Neurochemical Mechanisms

The classification of plasticity types is grounded in distinct, though sometimes overlapping, neurobiological substrates. Activational plasticity often involves rapid neurochemical modulation. For instance, the neuropeptides Opioids, Orexin, Neuropeptide Y (NPY), and Oxytocin have been shown to shape context-dependent feeding responses, allowing an organism to adjust its eating behavior based on energy state, time of day, or stressors [9]. These systems act on existing circuits to modulate behavioral output. Conversely, developmental plasticity involves more profound structural and functional changes in the brain, such as the formation of new neuronal pathways [1]. Learning-induced developmental plasticity is supported by mechanisms like long-term potentiation (LTP), dendritic spine remodeling, and adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus [1].

The basal ganglia, particularly the striatum, serve as a key neural interface where reinforcement signals (dopamine) interact with action representations (from cortex) to shape behavior through both types of plasticity [11]. Phasic dopamine, signaling a reward prediction error, gates complex, spike-timing-dependent plasticity at cortico-striatal synapses on D1- and D2-receptor expressing Medium Spiny Neurons (MSNs) [11]. This plasticity alters the future likelihood of selecting actions associated with positive outcomes. The opposing roles of the D1 (direct) and D2 (indirect) pathways—promoting action selection and suppression, respectively—are tuned by these experiences, providing a mechanistic basis for learning and extinction [11].

Diagram 2: A flowchart illustrating how different stimuli or experiences trigger either developmental or activational plasticity, engage distinct primary mechanisms, and lead to different behavioral outcomes.

Behavioral plasticity, defined as the change in an organism's behavior resulting from exposure to stimuli, represents a core adaptive capacity of the nervous system [1]. This plasticity manifests in two primary forms: developmental plasticity, which occurs over extended periods through gene-environment interactions, and contextual plasticity, which involves rapid behavioral adaptation to immediate environmental cues [1]. At the neurobiological level, these behavioral adaptations are orchestrated by a sophisticated molecular toolkit centered on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), synaptic proteins, and neural circuit dynamics. BDNF has emerged as a crucial regulator of synaptic development, plasticity, and cognitive function, serving as a molecular translator that converts neural activity into structural and functional changes in the brain [13] [14] [15]. This technical guide examines the core components of this neurobiological toolkit, detailing the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic applications relevant to researchers and drug development professionals investigating the fundamental basis of behavioral adaptation.

BDNF Signaling: Core Pathways and Molecular Regulation

BDNF Synthesis and Processing

BDNF undergoes a complex maturation process that yields functionally distinct isoforms with unique biological activities. The synthesis pathway involves several critical stages:

- Pre-pro-BDNF synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum following gene transcription [16] [17]. The initial pre-pro-BDNF precursor contains a signal peptide that directs it to the secretory pathway.

- Pro-BDNF conversion occurs in the Golgi apparatus where the signal peptide is cleaved, yielding the immature pro-BDNF form with a molecular weight of approximately 32 kDa [16] [17]. Glycosylation at residue N123 within the prodomain facilitates subsequent cleavage.

- Proteolytic cleavage to mature BDNF (~13 kDa) can occur intracellularly through furin and convertase 7 in the Golgi apparatus, or extracellularly via tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), plasmin, and matrix metalloproteinases [16].

- Secretion and signaling: Mature BDNF is secreted through interaction with the sortilin receptor and can be released from both axon terminals and dendrites, enabling bidirectional synaptic communication [16].

Table 1: BDNF Isoforms and Their Functional Characteristics

| Isoform | Molecular Weight | Receptor Preference | Primary Functions | Cellular Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pro-BDNF | ~27-30 kDa | N/A | Inactive precursor; intracellular trafficking | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| pro-BDNF | ~32 kDa | p75NTR/sortilin | Promotes apoptosis, synaptic pruning | Golgi apparatus, extracellular space |

| m-BDNF | ~13 kDa | TrkB | Enhances synaptic plasticity, cell survival | Secreted form, synaptic clefts |

Receptor Binding and Downstream Signaling

BDNF isoforms signal through two primary receptor systems that mediate opposing functional outcomes:

TrkB Receptor Signaling: Mature BDNF exhibits high affinity for the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), triggering dimerization and autophosphorylation that initiates several downstream cascades [17] [15]. Key pathways include:

- PI3K/Akt pathway: Promotes neuronal survival and growth through inhibition of apoptotic signals

- MAPK/ERK pathway: Regulates gene expression and protein synthesis crucial for long-term synaptic plasticity

- PLCγ pathway: Modulates intracellular calcium release and synaptic efficacy

p75NTR Signaling: pro-BDNF preferentially binds to the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), often in complex with sortilin, activating signaling cascades that promote apoptosis, synaptic pruning, and long-term depression [16] [15]. This opposing action to TrkB signaling creates a dynamic regulatory system that maintains neural circuit homeostasis.

