Behavioral Reaction Norm Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to behavioral reaction norm (BRN) analysis, a powerful framework that integrates individual consistency (personality) and environmental plasticity into a single quantitative trait.

Behavioral Reaction Norm Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to behavioral reaction norm (BRN) analysis, a powerful framework that integrates individual consistency (personality) and environmental plasticity into a single quantitative trait. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational concepts of BRNs, detailing how they decompose behavioral variation into intercepts (average behavior), slopes (plasticity), and residuals (predictability). We present cutting-edge methodological approaches, including random regression and Bayesian multilevel models, for estimating these parameters in complex datasets. The guide addresses common analytical challenges such as low statistical power and cross-experiment comparability, offering solutions like behavioral flow analysis and machine learning-based cluster stabilization. Finally, we cover validation strategies and comparative analyses, demonstrating BRN applications in predicting drug efficacy, individual treatment response, and optimizing risk minimization strategies in clinical settings.

Beyond Average Behavior: Foundational Principles of Behavioral Reaction Norms

Conceptual Foundation of Behavioral Reaction Norms

Core Definition and Theoretical Framework

A behavioral reaction norm (BRN) represents the spectrum of phenotypic variation produced when individuals are exposed to varying environmental conditions, describing how labile phenotypes vary as a function of organisms' expected trait values and plasticity across environments [1]. In essence, a BRN is the relationship describing the behavioral response of an individual over an environmental gradient, which becomes the trait of interest for evolutionary analysis [2]. This framework integrates two fundamental components: personality (consistent individual differences in behavior across time and contexts) and plasticity (within-individual variability in response to environmental changes) [2].

The BRN approach quantitatively frames individual-specific patterns through distinct but potentially integrated parameters: intercepts (expected phenotype in the average environment), slopes (expected change in phenotype in response to environmental variation), and within-individual residuals (magnitude of stochastic variability within a given environment) [1]. This perspective resolves historical debates by demonstrating that reaction norm parameters can be direct targets of natural selection, leading to differential patterns of adaptation in changing environments [1].

Historical Context and Evolutionary Significance

The reaction norm concept originated with Woltereck in 1909 and has become foundational in biological sciences [3]. Contemporary evolutionary frameworks emphasize that reaction norm parameters and their underlying mechanisms serve as putative targets of selection, with distinct consequences for evolutionary responses [1]. The "differential susceptibility" hypothesis articulates this perspective, suggesting that certain genotypes show heightened plasticity to environmental influences, resulting in both worse outcomes in adverse conditions and better outcomes in favorable conditions [3].

When study phenotypes mirror reproductive fitness, a non-trivial consequence of disordinal G×E (crossing reaction norms) is to preserve genotypic variation, since the relative fitness of competing genotypes differs across environments—sometimes favoring one genotype, sometimes another [3]. This theoretical framework creates bridges between behavioral genetics and longstanding streams of biological science [3].

Table 1: Key Parameters of Behavioral Reaction Norm Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Biological Interpretation | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RN Intercept | μ₀, μ₀j | Expected phenotype in the average environment | Represents average behavioral expression; subject to directional selection |

| RN Slope | βₓ, βₓj | Expected phenotypic change per unit environmental change | Quantifies plasticity; subject to selection in variable environments |

| RN Residual | σ₀, σ₀j | Magnitude of stochastic variability within an environment | Inverse of behavioral predictability; may reflect environmental sensitivity |

| Population Mean | μ₀, βₓ | Average intercept and slope across population | Characterizes species- or population-level adaptation |

| Individual Deviation | μ₀j, βₓj | Individual's deviation from population mean | Represents heritable variation available for selection |

Quantitative Framework and Analytical Methods

Statistical Estimation of Reaction Norm Parameters

Behavioral reaction norms are typically estimated using multilevel, mixed-effects models (specifically random regression) that quantify interindividual variation in reaction norm elevations and slopes, and the correlation between elevation and slope across individuals [2] [1]. These models enable simultaneous estimation of three crucial parameters: (1) between-individual variation in average behavior (personality), (2) between-individual variation in plasticity (individual-by-environment interaction), and (3) residual within-individual variation (predictability) [2].

The random regression approach represents an ideal method for exploring individual variation in BRNs because it can be applied whenever environmental gradients are quantified and individuals are repeatedly assayed across different environmental contexts [2]. For nonlinear selection analysis, recent advances propose generalized multilevel models that estimate stabilizing, disruptive, and correlational selection on reaction norm parameters using flexible Bayesian frameworks [1]. This approach simultaneously accounts for uncertainty in reaction norm parameters and their potentially nonlinear fitness effects, avoiding inferential bias that has historically challenged this field [1].

Experimental Design Considerations

Proper BRN analysis requires repeated behavioral measurements of individuals across defined environmental gradients. The experimental protocol must specify: the environmental gradient (clearly defined, biologically relevant contexts), replication (sufficient repeated measures per individual across contexts), standardization (controlled conditions to minimize extraneous variation), and fitness measures (quantifiable fitness components to estimate selection) [1] [4].

The number of required measurements per individual depends on the magnitude of behavioral plasticity and the research questions. For complex nonlinear reaction norms or when investigating individual variation in predictability, more extensive replication is necessary [1]. Experimental designs should also account for potential temporal effects (order of testing) and carryover effects that might influence behavioral measurements [4].

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Behavioral Reaction Norm Research

| Method | Application | Requirements | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Regression | Estimating individual variation in intercepts and slopes | Repeated measures across environmental gradient | Variance components, individual plasticity estimates |

| Bayesian Multilevel Models | Estimating nonlinear selection on RN parameters | Large sample sizes, fitness data | Selection gradients, posterior distributions |

| Quantitative Genetic Pedigree Analysis | Decomposing I and I×E into genetic and environmental sources | Pedigree data, multiple related individuals | Heritability estimates, genetic correlations |

| Generalized Linear Mixed Models | Analyzing non-Gaussian behavioral and fitness data | Appropriate link functions, distributional assumptions | Parameter estimates on transformed scales |

Experimental Protocols for BRN Assessment

Standardized Territorial Aggression Assay

Purpose: To quantify individual variation and plasticity in territorial aggression using acoustic playback stimuli [4].

Materials:

- Loudspeaker with integrated music player (MUVO 2c, Creative, Singapore)

- Digital voice recorder (ICD-PX333, Sony, Tokyo, Japan)

- Laser rangefinder (DLE 50, Bosch, Stuttgart, Germany)

- Black PVC disc (radius = 15 cm)

- Calibration equipment for acoustic stimuli

Procedure:

- Pre-experiment setup: Survey population daily to sample all adult males. capture frogs using transparent plastic bags to minimize stress. record identification photographs (dorsal on mm-paper for body size, ventral for belly patterns). Confirm identifications using pattern-matching software (Wild-ID) [4].

Stimulus preparation: Create artificial calls featuring average spectral and temporal parameters of the species. Generate multiple variations within natural variation to prevent habituation. For size manipulation, create stimuli at extremes of natural peak frequency range (±3 SD) to mimic large (low frequency) and small (high frequency) intruders [4].

Experimental setup: Position loudspeaker centered on PVC disc at precisely 2m from focal male using laser rangefinder. Experimenter stands 1m behind setup. Allow 30s acclimatization after setup installation [4].

Behavioral recording: Initiate playback and record: latency to orient head/body toward intruder, latency to jump toward intruder, whether subject touches the disc. End trial when focal male touches disc or after 5min playback. Exclude trials if focal male calls (indicates perceived extraneous intrusion) [4].

Experimental design: First, test individuals multiple times (3-4 repetitions) with "average sized intruder" signals to establish baseline aggressiveness. Subsequently, test each individual with low and high frequency calls in random order to assess plasticity [4].

Data analysis: Calculate repeatability for latency measures. Use random regression to estimate individual intercepts (personality) and slopes (plasticity). Test for correlation between personality and plasticity [4].

