Beyond the Average: Navigating Individual Variation in Drug Response for Precision Therapeutics

This article addresses the critical challenge of translating population-level data into effective treatments for individual patients in drug development.

Beyond the Average: Navigating Individual Variation in Drug Response for Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of translating population-level data into effective treatments for individual patients in drug development. It explores the foundational concepts of population means and individual variation, highlighting the limitations of a one-size-fits-all approach, as evidenced by the fact that over 99% of patients carry actionable pharmacogenomic variants. The content delves into advanced methodological frameworks like Population PK/PD and mixed-effects models designed to quantify and account for this variability. It further provides strategies for troubleshooting common issues in variability analysis and evaluates validation frameworks such as Individual and Population Bioequivalence. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this article synthesizes insights from clinical pharmacology, statistics, and systems biology to chart a path toward more personalized and effective medical treatments.

The Myth of the Average Patient: Understanding Sources of Individual Variability

Defining Population Mean vs. Individual Variation in a Clinical Context

In clinical research and drug development, a fundamental tension exists between the population mean—the average treatment effect observed across a study cohort—and individual variation—the differences in how specific patients or subgroups respond to an intervention [1]. This distinction is not merely statistical but has profound implications for patient care, drug development, and healthcare policy. The population mean provides the foundational evidence for evidence-based medicine, yet clinicians treat individuals whose characteristics, risks, and treatment responses may differ significantly from the population average [2] [1]. Understanding this dichotomy is essential for interpreting clinical trial results, optimizing therapeutic interventions, and making informed decisions that balance collective evidence with individualized care.

Conceptual Framework: Populations and Individuals

Understanding the Population Mean

In clinical research, the term "population" is a theoretical concept encompassing all individuals sharing a particular set of characteristics or all potential outcomes of a specific treatment [2] [3]. The population mean (often denoted as μ) represents the average value of a measured outcome (e.g., reduction in blood pressure, survival rate) across this entire theoretical group. Crucially, this parametric mean is almost never known in practice because researchers cannot measure every member of the population [3]. Instead, they estimate it using the sample mean (x̄) calculated from a subset of studied patients.

The precision of this estimation depends heavily on sample size and variability. As sample size increases, sample means tend to cluster more closely around the true population mean due to the cancellation of random sampling errors [3]. This statistical phenomenon is quantified by the standard error of the mean (S.E.), which decreases as sample size increases and is estimated using the formula S.E. = s/√n, where s is the sample standard deviation and n is the sample size [3].

The Reality of Individual Variation

In contrast to population averages, individual variation reflects the diversity of treatment responses among patients due to differences in genetics, comorbidities, concomitant medications, lifestyle factors, and disease heterogeneity [1]. This variation presents a critical challenge for clinical decision-making, as the "average" treatment effect reported in trials may not accurately predict outcomes for individual patients.

The problem is exemplified by the re-analysis of the GUSTO trial, which compared thrombolytic drugs for heart attack patients [1]. While the overall population results showed t-PA was superior to streptokinase, this benefit was primarily driven by a high-risk subgroup. Lower-risk patients received minimal benefit from the more potent and risky drug, yet the population-level results led to widespread adoption of t-PA for all eligible patients [1]. This demonstrates how population means can obscure clinically important variation in treatment effects across patient subgroups.

Table 1: Key Terminology in Population vs. Individual Analysis

| Term | Definition | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Population Mean | Average treatment effect across a theoretical population | Provides overall evidence for treatment efficacy; foundation for evidence-based medicine |

| Sample Mean | Average treatment effect observed in the studied patient sample | Estimate of population mean; precision depends on sample size and variability |

| Individual Variation | Differences in treatment response among individual patients | Explains why some patients benefit more than others from the same treatment |

| Standard Deviation | Measure of variability in individual patient outcomes | Quantifies the spread of individual responses around the mean |

| Standard Error | Measure of precision in estimating the population mean | Indicates how close the sample mean is likely to be to the true population mean |

Quantitative Comparisons: Effect Measures and Their Interpretation

Comparing Population Effect Measures

Clinical research employs various statistical measures to quantify treatment effects, each with distinct advantages and limitations for interpreting population-level versus individual-level implications [4]. Understanding these measures is essential for appropriate interpretation of clinical evidence.

Ratio measures, including risk ratios (RR), odds ratios (OR), and hazard ratios (HR), express the relative likelihood of an outcome occurring in the treated group compared to the control group [4]. These measures are useful for understanding the proportional benefit of a treatment but can be misleading because they communicate only relative differences rather than absolute differences. For example, an OR of 0.52 denotes a reduction of almost half in the risk of weaning in a breastfeeding intervention trial, but without knowing the baseline risk, the clinical importance is difficult to assess [4].

Absolute measures, particularly risk difference (RD), quantify the actual difference in risk between treated and untreated groups [4]. These measures are mathematically more intuitive and easier to interpret clinically. For instance, a study found that offering infants a pacifier once lactation was well established did not reduce exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months in a clinically meaningful way (RD = 0.004), meaning the percentage of exclusively breastfeeding babies at 3 months differed by only 0.4% [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Effect Measures in Clinical Research

| Effect Measure | Calculation | Interpretation | Example | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio (RR) | Risk in exposed / Risk in unexposed | Relative difference in risk | RR=1.3: 30% increased risk in exposed | Easy to understand; commonly used | Does not reflect baseline risk; can exaggerate importance of small effects |

| Odds Ratio (OR) | Odds in exposed / Odds in unexposed | Relative difference in odds | OR=0.52: 48% reduction in odds | Useful for case-control studies; mathematically convenient | Often misinterpreted as risk ratio; less intuitive |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | Hazard in exposed / Hazard in unexposed | Relative difference in hazard rates over time | HR=1.62: 62% increased hazard | Accounts for time-to-event data; uses censored observations | Requires proportional hazards assumption; complex calculation |

| Risk Difference (RD) | Risk in exposed - Risk in unexposed | Absolute difference in risk | RD=0.004: 0.4% absolute difference | Clinically intuitive; reflects actual risk change | Does not convey relative importance; depends on baseline risk |

Statistical Significance Versus Clinical Significance

A crucial distinction in interpreting clinical research is between statistical significance and clinical significance [4] [5] [6]. Statistical significance, conventionally defined by a p-value < 0.05, indicates that an observed effect is unlikely to be due to chance alone [4] [5]. However, statistical significance does not necessarily indicate that the effect is large enough to be clinically important.

Clinical significance denotes a difference in outcomes deemed important enough to create a lasting impact on patients, clinicians, or policy-makers [5]. The concept of minimal clinically important difference (MCID) represents "the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and excessive cost, a change in the patient's management" [5].

Alarmingly, contemporary research shows that most comparative effectiveness studies do not specify what they consider a clinically significant difference. A review of 307 studies found that only 8.5% defined clinical significance in their methods, yet 2.3% recommended changes in clinical decision-making, with 71.4% of these doing so without having defined clinical significance [5]. This demonstrates concerning over-reliance on statistical significance alone for clinical recommendations.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling

Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling represents a sophisticated approach to understanding both population trends and individual variations in drug response [7]. This methodology uses non-linear mixed-effects modeling to characterize drug behavior while accounting for inter-individual variability.

In a study of the novel sedative HR7056, researchers developed a three-compartment model to describe its pharmacokinetics in Chinese healthy subjects [7]. The model included population mean parameters for clearance (1.49 L·min⁻¹), central volume (2.1 L), and inter-compartmental clearances (0.96 and 0.27 L·min⁻¹), while also quantifying inter-individual variability [7]. The pharmacodynamic component used a "link" model to relate plasma concentrations to effect-site concentrations and a sigmoid inhibitory effect model to describe the relationship between HR7056 concentration and its sedative effects measured by Bispectral Index (BIS) and Modified Observer's Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (MOAA/S) scores [7].

The structural model for the relationship between effect-site concentration (Ce) and drug effect (E) was described using the equation: E = E₀ - (Iₘₐₓ × Ceᵞ)/(IC₅₀ᵞ + Ceᵞ) where E₀ is the baseline effect, Iₘₐₓ is the maximum possible reduction in effect, IC₅₀ is the concentration producing 50% of maximum effect, and γ is the Hill coefficient describing curve steepness [7].

