Experimental vs. Observational Studies: A Researcher's Guide to Design, Application, and Evidence-Based Decision Making

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical distinction between experimental and observational studies.

Experimental vs. Observational Studies: A Researcher's Guide to Design, Application, and Evidence-Based Decision Making

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical distinction between experimental and observational studies. It covers the foundational definitions and core characteristics of each methodology, details their specific applications and design implementations, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a framework for the critical evaluation and comparison of evidence. By synthesizing these four intents, the article empowers professionals to select the most rigorous and appropriate study design for their research questions, ultimately strengthening the validity and impact of biomedical and clinical research.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Experimental and Observational Research Designs

In the rigorous world of scientific research, particularly in drug development and clinical trials, the choice of study design is foundational. The path to generating evidence—whether for a new therapeutic compound or an understanding of disease progression—is largely dictated by two primary methodological paradigms: experimental and observational studies. The former is characterized by active intervention and researcher-controlled manipulation of variables, while the latter involves passive observation of subjects in their natural state without any intervention [1] [2]. Within the context of clinical research, both designs significantly contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge, enabling scientists to develop effective new treatments and improve patient care [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches, detailing their defining protocols, applications, and the distinct types of data they yield.

Core Definitions and Methodologies

What is an Experimental Study?

An experimental study is a research design wherein an investigator deliberately manipulates one or more independent variables to establish a cause-effect relationship with a dependent variable [1]. This design is defined by the high degree of control exerted by the researcher and is often used to test specific, predictive hypotheses.

The quintessential example of an experimental study in clinical research is the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) [2]. In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to either an experimental group, which receives the new intervention (e.g., a drug), or a control group, which receives a placebo or standard treatment. This randomization minimizes selection bias and ensures that the groups are comparable, making it the gold standard for establishing the efficacy and safety of new medical interventions [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (RCT):

- Hypothesis Formulation: The researcher defines a predictive statement (e.g., "New Drug A lowers blood pressure more effectively than the current standard treatment").

- Participant Recruitment and Randomization: A sample of the target population is recruited. Participants are then randomly allocated, often using computer-generated sequences, to either the experimental or control group. This process ensures that every participant has an equal chance of being in either group, reducing the influence of confounding variables [1].

- Blinding (Masking): In a single-blind study, participants are unaware of their group assignment. In a double-blind study, neither the participants nor the researchers administering the treatment know which group is which. This prevents bias in the reporting and assessment of outcomes [2].

- Intervention and Control: The experimental group receives the intervention under investigation, while the control group receives a placebo or an established alternative.

- Data Collection and Follow-up: Data on the dependent variable(s) (e.g., blood pressure readings) are collected from both groups over a specified period.

- Data Analysis: Statistical analyses are performed to compare outcomes between the groups and determine if observed differences are statistically significant.

What is an Observational Study?

An observational study is a non-experimental research method in which the researcher merely observes subjects and measures variables of interest without interfering or manipulating any variables [1] [2]. The goal is to capture naturally occurring behaviors, conditions, or events, and the data collected often reflect real-world situations.

Observational studies are not a single entity but are categorized into specific types based on their design [2]:

- Cohort Studies: These follow a group of people (a cohort) over a period of time. They can be prospective (following participants forward in time) or retrospective (looking back at historical data). For example, a study might observe a large group of individuals without heart disease to see who develops it, comparing those who smoke and those who do not.

- Case-Control Studies: These compare a group of individuals with a specific disease or condition (the "cases") to a similar group without that condition (the "controls"). Researchers then look back to identify differences in exposure or behavior between the two groups.

- Cross-Sectional Studies: These gather data from a cross-section of the population at a single point in time, typically through surveys or interviews, to assess the prevalence of a disease or condition.

Detailed Observational Protocol (Prospective Cohort Study):

- Research Question Definition: The researcher defines a question about the relationship between an exposure and an outcome (e.g., "Does a sedentary lifestyle increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes?").

- Cohort Selection and Group Assignment: A sample is selected, often based on certain characteristics. Crucially, participants are not assigned to groups by the researcher; instead, they are grouped based on their naturally occurring exposure status (e.g., sedentary vs. active lifestyle) [2].

- Observation and Data Collection: Researchers collect data on exposures, confounders (e.g., age, diet), and outcomes over time without intervening. This is often done through medical records, surveys, or direct measurements in natural settings.

- Follow-up: The cohort is followed for a period to track the incidence of the outcome of interest.

- Data Analysis: Statistical models are used to analyze the association between the exposure and the outcome, while attempting to control for identified confounding variables.