Systematic Protocol Development and Validation

Protocol writing specifications: Each experimenter must write protocols sufficiently thorough that a trustworthy, non-lab-member psychologist could execute them correctly. Protocols should include specific sections: Setting up, Greeting and consent, Instructions and practice, Monitoring or on-call procedures, Saving and break-down, and Exceptions/unusual events [5].

Protocol testing and validation:

- Self-testing: Researcher runs through protocol without bringing unwritten knowledge, identifying necessary additions [5].

- Lab-member testing: Another lab member performs setup and procedure exactly as protocol instructs. Protocol revised based on feedback until executable correctly [5].

- PI authorization: Principal investigator reviews complete protocol and authorizes naive participant observation [5].

- Supervised run: Senior lab member observes setup, instructions/practice, and breakdown. Post-run discussion identifies necessary changes [5].

- Clearance to begin: After successful supervised run with no changes needed, researcher cleared to begin full data collection [5].

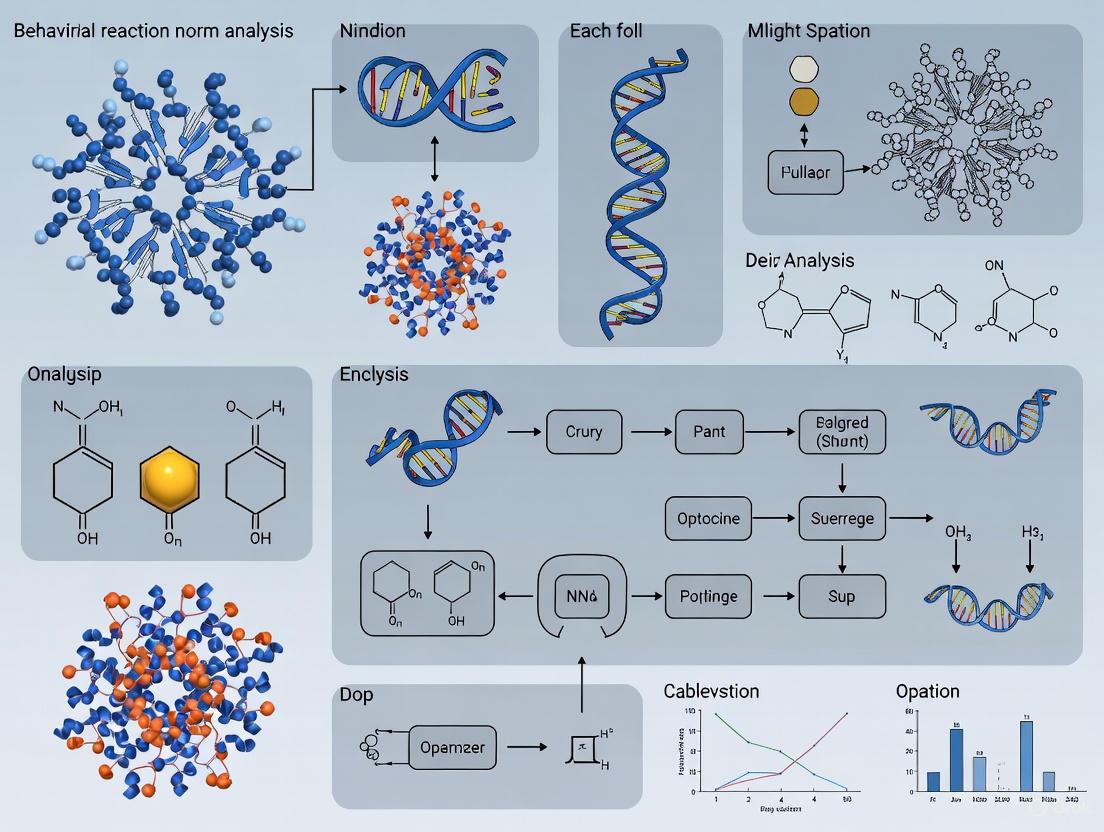

Visualization Framework

Conceptual Relationship Mapping

Experimental Workflow for BRN Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Behavioral Reaction Norm Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in BRN Research | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Tracking | Digital voice recorder (Sony ICD-PX333), Laser rangefinder (Bosch DLE 50) | Precise quantification of behavioral responses and spatial relationships | High-fidelity audio recording, millimeter precision distance measurement |

| Stimulus Delivery | Portable loudspeaker (Creative MUVO 2c), Acoustic calibration software | Controlled presentation of standardized environmental stimuli | Flat frequency response, calibrated output levels |

| Identification & Morphometrics | Digital camera, mm-paper background, Wild-ID software | Individual identification and morphological characterization | Pattern matching algorithms, size standardization |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (MCMCglmm, brms), Stan probabilistic programming | Multilevel modeling of reaction norm parameters | Bayesian inference, random regression capabilities |

| Environmental Monitoring | Data loggers, Environmental sensors | Quantification of environmental gradients | Temperature, humidity, light intensity measurements |

Data Structure and Reporting Standards

Optimal Data Structure for BRN Analysis

Data for behavioral reaction norm analysis requires a longitudinal structure with repeated measures nested within individuals. The essential variables include: individual identifier, measurement occasion, environmental context value, behavioral response measurement, and fitness components (if assessing selection) [1] [6]. Each row should represent a single behavioral observation, maintaining the granularity of repeated measurements while enabling aggregation at the individual level for personality estimates [6].

Proper data structure distinguishes between dimensions (qualitative variables like individual ID, environmental context) and measures (quantitative variables like latency scores, aggression indices) [6]. The data should be formatted in tables with clear headers, appropriate alignment (numeric data right-aligned, text left-aligned), and consistent units of measurement to facilitate analysis and reproducibility [7].

Reporting Standards and Data Transparency

Comprehensive reporting of experimental protocols requires 17 fundamental data elements to facilitate reproduction of experiments: detailed workflow descriptions, specific parameters for reagents and equipment, troubleshooting guidance, and exact environmental conditions [8]. Key reporting elements include:

- Sample characteristics: Complete description of subjects, including individual identifiers, morphological measures, and relevant history [8] [4].

- Stimulus specifications: Exact parameters of experimental stimuli, calibration methods, and delivery protocols [4].

- Environmental context: Precise quantification of environmental gradients and contextual variables [2] [1].

- Behavioral measures: Clear operational definitions of all recorded behaviors, measurement techniques, and scoring criteria [5] [4].

- Statistical models: Complete specification of analytical models, including random effects structure, prior distributions (Bayesian analyses), and model selection criteria [1].

Adherence to these reporting standards ensures that behavioral reaction norm studies can be properly evaluated, replicated, and incorporated into meta-analyses, advancing the field's understanding of personality-plasticity integration.

Behavioral reaction norm analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding how an individual's genotype can produce a range of behavioral phenotypes across different environmental contexts [9]. This approach moves beyond static behavioral assessment to model how behaviors change in response to environmental gradients, pharmacological interventions, or developmental experiences. At the heart of this analytical method lie three core parameters: the intercept, slope, and residual. These parameters collectively describe and quantify the pattern of behavioral plasticity, offering crucial insights for researchers in neuroscience, pharmacology, and drug development.

The intercept represents the expected behavioral phenotype in a baseline or reference environment, while the slope quantifies the sensitivity and direction of behavioral change across environments. The residuals capture the remaining unexplained variance, indicating measurement error, transient influences, or potential missing variables from the model [10]. Proper interpretation of these parameters enables researchers to distinguish between fixed behavioral traits and environmentally-responsive behaviors, a critical distinction when evaluating how pharmacological agents might modulate behavior across different contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Representation

The mathematical foundation of reaction norm analysis rests on a linear model that describes the relationship between behavioral expression and environmental context. This framework can be extended to incorporate various fixed and random effects, making it particularly valuable for complex experimental designs in behavioral pharmacology.