Subgroup and Risk-Based Analysis

An alternative approach to address individual variation involves conducting subgroup analyses based on patient risk profiles [1]. This method involves developing mathematical models to predict individual patient outcomes based on their characteristics, then analyzing treatment effects across different risk strata.

In the GUSTO trial re-analysis, researchers used a risk model to divide patients into quartiles based on their baseline mortality risk [1]. They discovered that the highest-risk quartile accounted for most of the mortality benefit that gave t-PA its advantage over streptokinase [1]. Similarly, in the ATLANTIS B trial of t-PA for stroke, risk stratification revealed that patients at lowest risk of thrombolytic-related hemorrhage actually benefited from t-PA treatment, even though the overall trial results showed no net benefit [1].

These approaches demonstrate how analyzing trial results through the lens of individual variation can reveal treatment effects masked by population-level analyses and provide clinicians with better tools for individualizing treatment decisions.

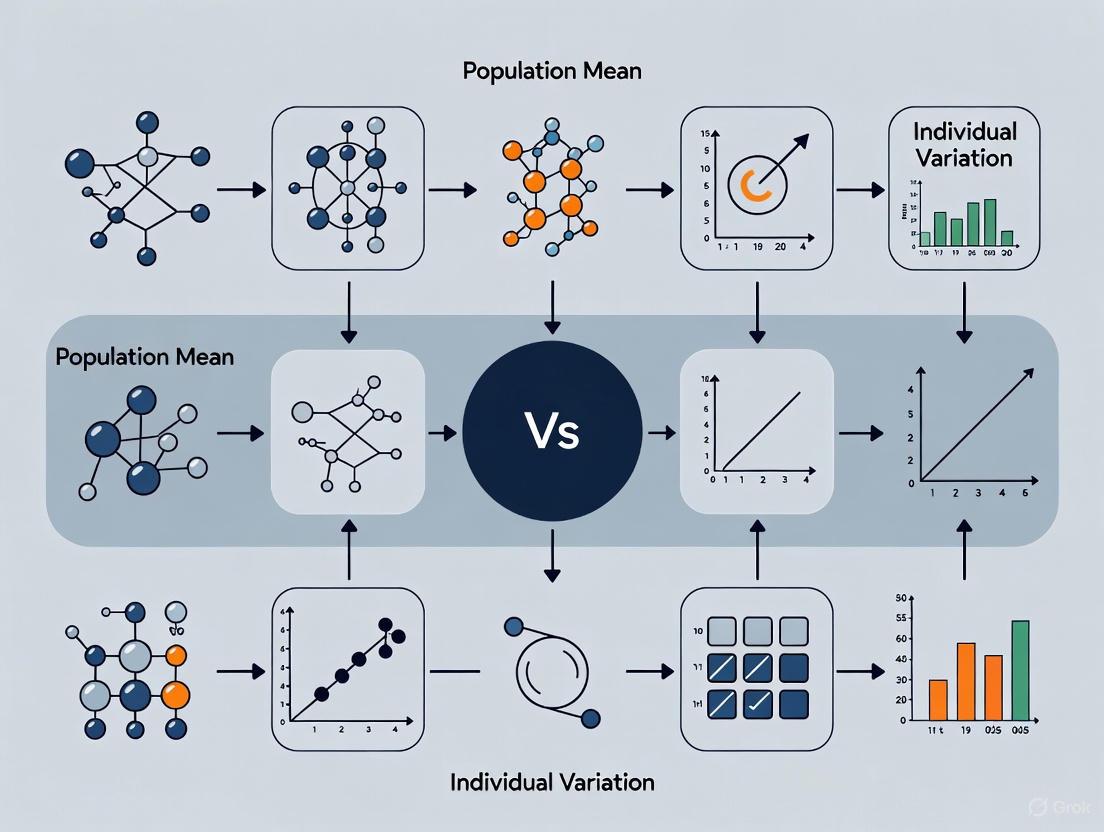

Visualizing the Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between population means and individual variation in clinical research, and how this relationship informs clinical decision-making:

Relationship Between Population and Individual Perspectives

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Population and Individual Analysis

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-linear Mixed Effects Modeling | Estimate population parameters while quantifying inter-individual variability | Population PK/PD analysis | Requires specialized software (NONMEM, Phoenix NLME); complex implementation but powerful for sparse data |

| Risk Stratification Models | Identify patient subgroups with different treatment responses | Post-hoc analysis of clinical trials | Enhances clinical applicability but requires validation; risk of overfitting |

| Confidence Intervals | Quantify precision of effect estimates | Reporting of all clinical studies | Preferred over p-values alone; provide range of plausible values for true effect [4] |

| Minimal Clinically Important Difference | Define threshold for clinically meaningful effects | Study design and interpretation | Should be specified a priori; can use validated standards or clinical judgment [5] |

| Standard Error Calculation | Estimate precision of sample mean | Sample size planning and interpretation | S.E. = s/√n; decreases with larger sample sizes [3] |

The tension between population means and individual variation represents a fundamental challenge in clinical research and practice. Population means provide essential evidence for treatment efficacy and form the foundation of evidence-based medicine, but they inevitably obscure important differences in how individual patients respond to interventions. The contemporary over-reliance on statistical significance, without adequate consideration of clinical significance or individual variation, risks leading to suboptimal treatment decisions that may harm some patients while helping others.

Moving forward, clinical research should embrace methodologies that explicitly address both population-level effects and individual variation, including population PK/PD modeling, risk-based subgroup analysis, and consistent application of clinically meaningful difference thresholds. By better integrating these approaches, researchers and clinicians can develop more nuanced therapeutic strategies that respect both collective evidence and individual patient differences, ultimately advancing toward truly personalized medicine.

In the pursuit of personalized medicine, a fundamental statistical challenge lies in distinguishing true individual response to treatment from the background variability inherent in all biological systems. The common belief that there is a strong personal element in response to treatment is not always based on sound statistical evidence [8]. Research into personalized medicine relies on the assumption that substantial patient-by-treatment interaction exists, yet in almost all cases, the actual evidence for this is limited [9]. This guide compares how different experimental designs and statistical approaches succeed or fail at isolating three critical variance components: between-patient, within-patient, and patient-by-treatment interaction. Understanding these components is essential for drug development professionals aiming to determine whether treatments should be targeted to specific patient subgroups or applied more broadly.

Defining the Key Variance Components

In clinical trials, the observed variation in outcomes arises from multiple distinct sources. Statisticians formally account for these sources of variability to draw accurate conclusions about treatment effects [10]. The table below defines the four fundamental components of variance that must be understood and measured.

Table 1: Core Components of Variance in Clinical Trials

| Component of Variation | Statistical Definition | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Between-Treatments (A) | Variation between treatments averaged over all patients [8] | The overall average effect of one treatment versus another |

| Between-Patient (B) | Variation between patients given the same treatments [8] | Differences in baseline severity, genetics, demographics, or comorbidities |

| Patient-by-Treatment Interaction (C) | Extent to which effects of treatments vary from patient to patient [8] | True individual response differences; the key to personalization |

| Within-Patient (D) | Variation from occasion to occasion when same patient is given same treatment [8] | Measurement error, temporal fluctuations, and environmental factors |

The relationship between these components can be visualized through the following conceptual framework:

Experimental Designs for Isolating Variance Components

Different clinical trial designs provide varying capabilities to isolate these variance components. The choice of design directly determines which components can be precisely estimated and which remain confounded.

