Beyond the Population Mean: Individual Predictability Differences in Wildlife Behavior and Its Implications for Research

This article synthesizes current research on individual predictability differences in wildlife, moving beyond the study of average population behaviors to explore consistent variations in intraindividual behavioral variation (IIV).

Beyond the Population Mean: Individual Predictability Differences in Wildlife Behavior and Its Implications for Research

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on individual predictability differences in wildlife, moving beyond the study of average population behaviors to explore consistent variations in intraindividual behavioral variation (IIV). For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational concepts of animal personality and behavioral predictability, methodological approaches for quantifying these differences from movement and behavioral data, troubleshooting for common data collection and analysis challenges, and validation through selective breeding and heritability studies. The article highlights how understanding this axis of individual variation can refine animal models, improve experimental design, and inform translational research in biomedicine.

Animal Personality and the Spectrum of Predictability: Why Individual Variation Matters

In the field of behavioral ecology, understanding consistent patterns of individual behavior is crucial for research in wildlife biology and drug development. While early research focused on population-level averages, a paradigm shift has occurred toward recognizing that individual differences are not merely statistical noise but biologically significant phenomena. This guide objectively compares three foundational concepts shaping modern behavioral research: Animal Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, and Intraindividual Variability (IIV). Each represents a different aspect of behavioral variation with distinct methodological requirements and implications for predictability in wildlife studies.

Conceptual Definitions and Comparative Framework

Core Definitions

Animal Personality: Consistent differences in behavior between individuals across time and/or contexts [1] [2]. These are measured as the variance of a random intercept in mixed-effects models, with the existence and extent of among-individual variation quantified as repeatability (R) [1]. For example, individual marmosets show consistent differences in traits like Boldness-Shyness and Exploration-Avoidance [3].

Behavioral Plasticity: The ability of an individual to adjust its behavior in response to changing environmental conditions [4] [1]. This represents reversible behavioral change and is measured as the random slope of a reaction norm in random regression models [1]. Between-individual differences in behavioral plasticity mean that some individuals are more responsive to environmental gradients than others [5].

Intraindividual Variability (IIV): The residual within-individual variability in behavior that remains after accounting for an individual's average behavior (personality) and its reversible plasticity [6] [1]. Also termed "unpredictability," IIV represents consistent differences in how variable individuals are around their own mean behavior [6] [7]. Some individuals are inherently more predictable in their behavior than others, independent of their behavioral type [6].

Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the key characteristics that differentiate these three concepts:

Table 1: Comparative Framework of Key Behavioral Concepts

| Aspect | Animal Personality | Behavioral Plasticity | Intraindividual Variability (IIV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Consistent between-individual differences in average behavioral expression [1] [2] | Within-individual adjustment to environmental changes [4] [1] | Residual within-individual variability around the behavioral mean [6] [7] |

| Primary Focus | Differences between individuals | Changes within individuals | Variability within individuals |

| Temporal Perspective | Consistency across time and contexts | Responsiveness across conditions | Moment-to-moment unpredictability |

| Statistical Representation | Random intercept variance in mixed models | Random slope variance in reaction norms | Residual variance after accounting for mean and plasticity [6] |

| Key Metric | Repeatability (R) | Plasticity coefficient/slope | Intraindividual standard deviation [7] |

| Biological Interpretation | Behavioral type | Flexibility/responsiveness | Predictability/unpredictability [6] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Standardized Testing Protocols

Robust assessment of animal personality, plasticity, and IIV requires specific methodological approaches with repeated measures at their core.

Behavioral Testing Batteries: Multiple tests conducted across different contexts and times are essential. For animal personality assessment, tests should be designed to measure major traits including activity, exploration, boldness, aggressiveness, and sociability [2]. In free-ranging dogs, strong agreement was found between experimental testing and naturalistic observations for human-directed sociability and exploration, supporting method validity [8].

Repeated Measures Design: The fundamental requirement for partitioning behavioral variance. For reliable estimates, researchers should collect 5-10 repeated measures per individual across relevant temporal scales. In mosquitofish, approximately 20 observations per fish across 132 days demonstrated repeatable individual differences in predictability [6].

Cross-Context Validation: Combining experimental manipulations with naturalistic observations. In free-ranging dog studies, researchers assessed "cross-context validity" by comparing behavior in standardized tests with observations of spontaneous behavior in natural environments [8].

Statistical Framework for Variance Partitioning

The quantitative separation of personality, plasticity, and IVI requires specific statistical approaches:

Mixed-Effects Modeling: Using random intercept models to estimate among-individual variance (personality) and within-individual variance [1]. The repeatability (R) is calculated as R = Vamong / (Vamong + Vwithin), where Vamong is among-individual variance and Vwithin is within-individual variance [1].

Random Regression Models: Extending mixed models to include random slopes for environmental gradients enables quantification of individual differences in behavioral plasticity [1]. This approach models how individuals differ in their responsiveness to environmental variables.

IIV Quantification: Calculating the intraindividual standard deviation (iSD) or modeling residual variance heterogeneity [7]. After accounting for individual means and plasticity, the remaining within-individual variability represents IIV, which can itself vary consistently between individuals [6].

Table 2: Experimental Designs for Behavioral Concept Measurement

| Concept | Minimum Repeated Measures | Key Experimental Requirements | Statistical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Personality | 5-10 per individual across contexts [6] [2] | Standardized tests across time and situations | Repeatability estimate (R) with confidence intervals [2] |

| Behavioral Plasticity | Multiple measures across environmental gradient | Experimental manipulation of relevant environmental factors | Significant random slope variance in reaction norms [4] |

| Intraindividual Variability (IIV) | 10+ measures per individual [6] | Control of systematic temporal variation | Repeatability of intraindividual variance [6] |

Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Empirical Effect Sizes Across Taxa

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from empirical studies across different species:

Table 3: Empirical Effect Sizes Across Taxonomic Groups

| Species | Behavioral Trait | Repeatability (Personality) | Plasticity Pattern | IIV Relationship | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitofish | Activity | Significant individual means | Adjusted for temperature response | Repeatable individual differences (IIV) | [6] |

| Jumping Spiders | Activity level | R = 0.449 | Not specified | Positively correlated with mass gain from prey | [9] |

| Common Marmosets | Learning speed | Consistent inter-individual differences | Not specified | Not measured | [3] |

| Free-ranging Dogs | Sociability, Exploration | Not quantified | Context-dependent responses | Not measured | [8] |

| African Elephants | Movement behaviors | Significant individual means | Individual differences in adjustment rates | Individual differences in predictability | [1] |

Fitness and Ecological Consequences

Research has revealed important fitness consequences associated with each behavioral dimension:

Animal Personality: Boldness and exploration traits can affect survival, reproduction, and dispersal success [2]. In conservation contexts, personality influences vulnerability to trapping, with bolder animals being more easily captured [2].

Behavioral Plasticity: Individual differences in plasticity affect how animals respond to environmental change, including human-induced rapid environmental change [5]. The ability to adjust behavior appropriately to changing conditions often enhances fitness.

Intraindividual Variability: IIV has demonstrated mixed fitness relationships across studies. In jumping spiders, activity level IIV positively predicted mass gain from prey but not the number of prey killed [9]. Individual-based models suggest that stochastic environmental variation can maintain IIV in populations even when the optimal strategy has no IIV [7].

