Dynamic Programming vs. Reinforcement Learning in Drug Development: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Dynamic Programming (DP) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Dynamic Programming vs. Reinforcement Learning in Drug Development: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Dynamic Programming (DP) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both methodologies, detailing their specific applications in areas like long-term preventive therapy optimization and antimicrobial drug cycling. The content addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, including data requirements, reward function design, and model stability. Finally, it presents a validated, comparative analysis of performance across different data scenarios, offering evidence-based guidance for selecting the optimal approach in biomedical research and clinical decision-support systems.

Core Principles: Demystifying Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning

The fields of dynamic programming (DP), approximate dynamic programming (ADP), and reinforcement learning (RL) are unified by a common mathematical framework: Bellman operators and their projected variants [1]. While these research traditions developed largely in parallel across different scientific communities, they ultimately implement variations of the same operator-projection paradigm [1]. This foundational understanding reveals that reinforcement learning algorithms represent sample-based implementations of classical dynamic programming techniques, bridging the gap between theoretical optimality and practical, data-driven learning [1].

Within this unified perspective, a fundamental distinction emerges between model-based and model-free reinforcement learning approaches. Model-based RL maintains a direct connection to dynamic programming principles by learning explicit models of environment dynamics, while model-free RL embraces a pure trial-and-error methodology, learning optimal policies directly from environmental interactions without modeling underlying dynamics [2]. This comparison guide examines these competing paradigms through both theoretical and practical lenses, with particular emphasis on applications in drug discovery and development where both approaches have demonstrated significant utility.

Theoretical Foundations: Model-Based vs. Model-Free RL

Core Definitions and Mathematical Framework

Any reinforcement learning problem can be formally described as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defined by the tuple (S, A, R, T, γ) where S represents the state space, A the action space, R the reward function, T(s'|s,a) the transition dynamics, and γ the discount factor [2]. The fundamental distinction between model-based and model-free approaches lies in how they handle the transition dynamics (T) and reward function (R).

In model-free RL, the agent treats the environment as a black box, learning policies or value functions directly from observed state transitions and rewards without attempting to learn an explicit model of the environment's dynamics [2] [3]. The agent's goal is simply to learn an optimal policy π(s) that maps states to actions through repeated interaction with the environment [2].

In contrast, model-based RL involves learning approximations of both the transition function T and reward function R, then using these learned models to simulate experiences and plan future actions [2] [3]. This approach leverages the learned environment dynamics to increase training efficiency and policy performance [2].

Algorithmic Characteristics and Performance Trade-offs

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and trade-offs between model-based and model-free reinforcement learning approaches:

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Model-Based vs. Model-Free Reinforcement Learning

| Feature | Model-Free RL | Model-Based RL |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Approach | Direct learning from environment interactions | Indirect learning through model building |

| Sample Efficiency | Requires more real-world interactions | More sample-efficient; can simulate experiences |

| Asymptotic Performance | Higher eventual performance with sufficient data | May plateau at lower performance due to model bias |

| Implementation Complexity | Relatively simpler to implement | More complex due to model learning and maintenance |

| Adaptability to Changes | Slower to adapt to environmental changes | Faster adaptation with accurate model updates |

| Computational Requirements | Generally less computationally intensive | More demanding due to model learning and planning |

| Key Algorithms | Q-Learning, SARSA, DQN, PPO, REINFORCE | Dyna-Q, Model-Based Value Iteration, MCTS |

Model-free methods tend to achieve higher asymptotic performance given sufficient environment interactions, as they make no potentially inaccurate assumptions about environment dynamics [2]. However, model-based approaches typically demonstrate significantly better sample efficiency, often achieving comparable performance with far fewer environmental interactions [2] [3]. This efficiency stems from the ability to generate artificial training data through model-based simulations and to propagate gradients through predicted trajectories [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model-Based RL Workflow for Drug Design

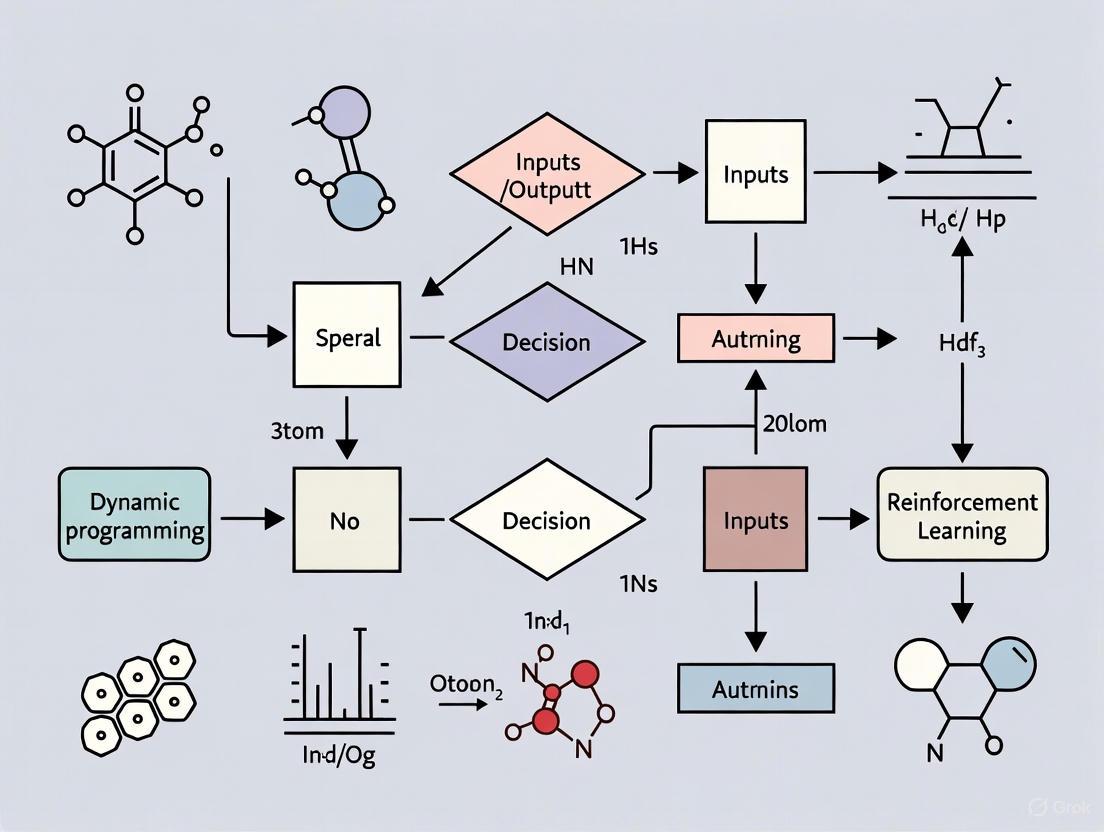

The model-based approach has demonstrated particular utility in computational drug design, where it enables efficient exploration of chemical space. The following diagram illustrates a representative model-based RL workflow for de novo drug design:

Diagram 1: Model-Based RL in Drug Design (76 characters)

This model-based framework integrates pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) modeling with virtual patient generation to enable in silico clinical trials [4]. The approach begins with an initial compound library used to develop PK models (describing what the body does to the drug) and PD models (describing what the drug does to the body) [4]. These models then inform the generation of virtual patient cohorts that capture population heterogeneity, enabling simulation of clinical trials in silico [4]. The results feed back into compound optimization, creating an iterative refinement cycle that significantly reduces the need for physical testing [4].

A specific implementation of this paradigm is the ReLeaSE (Reinforcement Learning for Structural Evolution) method, which integrates two deep neural networks: a generative model that produces novel chemically feasible molecules, and a predictive model that forecasts their properties [5]. In this system, the generative model acts as an agent proposing new compounds, while the predictive model serves as a critic, assigning rewards based on predicted properties [5]. The models are first trained separately using supervised learning, then jointly optimized using reinforcement learning to bias compound generation toward desired characteristics [5].