Direct Comparison: Experimental vs. Observational Studies

The table below summarizes the key differences, strengths, and weaknesses of these two research paradigms.

| Aspect | Experimental Study | Observational Study |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | To determine cause-and-effect relationships [1] | To explore associations and correlations between variables [1] |

| Variable Manipulation | Direct manipulation of independent variables by the researcher [1] | No manipulation; variables are measured as they naturally occur [1] |

| Control & Bias | High level of control reduces confounding variables; random assignment minimizes selection bias [1] [2] | Low level of control; susceptible to confounding variables and selection bias [1] [2] |

| Establishing Causality | Able to establish causality [1] | Cannot establish causality, only correlation [1] |

| Generalizability | Sometimes limited due to controlled, artificial conditions and strict eligibility criteria (lack of ecological validity) [1] [2] | Higher ecological validity, as observations are made in real-world settings; however, findings may not apply to broader populations [1] [2] |

| Ethical Considerations | Ethical constraints exist for manipulations that could harm subjects (e.g., testing a known harmful substance) [1] [2] | Ethical method for studying harmful exposures or when manipulation is impractical (e.g., studying the effects of smoking) [2] |

| Time & Cost | Often time-consuming and costly due to need for strict controls and monitoring [1] [2] | Generally less time-consuming and costly, though long-term cohort studies can be expensive [1] |

| Primary Strengths | Establishes causality; high internal validity; results are replicable [1] [2] | Studies phenomena unethical or impractical to manipulate; high external/ecological validity [1] [2] |

| Primary Weaknesses | Potential for artificiality; ethical limitations; can be expensive [1] [2] | Cannot prove causation; prone to various biases (confounding, recall, measurement) [1] [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions used across clinical research studies, with their specific functions in both experimental and observational contexts.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Placebo | An inert substance identical in appearance to the active drug; administered to the control group in an RCT to blind participants and researchers, isolating the specific effect of the intervention from psychological effects [2]. |

| Data Collection Tools (e.g., Surveys, CRFs) | Standardized forms (Case Report Forms in trials, surveys in observational studies) used to systematically collect participant data on exposures, outcomes, and potential confounders, ensuring consistency and completeness [2] [3]. |

| Blinding Protocol | A methodological procedure (single or double-blind) where information about the intervention is concealed from participants and/or researchers to prevent bias in outcome assessment and reporting [2]. |

| Randomization Schedule | A computer-generated sequence or other formal plan used to randomly assign eligible participants to study groups, ensuring each has an equal chance of assignment to any group, thereby minimizing selection bias [1] [2]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, SAS, SPSS) | Software packages (R, Python, SPSS, SAS) used to perform descriptive and inferential statistical analyses, from calculating p-values and confidence intervals to running complex regression models [3]. |

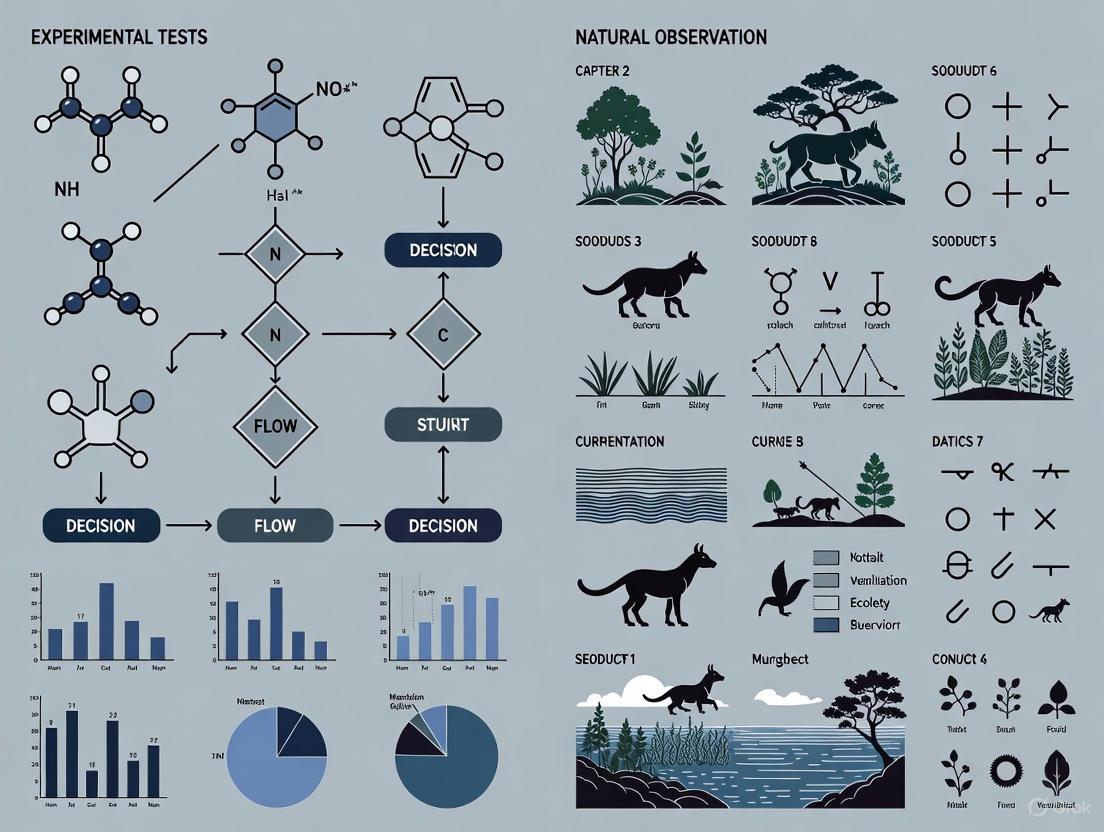

Visualizing Research Design Workflows

The logical pathways for conducting experimental and observational studies are fundamentally different. The diagrams below, created using the specified color palette, illustrate these distinct workflows.