The following diagram illustrates the BDNF synthesis pathway and receptor signaling:

Synaptic Proteins and Plasticity Mechanisms

Structural Components of the Synapse

The synaptic junction contains a sophisticated protein network that mediates structural and functional plasticity. Key components include:

- Presynaptic terminal proteins: Synapsin, synaptobrevin, and syntaxin regulate vesicle docking, priming, and neurotransmitter release probability. These proteins undergo activity-dependent phosphorylation that modulates synaptic efficacy.

- Postsynaptic density proteins: PSD-95, SHANK, and Homer form scaffold complexes that organize glutamate receptors, signaling molecules, and cytoskeletal elements. BDNF signaling directly modulates the expression and organization of these scaffolds.

- Cell adhesion molecules: Neuroligins, neurexins, and cadherins mediate trans-synaptic adhesion and bidirectional signaling, stabilizing synaptic connections during plasticity events.

Regulation of Synaptic Protein Expression by BDNF

BDNF signaling through TrkB receptors coordinates the synthesis and distribution of synaptic proteins through multiple mechanisms:

- Local translation: BDNF activates mTOR and MAPK pathways that enhance the local translation of synaptic proteins in dendrites, facilitating rapid synaptic remodeling independent of somatic gene transcription.

- Transcriptional regulation: BDNF-induced CREB phosphorylation increases the expression of genes encoding synaptic proteins, including synapsin I and PSD-95, creating a positive feedback loop that stabilizes synaptic strengthening.

- Proteolytic processing: Through regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and plasminogen activators, BDNF signaling controls the extracellular cleavage of pro-neurotrophins and cell adhesion molecules, modulating synaptic structural integrity.

Table 2: Key Synaptic Proteins Regulated by BDNF Signaling

| Protein | Synaptic Location | Function | Regulation by BDNF |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSD-95 | Postsynaptic density | Scaffold protein for glutamate receptors | Increased transcription and dendritic translation |

| Synapsin I | Presynaptic terminal | Regulates synaptic vesicle mobilization | Phosphorylation via MAPK/ERK pathway |

| SHANK | Postsynaptic density | Master scaffold protein; links receptors to cytoskeleton | Enhanced expression through CREB signaling |

| Neuromodulin | Presynaptic terminal | Regulates presynaptic calcium and neurotransmitter release | Phosphorylation via PKC pathway |

| AMPA Receptors | Postsynaptic membrane | Mediates fast excitatory synaptic transmission | Increased surface expression and trafficking |

Neural Circuit Dynamics and Systems-Level Plasticity

Hippocampal Circuitry and Spatial Memory

The hippocampus serves as a prime model for studying BDNF-dependent circuit plasticity. Anatomically segmented into dorsal (spatial memory) and ventral (emotional responses) subregions, the hippocampus contains the trisynaptic circuit (dentate gyrus → CA3 → CA1) that undergoes experience-dependent modification [16]. BDNF modulates synaptic strength at multiple points in this circuit:

- Dentate Gyrus: BDNF promotes adult neurogenesis and integration of new granule cells into existing circuits, a process crucial for pattern separation.

- CA3-CA1 Synapses: BDNF regulates long-term potentiation (LTP) through TrkB-mediated enhancement of NMDA receptor function and AMPA receptor trafficking.

- Temporal Dynamics: The timing of BDNF release critically determines its effects on circuit plasticity, with precise temporal patterns required for LTP induction and stabilization [14].

Prefrontal Circuits and Executive Function

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) exhibits distinctive BDNF-dependent plasticity mechanisms that underlie cognitive flexibility and working memory:

- Dopamine-BDNF interactions: Mesocortical dopamine projections modulate BDNF expression in the PFC, creating a regulatory loop that gates cognitive flexibility.

- Stress vulnerability: PFC circuits are particularly sensitive to stress-induced BDNF downregulation, which impairs executive function and promotes maladaptive behavioral responses.

- Critical period plasticity: BDNF expression regulates the opening and closing of developmental critical periods in PFC circuits, influencing the capacity for adult cognitive plasticity.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for studying BDNF in neural circuits:

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Assessing BDNF Expression and Signaling

Protocol: BDNF Measurement in Rodent Hippocampus Following Dietary and Exercise Interventions

- Animal Models: Male C57BL/6 mice (4 weeks old) are randomly assigned to control diet (normal fat) or high-fat diet (HFD: 60% fat) groups for 8-12 weeks to induce metabolic and cognitive alterations [16].

- Exercise Intervention: Following diet induction, HFD animals are subdivided into sedentary, low-intensity training (LIT: 30min/day, 10m/min), and high-intensity training (HIT: 60min/day, 15m/min) groups. Training is conducted 5 days/week for 8 weeks using motorized treadmills [16].

- Tissue Collection: Animals are euthanized 24-48 hours after final exercise session. Hippocampi are rapidly dissected and divided for protein, RNA, and morphological analyses.

- BDNF Quantification:

- ELISA: Homogenize hippocampal tissue in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Use commercial BDNF ELISA kits with sensitivity threshold <5pg/mL. Perform measurements in duplicate with appropriate standard curves.

- Western Blot: Separate proteins (20-40μg) via SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membranes, and probe with anti-BDNF antibodies (distinguishing pro- and mature BDNF forms). Normalize to β-actin or GAPDH loading controls.

