Beyond Tracking: How Accelerometers are Revolutionizing Wildlife Biologging and Revealing the Secret Lives of Animals

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of accelerometers in wildlife biologging.

Beyond Tracking: How Accelerometers are Revolutionizing Wildlife Biologging and Revealing the Secret Lives of Animals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of accelerometers in wildlife biologging. It explores the foundational principles of how these sensors capture animal movement and behavior, details the methodological approaches for classifying behaviors and estimating energy expenditure, and addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization techniques for data accuracy. Furthermore, it examines validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different sensor configurations. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide best practices and highlights future directions for integrating high-resolution accelerometer data into ecological and conservation research.

The Unobservable Made Visible: Core Principles and Exploratory Applications of Bio-Logging

Bio-logging involves attaching miniature electronic devices to animals to record data about their physiology, movement, and environment [1]. These devices have revolutionized our understanding of wild animal ecology by providing insights into the secret lives of animals that would otherwise be challenging to obtain via direct observation [1]. Among the most powerful sensors in the bio-logging toolbox are accelerometers, which measure acceleration in up to three dimensional axes at high frequencies, typically in units of gravitational force (g) [2].

The acceleration measured by these devices consists of two components: static acceleration and dynamic acceleration [2]. Static acceleration reflects the angular incidence of the device relative to the gravitational field and provides information on posture and orientation [2]. Dynamic acceleration represents the component attributable to movement of the animal itself [2]. The separation and analysis of these components enable researchers to identify specific behaviors, estimate energy expenditure, and understand how animals interact with their environments [3].

The development of acoustic accelerometer transmitters has further expanded applications by allowing data summaries to be transmitted to receivers without requiring tag recovery [2]. This is particularly valuable for studying cryptic species that are difficult to recapture [2]. As technology continues to advance, bio-logging devices have become increasingly miniaturized, enabling deployment on a wider range of species, from large marine mammals to small birds and even insects [1].

Technical Specifications and Sensor Fundamentals

Key Technical Parameters

Accelerometer specifications must be carefully selected to optimize data collection for specific research questions. The sampling rate (number of measurements per second) and sampling window (duration of measurement before transmission) significantly impact the types of behaviors that can be resolved [2].

Table 1: Standard Accelerometer Transmitter Specifications in Ecological Studies

| Parameter | Common Settings | Biological Significance | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Rate | 5-12.5 Hz (most common: 5 Hz or 10 Hz) [2] | Must be at least twice the maximum tail beat frequency for fish [2] | Higher rates (≥30 Hz) needed for detailed behavioral classification [2] |

| Sampling Window | 0.25-180 seconds (mean: 34s, median: 25s) [2] | Shorter windows provide behavioral snapshots; longer windows give synoptic activity views [2] | Heterogeneous activity states may be averaged in longer windows [2] |

| Operation Mode | 2-axis (tailbeat) or 3-axis (activity) [2] | 2-axis measures undulations (e.g., tail beats); 3-axis provides general activity estimation [2] | Axis-free algorithms being developed to reduce transmission burden [2] |

| Additional Sensors | Pressure (depth), temperature [2] | Provides environmental context for behavioral data [2] | Temperature sensors surprisingly rare despite metabolic implications [2] |

Data Processing and Metrics

Raw acceleration data undergoes processing to extract biologically meaningful metrics. The most common derived metric is Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA), which serves as a validated proxy for movement-based energy expenditure across diverse vertebrate and invertebrate species [3]. DBA is calculated by first removing the static gravitational component, then calculating the vectorial sum of the dynamic acceleration components [3]. The vectorial norm (or magnitude) of dynamic acceleration is calculated using the formula:

‖a‖ = √(x² + y² + z²)

where x, y, and z are the dynamic acceleration values along the three axes [3]. This metric correlates well with energy expenditure measured through oxygen consumption, making it particularly valuable for ecological studies [3].

Methodological Considerations and Protocols

Sensor Calibration Procedures

Proper accelerometer calibration is essential for generating comparable, accurate data. Laboratory tests have demonstrated that uncalibrated tags can produce DBA differences of up to 5% compared to calibrated tags [3]. The 6-Orientation (6-O) method provides a simple field calibration technique that should be executed prior to deployments and archived with resulting data [3].

Table 2: Accelerometer Calibration Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-deployment Setup | Place tag motionless in six defined orientations (each for ~10 seconds) with one axis perpendicular to gravity [3] | Allows calculation of correction factors for each axis [3] | Vector sum should be ≈1.0g for perfect calibration [3] |

| 2. Data Collection | Record raw acceleration values in each orientation [3] | Capture maxima and minima for each acceleration axis [3] | Note any deviations from expected ±1g values for each axis [3] |

| 3. Correction Application | Apply two-level correction: equalize absolute maxima per axis, then apply gain to convert to exactly 1.0g [3] | Eliminate measurement error inherent in sensor fabrication [3] | Verify all six maxima read 1.0g after correction [3] |

| 4. Documentation | Archive calibration parameters with resulting data [3] | Enable future data comparison and meta-analyses [3] | Record tag type, calibration date, and methodology [3] |

Tag Attachment and Placement

Tag placement critically affects signal amplitude and quality. Research has demonstrated that device position can create greater variation in DBA than calibration errors, with upper and lower back-mounted tags varying by 9% in pigeons, and tail- and back-mounted tags varying by 13% in kittiwakes [3]. The following protocol ensures standardized attachment:

Position Selection: Choose tag placement based on species morphology and research questions. For birds, common positions include lower back, tail, or belly [3]. For terrestrial mammals, collars provide relatively standardized attachment [3].

Orientation: Place transmitters lengthwise in an anterior-posterior position to ensure acceleration along the Y-axis (forward/backward) is represented appropriately [2].

Secure Attachment: Use attachment methods that minimize independent tag movement. Internally implanted tags should be secured to the body wall with sutures where appropriate [2]. External attachments should use epoxy, dart tags, clamps, or saddles sufficient to prevent motion not caused by the animal [2].

Documentation: Record precise attachment location and method to enable comparison across studies and assessment of potential biases [3].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Behavioral Classification

Accelerometer data can be used to identify specific behaviors through machine learning approaches. Successful behavioral identification has been demonstrated across diverse taxa:

- Bengal slow loris: Random forest models achieved 80.7 ± 9.9% accuracy in predicting behaviors, with resting predicted with 99.8% accuracy [1].

- Banded mongoose: Accelerometers reliably identified scent marking, running, and vigilance behaviors [4].

- Sea turtles: Convolutional neural networks identified the egg-laying process, enabling automated monitoring of nesting populations [1].

The general workflow for behavioral classification involves collecting labeled acceleration data (often through video validation), feature extraction from the acceleration signals, training of classification models, and application to unlabeled field data [1].

Time-Series Analysis Considerations

Biologging data present unique analytical challenges due to their time-series nature, often exhibiting strong autocorrelation where successive values depend on prior measurements [5]. Analyses must account for this temporal autocorrelation to avoid inflated Type I error rates [5].

Appropriate analytical approaches include:

- Autoregressive (AR) models: Account for correlation between consecutive residuals in the time series [5].

- Autoregressive moving average (ARMA) models: Combine both autoregressive and moving average components for greater flexibility [5].

- Generalized least squares (GLS) models: Control Type I error rates at appropriate levels when examining temporal trends [5].

Applications in Ecological Research

Behavioral Ecology and Conservation

Accelerometers have enabled significant advances in understanding animal behavior and ecology:

- Migration and Movement Ecology: Studies have tracked the long-distance migrations of species like common cranes across diverse habitats, providing insights into their seasonal movement strategies and identifying critical bottlenecks [6].

- Foraging Ecology: Research on species like red-tailed tropicbirds has used DBA to understand how animals adjust foraging effort in response to environmental conditions [3].

- Response to Environmental Change: Acceleration metrics help quantify how animals respond to changes in food availability, climate, and anthropogenic threats [3].

Energy Expenditure and Physiology

The relationship between DBA and energy expenditure has been validated across numerous species, making accelerometry a powerful tool for physiological ecology:

- Energy Landscapes: By combining acceleration data with spatial information, researchers can map how energy costs vary across landscapes and seascapes [2].

