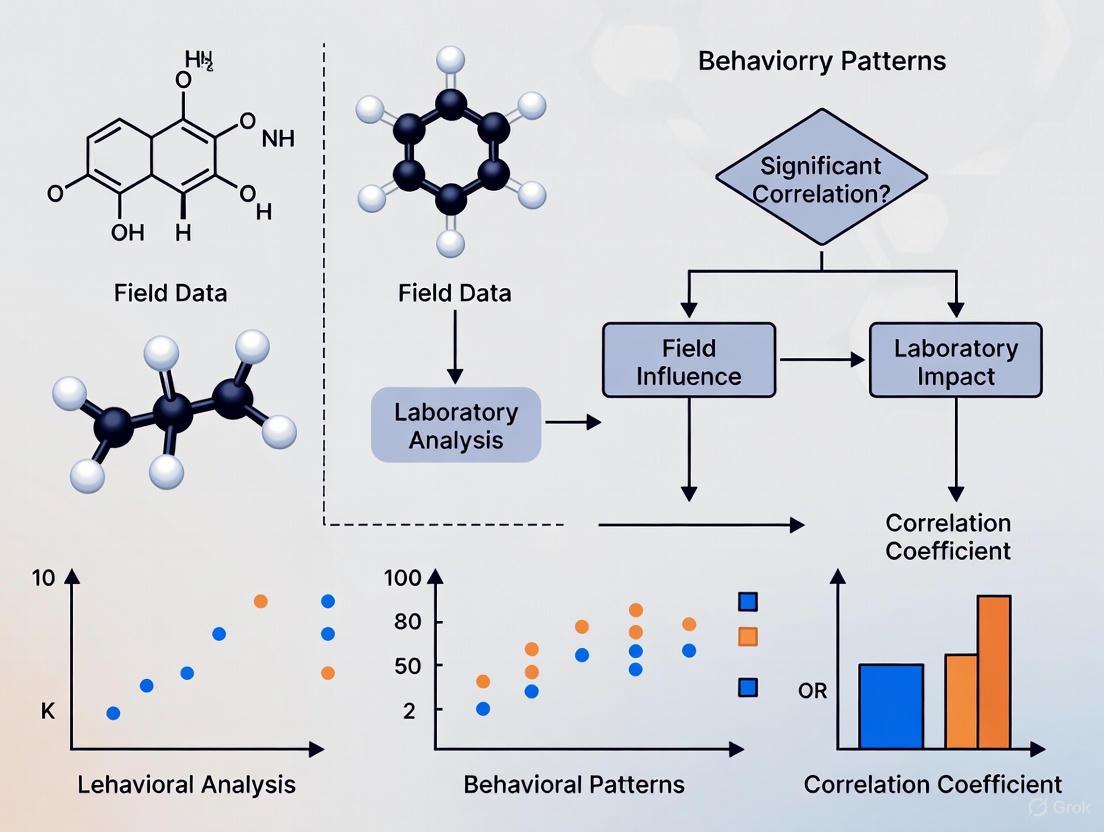

Bridging the Gap: Understanding the Correlation Between Field and Laboratory Behavior for Robust Scientific Discovery

This article examines the critical relationship between field and laboratory research environments, a central concern for researchers and drug development professionals.

Bridging the Gap: Understanding the Correlation Between Field and Laboratory Behavior for Robust Scientific Discovery

Abstract

This article examines the critical relationship between field and laboratory research environments, a central concern for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles defining lab and field settings, analyzing the persistent 'lab-field behavior gap' and its implications for external validity. The review details methodological frameworks, including hybrid models like 'lab-in-the-field' experiments, that integrate the control of the lab with the realism of the field. We provide actionable strategies for troubleshooting common challenges such as artificial environments and limited generalizability, and offer a comparative analysis for validating and selecting the appropriate research design. The synthesis underscores that a strategic, complementary use of both approaches is paramount for generating findings that are both scientifically rigorous and translatable to real-world biomedical and clinical applications.

The Foundational Divide: Defining Laboratory and Field Research Environments

Core Definitions at a Glance

| Feature | Controlled Laboratory Setting | Naturalistic Field Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | To establish causal relationships by isolating and manipulating variables in a pure form. [1] | To understand behavior and processes in their real-world context with high ecological validity. [2] [3] |

| Environment | Highly artificial and controlled; all non-essential variables are eliminated or held constant. [1] [3] | The natural, real-world environment where the phenomenon of interest naturally occurs. [2] [4] |

| Key Characteristic | Control and Isolation of variables; use of standardized procedures. [1] [3] | Naturalistic Observation; study of complex, real-world interactions. [1] [3] |

| Data Collection | Often precise and easy to collect using specialized equipment; high internal validity. [3] | Can be complex due to uncontrolled variables; high external validity. [2] [3] |

| Ideal For | Testing hypotheses about cause-and-effect; fundamental discovery research. [1] | Testing the efficacy of interventions in practice; studying behavior in authentic contexts. [2] [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: The True Laboratory Experiment

This methodology is the gold standard for establishing causality and is foundational in early-stage research, such as preclinical drug discovery. [1] [6]

- 1. Hypothesis & Design: Define a clear, testable hypothesis. Determine the independent variable (the cause you will manipulate) and the dependent variable (the effect you will measure). [1]

- 2. Random Assignment: Recruit participants and randomly assign them to either a treatment group or a control group. This is critical for creating equivalent groups and minimizing the influence of confounding variables. [1] [5]

- 3. Implementation of Control: The treatment group receives the intervention (e.g., a new drug candidate), while the control group receives a placebo or the current standard of care. All other conditions (e.g., temperature, noise, instructions) are kept identical for both groups. [1]

- 4. Blinding: Where possible, implement a single-blind (participants don't know their group) or double-blind (both participants and experimenters don't know) design to prevent bias. [5]

- 5. Data Collection & Analysis: Measure the dependent variable using standardized instruments and procedures. Compare outcomes between the treatment and control groups using statistical analysis to determine if the manipulation caused a significant effect. [1]

Protocol 2: The Field Experiment

This approach bridges the controlled lab and the messy real world, often used to test policies or interventions in real-life contexts, such as in implementation science or behavioral economics. [2] [5]

- 1. Define Real-World Problem: Identify a specific question that requires a natural context (e.g., "Does a new school mentoring program reduce student arrests?"). [2]

- 2. Partner with a Real-World Organization: Collaborate with a school, company, hospital, or NGO to gain access to the natural environment and subject pool. [2]

- 3. Randomization in the Field: Randomly assign units (e.g., schools, clinics, districts) to either receive the intervention (treatment group) or continue with business as usual (control group). This maintains the power of causal inference. [2] [5]

- 4. Naturalistic Implementation: Implement the intervention or procedure within the regular flow of the environment. A key feature of natural field experiments is that participants are often unaware they are part of a study. [2] [4]

- 5. Outcome Measurement: Collect data on relevant outcomes. This may involve administrative data (e.g., arrest records, graduation rates), surveys, or direct observation, while minimizing disruption to the natural setting. [2]

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Choosing Your Research Environment

Q: My primary goal is to test a fundamental cause-and-effect relationship with high internal validity. Which setting should I prioritize? A: The Controlled Laboratory Setting is the definitive choice. Its high level of control allows you to isolate variables and establish causality with confidence. [1]

Q: I need to know if my intervention will work in the complex, "messy" real world. What is the best approach? A: A Naturalistic Field Setting is essential. It provides the ecological validity needed to see how your intervention performs amidst all the variables of real life. [2] [3]