Mathematical Formulation

The basic reaction norm equation can be represented as:

[ P = G + E + G \times E ]

Where:

- ( P ) represents the behavioral phenotype

- ( G ) represents the genotypic value

- ( E ) represents the environmental context

- ( G \times E ) represents the genotype-by-environment interaction [10]

In practice, this conceptual equation is implemented as a linear mixed model:

[ y{ij} = \beta0 + \beta1X{1j} + \beta2X{2j} + \cdots + \betapX{pj} + ui + \epsilon{ij} ]

Where ( y{ij} ) is the behavioral measurement for individual ( i ) in environment ( j ), ( \beta0 ) is the intercept, ( \beta1 ) to ( \betap ) are slope coefficients for environmental variables, ( ui ) represents individual-specific random effects, and ( \epsilon{ij} ) represents the residual error.

Parameter Interpretation Framework

Table 1: Interpretation of Core Parameters in Behavioral Reaction Norm Analysis

| Parameter | Statistical Meaning | Biological/Behavioral Meaning | Interpretation Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Predicted behavioral value when all environmental predictors equal zero | Baseline behavioral tendency or predisposition in reference environment | Only interpret when zero value of environmental predictors is meaningful [11] |

| Slope | Change in behavioral measurement per unit change in environmental variable | Behavioral plasticity or sensitivity to environmental context [9] | Assumes linear relationship; may miss non-linear responses [10] |

| Residual | Difference between observed and predicted behavior (Residual = Observed - Predicted) [12] | Unexplained variance due to measurement error, transient factors, or model misspecification | Patterns in residuals may indicate missing variables or non-linear relationships [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Estimation

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Behavioral Phenotyping Across Environments

Purpose: To estimate intercept and slope parameters for individual behavioral reaction norms across systematically varied environmental conditions.

Materials:

- Experimental Subjects: Appropriate model organisms (e.g., rodents, zebrafish, Drosophila)

- Environmental Manipulation System: Capable of precise control over environmental variables (e.g., temperature, lighting, social density)

- Behavioral Tracking: Automated behavioral analysis system (e.g., EthoVision, AnyMaze, custom tracking software)

- Data Analysis Platform: Statistical software with mixed-effects modeling capabilities (e.g., R, Python, BGLR) [13]

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Define the environmental gradient (e.g., 5 discrete levels of environmental challenge)

- Randomization: Randomize the order of environmental exposure across subjects to control for order effects

- Behavioral Testing: Expose each subject to all environmental conditions with appropriate washout periods between tests

- Data Collection: Record behavioral endpoints of interest (e.g., anxiety-like behaviors, social interactions, cognitive performance)

- Model Fitting: For each subject, fit the linear model: Behavior = Intercept + Slope × Environment

- Parameter Extraction: Extract individual-specific intercept and slope estimates for subsequent analysis

Troubleshooting:

- If residual plots show systematic patterns, consider adding additional fixed effects or transforming variables [12]

- For non-normal residuals, consider generalized linear mixed models with appropriate error distributions [13]

Protocol 2: Residual Analysis for Model Diagnostics

Purpose: To evaluate model fit and identify potential missing variables or non-linear relationships through systematic residual analysis.

Materials:

- Fitted reaction norm models from Protocol 1

- Statistical software with diagnostic plotting capabilities (e.g., R, Python with matplotlib/seaborn)

- Qualtrics Stats iQ or equivalent residual diagnostic tools [12]

Procedure:

- Residual Calculation: Compute residuals for each observation using the formula: Residual = Observed - Predicted [12]

- Residual Plotting: Create the following diagnostic plots:

- Predicted vs. Residual values

- Environmental variable vs. Residuals

- Q-Q plot of residuals to assess normality

- Pattern Detection: Examine plots for:

- Homoscedasticity (equal variance across predictions)

- Systematic patterns indicating model misspecification

- Outliers that may disproportionately influence parameter estimates

- Model Refinement: Based on diagnostic results, consider:

- Adding additional environmental covariates

- Applying transformations to variables

- Including polynomial terms for non-linear relationships

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Healthy residuals show no systematic patterns and are approximately normally distributed around zero [12]

- Fan-shaped patterns in residual plots indicate heteroscedasticity, suggesting the need for variable transformation

- Curvilinear patterns suggest missing non-linear terms in the model

Visualization and Analysis Framework

Conceptual Framework of Behavioral Reaction Norms

Diagram 1: Reaction norm conceptual framework showing how genotype and environment interact to produce phenotypic outcomes through the core parameters.

Experimental Workflow for Parameter Estimation

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow showing the sequential process from study design through parameter estimation and validation.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Behavioral Reaction Norm Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (BGLR package) [13], Python (rxn_network) [14], SAS, Stata | Parameter estimation, model fitting, and statistical inference for reaction norm models |

| Behavioral Tracking | EthoVision, AnyMaze, ToxTrac, custom Python/Matlab scripts | Automated quantification of behavioral phenotypes across environmental conditions |

| Environmental Control | Precision environmental chambers, automated feeding systems, social isolation apparatus | Systematic manipulation of environmental variables to create reaction norm gradients |

| Data Management | Electronic laboratory notebooks, laboratory information management systems (LIMS) | Organization of longitudinal behavioral data across multiple environmental conditions |

| Visualization Tools | Graphviz (DOT language), ggplot2 (R), matplotlib (Python) | Creation of reaction norm plots, residual diagnostics, and conceptual diagrams |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development

The application of reaction norm analysis in pharmaceutical research enables more nuanced understanding of how pharmacological interventions interact with environmental contexts to produce behavioral outcomes. This approach is particularly valuable for:

6.1 Context-Dependent Drug Efficacy: By modeling behavioral reaction norms before and after drug administration, researchers can identify whether compounds specifically alter behavioral plasticity (slope changes) versus general behavioral suppression/enhancement (intercept changes). This distinction helps identify compounds that specifically increase resilience to environmental challenges versus those that produce generalized effects.

6.2 Individualized Treatment Prediction: The BGLR software package enables Bayesian analysis of reaction norm models, allowing researchers to incorporate prior knowledge and generate predictive distributions for individual responses to pharmacological interventions across environments [13]. This approach supports the development of personalized medicine strategies in behavioral pharmacology.

6.3 Gene-Environment-Pharmacology Interactions: Reaction norm analysis provides a natural framework for testing how genetic backgrounds modulate responses to pharmacological treatments across different environmental contexts. This triple interaction (G×E×P) can be modeled by including random slopes for genetic strains or genotypes and testing their interaction with drug treatment conditions.

The deconstruction of intercepts, slopes, and residuals in behavioral reaction norm analysis provides researchers with a powerful analytical framework for understanding behavioral plasticity. These core parameters enable quantitative assessment of how behaviors change across environments, how individuals differ in their behavioral plasticity, and how pharmacological interventions might modulate these relationships. The experimental protocols and analytical tools outlined in this application note provide a foundation for implementing this approach in basic behavioral research and applied drug development contexts. As precision medicine advances in neuroscience, reaction norm approaches will become increasingly valuable for identifying compounds that specifically target maladaptive patterns of behavioral plasticity while preserving context-appropriate responses.

Understanding how organisms adapt to changing environments is a central challenge in evolutionary biology, with significant implications for drug development and public health. This article explores the integration of quantitative genetic models with the study of adaptive phenotypes, focusing on the analysis of behavioral reaction norms. The theoretical frameworks discussed here provide a foundation for predicting evolutionary trajectories and interpreting complex genotype-phenotype relationships in biomedical research, particularly in the context of personalized treatment approaches and understanding substance use disorders [15] [16].

The rapid environmental changes observed globally have heightened interest in "evolutionary rescue"—the process by which threatened populations avoid extinction by adapting to altered environments [17]. Contemporary research demonstrates that evolutionary change can be fast enough to be observed in present-day populations, directly affecting population and community dynamics [17]. Within this context, reaction norm analysis emerges as a powerful framework for understanding how phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in different environments—contributes to adaptive processes.