- Conservation Planning: Understanding movement-based energy expenditure helps identify critical habitats and assess potential impacts of human disturbances [2].

- Exercise Physiology: Accelerometers allow assessment of exercise physiology in wild animals, including responses to stressors and environmental extremes [2].

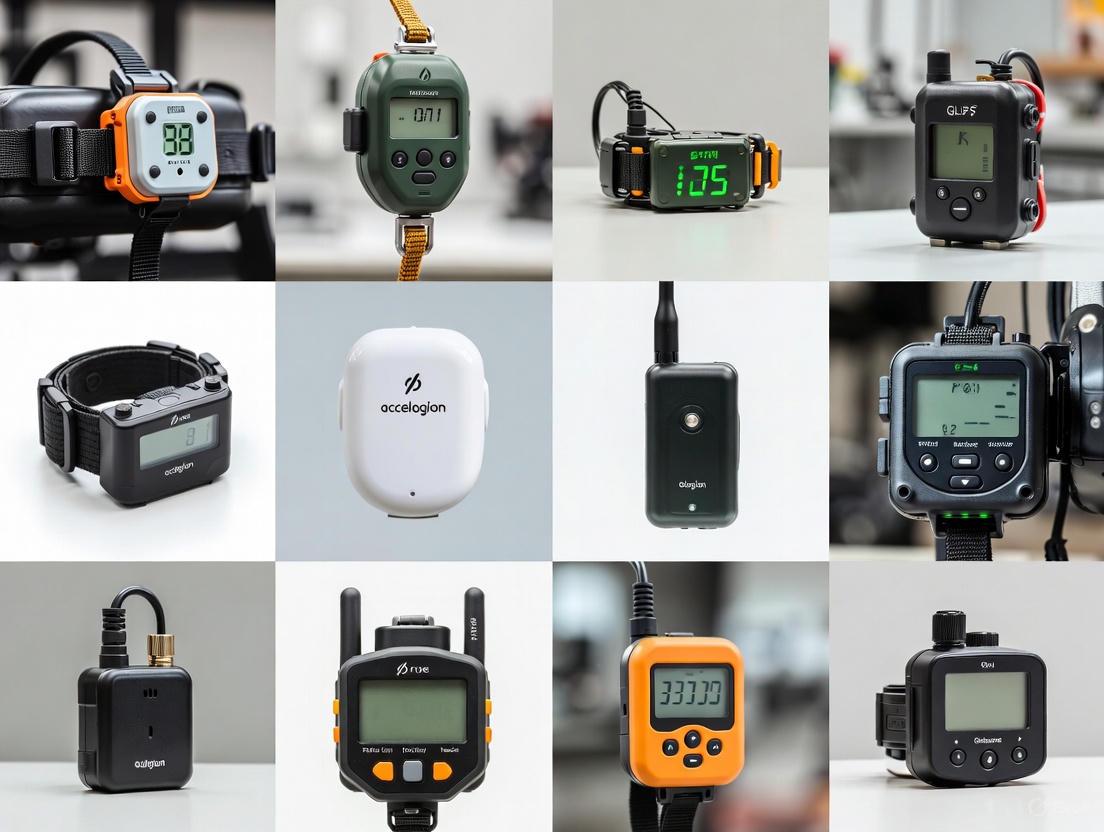

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Biologging Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer Tags | Acoustic transmitters (Vemco/Innovasea), Daily Diary tags (Wildbyte Technologies) [2] [3] | Measure 2- or 3-axis acceleration; some transmit data, others require recovery [2] | Select based on sampling rate needs, battery life, and attachment method [2] |

| Calibration Equipment | Level surface, orientation jig [3] | Execute 6-O calibration method to ensure sensor accuracy [3] | Must be performed before each deployment; data archived with results [3] |

| Attachment Materials | Sutures (internal), epoxy, dart tags, clamps, harnesses [2] | Secure tags to animals with minimal independent movement [2] | Method affects signal quality and potential for tissue damage [2] |

| Validation Tools | Video recording systems [1] | Ground-truth acceleration data for behavioral classification [1] | Essential for developing and training machine learning models [1] |

| Additional Sensors | Pressure sensors, temperature sensors [2] | Provide environmental context for behavioral data [2] | Temperature surprisingly rare despite metabolic implications [2] |

| CX-6258 | CX-6258, MF:C26H24ClN3O3, MW:461.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| UNC2881 | UNC2881, CAS:1493764-08-1, MF:C25H33N7O2, MW:463.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of bio-logging continues to evolve with technological advancements. Future directions include:

- Sensor Miniaturization: Enabling studies on smaller species and longer deployment durations [1].

- Data Transmission Advances: Improving the efficiency of data transmission from acoustic accelerometer transmitters to increase information yield [2].

- Method Standardization: Developing community standards for calibration, attachment, and data processing to enable robust cross-study comparisons [3].

- Multi-sensor Integration: Combining accelerometers with complementary sensors (e.g., GPS, heart rate monitors, environmental sensors) to provide more comprehensive ecological insights [2].

Accelerometer-based bio-logging has fundamentally transformed our ability to study animal behavior, physiology, and ecology in natural settings. By following standardized protocols for sensor calibration, tag attachment, and data analysis, researchers can continue to expand our understanding of the secret lives of animals while ensuring data comparability across studies and species. The revolution in observing animal behavior through bio-logging promises continued insights as technology advances and methodologies mature.

Tri-axial accelerometers are fundamental tools in wildlife biologging that measure proper acceleration, capturing data in three perpendicular dimensions to provide a comprehensive vector of movement. These sensors operate on the principle of measuring inertial forces caused by acceleration, allowing researchers to quantify fine-scale behaviors and movements of free-ranging animals. The core mechanism involves detecting capacitance changes in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) caused by the displacement of a proof mass under acceleration forces. This technological foundation enables the decomposition of an animal's movement into three spatial components: the surge (x-axis), sway (y-axis), and heave (z-axis), corresponding to anterior-posterior, lateral, and dorso-ventral movements respectively [7].

The application of these devices in wildlife studies has revolutionized our understanding of animal behavior, movement ecology, and energy expenditure. By providing continuous, high-resolution data on animal posture, fine-scale movements, and body acceleration, tri-axial accelerometers facilitate the remote monitoring of species in their natural environments without the limitations of direct observation [7] [8]. This technical capacity has proven particularly valuable for studying cryptic species, animals in inaccessible habitats, and behaviors that occur too rapidly for human observers to reliably capture [7] [9].

Fundamental Operating Principles

Physical Sensing Mechanism

At the physical level, tri-axial accelerometers detect acceleration through micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) that measure the displacement of a proof mass suspended by springs. When acceleration occurs, the proof mass moves from its neutral position due to inertia, and this displacement is measured electronically. Most modern biologging accelerometers use capacitive sensing, where the displacement changes the capacitance between fixed plates and plates attached to the proof mass. These capacitance changes are then converted to digital output values representing acceleration forces [3].

The sensors measure two distinct types of acceleration: static acceleration caused by gravity, which indicates orientation and posture, and dynamic acceleration resulting from animal movement [8]. The separation and analysis of these components enable researchers to distinguish between different behaviors and postural states. The vector sum of the three acceleration axes should theoretically equal 1g when the device is stationary, a fundamental principle used for device calibration and validation [3].

Data Components and Interpretation

The raw output from tri-axial accelerometers consists of three continuous data streams, one for each orthogonal axis. The static acceleration component remains relatively constant during postural positions and provides information about the animal's orientation relative to gravity. The dynamic acceleration component fluctuates rapidly with movement and contains information about specific behaviors and motion characteristics [8].

For wildlife applications, researchers often calculate derived metrics from the raw acceleration data:

- Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA): The sum of the absolute values of dynamic acceleration from all three axes [8]

- Vector of Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA): The square root of the sum of squared dynamic accelerations across axes [3]

- Static acceleration vectors: Used to determine body posture and orientation [8]

These metrics serve as proxies for energy expenditure and enable the classification of specific behaviors based on their unique acceleration signatures [3] [8].