Q: Can I combine these two approaches? A: Absolutely. A mixed-method approach is highly effective. You can first establish causality in the lab and then test the generalizability of the finding in a field experiment. This balances strengths and weaknesses. [1] [4]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lab results fail to replicate in real-world studies. | Limited Generalizability: The controlled lab environment stripped away key contextual factors present in the real world. [3] | Follow a sequential approach. After a positive lab result, immediately design a field experiment to test the finding in a natural context with a relevant population. [1] [4] |

| Participants in my study are altering their behavior because they know they're being observed (Hawthorne Effect). | Artificial Environment & Demand Characteristics: Participants are reacting to the research setting itself. [2] [3] | Move towards a natural field experiment where participants are unaware they are part of a study, allowing for the observation of authentic behavior. [2] [4] |

| I cannot randomly assign participants for ethical or practical reasons. | Limitations of True Experimental Design in complex real-world institutions. [5] | Consider a Quasi-Experimental Design. These designs use manipulation but lack random assignment, instead relying on existing groups (e.g., comparing two different clinics). [5] [7] |

| There are too many uncontrolled variables in the field, making it hard to pinpoint what caused an effect. | Lack of Control inherent in field settings. [3] | Strengthen the design through randomization at the group level (cluster randomization) and carefully measure potential confounding variables to statistically control for them in your analysis. [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Protocols | Ensures consistency and replicability by providing identical procedures, instructions, and conditions for all participants. [1] [3] | Critical in lab experiments to isolate the manipulated variable. Also used in field settings to ensure the intervention is delivered uniformly. |

| Placebo | An inert substance or procedure that is indistinguishable from the active intervention. Serves as the baseline for comparison in the control group. [2] | Foundational in clinical drug trials (lab and field) to account for psychological and physiological placebo effects. [6] |

| Random Assignment Software | Algorithmically assigns participants to control or treatment groups to minimize selection bias and create statistically equivalent groups. [1] | A non-negotiable component of true experiments in both lab and field settings to support causal claims. |

| Blinding (Masking) Protocols | Procedures where participants (single-blind) and/or researchers (double-blind) are unaware of group assignments to prevent bias in reporting and analysis. [5] | Extensively used in high-stakes lab and clinical research, especially when outcomes can be subjective. |

| Validated Psychometric Scales | Questionnaires and tests that have been statistically evaluated for reliability and accuracy in measuring constructs like attitudes, preferences, or behaviors. [1] | Used across both settings to quantitatively measure complex dependent variables. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval | A mandatory ethical review to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects. | Required for all studies involving human subjects. Special scrutiny is given to field experiments where informed consent may be compromised. [2] |

Core Concepts: Your Technical Support Hub

What are internal and external validity?

Internal Validity is the degree of confidence that the causal relationship you are testing is not influenced by other factors or variables. It answers the question: "Is my study telling me what I think it is?" [8] [9] [10]. An study with high internal validity allows you to state that the manipulation of your independent variable (e.g., a new drug dosage) is most likely the cause of any observed change in your dependent variable (e.g., reduced symptom severity).

External Validity is the extent to which your results can be generalized to other contexts, such as different populations, settings, or treatment variables [8] [10]. It addresses the question: "Will these findings apply to other populations or real-world practice?" [9] [11]. A subtype of external validity, Ecological Validity, specifically examines whether study findings can be generalized to real-life situations and settings [11] [10].

What is the fundamental trade-off between them?

There is often a trade-off between internal and external validity [12] [13] [10]. Maximizing internal validity typically requires a highly controlled environment, such as a laboratory, which can make the research conditions artificial and less representative of real-world situations. Conversely, conducting research in a real-world (field) setting to increase external validity introduces numerous extraneous variables that are difficult to control, potentially compromising internal validity [12] [13].

- Laboratory Research: Tends to be high in internal validity due to controlled environments and standardized procedures, but lower in external validity because the artificial conditions may not reflect real-world complexities [12] [3] [13].

- Field Research: Tends to be higher in external validity as it occurs in natural contexts, preserving the naturalness of the setting, but lower in internal validity due to the lack of control over extraneous variables [12] [3] [13].

However, some evidence suggests this trade-off may not be absolute. One analysis found no clear difference in internal validity (as measured by risk of bias) between highly controlled (explanatory) and real-world (pragmatic) trials, indicating that with careful design, both can be achieved [14].

Why is internal validity considered a prior indispensable condition?

Internal validity is the prior and indispensable consideration [9]. If a study lacks internal validity, you cannot draw trustworthy conclusions about the cause-and-effect relationship within the study itself. Without confidence in the study's internal results, the question of whether those results can be generalized to other contexts (external validity) becomes irrelevant [8] [9]. As such, establishing internal validity is the first critical step.

Troubleshooting Guides: Threats and Solutions

Guide 1: Identifying and Mitigating Threats to Internal Validity

Threats to internal validity are factors that can provide alternative explanations for your results, undermining the causal link you are investigating [10].

| Threat | Description | Example in Drug Development | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Unanticipated external events that occur during the study and influence the outcome. [10] | A change in clinical practice guidelines partway through a trial. | Use a controlled laboratory environment where possible. |

| Maturation | Natural psychological or biological changes in participants over time. [10] | Natural progression of a disease or placebo effect. | Include a control group that undergoes the same time passage. |

| Testing | The effect of taking a pre-test on the scores of a post-test. [10] | Patients becoming familiar with a cognitive assessment tool. | Use different forms of the test or counterbalance presentation. |

| Selection Bias | Systematic differences in participant composition between groups at baseline. [10] | Volunteers for a new therapy are more health-conscious. | Use random assignment to treatment and control groups. [9] |

| Attrition | Loss of participants from the study, which can bias the final sample. [10] | Patients experiencing side effects dropping out of a drug trial. | Use intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis and track all participants. |

| Instrumentation | Changes in the calibration of the measurement instrument or tool over time. [10] | Upgrading the software of a lab analyzer mid-study. | Standardize measurement tools and calibrate equipment regularly. |

Guide 2: Identifying and Mitigating Threats to External Validity

Threats to external validity are factors that limit the ability to generalize your findings beyond the specific conditions of your study [10].

| Threat | Description | Example in Drug Development | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testing Interaction | The pre-test itself sensitizes participants to the treatment, making them unrepresentative. [10] | A pre-screen questionnaire makes patients hyper-aware of symptoms. | Use a Solomon four-group design or avoid pre-tests when possible. |

| Sampling Bias | The study sample differs in important ways from the target population. [10] | Recruiting only from academic hospitals, excluding rural populations. | Use random sampling from the broadest possible population. [9] |

| Hawthorne Effect | Participants change their behavior because they know they are being studied. [10] | Patients in a trial may adhere to medication better due to increased attention. | Use a control group that receives equal attention but not the active treatment. |

| Artificial Environment | The controlled setting of the lab does not reflect real-world conditions. [3] [11] | A drug tested in a strict lab protocol may not work the same in a home setting. | Conduct follow-up field studies or pragmatic trials in real-world settings. [12] [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Balancing Validity

Protocol 1: The Sequential Confirmatory Workflow

This methodology uses a multi-stage approach to first establish causality and then test generalizability, directly addressing the core trade-off [12] [10].

Objective: To establish a causal relationship with high confidence and then determine its applicability in real-world practice. Rationale: This protocol acknowledges that no single study can maximize all forms of validity simultaneously and instead spreads the effort across linked studies.

Steps:

- Controlled Laboratory Experiment:

- Design: A tightly controlled, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

- Setting: A laboratory or specialized research facility.

- Goal: To achieve high internal validity by manipulating the independent variable and controlling for extraneous variables. The objective is to answer "Can the intervention work under ideal conditions?" [12] [14].

- Outcome: A preliminary causal relationship is established.