Table 2: Identifiable Variance Components by Trial Design

| Trial Design | Description | Identifiable Components | Confounded "Error" Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Group | Patients randomized to a single course of one treatment for the trial duration [8] | Between-Treatments (A) [8] | B + C + D [8] |

| Classical Cross-Over | Patients randomized to sequences of treatments, with each treatment studied in one period [8] | A, B [8] | C + D [8] |

| Repeated Period Cross-Over | Patients treated with each treatment in multiple periods with randomization [8] | A, B, C [8] | D [8] |

| N-of-1 Trials | Single patient undergoes multiple treatment periods with randomization in a replicated design [11] | Within-patient (D) for that individual | Minimal when properly replicated |

The workflow below illustrates how these designs progressively isolate variance components:

Case Study: Replicate Cross-Over Design

A compelling case study demonstrates how replicate cross-over designs can successfully isolate patient-by-treatment interaction [11]. In this methodology:

- Patient Recruitment: Participants undergo multiple treatment periods with randomized sequences

- Replication: Each treatment is administered multiple times to the same patient

- Measurement: Outcomes are measured consistently across all periods

- Statistical Analysis: Random-effects models partition variance into its components

This design represents a "lost opportunity" in drug development, as it enables formal investigation of where individual response to treatment may be important [11]. The essential materials required for implementing such designs include specialized statistical software capable of fitting mixed-effects models (such as R, SAS, or Python with appropriate libraries), validated outcome measurement instruments, randomization systems, and data collection protocols that minimize external variability.

Quantitative Methods for Assessing Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

Variance-Ratio Meta-Analysis

When cross-over designs are not feasible, the variance-ratio (VR) approach provides an alternative method for detecting heterogeneous treatment effects in parallel-group RCTs [12]. This method compares the variance of post-treatment scores between intervention and control groups.

Experimental Protocol for VR Analysis:

- Extract post-treatment standard deviations from both arms of RCTs

- Calculate variance ratio (VR): VR = σ²treatment / σ²control

- Combine VRs across studies using meta-analytic techniques

- Interpret results: VR > 1 suggests heterogeneous treatment effects

Application Example: In PTSD treatment research, VR meta-analysis revealed that psychological treatments showed greater outcome variance in treatment groups compared to control groups, suggesting possible treatment effect heterogeneity [12]. However, similar analyses for antipsychotics in schizophrenia and antidepressants in depression showed no evidence for heterogeneous treatment effects [12].

Marginal Structural Models for Drug Interactions

Advanced statistical methods like marginal structural models (MSMs) with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) can assess causal interactions between drugs using observational data [13].

Methodological Workflow:

- Data Collection: Gather electronic health records or claims data with quadruplets (D₁, D₂, X, Y) for drug exposures, covariates, and outcomes

- Variable Selection: Use elastic net or other methods to identify confounding variables

- Propensity Score Estimation: Model probability of treatment assignment given covariates

- Weighting: Apply inverse probability of treatment weights to create balanced pseudopopulations

- Model Fitting: Estimate causal parameters using weighted generalized linear models

Table 3: Comparison of Methods for Detecting Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

| Method | Study Design | Key Assumptions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated Cross-Over | Experimental | No carryover effects, stable patient condition over time [8] | Impractical for long-term outcomes, high cost and complexity |

| Variance-Ratio | Parallel-group RCTs | Equal baseline variances, normally distributed outcomes [14] | Cannot distinguish mediated effects from true interaction [14] |

| Marginal Structural Models | Observational | No unmeasured confounding, positivity, correct model specification [13] | Requires large sample sizes, sensitive to model misspecification |

Statistical Toolkit for Variance Component Analysis

The following tools and techniques form the essential "research reagent solutions" for investigating variance components in drug development:

Table 4: Essential Methodological Toolkit for Variance Component Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Methods | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Designs | Repeated period cross-over, N-of-1 trials, Bayesian adaptive designs [8] [11] | Isolating patient-by-treatment interaction with maximal efficiency |

| Modeling Frameworks | Random-effects models, mixed models, marginal structural models, generalized estimating equations [8] [13] | Partitioning variance components while accounting for correlation structure |

| Causal Inference Methods | Inverse probability weighting, propensity score stratification, targeted maximum likelihood estimation [13] | Estimating treatment effect heterogeneity from observational data |

| Meta-Analytic Approaches | Variance-ratio meta-analysis, random-effects meta-regression [12] | Synthesizing evidence of heterogeneous treatment effects across studies |

Understanding these key statistical components has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development. Between-patient variance highlights the importance of patient recruitment strategies and baseline assessments. Within-patient variance sets the lower bound for detecting meaningful treatment effects. Most critically, patient-by-treatment interaction represents the theoretical upper limit for personalization—if this component is minimal, then personalized treatment approaches have little margin for improvement [12].

Each variance component informs different aspects of drug development: between-patient variance affects trial sizing and stratification strategies; within-patient variance determines measurement precision requirements; and patient-by-treatment interaction dictates whether targeted therapies or companion diagnostics are viable development pathways. By applying the appropriate experimental designs and statistical methods outlined in this guide, researchers can make evidence-based decisions about when and how to pursue personalized medicine approaches rather than relying on assumptions about variable treatment response [8] [9].

For decades, drug development and dosage optimization have predominantly followed a "one-size-fits-all" approach, based on average response in the general population. This paradigm, focused on the population mean, fails to account for profound individual variation in drug metabolism and efficacy, often resulting in treatment failure or adverse drug reactions (ADRs) for substantial patient subsets [15]. Pharmacogenomics (PGx) has emerged as a transformative discipline that bridges this gap by studying how genetic variations influence individual responses to medications [16].

Recent evidence reveals a striking consensus: over 97% of individuals carry clinically actionable pharmacogenomic variants that significantly impact their response to medications [15] [17]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the experimental evidence supporting this conclusion, detailing the methodologies, technologies, and findings that are reshaping drug development and clinical practice toward a more personalized approach.

Quantitative Evidence: The Prevalence of Actionable Pharmacogenomic Variants Across Populations

Global and Regional Prevalence Studies

Table 1: Prevalence of Actionable PGx Variants Across Population Studies

| Population Cohort | Sample Size | % Carrying ≥1 Actionable Variant | Number of Pharmacogenes Analyzed | Key Genes with High Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss Hospital Biobank | 1,533 | 97.3% | 13 | CYP2C19, CYP2D6, SLCO1B1, VKORC1 | [15] |

| General Swiss Population | 4,791 | Comparable to hospital cohort | 13 | CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, TPMT | [15] |

| Global 1000 Genomes | 2,504 | 55.4% carrying LoF variants | 120 | CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | [18] |

| European PREPARE Study | 6,944 | >90% | 12 | CYP2C19, CYP2D6, SLCO1B1 | [17] |

| Mayo Clinic Pilot | 1,013 | 99% | 5 | CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, SLCO1B1 | [17] |

The consistency of these findings across diverse populations and methodologies is remarkable. The Swiss biobank study concluded that "almost all participants carried at least one actionable pharmacogenetic allele," with 31% of patients actually prescribed at least one drug for which they carried a high-risk variant [15]. The PREPARE study, the largest prospective clinical trial to date, further demonstrated the clinical utility of this knowledge, reporting a 30% decrease in adverse drug reactions when pharmacogenomic information guided prescribing [17].

Population-Specific Variant Frequencies

Table 2: Differentiated Allele Frequencies Across Major Populations

| Pharmacogene | Variant/Diplotype | Functional Effect | European Frequency | East Asian Frequency | African Frequency | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | *2, *3 (Poor Metabolizer) | Reduced enzyme activity | 25-30% | 40-50% | 15-20% | Altered clopidogrel, antidepressant efficacy [16] |

| CYP2D6 | *4 (Poor Metabolizer) | Reduced enzyme activity | 15-20% | 1-2% | 2-5% | Codeine, tamoxifen response [17] |

| CYP2D6 | Gene duplication (Ultra-rapid) | Increased enzyme activity | 3-5% | 1-2% | 10-15% | Risk of toxicity from codeine [17] |

| DPYD | HapB3 (rs56038477) | Reduced enzyme activity | 1-2% | 0.5-1% | 3-5% | Fluoropyrimidine toxicity [15] |

| SLCO1B1 | *5 (rs4149056) | Reduced transporter function | 15-20% | 10-15% | 1-5% | Simvastatin-induced myopathy [19] |

Population-specific differences in variant frequencies underscore why population mean approaches to drug dosing fail for many individuals. As one analysis noted, "racial and ethnic groups exhibit pronounced differences in the frequencies of numerous pharmacogenomic variants, with direct implications for clinical practice" [20]. For example, the CYP2C19*17 allele associated with rapid metabolism occurs in approximately 20% of Europeans but is less common in other populations, significantly affecting dosing requirements for proton pump inhibitors and antidepressants [16].