Theoretical Foundations

Quantitative Genetic Models of Adaptation

Quantitative genetics provides the mathematical foundation for predicting evolutionary change in complex traits. The cornerstone of this approach is the Lande equation, which describes how mean phenotypes change in response to selection [17]. For a single trait, the equation is expressed as:

[ \Delta \bar{z} = G \beta ]

Where (\Delta \bar{z}) represents the change in mean phenotype after one generation of selection, (G) is the additive genetic variance, and (\beta) is the selection gradient at time (t) [17]. This equation can be expanded to multivariate cases where multiple traits are considered simultaneously, with the response to selection influenced by the genetic covariance matrix [17].

A critical concept in evolutionary potential is the Fundamental Theorem of Natural Selection (FTNS), which quantitatively predicts the increase in a population's mean fitness as the ratio of its additive genetic variance in absolute fitness ((VA(W))) to its mean absolute fitness ((\bar{W})) [18]. This ratio, (VA(W)/\bar{W}), indicates a population's immediate adaptive capacity to current conditions based on its present genetic composition [18]. However, empirical estimation of these parameters remains challenging, limiting practical application of the FTNS despite its theoretical importance.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Quantitative Genetic Models of Adaptation

| Parameter | Symbol | Interpretation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive genetic variance | (G) | Variance in breeding values | Determines potential response to selection |

| Selection gradient | (\beta) | Relationship between trait and fitness | Direction and strength of selection |

| Phenotypic variance | (P) | Total observable variance | (P = G + E) (with E environmental variance) |

| Additive genetic variance in absolute fitness | (V_A(W)) | Genetic variance for fitness | Direct measure of adaptive capacity |

| Rate of adaptation | (V_A(W)/\bar{W}) | Proportional increase in mean fitness | Predicts population recovery potential |

Reaction Norm Framework

The reaction norm concept provides a framework for understanding phenotypic variation as a function of environmental conditions. Formally, a reaction norm is a function that maps an environmental parameter to an expected value of a phenotypic trait [19]. If we denote the environmental parameter as (X) and the phenotypic trait as (Y), the reaction norm (h(\cdot)) gives the expected value for (Y) given the environmental state (x) as (E(y|x) = h(x)) [19].

This framework unifies two seemingly opposing concepts: phenotype diversification through environmental variation (plasticity) and the limitation of phenotypic variation through developmental buffering (canalization) [19]. Both plasticity and canalization can be considered adaptive traits that have evolved in response to environmental variation, with the reaction norm itself representing the evolved trait [19].

The reaction norm approach is particularly valuable for studying labile traits—those that can change throughout an individual's lifetime, such as behaviors, physiological states, and some morphological characteristics [1]. These traits can be decomposed into several parameters:

- RN intercept: The expected phenotype in the average environment

- RN slope: The expected change in phenotype in response to environmental variation

- RN residual: The magnitude of stochastic variability within a given environment [1]

Table 2: Reaction Norm Parameters and Their Evolutionary Significance

| Parameter | Definition | Interpretation | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RN Intercept | Expected phenotype in average environment | Baseline trait value | Underlying genetic quality or strategy |

| RN Slope | Change in phenotype per unit environmental change | Responsiveness to environment | Adaptive plasticity; learning rate |

| RN Residual | Stochastic variability within a given environment | Predictability/precision | Environmental sensitivity or robustness |

| G×E Interaction | Genetic variation in reaction norm slope | Individual differences in plasticity | Potential for evolution of plasticity |

Genetic Architecture of Phenotypic Plasticity

The genetic architecture underlying phenotypic variation plays a crucial role in determining how traits respond to environmental change. Genetic loci can contribute to phenotypic variation through additive effects (acting independently) or nonadditive effects (including dominance and epistasis) [20]. The impact of these genetic variants on the phenotype depends on both the genetic background and environmental context [20].

Recent research has identified specific classes of genetic elements that modify correlations among quantitative traits. These relationship Quantitative Trait Loci (rQTL) affect trait correlations by changing the expression of existing genetic variation through gene interaction [21]. This mechanism allows natural selection to directly enhance the evolvability of complex organisms along lines of adaptive change by increasing correlations among traits under simultaneous directional selection while reducing correlations among traits not under simultaneous selection [21].

Methodological Protocols

Estimating Reaction Norm Parameters

The estimation of individual reaction norms requires repeated measurements of phenotypes across different environmental contexts. The following protocol outlines the recommended approach for reaction norm parameter estimation:

Protocol 1: Reaction Norm Estimation Using Multilevel Models

Experimental Design

- Select subjects from a population with known pedigree or genetic relationships

- Expose each subject to multiple environmental conditions in controlled or natural settings

- Ensure sufficient repeated measurements per individual across environmental gradients

- Record relevant fitness measures (survival, reproduction) when possible

Data Collection

- Quantify environmental variables on continuous scales when possible

- Measure phenotypic traits of interest with appropriate precision

- Record fitness components relevant to the research question

- Note: For behavioral traits, ensure measurements are ecologically relevant

Statistical Analysis

- Use multilevel, mixed-effects models to partition variance components

- Model individual intercepts and slopes as random effects

- Include fixed effects for population-level patterns

- For non-Gaussian phenotypes, employ appropriate link functions [1]

Parameter Estimation

- Extract Best Linear Unbiased Predictors (BLUPs) for individual reaction norm parameters

- Estimate variance components for intercept, slope, and residual

- Calculate heritability of reaction norm components when pedigree data available

Model Validation

- Check model assumptions (normality of residuals, etc.)

- Perform cross-validation to assess predictive accuracy

- Use posterior predictive checks in Bayesian framework [1]

Estimating Nonlinear Selection on Reaction Norms

Traditional approaches often fail to capture the complexity of selection on reaction norms. The following protocol describes a Bayesian framework for estimating nonlinear selection:

Protocol 2: Estimating Nonlinear Selection Using Bayesian Methods

Prerequisite Data

- Individual reaction norm parameters from Protocol 1

- Fitness measurements for each individual

- Sufficient sample size (simulations suggest N > 100 for adequate power) [1]

Model Specification

- Use generalized multilevel models with appropriate distribution for fitness data

- Include directional and quadratic terms for reaction norm parameters

- Specify priors based on biological knowledge when available

- Account for uncertainty in reaction norm parameters and their fitness effects simultaneously [1]

Implementation in Stan

- Code model in Stan probabilistic programming language

- Run multiple Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains

- Check convergence using (\hat{R}) statistics

- Ensure effective sample size sufficient for reliable inference

Interpretation of Results

- Directional selection gradients indicate selection on mean values

- Quadratic selection gradients indicate stabilizing/disruptive selection

- Correlational selection gradients indicate selection on parameter combinations

Integrating Genetic Architecture Analysis

Understanding the genetic basis of reaction norms requires specialized approaches to identify loci contributing to phenotypic plasticity:

Protocol 3: Mapping Genetic Architecture of Plasticity

Population Design

- Use genetically diverse populations (e.g., diallel crosses, natural isolates)

- Ensure sufficient genetic variation for detecting G×E interactions

- Consider using model organisms with known genetic variants

Environmental Manipulation

- Implement controlled environmental gradients relevant to the phenotype

- Include sufficient replication across genotypes and environments

- Measure phenotypes with high precision to detect subtle effects

Genotyping and QTL Mapping

- Perform genome-wide sequencing or genotyping

- Conduct QTL mapping for trait means across environments

- Perform specific analyses for G×E interactions (e.g., reaction norm QTL)

- Test for rQTL that affect trait correlations [21]

Network Analysis

- Construct genetic interaction networks from epistatic interactions

- Identify hub loci with disproportionate influence on phenotypic variation

- Examine network properties across different environments [20]

Visualization of Theoretical Framework

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between genetic architecture, reaction norms, and adaptive phenotypes:

Reaction norms translate genetic and environmental influences into phenotypic expression, which is then evaluated by the fitness landscape. Adaptive phenotypes that increase fitness subsequently influence genetic architecture through evolutionary processes.