Model-Free RL Workflow for Bioactive Compound Design

Model-free reinforcement learning offers a distinct approach that has proven effective for designing bioactive compounds with specific target interactions. The following diagram illustrates a representative model-free RL workflow:

Diagram 2: Model-Free RL for Compound Design (76 characters)

This model-free approach addresses the significant challenge of sparse rewards in drug discovery, where only a tiny fraction of generated compounds exhibit the desired bioactivity [6]. Technical innovations such as experience replay (storing and retraining on successful compounds), transfer learning (pre-training on general compound libraries before specialization), and reward shaping (providing intermediate rewards) have proven essential for balancing exploration and exploitation [6].

In practice, the generative model is typically pre-trained on a diverse dataset of drug-like molecules (such as ChEMBL) to learn valid chemical representations [6]. The model then generates compounds represented as SMILES strings, which are evaluated by a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model predicting target bioactivity [6]. The reward signal derived from this prediction guides policy updates through algorithms like REINFORCE, progressively shifting the generator toward compounds with higher predicted activity [6].

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes experimental performance data for model-based and model-free reinforcement learning across various applications:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of RL Paradigms

| Application Domain | Model-Based RL Performance | Model-Free RL Performance | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo Drug Design | 27% reduction in patients treated with suboptimal doses [7] | Rediscovery of known EGFR scaffolds with experimental validation [6] | Efficiency, Hit Rate |

| Sample Efficiency | Significantly reduced sample complexity [2] | Requires extensive environmental interactions [2] [8] | Training Samples Needed |

| Clinical Trial Optimization | More precise dose selection (8.3% vs 30% error) [7] | Not typically applied to trial design | Dose Accuracy |

| Computational Requirements | Higher due to model learning and planning [2] [3] | Less computationally intensive per interaction [3] | Training Time, Resources |

| Adaptability to Changes | Faster adaptation with model updates [2] [3] | Slower adaptation requiring new experiences [3] | Response to Environment Shift |

In anticancer drug development, a two-stage model-based design demonstrated significant advantages over conventional approaches, reducing the number of patients treated with subtherapeutic doses by 27% while providing more precise dose selection for phase II evaluation (8.3% root mean squared error versus 30% with conventional methods) [7]. This approach leveraged pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling to optimize starting doses for subsequent studies, demonstrating both safety and efficiency improvements [7].

Meanwhile, model-free approaches have shown remarkable success in designing bioactive compounds. In a proof-of-concept study targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, model-free RL successfully generated novel compounds containing privileged EGFR scaffolds that were subsequently validated experimentally [6]. This success was enabled by technical solutions addressing the sparse reward problem, as the pure policy gradient algorithm alone failed to discover molecules with high predicted activity [6].

Domain-Specific Application Scenarios

The comparative advantages of each approach become particularly evident in specific application scenarios:

For autonomous navigation in complex environments such as forest drone delivery, model-based RL excels due to its ability to simulate numerous potential paths and adapt to dynamic obstacles without physical risk [3]. The predictive capability enables efficient planning and real-time adjustment to terrain changes while optimizing resource usage and ensuring safety [3].

Conversely, for learning novel video games with complex, unpredictable environments, model-free RL proves more suitable as the environment dynamics are often too complex to accurately model [3]. The direct trial-and-error learning approach allows the agent to discover effective strategies through interaction without requiring an explicit world model [3].

In drug discovery applications, model-based approaches particularly shine when simulation environments are available or when physical trials are expensive or ethically constrained [7] [4]. Model-free methods demonstrate strengths when exploring complex chemical spaces where relationships between structure and activity are difficult to model explicitly but can be learned through iterative experimentation [5] [6].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details key computational tools and methodologies essential for implementing both model-based and model-free reinforcement learning in drug discovery and development:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Reinforcement Learning in Drug Development

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Stack-RNN [5], Variational Autoencoders [2] | Generate novel molecular structures represented as SMILES strings or molecular graphs |

| Predictive Models | QSAR Models [6], Random Forest Ensembles [6] | Predict biological activity and physicochemical properties of generated compounds |

| Simulation Environments | PK/PD Model Simulations [4], Virtual Patient Cohorts [4] | Simulate drug pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and population variability |

| RL Frameworks | TensorFlow Agents, Ray RLlib, OpenAI Gym [9] | Provide infrastructure for implementing and training reinforcement learning agents |

| Planning Algorithms | Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) [2], Model-Based Value Iteration [3] | Enable forward planning and decision-making in model-based approaches |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES Strings [5] [6], Molecular Graphs [6] | Standardized representations of chemical structures for machine learning |

These tools collectively enable the implementation of end-to-end pipelines for drug design, from initial compound generation through experimental validation. The selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific paradigm (model-based vs. model-free) and the particular stage of the drug development process.

The choice between model-based and model-free reinforcement learning represents a fundamental trade-off between sample efficiency and asymptotic performance, between explicit planning and direct experiential learning [2]. Model-based approaches maintain stronger connections to dynamic programming traditions, leveraging learned environment dynamics to reduce the need for extensive environmental interactions [2] [1]. Model-free methods embrace a pure trial-and-error methodology, potentially achieving higher performance with sufficient data but at the cost of increased interaction requirements [2].

In drug development contexts, this paradigm selection should be guided by specific project requirements and constraints. Model-based RL offers distinct advantages when clinical data is limited, when patient safety concerns prioritize precise dosing, or when simulation environments are available for in silico testing [7] [4]. Model-free RL proves particularly valuable when exploring complex structure-activity relationships that are difficult to model explicitly, when targeting novel biological mechanisms with limited prior knowledge, or when optimizing for multiple competing properties simultaneously [5] [6].

The evolving landscape of reinforcement learning in drug discovery suggests a future of hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms, potentially combining the sample efficiency of model-based methods with the high asymptotic performance of model-free approaches [2] [9]. As both paradigms continue to mature within the broader framework of Bellman operators and dynamic programming principles [1], their strategic application promises to accelerate the drug development process while improving success rates and reducing costs.

In the field of sequential decision-making, Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) provide a fundamental mathematical framework that bridges classical dynamic programming approaches and modern reinforcement learning research. This formal model offers a structured approach to problems where outcomes are partly random and partly under the control of a decision maker, making it particularly valuable across diverse domains from robotics to healthcare [10] [11]. The MDP framework has gained significant recognition in various fields, including artificial intelligence, ecology, economics, and healthcare, by providing a simplified yet powerful representation of key elements in decision-making challenges [11].

The core significance of MDPs lies in their ability to model sequential decision-making under uncertainty, serving as a cornerstone for both dynamic programming solutions and reinforcement learning algorithms [10]. While dynamic programming provides exact solution methods for MDPs with known models, reinforcement learning extends these concepts to environments where the model is unknown, requiring interaction with the environment to learn optimal policies [12] [11]. This relationship positions MDPs as a unifying language that enables researchers and practitioners to formalize problems, compare solutions, and transfer insights across different methodological approaches, ultimately driving innovation in complex decision-making applications.

Foundational Concepts and Mathematical Framework

Core Components of MDPs

A Markov Decision Process is formally defined by a 5-tuple (S, A, Pa, Ra, γ) that provides the complete specification of a sequential decision problem [11]:

- State Space (S): The set of all possible situations or configurations in which the decision-making agent might find itself. States must be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive.

- Action Space (A): For each state s ∈ S, As represents the set of available actions that can be taken when the system is in state s.