- qRT-PCR: Extract total RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform quantitative PCR with BDNF exon-specific primers to assess transcript variants.

Synaptic Protein Analysis

Protocol: Assessment of Synaptic Protein Composition Following BDNF Manipulation

- Synaptosome Preparation: Isolate synaptosomes from hippocampal or cortical tissue using discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation (0.8M/1.2M sucrose interfaces).

- Postsynaptic Density (PSD) Fractionation: Further fractionate synaptosomes using Triton X-100 extraction to isolate PSD-enriched fractions.

- Multiplex Immunoblotting: Probe PSD fractions with antibodies against key synaptic proteins (PSD-95, SHANK, GluA1, GluN2B, SynGAP). Use fluorescent secondary antibodies for simultaneous detection and quantification.

- Morphological Analysis: Perform immunohistochemistry on free-floating brain sections (40μm) using antibodies against synaptic markers followed by confocal microscopy and dendritic spine quantification.

Behavioral Assessment of Plasticity

Protocol: Spatial Memory Evaluation Using Y-Maze Testing

- Apparatus: The Y-maze consists of three identical arms (40cm long × 10cm wide × 15cm high) positioned at 120° angles with distinct spatial cues on surrounding walls [16].

- Testing Protocol: Habituate animals to the maze for 5 minutes 24 hours before testing. During testing, place the mouse at the end of one designated start arm and allow free exploration for 8 minutes. Record all arm entries manually or with automated tracking software.

- Analysis: Calculate spontaneous alternation percentage as the number of triads containing entries into all three arms divided by the maximum possible alternations (total arm entries - 2) × 100. Compare between experimental groups using appropriate statistical tests (ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons).

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for BDNF and Synaptic Plasticity Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF Modulators | Recombinant BDNF, BDNF monoclonal antibodies, TrkB agonists (7,8-DHF), TrkB antagonists (ANA-12) | Experimental manipulation of BDNF signaling in vitro and in vivo | Consider blood-brain barrier permeability for in vivo studies; monitor dose-dependent effects |

| Synaptic Protein Antibodies | Anti-PSD-95, Anti-Synapsin I, Anti-SHANK, Anti-GluA1, Anti-GluN2B | Protein quantification, cellular localization, immunohistochemistry | Validate specificity using knockout controls; optimize for specific applications (WB, IHC, IP) |

| Gene Expression Tools | BDNF promoter-reporter constructs, BDNF shRNA vectors, CRISPR-Cas9 systems for BDNF editing | Gene regulation studies, pathway analysis, functional screening | Account for multiple BDNF transcripts; consider temporal control of gene manipulation |

| Animal Models | BDNF heterozygous knockout mice, Val66Met knock-in mice, CRE-lox systems for region-specific deletion | Study of BDNF in specific brain regions, developmental stages, or behavioral paradigms | Monitor compensatory mechanisms; consider developmental versus acute manipulations |

| Activity Reporters | AAV-BDNF promoter-GCaMP, AAV-BDNF promoter-cFos-tTA | Monitoring BDNF promoter activity in live tissue or specific neuronal populations | Optimize viral titers; confirm specificity with control constructs |

Therapeutic Applications and Research Translation

BDNF in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

BDNF dysregulation has been implicated in numerous neuropsychiatric conditions, making it a promising therapeutic target:

- Major Depressive Disorder: Meta-analyses confirm that people with MDD have significantly lower peripheral and central BDNF levels compared to non-depressed individuals [18]. A negative correlation exists between blood BDNF levels and symptom severity, while successful antidepressant treatment increases BDNF levels proportional to clinical improvement.

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer's disease is characterized by reduced BDNF expression in critical brain regions, contributing to synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline [15]. BDNF-based therapeutic strategies aim to enhance neuronal survival and counteract disease pathology.

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Altered BDNF signaling during critical developmental windows has been associated with autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, highlighting its importance in proper circuit formation [17] [15].

Challenges in BDNF-Targeted Therapeutics

Despite promising preclinical findings, translating BDNF research into effective clinical interventions faces several challenges:

- Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrance: BDNF is a large, charged molecule with poor blood-brain barrier permeability, requiring innovative delivery strategies such as intranasal administration or viral vector systems [15].

- Signaling Specificity: The pleiotropic nature of BDNF signaling and opposing actions of proBDNF/p75NTR and mBDNF/TrkB pathways complicates therapeutic targeting without unintended consequences.

- Biomarker Limitations: Peripheral BDNF measurements show mixed reliability as biomarkers of central BDNF activity, as evidenced by null findings in psychoplastogen studies where peripheral BDNF failed to reflect expected CNS plasticity changes [19].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Innovative approaches are advancing BDNF research and therapeutic development:

- Nanoparticle Delivery Systems: Lipid nanoparticle-based mRNA therapies show promise for targeted BDNF expression in specific brain regions while overcoming blood-brain barrier limitations [15].

- CRISPR-dCas9 Epigenetic Editing: Precise modulation of BDNF expression through epigenetic editing of specific promoters offers temporal and spatial control not achievable with traditional approaches [15].