- Field Experiment or Pragmatic Trial:

- Design: A more flexible trial designed to test the intervention in a routine practice setting.

- Setting: Real-world environments such as clinics, hospitals, or community settings.

- Goal: To assess external validity and ecological validity. The objective is to answer "Does the intervention work in routine care?" [12] [14].

- Outcome: The generalizability of the laboratory findings is evaluated, providing evidence for real-world application.

Protocol 2: The Correlational-to-Experimental Bridge

This protocol is particularly relevant for field research on behavior correlation, where direct manipulation of variables may be unethical or impractical [13].

Objective: To use non-experimental field observations to generate hypotheses that are later tested with experimental methods. Rationale: Correlational studies often have high external validity but low internal validity. This protocol uses them as a starting point for building a more complete, causal understanding.

Steps:

- Field Correlational Study:

- Design: A non-experimental study where the researcher measures two variables in a natural setting with little to no control over extraneous variables [13].

- Method: Naturalistic observation, surveys, or using existing records.

- Goal: To describe the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables in a real-world context. This approach is high in external validity [13].

- Outcome: A statistical relationship (correlation) is identified, which can be used to predict scores on one variable based on another.

Causal Hypothesis Generation:

- Based on the observed correlation, a hypothesis about a potential causal relationship is formed.

Laboratory or Field Experiment:

- An experiment is designed to test the causal hypothesis by manipulating the independent variable.

- Goal: To establish internal validity and determine if the relationship is causal.

- Outcome: If the experimental study (high in internal validity) and the correlational study (high in external validity) both support the theory, researchers can have more confidence in its overall validity [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential methodological "reagents" for designing valid and reliable research.

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Random Assignment | Randomly distributes confounding variables among treatment and control groups, making them comparable. This is a primary tool for increasing internal validity. [9] | Essential for laboratory experiments and explanatory clinical trials. |

| Random Sampling | Selects participants from a population such that every member has an equal chance of being included. This creates a representative sample, increasing external validity. [9] | Used in survey research and large-scale field studies to ensure generalizability. |

| Control Group | Provides a baseline against which to compare the treatment group. Any difference in outcomes can more confidently be attributed to the experimental manipulation. [12] | A cornerstone of laboratory research and RCTs to establish causality. |

| Blinding (Single/Double) | Prevents participants (single-blind) and/or researchers & participants (double-blind) from knowing who is in the treatment or control group. Reduces performance and detection bias. [11] | Critical in clinical drug trials to prevent placebo effects and biased observations. |

| Standardized Procedures | Ensures that all participants are treated in the same way and all conditions are controlled for consistency. This minimizes the influence of confounding variables. [3] | Used in both lab and field research to enhance reliability and internal validity. |

| Broad Inclusion Criteria | Using minimal restrictions on who can participate in a study. This makes the study population more closely resemble real-life patients, thereby increasing external validity. [8] | A key feature of pragmatic trials and effectiveness research. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: If I have to sacrifice one for the other, which should it be?

Internal validity is the prior and indispensable consideration [9]. It is more critical to have a study that provides trustworthy answers about the specific causal relationship under investigation than to have a study with generalizable but potentially incorrect findings. You cannot generalize invalid results.

Q2: How can the PRECIS-2 tool help me design a better trial?

The PRECIS-2 (PRagmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary) tool helps trial designers visualize where their study sits on the spectrum from explanatory (focused on internal validity under ideal conditions) to pragmatic (focused on external validity in routine care) [14]. It does not judge a design as good or bad but ensures that the design choices align with the stated purpose of the trial. This helps in consciously balancing validity concerns from the very beginning.

Q3: My lab study has high internal validity but my manager questions its real-world relevance. How do I respond?

This is a common and valid concern. You can respond by:

- Acknowledging the Limitation: Clearly state that laboratory studies are designed to establish efficacy (whether it can work) under controlled conditions, which inherently limits effectiveness (whether it does work in the real world) [12] [14].

- Explaining the Strategic Rationale: Argue that this is often a necessary first step. Establishing a clear causal relationship in the lab provides the strong scientific foundation required before investing in more costly and complex field studies [10].

- Proposing the Next Step: Recommend a follow-up pragmatic or field study to directly test the applicability of your findings in a real-world context, thereby building a complete evidence base [12] [14].

Q4: Does "correlation does not imply causation" mean correlational research is invalid?

No, it does not mean correlational research is invalid. It means that a correlation between two variables alone does not allow you to conclude that one variable causes the other. This is due to problems like directionality (unclear which variable causes the other) and the third-variable problem (a separate, unmeasured variable causes both) [13]. Correlational research is extremely valuable for describing relationships and making predictions, especially when experimental research is impossible or unethical. It is high in external validity and provides the foundational observations that often lead to experimental hypotheses [13].

FAQ: Defining the Lab-Field Gap

What is the lab-field behavior gap? The lab-field behavior gap refers to the phenomenon where results, behaviors, or model performances observed in controlled laboratory environments fail to replicate or generalize to real-world (field) settings. This disconnect arises because laboratory settings cannot fully capture the complexity, variability, and contextual influences of natural environments [15] [16] [17].

In which research domains is this gap observed? This gap is a cross-disciplinary challenge, documented in:

- Psychology and Behavioral Science: Known as the "intention-behavior gap," where individuals' intentions do not reliably translate into actual behavior [18] [19] [20].

- Economics and Experimental Economics: Behaviors concerning risk, social preferences, and valuation (e.g., the endowment effect) differ significantly between the lab and the field [15] [17].

- Machine Learning and Engineering: Models for predictive maintenance (e.g., bearing fault detection) trained on clean lab data often experience a severe performance drop when deployed in noisy real-world workshops [16].

- Healthcare and Drug Development: The "efficacy-effectiveness gap" describes how a drug's performance in randomized controlled trials (efficacy) often differs from its performance in routine clinical practice (effectiveness) [21].

Why is understanding this gap critical for drug development? For drug development, the gap translates directly to the "efficacy-effectiveness gap" [21]. A drug proven efficacious in the controlled, standardized conditions of a clinical trial (the "lab") may show reduced effectiveness in the real world due to patient co-morbidities, concurrent medications, and variability in healthcare systems. Recognizing and planning for this gap is essential for accurate prediction of a drug's real-world impact and value.

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Contributing Factors

When your experimental results fail to generalize from the lab to the field, investigate these common contributing factors.

Factor 1: Divergent Social and Normative Cues

The Problem: Behavior in the laboratory is influenced by the knowledge of being observed. This can trigger "pro-social" behavior or a desire to meet perceived researcher expectations (a form of the Hawthorne Effect), which is less prominent in anonymous field settings [15].

Diagnostic Checklist:

- ☐ Did participants know they were part of a scientific study?

- ☐ Were decisions made in a private or public context within the lab?

- ☐ Is the behavior being studied sensitive to social judgment (e.g., generosity, honesty, adherence)?

Solutions:

- Implement Inferred Valuation: Instead of asking participants what they would pay for a good (which taps into normative motivations), ask them what they think another person would pay in a real-world store. This can provide a better prediction of actual field behavior [15].

- Enhance Anonymity: Design experiments to maximize the privacy and anonymity of participant decisions to reduce social desirability bias.

Factor 2: The Intention-Behavior Gap

The Problem: In behavioral research, a person's stated intention to perform an action is only a moderate predictor of their actual behavior, with intentions typically explaining only 18-30% of the variance in behavior [18] [19]. This is a fundamental internal gap that affects the translation of lab-formed intentions into field-executed actions.

Diagnostic Checklist:

- ☐ Is your research relying heavily on self-reported intentions or future plans?