- Transition Probabilities (Pa(s,s′)): The probability that action a in state s at time t will lead to state s′ at time t+1. This function defines the system dynamics: Pr(st+1=s′ | st=s, at=a) = Pa(s,s′).

- Reward Function (Ra(s,s′)): The immediate reward (or cost) received after transitioning from state s to state s′ due to action a.

- Discount Factor (γ): A value between 0 and 1 that determines the present value of future rewards, ensuring the total expected reward remains bounded.

The "Markov" in MDP refers to the critical Markov property: the future state and reward depend only on the current state and action, not on the complete history of states and actions [11]. This property enables efficient computation and is fundamental to both dynamic programming and reinforcement learning approaches.

Policies and Optimization Objective

The solution to an MDP is a policy (π) that specifies which action to take in each state. A policy can be deterministic (π: S → A) or stochastic (π: S → P(A)), mapping states to probability distributions over actions [11].

The goal is to find an optimal policy π* that maximizes the expected cumulative reward over time. For infinite-horizon problems, this is typically expressed as:

- Expected Discounted Reward: E[∑t=0∞ γtRat(st,st+1)] where at=π(st)

- For finite-horizon problems with horizon H, the objective becomes: E[∑t=0H-1Rat(st,st+1)]

The discount factor γ determines the relative importance of immediate versus future rewards, with values closer to 1 placing more emphasis on long-term outcomes [11].

MDPs in the Research Landscape: Connecting Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning

Algorithmic Spectrum: From Exact Solutions to Approximate Learning

The following table summarizes how MDP solutions span the continuum from classical dynamic programming to modern reinforcement learning:

Table 1: MDP Solutions Across the Dynamic Programming-Reinforcement Learning Spectrum

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Model Requirements | Computational Approach | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Dynamic Programming | Value Iteration, Policy Iteration | Complete known model (transition probabilities and reward function) | Offline computation using Bellman equations | Problems with tractable state spaces and known dynamics [11] [13] |

| Approximate Dynamic Programming | Modified Policy Iteration, Prioritized Sweeping | Complete known model | Heuristic modifications to DP algorithms for efficiency | Medium to large problems where standard DP is computationally expensive [11] |

| Model-Based Reinforcement Learning | Dyna, Monte Carlo Tree Search | Learned model or generative simulator | Learn model from interaction, then apply planning | Environments where simulation is available but exact model is unknown [11] |

| Model-Free Reinforcement Learning | Q-Learning, SARSA, Policy Gradients | No model required | Direct learning of value functions or policies from experience | Complex environments where transition dynamics are unknown or difficult to specify [12] [14] |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning | DQN, PPO, SAC, DDPG | No model required | Function approximation with neural networks | High-dimensional state spaces (images, sensor data) [12] |

The Central Role of Bellman Equations

The Bellman equations form the mathematical foundation connecting dynamic programming and reinforcement learning approaches to MDPs [13]. For a given policy π, the state-value function Vπ(s) satisfies:

Vπ(s) = ∑s' Pπ(s)(s,s')[Rπ(s)(s,s') + γVπ(s')]

The optimal value function V*(s) satisfies the Bellman optimality equation:

V(s) = maxa ∑s' Pa(s,s')[Ra(s,s') + γV(s')]

These recursive relationships enable both the exact solution methods of dynamic programming (value iteration, policy iteration) and the temporal-difference learning methods prominent in reinforcement learning [11] [13].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Population-Based Reinforcement Learning in Robotic Tasks

Recent research has demonstrated the effectiveness of MDP-based approaches in complex robotic control tasks. A 2024 benchmarking study implemented Population-Based Reinforcement Learning (PBRL) using GPU-accelerated simulation to address the data inefficiency and hyperparameter sensitivity challenges in deep RL [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Environment: Isaac Gym simulator with four challenging robotic tasks: Anymal Terrain, Shadow Hand, Humanoid, and Franka Nut Pick

- Algorithms Compared: PBRL framework benchmarked against three state-of-the-art RL algorithms - PPO, SAC, and DDPG

- Population Mechanism: Multiple policies trained concurrently with dynamic hyperparameter adjustment based on performance

- Evaluation Metrics: Cumulative reward, training efficiency, and sim-to-real transfer capability

- Sim-to-Real Transfer: Successful deployment of trained policies on a real Franka Panda robot for the Franka Nut Pick task

Key Findings: The PBRL approach demonstrated superior performance compared to non-evolutionary baseline agents across all tasks, achieving higher cumulative rewards while effectively optimizing hyperparameters during training [12]. This represents a significant advancement in applying MDP-based methods to complex robotic control problems.

Constrained MDPs for Clinical Trial Optimization

In pharmaceutical development, MDP frameworks have been adapted to address the specific challenges of clinical trial design. A novel Constrained Markov Decision Process (CMDP) approach was developed for response-adaptive procedures in clinical trials with binary outcomes [15].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: Maximize expected treatment outcomes while controlling operating characteristics such as type I error rate

- Constraint Formulation: Constraints implemented under different priors to enforce control of trial operating statistics

- Solution Method: Cutting plane algorithm with backward recursion for computationally efficient policy identification

- Comparison Baseline: Constrained randomized dynamic programming procedure

Key Findings: The CMDP approach demonstrated stronger frequentist type I error control and similar performance in other operating characteristics compared to traditional methods. When constraining only type I error rate and power, CMDP showed substantial outperformance in terms of expected treatment outcomes [15]. This application highlights how MDP frameworks can be specialized for domain-specific requirements in drug development.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Applications

Table 2: MDP Performance Comparison Across Domains and Methodologies

| Application Domain | Algorithm/Method | Performance Metrics | Comparative Results | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic Control [12] | Population-Based RL (PBRL) | Cumulative reward, Training efficiency | Superior to PPO, SAC, DDPG baselines | Enhanced exploration, dynamic hyperparameter optimization |

| Robotic Control [12] | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | Cumulative reward | Baseline performance | Stable training, reliable convergence |

| Robotic Control [12] | Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) | Cumulative reward | Competitive but inferior to PBRL | Sample efficiency, off-policy learning |

| Robotic Control [12] | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) | Cumulative reward | Lowest performance among tested algorithms | Continuous action spaces, deterministic policies |

| Clinical Trials [15] | Constrained MDP (CMDP) | Expected outcomes, Type I error control | Stronger error control vs. constrained randomized DP | Direct constraint satisfaction, optimality guarantees |

| Clinical Trials [15] | Thompson Sampling | Expected outcomes, Computational efficiency | Simpler implementation but lower performance | Computational simplicity, ease of deployment |

| Network Security [16] | MDP-based Detection | Accuracy, Response time | 94.3% detection accuracy | Adaptability to unknown attacks, interpretability |

| Medical Decision Making [13] | MDP vs. Standard Markov | Computation time, Solution quality | Equivalent optimal policies with significantly faster computation (MDP) | Computational efficiency for sequential decisions |

Computational Efficiency Analysis

MDP frameworks demonstrate significant computational advantages for sequential decision problems compared to naive enumeration approaches:

In a study comparing MDPs to standard Markov models for optimal timing of living-donor liver transplantation, both models produced identical optimal policies and total life expectancies. However, the computation time for solving the MDP model was significantly smaller than for solving the Markov model [13]. This efficiency advantage becomes increasingly pronounced as problem complexity grows, making MDPs particularly valuable for problems with numerous embedded decision points.

For the complex problem of cadaveric organ acceptance/rejection decisions, a standard Markov simulation model would need to evaluate millions of possible policy combinations, becoming computationally intractable. In contrast, the MDP framework provides efficient exact solutions through dynamic programming algorithms like value iteration and policy iteration [13].