Experimental Study Workflow (Randomized Controlled Trial)

Observational Study Workflow (Prospective Cohort)

Experimental and observational studies are complementary pillars of clinical research. The controlled, interventional nature of experimental studies like RCTs makes them the definitive method for establishing causal efficacy and bringing new drugs to market. In contrast, observational studies provide indispensable real-world evidence on long-term outcomes, effectiveness in diverse populations, and the risks and benefits of interventions as used in clinical practice. A robust research strategy understands the strengths and limitations of each paradigm, leveraging them appropriately to build a comprehensive body of evidence that ultimately advances scientific knowledge and improves patient care.

Manipulation, Control, Randomization, and Natural Setting

In scientific research, the choice between experimental tests and natural observation is fundamental, shaping the methodology, validity, and applicability of the findings. Experimental studies are characterized by active manipulation of variables and controlled conditions, whereas natural observation involves examining subjects in their native environments without intervention. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these approaches, focusing on the core characteristics of manipulation, control, randomization, and natural setting, to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate design for their investigative goals.

Core Characteristics Comparison

The table below summarizes the key differences between experimental and observational studies across the defining features of research design.

| Characteristic | Experimental Studies | Observational Studies (Natural Observation) |

|---|---|---|

| Manipulation | Active intervention by the researcher; the independent variable is manipulated. [4] | No intervention; variables are studied as they naturally occur. [4] |

| Control | High level of control over the environment and variables to isolate cause and effect. [4] | Minimal to no control; the setting is observed without alteration. [4] |

| Randomization | Random assignment of participants to control and experimental groups is a key feature. [5] [4] | Typically, no random assignment; participants are observed in pre-existing groups. [4] |

| Setting | Often conducted in controlled laboratory settings. [4] | Conducted in natural, real-world settings. [4] |

| Ability to Establish Causation | Strong, considered the "gold standard" for establishing cause-and-effect relationships. [5] [4] | Limited; can identify associations and correlations but not definitive causation. [4] |

| Susceptibility to Confounding Factors | Low, as control and randomization minimize the impact of confounding variables. [4] | High, due to the inability to control for all external factors that may influence outcomes. [4] |

| Ethical Considerations | May be unethical or impractical when manipulation could cause harm. [4] | Often preferred when it is unethical to manipulate variables or assign participants to groups. [4] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Experimental Study Protocol: Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

The RCT is the quintessential experimental design for establishing causal inference, particularly in clinical trials and drug development [5] [4].

- Objective: To determine the causal effect of a new drug (Intervention X) on blood pressure compared to a standard treatment.

- Key Methodological Steps:

- Hypothesis Formulation: State a specific, testable hypothesis (e.g., "Intervention X reduces systolic blood pressure more effectively than the standard treatment").

- Participant Recruitment and Randomization: Recruit eligible participants and use a computer-generated sequence to randomly assign them to either the intervention group (receives Intervention X) or the control group (receives the standard treatment or a placebo). This process helps ensure groups are comparable at baseline. [5] [4]

- Blinding: Implement single- (participants unaware) or double-blinding (participants and researchers unaware) to prevent bias.

- Intervention and Control: Administer the designated treatment to each group under strictly controlled and monitored conditions. [4]

- Outcome Measurement: Measure the primary outcome (e.g., change in systolic blood pressure) at predefined time points for both groups.

- Data Analysis: Compare the outcomes between the intervention and control groups using statistical tests (e.g., t-tests) to determine if observed differences are statistically significant. [4]

Observational Study Protocol: Cohort Study

Cohort studies are a primary form of natural observation that follow a group of people over time to investigate the causes of disease [5].

- Objective: To explore the association between a specific occupational exposure (e.g., prolonged exposure to Chemical A) and the incidence of a rare lung disease.

- Key Methodological Steps:

- Cohort Definition: Identify and enroll a group of workers exposed to Chemical A and a comparable group of workers not exposed. [5]

- Natural Setting Observation: Follow both cohorts over a long period (often years) in their actual work and life environments, without any intervention by the researcher. [4]

- Data Collection: Periodically collect data on health outcomes, lifestyle factors, and other relevant variables through medical records, surveys, or health screenings.