Technical Specifications and Measurement Parameters

Table 1: Key Technical Parameters of Tri-axial Accelerometers in Wildlife Research

| Parameter | Specification Range | Biological Significance | Example Values from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Frequency | 2-100 Hz | Must exceed Nyquist frequency of target behaviors; higher for rapid movements [9] | 2 Hz (sea turtles) to 100 Hz (bird flight) [9] [10] |

| Dynamic Range | ±2g to ±8g | Must encompass maximum acceleration of study species | ±2g (green turtles), ±4g (loggerhead turtles) [10] |

| Resolution | 8-16 bit | Determines sensitivity to detect subtle movements | 8-bit [9] [10] |

| Measurement Error | Variable; requires calibration | Impacts accuracy of energy expenditure estimates [3] | Up to 5% error in DBA without calibration [3] |

Table 2: Accelerometer Outputs and Their Behavioral Correlates in Wildlife Studies

| Output Metric | Calculation Method | Behavioral/Ecological Interpretation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODBA | Sum of dynamic acceleration magnitudes across all three axes [8] | Proxy for movement-based energy expenditure [8] | Comparing energy costs across environments [3] |

| VeDBA | Vector magnitude of dynamic acceleration: √(xdyn² + ydyn² + z_dyn²) [3] | Improved proxy for energy expenditure, less affected by orientation [3] | Field energy estimation in seabirds [3] |

| Pitch | arctan(x / √(y² + z²)) | Head position/body orientation during feeding or resting | Determining feeding bouts in black cockatoos [7] |

| Roll | arctan(y / √(x² + z²)) | Lateral body positioning during maneuvering | Flight characterization in vultures [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Wildlife Biologging

Device Calibration Procedures

Field-Based Calibration Method (6-O Method) Prior to deployment, accelerometers must be calibrated to ensure measurement accuracy. The 6-O method involves placing the device motionless in six defined orientations where each axis sequentially points upward and downward [3]:

For each orientation, record approximately 10 seconds of data while the device is stationary. Calculate the vector sum ‖a‖ = √(x² + y² + z²) for each stationary period, which should equal 1g for perfectly calibrated devices. Compute correction factors for each axis to ensure both positive and negative measurements are symmetrical and normalized to 1g [3]. This calibration corrects for sensor imperfections and manufacturing variances that can introduce error in acceleration measurements.

Device Attachment and Deployment

The attachment method and position critically influence data quality and animal welfare. The general protocol includes:

Device Selection: Choose devices weighing less than 3-5% of the animal's body mass to minimize impact on behavior and energy expenditure [7].

Position Determination: Select attachment position based on species morphology and target behaviors. For seabirds, common positions include the back, tail, or belly; for marine turtles, placement varies by scute position [10] [3].

Secure Attachment: Use species-appropriate attachment methods. For birds, this may include leg-loop harnesses or attachment to feathers; for marine species, use waterproof adhesives compatible with the animal's skin or shell [9] [10].

Configuration Settings: Program sampling frequency based on the Nyquist-Shannon theorem—at least twice the frequency of the fastest behavior of interest [9]. For short-burst behaviors, higher sampling frequencies (up to 100 Hz) may be necessary [9].

Behavioral Classification Workflow

The process of classifying behaviors from accelerometer data follows a structured workflow from data collection to validation:

Step 1: Ground Truthing Collect synchronized accelerometer data and video recordings of animal behavior in controlled settings or during focal observations [7] [10]. For captive black cockatoos, this involved mounting cameras in flight aviaries to record behaviors simultaneously with accelerometer data [7]. For sea turtles, researchers used GoPro cameras mounted above tanks or on telescopic poles, along with animal-borne video cameras [10].

Step 2: Data Segmentation and Feature Extraction Segment the continuous accelerometer data into windows of consistent duration (e.g., 1-2 seconds) [10]. For each window, calculate summary metrics including:

- Mean acceleration for each axis (indicating posture)

- Variance of each axis (indicating movement intensity)

- Covariance between axes (indicating movement patterns)

- VeDBA or ODBA (indicating energy expenditure) [10] [8]

Step 3: Model Training Use machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, or Artificial Neural Networks to build classifiers that associate acceleration features with specific behaviors [10] [8]. Implement cross-validation techniques that account for individual variation, such as leave-one-individual-out validation [10].

Step 4: Application and Validation Apply the trained classifier to unlabeled accelerometer data from wild individuals. Validate classifier performance against direct observations or video recordings where possible [7]. For black cockatoos, this process achieved 86% accuracy in classifying resting, flying, and foraging behaviors [7].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Wildlife Accelerometer Studies

| Material/Equipment | Specification Guidelines | Primary Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tri-axial accelerometer | MEMS-based, appropriate weight limit, programmable sampling frequency | Measures acceleration in three dimensions | Select dynamic range suitable for target species; consider battery life vs. sampling frequency trade-offs [9] |

| Data storage/transmission | On-board memory or remote transmission capability | Stores and retrieves acceleration data | Memory capacity limits deployment duration; high-frequency sampling fills memory faster [9] |

| Attachment materials | Species-appropriate: harnesses, adhesives, waterproof tapes | Secures device to animal without injury | VELCRO with superglue and waterproof tape used for sea turtles [10]; leg-loop harnesses for birds [9] |

| Synchronization tools | GPS time sources, video recording with time display | Synchronizes accelerometer data with behavioral observations | Use UTC time sources like time.is or GPS apps for accurate synchronization [10] |

| Calibration equipment | Level surface, multiple orientation jig | Ensures measurement accuracy before deployment | 6-O method provides field-expedient calibration [3] |

Optimization Considerations for Wildlife Research

Sampling Frequency Requirements

The appropriate sampling frequency depends on the specific behaviors of interest and their temporal characteristics. The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem dictates that the sampling frequency must be at least twice the frequency of the fastest behavior essential to characterize [9]. However, practical applications often require oversampling:

- For long-endurance, rhythmic behaviors like flight in birds, sampling at 12.5 Hz may be sufficient [9]

- For short-burst, abrupt behaviors like swallowing in pied flycatchers (mean frequency 28 Hz), sampling at 100 Hz was necessary [9]

- For sea turtle behaviors, no significant improvement in classification accuracy was observed beyond 2 Hz, enabling longer deployments with lower power consumption [10]

Device Placement Effects

Accelerometer position on the animal's body significantly affects signal characteristics and classification accuracy:

- In seabirds, tail-mounted tags showed 13% variation in VeDBA compared to back-mounted tags [3]

- In sea turtles, placement on the third scute provided significantly higher classification accuracy than placement on the first scute [10]

- Computational Fluid Dynamics modeling revealed that device position affects hydrodynamic drag, with first scute attachment increasing drag coefficient significantly [10]

These findings highlight the importance of standardizing attachment positions within studies and carefully considering the trade-offs between signal quality and animal welfare when determining tag placement.

The core mechanism of tri-axial accelerometers—measuring inertial forces through MEMS technology—provides wildlife researchers with a powerful tool for quantifying animal behavior, energy expenditure, and movement ecology. The successful application of this technology requires careful attention to calibration protocols, sampling parameters, device placement, and validation procedures. By following the detailed application notes and protocols outlined in this document, researchers can enhance the quality and reliability of accelerometer data in wildlife biologging studies, leading to more robust ecological inferences and effective conservation strategies.

In the realm of wildlife biologging, tri-axial accelerometers have emerged as pivotal tools for transforming raw movement data into quantifiable metrics of animal behavior, energy expenditure, and body orientation [1]. These sensors measure acceleration along three orthogonal axes, typically categorized into static and dynamic components [11]. The static component, primarily reflecting gravitational acceleration, enables the calculation of body posture and orientation metrics such as pitch and roll [1]. Conversely, the dynamic component represents movement generated by the animal itself, forming the basis for proxies of energy expenditure like Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA) and Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA) [11] [12]. The derivation and application of these metrics represent a cornerstone of modern movement ecology, facilitating non-invasive insight into the secret lives of animals across diverse taxa, from flying birds and swimming turtles to terrestrial mammals [1] [10]. Their calculation forms a standardized pipeline for converting high-frequency, raw sensor data into ecologically meaningful information, enabling researchers to test hypotheses about animal energetics, behavioral ecology, and conservation physiology.

Core Metric Definitions and Calculations

The fundamental accelerometer metrics used in ecology are derived through specific computational procedures applied to raw tri-axial data. The table below summarizes the core formulae and ecological applications of these key derivatives.