Research Toolkit: Essential Components for MDP Implementation

Methodological Components

Table 3: Essential Research Components for MDP Implementation

| Component | Function | Examples/Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| State Representation | Encodes all relevant environment information | Discrete states, continuous feature vectors, neural network embeddings [11] |

| Reward Engineering | Defines optimization objective through immediate feedback | Sparse rewards, shaped rewards, constraint penalties [15] |

| Transition Model | Represents system dynamics | Explicit probability tables, generative simulators, neural network approximations [11] |

| Value Function | Estimates long-term value of states or state-action pairs | Tabular representation, linear function approximation, deep neural networks [11] |

| Policy Representation | Determines action selection mechanism | Deterministic policies, stochastic policies, parameterized neural networks [11] |

| Exploration Strategy | Balances exploration of unknown states with exploitation of current knowledge | ε-greedy, Boltzmann exploration, optimism under uncertainty, posterior sampling [12] |

Computational Infrastructure

Successful implementation of MDP-based solutions, particularly in complex domains, requires appropriate computational resources:

- GPU-Accelerated Simulation: Modern RL approaches leverage GPU-based simulators like Isaac Gym to run thousands of parallel environments, dramatically reducing training times for robotic control tasks [12].

- Efficient Backward Recursion: For exact solution of finite-horizon MDPs, optimized backward recursion implementations with careful state storage management enable solution of clinically relevant problems in reasonable timeframes [15].

- Parallelization Frameworks: Population-based methods exploit parallel computation to train multiple policies simultaneously, enabling evolutionary optimization of hyperparameters and policies [12].

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the unified MDP framework connecting dynamic programming and reinforcement learning methodologies:

MDP Unified Framework Diagram

The Markov Decision Process framework continues to serve as a fundamental unifying paradigm for sequential decision problems, bridging the historical developments of dynamic programming with modern advances in reinforcement learning. As evidenced by the diverse applications across robotics, healthcare, and clinical trials, MDPs provide a mathematically rigorous yet flexible foundation for modeling and solving complex decision problems under uncertainty.

The ongoing research in areas such as constrained MDPs for clinical trials and population-based RL for robotic control demonstrates how the core MDP framework adapts to address domain-specific challenges while maintaining its theoretical foundations. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this continuum from dynamic programming to reinforcement learning within the MDP framework enables more informed methodological choices and facilitates cross-disciplinary innovation.

As computational capabilities continue to advance and new algorithmic approaches emerge, the MDP framework remains positioned as an essential tool for tackling the increasingly complex sequential decision problems across scientific and industrial domains.

Dynamic Programming (DP) represents a cornerstone of algorithmic problem-solving for complex, sequential decision-making processes. Founded on Bellman's principle of optimality, DP provides a mathematical framework for decomposing multi-stage problems into simpler, nested subproblems. The core insight—that an optimal policy consists of optimal sub-policies—revolutionized our approach to everything from logistics and scheduling to financial modeling and beyond. Bellman's equation provides the recursive mechanism that makes this decomposition possible, enabling efficient computation of value functions that guide optimal decision-making [17].

In contemporary artificial intelligence research, DP's significance extends far beyond its original applications—it serves as the theoretical bedrock for modern Reinforcement Learning (RL). While these fields have often developed in parallel within different research communities, they are unified by the same mathematical framework: Bellman operators and their variants [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between classical dynamic programming approaches and their reinforcement learning successors, examining their respective performance characteristics, data requirements, and applicability to real-world problems, particularly focusing on domains requiring perfect-information solutions.

Theoretical Foundations: Bellman's Equations and the DP-RL Spectrum

The Bellman Equation: A Recursive Revolution

The Bellman equation formalizes the principle of optimality through a recursive relationship that defines the value of being in a particular state. For a state value function under a policy π, it can be expressed as:

Vπ(s) = E(R(s,a) + γVπ(s'))

where Vπ(s) represents the value of state s, R(s,a) is the immediate reward received after taking action a in state s, γ is a discount factor balancing immediate versus future rewards, and s' is the next state [17]. This recursive formulation elegantly captures the essence of sequential decision-making: the value of your current state depends on both your immediate reward and the discounted value of wherever you land next.

The true power of this formulation emerges in the Bellman optimality equation, which defines the maximum value achievable from any state:

V*(s) = max_a(R(s,a) + γV*(s'))

This equation forms the basis for optimal policy discovery, as it explicitly defines how to choose actions at each state to maximize cumulative rewards [17]. The conceptual breakthrough was recognizing that even though long-term planning problems appear overwhelmingly complex, they can be solved one step at a time through this recursive relationship.

The DP-RL Spectrum: A Unified Perspective

Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning represent points on a continuum of sequential decision-making approaches, unified through Bellman operators:

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their information requirements and computational strategies. Classical Dynamic Programming methods, including value iteration and policy iteration, operate under the assumption of a perfect environment model—complete knowledge of transition probabilities and reward structures. These algorithms employ a full-backup approach, systematically updating value estimates for all states simultaneously through iterative application of the Bellman equation [18].

Approximate Dynamic Programming (ADP) represents an intermediate approach, utilizing estimated model dynamics from data rather than assuming perfect a priori knowledge. This methodology bridges the gap between theoretical DP and practical applications where complete models are unavailable [1].

Reinforcement Learning completes this spectrum by eliminating the need for explicit environment models altogether. RL algorithms learn directly from sample trajectories—sequences of states, actions, and rewards—through interaction with the environment. Temporal-Difference learning methods, such as Q-learning, implement stochastic approximation to the Bellman equation, while modern deep RL approaches represent neural implementations of classical ADP techniques [1].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Across Domains

Dynamic Pricing Markets: A Controlled Comparison

Recent research has directly compared classical data-driven DP approaches against modern RL algorithms in dynamic pricing environments, providing valuable insights into their relative performance characteristics across different data regimes [19].

Experimental Protocol: The study implemented a finite-horizon dynamic pricing framework for airline ticket markets, examining both monopoly and duopoly competitive scenarios. The experimental design controlled for environmental factors while varying the amount of training data available to each algorithm. DP methods utilized observational training data to estimate model dynamics, while RL agents learned directly through environment interaction. Performance was evaluated based on achieved rewards, data efficiency, and computational requirements across 10, 100, and 1000 training episodes [19].

Algorithm Specifications:

- DP Methods: Data-driven versions utilizing estimated transition probabilities

- RL Algorithms: TD3, DDPG, PPO, SAC implementations

- Evaluation Metric: Percentage of optimal solution achieved

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Dynamic Pricing Markets

| Data Regime | Best Performing Method | % of Optimal Solution | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few Data (<10 episodes) | Data-driven DP | ~85-90% | Highly competitive with limited data |

| Medium Data (~100 episodes) | PPO (RL) | ~80-85% | Superior to DP with sufficient exploration |

| Large Data (~1000 episodes) | TD3, DDPG, PPO, SAC | >90% | Asymptotic near-optimal performance |

The results demonstrate a clear tradeoff between data efficiency and asymptotic performance. While DP methods maintain strong competitiveness with minimal data, modern RL algorithms achieve superior performance given sufficient training episodes [19].

Computational Efficiency and Solution Quality

Table 2: Method Characteristics and Computational Requirements

| Method Category | Information Requirements | Computational Complexity | Solution Guarantees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical DP | Perfect model knowledge | High (curse of dimensionality) | Optimal with exact computation |

| Data-driven DP | Estimated transition probabilities | Medium to High | Near-optimal with accurate estimates |

| Reinforcement Learning | Sample trajectories | Variable (training vs. execution) | Asymptotically optimal with sufficient exploration |

Traditional DP algorithms provide strong theoretical guarantees—including convergence to optimal policies—but face significant computational challenges, most notably the "curse of dimensionality" where state space size grows exponentially with problem complexity [20]. Recent innovations in DP methodologies have focused on mitigating these limitations through hybrid approaches.