Conceptual Relationships and Integration

Integrated Behavioral Framework

The relationship between personality, plasticity, and IIV can be visualized as components of a comprehensive behavioral phenotype:

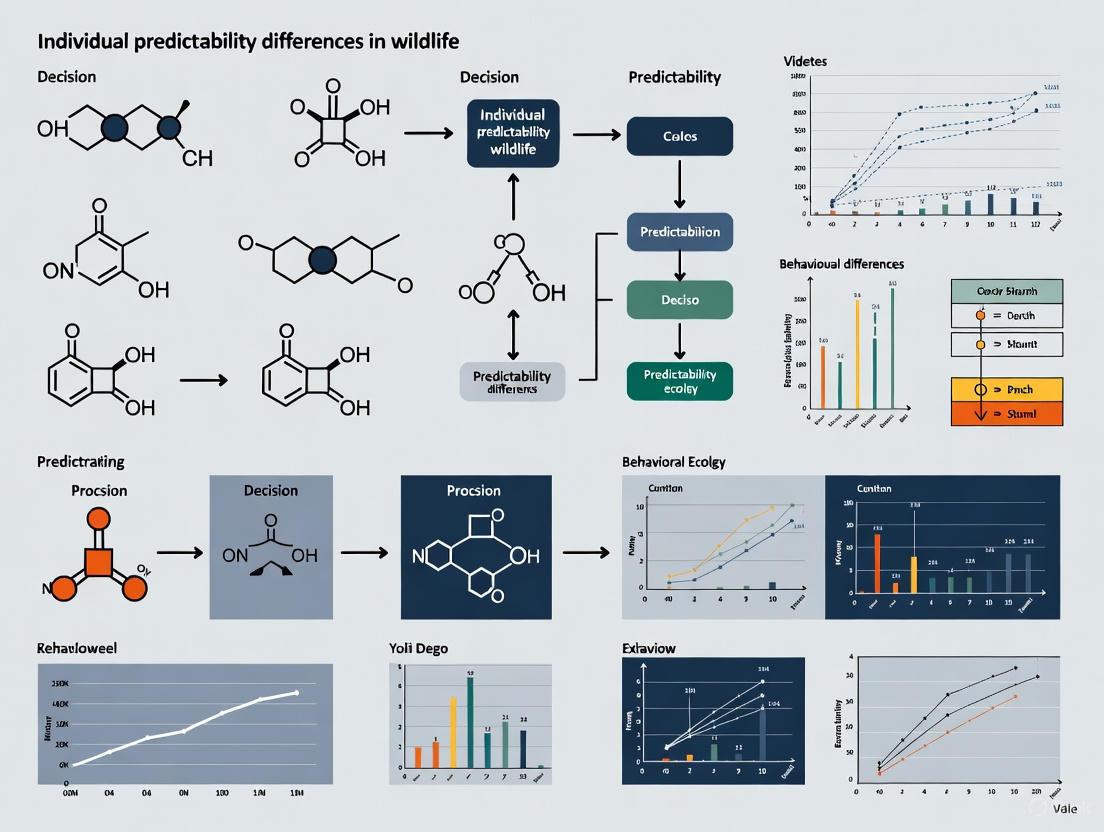

Figure 1: Integrated Framework of Behavioral Components

Methodological Workflow

The experimental and analytical process for quantifying these behavioral components follows a systematic workflow:

Figure 2: Methodological Workflow for Behavioral Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful investigation of animal personality, plasticity, and IIV requires specific methodological tools and approaches:

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Methodologies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Coding Software | BORIS, EthoVision | Automated tracking and behavioral annotation | Enables high-throughput data collection for repeated measures [1] |

| Statistical Environments | R with packages: lme4, MCMCglmm, rptR | Variance partitioning and mixed modeling | Essential for quantifying personality, plasticity, and IIV [1] |

| Field Assessment Tools | C-BARQ (Canine Behavioral Assessment) [10], standardized test batteries | Standardized behavioral assessment across contexts | Enables cross-population comparisons; validated protocols available [8] [10] |

| Tracking Technology | GPS loggers, accelerometers, biologging devices | Continuous monitoring of movement and activity | Provides naturalistic behavioral data at fine temporal scales [1] |

| Experimental Arenas | Open field tests, novel object tests, maze designs | Controlled behavioral testing | Must be validated for target species and ecological relevance [2] |

Animal personality, behavioral plasticity, and intraindividual variability represent complementary rather than competing frameworks for understanding individual differences in behavior. Personality provides the consistent baseline, plasticity enables adaptive responsiveness, and IIV contributes to unpredictability with potential fitness benefits. Research designs that simultaneously quantify all three components through repeated measures, environmental monitoring, and appropriate statistical modeling will provide the most comprehensive understanding of individual behavioral variation. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for conservation applications [2], wildlife management [1], and understanding how individuals respond to environmental change [5].

Recent research has established that consistent differences in intraindividual variability (IIV) represent a stable personality trait in animals, termed "predictability." This article examines the foundational evidence for this trait, drawing on key studies in animal behavior and exploring the methodological parallels in human personality assessment. We compare the empirical approaches used in wildlife research with emerging, objective methods in human studies, such as gait-based personality assessment. The synthesis of these findings underscores that predictability itself varies consistently between individuals and has implications for ecological adaptation and potential translational applications in fields like psychopharmacology and drug development.

Personality psychology has traditionally focused on consistent individual differences in average behavioral tendencies. However, a revolutionary perspective posits that the pattern of behavioral variation itself can be a stable trait. This trait, "predictability," refers to consistent between-individual differences in within-individual behavioral variation (IIV). In simpler terms, some individuals are inherently more consistent in their behavior from moment to moment, while others are more variable, and this difference is a reliable characteristic of the individual.

This concept forces a re-evaluation of behavioral consistency. The pursuit of consistency in social behavior has historically followed two major routes: one that aggregates data across situations to identify stable individual differences, and another that assesses consistency from situation to situation, focusing on the discriminativeness of behavior [11]. The study of IIV as a personality trait bridges these routes by treating an individual's pattern of variability as a stable, measurable characteristic. Initially explored in wildlife research, this concept is now gaining traction in human studies, supported by technological advances in objective measurement and modeling.

Key Evidence from Wildlife and Human Research

The following table summarizes the core quantitative findings from pivotal studies investigating IIV and predictability across different species and methodologies.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on Behavioral Predictability and IIV

| Study Focus | Species/Subjects | Key Quantitative Finding | Context/Duration | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictability as a Trait [6] | 30 adult male mosquitofish | Repeatability for IIV (( R = .47 )) was evident after accounting for activity trends. | Multiple observations over 132 days | First evidence that predictability is a repeatable characteristic of individual animals. |

| Personality & Job Performance [12] | 288 professionals | Intra-individual variability in Neuroticism was predictive of some job performance criteria. | Work and non-work contexts; supervisor ratings | Demonstrates that IIV in specific traits (e.g., Neuroticism) has real-world consequences in humans. |

| Gait-Based Assessment [13] | 152 human adults | Machine learning models (GPR, LR) showed high criterion validity (~0.49) and split-half reliability (>0.8) for personality assessment. | Single session with BFI-44 scale | Provides an objective, non-invasive method to assess stable personality traits, supporting the measurability of consistent patterns. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Foundational Wildlife Experiment: Mosquitofish Activity

The seminal study on predictability as a personality trait was conducted on mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki), providing a rigorous experimental protocol for quantifying IIV [6].

- Subjects and Housing: 30 adult male mosquitofish were housed individually to control for social influences on behavior.

- Behavioral Assay: The undisturbed activity of each fish was repeatedly scored in a standardized environment. The core of the protocol was the multiple observation bouts across a long temporal scale (132 days), with each fish being observed approximately 15 times.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantifying IIV: For each fish, the within-individual variation in activity was calculated across the multiple observation bouts.

- Accounting for Confounds: The analysis statistically controlled for individual differences in long-term activity trends and for individual plasticity in response to fine-scale temperature variation. This was crucial to isolate "unpredictability" from systematic changes.