- Control for Confounding: Use statistical techniques like multiple regression analysis to account for potential confounding variables (e.g., age, smoking status) that could influence the results. [6] [4]

- Outcome Analysis: Calculate and compare the incidence rates of the lung disease between the exposed and non-exposed cohorts to determine if an association exists. [5]

Research Workflow and Causal Inference Logic

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical pathways and key decision points that differentiate experimental and observational research designs, culminating in their differing strengths for causal inference.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and methodological components essential for conducting rigorous research in both experimental and observational contexts.

| Reagent/Methodological Component | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Randomization Algorithm | A computational procedure for randomly assigning participants to study groups, which minimizes selection bias and distributes confounding factors evenly, thereby strengthening causal claims. [5] [4] |

| Control Group | A baseline group that does not receive the experimental intervention. It serves as a comparator to isolate and measure the true effect of the intervention by accounting for changes due to other factors. [4] |

| Blinding Protocol | A methodological procedure where participants (single-blind) and/or researchers and outcome assessors (double-blind) are kept unaware of group assignments to prevent conscious or unconscious bias that could influence the results. |

| Statistical Adjustment (e.g., Multiple Regression) | A suite of statistical techniques used primarily in observational studies to mathematically control for the influence of confounding variables, thereby providing a clearer picture of the relationship between the exposure and outcome of interest. [6] [4] |

| Standardized Data Collection Tool | Validated instruments such as surveys, medical imaging protocols, or laboratory assay kits that ensure consistent, reliable, and comparable measurement of variables across all participants in a study. [7] |

| Propensity Score Matching | An advanced statistical method used in quasi-experimental and observational studies to simulate randomization by matching each treated participant with one or more non-treated participants who have a similar probability (propensity) of receiving the treatment based on observed covariates. [6] |

Within the broader thesis of experimental tests versus natural observation research, the hierarchy of evidence provides a framework for ranking study designs based on their internal validity and ability to minimize bias. This guide objectively compares the two primary methodologies: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), representing experimental tests, and Observational Studies, representing natural observation.

Comparative Performance: RCTs vs. Observational Studies

The following table summarizes quantitative data comparing the performance of RCTs and Observational Studies across key metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Study Designs

| Metric | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Cohort Study | Case-Control Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Confounding Bias | Low (Theoretically 0 with perfect randomization) | Moderate to High | High |

| Ability to Establish Causality | High (Gold Standard) | Moderate | Low |

| Typical Sample Size | 100 - 10,000+ participants | 10,000 - 100,000+ participants | 500 - 5,000 participants |

| Relative Cost & Duration | High cost, Long duration | Moderate cost, Long duration | Lower cost, Shorter duration |

| Relative Risk (RR) / Odds Ratio (OR) Concordance with RCTs | Reference Standard | ~80% concordance for RR > 2 | ~70% concordance for OR > 4 |

| Ideal Use Case | Efficacy of a new drug or intervention | Long-term safety outcomes, rare exposures | Investigating rare diseases or outcomes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Parallel-Group Randomized Controlled Trial

- Protocol Development & Registration: A detailed study protocol is written, specifying objectives, design, endpoints, and statistical methods. It is registered on a public platform (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov).

- Participant Screening & Recruitment: Eligible participants are identified based on strict inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Informed Consent: All participants provide written, informed consent.

- Baseline Assessment & Randomization: Baseline data are collected. Participants are then randomly allocated to either the intervention group or the control group using a computer-generated sequence.

- Blinding (Masking): Participants, care providers, and outcome assessors are blinded to group assignment wherever possible.

- Intervention Period: The intervention group receives the investigational product (e.g., Drug A). The control group receives a placebo or standard-of-care treatment.

- Follow-up & Monitoring: Participants are followed for a predetermined period. Adherence, adverse events, and outcome data are systematically collected.

- Outcome Assessment: Primary and secondary endpoints (e.g., mortality, disease progression) are measured at the end of the study.

- Data Analysis: An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is typically performed to compare outcomes between the randomized groups.

Protocol 2: Conducting a Prospective Cohort Study

- Hypothesis Formulation: A hypothesis linking an exposure to an outcome is defined (e.g., "Does high sugar consumption lead to cardiovascular disease?").

- Cohort Assembly: A large group of participants, free of the outcome of interest, is recruited.

- Exposure Assessment: Participants are assessed and grouped based on their exposure status (e.g., high vs. low sugar diet) through questionnaires, biomarkers, or electronic health records. No intervention is applied by the researchers.

- Baseline Data Collection: Extensive data on potential confounders (e.g., age, sex, BMI, smoking status) are collected.

- Follow-up: The cohort is followed forward in time for a prolonged period (often years).

- Outcome Ascertainment: The occurrence of the outcome (e.g., heart attack) is identified through medical records, registries, or direct follow-up.

- Data Analysis: The incidence of the outcome in the exposed group is compared to the incidence in the unexposed group, calculating a Relative Risk (RR). Statistical adjustments (e.g., multivariate regression) are used to control for identified confounders.

Visualizing the Workflows and Hierarchy

Hierarchy of Evidence Pyramid

RCT Participant Workflow

Observational Study Design Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Clinical Research Studies

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Investigational Product (IP) | The drug, device, or biologic being tested for efficacy and safety. |

| Placebo | An inert substance identical in appearance to the IP, used in the control arm to blind the study. |

| Randomization System | A computerized system or service that generates an unpredictable allocation sequence to assign participants to study groups. |

| Case Report Form (CRF) | A structured document (paper or electronic) for collecting all protocol-required data for each study participant. |

| Clinical Endpoint Adjudication Committee | An independent, blinded group of experts who review and validate potential outcome events, reducing measurement bias. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Standardized reagents (e.g., ELISA, PCR) to quantitatively measure biological molecules as indicators of exposure, disease, or treatment response. |

| Electronic Data Capture (EDC) System | A secure software platform for efficient and accurate collection of clinical trial data from investigational sites. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (SAS/R) | Programming environments used for complex statistical analyses, including regression modeling and handling of missing data. |

In scientific research, particularly in fields like drug development, the integrity of a study's conclusions hinges on a precise understanding of its core components. The relationship between independent variables (the presumed cause) and dependent variables (the presumed effect) forms the bedrock of experimental inquiry [8] [9]. Furthermore, the choice of research methodology—experimental tests versus natural observation—profoundly influences the degree to which causality can be inferred from these relationships [2] [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodological approaches, detailing their protocols, strengths, and limitations to empower researchers in selecting the optimal design for their investigative goals.