One promising direction combines exact and approximate methods, such as Branch-and-Bound-regulated Dynamic Programming, which uses heuristic approximations to limit the state space of the DP process while maintaining solution quality guarantees [20]. Similarly, Non-dominated Sorting Dynamic Programming integrates Pareto dominance concepts from multi-objective optimization into the DP framework, demonstrating superior performance compared to genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization on benchmark problems [21].

Methodological Toolkit: Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Core Algorithmic Components

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DP/RL Comparison Studies

| Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Value Function Estimator | Tracks expected long-term returns | Tabular representation, Neural networks, Linear function approximators |

| Policy Improvement Mechanism | Enhances decision-making strategy | Greedy improvement, Policy gradient, Actor-critic architectures |

| Environment Model | Simulates state transitions and rewards | Known dynamics model, Estimated from data, Sample-based approximation |

| Exploration Strategy | Balances information gathering vs. reward collection | ε-greedy, Boltzmann exploration, Optimism under uncertainty |

Standardized Evaluation Workflow

A robust experimental protocol for comparing DP and RL methodologies follows this structured approach:

Phase 1: Problem Formulation - Define state space, action space, reward function, and transition dynamics appropriate to the domain. For perfect-information DP applications, this includes specifying known transition probabilities.

Phase 2: Algorithm Implementation - Implement DP methods (value iteration, policy iteration) alongside selected RL algorithms (Q-learning, PPO, DDPG). Ensure consistent value function representation and initialization across methods.

Phase 3: Training & Evaluation - Train each algorithm under controlled conditions, varying key parameters such as training data volume. Evaluate performance on standardized metrics including convergence speed, solution quality, and computational requirements.

The comparative analysis between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological choices significantly impact practical outcomes. Classical DP approaches, grounded in Bellman's equations, remain indispensable for problems with well-specified models and moderate state spaces, providing guaranteed optimality and data efficiency. Their transparent operation and strong theoretical foundations make them particularly valuable in safety-critical domains where solution verifiability is essential.

Conversely, modern RL methods excel in environments where complete model specification is impractical or impossible, leveraging sample-based learning and function approximation to tackle extremely complex problems. While requiring substantially more data and computational resources for training, their flexibility and asymptotic performance make them increasingly attractive for real-world applications ranging from robotics to revenue management.

For research professionals and drug development specialists, this comparison suggests a contingency-based approach to algorithm selection: DP-derived methods for data-scarce environments with reliable models, and RL approaches for data-rich environments with complex, poorly specified dynamics. Future research directions likely include hybrid approaches that combine the theoretical guarantees of DP with the flexibility of RL, potentially through improved model-based reinforcement learning techniques. As both fields continue to evolve through their shared foundation in Bellman's equations, this cross-pollination promises to further expand the frontiers of sequential decision-making across scientific domains.

In complex fields like drug development, where information is often scarce and sensor data is inherently noisy, choosing the right algorithmic approach for sequential decision-making is paramount. This guide objectively compares two dominant paradigms: classical Data-driven Dynamic Programming (DP) and modern Reinforcement Learning (RL), with a specific focus on their performance in data-limited and noisy environments.

Traditional DP methods rely on a "forecast-first-then-optimize" principle, requiring a pre-estimated model of the environment's dynamics [19]. In contrast, model-free RL agents learn optimal policies directly through interaction with the environment, balancing exploration of new actions with exploitation of known rewards [9] [19]. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each approach is the first step in mastering information-scarce scenarios.

Core Challenge: Limited and Noisy Information

A fundamental challenge in applying RL to real-world problems like autonomous driving or robotics is the "reality gap": policies trained in simulation often fail when deployed due to imperfect sensors, transmission delays, or external attacks that corrupt observations [22]. This problem is formalized as a Decentralized Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (Dec-POMDP), where agents never receive perfect state information [22].

In a "fully noisy observation" environment, all external sensor readings (e.g., camera images, LiDAR) are continuously corrupted, for instance, by Gaussian noise, and the agent never accesses a clean observation during its entire training cycle [22]. This distinguishes the problem from standard partial observability, where some clean information is available.

Comparative Analysis: DP vs. RL in Dynamic Pricing

A 2025 study provides a direct, quantitative comparison of data-driven DP and RL methods within a dynamic pricing framework for an airline ticket market, a domain characterized by complex, changing market dynamics [19]. The experimental setup involved monopoly and duopoly markets, evaluating performance based on the amount of available training data (episodes).

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

- Market Simulation: A flexible, open-source airline ticket market simulation was developed, modeling customer demand and competitor reactions.

- Algorithm Training:

- DP Methods: Required observational data to first estimate the underlying model dynamics (e.g., state transition probabilities, reward functions). The optimized policy was then derived from this estimated model.

- RL Methods: Model-free algorithms (e.g., PPO, DDPG, SAC, TD3) interacted directly with the simulation environment, learning policies through trial and error without an explicit world model.

- Evaluation Metric: The primary performance metric was the average reward achieved by each method's policy, measured against the optimal solution [19].

Performance Results and Data Efficiency

The study's core finding is that the superiority of DP or RL is highly dependent on the volume of available data. The results are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DP and RL Algorithms Across Data Regimes

| Data Regime | Best Performing Methods | Performance Achievement | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few Data (~10 episodes) | Data-driven Dynamic Programming | Highly Competitive | DP methods remain strong and sample-efficient when data is scarce [19]. |

| Medium Data (~100 episodes) | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | Outperforms DP | RL begins to show an advantage, with PPO providing the best results in this regime [19]. |

| Large Data (~1000 episodes) | TD3, DDPG, PPO, SAC | ~90%+ of Optimal | Multiple RL algorithms perform similarly at a high level, achieving near-optimal rewards [19]. |

This comparison reveals a critical "switching point": DP methods are more data-efficient initially, but with sufficient data (around 100 episodes in this study), RL algorithms ultimately learn superior policies by not being constrained by an imperfect, estimated model of the environment [19].

Advanced RL Solutions for Noisy Information

To address the critical challenge of fully noisy observations, researchers have developed sophisticated algorithms that move beyond simple noise injection. The following workflow visualizes a state-of-the-art method for robust learning in such environments.

The PLANET Method

The PLANET (Policy Learning under Fully Noisy Observations via DeNoising REpresentation NeTwork) method is designed for multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) in environments where all external observations are noisy [22].

- Core Innovation: PLANET does not require any clean observations. Instead, it takes two independent, noisy observations of the environment at each timestep.

- Self-Supervised Denoising: The second observation serves as a surrogate ground truth to train denoising representation networks. These networks learn to extract the underlying "noise characteristics and motion laws" to produce a clean observation representation [22].

- Integration: This cleaned representation is then fed into standard MARL algorithms (e.g., QMIX, VDN), enabling them to learn effective policies where they would otherwise fail [22].

Performance of Robust RL Algorithms

Experiments on tasks like cooperative capture and ball pushing demonstrated that PLANET allows MARL algorithms to successfully mitigate the effects of noise and learn effective policies, significantly outperforming standard algorithms that lack this denoising capability [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers aiming to implement and experiment with the RL methods discussed, the following tools and frameworks are essential.