- ☐ Is the target behavior difficult, complex, or requires sustained effort?

- ☐ Do participants have competing goals or distractions in the field?

Solutions:

- Measure Intention Strength: Move beyond simple intender/non-intender measures. Assess the strength of intention through its stability over time, certainty, and personal importance, as stronger intentions predict behavior more reliably [18].

- Foster Self-Determined Motivation: Encourage internal motivation (e.g., "I exercise because I enjoy it") over external pressure (e.g., "I exercise because my doctor told me to"). Support the patient's sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness to enhance follow-through [19].

- Utilize Implementation Intentions: Have participants form specific "if-then" plans (e.g., "If it is 7 am on Monday, then I will go for a 30-minute walk"). This simple cognitive strategy helps bridge the gap between intention and action [20].

Factor 3: Domain Shift and Environmental Noise

The Problem: Machine learning models and diagnostic systems trained on pristine, lab-generated data fail when faced with the different data distributions and uncontrolled noise of field environments. This is a key challenge for AI in industrial maintenance and diagnostics [16].

Diagnostic Checklist:

- ☐ Was your model trained on data from a different distribution than the deployment environment?

- ☐ Does the field environment introduce new sources of variance (e.g., ambient noise, different equipment, varying operators)?

- ☐ Is the volume of real-world fault data for training models severely limited?

Solutions:

- Employ Transfer Learning (TL): Use techniques like Transfer Component Analysis (TCA) to map data from both the lab (source domain) and field (target domain) into a shared feature space where the distribution difference is minimized. This allows knowledge learned in the lab to be effectively adapted to the field [16].

- Inject Synthetic Noise: During model training, artificially introduce noise and perturbations that emulate field conditions into your clean lab data. This builds robustness and improves generalization [16].

Factor 4: Participant Experience and Familiarity

The Problem: The lab often presents individuals with novel tasks or goods for which they have little prior experience or established decision-making strategies. In the field, people are more experienced, and their behavior is guided by learned heuristics [15] [17].

Diagnostic Checklist:

- ☐ Are the tasks or traded goods in the lab unfamiliar to the participant population?

- ☐ Would an experienced professional (e.g., a trader, a seasoned patient) perform the task differently?

Solutions:

- Stratify by Experience: In your experimental design, include and stratify participants based on their real-world experience with the task or good being studied. Analyze if lab-field correlations are stronger for experienced individuals [15].

- Incorporate Context-Rich Tasks: Move beyond abstract tasks. For example, when measuring risk attitudes, use context-rich laboratory tasks (e.g., a portfolio or insurance task) that more closely mirror real financial decisions [17].

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Risk Attitude and Field Behavior

This protocol is based on methodologies used to assess the external validity of laboratory risk attitude measures [17].

Objective: To test whether risk attitudes measured in the laboratory predict real-world financial, health, and employment risk-taking.

Materials:

- Laboratory Risk Elicitation Tasks: A battery of standard tasks, such as:

- Holt & Laury (HL) Procedure: 10 choices between paired lotteries.

- Eckel & Grossman (EG) Procedure: Choice of one lottery from six.

- Gneezy & Potters (GP) Investment Task: Decision on how much to invest in a risky asset.

- Tanaka et al. (TCN) Procedure: A complex method to estimate Prospect Theory parameters.

- Willingness to Take Risks (WTR): A simple, non-incentivized survey question [17].

- Laboratory Context-Rich Tasks: Simulated financial decisions (portfolio, insurance, and mortgage tasks) with context-rich instructions.

- Field Behavior Survey: A questionnaire capturing real-life behaviors, including:

- Financial: Investment in stocks, having a private pension fund.

- Health: Smoking, heavy drinking, junk-food consumption.

- Employment: Being self-employed.

Procedure:

- Recruitment: Recruit a large, representative sample of the population.

- Lab Session: Participants complete the five laboratory risk elicitation tasks and the three context-rich financial tasks in a randomized order. All laboratory tasks are incentivized with real monetary payouts.

- Field Survey: Subsequently, participants complete the field behavior survey.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate risk aversion parameters for each of the five laboratory measures.

- Use regression models to test the power of each lab measure to predict: a) Behavior in the context-rich laboratory financial tasks. b) The naturally-occurring field behaviors from the survey.

Expected Outcome: Simpler risk measures (like WTR) may perform as well or better than complex ones in predicting lab-based financial decisions. However, most laboratory measures will show weak to no significant correlation with a broad range of real-world risk-taking behaviors, highlighting a significant lab-field gap [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Laboratory Risk Attitude Measures

| Measure | Complexity | Theory Basis | Key Finding from Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to Take Risks (WTR) [17] | Low | None (Survey-based) | Simpler measures can outperform complex ones for lab financial decisions. |

| Eckel & Grossman (EG) [17] | Low-Medium | Expected Utility / Prospect Theory | A single choice from six lotteries. |

| Gneezy & Potters (GP) [17] | Medium | Investment-based | Involves an investment decision and multiple rounds. |

| Holt & Laury (HL) [17] | High | Expected Utility | A series of 10 paired lottery choices; complex but widely used. |

| Tanaka et al. (TCN) [17] | Very High | Prospect Theory | Estimates utility curvature and probability weighting parameters. |

| Model Type | Training Data | Test Data | Key Performance Metric (Accuracy) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Lab-recorded (Source) | Lab-recorded (Source) | High (Baseline) | Fails to generalize to new environments. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Lab-recorded (Source) | Emulated Workshop (Target) | Low (Severe performance drop) | Misclassifies balanced cases; low specificity. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) | Lab-recorded (Source) | Emulated Workshop (Target) | Up to 30% higher accuracy than ML in high-noise conditions | Struggles with mild unbalance levels when data is limited. |

Visualized Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Risk Gap Study

Transfer Learning for Domain Adaptation

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and methodological "reagents" for studying the lab-field gap.

| Research Reagent | Function in Lab-Field Research |

|---|---|

| Transfer Component Analysis (TCA) | A domain adaptation algorithm that minimizes distribution differences between lab (source) and field (target) data, enabling model generalization [16]. |

| Inferred Valuation Method | A survey technique where participants predict others' field behavior, used to reduce the bias introduced by social norms in lab valuation tasks [15]. |

| Holt & Laury (HL) Procedure | A standardized, incentivized experimental protocol for eliciting risk aversion parameters in laboratory settings [17]. |

| Implementation Intention Intervention | A simple psychological strategy where participants form "if-then" plans to bridge the intention-behavior gap [20]. |

| Context-Rich Laboratory Tasks | Laboratory decision-making tasks (e.g., portfolio, insurance) that incorporate real-world context as an intermediate step toward field generalization [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Research Artifacts

What are demand characteristics and how might they affect my experiment? Demand characteristics are cues in a research setting that inadvertently signal the study's purpose to participants [22]. Participants may then subconsciously or consciously alter their behavior, either to support the experimenter's suspected goals or to undermine the study [22]. This can lead to biased results that confirm the hypothesis but do not reflect genuine behavior.

What is the Hawthorne Effect? The Hawthorne Effect describes the phenomenon where individuals modify their behavior simply because they are aware they are being observed by researchers [22] [23]. This effect was named after a series of industrial studies in the 1920s, where workers' productivity improved in response to the attention they received from the researchers, regardless of the specific environmental changes being tested [22].

Are the Hawthorne Effect and demand characteristics the same thing? Not exactly, though they are related. The Hawthorne Effect is primarily driven by the awareness of being observed [22] [23]. In contrast, demand characteristics are driven by participants' interpretations of the experiment's purpose and their subsequent motivation to act in a certain way [22] [23]. Some researchers argue that the Hawthorne Effect is a specific type of demand effect [23].