Table 1: Core Accelerometer Metrics in Wildlife Biologging

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Description | Primary Ecological Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Acceleration | Running mean (e.g., over 2 s) of raw acceleration for each axis [11]. | The low-frequency component of acceleration, dominated by the gravitational field. | Used to derive body posture and orientation (pitch and roll) [1]. |

| Dynamic Acceleration | Raw acceleration - Static acceleration [11]. | The high-frequency component of acceleration, generated by animal movement. | The fundamental input for calculating ODBA and VeDBA [11]. |

| ODBA | (\sum |D{x}| + |D{y}| + |D{z}|)Where (D{x}, D{y}, D{z}) are dynamic acceleration for x, y, z axes [11]. | The sum of the absolute values of dynamic acceleration from the three orthogonal axes. | A common proxy for energy expenditure or metabolic rate [11] [12]. |

| VeDBA | (\sqrt{D{x}^2 + D{y}^2 + D_{z}^2}) [11] [12] | The vector norm (magnitude) of the dynamic acceleration vector. | An alternative proxy for energy expenditure; may be less sensitive to device orientation [11] [12]. |

| Pitch | (\arcsin\left(\frac{S{x}}{g}\right))Where (S{x}) is static acceleration on the surge (x) axis and (g) is gravity [1]. | The vertical orientation of the animal's body, describing head-up/head-down angle. | Classifying behaviors (e.g., diving vs. surfacing); understanding locomotion kinematics [1]. |

| Roll | (\arcsin\left(\frac{S{y}}{g}\right))Where (S{y}) is static acceleration on the sway (y) axis [1]. | The lateral orientation of the animal's body, describing side-to-side tilt. | Assessing lateral movements, turning, and asymmetric body positions [1]. |

ODBA vs. VeDBA: A Comparative Analysis

The choice between ODBA and VeDBA as a proxy for energy expenditure has been a subject of empirical investigation. While both are strongly correlated with the rate of oxygen consumption (( \dot{V}O2 )), studies on humans and other animal species have shown that ODBA can account for slightly but significantly more of the variation in ( \dot{V}O2 ) than VeDBA [11] [12]. This finding suggests that the sum of accelerations along independent axes may effectively capture the energy cost of simultaneous muscle contractions used for limb stabilization and movement [11]. However, VeDBA is theoretically less sensitive to changes in device orientation. Research indicates that in scenarios where consistent logger orientation cannot be guaranteed, VeDBA is the recommended proxy due to its vectorial properties [11] [12].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation and Application

Validating accelerometer metrics and applying them to novel species requires rigorous experimental protocols. The following section details established methodologies for ground-truthing behaviors and optimizing device settings.

Protocol: Ground-Truthing Behaviors for Classification Models

Objective: To develop a supervised machine learning model for classifying animal behavior from accelerometer data. Background: Supervised classification relies on direct observations to train a model, enabling automated behavioral inference from accelerometer readouts [10] [13].

- Device Attachment: Securely attach tri-axial accelerometers to the study animals. The placement should be standardized (e.g., on the back near the center of gravity) to ensure consistent data [10]. For marine turtles, for instance, attachment on the third vertebral scute has been shown to provide higher classification accuracy and lower hydrodynamic drag compared to the first scute [10].

- Data Collection: Configure accelerometers to record at a sufficiently high frequency (e.g., 25-100 Hz) to capture the nuances of target behaviors [9]. Simultaneously, record the animals' behavior using video cameras (e.g., GoPro) synchronized to the accelerometer's internal clock [9] [10].

- Behavioral Annotation: Annotate the synchronized video footage using software like BORIS ("Behavioral Observation Research Interactive Software") to create a detailed ethogram [10]. Omit the first and last second of each behavioral bout to account for synchronization errors [10].

- Data Segmentation and Feature Calculation: Segment the synchronized accelerometer data into windows of fixed length (e.g., 1-second or 2-second windows). For each window and axis, calculate a suite of summary metrics (features) such as mean, standard deviation, and correlation between axes [10].

- Model Training and Validation: Use a machine learning algorithm, such as a Random Forest (RF), to train a classification model [10]. Implement a leave-one-individual-out cross-validation strategy to avoid overfitting and ensure the model generalizes across individuals [10].

Protocol: Optimizing Sampling Frequency and Window Length

Objective: To determine the minimal sampling frequency and analysis window length required to accurately capture behaviors of interest, thereby optimizing battery life and device memory. Background: Sampling at unnecessarily high frequencies drains battery and fills memory rapidly, whereas sampling too low causes loss of critical information [9].

- Pilot Data Collection: Initially collect high-frequency accelerometer data (e.g., 100 Hz) alongside detailed behavioral observations [9].

- Data Down-sampling: Systematically down-sample the original high-frequency dataset to lower frequencies (e.g., 50, 25, 12.5, 2 Hz) [9] [10].

- Performance Evaluation: For each down-sampled frequency, perform behavioral classification or calculate energy expenditure proxies (ODBA/VeDBA). Compare the results against the "gold standard" from the high-frequency data or direct observations.

- Determine Critical Frequency: Identify the minimum frequency at which performance is not significantly degraded. Adhere to the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, which states the sampling frequency should be at least twice that of the fastest movement of interest [9]. For short-burst behaviors (e.g., swallowing in birds), frequencies higher than 100 Hz may be necessary, while for sustained behaviors like flight, 12.5 Hz may be sufficient [9].

- Optimize Window Length: Evaluate the effect of the analysis window length (e.g., 1s vs. 2s) on classification accuracy. Longer windows can provide more stable estimates for rhythmic behaviors, while shorter windows may be needed for brief events [10]. For sea turtles, a 2-second window significantly improved accuracy over a 1-second window [10].

Workflow Visualization: From Data Collection to Ecological Insight

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for processing accelerometer data, from collection to the derivation of ecological insights.

Figure 1: Data processing and analysis workflow for deriving ecological insight from raw accelerometer data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful accelerometer studies rely on a suite of specialized hardware, software, and methodological considerations. The table below catalogs the essential components of the modern biologging toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biologging Studies

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Tri-axial Accelerometer | Measures acceleration in surge, heave, and sway axes. Key specs: sampling frequency (Hz), dynamic range (± g), bit resolution, weight [9] [10]. |

| Hardware | Attachment Harness/Adhesive | Secures device to animal. Leg-loop harness for birds [9]; waterproof adhesive (e.g., super glue) and tape for marine turtles [10]. |

| Hardware | Synchronized Video System | For ground-truthing behaviors. High-speed cameras (e.g., GoPro) synchronized to UTC time [9] [10]. |

| Software | Behavioral Annotation Software | Software like BORIS is used to label observed behaviors from video, creating the dataset for model training [10]. |

| Software | Statistical Computing Platform | R or Python with specialized packages (e.g., caret, ranger in R) for data analysis, feature calculation, and machine learning [10]. |

| Methodology | Ethogram | A predefined catalog of animal behaviors used to standardize behavioral observations and annotations [10]. |

| Methodology | Machine Learning Classifier | Random Forest models are commonly used for their high accuracy in classifying behaviors from accelerometer feature data [10]. |

| Methodology | Cross-Validation Strategy | Leave-one-individual-out cross-validation is critical for generating robust, generalizable models that are not biased by individual idiosyncrasies [10]. |

| MPI-0479605 | MPI-0479605, MF:C22H29N7O, MW:407.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| STF-083010 | STF-083010, MF:C15H11NO3S2, MW:317.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The derivation of key metrics such as ODBA, VeDBA, pitch, and roll from raw accelerometer data represents a standardized and powerful methodology in wildlife research. These metrics serve as fundamental bridges between the complex physical movements of an animal and quantifiable aspects of its ecology, including energy expenditure, behavioral states, and postural dynamics. The rigorous experimental protocols for ground-truthing and device optimization ensure that the data collected are both ecologically meaningful and resource-efficient. As biologging technology continues to advance, the integration of on-board processing and continuous monitoring [13] will further enhance our ability to uncover the drivers of animal behavior, survival, and fitness in a rapidly changing world.