Experimental Workflow for Reaction Norm Analysis

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for empirical studies of reaction norms in evolutionary and biomedical contexts:

Comprehensive workflow for reaction norm studies, from experimental design through data collection and analysis to practical application in evolutionary biology and biomedical research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Reaction Norm Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Drosophila melanogaster, Mus musculus | Genetic studies of plasticity | Genetic diversity, generation time, phenotypic assays |

| Genotyping Platforms | Whole genome sequencing, SNP arrays, targeted sequencing | Genotyping for QTL mapping | Coverage, resolution, cost |

| Environmental Chambers | Controlled temperature, humidity, light cycles | Standardized environmental gradients | Precision, control parameters |

| Behavioral Assay Systems | Open field, maze designs, sensor systems | Quantifying behavioral plasticity | Ecological relevance, automation |

| Statistical Software | R packages (lme4, MCMCglmm, rstan), specialized scripts | Multilevel modeling, Bayesian inference | Flexibility, computational efficiency |

| Biobanking Resources | Tissue/DNA banks, long-term storage | Preservation of genetic material | Sample integrity, tracking systems |

| WRN inhibitor 19 | WRN inhibitor 19, MF:C40H52F4N6O6, MW:788.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tannagine | Tannagine, MF:C21H27NO5, MW:373.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

The theoretical frameworks of quantitative genetics and reaction norm analysis have significant implications for drug development and precision medicine. Understanding genetic variation in drug response is fundamental to pharmacogenomics, which aims to deliver "the right drug for the right patient at the right dose and time" [16]. This approach represents a shift from the traditional "one drug fits all" model toward personalized treatment strategies [16].

In substance use disorders (SUDs), for example, genetic factors play a significant role, with heritability estimates around 50% for alcohol use disorder [15]. Genome-wide association studies have identified genomic regions harboring risk variants associated with SUDs, enabling the discovery of putative causal genes and improving understanding of genetic relationships among disorders [15]. This knowledge facilitates the development of polygenic scores that can predict disease risk and inform treatment strategies.

The integration of reaction norm thinking is particularly relevant for improving reproducibility in preclinical research. Rather than viewing biological variation as noise to be eliminated through standardization, a reaction norm perspective recognizes that environmental differences across laboratories can interact with genotypes to produce systematic differences in outcomes [19]. This understanding suggests that introducing systematic heterogeneity in experimental designs may actually improve external validity and reproducibility compared to rigorous standardization approaches [19].

For rare genetic disorders such as Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), genetics-enabled clinical trials with molecularly defined subpopulations can inform drug efficacy and safety profiling [22]. In these contexts, collecting DNA in clinical trials to assess potential underlying genetic factors related to drug safety is critical [22]. This approach allows researchers to distinguish between adverse events related to the drug itself versus those related to genetic predispositions in specific subpopulations.

The integration of quantitative genetics with reaction norm frameworks provides powerful theoretical and methodological approaches for understanding adaptive phenotypes. These frameworks allow researchers to move beyond static views of traits to dynamic models that incorporate environmental sensitivity, genetic constraints, and evolutionary potential.

The protocols and methodologies outlined in this article provide a foundation for investigating the genetic architecture of phenotypic plasticity and its role in adaptation. As environmental change accelerates and personalized medicine advances, these approaches will become increasingly important for predicting evolutionary trajectories, developing targeted therapies, and understanding complex disease etiologies.

Future research should focus on extending these frameworks to more complex traits, integrating across biological levels from genes to ecosystems, and developing more sophisticated statistical tools for estimating selection on reaction norms in natural populations. Such advances will enhance our ability to predict and manage adaptive responses in both natural and clinical contexts.

Behavioral Syndromes, Correlated Plasticities, and Coping Styles

Application Notes

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

Behavioral syndromes represent suites of correlated behaviors expressed either within a given behavioral context or across different contexts [23] [24]. This concept describes between-individual consistency in behavioral tendencies, where individuals with specific behavioral types maintain their rank order across different situations [25]. For example, an individual that is more aggressive than others in territorial contests might also be bolder than others when facing predators [26].

Correlated plasticities refer to how behavioral syndromes can influence or constrain an individual's behavioral plasticity—their ability to adjust behavior in response to environmental changes [27] [1]. Recent research emphasizes that behavioral syndromes may predict flexibility to fluctuations in the environment, with implications for social competence [27].

Coping styles represent a specific category of behavioral syndrome, typically categorized along a proactive-reactive continuum [28] [27]. Proactive individuals tend to be more impulsive, risk-taking, and routine-driven, whereas reactive individuals are more cautious, flexible, and responsive to environmental changes [28]. These styles represent consistent individual differences in how animals cope with stress [27].

Key Behavioral Syndromes and Their Ecological Implications

Table 1: Major Categories of Behavioral Syndromes and Their Characteristics

| Syndrome Category | Behavioral Correlations | Ecological Context | Fitness Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boldness-Aggression | Positive correlation between boldness under predation risk and aggression toward conspecifics [25] [26] | Foraging, mating, predator-prey interactions [26] | Bold/aggressive types gain better resources but suffer higher predation; reverse for shy/types [23] |

| Activity-Exploration | Correlation between general activity level, exploration of novel environments, and foraging intensity [26] | Resource acquisition, dispersal, invasion of novel habitats [26] | Active explorers find food/mates faster but face higher predation and energy costs [23] |

| Proactive-Reactive Coping | Suite of correlated behavioral and physiological responses to stress [28] [27] | Response to environmental stressors, social conflict [28] | Proactive: better in stable conditions; Reactive: superior in variable environments [28] |

Mechanisms and Underlying Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between underlying mechanisms, behavioral syndromes, and their ecological consequences.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework illustrating how genetic, neuroendocrine, and environmental mechanisms shape behavioral syndromes, which in turn influence behavioral plasticity and social competence, ultimately affecting fitness outcomes.

Neurobiological and Physiological Substrates

The physiology underlying coping styles involves complex neuroendocrine interactions. The serotonergic and dopaminergic input to the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens appears particularly relevant to different coping styles [28]. Additionally, neuropeptides including vasopressin and oxytocin have important implications for coping style expression [28]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis activity, corticosteroids, and plasma catecholamines were traditionally thought to have a direct relationship with coping style, though recent evidence suggests this relationship may not be directly causal [28].

In the excitatory neural network model of plasticity, spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) serves as the fundamental mechanism through which repeated patterns of activation strengthen functional connections between neural populations [29]. This mechanism is consistent with findings that BBCI (Bidirectional Brain-Computer Interface) conditioning can artificially induce plasticity through precisely timed spike-triggered stimulation [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Behavioral Syndromes in Wild Populations

Application: This protocol is adapted from field studies of Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) to assess how behavioral syndromes influence social plasticity and competence in natural settings [27].

Materials and Reagents:

- Focal animal observation equipment (binoculars, video cameras)

- Behavioral coding software (e.g., BORIS, Observer XT)

- GPS units for spatial data collection

- Weather monitoring equipment

- Data processing and statistical analysis software (R, Python)

Procedure:

- Behavioral Phenotyping:

- Conduct focal animal sampling for minimum 60-minute sessions per individual

- Record frequencies of: short-term affiliative behaviors (embraces, touches), facial displays (open mouths), aggressive interactions (contact aggression), and species-specific behaviors (e.g., tree shakes) [27]

- Calculate individual scores for established behavioral syndromes (e.g., "Excitability" similar to bold-shy axis) through principal component analysis [27]

Social Plasticity Assessment:

- Map grooming social networks by recording all grooming initiations and receptions

- Quantify social network connectivity (degree centrality) for each individual

- Monitor changes in network position across environmental gradients: anthropogenic pressure, temperature fluctuations, food availability [27]

Data Analysis:

- Use generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to test relationships between behavioral syndrome scores and social plasticity

- Include random effects for individual identity and group membership

- Test specifically whether less "excitable" (shyer) individuals show greater plasticity in affiliative responses to social environment changes [27]

Expected Outcomes: Studies using this approach have demonstrated that individuals with lower "excitable" scores show greater social plasticity, being more likely to adjust grooming initiation based on bystander presence and increasing social connectivity during higher anthropogenic pressure [27].