Table 2: Key Research Tools for Reinforcement Learning

| Tool / Material | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Noisy/Limited Info |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ray RLlib [9] | RL Framework | Scalable training for a wide variety of RL algorithms. | Facilitates large-scale experiments comparing sample efficiency. |

| OpenAI Gym [9] | Environment API | Provides a standardized interface for diverse RL environments. | Allows for custom environment creation with configurable noise models. |

| Isaac Gym [9] | Simulation Environment | GPU-accelerated physics simulation for robotics. | Enables efficient, massive parallel data collection, mitigating data scarcity. |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow [9] | Deep Learning Library | Provides building blocks for custom neural networks. | Essential for implementing novel components like PLANET's denoising networks. |

| PLANET Denoising Network [22] | Algorithmic Component | Self-supervised network for cleaning fully noisy observations. | Core reagent for robust learning in noisy environments. |

| Smart Buildings Control Suite [23] | Domain-Specific Simulator | Physics-informed simulator for building HVAC control. | Provides a high-fidelity testbed for sample-efficient and robust RL. |

The choice between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning is not absolute but contextual, hinging on the data and noise characteristics of the problem.

- For Data-Scarce Problems: Data-driven Dynamic Programming remains a robust and highly competitive choice, often providing more reliable results with fewer than 100 training episodes [19].

- For Data-Rich Problems: Modern RL algorithms like PPO, SAC, and TD3 unlock superior performance, capable of learning complex policies that are not limited by an estimated model, achieving over 90% of optimal rewards with sufficient data [19].

- For Inherently Noisy Environments: Specialized RL methods like PLANET are necessary. They provide a pathway to robustness by explicitly modeling and filtering noise, which is a critical requirement for real-world deployment in domains from autonomous systems to drug development [22].

In the broader taxonomy of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML) represents a fundamental subset dedicated to enabling systems to learn from data without explicit programming. Within ML, Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Dynamic Programming (DP) stand as two powerful, interconnected paradigms for solving sequential decision-making problems under uncertainty [19]. While RL is a type of machine learning where an agent learns by interacting with its environment to maximize cumulative rewards, classical DP provides a suite of well-understood, model-based algorithms for optimizing such sequential processes [24] [25]. The relationship between these approaches is a subject of ongoing research and practical importance, especially in complex, data-rich domains like drug development. This guide objectively compares their performance, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed to inform their choice of approach for specific challenges.

The Conceptual Hierarchy: From AI to DP and RL

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between AI, ML, DP, and RL, clarifying their positions within the broader AI hierarchy.

This hierarchy shows that RL is a distinct subset of Machine Learning, whereas DP is a broader methodology for solving sequential decision problems. Their paths converge on the same class of problems but originate from different branches of the AI tree, leading to fundamental differences in their application requirements and capabilities.

Experimental Comparison: A Dynamic Pricing Case Study

A pivotal 2025 study provides a direct, empirical comparison of data-driven DP and modern RL algorithms within a controlled dynamic pricing environment, simulating scenarios like airline ticket sales [19].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The study was designed to evaluate how DP and RL methods perform under varying data availability conditions, a critical consideration for real-world applications.

- Objective: Maximize long-term cumulative revenue in a finite-horizon dynamic pricing market.

- Environment: Simulated airline ticket market with incomplete information, involving stochastic consumer demand and, in extended setups, competitor reactions.

- Algorithms Tested:

- Data-driven DP: Used historical data to estimate underlying market dynamics (demand transitions, rewards) and then applied classical DP for optimization.

- Model-free Deep RL: Several state-of-the-art algorithms, including PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization), DDPG (Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient), TD3 (Twin Delayed DDPG), and SAC (Soft Actor-Critic), which learned policies directly through environment interaction.

- Training Regimes: Performance was evaluated across three distinct data regimes:

- Few Data: ~10 training episodes.

- Medium Data: ~100 training episodes.

- Large Data: ~1000 training episodes.

- Evaluation Metric: The primary key performance indicator (KPI) was the average reward achieved, reported as a percentage of the optimal reward achievable with full model knowledge.

Performance Results and Data Efficiency

The experimental results clearly delineate the strengths and weaknesses of each approach based on data availability. The following table summarizes the quantitative findings from the monopoly market setup [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DP and RL Algorithms in a Dynamic Pricing Monopoly

| Data Regime | Data-Driven DP | PPO | DDPG / TD3 / SAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few Data (~10 episodes) | Highly competitive; often superior performance. | Moderate performance. | Lower performance due to insufficient training. |

| Medium Data (~100 episodes) | Outperformed by leading RL methods. | Best performing algorithm. | Good and improving performance. |

| Large Data (~1000 episodes) | Generally outperformed. | Very high performance (>90% of optimal). | Best performing group; similarly high performance (>90% of optimal). |

A key finding was the existence of a "switching point" in data volume, around 100 episodes in this study, where the best RL methods began to consistently outperform the well-established DP techniques [19]. This highlights the sample efficiency of DP versus the ultimate performance potential of RL.

Validation from Other Domains: Vehicle Routing Problems

These findings are corroborated by research in other complex domains, such as Dynamic Vehicle Routing Problems (DVRPs). A comparative study of value-based (e.g., NNVFA) and policy-based (e.g., NNPFA) RL methods, which can be seen as analogous to the DP/RL spectrum, found that the performance of linear versus neural network policies is highly dependent on the specific problem structure and complexity [26]. This reinforces the principle that there is no single superior algorithm for all scenarios, and choice must be context-driven.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for DP and RL Implementation

For scientists embarking on implementing DP or RL experiments, the following suite of software tools and libraries is indispensable.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DP & RL Experiments

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Provides the foundational infrastructure for building and training neural networks used as function approximators in Deep RL. |

| PyTorch Frame [27] | Tabular Deep Learning Library | Democratizes deep learning for heterogeneous tabular data, useful for pre-processing state representations in RL or structuring state spaces in DP. |

| DeepTabular [28] | Tabular Deep Learning Library | Offers a suite of models (e.g., FTTransformer, TabTransformer) for regression/classification, which can be integrated into broader RL or DP pipelines. |

| PyTorch Tabular [29] | Tabular Deep Learning Library | Simplifies the application of deep learning to structured data, facilitating quick prototyping and experimentation. |

| Stable-Baselines3 | RL Library | Provides reliable, well-tested implementations of standard RL algorithms like PPO, DDPG, and SAC for experimental comparison. |

| Digital Twin Simulation | Modeling & Simulation | A critical auxiliary environment for safe, efficient training and testing of RL agents before real-world deployment, mitigating risks [19] [24]. |

Experimental Workflow for Comparing DP and RL

To ensure reproducible and objective comparisons between DP and RL approaches, researchers should adhere to a structured experimental workflow. The following diagram outlines a standardized protocol.

This workflow emphasizes the initial critical choice point: whether a high-fidelity model of the environment is available. If a model is known and tractable, DP is a viable and often highly data-efficient path. If the model is unknown or too complex, RL becomes the necessary approach, though it demands greater computational and data resources.

The dichotomy between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning is not one of outright superiority but of contextual fitness. The experimental evidence consistently shows that data-driven DP remains a robust and highly sample-efficient choice for problems with limited data or where a model can be reliably estimated [19]. In contrast, modern RL algorithms, particularly policy-based methods like PPO and value-based methods like DDPG/TD3, unlock higher performance ceilings when abundant data and computational resources are available [19] [26].

For the field of drug development, where data can be scarce in early stages but immensely complex and high-dimensional in later stages, this suggests a hybrid future. Researchers might leverage DP-based approaches for initial optimization with limited preclinical data and gradually incorporate or transition to RL as clinical trial and biomolecular simulation data accumulate. The ongoing maturation of RL, including addressing challenges like explainability and algorithmic safety [19] [24], will further solidify its role as an indispensable tool in the AI hierarchy for solving the most challenging sequential decision-making problems in science and industry.

From Theory to Therapy: Applying DP and RL in Drug Discovery and Healthcare

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates innovative strategies to prolong the efficacy of existing antibiotics. Within computational therapeutics, two dominant paradigms have emerged for optimizing antibiotic cycling protocols: dynamic programming (DP) for environments with perfect information, and reinforcement learning (RL) for scenarios characterized by uncertainty. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, focusing on their theoretical foundations, experimental performance, and practical applicability in designing evolution-based therapies to combat AMR.