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols for PGx Variant Detection

Next-Generation Sequencing Workflows

Figure 1: Next-Generation Sequencing PGx Analysis Workflow. The process transforms raw DNA data into clinically actionable recommendations through standardized bioinformatics steps.

The foundation of modern pharmacogenomics relies on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies that comprehensively characterize variation across pharmacogenes. A typical targeted NGS workflow includes:

DNA Isolation and Quality Control: High-molecular-weight DNA extraction, with quality verification via spectrophotometry and fluorometry [21].

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment: Fragmentation and adapter ligation followed by either:

- Hybridization capture using biotinylated probes targeting specific pharmacogenes

- Amplicon-based approaches using targeted PCR primers

- Targeted Adaptive Sampling with nanopore sequencing for real-time enrichment [17]

High-Throughput Sequencing: Using platforms such as:

- Illumina platforms (short-read)

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (long-read)

- PacBio SMRT sequencing (long-read) [17]

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment to reference genome (GRCh37/38)

- Variant calling and quality filtering

- Star allele definition using tools like Aldy, PyPGx, or StellarPGx

- Diplotype assignment and phenotype prediction [22]

A 2024 study demonstrated that targeted adaptive sampling long-read sequencing (TAS-LRS) achieved 25x on-target coverage while simultaneously providing 3x off-target coverage for genome-wide variants, enabling accurate, haplotype-resolved testing of 35 pharmacogenes [17].

Genotyping Arrays and Functional Validation

For clinical applications focusing on known variants, genotyping arrays provide a cost-effective alternative:

- DNA Amplification and Fragmentation

- Hybridization to Custom Arrays containing probes for known PGx variants

- Fluorescence Detection and Genotype Scoring

- Functional Validation of novel variants via:

- In vitro enzyme activity assays using expressed recombinant enzymes

- Cell-based models to assess drug metabolism and transport

- Clinical pharmacokinetic studies correlating genotypes with drug exposure [21]

As highlighted in recent research, "stringent computational assessment methods and functional validation using experimental assays" are crucial for establishing the clinical validity of novel pharmacogenomic variants [21].

The Evolving PGx Landscape: Star Alleles and Clinical Interpretation

Dynamic Nature of Pharmacogenomic Nomenclature

Figure 2: Pharmacogenomic Clinical Interpretation Pipeline. Genetic variants are translated into clinical recommendations through standardized nomenclature systems and clinical guidelines.

The star allele nomenclature system provides standardized characterization of pharmacogene variants, but this system is highly dynamic. Analysis of PharmVar database updates reveals substantial evolution:

- 471 core alleles added between versions 1.1.9 and 6.2

- 49 core alleles redefined or removed during this period

- Updates impact clinical interpretation - 19.4% of diplotypes in reference datasets require revision [22]

This dynamic landscape necessitates regular updates to clinical decision support systems and genotyping algorithms to maintain accuracy. As one study concluded, "outdated allele definitions can alter therapeutic recommendations, emphasizing the need for standardized approaches including mandatory PharmVar version disclosure" [22].

Clinical Guideline Development

Consortia including the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) have developed guidelines for over 100 gene-drug pairs with levels of evidence ranging from A-D [16] [19]. As of 2024, CPIC has published guidelines for 132 drugs with pharmacogenomic associations [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacogenomic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PGx Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | DNA Standards | GeT-RM samples, Coriell Institute collections | Assay validation, inter-laboratory comparison |

| Genotyping Arrays | Targeted Genotyping | PharmacoScan, Drug Metabolism Array, Custom Panels | Cost-effective screening of known PGx variants |

| Sequencing Panels | Targeted NGS | Illumina TruSight, Thermo Fisher PharmacoScan | Comprehensive variant detection in ADME genes |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Star Allele Callers | Aldy, PyPGx, StellarPGx, Stargazer | Diplotype assignment from sequencing data |

| Functional Assay Kits | Enzyme Activity | P450-Glo, Transporter Activity Assays | Functional validation of novel variants |

| Database Resources | Curated Knowledge | PharmGKB, PharmVar, CPIC Guidelines | Clinical interpretation, allele definitions |

These research tools enable comprehensive pharmacogenomic investigation from initial discovery to clinical implementation. The GeT-RM (Genetic Testing Reference Materials) program provides particularly valuable reference materials with experimentally validated genotypes for method validation and quality control [22].

The evidence is unequivocal: over 97% of individuals carry clinically actionable pharmacogenomic variants that significantly impact drug response. This reality fundamentally challenges the traditional population mean approach to drug development and dosing. The convergence of decreasing sequencing costs, standardized clinical guidelines, and robust evidence of clinical utility positions pharmacogenomics to transform therapeutic individualization.

Future directions include:

- Integration of rare variants into clinical prediction models

- Development of multi-gene panels for pre-emptive testing

- Implementation in electronic health records with clinical decision support

- Global expansion of population-specific pharmacogenomic resources

As one study aptly concluded, "implementing a genetically informed approach to drug prescribing could have a positive impact on the quality of healthcare delivery" [15]. The stark reality that actionable pharmacogenomic variants exist in the vast majority of patients represents both a challenge to traditional paradigms and an unprecedented opportunity for personalized medicine.

In the development and clinical application of pharmaceuticals, a fundamental tension exists between population-based dosing recommendations and individual patient response. The non-stimulant medication atomoxetine, used for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), exemplifies this challenge through its extensive pharmacokinetic variability primarily governed by the highly polymorphic cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme. Population-derived averages for atomoxetine metabolism provide useful starting points for dosing, but individual genetic makeup can dramatically alter drug exposure, efficacy, and safety profiles.

Understanding this variability is crucial for drug development professionals and clinical researchers seeking to optimize therapeutic outcomes. The case of atomoxetine demonstrates how pharmacogenetic insights can bridge the gap between population means and individual variation, potentially informing both clinical practice and drug development strategies for medications metabolized by polymorphic enzymes.

The CYP2D6 Enzyme and Genetic Basis of Variability

CYP2D6 Genetic Architecture

The CYP2D6 gene, located on chromosome 22q13.2, encodes one of the most important drug-metabolizing enzymes in the cytochrome P450 superfamily, responsible for metabolizing approximately 25% of all marketed drugs [23]. This gene exhibits remarkable polymorphism, with over 135 distinct star (*) alleles identified and cataloged by the Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium [24]. These alleles result from single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions/deletions, and copy number variations, which collectively determine an individual's metabolic capacity for CYP2D6 substrates.

- Normal function alleles: *1, *2, *35 (Activity score = 1)

- Decreased function alleles: *9, *17, *29, *41 (Activity score = 0.5)

- Severely decreased function alleles: *10 (Activity score = 0.25)

- No function alleles: *3, *4, *5, *6, *40 (Activity score = 0)

- Increased function alleles: Gene duplications (e.g., *1x2, *2x2) (Activity score = 2 per copy)

Phenotype Classification System

The combination of CYP2D6 alleles (diplotype) determines metabolic phenotype through an activity score system recommended by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) [24]:

- Poor Metabolizers (PM): Activity score = 0 (No functional enzyme activity)

- Intermediate Metabolizers (IM): Activity score = 0.25-1.0 (Reduced enzyme activity)

- Normal Metabolizers (NM): Activity score = 1.25-2.25 (Standard enzyme activity)

- Ultrarapid Metabolizers (UM): Activity score > 2.25 (Enhanced enzyme activity)

Population Distribution of CYP2D6 Phenotypes

The frequency of CYP2D6 phenotypes exhibits substantial interethnic variation, with important implications for global drug development and dosing strategies [24]. Normal and intermediate metabolizers represent the most common phenotypes across populations, but poor and ultrarapid metabolizers constitute significant minorities at higher risk for adverse drug reactions or therapeutic failure.