- Humanized Model Systems: iPSC-derived neurons and cerebral organoids provide platforms for studying BDNF in human genetic backgrounds and testing patient-specific therapeutic responses [15].

- Multiplex Biomarker Panels: Combining BDNF measurements with additional biomarkers (tau, amyloid-β, inflammatory markers) improves diagnostic and prognostic specificity for neurodegenerative disorders [15].

The neurobiological toolkit centered on BDNF, synaptic proteins, and neural circuits provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the mechanisms underlying behavioral plasticity. BDNF serves as a critical mediator that translates neural activity into structural and functional changes at synapses, coordinating circuit-level adaptations that enable cognitive and behavioral flexibility. The experimental methodologies and research reagents detailed in this guide represent essential resources for investigating these complex processes. While significant progress has been made in deciphering BDNF's roles in health and disease, translating this knowledge into effective therapeutics requires continued innovation in delivery systems, biomarker development, and patient stratification strategies. Future research integrating advanced technologies with rigorous experimental approaches will further elucidate how this molecular toolkit shapes behavioral adaptation and cognitive function across the lifespan.

The capacity of an organism to adapt its behavior in response to changing internal states and environmental conditions represents a fundamental aspect of behavioral plasticity. This adaptive capability relies on sophisticated neural mechanisms that integrate endogenous triggers (internal physiological signals) with contextual cues (external sensory information) to guide appropriate behavioral responses. Understanding these integrative processes has become particularly crucial in biomedical fields, where researchers are developing advanced therapeutic platforms that respond to specific biological triggers.

This whitepaper examines the neurobiological principles governing how internal and external cues are integrated to modulate behavior, with specific emphasis on applications in drug development and therapeutic interventions. We explore the mechanistic basis of cue integration across multiple scales, from molecular signaling pathways to neural circuit operations, providing experimental frameworks and technical resources for researchers investigating behavioral plasticity.

Theoretical Foundations of Cue Integration

Defining Endogenous and Contextual Triggers

Endogenous triggers encompass internal physiological signals that originate from within an organism, including metabolic states, hormonal fluctuations, immune responses, and other homeostatic processes. In therapeutic contexts, these may include specific pH gradients, redox potential variations, enzyme concentrations, or disease-specific biomarkers that can trigger targeted drug release or activity [20].

Contextual cues comprise external sensory information derived from the environment, including visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory stimuli that provide spatial, temporal, and social context for behavior. In neuroscience research, these may include controlled sensory inputs such as visual landmarks, auditory signals, or other experimentally manipulated environmental features [21].

The integration of these trigger types occurs through specialized neural circuits that weigh the reliability and salience of each cue source to generate unified perceptual estimates and behavioral responses. This integration process follows mathematically definable principles that optimize behavioral outcomes based on probabilistic reasoning [22].

Neural Mechanisms of Cue Integration

The head direction (HD) system exemplifies how neural circuits integrate multimodal cues. Functioning as a ring attractor network, this system maintains a persistent "activity bump" representing current heading direction, updated through continuous integration of self-motion cues (endogenous) and environmental sensory inputs (contextual) [21].

Research in Drosophila reveals that cue salience and familiarity directly impact the precision of HD encoding. More informative cues produce narrower activity bumps and higher amplitude neural responses, indicating enhanced encoding accuracy. During cue conflicts, the neural system prioritizes more reliable cues, demonstrating adaptive weighting mechanisms [21].

The synaptic weights between sensory input neurons and HD cells exhibit experience-dependent plasticity, following Hebbian learning rules where co-active sensory and HD neurons strengthen their connections. This plasticity mechanism allows the system to continuously update cue validity based on experience, allocating greater weight to familiar, stable cues [21].

Table 1: Neural Response Properties to Varying Cue Conditions

| Cue Condition | Bump Width | Bump Amplitude | HD Encoding Accuracy | Attractor Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cue | Wide | Low | Low | Low |

| Dim cue | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Moderate |

| Bright cue | Narrow | High | High | High |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Neurophysiological Investigation of Cue Integration

The following experimental protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for investigating how neural systems integrate internal and external cues, based on established methodologies in systems neuroscience [21]:

Subject Preparation and Apparatus

- Express calcium indicators (e.g., jGCaMP7f) in target HD neurons (e.g., EPG neurons) under Gal4-UAS control

- Secure subjects (e.g., Drosophila) in a head-fixed configuration while allowing locomotion on a spherical treadmill

- Implement a virtual reality environment capable of presenting controlled visual cues with adjustable intensity and position

- Use a two-photon microscope for population calcium imaging of neural activity

Stimulus Presentation and Data Collection

- Present visual cues of varying intensities (no cue, dim cue, bright cue) in randomized, interleaved 200-second blocks

- Record rotational velocity of the spherical treadmill to infer intended rotational velocity

- Rotate direction cues in closed loop with ball rotation to maintain consistent cue positioning relative to heading

- Collect neural population activity data synchronized with behavioral measurements and stimulus presentations

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate HD encoding accuracy as 1 - circular variance in the offset between HD and bump position

- Measure bump width and amplitude across different cue conditions

- Analyze behavioral orientation consistency in virtual space

- Correlate individual differences in bump dynamics with HD encoding accuracy

This experimental paradigm has demonstrated that increasing cue intensity systematically improves HD encoding accuracy while producing narrower and higher amplitude activity bumps in the HD network [21].