Antimicrobial resistance was associated with an estimated 4.95 million global deaths in 2019, presenting a critical public health threat that demands novel intervention strategies [30]. Beyond the discovery of new drugs, researchers are developing evolution-based therapies that strategically use existing antibiotics to slow, prevent, or reverse resistance evolution [31]. A key phenomenon exploited by these approaches is collateral sensitivity—when resistance to one antibiotic concurrently increases susceptibility to another—creating evolutionary trade-offs that can be strategically exploited through carefully designed treatment schedules [32].

Computational optimization methods are essential for identifying these effective schedules. Dynamic programming approaches operate under perfect information, requiring complete knowledge of bacterial evolutionary landscapes. In contrast, reinforcement learning methods learn optimal policies through interaction with the environment, making them suitable for situations where underlying dynamics are partially observed or uncertain [33]. This guide objectively compares the performance, data requirements, and implementation of these competing frameworks.

Methodological Comparison: Foundational Principles

Dynamic Programming Framework for Perfect-Information Scenarios

Dynamic programming approaches for antibiotic cycling rely on complete characterizations of bacterial fitness landscapes and collateral sensitivity networks.

Mathematical Formalization: DP models are typically formulated as multivariable switched systems of ordinary differential equations that instantaneously model population dynamics when a specific drug is administered [31]. The core relationship describing evolutionary outcomes can be summarized as:

- R:CS → S: A resistant (R) population exhibits collateral sensitivity (CS) to a drug, transitioning to a susceptible (S) state.

- S:CR → R: A susceptible (S) population exhibits cross-resistance (CR) to a drug, transitioning to a resistant (R) state [31].

Data Requirements: These methods require exhaustive, pre-defined datasets of collateral sensitivity patterns, such as Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) fold-changes across multiple antibiotics for resistant bacterial variants [31]. The model assumes perfect knowledge of how resistance mutations to one antibiotic alter susceptibility to others.

Optimization Process: Using this complete fitness landscape, DP algorithms compute optimal state transitions (drug switches) that minimize the long-term risk of multidrug resistance emergence, typically by steering bacterial populations through evolutionary trajectories where they remain susceptible to at least one drug in the cycle [31].

Reinforcement Learning Framework for Imperfect Information

Reinforcement learning approaches frame antibiotic cycling as a sequential decision-making problem where an agent learns optimal policies through environmental interaction.

Mathematical Foundation: The problem is formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by states (e.g., bacterial population characteristics), actions (antibiotic selection), and rewards (e.g., negative population fitness) [30]. The agent learns a policy that maps states to actions to maximize cumulative reward.

Learning Paradigm: Unlike DP, RL agents do not require perfect prior knowledge of the fitness landscape. They learn effective drug cycling policies through trial-and-error, adapting to noisy, limited, or delayed measurements of population fitness [30]. This model-free characteristic is a key distinction from model-based DP.

Algorithmic Variants: Recent applications use model-free RL and Deep RL to manage complex systems with unknown tipping points, employing techniques like off-policy evaluation and safe RL to handle challenges like data scarcity and high-stakes decision-making [33].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning for Drug Cycling

| Feature | Dynamic Programming | Reinforcement Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Information Requirement | Perfect information of fitness landscapes and collateral sensitivity networks [31] | Can operate with partial, noisy, or delayed observations [30] |

| System Model | Requires a pre-specified, accurate model of evolutionary dynamics [31] | Can learn from interaction without an explicit system model (model-free RL) [33] |

| Optimization Approach | Computes optimal policies through backward induction on the known model | Learns policies through trial-and-error and experience replay [30] |

| Handling Uncertainty | Limited to stochastic models with known probability distributions | Robust to model misspecification; can handle non-stationary environments [33] |

Experimental Performance and Quantitative Comparison

Performance Metrics in Simulated Environments

Experimental validation of these approaches typically occurs in simulated environments parameterized with empirical fitness data. Key performance metrics include time to resistance emergence, overall population fitness, and the ability to suppress multidrug-resistant variants.

DP Performance: Computational frameworks based on DP formalisms can successfully identify antibiotic sequences that avoid triggering multidrug resistance by navigating subspaces of the evolutionary landscape [31]. For example, DP models can highlight specific drug combinations and sequences that lead to treatment failure, providing conservative strategies that would likely fail if other clinical factors were considered [31].

RL Performance: Studies demonstrate that RL agents can outperform naive treatment paradigms (such as fixed cycling) at minimizing population fitness over time [30]. In simulations with E. coli and a panel of 15 β-lactam antibiotics, RL agents approached the performance of the optimal drug cycling policy, even when stochastic noise was introduced to fitness measurements [30].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Based on Published Studies

| Criterion | Dynamic Programming (Collateral Sensitivity Framework) | Reinforcement Learning (Informed Policy) |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Pathogen | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA01) [31] | Escherichia coli [30] |

| Antibiotic Panel Size | 24 antibiotics [31] | 15 β-lactam antibiotics [30] |

| Key Performance Outcome | Identifies sequences avoiding multi-resistance; highlights failure scenarios [31] | Minimizes population fitness; approaches optimal policy performance [30] |

| Robustness to Noise | Not explicitly evaluated (assumes perfect data) | Maintains effectiveness with stochastic noise in fitness measurements [30] |

| Scalability | Scalable strategy for navigating evolutionary landscapes [31] | Effective in arbitrary fitness landscapes of up to 1,024 genotypes [30] |

The Critical Challenge of Dynamic Collateral Sensitivity Profiles

A significant challenge for perfect-information DP models is the recently demonstrated dynamic nature of collateral sensitivity profiles. Laboratory evolution experiments in Enterococcus faecalis reveal that collateral effects are not static but change over evolutionary time [32].

Temporal Dynamics: Research shows that collateral resistance often dominates during early adaptation phases, while collateral sensitivity becomes increasingly likely with further selection and stronger resistance [32]. These profiles are highly idiosyncratic, varying based on the selecting drug and the testing drug.

Implications for DP: These findings indicate that optimal drug scheduling may require exploitation of specific, time-dependent windows where collateral sensitivity is most pronounced [32]. Static fitness landscapes used in traditional DP may become outdated, leading to suboptimal cycling recommendations. This necessitates a dynamic Markov decision process (d-MDP) that incorporates temporal changes in collateral profiles [32].

Dynamic Programming vs. Reinforcement Learning Workflows: This diagram contrasts the fundamental operational differences between DP and RL approaches. DP requires a complete collateral sensitivity matrix as input, while RL operates on sequential fitness measurements and learns through feedback.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Frameworks

Implementing DP or RL strategies for antibiotic cycling requires specific computational tools and experimental resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Collateral Sensitivity Heatmap Data | Experimental dataset of MIC fold-changes for resistant strains against a panel of antibiotics [31]. | Essential for parameterizing DP models; provides the perfect-information landscape. |

| Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) | Protocol for evolving bacterial populations under antibiotic pressure to generate resistant strains for profiling [32]. | Generates empirical data on resistance evolution and collateral effects for both DP and RL. |

| Open-Source Computational Platform | Intuitive, accessible in silico tool for data-driven antibiotic selection based on mathematical formalization [31]. | Implements DP framework for predicting sequential therapy failure. |

| Reinforcement Learning Agent | AI algorithm (e.g., using Proximal Policy Optimization) that learns cycling policies through environmental interaction [30]. | Core component for model-free optimization under uncertainty. |

| Ternary Diagram Analysis | Analytical framework for visualizing and identifying optimal 3-drug combinations based on CS/CR/IN proportions [31]. | Used with DP to find drug combinations near predefined therapeutic targets. |

General Workflow for Optimizing Antibiotic Cycling: This workflow outlines the key steps for developing data-driven antibiotic cycling strategies, from initial phenotypic profiling to in vitro validation, a process applicable to both DP and RL approaches.