Table 1: Global Distribution of CYP2D6 Phenotypes

| Population | Poor Metabolizers (%) | Intermediate Metabolizers (%) | Normal Metabolizers (%) | Ultrarapid Metabolizers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European | 5-10% | 10-44% | 43-67% | 3-5% |

| Asian | ~1% | 39-46% | 48-52% | 0-1% |

| African | ~2% | 25-35% | 50-60% | 5-10% |

| Latino | 2-5% | 30-40% | 50-60% | 2-5% |

Atomoxetine Pharmacokinetics and CYP2D6-Mediated Metabolism

Metabolic Pathway of Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism primarily via the CYP2D6 pathway, resulting in formation of its major metabolite, 4-hydroxyatomoxetine, which is subsequently glucuronidated [25]. In CYP2D6 normal metabolizers, atomoxetine has an absolute bioavailability of approximately 63% due to significant first-pass metabolism, compared to 94% in poor metabolizers who lack functional CYP2D6 enzyme activity [25]. This metabolic difference fundamentally underpins the substantial variability in drug exposure observed across different CYP2D6 phenotypes.

Magnitude of Exposure Variability

Research has consistently demonstrated that CYP2D6 polymorphism results in profound differences in atomoxetine pharmacokinetics. Studies report 8-10-fold higher systemic exposure (AUC) in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers compared to extensive metabolizers following identical dosing [25]. In clinical practice, this variability can extend up to 25-fold differences in plasma concentrations between individuals with different CYP2D6 phenotypes receiving the same weight-adjusted dose [26]. This exceptional range of exposure represents one of the most dramatic examples of pharmacogenetically-determined pharmacokinetics in clinical medicine.

Table 2: Atomoxetine Pharmacokinetic Parameters by CYP2D6 Phenotype

| Parameter | Poor Metabolizers | Normal Metabolizers | Ultrarapid Metabolizers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioavailability | 94% | 63% | Reduced |

| AUC | 8-10 fold higher | Reference | Reduced |

| Cmax | Higher | Reference | Lower |

| Tmax | 2.5 hours | 1.0 hour | Similar to NM |

| Half-life | 21.6 hours | 5.2 hours | Shorter |

| Clearance | Significantly reduced | Reference | Increased |

Experimental Evidence and Clinical Correlations

CYP2D6 Genotype and Dosing Response Relationships

A 2024 double-blind crossover study examining ADHD treatment response investigated relationships between CYP2D6 phenotype and atomoxetine efficacy over a 4-week period [27]. The results identified statistically significant trends in how CYP2D6 phenotype modified the time-response relationship for ADHD total symptoms (p = 0.058 for atomoxetine). Additionally, the dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3/DAT1) 3' UTR VNTR genotype showed evidence of modifying dose-response relationships for atomoxetine (p = 0.029), suggesting potential pharmacodynamic influences beyond the pharmacokinetic effects of CYP2D6.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Clinical Outcomes

A comprehensive 2024 retrospective study of 385 children with ADHD provided critical insights into the relationship between CYP2D6 genotype, plasma atomoxetine concentrations, and clinical outcomes [26]. The investigation revealed that CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers exhibited 1.4-2.2-fold higher dose-corrected plasma atomoxetine concentrations compared to extensive metabolizers. Furthermore, intermediate metabolizers demonstrated a significantly higher response rate (93.55% vs. 85.71%, p = 0.0132) with higher peak plasma concentrations.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis established that patients receiving once-daily morning dosing exhibited more effective response when plasma atomoxetine concentrations reached ≥268 ng/mL (AUC = 0.710, p < 0.001) [26]. The study also identified concentration thresholds for adverse effects, with intermediate metabolizers experiencing more central nervous system and gastrointestinal adverse reactions at plasma concentrations of 465 ng/mL and 509 ng/mL, respectively.

Comparative Efficacy Across Metabolizer States

Research has demonstrated that while CYP2D6 genotype significantly influences atomoxetine pharmacokinetics, most children with ADHD who are CYP2D6 normal metabolizers or have specific DAT1 genotypes (10/10 or 9/10 repeats) respond well to both atomoxetine and methylphenidate after appropriate dose titration [27]. However, the trajectory of response differs across metabolizer states, with poor and intermediate metabolizers achieving therapeutic concentrations more rapidly at lower doses, while ultrarapid metabolizers may require higher dosing or alternative dosing strategies to achieve efficacy.

Research Methodologies for Investigating CYP2D6-Atomoxetine Relationships

Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling Approaches

Population pharmacokinetics has emerged as a powerful methodology for quantifying and explaining variability in drug exposure [28] [29]. Unlike traditional pharmacokinetic studies that intensively sample small numbers of healthy volunteers, population approaches utilize sparse data collected from patients undergoing treatment, enabling identification of covariates that influence drug disposition.

The mixed-effects modeling approach fundamental to population pharmacokinetics incorporates:

- Fixed effects: Structural model parameters (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution) and demographic/clinical factors that significantly influence pharmacokinetics (e.g., weight, genotype)

- Random effects: Variance model parameters including intersubject variability and residual unexplained variability

This methodology allows researchers to pool data from multiple sources with varying dosing regimens and sampling times, making it particularly valuable for studying special populations where intensive sampling is impractical [29].

Genotype-Guided Clinical Trial Design

Contemporary investigations of CYP2D6-atomoxetine relationships typically incorporate prospective genotyping with stratified enrollment to ensure representation across metabolizer phenotypes [27] [26]. The essential protocol elements include:

- Genotyping Methodologies: Targeted amplification followed by sequencing, microarray analysis, or real-time PCR for key CYP2D6 variant alleles

- Phenotype Assignment: Translation of diplotype to activity score and phenotype category using standardized CPIC guidelines

- Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Strategic sampling at steady-state with precise documentation of dosing-to-sampling intervals

- Clinical Outcome Assessment: Standardized rating scales (e.g., ADHD-RS, IVA-CPT) administered at baseline and following treatment initiation

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Correlation of plasma concentrations with both efficacy and adverse effect endpoints

Integrated Pharmacogenetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling

Advanced research approaches now integrate CYP2D6 genotyping with therapeutic drug monitoring and clinical response assessment to develop comprehensive exposure-response models [26]. These models account for both the pharmacokinetic variability introduced by CYP2D6 polymorphism and potential pharmacodynamic modifiers such as the dopamine transporter (SLC6A3/DAT1) genotype, enabling more precise prediction of individual patient response to atomoxetine therapy.

Visualization of Atomoxetine Metabolism and Research Workflow

Atomoxetine Metabolic Pathway

Atomoxetine Metabolic Pathway: This diagram illustrates the primary metabolic pathway of atomoxetine, highlighting the crucial role of CYP2D6 in converting the parent drug to its hydroxylated metabolite prior to elimination.

Research Methodology Workflow

Pharmacogenomic Research Workflow: This flowchart outlines the comprehensive methodology for investigating CYP2D6-atomoxetine relationships, integrating genotyping, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical outcome assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for CYP2D6-Atomoxetine Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Technologies | TaqMan allelic discrimination assays, PCR-RFLP, sequencing panels, microarrays | CYP2D6 allele definition and diplotype assignment |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS systems, HPLC-UV | Quantification of plasma atomoxetine and metabolite concentrations |

| Clinical Assessment Tools | ADHD-RS, IVA-CPT, Conners' Rating Scales | Objective measurement of treatment efficacy and symptom improvement |

| Pharmacokinetic Software | NONMEM, Phoenix NLME, Monolix | Population PK modeling and covariate analysis |

| Reference Materials | PharmVar CYP2D6 allele definitions, CPIC guidelines | Standardized genotype to phenotype translation and dosing recommendations |

| Biobanking Resources | DNA extraction kits, blood collection tubes, temperature-controlled storage | Sample management for retrospective and prospective analyses |

Clinical Implementation and Dosing Recommendations

CPIC Guideline Recommendations

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium has established evidence-based guidelines for atomoxetine dosing based on CYP2D6 genotype [30] [31]. These recommendations represent the formal translation of pharmacogenetic research into clinical practice:

- Poor Metabolizers: Consider initiating with 50% of the standard dose and titrate to efficacy or maximum plasma concentrations of approximately 400 ng/mL

- Intermediate Metabolizers: Initiate with standard dosing but consider slower titration with therapeutic drug monitoring

- Normal Metabolizers: Standard dosing recommendations apply with routine monitoring

- Ultrarapid Metabolizers: May require higher doses (up to 1.8 mg/kg/day) to achieve therapeutic exposure

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Targets

Based on recent evidence, the following plasma concentration thresholds have been proposed for optimizing atomoxetine therapy [26]:

- Efficacy Threshold: ≥268 ng/mL for patients receiving once-daily morning dosing

- CNS Adverse Effects: ≥465 ng/mL in intermediate metabolizers

- GI Adverse Effects: ≥509 ng/mL in intermediate metabolizers

These thresholds highlight the importance of considering both genotype and drug concentrations when individualizing atomoxetine therapy.