Therapeutic Development for Trigger-Responsive Drug Delivery

The following protocol provides a methodology for developing and testing stimulus-responsive drug delivery systems (DDS) that activate in response to specific endogenous or external triggers [20]:

Material Selection and Synthesis

- Select stimulus-responsive polymers based on target trigger (pH-sensitive, redox-sensitive, etc.)

- Synthesize block copolymers with cleavable linkages (disulfide bonds for redox sensitivity, hydrazone bonds for pH sensitivity)

- Formulate nanoparticles using appropriate methods (nanoprecipitation, emulsion-solvent evaporation, etc.)

- Characterize physicochemical properties (size, zeta potential, drug loading efficiency)

Trigger-Responsive Evaluation

- Incubate DDS under conditions mimicking physiological versus pathological environments

- For redox-responsive systems: Evaluate drug release in presence of glutathione at intracellular (10 mM) versus extracellular (2-20 μM) concentrations

- For pH-responsive systems: Test drug release across pH gradients (pH 7.4 for physiological, pH 5.0-6.5 for tumor microenvironments or endolysosomal compartments)

- For externally activated systems: Apply appropriate triggers (light, magnetic field, ultrasound) and measure release kinetics

Biological Assessment

- Evaluate cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking in relevant cell models

- Assess cytotoxicity and therapeutic efficacy compared to non-responsive controls

- For in vivo studies: Analyze biodistribution, target site accumulation, and trigger-responsive activation

- Compare therapeutic outcomes between stimulus-responsive and conventional formulations

This approach has demonstrated successful development of DDS that maintain stability during circulation while rapidly releasing therapeutic payload upon encountering specific triggers at target sites [20].

Signaling Pathways and Neural Circuits

The integration of endogenous and contextual cues occurs through specialized neural pathways and molecular mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the core architecture of the head direction circuit and its trigger integration mechanisms:

Head Direction Circuit and Trigger Integration Mechanisms

The molecular implementation of trigger-responsive systems employs specialized materials and mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates stimulus-responsive drug release mechanisms:

Stimulus-Responsive Drug Release Mechanisms

Quantitative Analysis of Cue Integration

Research across multiple domains has quantified how endogenous and contextual triggers influence biological systems. The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships in cue integration and trigger-responsive systems.

Table 2: Quantitative Properties of Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems [20]

| Trigger Type | Specific Stimulus | Response Mechanism | Release Kinetics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous: Redox | Glutathione (2-20 μM extracellular vs. 10 mM intracellular) | Disulfide bond cleavage | Rapid release (minutes) | Intracellular drug delivery, gene delivery |

| Endogenous: pH | pH 7.4 (physiological) vs. pH 5.0-6.5 (tumor/endosomal) | Acid-labile bond hydrolysis | Sustained release (hours) | Tumor targeting, endosomal escape |

| Endogenous: Enzyme | Overexpressed enzymes (e.g., MMPs, phosphatases) | Enzyme-specific substrate cleavage | Variable (enzyme-dependent) | Disease-specific targeting |

| Exogenous: Light | Specific wavelengths (UV, NIR) | Photochemical reactions | Precise temporal control | Spatiotemporally controlled release |

| Exogenous: Magnetic | Alternating magnetic fields | Magnetic hyperthermia | On-demand pulsatile release | Deep tissue targeting |

| Exogenous: Ultrasound | Specific frequencies/intensities | Cavitation, thermal effects | Tunable release profiles | Non-invasive deep tissue penetration |

Table 3: Neural Encoding Properties Under Different Cue Conditions [21]

| Cue Parameter | Measurement Method | Effect on HD Encoding | Underlying Mechanism | Behavioral Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cue intensity (brightness) | Manipulated in interleaved blocks | Higher accuracy with increased intensity | Enhanced signal-to-noise ratio in sensory input | More consistent orientation in virtual space |

| Cue reliability (signal-to-noise) | Conflict paradigms between cues | More reliable cues weighted more heavily | Experience-dependent synaptic plasticity | Adaptive reorientation to stable cues |

| Cue familiarity | Extended exposure to stable cues | Increased weighting of familiar cues | Hebbian strengthening of sensory→HD connections | Faster orientation responses |

| Multiple congruent cues | Presentation of complementary cues | Superadditive improvement in encoding accuracy | Integration across sensory modalities | Enhanced navigation precision |

| Cue conflict | Experimental mismatch between cues | Rapid recalibration of cue weights | Plasticity in sensory synaptic inputs | Behavioral adjustment to cue reliability |