Within the field of wildlife biologging, accelerometers have revolutionized our ability to study the secret lives of animals by providing a window into their behaviors, physiology, and energy demands remotely and continuously [1]. These devices measure proper acceleration, allowing researchers to decipher a wide range of biological phenomena, from fine-scale behaviors and movement ecology to energy expenditure and significant life-history events [1] [14]. The data obtained are instrumental in addressing fundamental ecological questions and understanding how animals respond to environmental changes, such as shifts in climate and land use [14]. This application note details protocols and methodologies for using accelerometers to assess animal activity, energy expenditure, and reproductive events, framed within the context of a broader thesis on wildlife biologging.

Application Note & Experimental Protocols

Quantifying Activity and Behavioural Budgets

Objective: To classify specific behaviours and quantify activity budgets of free-moving animals using tri-axial accelerometers.

Background: Accelerometers record signatures of distinct body movements, which can be matched to specific behaviours [1]. Supervised machine learning is the primary method for automating behaviour classification from acceleration data [15].

Protocol 1: Data Collection for Behaviour Classification

- Tag Selection and Calibration:

- Select a biologger with a tri-axial accelerometer. The device's weight should typically be less than 5% of the animal's body mass.

- Calibration is critical. Prior to deployment, calibrate the accelerometer using the 6-O method [3]. Place the static tag in six orientations (each axis aligned to +1g and -1g) for ~10 seconds each. Calculate the vectorial sum ( \|a\| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2} ) for each orientation. Correct each axis with a two-level correction to ensure the vector sum equals 1.0 g [3].

- Tag Attachment:

- Choose an attachment method (e.g., leg-loop harness, backpack harness, glue) and position (e.g., back, tail, limb) that minimizes impact on the animal and is appropriate for the species [3] [9]. Note: Tag placement significantly affects the signal; standardize placement within a study and report it precisely [3].

- Set an appropriate sampling frequency. For general behaviours, the Nyquist-Shannon theorem states the frequency should be at least twice that of the fastest movement of interest. For short-burst behaviours (e.g., swallowing in birds), frequencies as high as 100 Hz may be needed, while for sustained behaviours (e.g., flight), 12.5 Hz may suffice [9].

- Ground-Truthing:

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Workflow for Behaviour Classification

- Data Pre-processing:

- Import raw acceleration data (x, y, z axes).

- Segment the data into windows. Common window lengths range from 1 to 10 seconds. A sensitivity analysis can be conducted to identify the optimal window and overlap for each behaviour [16].

- Apply filtering techniques if necessary (e.g., high-pass filter to remove static gravity component) [16].

- Feature Extraction:

- From each data window, calculate descriptive features for each axis and the vector norm. Common features include mean, standard deviation, variance, skewness, kurtosis, and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) coefficients to capture periodic signals [16].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Use the ground-truthed data to train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Convolutional Neural Network).

- Critical Step: To avoid overfitting and ensure the model generalizes, rigorously validate it using independent test sets. A robust method is to train the model on data from some individuals and test it on completely different, unseen individuals [15]. Performance metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC) should be reported for both training and test sets [16].

Figure 1: Workflow for classifying animal behaviour from accelerometer data using machine learning. Key validation and calibration steps are highlighted.

Estimating Energy Expenditure

Objective: To use Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) as a proxy for movement-based energy expenditure.

Background: The Vector of Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA), calculated as ( VeDBA = \sqrt{(x{dynamic})^2 + (y{dynamic})^2 + (z_{dynamic})^2} ), is strongly correlated with energy expenditure measured via respirometry across many vertebrate species [3] [14]. It represents the animal's movement-induced acceleration, excluding the static gravity component.

Protocol: Deriving Energy Expenditure Proxies

- Data Collection:

- Follow the calibration and attachment protocols described in Section 2.1. Note: Accuracy, tag placement, and attachment method critically affect signal amplitude and therefore VeDBA values. Upper and lower back-mounted tags can vary in DBA by 9%, and tail- versus back-mounted tags by 13% [3].

- Calculating VeDBA:

- Separate Static and Dynamic Acceleration: Use a high-pass filter (e.g., a running mean) to remove the static gravitational component (low-frequency) from the total acceleration, leaving the dynamic acceleration (high-frequency) due to movement.

- Compute VeDBA: For each data point, calculate the vector norm of the dynamic components from all three axes [3].

- Sampling Considerations for Energetics:

- For estimating overall energy expenditure over periods (e.g., a foraging trip), lower sampling frequencies (e.g., 1-10 Hz) are often sufficient [9].

- The combination of sampling frequency and sampling duration affects the accuracy of signal amplitude (and thus VeDBA) estimation. For short sampling durations, a sampling frequency of four times the signal frequency (twice the Nyquist frequency) is recommended for accurate amplitude estimation [9].

Detecting Reproductive and Life-History Events

Objective: To identify specific reproductive events (e.g., egg-laying, nesting, parturition) and monitor related behavioral changes.

Background: Characteristic behavioral patterns associated with reproductive events can be detected via accelerometers. For example, convolutional neural networks have been used to identify the egg-laying process in sea turtles [1].

Protocol: Identifying Reproductive Behaviors

- Define Behavioral Signature:

- For the target species, identify the unique sequence of postures and movements associated with the reproductive event (e.g., distinct body-shifting during egg-laying, increased nest-building activity, or specific resting patterns during pregnancy).

- Data Collection and Analysis:

- Deploy accelerometers on individuals during the known reproductive season.

- Use a supervised machine learning approach (as in Protocol 2) to train a model to recognize the specific behavioural signature of the reproductive event.

- Alternatively, for well-defined states like sustained rest (which may indicate incubation), simple thresholds on activity counts can be used. For instance, "naps" or sustained rest episodes can be defined as periods with zero activity lasting at least 10 minutes, not interrupted by activity longer than 2 minutes [17].

Table 1: Impact of methodological choices on accelerometer data outcomes. DBA refers to Dynamic Body Acceleration.

| Factor | Quantitative Impact | Experimental Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Calibration | DBA differences of up to 5% between calibrated and uncalibrated tags. | Humans walking at various speeds. | [3] |

| Tag Placement | 9% variation in DBA between upper/lower back; 13% variation between back/tail mounts. | Pigeons in wind tunnel; wild kittiwakes. | [3] |

| Sampling Frequency | 100 Hz needed for swallowing (28 Hz mean freq.); 12.5 Hz adequate for flight. | European pied flycatchers in aviaries. | [9] |

| Model Validation | 79% of reviewed studies (94/119) did not sufficiently validate for overfitting. | Systematic review of accelerometer-based behaviour classification. | [15] |

| Seasonal/Deployment Covariables | DBA varied by 25% between seasons. | Red-tailed tropicbirds with different tag types/attachments in different seasons. | [3] |

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for accelerometer studies in biologging.

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Application Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer Biologger | Measures acceleration in three perpendicular axes. Core sensor for data collection. | Select based on weight, battery life, memory, and sampling frequency capability. Critical for all applications. | |

| Calibration Platform | A stable, level surface used for the 6-O calibration method. | Ensures measurement accuracy, correcting for sensor error introduced during manufacturing. | [3] |

| Leg-Loop or Backpack Harness | A common method for attaching loggers to birds and mammals. | Standardizes tag position; choice affects signal and animal welfare. | [9] |

| Synchronized Video System | High-speed cameras for ground-truthing behaviours. | Provides labelled data essential for training and validating machine learning models. | [1] [9] |

| Machine Learning Pipeline (e.g., ACT4Behav) | Software for processing raw data, feature extraction, and model training. | Automates behaviour classification; pipelines can be tailored to specific species and behaviours. | [16] |

This application note outlines standardized protocols for employing accelerometers in wildlife biologging, emphasizing the critical importance of sensor calibration, standardized tag placement, appropriate sampling frequency, and rigorous machine learning validation [3] [15] [9]. The tables and workflow diagram provide a concise reference for researchers to design robust studies. Adhering to these guidelines ensures the collection of high-quality, comparable data, advancing our understanding of animal behaviour, energetics, and reproduction in a rapidly changing world.