Protocol 2: Reaction Norm Analysis for Selection Studies

Application: This protocol uses advanced statistical methods to estimate nonlinear selection on individual reaction norms, facilitating tests of adaptive theory for labile traits in wild populations [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Individual identification system (tags, bands, or natural markings)

- Repeated measures of phenotype and fitness components (survival, reproductive success)

- Environmental monitoring data

- Bayesian statistical software (Stan with R/Python interfaces)

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Obtain repeated measurements of labile traits (behavioral, physiological) across environmental contexts

- Record fitness components (e.g., seasonal reproductive output, survival intervals)

- Quantify relevant environmental gradients (temperature, resource availability, predation risk)

Reaction Norm Modeling:

- Fit multilevel, mixed-effects models to estimate individual reaction norm parameters:

- Intercepts: Expected phenotype in average environment

- Slopes: Plasticity across environmental gradient

- Residuals: Stochastic phenotypic variability (predictability) [1]

- Use appropriate link functions for non-Gaussian traits

- Fit multilevel, mixed-effects models to estimate individual reaction norm parameters:

Selection Analysis:

- Implement generalized multilevel models in Bayesian framework to estimate:

- Directional selection (β): Selection on population means of RN parameters

- Quadratic selection (γ): Stabilizing, disruptive, and correlational selection on RN parameters [1]

- Account for uncertainty in both RN parameters and their fitness effects

- Implement generalized multilevel models in Bayesian framework to estimate:

Model Validation:

- Use posterior predictive checks to validate model fit

- Conduct simulation-based calibration to verify unbiased inference

Expected Outcomes: This approach enables robust estimation of nonlinear selection on reaction norms, providing insight into how behavioral plasticity evolves in heterogeneous environments. Simulation studies indicate desirable power for hypothesis tests with large sample sizes [1].

Protocol 3: Artificial Induction of Neural Plasticity

Application: This protocol describes methods for inducing specific plastic changes in neural circuits using bidirectional brain-computer interfaces (BBCI), based on experimental work in non-human primates [29].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bidirectional BCI System | Multi-electrode arrays with both recording and stimulation capabilities [29] | Reads neural activity and delivers precisely timed electrical stimulation |

| Neural Signal Processor | Real-time spike detection and classification algorithms [29] | Identifies action potentials from specific neurons for triggering stimulation |

| Microstimulation Equipment | Biphasic current pulses (typical parameters: 10-100 μA, 200 Hz) [29] | Activates neural populations at target sites |

| EMG Recording System | Intramuscular or surface electrodes with amplification [29] | Measures functional output of motor cortex conditioning |

| Computational Model | Probabilistic spiking network with STDP rules [29] | Predicts outcomes of conditioning protocols and optimizes parameters |

Procedure:

- Surgical Preparation:

- Implant multi-electrode arrays in motor cortex sites (e.g., "Recording" site and "Stimulation" site)

- Verify electrode placement through functional mapping

Baseline Connectivity Assessment:

- Measure evoked muscle responses (EMG) to intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) at both sites

- Establish baseline functional connectivity between neural populations

Spike-Triggered Conditioning:

- Configure BBCI to detect spikes from a specific neuron in "Recording" site

- Program stimulation delivery to entire population in "Stimulation" site after fixed delay (d†)

- Employ critical delay intervals consistent with STDP rules (typically 1-30ms) [29]

- Maintain conditioning protocol for extended period (typically 24-48 hours in freely behaving animals)

Post-Conditioning Assessment:

- Re-measure functional connectivity using ICMS-EMG protocols

- Compare evoked responses pre- and post-conditioning

- Track persistence of induced changes over days to weeks

Experimental Workflow:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for artificial induction of neural plasticity using bidirectional brain-computer interfaces, showing the sequence from surgical preparation through conditioning to analysis of outcomes.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol typically produces strengthened functional connectivity from recorded to stimulated sites, with efficacy strongly dependent on spike-stimulus delay following STDP-like timing rules. Effects are apparent after approximately 24 hours of conditioning and can persist for several days [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Analytical Tools for Behavioral Syndrome Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Coding Systems | BORIS, Observer XT, EthoVision [27] | Standardized quantification of behavioral frequencies, durations, and sequences |

| Social Network Analysis | UCINET, SOCPROG, igraph (R) [27] | Mapping and analyzing social relationships and network positioning |

| Coping Style Assessment | COPE Inventory, Ways of Coping Questionnaire, Coping Strategies Questionnaire [28] | Standardized categorization of proactive vs. reactive coping styles |

| Physiological Monitoring | Cortisol/CORT assays, heart rate monitors, telemetry systems [28] [27] | Quantifying physiological stress responses correlated with behavioral syndromes |

| Neural Circuit Tools | Bidirectional BCIs, microstimulation systems, multi-electrode arrays [29] | Artificial induction and measurement of neural plasticity |

| Statistical Modeling | Bayesian multilevel models (Stan, BRMS), GLMMs [1] | Analyzing reaction norms and selection on behavioral plasticity |

| Environmental Monitoring | GPS loggers, temperature sensors, food availability measures [27] [1] | Quantifying environmental gradients that interact with behavioral syndromes |

| Hdac8-IN-10 | Hdac8-IN-10, MF:C18H30N4O, MW:318.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rauvotetraphylline A | Rauvotetraphylline A, MF:C20H26N2O3, MW:342.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Considerations

When applying these protocols, several methodological considerations are essential:

Cross-Contextual Measurement: Behavioral syndromes are defined by correlations across contexts, requiring standardized behavioral measures in multiple situations (e.g., foraging, predator defense, social interaction) [23] [25].

Temporal Scale: Both short-term (behavioral plasticity) and long-term (behavioral type consistency) measurements are necessary to fully characterize behavioral syndromes [1].

Environmental Variance: Reaction norm analyses require sufficient environmental variation to accurately estimate individual plasticity slopes [1].

Network Effects: In social species, individual behavioral traits interact with group-level social structure, necessitating multilevel modeling approaches [27].

These protocols provide a comprehensive toolkit for investigating the mechanisms, consequences, and adaptive significance of behavioral syndromes, correlated plasticities, and coping styles across multiple levels of biological organization.

Behavioral Reaction Norms (BRNs) provide a powerful quantitative framework for understanding how an individual's phenotypic traits respond to environmental variation. In ecology, this concept is used to study how animals' behaviors change across different contexts, capturing both their average level of behavior (personality) and their responsiveness to environmental change (plasticity) [30]. When applied to pharmacology, BRNs enable researchers to move beyond population-level averages and instead model how individual patients or biological systems exhibit predictable patterns of response to pharmaceutical compounds across varying contexts.

The core parameters of an individual reaction norm include the intercept (expected phenotype in an average environment), slope (responsiveness to measured environmental factors), and residual (stochastic variability within a given environment) [1]. These parameters form the statistical backbone for analyzing individuality in drug response and toxicity. This approach represents a paradigm shift from static drug response assessments toward dynamic models that capture how individuals vary in their sensitivity to both therapeutic effects and adverse reactions across different biological environments.