- Assessing Repeatability: The repeatability (( R )) of the IIV metric was calculated. A significant repeatability of .47 indicated that nearly half of the variance in predictability was due to stable differences between individuals, confirming it as a personality trait.

Advanced Human Experiment: Gait-Based Personality Assessment

A modern approach in human research uses gait analysis to establish objective personality assessment models, reflecting the stability of traits [13].

- Participants: 152 adults without mental illness or physical disability.

- Data Collection:

- Gait Recording: Participants walked back and forth for 2 minutes in a 6m x 2m area under normal conditions. Their gait was recorded using a standard 2D camera.

- Personality Baseline: Immediately after, participants completed the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI-44) to provide self-reported trait scores for Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness.

- Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering:

- Skeleton Extraction: OpenPose software was used to extract the 2D coordinates of 25 body key points from each video frame.

- Data Unification: Only the front-view gait cycles were retained. The data for each participant was unified to 75 frames to standardize input.

- Coordinate Translation: The coordinate system was translated to set the MidHip joint as the origin, reducing the influence of body shape and absolute position, and highlighting the periodicity of movement.

- Feature Construction: A diverse set of static and dynamic features was built based on skeleton coordinates, inter-frame differences, distances between joints, angles between joints, and wavelet decomposition coefficients.

- Modeling and Validation: Multidimensional personality trait assessment models were established using machine learning algorithms (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression, Linear Regression). The models were evaluated for:

- Criterion Validity: Correlation between model-predicted trait scores and the BFI-44 scores (mean ~0.49).

- Split-half Reliability: Correlation between predictions from two halves of the gait data (mean >0.8).

- Convergent and Discriminant Validity: Showing the model correctly correlated related measures and distinguished between distinct traits.

This table details key materials and computational tools used in the featured human gait analysis study, which can serve as a template for designing similar research on behavioral predictability [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Gait-Based Personality Assessment

| Item Name | Function/Description | Specific Use in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Standard 2D Camera | Video recording of participant gait. | To capture raw behavioral data (walking) in a standardized environment. |

| OpenPose Software | Human posture recognition system. | To extract 2D skeletal coordinates (25 key points) from gait videos automatically. |

| Big Five Inventory-44 (BFI-44) | Self-report personality questionnaire. | To provide ground truth data for the five major personality traits for model training and validation. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Model | A machine learning algorithm. | To establish the primary predictive model mapping gait features to personality trait scores. |

| Coordinate Translation Algorithm | Custom script for data processing. | To re-center skeletal data around the MidHip joint, emphasizing movement over position. |

| Wavelet Decomposition | Signal processing technique. | To construct dynamic time-frequency features from the skeletal coordinate sequences. |

Visualizing Workflows and Conceptual Frameworks

Experimental Workflow for Gait-Based Assessment

The diagram below outlines the end-to-end process for assessing personality traits from gait video, as described in the research [13].

Conceptual Framework of Predictability as a Trait

This diagram illustrates the core conceptual model of predictability derived from consistent differences in Intraindividual Variation (IIV), integrating evidence from both animal and human studies [6] [12].

The evidence from wildlife and human research converges to solidly establish predictability as a valid personality trait. The finding that IIV is itself a stable, repeatable characteristic adds a crucial dimension to the understanding of individual differences. This has profound implications for behavioral ecology, where predictability may influence survival and reproductive strategies, and for translational fields like drug development. In pharmacology, for instance, Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) could incorporate individual differences in behavioral predictability to create more sophisticated "virtual population simulations," improving the prediction of drug efficacy and side effects [14]. Future research should focus on elucidating the neural and genetic correlates of this trait and further developing non-invasive, objective methods for its measurement across species.

Moving Beyond the 'General Public' and Population Means in Study Design

In both wildlife research and preclinical drug development, the traditional reliance on population-level averages has often obscured critical, biologically significant variation at the individual level. The "general public" paradigm in wildlife management, which treats populations as homogenous units, parallels the use of completely randomized designs in laboratory science that can be confounded by cage effects and ignore individual phenotypic plasticity [15] [16]. A shift toward studying individual predictability—the consistent differences in how individuals vary from their own mean behavior—is providing new insights for conservation biology, toxicology, and pharmaceutical development. This paradigm change recognizes that individuals within a population may exhibit specialized behavioral niches, differing not only in their average traits but also in their responsiveness to environmental change and inherent behavioral variability [1].

The failure to account for this individual variation carries significant consequences. In laboratory animal experiments, flawed experimental designs that fail to control for cage effects and misidentify the correct unit of analysis have been shown to introduce bias, increase false positive rates, and squander resources [16]. Similarly, in wildlife studies, focusing solely on population means without considering individual differences can lead to ineffective management policies and an incomplete understanding of species ecology [1] [15]. This guide compares emerging methodologies that address these limitations across research domains, providing experimental data and protocols for implementing more nuanced, individual-focused study designs.

Conceptual Framework: From Population Averages to Individual Variation

The statistical partitioning of behavioral variation provides a framework for moving beyond population means. Behavioral ecology differentiates among several key components of individual variation [1]:

- Animal Personality: Intrinsic, repeatable differences in average behavioral expression among individuals across time and context.

- Behavioral Plasticity: The reversible changes in behavior an individual shows in response to environmental conditions.

- Behavioral Syndrome: A correlation between an individual's average expression of different behaviors.

- Predictability: The residual within-individual variability of behavior around its mean after accounting for average behavior and plasticity.

This framework allows researchers to determine whether observed variation stems from intrinsic differences among individuals or reversible responses to the environment—a distinction crucial for predicting how populations may respond to environmental change, pharmaceutical interventions, or conservation measures [1].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Individual Variation Research

| Concept | Definition | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Personality | Repeatable differences in average behavior among individuals [1] | Individuals may maintain consistent behavioral strategies regardless of population-level trends. |

| Behavioral Plasticity | Individual responsiveness to environmental gradients [1] | Individuals differ in how flexibly they adjust behavior to changing conditions. |

| Behavioral Predictability | Consistency of an individual's behavior around its mean [1] | Some individuals are more variable in their behavior than others, affecting survival risk. |

| Behavioral Syndrome | Correlation between an individual's expression of different behaviors [1] | Interventions affecting one behavior may have unintended consequences on correlated traits. |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | Organism's capacity to produce distinct phenotypes in response to environmental variation [16] | Genetic similarity does not guarantee identical responses to experimental treatments. |

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for partitioning behavioral variation, moving beyond the population mean to individual-level components.

Methodological Comparisons: Approaches for Studying Individual Variation

Wildlife Research Methodologies

Wildlife research has developed several non-invasive approaches to study individual animals in their natural habitats, reducing disturbance while gathering individual-level data [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedigree Reconstruction | Uses genetic samples to reconstruct kinship and infer unsampled individuals [18] | One-time noninvasive genetic sampling of individuals | Efficient for low-density populations; infers "invisible" individuals [18] | Accuracy depends on knowing approximate sampling proportion [18] |

| Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) | Uses repeated sightings of marked individuals to estimate abundance [18] | Multiple sampling occasions; individual identification | Accounts for imperfect detection; well-established methods | Costly for wide-ranging species; requires repeated surveys [18] |

| Variance Partitioning | Statistically decomposes behavioral variation into among-individual and within-individual components [1] | Repeated measures of individual behavior over time | Directly quantifies individual differences and plasticity [1] | Requires substantial longitudinal data on individuals |

| Spatial Capture-Recapture (SCR) | Extends CMR by explicitly incorporating spatial information [18] | Spatial locations of detections plus individual identification | Accounts for spatial heterogeneity in detection | Complex modeling; computationally intensive |

Laboratory Research Methodologies

Laboratory animal experiments require rigorous designs to control for confounding variables while allowing for individual variation assessment.