The case of CYP2D6 genotype and atomoxetine exposure provides a compelling illustration of the critical tension between population means and individual variation in drug development and clinical practice. While population averages provide essential starting points for dosing recommendations, the 25-fold variability in atomoxetine exposure mediated by CYP2D6 polymorphism necessitates a more personalized approach.

The integration of pharmacogenetic testing, therapeutic drug monitoring, and population pharmacokinetic modeling offers a powerful framework for optimizing atomoxetine therapy across diverse patient populations. This case study underscores the importance of incorporating pharmacogenetic principles throughout the drug development process, from early clinical trials through post-marketing surveillance, to ensure both efficacy and safety in the era of precision medicine.

For drug development professionals, the atomoxetine example demonstrates the value of prospective pharmacogenetic screening in clinical trials and the importance of considering genetic polymorphisms when establishing dosing recommendations for medications metabolized by polymorphic enzymes. As pharmacogenetics continues to evolve, this approach promises to enhance therapeutic outcomes across numerous drug classes and clinical indications.

A fundamental challenge in modern pharmacology lies in the critical difference between the population average and individual patient response. While drug development and regulatory decisions often focus on the doses that are, on average, safe and effective for a population, the reality is that "many individuals possess characteristics that make them unique" [32]. This inter-individual variability means that a fixed dose can result in a wide range of drug exposures and therapeutic outcomes across different patients. Non-genetic factors—including age, organ function, drug interactions, and lifestyle—constitute major sources of this variability, profoundly influencing drug disposition and effects. Understanding these contributors is essential for moving beyond the "average patient" model and toward more precise, individualized therapeutic strategies that account for the complete physiological context of each patient [32].

The Impact of Aging on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

Physiological Changes with Aging

Aging is a multifaceted physiological process characterized by the progressive decline in the function of various organ systems. It involves a "gradual loss of cellular function and the systemic deterioration of multiple tissues," which increases susceptibility to age-related diseases [33]. At the molecular level, aging is associated with several hallmarks, including genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which collectively contribute to the overall functional decline [33] [34]. This decline manifests as a reduced homeostatic capacity, making it more challenging for older adults to maintain physiological balance under stress, including the stress imposed by medication regimens [35].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Changes in the Elderly

Pharmacokinetics, which encompasses the processes of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), undergoes significant changes with advancing age. Table 1 summarizes the key age-related physiological changes and their impact on drug PK.

Table 1: Age-Related Physiological Changes and Their Pharmacokinetic Impact

| Pharmacokinetic Process | Key Physiological Changes with Aging | Impact on Drug Disposition | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Decreased gastric acidity; Delayed gastric emptying; Reduced splanchnic blood flow [35] | Minimal clinical change for most drugs; Potential alteration for drugs requiring acidic environment or active transport [35] | Generally, no dose adjustment solely for absorption changes. |

| Distribution | ↑ Body fat (20-40%); ↓ Lean body mass (10-15%); ↓ Total body water [35] | ↑ Volume of distribution for lipophilic drugs (e.g., diazepam); ↓ Volume of distribution for hydrophilic drugs (e.g., digoxin) [35] | Lipophilic drugs have prolonged half-lives; hydrophilic drugs achieve higher plasma concentrations. |

| Metabolism | Reduced hepatic mass and blood flow; Variable changes in cytochrome P450 activity [35] | ↓ Hepatic clearance for many drugs; Increased risk of drug accumulation [35] | Dose reductions often required for hepatically cleared medications. |

| Excretion | ↓ Renal mass and blood flow; ↓ Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [35] | ↓ Renal clearance for drugs and active metabolites [35] | Crucial to estimate GFR and adjust doses of renally excreted drugs. |

Pharmacodynamic (PD) Changes in the Elderly

Pharmacodynamics, which describes the body's biological response to a drug, also alters with age. Older patients often exhibit increased sensitivity to various drug classes, even at comparable plasma concentrations [35]. For instance, they experience heightened effects from central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs like benzodiazepines, leading to more pronounced sedation and impaired performance [35]. This increased sensitivity may stem from factors such as "loss of neuronal substance, reduced synaptic activity, impaired brain glucose metabolism, and rapid drug penetration into the central nervous system" [35]. Conversely, older adults can also demonstrate decreased sensitivity to some drugs, such as a weakened cardiac response to β-agonists like dobutamine due to changes in β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity [35]. These PD changes, combined with PK alterations, significantly increase the vulnerability of older adults to adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Drug-Drug and Drug-Lifestyle Interactions

Polypharmacy as a Prevalent Risk Factor

Polypharmacy, commonly defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications, is a global healthcare concern, especially among the elderly [36]. It poses significant challenges, leading to "medication non-adherence, increased risk of drug duplication, drug–drug interactions, and adverse drug reactions (ADRs)" [36]. ADRs are a leading cause of mortality in developed countries, and polypharmacy is a key contributor to this risk. A study analyzing 483 primarily elderly and polymedicated patients found that the most frequently prescribed drug classes included antihypertensives, platelet aggregation inhibitors, cholesterol-lowering drugs, and gastroprotective agents [36]. The complex medication regimens increase the probability of interactions, which can be pharmacokinetic (affecting drug levels) or pharmacodynamic (affecting drug actions).

The Role of Lifestyle Factors

Lifestyle factors, including diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise, and sleep, are recognized modifiable contributors to biological aging and drug response variability [37]. These factors can directly and indirectly influence drug efficacy and safety. For example, dietary components can inhibit or induce drug-metabolizing enzymes, while smoking can induce CYP1A2 activity, increasing the clearance of certain drugs [36]. A large longitudinal cohort study in Southwest China demonstrated that healthy lifestyle changes, particularly improvements in diet and smoking cessation, were inversely associated with accelerated biological aging across multiple organ systems [37]. The study found that diet was the major contributor to slowing comprehensive biological aging (24%), while smoking cessation had the greatest impact on slowing metabolic aging (55%) [37]. This underscores the powerful role lifestyle plays in modulating an individual's physiological state and, consequently, their response to pharmacotherapy.

Methodologies for Studying Non-Genetic Variability

Population Pharmacokinetic (PopPK) Modeling

To quantify and account for variability in drug exposure, researchers employ population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) methods. Unlike traditional PK analyses that require dense sampling from each individual, PopPK uses sparse data collected from a population of patients to identify and quantify sources of variability [38]. The standard approach is Non-linear Mixed Effects Modeling (NONMEM), which involves:

- Developing a Structural Model: A model that best describes the absorption, distribution, and elimination of the drug, characterizing the population mean concentration-time curve [38].

- Identifying Covariates: Systematic exploration of patient factors (covariates) that explain variability in PK parameters. Covariates examined typically include age, body size, and measures of renal and hepatic function [38].

- Quantifying Random Variability: The model distinguishes between inter-individual variability (IIV), inter-occasion variability, and residual unexplained variability [38] [39].

This approach allows for the development of models that can predict drug exposure in individuals with specific demographic and physiological characteristics.

Advanced Preclinical Models

Incorporating patient diversity early in drug development is crucial for predicting clinical outcomes. Advanced preclinical models, such as 3D microtissues derived from a range of human donors, are being used to address this need [40]. Unlike traditional 2D cell cultures or animal models, these platforms can maintain key physiological features and be produced using cells from multiple individuals with unique genetic and metabolic profiles [40]. This capability enables drug developers to:

- Uncover inter-individual variability in drug response and toxicity.