How can I design an experiment to minimize these artifacts? Key strategies include using a control group that receives the same level of attention as the experimental group, so any Hawthorne Effect impacts both equally [22]. Employing single- or double-blind procedures where the participant and/or experimenter are unaware of the experimental condition can help reduce demand characteristics [22]. Where ethically permissible, covert observation or delaying the disclosure of the study's true purpose can also be effective [22].

Does the choice between a field or lab setting influence these artifacts? Yes, the research environment plays a significant role. The table below summarizes the core differences between these settings, which have distinct implications for the influence of artifacts.

| Feature | Field Research | Controlled Laboratory Research |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Real-world, natural setting [12] [3] | Artificially constructed and controlled setting [12] [24] |

| Control over Variables | Low; many extraneous variables exist [12] [3] | High; researcher can isolate and manipulate variables precisely [12] [24] |

| Realism (Ecological Validity) | High [12] [3] | Low [3] |

| Generalizability (External Validity) | Typically higher to real-life contexts [12] | Limited; may not apply outside the lab [3] |

| Likelihood of Hawthorne Effect/Demand Characteristics | Can vary; participants may not know they are studied, but the complex environment introduces other biases [12] | Typically higher, as participants know they are in a study and the setting can create strong demand characteristics [3] |

| Primary Research Goal | To observe and describe behavior in a natural context [12] | To establish cause-and-effect relationships with high internal validity [12] [24] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Mitigating Artifacts

Guide 1: My results are suspiciously perfect – could participant bias be the cause?

Symptoms: Your data aligns perfectly with your hypothesis. Participants perform as expected, with little to no variation. You may suspect that participants have guessed the purpose of your study.

Diagnosis: This pattern strongly suggests the influence of demand characteristics. Participants are likely acting based on their perception of what the experiment is about, rather than responding naturally.

Action Plan:

- Review Your Script: Examine the instructions given to participants. Remove any leading language or emphasis that might hint at the expected outcome.

- Implement Blinding: Use a single-blind design where participants do not know their experimental group (e.g., treatment vs. placebo), or a double-blind design where both participants and experimenters are unaware [22]. This is a gold standard in drug development.

- Use Filler Tasks: Incorporate tasks or questions that are irrelevant to the main hypothesis to help disguise the true purpose of the study.

- Post-Experiment Inquiry: After data collection, ask participants what they thought the study was about. This can help you determine if their suspicions aligned with the hypothesis.

Guide 2: I observed a performance boost just from monitoring participants – what happened?

Symptoms: Productivity or performance metrics improve significantly when you introduce a new observational method (e.g., a new sensor, more frequent check-ins, or simply because participants know they are in a study), but this effect diminishes over time.

Diagnosis: This is a classic sign of the Hawthorne Effect or the Novelty Effect [22]. The change is driven by the increased attention from researchers, not by the specific intervention being tested.

Action Plan:

- Use a Control Group: Include a group that receives an equal amount of attention and interaction from the research team but does not receive the experimental intervention. This allows you to isolate the effect of the attention itself [22].

- Discard Initial Data: When possible, plan for a habituation or run-in period. Discard data from the initial phase of the study while participants are acclimating to the novelty of being observed [22].

- Normalize Observation: Make the observation as unobtrusive and routine as possible. Automated, passive data collection can sometimes help reduce this effect.

Guide 3: My experiment failed – how do I systematically troubleshoot it?

Symptoms: An experiment produces unexpected results, a complete failure, or high variability, and the cause is unknown. The issue could be technical, biological, or related to participant behavior.

Diagnosis: Effective troubleshooting requires a structured, step-by-step approach to isolate the variable causing the problem. This methodology is crucial in both lab and field settings [25] [26].

Action Plan: Follow this logical troubleshooting workflow, changing only one variable at a time:

- Repeat the Experiment: Before deep investigation, simply repeat the procedure to rule out simple human error, like a pipetting mistake or incorrect calculation [26].

- Verify the Result's Meaning: Critically assess whether the "failed" experiment might actually be a valid, unexpected result. Return to the scientific literature to see if there are other plausible explanations for your data [26].

- Check Controls and Equipment: Ensure all positive and negative controls are performing as expected. Check that reagents have been stored correctly and haven't expired. Verify that all equipment is functioning and properly calibrated [26] [27].

- Change One Variable at a Time: Generate a list of possible variables that could be causing the problem (e.g., concentration, temperature, timing, participant group). Systematically test each one, ensuring only a single change is made between experiments to clearly identify the cause [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table outlines key methodological "reagents" for designing robust studies that account for artifacts.

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research Design |

|---|---|

| Control Group | Serves as a baseline; any difference from this group is attributed to the experimental intervention. When matched for researcher attention, it helps control for the Hawthorne Effect [22]. |

| Blinding (Single/Double) | A procedural "reagent" that prevents participants (single-blind) and/or experimenters (double-blind) from knowing group assignments, thereby reducing demand characteristics and observer bias [22]. |

| Deception / Cover Story | Used to mask the true hypothesis from participants, reducing the likelihood that they will alter their behavior based on perceived demands [22]. Must be used ethically and with debriefing. |

| Habituation Period | An initial phase where participants become accustomed to the research setting and procedures. Data from this period is often discarded, allowing the novelty effect to wear off [22]. |

| Behavioral Measures | Indirect or objective measures (e.g., reaction time, physiological data) that are less susceptible to conscious control and demand characteristics than self-report measures like surveys. |

Observational Research Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the psychological pathway through which observation can lead to behavioral change, and the methodological controls researchers can implement.

Methodological Bridges: Integrating Field and Lab Approaches for Stronger Evidence

Lab-in-the-field experiments represent a sophisticated methodological bridge between highly controlled laboratory studies and purely observational field research. By conducting controlled experiments with non-standard populations in their natural environments, researchers can investigate complex human behaviors with both empirical rigor and ecological validity [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for research on field versus laboratory behavior correlation, as it allows for direct observation of how theoretical models manifest in real-world contexts with diverse participant populations [12] [4].

Key Concepts and Definitions

Understanding Experimental Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of different experimental methodologies, highlighting how lab-in-the-field experiments occupy a unique middle ground.

| Experimental Type | Subject Pool | Environment | Key Characteristics | Primary Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Laboratory Research [12] | Standard (e.g., students) | Artificial, specifically designed setting | High control, manipulation of variables, basic, repeatable | High internal validity, reproducibility, efficiency [12] |

| Lab-in-the-Field Experiment [4] | Non-standard (e.g., specific target populations) | Natural or semi-natural setting | Controlled tasks with field context, "extra-lab" | Ecological validity, diverse subjects, context insights [4] |

| Natural Field Experiment [4] | Non-standard, unaware of study | Purely natural setting | Participants unaware they are in an experiment | High external validity, minimizes observer bias [4] |

| Field Research [12] | Non-standard | Real-world, natural setting | Observational, descriptive, correlational | Generalizability to real-life contexts [12] |

Validity Considerations

A central challenge in behavior research is balancing internal and external validity [12].

- Internal Validity: The extent to which observed effects can be confidently attributed to the manipulated independent variable, rather than confounding factors. This is typically maximized in controlled lab settings [12].

- External Validity: The degree to which research findings can be generalized to other populations, settings, and times. This is a key strength of field research [12].

Lab-in-the-field experiments explicitly aim to find a workable balance between these two types of validity, preserving enough control for causal inference while maintaining sufficient realism for generalizability [12] [4].