Theoretical Framework: BRNs as Targets of Selection in Drug Development

The BRN framework conceptualizes drug response phenotypes as probabilistic functions with parameters that predict the expectation (μ) and dispersion (σ) of an individual's phenotypic response to a drug across measurable aspects of their biological environment [1]. This perspective allows researchers to test hypotheses about which aspects of drug response are under selection pressure during therapeutic interventions.

Reaction Norm Parameters

Table 1: Core Parameters of Pharmacological Reaction Norms

| Parameter | Symbol | Pharmacological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RN Intercept | μ₀, μ₀j | Expected drug response phenotype in the average biological environment or baseline state |

| RN Slope | βₓ, βₓj | Expected change in drug response per unit change in a measured biological factor |

| RN Residual | σ₀, σ₀j | Magnitude of unpredictable variability in drug response within a given biological state |

Contemporary evolutionary frameworks emphasize that these RN parameters can be direct targets of selection, leading to differential patterns of adaptation in changing environments [1]. In pharmaceutical contexts, this translates to understanding how genetic and epigenetic factors shape individual reaction norms to drug therapies, ultimately determining therapeutic success or failure.

Computational Methods for BRN Analysis in Drug Response

Modern computational approaches have dramatically enhanced our ability to estimate and analyze BRNs in pharmacological contexts. Several cutting-edge methodologies demonstrate how machine learning can capture the complex individuality in drug response and toxicity.

Contrastive Learning for Drug and Cell Line Representations

The SiamCDR framework leverages contrastive learning within a Siamese neural network to enhance the expressiveness of drug and cell line representations for predicting cancer drug response [31]. This approach projects drugs and cell lines into embedding spaces that encode similarities of gene targets for drugs and cancer types for cell lines, respectively. The underlying intuition is that drugs with similar targets will have similar effects, and drug efficacies among cells of the same cancer type should be more similar than among cells of different cancers [31].

Experimental Protocol: Contrastive Learning for Drug Response Prediction

- Data Collection: Gather drug-cell line response matrices with corresponding drug structures and cell line transcriptomic profiles.

- Reference Drug Selection: Represent drugs via their structural similarity to a set of reference compounds.

- Cell Line Representation: Generate cell line representations where each dimension represents the output of an Elastic Net model trained on transcriptomic data to predict sensitivity to a reference drug.

- Similarity Preservation: Use contrastive loss to ensure the embedding spaces preserve relationship structures associated with drug mechanisms of action and cell line cancer types.

- Response Prediction: Apply a dense neural network to the Hadamard product of drug and cell line representations to predict cancer drug response.

This method has demonstrated enhanced performance relative to state-of-the-art approaches like RefDNN and DeepDSC, with classifiers exhibiting more balanced reliance on drug- and cell line-derived features when making predictions [31].

Multimodal Deep Learning for Toxicity Prediction

Advanced deep learning frameworks integrate multiple data modalities to predict chemical toxicity, addressing the critical need for comprehensive safety assessments in drug development.

Experimental Protocol: Multimodal Toxicity Prediction

- Data Curation: Combine chemical property data and molecular structure images from diverse sources such as PubChem and eChemPortal.

- Image Processing: Utilize a Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture pre-trained on ImageNet-21k and fine-tuned on molecular structure images to extract image-based features.

- Tabular Data Processing: Employ a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to process numerical chemical property data including molecular weight, logP, and topological surface area.

- Feature Fusion: Implement joint intermediate fusion to combine image and numerical features into a unified representation.

- Multi-label Prediction: Design the model for simultaneous evaluation of diverse toxicological endpoints through multi-label classification.

This multimodal approach has demonstrated impressive performance, with the Vision Transformer component achieving an accuracy of 0.872, an F1-score of 0.86, and a Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) of 0.9192 in toxicity predictions [32].

Quantitative Assessment of BRN-Based Models

Table 2: Performance Comparison of BRN-Inspired Drug Response Models

| Model | Average Pcell@5 (Trained Cancers) | Average Pcell@5 (Novel Cancers) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepDSC (Baseline) | 0.421 | 0.388 | Robust to incomplete data; uses generic fingerprints |

| SiamCDRLR | 0.489* | 0.451* | Enhanced representations; more personalized prioritizations |

| SiamCDRRF | 0.491* | 0.453* | Balanced feature reliance; tailored predictions |

| SiamCDRDNN | 0.490* | 0.452* | Captures complex nonlinear relationships |

*Significant improvement over DeepDSC (Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.05) [31]

The performance metrics reveal that models incorporating BRN principles significantly outperform traditional approaches, particularly in their ability to prioritize effective drugs for both trained-on and novel cancer types. This demonstrates the value of capturing individual variation in drug response patterns.

Visualization of BRN Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: BRN Framework for Drug Response. This diagram illustrates how individual reaction norm parameters mediate the relationship between biological environment and drug response phenotypes, creating a feedback loop through therapeutic fitness and selection pressure.

Diagram 2: BRN Analysis Workflow for Drug Development. This workflow outlines the process from multi-modal data collection through representation learning to individualized therapeutic decision-making.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BRN Analysis in Pharmacology

| Reagent/Material | Function in BRN Analysis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Si-Fe-Mg Mixed Hydrous Oxide (SFM05905) | Adsorption material for toxic agent analysis | Removal of arsenic contaminants from experimental systems [33] |

| Magnesium-Modified High-Sulfur Hydrochar (MWF) | Heavy metal adsorption capacity | Remediation of cadmium and lead pollution in experimental environments [33] |

| Bismuth-Iron Oxide Composite (BFO) | Photocatalytic degradation catalyst | Breakdown of pharmaceutical waste compounds like cytarabine [33] |

| Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) | Effective sorbents for extraction procedures | Separation and preconcentration of inorganic oxyanions in analytical samples [33] |

| Portable SpectroChip-Based Immunoassay Platform | Rapid quantification of toxic compounds | Detection of melamine in urine samples for toxicity assessment [33] |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) Architecture | Image-based feature extraction from molecular structures | Processing 2D structural images of chemical compounds for toxicity prediction [32] |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Processing numerical chemical property data | Handling tabular data representing chemical properties in multi-modal learning [32] |

| Rauvotetraphylline A | Rauvotetraphylline A, MF:C20H26N2O3, MW:342.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Griffithazanone A | Griffithazanone A, MF:C14H11NO4, MW:257.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: BRNs in Severe Adverse Drug Reaction Analysis

The case of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) following lamotrigine administration illustrates how BRN analysis could enhance our understanding of severe idiosyncratic drug reactions [34]. This life-threatening mucocutaneous condition represents an extreme individual response to a medication that is generally well-tolerated.

Clinical Protocol: Managing Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions

- Early Detection: Monitor for initial symptoms including high fever, widespread erythematous rash, and oral mucosal erosions.

- Immediate Intervention: Promptly discontinue the offending medication (e.g., lamotrigine) upon suspicion of severe reaction.

- Multidisciplinary Care: Coordinate across dermatology, ophthalmology, hematology, and nutrition specialists for comprehensive management.

- Immunomodulation: Administer intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 10g/day for one week to modulate the immune response.

- Supportive Care: Implement meticulous skin and mucosal surface care with appropriate topical treatments and fluid resuscitation.

- Progressive Monitoring: Track clinical improvement through indicators such as hs-CRP normalization and SCORTEN score reduction [34].

This case highlights the critical importance of recognizing individual variation in drug response and the potential for BRN frameworks to eventually predict which patients are at highest risk for such extreme reactions.

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

The integration of BRN analysis into mainstream pharmacology faces several implementation challenges but offers tremendous potential for advancing personalized medicine. Key challenges include the need for large-scale longitudinal data collection, development of standardized protocols for RN parameter estimation, and computational resources for complex multi-modal modeling.