- De-risk clinical trials by providing a clearer picture of how a drug might perform in diverse populations.

- Tailor therapies for personalized medicine by evaluating biomarkers and other factors relevant to patient stratification [40].

Bioequivalence and Interchangeability

When evaluating generic drugs or new formulations, bioequivalence studies are critical. The concept extends beyond simple average bioequivalence, which only compares average bioavailability [41]. To fully assess interchangeability, more robust methods are used:

- Population Bioequivalence: Assesses the total variability of the bioavailability measure in the population, ensuring that a prescriber can confidently choose either the test or reference product for a new patient [41].

- Individual Bioequivalence: Assesses within-subject variability for the test and reference products, ensuring that a patient can be safely switched from one product to another [41]. These statistical approaches ensure that not only the average exposure but also the variability in exposure is comparable between products, safeguarding therapeutic equivalence across a diverse patient population.

Experimental Data and Supporting Evidence

Quantitative Data on Drug Utilization and Interactions

Data from a study of 483 elderly, polymedicated patients provides concrete evidence of the complex medication landscape in this population. Table 2 lists the most frequently used drug classes and their prevalence, highlighting the high potential for drug-drug interactions [36].

Table 2: Most Frequently Used Drug Classes in an Elderly Polymedicated Cohort (n=483) [36]

| Drug/Treatment Class | Frequency of Use (%) | Male Frequency of Use (%) | Female Frequency of Use (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antihypertensives | 72.26% | 78.60% | 67.16% |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors/anticoagulants | 65.84% | 68.37% | 63.81% |

| Cholesterol-lowering drugs | 55.49% | 56.74% | 54.48% |

| Gastroprotective agents | 52.17% | 50.23% | 53.73% |

| Sleep disorder treatment | 34.78% | 24.19% | 43.28% |

| Diuretics | 32.92% | 32.56% | 33.21% |

| Analgesics | 32.30% | 22.33% | 40.30% |

| Anxiolytics | 30.85% | 20.47% | 39.18% |

The same study also analyzed drug-lifestyle interactions, finding that these primarily involved inhibitions but also included inductions of metabolic pathways, with significant differences observed when analyzed by gender [36].

Protocol for PopPK Analysis

A detailed protocol for conducting a PopPK analysis to estimate within-subject variability (WSV) using single-period clinical trial data is as follows [39]:

- Data Collection: Administer the drug of interest to a cohort of subjects (≥18 subjects recommended for reliable estimation) and collect plasma samples at scheduled time points.

- Bioanalytical Assay: Quantify drug concentrations in the plasma samples using a validated method (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to ensure data quality and minimize assay-related variability.

- Model Development: Using NONMEM software:

- Input the concentration-time data for all subjects.

- Develop a structural PK model (e.g., one- or two-compartment) to describe the drug's disposition.

- Estimate the fixed effects (typical PK parameters like clearance and volume of distribution) and random effects (IIV and residual variability).

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model's performance using diagnostic plots and statistical criteria. The estimated residual variability (RV) in a well-controlled study approximates the WSV.

- Data Application: The estimated WSV can then be used for more accurate sample size calculation in future clinical trials, ensuring they are neither underpowered nor ethically and economically inefficient due to excessive subject numbers [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Non-Genetic Variability

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Population PK Software (e.g., NONMEM) | The industry standard for non-linear mixed-effects modeling, used to perform PopPK analyses and quantify IIV and RV from sparse clinical data [38] [39]. |

| 3D In Vitro Microtissue Platforms | Physiologically relevant models derived from primary human cells from multiple donors; used to assess inter-individual variability in drug response, metabolism, and toxicity during preclinical development [40]. |

| Validated Bioanalytical Assays (e.g., LC-MS/MS) | Essential for the accurate quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological fluids (plasma, serum), providing the high-quality data required for PK and PopPK analyses [39]. |

| Clinical Data Management System | Secure software for managing and integrating complex clinical trial data, including demographic information, laboratory values, medication records, and PK sampling times. |

| Cocktail Probe Substrates | A set of specific drugs each metabolized by a distinct enzyme pathway; administered to subjects to simultaneously phenotype multiple drug-metabolizing enzyme activities in vivo. |

Integrated Pathways of Non-Genetic Variability

The following diagram synthesizes the interconnected pathways through which non-genetic factors contribute to variability in individual drug response, framing it within the conflict between population mean and individual patient needs.

Diagram: Pathways Linking Non-Genetic Factors to Variable Drug Response. The diagram illustrates how non-genetic factors create variability from the population mean, necessitating precision medicine approaches.

The journey from population-based dosing to truly individualized therapy requires a deep understanding of non-genetic sources of variability. Age-related physiological changes, declining organ function, complex drug interactions, and modifiable lifestyle factors collectively exert a powerful influence on drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, often overshadowing the "average" profile derived from clinical trials. Tackling this complexity demands robust methodological tools—such as population PK modeling, advanced in vitro systems, and comprehensive bioequivalence assessments—that can quantify and integrate these factors. By systematically accounting for the contributors outlined in this guide, researchers and drug developers can better navigate the gap between the population mean and the individual patient, ultimately paving the way for safer and more effective personalized medicines.

Quantifying Variability: From Population PK to Machine Learning

Pharmacokinetics (PK), the study of how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and eliminates drugs, is fundamental to drug development and precision medicine. Two primary methodological approaches exist for conducting PK analysis: Individual PK and Population PK (PopPK). These approaches represent fundamentally different paradigms for understanding drug behavior. Individual PK focuses on deriving intensive concentration-time profiles and precise PK parameters for single subjects, typically through controlled studies with rich data collection [42] [43]. In contrast, Population PK studies variability in drug concentrations across a patient population using mathematical models, often from sparse, clinically realistic data, to identify and quantify sources of variability such as weight, age, or renal function [29] [44]. This analysis objectively compares these methodologies, framing the discussion within the broader scientific thesis of understanding population averages versus individual variation—a central challenge in pharmacological research and therapeutic individualization.

Core Methodological Differences

The distinction between Individual and Population PK extends beyond mere application to fundamental differences in data requirements, analytical frameworks, and underlying goals.

Foundational Principles and Data Requirements

- Individual PK often employs noncompartmental analysis (NCA), a model-independent approach that provides a direct description of the data, or compartmental analysis, which fits exponential equations to individual concentration-time data [42]. It requires rich, intensive sampling from each subject, with many samples collected at fixed intervals to fully characterize the drug's time-course [29] [44].

- Population PK uses nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) modelling [45]. This approach simultaneously analyzes data from all individuals in a population. Its power lies in handling sparse data (only a few samples per patient) collected from unstructured dosing and sampling schedules, as is common in later-phase clinical trials or studies in vulnerable populations [29] [44].

Analytical Outputs and Interpretability

The outputs of these analyses also differ significantly, as summarized in Table 1.

- Individual PK Outputs: The primary results are specific PK parameters for each individual, such as maximum concentration (C~max~), area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), clearance (CL), and terminal half-life (t~1/2~) [42]. These are direct, intuitive measures of drug exposure.

- Population PK Outputs: The results include estimates of the typical (population average) value for each PK parameter (e.g., typical clearance), covariate effects (quantifying how patient characteristics like weight or renal function influence PK), and estimates of variability [29] [45]. This includes Between-Subject Variability (BSV) and Residual Unexplained Variability (RUV) [44]. This makes PopPK highly explanatory for variability but also more complex to interpret.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Individual vs. Population Pharmacokinetic Methods

| Feature | Individual PK | Population PK |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Intensive profile of a single subject | Variability in drug concentrations across a population [29] |

| Common Analysis Methods | Noncompartmental Analysis (NCA); One-/Two-compartment models [42] | Nonlinear Mixed-Effects (NLME) Modelling [45] |

| Data Requirements | Rich data (intensive sampling) [43] [44] | Sparse data (few samples per subject) acceptable [43] [44] |

| Handling of Covariates | Not directly integrated; requires subgroup analysis | Directly models effects of covariates (e.g., weight, age, renal function) [29] [44] |

| Key Outputs | C~max~, AUC, CL, V~d~, t~1/2~ for an individual [42] | Typical population parameters, covariate effects, estimates of variability (BSV, RUV) [45] [44] |

| Predictive & Simulative Utility | Limited to simulated profiles for a single, similar individual [42] | High; can simulate outcomes for diverse populations and novel dosing regimens [42] [43] |

| Primary Application Context | Early-phase clinical trials (Phase I), bioavailability/bioequivalence studies [42] [43] | Late-phase clinical trials (Phases II-IV), special populations, model-informed drug development (MIDD) [43] [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis Workflows

Protocol for a Traditional Individual PK Study

A typical Individual PK study, such as a Phase I clinical pharmacology trial, follows a highly structured protocol.