Common Research Challenges & Troubleshooting

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when implementing lab-in-the-field experiments. The following table outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions.

| Research Challenge | Potential Impact on Data | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Ecological Validity [12] | Artificial behavior that does not reflect real-world actions | Move experimentation to the field setting or incorporate field context into tasks [4] |

| Limited Subject Pool Diversity [4] | Findings that don't generalize beyond Western, educated populations | Recruit non-standard subjects from specific target populations (e.g., public servants, farmers) [4] |

| Uncontrolled Extraneous Variables [12] | Reduced internal validity; ambiguity in causal inference | Implement strict protocols, use control groups, and carefully document environmental conditions [12] |

| Participant Literacy or Comprehension [28] | Measurement error, noise in data | Simplify instructions, use visual aids, conduct pilots to ensure tasks are understood [28] |

| Ethical Constraints in Natural Settings [12] | Limitations on study design, potential for harm | Ensure informed consent, protect privacy, and engage with local communities [28] [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary research question that lab-in-the-field experiments are best suited to answer?

This methodology is particularly powerful for questions where the subject pool's specific characteristics, experiences, or context are central to the behavior being studied [28] [4]. For example, it is ideal for examining whether behavioral patterns observed in student subjects in a lab hold true for specialists like public servants, nurses, or CEOs in a more relevant context [4].

2. How can I improve the reliability of data collected in a less-controlled field environment?

Key strategies include [28]:

- Extensive Piloting: Conduct pilots in both the lab and the field to refine tasks and procedures.

- Trained Research Assistments: Use facilitators who understand both the experimental protocol and the local context.

- Community Involvement: Engage with the participant community to build trust and ensure the research is conducted appropriately.

- Clear Payoffs: Ensure financial incentives or other payoffs are salient, understandable, and meaningful to the participants.

3. My results from a lab-in-the-field experiment differ from previous laboratory studies. What does this mean?

This is a common and valuable outcome. Such discrepancies can reveal the critical influence of context or population characteristics on the behavior in question [4]. For instance, a study found that public servants were less corrupt than students in an experiment, suggesting that experience, not just selection, shapes behavior [4]. This divergence does not invalidate either study but enriches the understanding of the phenomenon.

4. What are the key ethical considerations when running experiments outside the lab?

Beyond standard ethical review, special attention should be paid to [28] [12]:

- Informed Consent: Ensure participants fully understand the study, even in natural settings where they might not typically expect research.

- Privacy and Confidentiality: Protect the data and identity of participants, especially in close-knit communities.

- Debriefing: Clearly explain the purpose of the study after its completion, which can also help maintain goodwill for future research.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Standard Workflow for Lab-in-the-Field Experiments

The diagram below outlines a generalized protocol for designing and implementing a robust lab-in-the-field study.

Classification of Economic Experiments

The following diagram illustrates how lab-in-the-field experiments are classified within the broader spectrum of economic research methods, based on criteria such as subject pool, environment, and task nature [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

While lab-in-the-field experiments in social sciences and economics do not use chemical reagents, they rely on a different set of essential "research reagents" – the standardized tools and protocols used to elicit and measure behavior.

| Tool Category | Example "Reagents" | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Elicitation Tasks [4] | Risk preference games (e.g., lottery choices), Public goods games, Dictator games | Measure underlying individual preferences (risk aversion, cooperation, altruism) in a quantifiable way. |

| Context Framing [4] | Field-specific commodities (e.g., real public good), Contextual backstories | Incorporate field context into the experimental task to make it more relevant and salient to participants. |

| Data Collection Instruments [28] | Pre-/post-experiment surveys, Cognitive tests, Physiological measures (e.g., stress) | Collect demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral data to complement primary experimental data. |

| Participant Recruitment Materials [28] | Community engagement plans, Informed consent forms, Recruitment scripts | Ensure ethical and effective recruitment of non-standard subject pools, building trust and understanding. |

| Incentive Systems [28] | Monetary payoffs, In-kind gifts, Show-up fees | Motivate participation and ensure decisions in the experiment have real consequences for participants. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary goal of the Inferred Valuation Method? The primary goal is to bridge the gap between controlled laboratory studies and real-world field behavior. It uses data collected in a lab environment to build statistical models that predict how individuals or systems will behave in more complex, naturalistic field settings. This is crucial for validating lab findings and ensuring they have practical applicability [3].

Q2: My lab-to-field predictions are inconsistent. What could be causing this? Inconsistencies often stem from demand characteristics in the lab, where participants alter their behavior based on perceived expectations. Another common cause is the artificial environment of the lab, which fails to capture all the variables present in a real-world context. Review your experimental design to see if it adequately simulates key field conditions [3].

Q3: How can I improve the generalizability of my lab findings? To enhance generalizability, incorporate elements of naturalistic observation into your lab protocols where possible. Furthermore, use statistical techniques to control for confounding variables that are present in the field but not in the lab. Conducting longitudinal studies can also help track how behaviors evolve over time, making predictions more robust [3].

Q4: What are the key limitations when trying to replicate field conditions in a lab? The main limitations are the lack of control over external variables and the difficulty in replication itself. The lab's controlled environment, while a strength for isolating variables, is also its greatest weakness because it cannot perfectly recreate the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the real world [3].

Q5: What ethical considerations are unique to this kind of research? Research that correlates lab and field data must carefully consider informed consent, especially regarding how data will be used across different environments. Ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participant information is paramount, as is being mindful of any potential harm or distress that participants might experience when being observed in a field setting [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Correlation Between Lab Results and Field Observations

Description The data and behaviors observed in the controlled laboratory setting do not significantly correlate with the behaviors recorded in the natural field environment, threatening the validity of your predictions.

Solution Steps

- Audit Lab Protocols: Scrutinize your lab procedures for demand characteristics—cues that accidentally signal to participants what the expected outcome is. Modify the protocol to make these cues less obvious [3].

- Increase Environmental Fidelity: Enhance the physical and social realism of your lab environment to better mirror the field context you wish to predict. This could involve simulating distractions, using more realistic stimuli, or incorporating social interactions [3].

- Validate Measures: Ensure that the metrics you are collecting in the lab (e.g., response times, self-reports) are actually measuring the same underlying construct as your field observations. Conduct a pilot study to validate these measures.

Prevention Tips

- At the research design stage, invest time in conducting thorough field observations to identify the key variables that must be replicated in the lab.

- Use blinded procedures during data analysis to prevent experimenter bias from influencing the correlation results [3].

Problem: High Variance in Inferred Valuation Metrics

Description The inferred valuation scores (e.g., calculated willingness-to-pay, behavioral intention scores) show high variability between subjects, making it difficult to identify a clear predictive pattern.

Solution Steps

- Stratify Your Sample: Analyze your data for subgroups based on demographics or psychographics. High overall variance can often mask clear patterns within specific participant segments.

- Control for Confounding Variables: Identify and statistically control for variables known to affect the outcome but not central to your hypothesis. This can be done during the experimental design (e.g., blocking) or during data analysis (e.g., analysis of covariance).

- Increase Sample Size: A larger sample size can help provide a more stable and reliable estimate of the population parameters, reducing the impact of random variability.

Prevention Tips

- Implement standardized procedures for every participant to minimize noise introduced by variations in the experimental process [3].

- Use pre-screening questionnaires to create a more homogeneous sample if appropriate for your research question.

Problem: Model Fails to Predict Non-Linear Field Behavior

Description Your statistical model, built on linear relationships from lab data, fails to accurately predict complex, non-linear behaviors observed in the field.

Solution Steps

- Explore Non-Linear Models: Investigate machine learning techniques or statistical models capable of capturing non-linear relationships, such as decision trees, polynomial regression, or Gaussian processes.