An independent variable is the factor that the researcher manipulates, controls, or uses to group participants to test its effect on another variable [9]. Its value is independent of other variables in the study, making it the explanatory or predictor variable [8]. Conversely, a dependent variable is the outcome that researchers measure to see if it changes in response to the independent variable [9]. It "depends" on the independent variable and represents the effect or response in the cause-and-effect relationship being studied [8] [10]. Confounding variables are a critical third factor that can distort this relationship. These are extraneous variables that influence both the independent and dependent variables, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about causality [11] [12].

Experimental Research vs. Natural Observation: A Comparative Analysis

The core distinction in research design lies in the researcher's level of control and intervention. The following table provides a structured comparison of these two primary approaches, summarizing their key characteristics, data presentation styles, and inherent challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Experimental and Observational Research Designs

| Aspect | Experimental Research | Observational Research (Natural Observation) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | A research method where the investigator actively manipulates one or more independent variables to establish a cause-and-effect relationship [2] [1]. | A non-experimental research method where the investigator observes subjects and measures variables without any interference or manipulation [2] [4]. |

| Researcher Control | High degree of control over the environment, variables, and participant assignment [1] [4]. | Minimal to no control; researchers observe variables as they naturally occur [2] [1]. |

| Primary Objective | To test specific hypotheses and definitively establish causation [1] [4]. | To identify patterns, correlations, and associations in real-world settings [2] [4]. |

| Ability to Establish Causality | High; the gold standard for inferring cause-and-effect due to manipulation and control of confounding factors [2] [1]. | Low; cannot establish causation, only correlation, due to the presence of uncontrolled confounding variables [1] [4]. |

| Key Methodological Features | - Manipulation of the independent variable- Random assignment of participants- Use of control groups [2] [1] | - No manipulation of variables- Observation in natural settings- Groups based on pre-existing characteristics [2] [4] |

| Data Presentation | Data is often presented to show differences between experimental and control groups, using measures like means and standard deviations. T-tests and ANOVAs are common analytical tests [8] [9]. | Data often shows associations between variables, presented as correlation coefficients or risk ratios. Regression analysis is frequently used to control for known confounders [11] [4]. |

| Common Challenges | - Can lack ecological validity (real-world applicability)- Ethical constraints on manipulations- Can be costly and time-consuming [2] [1] | - Highly susceptible to confounding variables- Potential for selection and observer bias- Cannot determine causality [2] [11] |

| Ideal Use Cases | - Establishing the efficacy of a new drug [2]- Testing a specific psychological intervention [9]- Studying short-term effects under controlled conditions [4] | - Studying long-term effects or rare events [2] [4]- When manipulation is unethical (e.g., smoking studies) [2] [1]- Large-scale population-based research [4] |

Visualizing Research Design and Confounding Variables

The logical flow of a research design and the insidious role of confounding variables can be effectively communicated through diagrams. The following workflows are generated using Graphviz DOT language, adhering to the specified color palette and contrast rules.

Experimental Research Workflow

The diagram below outlines the standard protocol for a true experimental design, such as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), which is central to establishing causality.

The Problem of Confounding Variables

This diagram illustrates how a confounding variable can create a false impression of a direct cause-and-effect relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

The RCT is the quintessential experimental design for establishing causality, especially in drug development [2]. The following protocol outlines its key phases.

Phase 1: Study Design and Preparation

- Hypothesis Formulation: Clearly state the predicted causal relationship. For example: "If patients with Condition X receive Drug Y (IV), then they will experience a greater reduction in Symptom Z (DV) compared to those receiving a placebo."

- Operationalization: Precisely define how the IV will be manipulated and the DV will be measured [9]. For instance, the IV is "10mg of Drug Y daily," and the DV is "the score on the Standardized Symptom Z Scale after 8 weeks."

- Participant Recruitment: Identify the target population using specific inclusion and exclusion criteria [2].

- Randomization: Use a computer-generated sequence to randomly assign eligible participants to either the experimental or control group. This is critical for minimizing selection bias and distributing known and unknown confounding variables evenly across groups [2] [1].

Phase 2: Intervention and Blinding

- Intervention: Administer the active drug to the experimental group and a matched placebo to the control group. All other conditions (e.g., clinic visits, dietary advice) are kept identical between groups [2].

- Blinding: Implement a double-blind procedure where neither the participants nor the researchers directly assessing the outcomes know which group a participant is in. This prevents bias in the reporting and measurement of the DV [2].