- Study Design: A fixed-dose, parallel-group or crossover design is used. Subjects are healthy volunteers or carefully selected patients.

- Dosing and Sampling: A precise dose is administered, and blood samples are collected at pre-specified, frequent time points (e.g., pre-dose, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours post-dose) to capture the complete concentration-time profile [29].

- Bioanalysis: Plasma or serum samples are analyzed using validated analytical methods (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to determine drug concentrations.

- Data Analysis:

- NCA: Concentrations are plotted against time. PK parameters are calculated directly using trapezoidal rule (for AUC), and observed C~max~ and t~max~ [42].

- Compartmental Analysis: Concentration-time data for each subject is fit to one-, two-, or three-compartment models using software like Phoenix WinNonlin. The model with the best statistical fit (e.g., lowest Akaike Information Criterion) is selected for each individual [42] [45].

Protocol for a Population PK Analysis

Population PK analysis is an iterative process of model development and evaluation, as outlined in the workflow below. It often uses pooled data from multiple studies [43] [44].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing and evaluating a population pharmacokinetic model. (VPC: Visual Predictive Check; BSV: Between-Subject Variability; RUV: Residual Unexplained Variability)

The key steps involve:

- Data Assembly: Data from Phase 2/3 trials or therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is pooled. This includes drug concentrations, dosing histories, and patient covariates [44].

- Structural Model Development: A base PK model (e.g., one- or two-compartment) is built using NLME software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix) to describe the typical concentration-time profile in the population [45] [46].

- Statistical Model Development: Inter-individual variability (IIV) and residual error (RUV) models are added to account for random variability not explained by the structural model [45] [44].

- Covariate Model Development: Covariates (e.g., body size, organ function) are tested for their influence on PK parameters to explain IIV. This is often done using stepwise forward addition/backward elimination, where a change in the objective function value (OFV) of >3.84 (p<0.05) for adding one parameter is considered statistically significant [45] [46].

- Model Evaluation: The final model is rigorously evaluated using goodness-of-fit plots, prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPC), and bootstrap methods [47] [45].

- Simulation: The qualified model is used to simulate drug exposure for various subpopulations and dosing scenarios to inform dosing recommendations [43] [44].

Supporting Experimental Data and Case Studies

Quantitative Evidence from Comparative Studies

Recent research provides quantitative data supporting the application and performance of these methods. A 2025 study by El Hassani et al. directly investigated the impact of sample size on PopPK model evaluation. Using a small real-world dataset from 13 elderly patients receiving piperacillin/tazobactam and a large virtual dataset of 1000 patients, they found that small clinical datasets produced consistent model evaluation results compared to large virtual datasets. Specifically, the bias and imprecision for the Hemmersbach-Miller model were -37.8% and 43.2% (population) for the clinical dataset, versus -28.4% and 40.2% for the simulated dataset, with no significant difference in prediction error distributions [47]. This validates that small, clinically sourced datasets can be robust for external PopPK model evaluation, a key advantage of the approach.

Another 2025 study compared a novel Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) approach with traditional PopPK and classical machine learning for predicting drug concentrations. The results, summarized in Table 2, show that the performance of methods can be context-dependent. For the drug 5FU, the MMPK-SciML approach provided more accurate predictions than traditional PopPK, whereas for sunitinib, PopPK was slightly more accurate [48]. This highlights that while new methods are emerging, PopPK remains a powerful and robust standard.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PK Modeling Approaches from a 2025 Study [48]

| Drug | Modeling Approach | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) | Population PK (PopPK) | Less accurate predictions than SciML |

| 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) | Scientific Machine Learning (MMPK-SciML) | More accurate predictions than PopPK |

| Sunitinib | Population PK (PopPK) | Slightly more accurate predictions than SciML |

| Sunitinib | Scientific Machine Learning (MMPK-SciML) | Slightly less accurate predictions than PopPK |

Application in Biosimilar Development

PopPK/PD modeling is critical in developing biologic drugs and biosimilars. A 2025 PopPK/PD analysis of the denosumab biosimilar SB16 used a two-compartment model with target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) to characterize its PK profile. An indirect response model captured its effect on lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD). The analysis conclusively showed that body weight accounted for 45% of the variability in drug exposure, but this translated to a clinically meaningless change of less than 2% in BMD [46]. Furthermore, the treatment group (SB16 vs. reference product) was not a significant covariate, successfully demonstrating biosimilarity and supporting regulatory approval. This case exemplifies how PopPK/PD moves beyond simple bioequivalence to build a comprehensive understanding of a drug's behavior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful execution of PK studies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and software solutions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Software Tools

| Tool Category | Example Products/Assays | Function in PK Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Bioanalytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry), ECLIA (Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay) [46] | Quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological matrices (e.g., plasma, serum) with high sensitivity and specificity. |

| Population PK Software | NONMEM [49], Monolix Suite [46], Phoenix NLME [42] | Industry-standard NLME modeling software for PopPK model development, estimation, and simulation. |

| Individual PK / NCA Software | Phoenix WinNonlin, R/Python packages | Performing noncompartmental analysis and individual compartmental model fitting. |

| Machine Learning & Automation Tools | pyDarwin [49] | Frameworks for automating PopPK model development using machine learning algorithms like Bayesian optimization. |

The choice between Individual and Population PK is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application, reflecting the necessary balance between understanding central tendencies and individual variations in pharmacology. Individual PK, with its intensive sampling and model-independent NCA, provides the definitive gold standard for characterizing a drug's baseline PK profile in highly controlled settings, making it indispensable for early-phase trials and bioequivalence studies [42]. Population PK, leveraging sparse data and powerful NLME modeling, excels at explaining variability and predicting outcomes in diverse, real-world populations, making it a cornerstone of late-stage drug development, precision dosing, and regulatory submission [43] [29] [44].

The evolution of the field points toward greater integration and automation. Emerging approaches like Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) show promise in enhancing predictive accuracy, sometimes surpassing traditional PopPK [48]. Furthermore, the automation of PopPK model development using frameworks like pyDarwin can drastically reduce manual effort and timelines while improving reproducibility [49]. For researchers and drug developers, a synergistic strategy that utilizes Individual PK for foundational profiling and Population PK for comprehensive characterization and simulation across the development lifecycle is paramount for efficiently delivering safe and effective personalized therapies.

Leveraging Sparse and Intensive Sampling Designs in Population PK Studies

In pharmacometrics, a fundamental tension exists between characterizing the population mean and understanding individual variation. This dichotomy directly influences the choice of pharmacokinetic (PK) sampling strategy. Intensive sampling designs, which collect numerous blood samples per subject, traditionally provide the gold standard for estimating PK parameters in individuals but are often impractical in clinical settings. In contrast, sparse sampling designs, which collect limited samples from each subject but across a larger population, leverage population modeling approaches to characterize both population means and inter-individual variability [50] [51]. The core challenge lies in determining how much information can be reliably extracted from sparse data without compromising parameter accuracy. Population modeling using non-linear mixed-effects (NLME) methods can disentangle population tendencies from individual-specific characteristics, making sparse sampling a viable approach for studying drugs in real-world patient populations where intensive sampling is ethically or logistically challenging [52]. This guide objectively compares these competing approaches, examining their performance, applications, and limitations within modern drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Sampling Design Performance