The following table compiles essential research reagents and methodologies for investigating endogenous and contextual trigger integration:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Trigger Integration Studies

| Reagent/Method | Technical Function | Research Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| jGCaMP7f calcium indicator | Neural activity monitoring via calcium imaging | Real-time recording of HD cell population dynamics | Expression in EPG neurons under Gal4-UAS control [21] |

| Redox-sensitive copolymers | Disulfide-linked block copolymers | Intracellular drug delivery responsive to glutathione | PEG-disulfide-PPS formation of shell-sheddable micelles [20] |

| Virtual reality environments | Controlled sensory cue presentation | Investigation of visual cue integration in navigation | Closed-loop cue rotation synchronized with spherical treadmill [21] |

| pH-responsive nanomaterials | Acid-labile polymer conjugates | Targeted drug release in tumor microenvironments | Acetal/ hydrazone bonds cleaved at endolysosomal pH [20] |

| Two-photon microscopy | High-resolution neural population imaging | Simultaneous monitoring of entire HD cell ensembles | Population calcium imaging at cellular resolution [21] |

| Layer-by-layer (LbL) capsules | Redox-responsive drug carriers | Plasmid DNA and drug delivery with triggered release | PVPON/PMAA capsules with disulfide cross-linkers [20] |

| Motion capture systems (VICON) | Kinematic movement analysis | Quantitative assessment of movement patterns | Upper-body modeling with Plug-in-Gait marker placement [23] |

| Wireless EMG systems (Delsys) | Muscle activity monitoring | Electrophysiological correlation with cue-directed movement | SENIAM-guided electrode placement on target muscles [23] |

The integration of endogenous and contextual triggers represents a fundamental mechanism underlying behavioral plasticity, with far-reaching implications for basic neuroscience and therapeutic development. The neural circuits governing these processes employ sophisticated weighting mechanisms that dynamically adjust based on cue reliability, salience, and familiarity, implemented through experience-dependent synaptic plasticity.

The experimental approaches and technical resources outlined in this whitepaper provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for investigating these integrative processes across multiple biological scales. Furthermore, the growing understanding of how biological systems naturally integrate internal and external cues has inspired innovative therapeutic strategies, particularly in targeted drug delivery systems that respond to specific pathological triggers.

Future research in this domain will likely focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying cue weighting plasticity, developing more precise spatiotemporal control over trigger-responsive therapeutic systems, and exploring how disruptions in cue integration mechanisms contribute to neurological and psychiatric disorders. The continued convergence of neuroscience, materials science, and drug development in this area promises to yield increasingly sophisticated approaches for modulating behavior and treating disease through targeted engagement of endogenous and contextual triggers.

Research Methods and Translational Applications in Drug Development

Behavioral plasticity, defined as the change in an organism's behavior resulting from exposure to stimuli such as changing environmental conditions, represents a critical interface between neural mechanisms and observable behavioral outputs [1]. This phenomenon encompasses two primary types: developmental plasticity, which refers to gene-environment interactions affecting phenotype, and activational plasticity, which involves innate physiological processes that can involve structural changes in the body [9]. The study of behavioral plasticity provides a foundational framework for translating basic neurobiological research into clinical applications, particularly in neuropsychiatric drug development. Model organisms like C. elegans offer simplified yet powerful experimental systems for elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of behavioral plasticity, while clinical trials extend these findings to human therapeutic contexts, creating a continuum of discovery from laboratory to clinic.

The nematode C. elegans serves as an exceptional model for studying behavioral plasticity due to its simple nervous system of 302 neurons, thoroughly characterized connectome, genetic tractability, and isogenic background [24]. Research in this organism has identified numerous paradigms of behavioral plasticity, including learning, memory, and adaptive feeding responses, which are modulated by evolutionarily conserved neuropeptides and signaling pathways [24] [9]. These conserved mechanisms enable researchers to bridge the conceptual and experimental gap between invertebrate models and mammalian systems, ultimately informing drug discovery processes for cognitive, neurodevelopmental, and neuropsychiatric disorders in humans.

Experimental Paradigms in C. elegans

Fundamental Behavioral Plasticity Assays

C. elegans research employs several well-established behavioral paradigms to quantify plasticity mechanisms. These assays measure how the nematode's behavior changes in response to specific environmental cues, experiences, or pharmacological manipulations [24]. Key paradigms include thermotaxis, where worms learn to associate specific temperatures with food availability; chemotaxis learning, where animals modify their attraction to chemical cues based on past experience; and mechanosensory habituation, where worms decrease their response to repeated gentle touch stimuli [24]. These behavioral paradigms provide quantifiable metrics for investigating the genetic, molecular, and circuit-level mechanisms underlying behavioral adaptation.

The experimental workflow for these paradigms typically involves exposing animals to controlled stimuli while recording their behavioral responses using automated tracking systems. For example, in learning and memory assays, worms might be conditioned to associate a neutral odor with the presence or absence of food, followed by testing their preference for that odor in a choice chamber. The change in behavioral response between pre- and post-conditioning phases serves as a quantitative measure of learning and memory formation [24]. These assays generate rich datasets on parameters such as response latency, locomotion patterns, turning frequency, and attraction/avoidance behaviors, which can be statistically analyzed to draw inferences about underlying plasticity mechanisms.