Phase 3: Data Collection and Analysis

- Measurement: Measure the DV in both groups at the end of the intervention period (and potentially at baseline and interim points) using the pre-specified tool [8].

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the average DV scores between the experimental and control groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA) to determine if the difference is statistically significant [8] [4]. Advanced techniques like regression analysis may be used to control for any residual confounding [11].

Protocol for a Cohort Observational Study

A cohort study is a common type of observational design used to investigate the potential effects of an exposure in a naturalistic setting [2].

Phase 1: Study Design and Cohort Selection

- Research Question: Formulate a question about association, not causation. For example: "Is there an association between prolonged exposure to Substance A (IV) and the incidence of Disease B (DV)?"

- Cohort Assembly: Identify a large group of participants who are free of Disease B at the start of the study. Within this group, classify participants based on their pre-existing exposure to Substance A (the IV). This is a subject variable, as the researcher does not assign the exposure [8] [13].

- Matching: To control for key confounding variables (e.g., age, gender), researchers may "match" each exposed individual with one or more unexposed individuals who share similar characteristics [11].

Phase 2: Long-Term Follow-Up

Phase 3: Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Comparison: Calculate and compare the incidence rates of Disease B between the exposed and unexposed cohorts.

- Statistical Control: Use multivariate statistical models (e.g., regression analysis) to adjust for the influence of measured confounding variables (e.g., smoking status, diet) on the relationship between the IV and DV [11]. It is crucial to note that despite these adjustments, the study can only demonstrate correlation, as unmeasured or unknown confounders may still influence the results [2] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting rigorous experimental research, particularly in biomedical and pharmacological contexts.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Experimental Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | The central independent variable in drug trials; the substance whose causal effect on a biological system or disease is being tested [2] [13]. |

| Placebo | An inert substance identical in appearance to the API. Serves as the control condition for the experimental group, allowing researchers to isolate the specific pharmacological effect of the API from psychological or placebo effects [2]. |

| Buffers and Solvents | Stable, biologically compatible solutions used to dissolve or dilute the API and placebo, ensuring accurate dosing and administration to experimental groups [2]. |

| Assay Kits | Pre-packaged reagents used to quantitatively measure the dependent variable(s), such as biomarker levels, enzyme activity, or cell viability, ensuring standardized and reliable outcome measurement [14]. |

| Cell Culture Media | A precisely formulated solution that provides essential nutrients to support the growth and maintenance of cell lines in in vitro studies, providing a controlled environment for testing the IV [2]. |

| Blocking Agents & Antibodies | Reagents used in immunoassays and histochemistry to reduce non-specific binding (blocking) and specifically detect target molecules (antibodies), enabling precise measurement of biological DVs [14]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Robust Study Designs in Biomedical Research

Within the broader thesis on experimental tests versus natural observation research, observational studies represent a cornerstone of scientific inquiry in situations where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are impractical, unethical, or impossible to conduct [15] [16]. While experimental studies actively intervene by assigning treatments to establish causality, observational studies take a more naturalistic approach by measuring exposures and outcomes as they occur in real-world settings without researcher intervention [17] [18]. This fundamental distinction positions observational research as the only practicable method for answering critical questions of aetiology, natural history of rare conditions, and instances where an RCT might be unethical [15] [19].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the precise applications, strengths, and limitations of different observational designs is crucial for both conducting and critically appraising scientific evidence. Three primary types of observational studies form the backbone of this methodological approach: cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies [20] [16] [21]. Each serves distinct research purposes and offers unique advantages for investigating relationships between exposures and outcomes in population-based research. These designs are collectively classified as level II or III evidence in the evidence-based medicine hierarchy, yet well-designed observational studies have been shown to provide results comparable to RCTs, challenging the notion that they are inherently second-rate [16].

Comparative Analysis of Observational Study Designs

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the three main observational study designs, highlighting their key characteristics, applications, and methodological considerations.

| Feature | Cohort Study | Case-Control Study | Cross-Sectional Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Objective | Study incidence, causes, and prognosis [15] | Identify predictors of outcome and study rare diseases [15] | Determine prevalence [15] |

| Temporal Direction | Prospective or retrospective [16] | Retrospective [15] | Single point in time [16] |

| Direction of Inquiry | Exposure → Outcome [16] | Outcome → Exposure [16] | Exposure & Outcome simultaneously [16] |

| Incidence Calculation | Can calculate incidence and relative risk [16] | Cannot calculate incidence [16] | Cannot calculate incidence [16] |

| Time Requirement | Long follow-up (prospective); shorter (retrospective) [22] | Relatively quick [22] | Quick and easy [15] |

| Cost Factor | Expensive (prospective); less costly (retrospective) [16] | Inexpensive [22] | Inexpensive [17] |

| Sample Size | Large sample size often needed [16] | Fewer subjects needed [17] | Variable, often large [17] |

| Ability to Establish Causality | Can suggest causality due to temporal sequence [15] | Cannot establish causality [15] | Cannot establish causality [15] |

| Key Advantage | Can examine multiple outcomes for a single exposure [16] | Efficient for rare diseases or outcomes with long latency [15] [16] | Provides a snapshot of population characteristics [22] |

| Primary Limitation | Susceptible to loss to follow-up (prospective) [16] | Vulnerable to recall and selection biases [16] [17] | Cannot distinguish cause and effect [15] |

Workflow and Temporal Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental temporal structures and participant flow characteristics that differentiate the three main observational study designs.