Table 3: Comparison of Laboratory Experimental Designs

| Design | Key Principle | Unit of Analysis | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completely Randomized Design (CRD) | Random assignment of animals to cages, all animals in cage receive same treatment [16] | Cage (average response of animals within) | Straightforward; controls for cage effect | Increased variability; requires more cages [16] |

| Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) | One animal from each treatment group assigned to each cage (block) [16] | Individual animal | Controls for cage effect; reduces variability | Limited by ethical restrictions on animals per cage [16] |

| Cage-Confounded Design (CCD) | Treatments assigned to entire cages; animal incorrectly used as unit [16] | Animal (incorrect) | Logistically simple; fewer cages required | Completely confounded results; pseudoreplication; biased outcomes [16] |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Pedigree Reconstruction for Abundance Estimation

Protocol Objective: Estimate wildlife population abundance through genetic pedigree reconstruction [18].

Methodology:

- Non-invasive Sampling: Collect genetic material (hair, feces, feathers) systematically across study area.

- Genotype Analysis: Identify unique individuals and their genetic relationships.

- Pedigree Reconstruction: Partition population into four segments:

- Nlinked: Sampled individuals related to other sampled individuals.

- Nunlinked: Sampled individuals unrelated to any other sampled individuals.

- Ninferred: Unsampled individuals inferred through kinship (e.g., parent-offspring relationships where only one parent sampled).

- Ninvisible: Unsampled individuals with no evidence of reproduction.

- Population Estimation: Calculate total abundance as the sum of these four components [18].

Experimental Data: Simulation studies using moose (Alces americanus) populations demonstrate that pedigree reconstruction provides accurate estimates of adult population size and trend, particularly for smaller areas and low-density populations. Novel bootstrapped confidence intervals performed as expected with intensive sampling [18].

Figure 2: Workflow for pedigree reconstruction abundance estimation, showing how unsampled individuals are inferred.

Variance Partitioning for Behavioral Variation

Protocol Objective: Quantify components of behavioral variation using repeated measures of individual behavior [1].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Obtain repeated measurements of movement behaviors (e.g., activity, habitat selection, foraging site fidelity) from tracked individuals over time.

- Mixed-Effects Modeling: Use random regression models to partition variance:

- Among-individual variance: Represented by random intercepts (animal personality).

- Plasticity variance: Represented by random slopes (individual responsiveness to environment).

- Within-individual variance: Residual variation (predictability).

- Repeatability Calculation: Calculate as R = Vamong / (Vamong + V_within), where V represents variance components.

- Behavioral Syndrome Assessment: Correlate individual random intercepts across different behaviors.

Experimental Data: Research on African elephants (Loxodonta africana) demonstrated significant among-individual variation in movement behaviors, with individuals differing in their average behavior, responsiveness to temporal gradients, and behavioral predictability. Furthermore, a behavioral syndrome was identified where farther-moving individuals had shorter mean residence times [1].

Randomized Complete Block Design

Protocol Objective: Control for cage effects while testing multiple treatments in laboratory setting [16].

Methodology:

- Block Formation: Assign one animal from each treatment group to each cage, making each cage a block.

- Randomization: Randomly assign treatments to animals within each block.

- Blinding: Code treatments and blind investigators to group assignments until after statistical analysis.

- Data Analysis: Use two-way ANOVA with treatment and cage as factors of interest.

Experimental Data: Example vaccination challenge study in Syrian hamsters demonstrated proper implementation of RCBD. Sixteen hamsters were housed in four cages with four animals each, and four treatments (PBS control and three vaccine formulations) were randomly assigned to one animal per cage. This design controlled for cage effects while maintaining ethical housing standards [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Individual Variation Studies

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive Genetic Samplers | Collect hair, feathers, feces without disturbing animals [17] | Wildlife pedigree reconstruction; population monitoring |

| Bio-logging Devices | Record continuous data on individual movement and activity [1] | Quantifying individual behavior patterns in natural environments |

| GPS Tracking Systems | Document individual space use and habitat selection over time [1] | Longitudinal studies of individual variation in movement |

| Genetic Microsatellite Panels | Identify individuals and determine kinship relationships [18] | Pedigree reconstruction; relatedness estimation |

| Mixed-Effects Modeling Software | Partition variance into among-individual and within-individual components [1] | Quantifying animal personality and behavioral plasticity |

| Randomized Block Design Protocols | Control for cage effects in laboratory experiments [16] | Ensuring valid statistical inference in preclinical research |

The evidence from both wildlife ecology and laboratory science demonstrates that moving beyond population-level means to consider individual variation produces more accurate, reliable, and biologically meaningful research outcomes. Methodologies such as pedigree reconstruction, variance partitioning, and randomized complete block designs provide robust frameworks for achieving this paradigm shift. By implementing these approaches, researchers can better account for the intrinsic individual differences that significantly influence experimental results, population dynamics, and conservation outcomes. This transition from studying the "general public" to understanding individual variation and predictability represents a fundamental advancement in how we design studies, analyze data, and interpret biological variation across scientific disciplines.

The Ecological and Evolutionary Significance of Behavioral Predictability

Behavioral predictability, defined as the consistency of an individual's behavior around its own average (low intra-individual variability or IIV), represents an emerging axis of animal personality research with profound ecological and evolutionary implications. This article explores behavioral predictability as a measurable trait that varies consistently among individuals, complementing the more traditional focus on mean behavioral tendencies. While behavioral ecology has long recognized that individuals differ in average expression of traits like boldness or aggression, only recently has attention shifted to how individuals also differ in their behavioral variability around these averages [19]. This predictability operates as a distinct aspect of an animal's behavioral syndrome, potentially influencing fitness, ecological interactions, and evolutionary trajectories.

Research across diverse taxa—from barn owls to dairy calves—demonstrates that predictability exhibits consistent between-individual variation, is heritable, and has measurable consequences for survival, space use, and reproductive success [20] [19]. The growing interest in this field reflects an important paradigm shift in behavioral ecology: rather than treating within-individual variation as statistical noise, researchers now recognize it as biologically meaningful data offering unique insights into individual strategies and population dynamics. This article provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches, empirical findings, and methodological frameworks advancing our understanding of behavioral predictability's ecological and evolutionary significance.

Quantitative Comparisons Across Taxa: Empirical Evidence

Behavioral predictability research has yielded quantitatively comparable results across diverse species, revealing patterns in how predictability varies and correlates with ecological outcomes. The table below synthesizes key empirical findings from vertebrate studies:

Table 1: Comparative Empirical Evidence of Behavioral Predictability Across Species

| Species | Behavioral Metric | Research Design | Key Findings on Predictability | Fitness Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barn Owl (Tyto alba) | Nightly maximum displacement | High-resolution GPS tracking (74 individuals, ~115 nights each) [20] | Individuals differed consistently in movement predictability; juveniles less predictable than adults | More predictable individuals had smaller home ranges and lower survival rates |

| Dairy Calf (Bos taurus) | Feeding rate, meal size, total meals | Computerized feeder monitoring (48 calves, 57,196 feeding records) [19] | High between-individual variation in predictability for feeding rate; lower variation for meal size | Predictability measures potentially inform health and welfare monitoring |

| Wild Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | Stress response to shocks | Laboratory stress tests with predictable vs. unpredictable footshocks [21] | No significant differences in motility patterns between predictable and unpredictable stress groups | Limited utility of motility parameters for predictability-based experiments |

| Human (Homo sapiens) | Well-being indicators | Repeated bi-weekly measures of life satisfaction, mental health, stress, loneliness, self-rated health [22] | Substantial within-individual variability across all well-being indicators; females and those with lower baseline well-being showed higher variability | Fluctuations may represent drifting in and out of poor states rather than permanent traits |

The comparative evidence reveals that behavioral predictability functions as an ecologically significant trait across diverse contexts. In barn owls, movement predictability directly impacted survival and space use, demonstrating its fitness consequences [20]. In calves, predictability differences in feeding behaviors highlighted potential applications for precision livestock farming [19]. The human well-being study revealed that emotional states show substantial fluctuations in emerging adulthood, suggesting predictability patterns extend to human psychological domains [22].