- Incorporate Interaction Terms: Re-analyze your lab data by including interaction terms between key independent variables. This can reveal how the effect of one variable depends on the level of another.

- Collect richer lab data: Design lab experiments that are capable of eliciting and capturing a wider range of behaviors, including extreme or non-linear responses.

Prevention Tips

- Based on initial field work, formulate hypotheses about potential non-linear effects and deliberately design lab experiments to test for them.

- Before finalizing your model, use cross-validation techniques on your lab data to check for patterns in the prediction errors that might suggest non-linearity.

Experimental Workflows & Data Presentation

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Inferred Valuation Method

The following workflow outlines the key stages for a study using the Inferred Valuation Method to predict field behavior from lab data, such as in a study on consumer willingness-to-pay.

The following table summarizes hypothetical data from a validation study comparing different predictive models.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Predictive Models for Field Behavior

| Model Type | Lab Data R² | Field Prediction R² | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 0.85 | 0.45 | 12.5 | Simple, interpretable |

| Random Forest | 0.88 | 0.62 | 8.7 | Handles non-linear relationships |

| Neural Network | 0.90 | 0.68 | 7.9 | High predictive accuracy |

| Bayesian Model | 0.83 | 0.58 | 9.2 | Incorporates prior knowledge |

Decision Framework for Research Environment Selection

Choosing the right environment is critical. The following diagram outlines the key decision points.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Behavioral Correlation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Behavioral Task Software (e.g., PsychoPy, Inquisit) | Presents standardized stimuli and records participant responses (reaction time, accuracy) in the lab setting. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) Platform | Collects real-time self-report data from participants in their natural environment via smartphones, reducing recall bias. |

| Data Synchronization Tool | Aligns timestamps and merges datasets collected from disparate sources (lab software, mobile apps, biometric sensors). |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, Python) | Performs the complex statistical modeling (e.g., multilevel modeling, machine learning) required to link lab and field data. |

| Biometric Sensors (e.g., EDA, HRV) | Provides objective, physiological measures of arousal or stress that complement subjective self-reports in both lab and field. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Understanding Framed Field Experiments

Q: What is a Framed Field Experiment, and how does it differ from a standard lab experiment? A: A Framed Field Experiment is a research method that utilizes controlled procedures from a laboratory setting but applies them within a real-world (field) context and with a non-standard subject pool [12]. Unlike a purely controlled laboratory study, which is a tightly controlled investigation in an artificial environment, a framed field experiment introduces the control of a lab into a natural setting. This allows researchers to observe behaviors that are more generalizable to real-life situations while maintaining a degree of experimental control [12] [29].

Q: When should I choose a Framed Field Experiment over a traditional lab study? A: Opt for a framed field experiment when your research question requires higher external validity (generalizability to real contexts) than a lab can provide, but you still need to manipulate an independent variable to establish cause-and-effect, which is often difficult in a purely observational field study [12]. It is a compromise that permits sufficient control for internal validity while maintaining realism for generalizability [12].

Design and Implementation Troubleshooting

Q: I am concerned that my experimental controls are being "contaminated" by the field environment. What should I do? A: This is a common challenge. The key is to meticulously document all contextual variables in your field setting [12]. Create a detailed protocol that standardizes the procedure as much as possible, and use a control group within the same field context to account for extraneous influences. The goal is not to eliminate all external variables (as in a lab) but to understand and control for them statistically [12].

Q: My subjects are behaving differently because they know they are being studied. How can I mitigate this? A: While participants in field settings may be less aware of the experiment than in a lab, this can still occur [12]. To mitigate this, frame the experiment's context in a way that feels natural and engaging to the participants. Ensure that informed consent procedures are ethically sound but do not unnecessarily reveal the specific hypotheses being tested, which could lead to response bias.

Q: I am having trouble with the logistical planning of a field experiment. Where should I start? A: Start by piloting your experiment with a small group. A pilot will help you identify logistical hurdles, refine your data collection instruments, and ensure your experimental procedures work as intended in the real-world context. The Field Experiments Website provides numerous examples of well-designed framed field experiments that can serve as a model for your own structure and planning [29].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Q: How do I establish causality in a Framed Field Experiment when I cannot control every variable? A: Causality is primarily established through the random assignment of subjects to treatment and control groups. By randomly assigning participants, you help ensure that any observed effects on the dependent variable are likely due to your manipulation of the independent variable, not other confounding factors [12]. Your analysis should then compare the outcomes between these groups.

Q: My quantitative results are difficult to interpret in isolation. What is the best approach? A: A mixed-methods approach is often highly fruitful. Supplement your quantitative data with qualitative data, such as post-experiment interviews or surveys, to provide richer context and help explain the "why" behind the numbers. This can be crucial for interpreting unexpected results or understanding participant motivation [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Designing a Basic Framed Field Experiment

This protocol outlines the core steps for creating a valid Framed Field Experiment.

- Define Research Question & Hypothesis: Clearly state the causal relationship you intend to test.

- Identify Independent & Dependent Variables: The independent variable is the factor you manipulate. The dependent variable is the outcome you measure [12].

- Select Field Context & Participant Pool: Choose a natural environment and a subject pool that is relevant to your research question (e.g., teachers in schools, shoppers in a store) [29].

- Develop Experimental Procedure & "Frame": Design a standardized set of instructions and tasks for participants. The "frame" embeds the laboratory-style task within a context that is meaningful to the participants in their natural environment.

- Random Assignment: Randomly assign participants to either the treatment group (which experiences the manipulated independent variable) or the control group (which does not).

- Execute Experiment & Monitor Fidelity: Conduct the experiment in the field setting, ensuring procedures are followed consistently to maintain internal validity [12].

- Collect & Analyze Data: Gather data on the dependent variable and use statistical methods to compare outcomes between the treatment and control groups.

- Interpret Results: Draw conclusions based on your analysis, considering the limitations and specific context of your field setting.

Protocol 2: Testing the Impact of Information on Decision-Making

This methodology is adapted from studies on misinformation and critical thinking cited on The Field Experiments Website [29].

- Objective: To understand the causal effect of providing specific information on subsequent choices and beliefs in a real-world context.

- Independent Variable: Exposure to a specific piece of information (e.g., a factual article, a warning label, a peer's review). This is manipulated by randomly assigning the informational treatment.

- Dependent Variable: A measurable decision or belief statement made by participants after exposure, often captured through a survey or an actual choice (e.g., product selection, agreement with a statement).

- Procedure:

- Recruit participants from a natural subject pool (e.g., online panel, community group).

- Randomly assign them to a control group (receives no additional information or placebo information) or one or more treatment groups.

- Treatment groups are presented with the specific information framed within a realistic scenario.

- All participants then complete the same task or survey designed to measure the dependent variable.

- Data is aggregated and analyzed to detect statistically significant differences between the groups.