The integration of multi-sensor biologging devices has revolutionized wildlife research, enabling an unprecedented, data-driven understanding of animal movement ecology, behavior, and physiology. While accelerometers have long been the cornerstone for classifying behavior and estimating energy expenditure, their fusion with GPS and magnetometer data provides a more comprehensive and accurate picture of an animal's movement path, orientation, and environmental context. This integration addresses limitations inherent in using any single sensor, allowing researchers to move from simple descriptions of what an animal is doing to richer explanations of how and why it navigates and interacts with its environment. This protocol details the methodologies for deploying and utilizing integrated sensor suites within the broader research objectives of wildlife biologging.

Hardware Integration and Sensor Specifications

The foundation of robust multi-sensor research is the careful selection and integration of hardware components that meet the physiological and behavioral constraints of the study species.

Integrated Multisensor Collar (IMSC) Design

The design of an Integrated Multisensor Collar (IMSC) must balance data quality with animal welfare. A successful field test on 71 free-ranging wild boar utilized a custom-designed collar with the following specifications [18]:

- Sensors: A "Thumb" Daily Diary tag equipped with a triaxial accelerometer, triaxial magnetometer, and a GPS receiver.

- Data Recording: Accelerometer and magnetometer data were recorded continuously at 10 Hz on a removable 32 GB MicroSD card. GPS fixes were scheduled at 30-minute intervals.

- Durability & Recovery: The collar design featured a integrated drop-off mechanism and VHF beacon, resulting in a 94% recovery rate and a 75% cumulative data recording success rate over a maximum logging duration of 421 days.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Biologging Materials

The following table details key hardware and analytical tools required for research employing integrated sensor suites.

Table 1: Essential Materials for Integrated Sensor Biologging Research

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| WildFi Tag | A state-of-the-art biologger featuring a 9-axis IMU (accelerometer, magnetometer, gyroscope), GPS capability, and WiFi data transmission. Its small size (25.95 x 17.85 x 0.6 mm) and light weight (1.28g) minimize animal disturbance [19]. |

| Daily Diary Tag | A data logger equipped with triaxial accelerometer and magnetometer sensors (e.g., LSM303DLHC or LSM9DS1), often custom-integrated with GPS units for long-term deployment on terrestrial mammals [18]. |

| Drop-off Mechanism | A critical component for collar recovery, often using a timed or remotely-triggered release system to ensure the device does not permanently encumber the animal [18]. |

| Calibration Jig | A setup to hold biologgers in a series of static orientations (the 6-O method) to correct for sensor inaccuracies and ensure measurement accuracy across devices [3]. |

| Machine Learning Classifier | A computational tool (e.g., Random Forest, Decision Trees) used to identify animal behaviors from complex, multivariate sensor data. One study achieved 85-90% accuracy in classifying six behaviors in wild boar [18] [19]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Acquisition

Standardized protocols for data collection and sensor management are vital for ensuring data quality and enabling cross-study comparisons.

Sensor Calibration Protocol

Accelerometer accuracy, tag placement, and attachment critically affect signal amplitude and can generate trends with no biological meaning. The following calibration protocol is recommended prior to deployment [3]:

- Objective: To correct for sensor measurement error and ensure the vector sum of the three acceleration channels is 1g when the unit is at rest.

- Procedure (6-O Method): Place the motionless biologger in six defined orientations where each of the three accelerometer axes is perpendicular to the Earth's surface, reading both -1g and +1g.

- Data Processing: For each axis, apply a two-level correction:

- A correction factor to ensure both absolute 'maxima' per axis are equal.

- A gain applied to both readings to convert them to be exactly 1.0g.

- Outcome: This calibration eliminates measurement error, which can result in DBA differences of up to 5% between calibrated and uncalibrated tags.

Determining Sampling Frequency

The appropriate sampling frequency is behavior-dependent and must be optimized to capture relevant signals without unnecessarily draining battery or storage.

Table 2: Accelerometer Sampling Frequency Guidelines Based on Behavioral Phenomena

| Behavioral Phenomenon | Recommended Minimum Sampling Frequency | Rationale & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Short-burst behaviors (e.g., swallowing in birds, prey capture) | 100 Hz [9] | Required to capture the high-frequency, transient signals (e.g., swallowing at a mean frequency of 28 Hz). |

| Rhythmic, sustained movement (e.g., flight in birds) | 12.5 Hz [9] | Lower frequencies are adequate to characterize the consistent waveform patterns of sustained locomotion. |

| General Principle (Nyquist-Shannon) | At least 2x the frequency of the fastest essential body movement [9] | Prevents signal aliasing. For short-burst behaviors, 1.4x the Nyquist frequency may be required. |

Field Deployment and Data Collection Workflow

The integration of multiple sensors creates a complex data collection pipeline. The following diagram outlines the standard workflow from deployment to data processing.

Diagram 1: Integrated Sensor Data Workflow

Data Analysis and Analytical Framework

The raw data from integrated sensors requires sophisticated analytical techniques to extract ecologically meaningful information.

Machine Learning for Behavioral Classification

Machine learning models can be trained to automatically identify behaviors from accelerometer data, a process that can be enhanced by magnetometer-derived headings [18].

- Protocol for Classifier Development:

- Ground-Truth Data Collection: Collect video footage (e.g., using infrared game cameras) synchronized with accelerometer data from animals in a controlled enclosure or natural setting.

- Data Labeling: Manually annotate the accelerometer data streams with specific behavioral classes (e.g., resting, walking, foraging) based on the video recordings.

- Feature Extraction: Calculate features (e.g., mean, variance, frequency-domain metrics) from windowed segments of the accelerometer and magnetometer data.

- Model Training & Validation: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest) on a subset of the labeled data and validate its accuracy on a withheld test set. One study on wild boar achieved 90% overall accuracy in identifying six behaviors [18].

Magnetic Heading Calibration and Dead-Reckoning

Magnetometers provide compass headings essential for dead-reckoning, but raw data requires tilt-compensation derived from accelerometer data [18].

- Protocol for Magnetic Heading Calculation:

- Tilt Compensation: Use the static acceleration (gravity) measured by the accelerometer to calculate the animal's pitch and roll.

- Heading Calculation: Apply a rotation matrix to the raw magnetometer data to correct for the animal's orientation, translating the measurements from the animal's frame of reference to the Earth's frame, thus yielding the true magnetic heading.

- Accuracy Assessment: Both laboratory and field tests have shown this method can produce magnetic headings with median deviations from ground truth of less than 2° [18].

- Dead-Reckoning Path Reconstruction: Integrate the estimated speed (from accelerometer-derived gait analysis or GPS) with the magnetic heading to reconstruct fine-scale movement paths between intermittent GPS fixes, providing a wealth of information on animal movement and habitat use [18].

A Novel Framework for Inferring Animal-Environment Relationships

A machine learning-based analytic framework can quantify the influence of environmental variables on multivariate animal movement [20].

- Protocol:

- Variable Selection: Define a set of multivariate movement descriptors (e.g., from accelerometers and GPS) and a target environmental variable (e.g., grass biomass, time since milking).

- Model Building: Instead of predicting movement from the environment, build a model (e.g., Random Forest Regression) to predict the environmental variable from the full set of movement data.

- Quantifying Influence: The fit of this prediction (e.g., R²) is taken as a metric for how much of the variation in the environmental variable is reflected in the animal's movement. A case study on dairy cows showed that 37% of the variation in grass availability and 33% of time since milking was reflected in cow movement patterns [20].

Application in Predator Energetics and Conservation

Integrating multisensor data is particularly powerful for studying costly behaviors like predation and for understanding animal responses to global change.

- Energetic Landscapes: By combining DBA from accelerometers (a proxy for energy expenditure) with GPS data on movement paths, researchers can map "energetic landscapes." This reveals how habitat heterogeneity and prey distribution influence the energy costs of foraging, which is crucial for predicting predator performance under changing conditions [14].

- Social Flexibility: Biologging can reveal nuanced social foraging strategies that are difficult to observe directly. Strategic tagging within and between social groups is needed to capture intra-group interactions and hunting roles, which may be more flexible than previously described [14].

- Optimizing Data Transmission: To overcome battery life constraints, machine learning models (e.g., decision trees) can be run on-board the biologger to recognize specific behaviors and trigger selective data transmission. This approach can reduce the volume of transmitted data by 20% with minimal precision loss, potentially more than doubling the operational lifespan of the device [19].