Experimental Methodologies: Protocols for Quantifying Predictability

High-Resolution Wildlife Tracking

Research on barn owls exemplifies sophisticated protocols for quantifying movement predictability in wild populations [20]. This methodology involves capturing 92 individuals and fitting them with ATLAS tags that record positional data every few seconds across extensive monitoring periods (averaging 115±112 nights). The experimental workflow follows these key stages:

- Tag Deployment: Fitting owls with lightweight GPS tags using harness designs that minimize behavioral impacts

- Data Collection: Automated tracking via fixed receiver stations that record positional data when tagged owls are within range

- Movement Index Calculation: From raw trajectories, compute nightly maximum displacement (straight-line distance from daytime roost to farthest nightly location)

- Statistical Modeling: Employ double-hierarchical generalized linear mixed models (DHGLM) to simultaneously estimate:

- Individual differences in mean movement (behavioral type)

- Individual differences in intra-individual variability (predictability)

- Cross-Validation: Assess temporal consistency of predictability estimates by comparing across different time periods

- Ecological Correlation: Relate predictability estimates to home range size and survival data

This protocol yields both mean behavioral tendencies (e.g., some individuals consistently range farther than others) and individual predictability metrics (how consistently each individual follows its characteristic ranging pattern) [20].

Automated Behavioral Monitoring in Captive Settings

Calf feeding research demonstrates high-throughput predictability assessment using automated monitoring systems [19]. The experimental protocol includes:

- Subject Management: Holstein Friesian calves (n=48) housed in groups of 16 with computerized milk feeders

- Data Acquisition: RFID-triggered recording of feeding behaviors (57,196 records over 35 days) including:

- Feeding rate (volume consumed per minute)

- Meal size (total volume per feeding bout)

- Total daily meals (number of feeding bouts)

- Multivariate Modeling: Application of multilevel models to partition variance components:

- Between-individual variance (differences in average behavior)

- Within-individual variance (predictability around individual averages)

- Repeatability Calculation: Proportion of total variance explained by between-individual differences

- Predictability Quantification: Coefficient of variation in individual predictability for each behavior

This approach revealed that feeding rate and total meals showed higher between-individual variation and repeatability, while meal size was more homogeneous across individuals [19].

Figure 1: Experimental workflows for quantifying behavioral predictability in wild and captive settings

Conceptual Framework: Predictability in Ecological and Evolutionary Context

Behavioral predictability operates within a conceptual framework that connects individual differences to ecological and evolutionary consequences. The diagram below illustrates the proposed pathways through which predictability influences fitness and population dynamics:

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of behavioral predictability's ecological and evolutionary significance

This framework positions behavioral predictability as arising from genetic, developmental, and neurological factors that influence cognitive control processes [23]. These processes regulate how individuals respond to environmental variation, ultimately affecting ecological interactions like space use and foraging. In barn owls, more predictable individuals established smaller home ranges, potentially reflecting more efficient territory use but also potentially increasing vulnerability if environmental conditions change [20]. The ultimate fitness consequences manifest through survival probability and reproductive success, creating the evolutionary selective pressures that maintain predictability variation within populations.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Technologies

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Behavioral Predictability Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Research Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Systems | ATLAS GPS, RFID networks, Bio-logging tags | High-resolution movement data collection for wild and captive animals [20] [19] | Range, resolution, battery life, data storage, animal burden |

| Automated Monitoring | Computerized feeders, Camera traps, Acoustic sensors | Continuous behavioral recording with minimal human interference [19] | Data management, sensor reliability, environmental durability |

| Statistical Frameworks | Double-hierarchical GLMM, Multilevel modeling, Bayesian methods | Partitioning within- and between-individual variance components [20] [19] | Computational demands, required sample sizes, random effects structure |

| Data Processing | R, Python, specialized movement analysis packages | Trajectory analysis, data cleaning, metric calculation [20] | Reproducibility, automation needs, visualization capabilities |

| Experimental Design | Repeated measures, Balanced sampling, Cross-validation | Establishing temporal consistency of predictability [20] | Logistics, subject availability, time requirements |

This toolkit enables researchers to address core questions about behavioral predictability, including its individual consistency, environmental sensitivity, and ecological impacts. The statistical frameworks are particularly crucial as they move beyond traditional mixed models that treat residual variance as noise, instead modeling it as a biologically interesting outcome [19]. Technological advances in tracking and monitoring now provide the extensive repeated measurements needed to quantify IIV with sufficient precision, opening new avenues for understanding this dimension of animal personality.

Behavioral predictability represents a robust and ecologically significant aspect of animal personality with demonstrated consequences for fitness-relevant outcomes. The comparative evidence presented reveals that predictability varies consistently among individuals across diverse taxa, is influenced by factors like age and experience, and has measurable impacts on survival, space use, and potentially reproductive success. The barn owl findings demonstrating survival consequences of movement predictability offer particularly compelling evidence for its evolutionary significance [20].

Future research should prioritize several key directions:

- Longitudinal Studies: Tracking predictability across life stages to understand developmental trajectories

- Genetic Architecture: Quantifying heritability and genomic foundations of predictability variation

- Neurobiological Mechanisms: Linking predictability to neurological structure and function

- Human Applications: Exploring parallels in human behavioral variability and psychological functioning [22]

- Conservation Implications: Applying predictability metrics to wildlife management and species preservation

As research methodologies continue advancing, particularly through enhanced tracking technologies and sophisticated statistical models, our understanding of behavioral predictability will deepen, potentially transforming how we conceptualize individual differences and their ecological and evolutionary consequences.

Quantifying the Unpredictable: Statistical and Technological Approaches to Measuring IIV

In wildlife research, understanding the evolution and ecology of traits requires dissecting the total observed variation into its constituent parts. Variance partitioning is a powerful statistical approach that isolates among-individual variation (differences between subjects) from within-individual variation (changes within subjects over time or context). This separation is crucial for quantifying individual predictability, behavioral syndromes, and genotype-by-environment interactions. This guide compares the application of this methodology across study systems, detailing experimental protocols, analytical workflows, and key reagents, framed within the broader thesis of individual predictability differences in wildlife research.

A fundamental goal in evolutionary ecology is understanding how selection acts on phenotypic variation. The phenotypic variance (VP) observed in a trait can be partitioned into multiple biological components, primarily:

- VA: Among-individual variance, reflecting consistent differences between individuals.

- VW: Within-individual variance, representing temporal or contextual fluctuation within a single individual.

The sum VP = VA + VW allows calculation of repeatability (R = VA/VP), which sets an upper limit to heritability and measures individual predictability [24] [25]. Isolating VA is essential for understanding evolutionary potential, as this component is the raw material upon which selection acts. Conversely, VW informs about phenotypic plasticity and how individuals respond to changing environments. The extension to variance-covariance partitioning reveals if trade-offs or suites of correlated traits manifest at the among- or within-individual level, providing insight into underlying mechanisms and evolutionary constraints [26] [25].

Core Concepts and Comparative Framework

The following table defines the key variance components and their biological interpretations.