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Research Methodologies

| Characteristic | Controlled Laboratory Research | Framed Field Experiment | Naturalistic Field Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Artificial environment designed for research [12] | Real-world environment with controlled procedures [29] | Purely natural setting [12] |

| Control Over Variables | High; extraneous variables are minimized [12] | Moderate; key variables are manipulated, others are documented [12] | Low; observes existing conditions [12] |

| Participant Awareness | Usually aware of being studied [12] | Varies, but often embedded in a natural context | May or may not be aware [12] |

| Internal Validity | High [12] | Moderate to High | Low |

| External Validity | Low [12] | Moderate to High [12] | High [12] |

| Primary Use | Establishing cause-and-effect under pure conditions [12] | Testing theories and establishing causality in applied settings [29] | Discovering correlations and generating hypotheses [12] |

Table 2: Example Data from Framed Field Experiments

| Study Focus / Title (from The Field Experiments Website) | Key Independent Variable(s) | Key Dependent Variable(s) | Sample Context / Participant Pool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Why Don't Struggling Students Do Their Homework? [29] | Motivation interventions, study productivity tools | Homework completion rates, academic performance | Students in an educational institution |

| The Impact of Fake Reviews on Demand and Welfare [29] | Presence and type of fake reviews | Consumer demand, product choice, welfare measures | Online shoppers |

| Judging Nudging: Understanding the Welfare Effects of Nudges Versus Taxes [29] | Policy type (nudge vs. tax) | Consumer behavior change, economic welfare | Consumers in a market simulation |

| The Effect of Performance-Based Incentives on Educational Achievement [29] | Monetary incentives for students or teachers | Test scores, graduation rates | Students and teachers in schools |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Framed Field Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Randomization Software | To ensure unbiased assignment of participants to treatment and control groups, which is fundamental for establishing causality. |

| Standardized Protocol Scripts | To ensure consistent delivery of instructions and procedures across all participants, protecting internal validity. |

| Digital Data Collection Platform | To efficiently and accurately collect dependent variable data from participants in the field (e.g., via tablets, online surveys). |

| Contextual Data Capture Tools | To record key environmental variables from the field setting (e.g., time of day, ambient conditions) for use in later analysis. |

| Participant Incentive Structure | To ethically compensate participants for their time and effort, framed in a way that aligns with the natural context of the experiment. |

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

Diagram 1: Framed Field Experiment Workflow

Diagram 2: Validity Trade-offs in Methodologies

Sequential research designs are mixed methods approaches where data collection and analysis occur in distinct phases. The explanatory sequential design is a prominent type, where researchers first collect and analyze quantitative data, then use qualitative methods to explain or elaborate on the initial findings [30]. This methodology is particularly valuable for connecting field observations with laboratory experimentation, as it provides a structured framework for generating hypotheses from real-world data and then testing them under controlled conditions.

In the context of field versus laboratory behavior correlation research, this design enables researchers to identify patterns or anomalies in field data (quantitative phase) and then conduct in-depth laboratory investigations (qualitative phase) to understand the underlying mechanisms. The integration of findings from both phases produces a more comprehensive understanding of behavioral correlations than either approach could achieve independently [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Unexpected Experimental Results

Q: My laboratory experiment produced results that contradict my field observations. How should I troubleshoot this discrepancy?

A: Discrepancies between field and lab findings often reveal important insights. Follow this systematic troubleshooting approach:

- Repeat the experiment: Unless cost or time prohibitive, first repeat your experiment to rule out simple human error or technical mistakes [26].

- Verify your assumptions: Re-examine whether your initial hypothesis was testable and whether your experimental design appropriately modeled the field conditions [31].

- Review methodological factors:

- Check equipment calibration and functionality

- Confirm reagent freshness, purity, and storage conditions [26]

- Verify sample representativeness and consistency

- Validate your control groups

- Compare with existing literature: Consult previous studies, literature reviews, and databases to see if others have reported similar findings [31].

- Test alternative hypotheses: Design experiments to explore other possible explanations for your results [31].

Table: Troubleshooting Unexpected Results

| Issue | Potential Causes | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Contradictory findings between field and lab | Field variables not adequately replicated in lab | Systematically identify and incorporate key field variables into lab design |

| Inconsistent experimental outcomes | Technical errors; reagent problems; equipment issues | Repeat experiment; check reagents and equipment; include appropriate controls [26] |

| Unexplained outliers in data | Natural variation; measurement error; novel phenomenon | Determine if outliers represent errors or meaningful discoveries [30] |

Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Q: How can I effectively integrate quantitative field data with qualitative laboratory findings?

A: Successful integration requires careful planning at both research phases:

- Design connection points: Plan how quantitative results will inform qualitative data collection before beginning your study [30].

- Use quantitative findings to guide qualitative exploration: Look for significant results, unexpected patterns, or outliers in your field data that warrant deeper investigation in the lab [30].

- Implement iterative analysis: Analyze quantitative data first, then develop qualitative questions based on those findings [30].

- Connect methodologies explicitly: Document how your laboratory experiments directly address specific questions raised by field observations.

Sequential Research Integration Workflow

Managing Time-Intensive Sequential Protocols

Q: The sequential nature of this research approach seems time-intensive. How can I manage these demands efficiently?

A: The explanatory sequential design does require significant time investment, but these strategies can optimize your workflow [30]:

- Plan both phases concurrently: While data collection is sequential, you can plan the qualitative phase while conducting the quantitative phase.

- Secure comprehensive IRB approval: Obtain approval for both phases simultaneously by outlining a tentative framework for the second phase [30].

- Pre-identify participants: Inform initial participants about the possibility of follow-up contact to streamline the second phase recruitment [30].

- Use preliminary quantitative analysis: Begin analyzing quantitative data as it's collected to identify early targets for qualitative investigation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What philosophical assumptions underlie sequential research designs?

A: Sequential research embodies philosophical pluralism, allowing researchers to adopt different paradigms for distinct study phases. The quantitative phase often aligns with postpositivism, emphasizing objective measurement and hypothesis testing, while the qualitative phase typically follows constructivism, prioritizing subjective understanding and contextual insight. This flexibility aligns with pragmatism, which emphasizes using whatever approaches best address the research questions [30].

Q: When is explanatory sequential design most appropriate for field-lab correlation studies?

A: This design is particularly valuable when [30]:

- You need qualitative data to explain unexpected quantitative results

- Your field observations reveal patterns requiring laboratory investigation

- You want to use quantitative findings to guide purposeful sampling for qualitative experiments

- You're working individually or with a small team (as data collection is sequential, not simultaneous)

Q: How do I select which quantitative findings to explore in the laboratory phase?

A: Prioritize these types of quantitative results for further qualitative investigation [30]:

- Statistically significant or highly significant results

- Unexpected patterns or anomalies

- Results that contradict existing theories or field observations

- Outlier data points that deviate substantially from the norm

- Findings with potentially important practical implications

Q: What are the most common challenges in sequential research, and how can I address them?

A: The primary challenges include [30]:

- Time demands: The two-phase approach can be lengthy

- IRB approvals: Obtaining approval for a second phase dependent on first-phase results

- Sample identification: Selecting appropriate participants for the qualitative phase

- Methodological alignment: Ensuring laboratory methods adequately address field-generated questions

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Bind to specific proteins of interest | Immunohistochemistry; protein detection in tissue samples [26] |

| Secondary Antibodies | Fluorescent proteins bind to primary antibodies for visualization | Target detection and imaging [26] |

| Buffer Solutions | Rinse off excess antibodies; maintain pH stability | Washing steps in experimental protocols [26] |

| Fixation Agents | Preserve tissue structure and integrity | Sample preparation for histological analysis [26] |

| Blocking Agents | Minimize background signals and non-specific binding | Improving signal-to-noise ratio in detection assays [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Integrated Field-Lab Research Protocol

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for connecting field observations with laboratory experimentation:

Phase 1: Quantitative Field Data Collection

- Design quantitative research questions aligned with study objectives

- Identify and recruit a representative sample population

- Collect quantitative data through surveys, sensors, or behavioral measures

- Analyze data to identify patterns, relationships, or anomalies [30]

Phase 2: Qualitative Laboratory Investigation

- Determine which quantitative findings require deeper exploration

- Develop laboratory experiments or interviews based on quantitative results

- Select participants who can best explain the quantitative findings

- Collect and analyze qualitative data using appropriate methods [30]

Phase 3: Integration and Interpretation

- Compare and combine insights from both datasets

- Identify connections between quantitative and qualitative findings