Discussion: Strategic Selection of a Computational Framework

The choice between dynamic programming and reinforcement learning for optimizing antimicrobial drug cycling hinges on the specific research context and data availability.

When to Prefer Dynamic Programming: DP is ideal when researchers have access to comprehensive, high-quality collateral sensitivity maps and seek a conservative, interpretable strategy. Its strength lies in providing a formal guarantee of optimality under the assumption of perfect information and can definitively highlight therapy sequences prone to failure [31].

When to Prefer Reinforcement Learning: RL is superior in more realistic clinical scenarios where fitness landscapes are incomplete, noisy, or non-stationary. Its ability to learn from limited, delayed feedback and adapt to changing environments makes it a robust and flexible approach for long-term resistance management [30] [33]. This is particularly relevant given the newly understood dynamic nature of collateral sensitivity profiles [32].

The future of computational antibiotic optimization likely lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the theoretical guarantees of DP where information is reliable, while incorporating the adaptive, learning capabilities of RL to manage uncertainty and temporal evolution in bacterial fitness landscapes.

The prevention of chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease (CVD), represents a long-term combat requiring continual fine-tuning of treatment strategies to adapt to the progressive course of disease. While traditional risk prediction models can identify patients at elevated risk, they offer limited assistance in tailoring dynamic preventive strategies over decades of care. Without comprehensive insights, clinical prescriptions may prioritize short-term gains but deviate from trajectories toward long-term survival [34]. This challenge frames a critical computational question: how can we optimize sequential decision-making under uncertainty when managing chronic conditions?

This question sits at the heart of a broader methodological debate between Dynamic Programming (DP) and Reinforcement Learning (RL). Dynamic Programming provides a mathematical framework for solving sequential decision problems where the underlying model of the environment (including transition probabilities) is fully known [18] [35]. In healthcare, this would require perfect knowledge of how each drug dose affects every patient's physiology over time—information rarely available in clinical practice. Conversely, Reinforcement Learning learns optimal policies directly from interaction with the environment, without requiring a perfect model upfront [35]. This fundamental difference makes RL particularly suited for healthcare applications where physiological responses vary significantly across individuals and perfect models remain elusive.

The Duramax framework emerges at this intersection, representing an evidence-based RL approach optimized for long-term preventive strategies. By learning from massive-scale real-world treatment trajectories, it addresses a critical gap in current care: the inability of static protocols to adapt therapies to individual trajectories of lipid response, comorbidities, and treatment tolerance [34].

Methodological Foundation: DP vs. RL in Healthcare

Fundamental Computational Differences

The distinction between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning represents a fundamental divide in sequential decision-making approaches. Dynamic Programming algorithms, including policy iteration and value iteration, operate on the principle of optimality for problems with known dynamics. They require a complete and accurate model of the environment, including all state transition probabilities and reward structures [18] [35]. This makes DP powerful for well-defined theoretical problems but limited in complex, real-world domains where such perfect models are unavailable.

Reinforcement Learning, in contrast, does not require a pre-specified model of the environment. Instead, RL agents learn optimal behavior through direct interaction with their environment, discovering which actions yield the greatest cumulative reward through trial and error [35]. This model-free approach comes at the cost of typically requiring more data than DP methods, but offers greater adaptability to complex, imperfectly understood environments.

The following table summarizes the key distinctions between these approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning

| Feature | Dynamic Programming | Reinforcement Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Environment Knowledge | Requires complete model of state transitions and rewards | Learns directly from environment interaction without a perfect model |

| Data Requirements | Lower data requirements when model is known | Typically requires substantial interaction data |

| Convergence | Deterministic, guaranteed optimal solution for known MDPs | Stochastic, convergence not always guaranteed |

| Real-World Adaptability | Limited when environment dynamics are imperfectly known | High adaptability to complex, uncertain environments |

| Healthcare Application | Suitable for well-understood physiological processes with known dynamics | Ideal for personalized treatment where individual responses vary |

The Markov Decision Process Framework

Both DP and RL typically operate within the Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework, which formalizes sequential decision-making problems [34]. In healthcare, an MDP can be defined where:

- States (s) represent individual patient risk profiles including lipid levels, medical history, and comorbidities

- Actions (a) correspond to clinical decisions such as drug choices, dosage adjustments, or timing of follow-ups

- Transition probabilities P(s′∣s,a) capture how patient states evolve following interventions

- Rewards R(s,a) quantify immediate outcomes such as lipid reduction balanced against adverse effects

Long-term CVD prevention is naturally formulated as an MDP, where the objective is to find a policy π that maps states to actions to maximize the cumulative expected reward over potentially decades of care [34].

The Duramax Framework: Design and Implementation

Architecture and Learning Approach

Duramax is a specialized RL framework designed to optimize long-term lipid-modifying therapy for CVD prevention. Its architecture addresses key challenges in applying RL to chronic disease management: modeling delayed rewards (avoiding CVD events decades later), ensuring safety in high-stakes decisions, and maintaining clinical interpretability [34].

The framework employs an off-policy learning approach that can learn from historical treatment trajectories without requiring online exploration on real patients. This is crucial for healthcare applications where random exploration could potentially harm patients. Duramax learns from suboptimal demonstrations—real-world clinician decisions of varying quality—and improves upon them by optimizing for long-term outcomes rather than mimicking all demonstrated actions [36] [37].

A key innovation in Duramax is its handling of imperfect demonstration data. Unlike approaches that combine distinct supervised and reinforcement losses, Duramax uses a unified objective that normalizes the Q-function, reducing the Q-values of actions unseen in the demonstration data. This makes the framework robust to noisy real-world data where suboptimal decisions are inevitable [36].

Experimental Setup and Data Infrastructure

The development and validation of Duramax leveraged one of the most comprehensive real-world datasets for studying lipid management:

Table 2: Dataset Characteristics for Duramax Development and Validation

| Dataset Component | Development Cohort | Validation Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Population | 62,870 patients from Hong Kong Island | 454,361 patients from Kowloon and New Territories |

| Observation Period | 3,637,962 treatment months | 29,758,939 treatment months |

| Data Source | Hong Kong Hospital Authority (2004-2019) | Hong Kong Hospital Authority (2004-2019) |

| Drug Diversity | 214 different lipid-modifying drugs and combinations | Not specified |

| Key Inclusion | Primary CVD prevention, high completeness of lipid tests and prescriptions | Primary CVD prevention |

The data curation process selected approximately one-third of patient trajectories with high completeness of lipid test and lipid-modifying drug prescription records from a pool of around 1.5 million patients under primary prevention of CVD since 2004 [34]. This massive dataset provided the necessary statistical power to learn subtle patterns in long-term treatment effectiveness.

Methodological Workflow

The following diagram illustrates Duramax's integrated learning workflow, which combines real-world data with reinforcement learning principles:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Effectiveness Against Clinical Standards

In rigorous validation against real-world clinician decisions, Duramax demonstrated superior performance in reducing long-term cardiovascular risk. The framework achieved a policy value of 93, significantly outperforming clinicians' average policy value of 68 [34]. This quantitative metric represents the expected cumulative reward from following each strategy, with higher values indicating better long-term outcomes.

When clinicians' decisions aligned with Duramax's suggestions, CVD risk reduced by 6% compared to when they deviated from the recommendations [34]. This finding is particularly significant as it demonstrates the framework's potential to augment rather than replace clinical decision-making, providing actionable insights that can improve patient outcomes.

Comparison with Traditional Treat-to-Target Approaches