From Raw Data to Actionable Insights: Methodologies for Behavior and Energetics

The use of accelerometers in wildlife biologging has revolutionized the study of animal behavior, enabling researchers to remotely monitor and interpret fine-scale activities in species ranging from terrestrial mammals to marine birds [15] [21]. A critical step in this process involves using machine learning (ML) to classify raw sensor data into meaningful behavioral categories. The choice between supervised and unsupervised ML workflows represents a fundamental methodological decision, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications [22] [23] [24]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these approaches within wildlife biologging research, framed specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals utilizing accelerometer data.

Comparative Workflow Analysis

Table 1: High-level comparison of supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches for behavioral identification.

| Feature | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Requirement | Pre-labeled dataset with known behaviors [15] | Raw, unlabeled data [22] |

| Primary Output | Classification into predefined behavioral classes [25] | Discovery of novel behavioral motifs or clusters [22] |

| Best Suited For | Testing specific hypotheses about known behaviors [24] | Exploratory analysis to discover unknown behavioral repertoires [22] |

| Data Preparation | Requires intensive labeling effort (e.g., field observations) [25] | No labeling needed; relies on pattern detection [22] |

| Key Advantage | Direct, interpretable link to specific behaviors [25] | Eliminates observer bias; can reveal novel behaviors [22] |

| Major Challenge | Risk of overfitting if not properly validated [15] | Functional interpretation of clusters requires validation [22] |

| Validation | Performance metrics on independent test set [15] | Biological relevance and repeatability of motifs [22] |

Supervised Machine Learning Workflow

Supervised learning relies on training models with accelerometer data that has been pre-labeled with corresponding behaviors, often obtained through direct observation [25] [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Collection and Labeling

- Deploy accelerometers on study subjects, ensuring proper attachment and alignment of sensor axes (e.g., surge, sway, heave) [24].

- Conduct simultaneous behavioral observations to create a labeled ground-truth dataset. Record the onset, duration, and type of behavior (e.g., lying, feeding, walking, running) [25].

- Synchronize sensor data logs and observation timestamps precisely.

Step 2: Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

- Segment the continuous raw acceleration data into fixed-length windows (e.g., 3-5 seconds). Overlap windows by 50% to capture complete behavioral sequences [15].

- Calculate summary statistics (features) for each axis and the vector norm (e.g., VeDBA - Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration) within each window. Common features include:

- Handle data imbalance by employing techniques like oversampling minority behavioral classes or using balanced performance metrics [25].

Step 3: Model Training with Rigorous Validation

- Split the labeled dataset into three independent subsets:

- Training Set (~60%): Used to train the model.

- Validation Set (~20%): Used to tune model hyperparameters.

- Test Set (~20%): Used only for the final, unbiased evaluation of model performance [15].

- Train multiple classifier algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Discriminant Analysis, Support Vector Machines) on the training set [25] [24].

- Select the best model based on performance on the validation set. Avoid making decisions based on the test set to prevent data leakage and overoptimistic performance estimates [15].

Step 4: Model Evaluation and Deployment

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Use metrics appropriate for imbalanced data (e.g., balanced accuracy, F1-score) [25].

- Deploy the trained model to classify behaviors in new, unlabeled accelerometer data from wild individuals.

Figure 1: Supervised learning workflow for training a validated animal behavior classifier.

Unsupervised Machine Learning Workflow

Unsupervised learning algorithms identify recurring behavioral motifs from pose-tracking or accelerometry data without pre-labeled examples, reducing observer bias and uncovering novel patterns [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Pose Estimation from Video Data (If Applicable)

- Acquire high-resolution video recordings of the study subjects.

- Use pose-estimation tools like DeepLabCut or SLEAP to track the coordinates (X, Y) of key body parts (e.g., nose, ears, limbs, tail base) across all video frames [22] [26].

Step 2: Feature Engineering and Dimensionality Reduction

- Engineer features from the keypoint coordinates to represent body dynamics. Common methods include:

- B-SOiD: Calculates distances, angles, and speeds between keypoints over short time windows (e.g., 100 ms) [22].

- BFA: Computes a broader set of features including distances, angles, accelerations, and areas, using a rolling time window [22].

- Egocentric Alignment: (VAME, Keypoint-MoSeq) Realigns keypoints to a reference point on the animal's body to remove the effect of overall orientation [22].

- Reduce dimensionality to mitigate noise and highlight core patterns. Techniques include:

- UMAP (B-SOiD) for non-linear reduction.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Keypoint-MoSeq) for linear reduction.

- Variational Autoencoders (VAME) for non-linear reduction of sequential data [22].

Step 3: Behavioral Clustering or Segmentation

- Apply a clustering algorithm to the reduced feature space to identify discrete behavioral motifs.

- HDBSCAN (B-SOiD): Density-based; automatically determines the number of clusters and handles noise [22].

- K-means (BFA): Centroid-based; requires the user to predefine the number of clusters (k) [22].

- Hidden Markov Models (HMM) (VAME, Keypoint-MoSeq): Models behavior as a sequence of hidden states, capturing temporal dependencies [22].

Step 4: Motif Interpretation and Validation

- Interpret the resulting clusters by visualizing the original video frames associated with each discovered motif.

- Label the motifs with biologically meaningful names (e.g., "grooming," "rearing") based on the observed postures and movements [22].

- Validate the biological relevance of the motifs by consulting ethograms or assessing their predictive power for experimental conditions.

Table 2: Comparison of unsupervised learning algorithms for behavioral motif discovery.

| Algorithm | Clustering Method | Key Feature Engineering | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-SOiD [22] | HDBSCAN | UMAP on distances, angles, speeds | Automatic cluster discovery; handles noise and arbitrary shapes. | UMAP may make data points appear artificially similar. |

| BFA [22] | K-means | Large feature set (distances, angles, areas) in rolling window. | Straightforward to add new, user-defined features. | Struggles with non-spherical clusters; requires predefined cluster number (k). |

| VAME [22] | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Egocentric alignment + Variational Autoencoder | Captures complex temporal dynamics of behavior. | Hard to relate latent space back to original data; difficult to transfer models. |

| Keypoint-MoSeq [22] | Autoregressive HMM (AR-HMM) | Egocentric alignment + PCA | Robust to pose estimation noise; models temporal dependencies. | Linear PCA may be less powerful for highly complex data. |

Figure 2: Unsupervised learning workflow for discovering novel behavioral motifs from tracking data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential tools and software for implementing ML workflows in behavioral identification.

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer [15] [24] | Sensor Hardware | Measures surge, sway, and heave acceleration; primary data source for supervised learning and some unsupervised approaches. |

| DeepLabCut / SLEAP [22] | Pose-Estimation Software | Tracks animal body part coordinates from video footage; creates input data for unsupervised learning algorithms. |

| B-SOiD, BFA, VAME, Keypoint-MoSeq [22] | Unsupervised Learning Algorithms | Software packages for discovering behavioral motifs from pose-tracking or accelerometry data without labels. |

| Random Forest / Discriminant Analysis [25] [24] | Supervised Learning Algorithms | Classifier models used to assign predefined behavioral labels to new accelerometer data. |

| Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) [24] | Energetic Proxy | A derived metric from accelerometer data used to estimate energy expenditure associated with classified behaviors. |

| NU9056 | NU9056, MF:C6H4N2S4, MW:232.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Survodutide | Survodutide, CAS:2805997-46-8, MF:C192H289N47O61, MW:4232 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within wildlife biologging research, accelerometers have revolutionized our ability to study animal movement and behavior remotely. However, the transformation of raw sensor data into meaningful behavioral classifications hinges on robust foundational practices. This protocol details the critical roles of ethograms and video validation in captive settings for training and validating machine learning models that interpret accelerometer data. These steps are essential for ensuring that computational inferences accurately reflect biological reality, thereby enhancing the reliability of findings in movement ecology and conservation physiology.

Section 1: The Ethogram as the Foundational Framework

An ethogram is a comprehensive catalog of species-specific behaviors, providing the standardized vocabulary and definitions required for consistent behavioral scoring. In the context of biologging, it forms the basis for the labeled data used to train supervised machine learning models [27] [28].