Table 1: Core components of phenotypic variance and their interpretations.

| Variance Component | Statistical Symbol | Biological Interpretation | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Among-Individual | VA | Consistent, stable differences between individuals over time. | Upper limit for heritability; the primary target of natural selection. |

| Within-Individual | VW | Fluctuation within a single individual across time or contexts. | Measures phenotypic plasticity and environmental sensitivity. |

| Between-Population | VBpop | Average differences between separate populations. | Informs about local adaptation and geographic variation [24]. |

Application in a Signaling Trade-Off

A study on gray treefrogs (Hyla chrysoscelis) provides a classic example. Male advertisement calls feature a trade-off between call duration and call rate. Variance partitioning revealed:

- A negative covariance between call duration and call rate was strongest at the among-individual level [26].

- This indicates that individuals consistently differ in how they resolve this life-history trade-off (e.g., some always produce long, slow calls, while others produce short, rapid calls).

- The among-individual covariance was perpendicular to the direction of sexual selection, suggesting a genetic constraint limiting the response to selection [26].

Application in Hormonal Pleiotropy

A test of the Challenge Hypothesis in canaries (Serinus canaria) used (co)variance partitioning to investigate if testosterone mediates trade-offs between immune function, sexual signaling, and parental care. The analysis found:

- Limited pleiotropic effects of testosterone; most traits showed no significant correlation with testosterone levels at either the among- or within-individual levels [25].

- A within-individual effect where an increase in female testosterone suppressed immune function [25].

- This case demonstrates how partitioning can test central hypotheses by revealing that hormonal regulation may be more trait-specific than previously assumed.

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

The successful application of variance partitioning requires carefully designed experiments to collect repeated measures data.

- Study System: Male gray treefrogs (Hyla chrysoscelis).

- Objective: Partition variance in call duration and call rate to understand the trade-off's evolutionary constraints.

- Experimental Design:

- Animal Collection & Housing: Capture reproductively active males and house them individually.

- Repeated Recording: Record each male's advertisement calls on multiple nights.

- Social Context Manipulation: For each male, record calls during:

- Spontaneous Calling: No external stimulus.

- Playback Trials: Simulate different competition levels using audio playbacks of conspecific calls.

- Trait Quantification: From audio files, extract for each call bout:

- Call Duration (ms)

- Call Rate (calls/sec)

- Call Effort (product of duration and rate)

- Statistical Analysis: Fit a bivariate linear mixed model to the data to partition the phenotypic (co)variance into among-individual and within-individual components.

- Study System: Captive canaries (Serinus canaria).

- Objective: Test the immunocompetence handicap and challenge hypotheses by assessing testosterone's pleiotropic effects.

- Experimental Design:

- Study Population: 47 breeding pairs of canaries in controlled aviaries.

- Repeated Sampling: Over the breeding season, repeatedly measure the following in both males and females:

- Endocrine Measure: Plasma testosterone levels via radioimmunoassay.

- Immune Function: Standard immune assays (e.g., PHA test).

- Sexual Signaling: Male song repertoire size.

- Parental Behavior: Rates of nestling feeding (parental investment).

- Data Structuring: Organize data in a long format where each row is a measurement occasion for an individual.

- Statistical Analysis: Use univariate and multivariate linear mixed models to partition variances and covariances for each trait with testosterone.

Analytical Workflow and Visualization

The statistical analysis of repeated measures data for variance partitioning follows a structured workflow, implemented using the variancePartition package in R or similar tools [27].

The Linear Mixed Model Framework

The core of variance partitioning relies on the linear mixed model [27]. For a given trait, the model is specified as:

[ y = \sum{j} X{j}\beta{j} + \sum{k} Z{k} \alpha{k} + \varepsilon ]

Where:

- ( y ) is the vector of trait measurements across all samples.

- ( X{j}\beta{j} ) are the fixed effects (e.g., age, season, experimental treatment).

- ( Z{k} \alpha{k} ) are the random effects (e.g., individual identity, population).

- ( \varepsilon ) is the residual error.

The variance is then partitioned as:

- Among-Individual Variance: ( \sum{k} \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\alpha_{k}} ) (Variance of random effects)

- Within-Individual Variance: ( \hat{\sigma}^{2}_{\varepsilon} ) (Residual variance)

- Total Variance: ( \hat{\sigma}^{2}{Total} = \sum{j} \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\beta{j}} + \sum{k} \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\alpha{k}} + \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\varepsilon} )

The fraction of variance explained by each component is calculated by dividing its variance by the total variance [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and resources used in experiments featuring variance partitioning.

Table 2: Key research reagents and resources for variance partitioning studies.

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| variancePartition R Package | Fits linear mixed models to high-dimensional data (e.g., gene expression) and quantifies variance explained by multiple variables [27]. | Used to analyze drivers of variation in complex transcriptome studies [27]. |

| Audio Recording & Analysis Software | Records and quantifies animal vocalizations for behavioral trait analysis (e.g., duration, rate). | Used to analyze trade-offs in gray treefrog advertisement calls [26]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits | Precisely measures hormone concentrations (e.g., testosterone) from plasma/serum samples. | Used to measure testosterone levels in canaries to test hormonal pleiotropy [25]. |

| Immune Challenge Assays | Quantifies immune function (e.g., PHA test for cell-mediated immunity). | Used to assess the immunocompetence handicap hypothesis in canaries [25]. |

| Color-Blind Friendly Palettes | Ensures data visualizations are accessible to all readers, including those with color vision deficiency [28]. | Palettes using colors like #0072B2, #D55E00, #009E73 are robust to colorblindness [28]. |

Data Presentation and Comparative Analysis

The following tables summarize quantitative findings from key studies, highlighting the relative importance of different variance components.

Table 3: Summary of variance partitioning results in gray treefrogs (Hyla chrysoscelis) [26].

| Trait | Repeatability (VA / VP) | Among-Individual Variance (V_A) | Within-Individual Variance (V_W) | Key (Co)variance Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call Duration | Significant (within & across contexts) | High | Lower than V_A | Significant negative among-individual covariance with call rate. |

| Call Rate | Significant (within & across contexts) | High | Lower than V_A | Significant negative among-individual covariance with call duration. |

| Call Effort | Significant (within & across contexts) | High | Lower than V_A | - |

Table 4: Summary of variance partitioning results in canaries (Serinus canaria) regarding testosterone correlations [25].

| Trait Correlation with Testosterone | Among-Individual Correlation | Within-Individual Correlation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Function (Female) | Not Significant | Negative | Increase in female testosterone suppresses immune function. |

| Song Repertoire Size (Male) | Positive | Not Significant | Males with higher average testosterone have larger song repertoires. |

| Parental Care (Male/Female) | Not Significant | Not Significant | Testosterone does not mediate parental investment trade-offs. |

Variance partitioning is an indispensable tool for dissecting the architecture of phenotypic variation, directly informing the broader thesis on individual predictability in wildlife. The comparative analysis reveals that:

- The among-individual variance component (V_A) is critical for identifying evolutionary constraints, as demonstrated by the genetically structured trade-off in treefrog calls [26].

- A comprehensive understanding requires partitioning covariances in addition to variances to test hypotheses about hormonal pleiotropy or behavioral syndromes [25].

- The choice of statistical tools and experimental design is paramount, with linear mixed models providing the flexibility for accurate estimation in complex study designs [27].

This approach allows researchers to move beyond simple mean-level analyses to a richer understanding of how consistent differences between individuals and contextual plasticity shape the diversity of life.

A Guide to Studying Among-Individual Variation from Movement Ecology Data

In movement ecology, a significant paradigm shift is underway, moving the focus from population-level patterns to the biological significance of individual behavioral differences. Modern animal tracking and biologging devices record vast amounts of high-resolution data on individual movement behaviors in natural environments [1]. Traditionally, movement ecologists have often treated unexplained variation around population means as statistical "noise" [1]. However, the field of behavioral ecology has demonstrated that this "noise" contains biologically meaningful information about intrinsic individual differences [1].