Pharmacological Interventions and Methodologies

Rigorous pharmacological experimentation in C. elegans requires standardized protocols for compound administration to ensure reproducible results in behavioral studies. Research rigor is significantly enhanced by pairing genetic tools with pharmacology and manipulations of solutes or ions [25]. Treatment methodologies must account for compound stability, solubility, and potential degradation to maintain consistent exposure concentrations throughout experiments.

Table 1: Pharmacological Treatment Methods in C. elegans Research

| Method | Protocol Details | Best Use Cases | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agar Plate Supplementation | Compounds added to NGM agar before pouring plates; requires adjustment of ddH2O volume to account for added liquids [25] | Stable compounds; long-term exposure studies; behavioral assays conducted on solid media | Ensure sterility; fresh plates recommended for each experiment; adjust osmolarity if necessary |

| Post-Polymerization Application | Compounds applied directly to surface of polymerized agar plates; allowed to diffuse through medium [25] | Compounds sensitive to agar heating; rapid screening of multiple conditions | Uneven diffusion may create concentration gradients; use consistent drying times |

| Liquid Culture Exposure | Animals incubated in liquid media containing pharmacological agents with food source [25] | High-throughput applications; precise concentration control; imaging experiments | Monitor oxygen levels; potential for altered behavior in liquid environment |

| Acute vs. Chronic Dosing | Varying exposure duration from minutes (acute) to entire development (chronic) [25] | Distinguishing rapid vs. adaptive responses; developmental plasticity studies | Compound stability crucial for chronic exposures; prepare fresh solutions as needed |

Standardized preparation of materials is essential for pharmacological experiments. Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) plates are prepared with 2.5g bacto peptone, 3g NaCl, 17g agar, 0.2g streptomycin, and 975mL ddH2O, autoclaved using liquid program (120°C for 20 minutes) [25]. After cooling to 55°C, supplements are added: 1mL each of 1M CaCl₂, 1M MgSO₄, 5mg/mL cholesterol, and 10mg/mL nystatin, plus 25mL of 0.5M KP buffer [25]. For compound delivery, stock solutions are prepared in appropriate solvents (ddH2O, DMSO, or chloroform) based on solubility, with aqueous solutions filtered through 0.22μm pores for sterility [25]. Critical considerations include verifying compound stability (using fresh serotonin each time, for example), storing light-sensitive compounds in darkness, and maintaining sterility during all procedures [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Behavioral Data

Behavioral data from C. elegans experiments require appropriate statistical approaches to draw meaningful conclusions about plasticity mechanisms. Quantitative analysis ranges from simple descriptive statistics to multivariate inferential approaches, depending on the experimental design and research questions.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis Methods for C. elegans Behavioral Data

| Analysis Type | Appropriate Statistical Tests | Application in Behavioral Plasticity Research | Presentation Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Descriptive statistics (range, mean, median, mode, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis) [26] | Characterizing single behavioral parameters (e.g., locomotion speed, turning frequency) | Graphs (line graphs, histograms); charts (pie charts, descriptive tables) [26] |

| Univariate Inferential Analysis | T-test, chi-square [26] | Comparing two experimental groups (e.g., wildtype vs. mutant; drug vs. control) | Summary tables of test results; contingency tables [26] |

| Bivariate Analysis | T-tests, ANOVA, Chi-square [26] | Examining relationships between two variables (e.g., dose-response curves; genotype × treatment interactions) | Summary tables; contingency tables [26] |

| Multivariate Analysis | ANOVA, MANOVA, Chi-square, correlation, regression (binary, multiple, logistic) [26] | Analyzing complex interactions (e.g., multiple genes × multiple environments × behavioral outcomes) | Summary tables [26] |

Experimental design must account for potential confounding factors in behavioral assays, including animal developmental stage, nutritional status, time of day, and previous experience. Well-controlled studies use synchronized worm populations obtained through bleaching protocols, where gravid adults are collected, washed, and resuspended in hypochlorite solution (20.4mM NaOCl and 8.2mM NaOH) to dissolve cuticles and isolate eggs [25]. These eggs are then seeded onto plates at standardized densities (120-150 eggs per plate) to prevent overcrowding and starvation, ensuring consistent growth conditions across experimental groups [25].

Neurobiological Mechanisms of Behavioral Plasticity

Molecular Mediators

At the molecular level, behavioral plasticity is regulated by conserved neuropeptide systems that modulate neural circuit function. Key neuropeptides including opioids, orexin, neuropeptide Y (NPY), and oxytocin have been demonstrated to shape feeding responses and other plastic behaviors across species [9]. These signaling molecules act through specific G-protein coupled receptors to modulate neuronal excitability, synaptic strength, and circuit dynamics, thereby altering behavioral outputs based on internal state and external cues.

In C. elegans, forward genetic analyses have identified numerous genes involved in behavioral plasticity, including those encoding neuropeptides, their receptors, and downstream signaling components [24]. Reverse genetic approaches and genomic technologies have complemented these discoveries by enabling targeted investigation of candidate genes predicted to play roles in neural plasticity [24]. The conservation of these molecular pathways between nematodes and mammals provides a foundation for translating discoveries from model systems to clinical applications, particularly for neuropsychiatric disorders involving disrupted motivational states, reward processing, or stress responses.