Table 1: Key Components of an Effective Ethogram for Biologging Studies

| Component | Description | Application to Accelerometer Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Categories | Distinct, mutually exclusive definitions of behaviors (e.g., resting, foraging, locomotion). | Provides the target labels for supervised machine learning models [28]. |

| Manipulation Behaviors | Specific actions directed at objects or the environment (e.g., oral, tactile) [27]. | Helps link specific acceleration signatures to precise physical actions. |

| Social Context | Notes on whether a behavior is performed in solitude, affiliation, or aggression [27]. | Aids in interpreting variation in acceleration data that is socially modulated. |

| Coding Protocol | Rules for defining the start and end of a behavioral state and its intensity. | Ensures consistent human labeling, which improves model generalizability. |

Protocol 1.1: Developing and Implementing a Captive Ethogram

- Literature Review: Compile potential behaviors from existing ethograms for the study species or related taxa.

- Pilot Observation: Conduct unstructured observations in the captive setting to identify and define common, species-typical behaviors not reported in the literature.

- Define and Refine: Create discrete, objective definitions for each behavior to minimize observer subjectivity. The ethogram should be sensitive enough to capture the full range of natural behaviors [27].

- Incorporate Individual Variation: Account for individual differences in behavior patterns or preferences, as a "one size fits all" approach may not capture the full behavioral repertoire [27].

Section 2: Video Validation and Data Collection Protocols

Video recording provides the ground-truth data that is synchronized with accelerometer traces, enabling the direct correlation of specific behaviors to their unique kinematic signatures.

Table 2: Welfare Indicators Assessable via Remote Video in a Captive Setting

| Domain of Welfare | Assessable via Still Images | Assessable via Video Only |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | Body condition score | - |

| Physical Environment | Sweating excessively | Shivering, wet from rain, huddling |

| Health | Body posture, coat condition, wounds, hoof condition | Gait at walk/trot/canter, weakness, respiratory effort |

| Behavioral Interactions | Specific quantifiable behaviors (e.g., feeding, resting), proximity to others | Qualitative Behavioral Assessment (e.g., dull, relaxed, anxious, playful) [29] |

Protocol 2.1: Synchronized Video-Accelerometer Data Collection

- Equipment Setup:

- Use multiple camera traps or fixed video cameras to cover the enclosure from different angles, enabling observation in complex habitats like woodlands [29].

- Ensure the accelerometer logging rate (e.g., 25-100 Hz) is sufficient to capture the behaviors of interest and is time-synchronized with the video recording equipment.

- Data Recording:

- Record video footage during periods of varied activity. For a comprehensive dataset spanning different contexts, long-term archival of videos collected over months or years can be highly valuable [27].

- Maintain a record of individual animal identities, as many species can be individually identified from video [29].

- Behavioral Annotation:

- Use video annotation software (e.g., The Observer XT, BORIS) to label the onset, offset, and type of behavior for each individual according to the ethogram [16].

- This process generates the ground-truth dataset used for model training.

Section 3: From Data to Model – An Integrated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete pipeline for developing a behavior classification model, integrating ethograms and video validation with accelerometer data processing.

Experimental Protocol: Model Training and Critical Validation

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in recent studies on diverse taxa, from dairy cattle to squid [30] [31] [32].

Protocol 3.1: Training and Validating a Behavior Classification Model

- Data Pre-processing:

- Segmentation: Divide the continuous accelerometer data stream into fixed-length or variable-length windows. Sensitivity analysis can be conducted to identify the optimal window segmentation for each behavior [16].

- Feature Extraction: For classical machine learning, calculate summary statistics (e.g., mean, variance, covariance) for each axis within a window. Alternatively, use deep learning models that can learn features directly from the raw data [28].

- Model Training:

- Use the video-annotated behaviors as the target labels (Y) and the extracted accelerometer features or raw data as the input (X).

- Explore different algorithms. Recent benchmarks suggest deep neural networks can outperform classical methods like random forests across a range of species [28].

- Rigorous Validation (Critical to Prevent Overfitting):

- Data Splitting: Partition data into independent training, validation, and test sets. A common but flawed practice is to split data randomly from all individuals, which can mask overfitting. Instead, use a "leave-one-individual-out" or "by-farm" approach where the test set contains data from animals not seen in the training set. This provides a more realistic estimate of model performance on new data [15] [32].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using metrics such as Accuracy, F1-Score, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) [16]. A significant performance drop between the training and test sets indicates overfitting [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | The primary sensor measuring acceleration in three spatial dimensions, attached to the animal to capture movement kinetics [3]. |

| Camera Traps / Video System | Provides the ground-truth video footage for behavioral annotation; essential for validation in complex or inaccessible enclosures [29]. |

| Magnetometer-Magnet Coupling | A supplementary method where a magnetometer sensor detects movements of a magnet attached to a peripheral appendage (e.g., jaw, fin), enabling direct measurement of specific behaviors like foraging or ventilation [30]. |

| Annotation Software (e.g., BORIS, The Observer) | Software for systematically scoring and labeling behaviors from video footage based on the custom ethogram, generating the labeled dataset. |

| Computational Pipelines (e.g., ACT4Behav, vassi) | Specialized software packages that help standardize the process of feature extraction, model training, and validation for accelerometer data [16] [33]. |

| Calibration Rig | A defined setup (e.g., a "6-O method" placing the tag motionless in six orientations) to correct for sensor inaccuracies and ensure data comparability across tags and deployments [3]. |

| GLP-1(7-36), amide acetate | GLP-1(7-36), amide acetate, MF:C151H230N40O47, MW:3357.7 g/mol |

| Sarcosine-13C3 | Sarcosine-13C3, MF:C3H7NO2, MW:92.072 g/mol |

Ethograms and video validation are not merely preliminary steps but are integral to the entire lifecycle of a biologging study. They provide the essential link between the complex physical signals recorded by accelerometers and the biological reality of animal behavior. By adhering to the detailed protocols for ethogram development, synchronized data collection, and rigorous model validation outlined in this document, researchers can build more reliable, generalizable, and biologically meaningful models to decipher the secrets of animal lives from their movement data.

Within the field of wildlife biologging, accurately measuring the energy expenditure of free-ranging animals is crucial for understanding their ecology, behavior, and physiology. The use of accelerometers has emerged as a powerful method for estimating energy expenditure, with Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) serving as a key proxy. This approach is grounded in the principle that the dynamic component of acceleration is a reflection of movement-based work, which in turn correlates with energy consumption. These Application Notes and Protocols detail the methodologies for employing DBA in wildlife studies, providing a standardized framework for researchers.

Understanding Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA)

Dynamic Body Acceleration is a metric derived from accelerometer data that quantifies the high-frequency, movement-induced acceleration of an animal's body, excluding the static acceleration due to gravity. It serves as a proxy for energy expenditure based on the premise that body movement requires mechanical work, which is linked to metabolic cost through muscle efficiency [34]. Two primary calculations are prevalent in the literature:

- Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA): Calculated as the sum of the absolute values of the dynamic acceleration from the three orthogonal axes (X, Y, Z) [35] [36].

- Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA): Calculated as the vector norm of the dynamic acceleration from the three axes [37] [36].

A comparative study on humans and several other animal species found that both ODBA and VeDBA were good proxies for the rate of oxygen consumption (VOâ‚‚), with ODBA accounting for slightly but significantly more of the variation. However, VeDBA is recommended in situations where consistent accelerometer orientation cannot be guaranteed [36].

Key Research Findings and Quantitative Data

The relationship between DBA and energy expenditure has been validated across a range of species using doubly labelled water (DLW) and heart rate as gold-standard measures. The following table summarizes key validation studies.

Table 1: Validation of DBA as a proxy for energy expenditure across species.

| Species | DBA Type | Validation Method | Key Finding (R²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thick-billed murres (Uria lomvia) | PDBA | Doubly Labelled Water | R² = 0.73 across all modes; Model with separate coefficients for flight was best (R²=0.81) | [34] |

| Pelagic cormorants (Phalacrocorax pelagicus) | ODBA & VeDBA | Doubly Labelled Water | Both ODBA and VeDBA correlated with mass-specific energy expenditure (R² = 0.91) | [37] |