Future research should focus on extending BRN frameworks to model dynamic therapeutic interventions across time, incorporating more sophisticated environmental characterizations, and developing clinical decision support tools that can operationalize BRN-based predictions for individual patients. The continued refinement of these approaches will ultimately enhance our ability to capture the essential individuality in drug response and toxicity, moving precision medicine from static genomic matching toward dynamic, predictive models of therapeutic outcomes.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches for Estimating Behavioral Reaction Norms

Behavioral Reaction Norms (BRNs) provide a powerful integrative framework for analyzing individual animal behavior, combining two key aspects of the behavioral phenotype: animal personality and individual plasticity [2]. Animal personality refers to consistent differences in behavior between individuals across time and contexts, while individual plasticity describes the capacity of an individual to adjust its behavior in response to environmental changes [2]. The BRN framework conceptualizes an individual's behavior as a reaction norm—a function that describes its behavioral phenotype across an environmental gradient. Rather than considering a single behavioral measurement, the relationship describing the behavioral response of an individual over an environmental context becomes the trait of interest for evolutionary analysis [2].

Random regression models (RRMs) serve as the primary statistical tool for estimating BRNs, enabling researchers to quantify interindividual variation in reaction norm elevations (personality) and slopes (plasticity) simultaneously [2]. These models allow for the decomposition of behavioral variation into individual (I) and individual-by-environment (I×E) components, providing a comprehensive understanding of how behaviors vary both between individuals and within individuals across contexts [2]. This approach has revolutionized behavioral ecology by offering a unified method to study personality and plasticity within a single adaptive framework.

Theoretical Foundation and Statistical Framework

Core Concepts of Behavioral Reaction Norms

The BRN approach is founded on several key conceptual principles that distinguish it from traditional behavioral analysis methods. First, it recognizes that the behavioral phenotype is not static but represents a dynamic response to environmental conditions. Second, it acknowledges that individuals may differ not only in their average level of behavior but also in how they respond to environmental variation [2]. This dual perspective enables researchers to address fundamental questions about the adaptive nature of behavioral variation and its evolutionary consequences.

When applying the BRN framework, the environmental gradient (context) must be clearly defined and measurable. This gradient can represent various factors including temporal changes, spatial variation, social context, or perceived risk [2]. The statistical model then estimates for each individual a linear reaction norm characterized by two parameters: elevation (the individual's average behavioral level) and slope (the individual's behavioral plasticity across environments). The correlation between elevation and slope across individuals in a population represents a crucial evolutionary parameter, indicating whether more aggressive or exploratory individuals, for instance, are more or less plastic in their behavioral responses [2].

Random Regression Model Specification

Random regression models provide the mathematical foundation for estimating BRNs. The basic random regression model for behavioral data can be represented as:

$$Y{ij} = \mu + \beta \times Ej + Ii + I{Ei} \times Ej + \epsilon{ij}$$

Where:

- $Y_{ij}$ is the behavioral observation for individual i in environment j

- $\mu$ is the population mean behavior

- $\beta$ is the population mean plasticity (fixed slope)

- $E_j$ is the environmental value for context j

- $I_i$ is the random intercept (personality) for individual i

- $I_{Ei}$ is the random slope (plasticity) for individual i

- $\epsilon_{ij}$ is the residual error

The model estimates variance components for $\sigma^2I$ (personality variance), $\sigma^2{IE}$ (plasticity variance), and their covariance $\sigma{I,I_E}$ [2]. These parameters collectively describe the structure of behavioral variation in the population and provide insights into evolutionary potential.

Table 1: Key Variance Components Estimated by Random Regression Models for BRN Analysis

| Component | Symbol | Biological Interpretation | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality Variance | $\sigma^2_I$ | Differences between individuals in average behavior | Indicates potential for personality evolution |

| Plasticity Variance | $\sigma^2{IE}$ | Differences between individuals in responsiveness to environment | Indicates potential for plasticity evolution |

| Elevation-Slope Covariance | $\sigma{I,IE}$ | Relationship between average behavior and responsiveness | Constrains independent evolution of personality and plasticity |

Experimental Protocols for BRN Estimation

Study Design and Data Collection

Implementing random regression for BRN analysis requires careful experimental design with repeated behavioral measurements across defined environmental contexts. The following protocol outlines the key steps for proper data collection:

Define Environmental Gradient: Establish a measurable environmental gradient relevant to the study species and research question. This could include risk levels (predator cues), resource availability, temperature, social density, or temporal sequences [2]. The gradient should encompass ecologically relevant variation experienced by the population.

Determine Sampling Scheme: Each individual must be assayed across multiple points along the environmental gradient. The number of repeated measurements per individual should balance statistical power with practical constraints, typically requiring at least 3-5 observations per individual across different environmental contexts [2].

Control for Testing Effects: Counterbalance or randomize the order of environmental presentations to control for habituation, sensitization, or carry-over effects between behavioral assays. Include appropriate acclimation periods to novel testing environments.

Standardize Behavioral Assays: Develop standardized protocols for behavioral testing to ensure consistency across individuals and contexts. This includes controlling for time of day, testing duration, and environmental conditions not being manipulated as part of the gradient.

Record Supplementary Data: Document individual characteristics (age, sex, size, condition) that might explain variation in personality or plasticity, and record precise environmental measurements for each behavioral observation.

Statistical Implementation with Random Regression

The analytical protocol for implementing random regression models proceeds through the following structured steps:

Data Preparation and Exploration:

- Organize data in long format with one row per behavioral observation

- Center and standardize the environmental gradient variable to improve model convergence

- Check for outliers and missing data

- Visualize raw data to identify individual reaction norms

Model Specification:

- Fit random regression models using mixed-model frameworks available in statistical software (e.g.,

lme4in R,PROC MIXEDin SAS) - Include fixed effects for relevant covariates (e.g., sex, age)

- Specify random intercepts and slopes for individuals, allowing correlation between them

- Select appropriate covariance structures for random effects

- Fit random regression models using mixed-model frameworks available in statistical software (e.g.,

Model Selection and Validation:

- Compare models with different random effect structures using information criteria (AIC, BIC)

- Validate model assumptions through residual analysis

- Check for homogeneity of variances across environmental contexts

- Assess potential for overfitting, particularly with complex random effect structures

Parameter Estimation and Interpretation:

- Extract variance components for personality ($\sigma^2I$) and plasticity ($\sigma^2{I_E}$)

- Calculate the correlation between elevation and slope ($\sigma{I,IE}$)

- Estimate fixed effects representing population-average patterns

- Visualize predicted reaction norms for the population and individual

Applications Across Biological Disciplines

Livestock Genomics and Production Traits

Random regression models have been extensively applied in animal breeding and genetics for analyzing longitudinal production traits. In dairy cattle, RRMs have been used to estimate genetic parameters for milk urea nitrogen (MUN) across lactation cycles [35]. These models enable the estimation of time-dependent genetic effects, capturing how genetic influences on traits change throughout different physiological stages [36].

The application of RRMs in livestock genomics typically involves:

- Test-day models for milk production traits that account for changes in genetic effects across lactation

- Longitudinal genetic evaluations that provide more accurate breeding value estimates compared to single-measurement models [36]

- Genome-wide association studies that identify time-dependent SNP effects, revealing genetic regions with specific effects at different production stages [37]

Table 2: Applications of Random Regression Models in Biological Research

| Field | Application | Key Advantage | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Ecology | Estimating behavioral reaction norms | Quantifies personality and plasticity simultaneously | [2] |

| Dairy Cattle Genetics | Milk urea nitrogen across lactation | Captures time-dependent genetic effects | [35] |

| Swine Production | Residual feed intake in growing pigs | Models longitudinal feed efficiency | [38] |

| Wild Bird Populations | Exploration behavior in great tits | Links individual variation to fitness | [2] |

Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, RRMs and related machine learning approaches are increasingly applied in drug discovery pipelines. While direct applications of BRNs in pharmaceutical contexts are emerging, the fundamental principles of modeling individual-specific responses over gradients align with key challenges in drug development [39] [40].

Potential applications include:

- Personalized medicine approaches that account for individual differences in drug response