This guide examines the conceptual framework and analytical approaches for quantifying individual variation in movement ecology, positioning this research within the broader thesis of individual predictability differences in wildlife research. By systematically studying among-individual variation, researchers can address fundamental questions about behavioral specialization, behavioral syndromes, and how consistent individual differences might affect fitness and population dynamics [1] [29].

Theoretical Foundation: Key Concepts and Terminology

The study of individual variation in movement behaviors adopts a specific terminology from behavioral ecology, centered on statistical partitioning of behavioral variation [1].

Table 1: Key Terminology in Among-Individual Variation Research

| Term | Definition | Statistical Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Personality | Among-individual variation in average behavioral expression across time and context [1] | Variance of a random intercept in mixed-effects models; quantified as repeatability (R) |

| Behavioral Type | An individual's average behavioral expression [1] | Individual's value of the random intercept of its reaction norm |

| Behavioral Plasticity | Reversible changes in behavior in response to environmental conditions within the same individual [1] | Non-zero reaction norm slope in a random regression model |

| Behavioral Syndrome | Correlation between an individual's average expression of one behavior with its average expression of other behaviors [1] | Significant correlation at the among-individual level |

| Predictability | Among-individual differences in residual within-individual behavioral variability after controlling for variation in average behavior and plasticity [1] | Differences in residual variance around individual mean |

The framework moves beyond the traditional "two-step approach" that relies on experimental tests, instead advocating for directly quantifying individual differences from movement data through variance partitioning [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying larger, elusive, or endangered wildlife where experimental approaches may be logistically or ethically challenging [1].

Methodological Framework: Variance Partitioning Approach

The core analytical approach for studying among-individual variation involves partitioning behavioral variability into its environmental, among-individual, and within-individual sources using mixed-effects models [1]. This statistical framework allows researchers to quantify multiple aspects of individual variation simultaneously.

Experimental Protocol for Variance Partitioning

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for implementing variance partitioning in movement ecology studies:

Figure 1: Analytical Workflow for Partitioning Behavioral Variation in Movement Data

Essential Movement Metrics for Individual Variation Studies

Movement ecologists can extract various metrics from tracking data to quantify individual differences in movement behavior [30]:

Table 2: Key Movement Metrics for Studying Individual Variation

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Biological Interpretation | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Characteristics | Step length, Turning angle, Speed, Persistence velocity [30] | Motion capacity, Movement strategy | High-frequency GPS data |

| Space Use Patterns | Net squared displacement, Straightness index, Tortuosity [30] | Exploration tendency, Movement efficiency | Continuous tracking data |

| Recursion Behavior | Residence time, Return time, Revisitation rate [30] | Site fidelity, foraging specialization | Long-term tracking |

| Energetics | Overall dynamic body acceleration (ODBA) [30] | Energy expenditure, Activity budget | Accelerometer data |

The statistical analysis involves fitting mixed-effects models with individual identity as a random effect to partition variance [1]. For example, a random regression approach can be used to estimate both individual differences in average behavior (random intercepts) and individual differences in behavioral plasticity (random slopes) [1].

Comparative Analytical Approaches

Researchers have multiple options for analyzing among-individual variation in movement data, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Table 3: Comparison of Analytical Approaches for Individual Variation

| Method | Primary Use Case | Data Requirements | Outputs | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Partitioning | Quantifying proportional variance attributed to among-individual differences [1] | Repeated measures of the same individuals | Repeatability estimates, Variance components | Requires balanced repeated measures |

| Random Regression | Modeling individual differences in behavioral plasticity across environmental gradients [1] | Observations across varying environmental conditions | Individual reaction norms, Slope variation | Complex model specification |

| Behavioral Syndrome Analysis | Identifying correlations among multiple behaviors at the individual level [1] | Multiple behavioral measures per individual | Behavioral correlation matrices | Risk of spurious correlations |

| State-Space Models | Inferring hidden behavioral states from movement paths [30] | High-resolution movement data | Behavioral state sequences, Transition probabilities | Computational complexity |

The choice of analytical method depends on the research question, data structure, and specific aspects of individual variation being investigated. Each method provides complementary insights into different facets of among-individual differences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Implementing individual variation research in movement ecology requires specific methodological tools and approaches:

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Individual Variation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Technology | GPS loggers, Accelerometers, Bio-logging devices [1] [31] | Collect high-resolution movement and behavioral data | Recording position, activity, physiology |

| Visualization Software | DynamoVis [31], moveVis [31] | Visual exploration of movement patterns in relation to internal and external factors | Creating custom animations, Identifying patterns |

| Statistical Environments | R with specialized packages (e.g., nlme, lme4, MCMCglmm) [1] | Implementing mixed models for variance partitioning | Estimating repeatability, Behavioral syndromes |

| Movement Analysis Tools | Movement metrics calculators, State-space models [30] | Deriving movement characteristics and behavioral states | Calculating step lengths, Identifying behavioral states |

Case Study Application: African Elephant Research

A worked example with 35 African elephants illustrates the application of this framework [1]. The research demonstrated that:

- Behavioral Types: Elephants differed in their average movement behaviors, including net displacement and residence times.

- Individual Plasticity: Elephants varied in how they adjusted movement rates over temporal gradients.

- Predictability: Individuals ranged from more to less predictable in their movement patterns.

- Behavioral Syndrome: Two movement behaviors were correlated, with farther-moving individuals having shorter mean residence times [1].

This case study exemplifies how the variance partitioning approach can reveal complex patterns of individual differences in wildlife movement.

Conceptual Framework Linking Individual Variation to Ecological Processes

The study of individual variation in movement behaviors connects to broader ecological processes through multiple pathways:

Figure 2: Ecological Consequences of Individual Variation in Movement

Recent meta-analytic evidence has revealed that individual differences in behavior explain a significant but small portion (5.8%) of the variance in survival [29]. Interestingly, contrary to theoretical predictions, riskier behavioral types were found to live significantly longer in the wild, but not in laboratory environments, suggesting that individuals expressing risky behaviors might be of overall higher quality [29].

Future Directions and Conservation Applications

The study of individual variation in movement ecology presents several promising research directions with important conservation implications:

- Individual Differences in Vulnerability: Variation in movement and predictability can affect an individual's risk to be hunted or poached, opening new avenues for assessing population viability [1].

- Specialization Patterns: Evidence from marine predators shows individuals often specialize in specific foraging strategies, with some populations harboring a mix of foraging specialists and generalists [1].

- Human-Induced Selection: Human activities may inadvertently select for certain behavioral types, potentially altering population-level behavioral composition [1].

Understanding these individual differences provides crucial insights for developing targeted conservation strategies that account for the substantial variation in how individuals within populations interact with their environment and respond to anthropogenic pressures.

The Role of Biologging, Tracking, and Accelerometer Data in Behavioral Research

The field of behavioral ecology has undergone a significant transformation, shifting its focus from population-level averages to the intrinsic individual variation around these means. This paradigm shift recognizes that consistent individual differences in behavior, often termed animal personality, can have profound ecological consequences, affecting predator-prey interactions, population dynamics, and dispersal [1]. Biologging technologies—animal-borne sensors that record data on movement, acceleration, and physiology—have emerged as a primary tool for studying these individual behaviors in natural environments without the need for disruptive direct observation [32] [33].

The integration of accelerometers and other sensors into tracking devices has been particularly revolutionary. These devices generate large, continuous datasets ideal for quantifying individual behavioral types, plasticity, and predictability over meaningful timescales [1]. This review compares the performance of current biologging methodologies, detailing their experimental protocols and their specific application to uncovering individual predictability differences in wildlife research.