Neural Circuit Mechanisms

The neurobiological basis of behavioral plasticity involves coordinated changes across multiple neural systems. Three primary processes underlie this phenomenon: (1) neural plasticity mechanisms that enable rapid changes in circuit function; (2) neuromodulatory systems that integrate and process stimuli; and (3) specialized brain regions that modulate specific behavioral domains [1]. Key mechanisms include long-term potentiation (LTP) that strengthens synaptic connections, dendritic spine remodeling that structurally reorganizes neural circuits, and adult neurogenesis in specific regions like the hippocampus that supports pattern separation and memory formation [1].

These neural plasticity mechanisms are regulated by neurochemical systems including dopamine-mediated reward learning, serotonin-modulated social and stress-related plasticity, and cortisol-mediated stress responses that promote behavioral flexibility [1]. At the molecular level, gene expression changes and epigenetic regulation mediated by transcription factors like CREB and neurotrophins like BDNF underlie experience-dependent plasticity that persists over time [1]. These mechanisms are implemented in specialized brain regions including the prefrontal cortex (executive control, behavioral flexibility), amygdala (emotionally driven learning), hippocampus (contextual learning and memory), and basal ganglia (habit formation and motor learning) [1].

Figure 1: Neurobiological Framework of Behavioral Plasticity. This diagram illustrates the integrated neural systems that mediate behavioral plasticity, from initial stimulus processing to behavioral output, highlighting key mechanisms, neurochemical systems, and specialized brain regions.

Translational Applications: From Model Organisms to Clinical Trials

Bridging Mechanisms from C. elegans to Mammals

The translation of behavioral plasticity research from model organisms to clinical applications leverages evolutionarily conserved mechanisms discovered in simplified systems. C. elegans studies have identified fundamental principles of behavioral plasticity that operate similarly in mammalian systems, including the roles of neuropeptide signaling, neuromodulation, and experience-dependent circuit reorganization [24] [9]. For example, research on feeding behavior plasticity in nematodes has revealed how neuropeptide systems including opioids, NPY, and orexin integrate internal metabolic state with external food cues to modulate foraging behavior - mechanisms with direct relevance to understanding eating disorders and obesity in humans [9].

The experimental approaches used in C. elegans research also provide methodological frameworks for clinical translation. High-throughput screening of pharmacological compounds in worms can identify candidate therapeutics that modulate specific plasticity mechanisms, which can then be evaluated in mammalian models and eventually human trials [25]. Similarly, genetic analyses in nematodes can identify conserved genes and pathways that may represent novel therapeutic targets for neuropsychiatric disorders. This translational pipeline enables efficient triaging of potential interventions before committing to resource-intensive clinical studies.

Clinical Trial Design for Behavioral Plasticity Interventions

Clinical trials targeting behavioral plasticity mechanisms require specialized design considerations to effectively capture plasticity-related outcomes. These trials typically investigate interventions for neuropsychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, and substance use disorders, where impaired behavioral plasticity constitutes a core feature of the pathology. Successful trial design incorporates appropriate endpoints that directly measure plasticity mechanisms rather than relying solely on traditional symptom rating scales.

Table 3: Clinical Trial Measures for Assessing Behavioral Plasticity

| Domain | Specific Measures | Clinical Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Flexibility | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Intra-Extra Dimensional Set Shift | Schizophrenia, OCD, prefrontal disorders | Requires specialized administration; sensitive to practice effects |

| Fear Extinction/Learning | Fear Potentiated Startle, Avoidance Learning Tasks | Anxiety disorders, PTSD | May induce temporary distress; requires careful ethical review |

| Reward Learning | Probabilistic Reward Task, Reinforcement Learning Paradigms | Depression, substance use disorders | Computational modeling enhances precision; subject to motivational confounds |

| Social Learning | Trust Game, Social Evaluation Tasks | Autism spectrum disorder, social anxiety | Ecological validity varies across tasks; culturally dependent |

| Neurophysiological Biomarkers | EEG (MMN, P300), fMRI (task-based connectivity), TMS (cortical plasticity) | Cross-diagnostic applications | Expensive; requires specialized equipment; provides mechanistic insight |

Clinical trials must also account for individual differences in behavioral plasticity, as genetic, developmental, and environmental factors create substantial variability in treatment responses [1]. Modern trial designs often incorporate precision medicine approaches that stratify participants based on biomarkers of plasticity, such as genetic variants in neuroplasticity-related genes (e.g., BDNF Val66Met), neurophysiological measures of cortical plasticity, or behavioral assays of learning capacity. This stratification enables targeted testing of interventions in patient subgroups most likely to benefit based on their specific plasticity profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Figure 2: Translational Research Workflow. This diagram outlines the experimental workflow from C. elegans discovery research through mammalian validation to human clinical application, highlighting essential tools and methodologies at each stage.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Behavioral Plasticity Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | C. elegans (N2 wildtype), transgenic rodent lines (e.g., BDNF knockout mice) | Provide experimentally tractable systems for mechanistic studies | Standardize genetic background; control for microbiota effects; maintain consistent housing conditions |