Key Concepts: Individual Variation in Behavior

Behavioral ecologists use repeated measures of individual behavior to partition variability into several key components, which can be directly studied from movement and accelerometer data [1].

- Animal Personality (Behavioral Type): Intrinsic among-individual variation in average behavioral expression. An individual's behavioral type is its position on a behavioral spectrum (e.g., consistently more active or less active) [1].

- Behavioral Plasticity: The reversible change in an individual's behavior in response to environmental gradients. Variation in plasticity exists when individuals differ in their responsiveness to the same environmental cue [1].

- Behavioral Predictability: The consistency of an individual's behavior around its own mean. Some individuals are highly consistent (predictable) in their actions, while others show high residual variability [1].

- Behavioral Syndrome: A correlation between an individual's average expression of one behavior and its average expression of other behaviors, indicating a constrained behavioral style [1].

Comparative Analysis of Biologging Technologies

The table below compares the primary sensor modalities used in biologging for behavioral classification, highlighting their strengths and limitations in quantifying individual behavioral variation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biologging Sensor Modalities for Behavioral Classification

| Sensor Modality | Primary Measured Variables | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Exemplary Accuracy & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometry | Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA), body posture, movement intensity waveforms [34]. | High accuracy for distinct, postural behaviors; well-established machine learning pipelines [35] [34]. | Struggles with fine-scale, peripheral behaviors; data can be energy-intensive to collect and transmit [32] [36]. | 94.8% overall accuracy classifying foraging, resting, and lactation in wild boar using 1 Hz ear-tags [34]. |

| Magnetometry (Coupled with a magnet) | Magnetic field strength (MFS) as a proxy for distance between body parts [32]. | Directly measures fine-scale, peripheral appendage movements (e.g., jaw angles, ventilation); applicable to small species [32]. | Requires careful calibration and attachment of an external magnet; sensitive to sensor-magnet orientation [32]. | Successfully quantified shark jaw angle during foraging and scallop valve angles on a circadian rhythm [32]. |

| Multi-Sensor Fusion (Accelerometer + GPS + Gyroscope) | Tri-axial acceleration, position, and rotation [36]. | Richer data context improves classification accuracy; enables detailed biomechanical and energetic studies (e.g., white stork flight) [33] [36]. | Highest energy consumption; requires sophisticated on-board processing or massive data transmission, limiting operational lifespan [36]. | On-board decision trees achieved >80% accuracy in behavior detection, enabling selective transmission to save energy [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Biologging Methodologies

Protocol 1: Magnetometry for Appendage Movement Tracking

This novel method uses a magnetometer as a proximity sensor for a magnet affixed to a moving appendage, enabling direct measurement of behaviors like foraging, ventilation, and propulsion [32].

- Sensor and Magnet Selection:

- Size & Mass: The combined mass of the tag and magnet should adhere to the 3% body mass rule or more recent athleticism-based metrics [32].

- Magnet Strength: The magnet's "magnetic influence distance" must be greater than the maximum expected movement range (e.g., greater than a bivalve's maximum valve gape) [32].

- Placement: The magnet is affixed to the moving appendage (e.g., lower valve of a scallop, jaw of a shark), while the sensor tag is placed on the main body [32].

- Orientation: For cylindrical magnets, the flat pole surfaces should be oriented normal to the magnetometer to maximize the measurable range of magnetic field strength [32].

- Calibration Procedure:

- Post-deployment, the appendage is manipulated to known distances or angles.

- The magnetic field strength (MFS) is recorded at each discrete position.

- A continuous model is fit to the data to convert MFS to distance:

d = [x1 / (M(o) - x3)]^0.5 - x2, wheredis distance andM(o)is the root-mean-square of tri-axial MFS [32]. - Distance can be converted to joint angle using the equation:

a = 2 • arcsin(0.5d / L), whereLis the distance from the joint to the tag or magnet [32].

- Data Analysis: The calibrated distance/angle time series is analyzed to identify and characterize specific behavioral events (e.g., chewing, valve opening, fin beats) and their timing [32].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the magnetometry appendage tracking protocol:

Protocol 2: Machine Learning for Behavioral Classification from Accelerometers

Accelerometer data is commonly used with machine learning (ML) models to classify behavior. Key considerations include data resolution and model selection [35] [34].

- Data Collection & Preprocessing:

- Sampling Rate: Ranges from 1 Hz (low-frequency, energy-efficient) [34] to >10 Hz (high-frequency, captures detailed waveforms) [35].

- Observation & Labeling: Simultaneous visual observations of the tagged animal's behavior are conducted to create a labeled dataset for model training [35].

- Feature Engineering: For low-resolution data, static features (e.g., mean, variance, ODBA) from raw, gravitational, and movement-related acceleration are calculated over time windows (e.g., 5-10 seconds) [35] [34].

- Model Training & Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Common algorithms include Random Forest (RF) [34], Discriminant Analysis [35], and Decision Trees [36].

- Training Approach: A supervised learning approach is used where acceleration features are input variables and observed behaviors are output variables [35].

- Validation & Metrics: Models are validated on hold-out data. Balanced accuracy is crucial for imbalanced datasets [35] [34].

- Application: The trained model is used to predict behavior from new, unlabeled accelerometer data [35] [36].

The workflow for developing and applying a behavioral classification model is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Technologies for Biologging Behavioral Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Specifications | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| WildFi Tag | A state-of-the-art, lightweight bio-logger for multi-sensor data collection and transmission [36]. | 9-axis IMU (accelerometer, gyro, magnetometer), GPS, WiFi; Weight: ~1.28g [36]. | Used in energy-efficient ML studies; enables sensor fusion for improved classification [36]. |

| VECTRONIC GPS Collars | GPS collars with integrated accelerometers for large mammals like red deer [35]. | Measures x, y (and sometimes z) axis acceleration, averaged over 5-min intervals [35]. | Used in studies comparing ML algorithms for classifying behavior in wild cervids [35]. |

| Neodymium Magnet | Creates a measurable magnetic field for tracking appendage movement via magnetometry [32]. | Size/material chosen based on required "magnetic influence distance"; often cylindrical [32]. | Critical for measuring scallop valve angles, shark jaw movement, and fish operculum beats [32]. |

| Random Forest (RF) Algorithm | A machine learning method for classifying behavior from acceleration or other sensor data [34]. | An ensemble of decision trees; robust to overfitting [34]. | Achieved 94.8% accuracy classifying behavior in wild boar using low-frequency (1 Hz) data [34]. |

| Decision Trees | A simpler ML algorithm suitable for on-board processing on bio-loggers to enable selective data transmission [36]. | Flowchart-like model; can be optimized for low computational cost [36]. | Enables energy savings by transmitting only data related to specific behaviors of interest [36]. |

Biologging technologies have moved beyond simply tracking an animal's location to providing deep, mechanistic insights into the individual differences that drive behavioral diversity. The comparative analysis shows that magnetometry offers a unique solution for measuring fine-scale appendage movements, while accelerometry paired with machine learning remains a powerful and versatile tool for classifying broader behavioral states. The choice of sensor and analytical protocol depends heavily on the specific research question, target species, and the aspect of individual variation under investigation.

Emerging trends point towards multi-sensor fusion and on-board intelligence as the future of the field. By processing data directly on the tag, researchers can make biologgers more energy-efficient, allowing for longer-term studies that are essential for capturing the full scope of individual behavioral types, plasticity, and predictability in wildlife [33] [36]. This, in turn, will provide vital insights for conservation, enabling a more nuanced understanding of population viability and species resilience in a rapidly changing world [33].