Detailed Examination of Study Designs

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies involve identifying a group (cohort) of individuals with specific characteristics in common and following them over time to gather data about exposure to factors and the development of outcomes of interest [23]. The term "cohort" originates from the Latin word cohors, referring to a Roman military unit, and in modern epidemiology defines "a group of people with defined characteristics who are followed up to determine incidence of, or mortality from, some specific disease, all causes of death, or some other outcome" [16].

Experimental Protocol for Prospective Cohort Studies:

- Population Definition: Identify and select a study population free of the outcome of interest at baseline [16]

- Exposure Assessment: Measure and document exposure status (exposed vs. unexposed) at the start of the investigation [16]

- Follow-up Period: Establish a predetermined follow-up duration with regular intervals for data collection [18]

- Outcome Measurement: Systematically measure and document outcome occurrence in both exposed and unexposed groups [16]

- Data Analysis: Compare incidence rates between groups to calculate relative risk and other measures of association [16]

Cohort studies can be conducted prospectively (forward-looking) or retrospectively (backward-looking) [16] [18]. Prospective designs, such as the landmark Framingham Heart Study, follow participants from the present into the future, allowing tailored data collection but requiring long follow-up periods [16]. Retrospective cohort studies use existing data to look back at exposure and outcome relationships, making them less costly and time-consuming but vulnerable to data quality issues [16]. A key methodological concern in prospective cohort studies is attrition bias, with a general rule suggesting loss to follow-up should not exceed 20% of the sample to maintain internal validity [16].

Case-Control Studies

Case-control studies work by identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and matching them with individuals who have similar characteristics but do not have the outcome (controls), then looking back to see if these groups differed regarding the exposure of interest [23]. This design is particularly valuable for studying rare diseases or outcomes with long latency periods where cohort studies would be inefficient [15] [16].

Experimental Protocol for Case-Control Studies:

- Case Definition: Establish clear diagnostic and eligibility criteria for case selection [16]

- Control Selection: Identify appropriate controls from the same source population as cases, matching for potential confounders like age and gender [20] [16]

- Exposure Assessment: Gather historical exposure data through interviews, medical records, or other sources for both groups [18]

- Blinding: Ensure researchers assessing exposure status are blinded to case/control status to minimize bias [16]

- Data Analysis: Calculate odds ratios to estimate the strength of association between exposure and outcome [16]

The case-control design is inherently retrospective, moving from outcome to exposure [16]. A major methodological challenge is the appropriate selection of controls, who should represent the source population that gave rise to the cases [16]. These studies are particularly vulnerable to recall bias, as participants with the outcome may remember exposures differently than controls, and confounding variables may unequally distribute between groups [17].

Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies examine the relationship between diseases and other variables as they exist in a defined population at one particular time, measuring both exposure and outcomes simultaneously [17]. These studies are essentially a "snapshot" of a population at a specific point in time [21].

Experimental Protocol for Cross-Sectional Studies:

- Population Sampling: Select a representative sample from the target population, often using random sampling methods [17]

- Single Time Point Assessment: Administer all measurements, interviews, or examinations at the same point in time [21]

- Data Collection: Gather information on both exposure/factor status and outcome/disease status concurrently [16]

- Prevalence Calculation: Determine disease prevalence and exposure prevalence within the sample [15]

- Association Analysis: Examine relationships between exposures and outcomes using statistical tests for association [17]

Because cross-sectional studies measure exposure and outcome simultaneously, they cannot establish temporality or distinguish whether the exposure preceded or resulted from the outcome [15] [16]. This fundamental limitation means they can establish association at most, not causality [17]. However, they are valuable for determining disease prevalence, assessing public health needs, and generating hypotheses for more rigorous studies [15] [20]. They are also susceptible to the "Neyman bias," a form of selection bias that can occur when the duration of illness affects the likelihood of being included in the study [17].

Research Reagent Solutions: Methodological Tools for Observational Research

The table below outlines essential methodological components and tools for conducting rigorous observational research, analogous to research reagents in laboratory science.

| Methodological Component | Function & Application | Study Design Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Questionnaires | Ensure consistent, comparable data collection across all participants [22] | All observational designs, particularly cross-sectional studies [22] |

| Electronic Health Records (EHR) | Provide existing longitudinal data for retrospective analyses [16] | Retrospective cohort and case-control studies [16] |

| Matching Protocols | Minimize confounding by ensuring cases and controls are similar in key characteristics [20] [16] | Primarily case-control studies [16] |

| Follow-up Tracking Systems | Maintain participant contact and minimize loss to follow-up [16] | Prospective cohort studies [16] |

| Blinded Outcome Adjudication | Reduce measurement bias by concealing exposure status from outcome assessors [16] | Primarily cohort studies [16] |

| Statistical Analysis Plans | Pre-specified protocols for calculating measures of association and addressing confounding [16] [17] | All analytical observational designs [17] |

Decision Framework for Study Design Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to selecting the most appropriate observational study design based on specific research questions and practical considerations.

Cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies collectively form an essential methodological toolkit for investigating research questions where randomized controlled trials are not feasible, ethical, or practical [15] [19]. Each design offers distinct advantages: cohort studies for establishing incidence and temporal relationships, case-control studies for efficient investigation of rare conditions, and cross-sectional studies for determining prevalence and generating hypotheses [15] [16]. The choice between these designs depends fundamentally on the research question, frequency of the outcome, available resources and time, and the specific information needs regarding disease causation or progression [18].

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise applications, strengths, and limitations of each observational design is crucial for both conducting rigorous studies and critically evaluating published literature. While observational studies cannot establish causality with the same reliability as well-designed RCTs, they provide invaluable evidence for understanding disease patterns, risk factors, and natural history [16] [18]. When designed and implemented with careful attention to minimizing bias and confounding, observational studies make indispensable contributions to evidence-based medicine and public health decision-making.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are universally regarded as the gold standard for clinical research, providing the foundation for evidence-based medicine. Their design is uniquely capable of establishing causal inference between an intervention and an outcome, primarily through the use of randomization to minimize confounding bias. This guide explores the implementation of traditional RCTs, their core variations, and how they compare to observational studies within the broader landscape of clinical evidence generation.

The Core Principles and Regulatory Backbone of RCTs

An RCT is a true experiment in which participants are randomly allocated to receive either a specific intervention (the experimental group) or a different intervention (the control or comparison group). The scientific design hinges on two key components [24]:

- Randomized: Researchers decide randomly which participants receive the new treatment and which receive a placebo or reference treatment. This eliminates selection bias, preventing the deliberate or unconscious skewing of results by ensuring that known and unknown prognostic factors are balanced across groups. [25] [26] [24]

- Controlled: The trial uses a control group for comparison. This group may receive a placebo, an established standard of care, or no treatment. The control group is essential for determining whether observed effects can be genuinely attributed to the experimental intervention, as it accounts for other factors that could influence the outcome. [24]

Regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) generally require evidence from RCTs to approve new drugs and high-risk medical devices [27] [24]. This is because RCTs' internal validity offers the best assessment of a treatment's efficacy—whether it works under ideal and controlled conditions [28].

Variations on the Gold Standard: Adaptive and Streamlined Trial Designs

While the classic two-arm, parallel-group RCT is foundational, several innovative variations have been developed to enhance efficiency, ethics, and applicability.

Table 1: Key Variations of Randomized Controlled Trials

| Variation Type | Primary Objective | Key Features | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Trials [26] | To create more flexible and efficient trials. | Pre-planned interim analyses allow for modifications (e.g., dropping ineffective arms, adjusting sample size) without compromising validity. | Evaluating multiple potential therapies for a new disease. |

| Platform Trials [26] [27] | To study an entire disease domain with a sustainable infrastructure. | Multiple interventions are compared against a common control arm. Interventions can be added or dropped over time based on performance. | The RECOVERY trial for COVID-19 treatments. [27] |

| Large Simple Trials [27] | To answer pragmatic clinical questions with high generalizability. | Streamlined design, minimal data collection, and use of routinely collected healthcare data (e.g., electronic health records, registries) to enroll large, representative populations quickly and cost-effectively. | The TASTE trial assessing a medical device for heart attack patients. [27] |

| Single-Arm Trials with External Controls [29] [30] | To provide evidence when a concurrent control group is unethical or infeasible. | All participants receive the experimental therapy. Their outcomes are compared to an externally sourced control group, often built from historical data like natural history studies or patient registries. | Trials for rare diseases, such as the approval of Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy. [30] |

Methodological Protocols: From Traditional to Modern RCTs

Protocol 1: The Traditional Two-Arm RCT

This is the foundational design for establishing efficacy [31].

- Protocol Development: A prospective study protocol is created with strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, a well-defined intervention, and pre-specified primary and secondary endpoints. [28]

- Randomization & Blinding: Eligible participants are randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. Allocation concealment and blinding (single, double, or triple) are used to prevent bias. [31]

- Intervention & Follow-up: The assigned intervention is administered per protocol, and participants are followed for a pre-determined period.

- Outcome Assessment: Endpoints are measured and compared between the two groups. The primary analysis is typically conducted on an intention-to-treat basis.

Protocol 2: Large Simple RCT Using Real-World Data

This pragmatic design assesses effectiveness—how a treatment performs in real-world clinical practice [27].

- Streamlined Setup: Eligibility criteria are broad and inclusive to reflect a typical patient population. The trial is often embedded within healthcare systems.

- Minimal Site Workload: A one-page electronic case report form (eCRF) is used at key points (e.g., randomization, discharge/death). This was successfully implemented in the RECOVERY trial. [27]

- Routine Data Linkage: Follow-up data for key outcomes (e.g., all-cause mortality) are automatically supplemented through linkages to national healthcare databases, claims data, or disease registries, ensuring complete follow-up with minimal extra effort. [27]

- Analysis: The analysis focuses on a few important clinical outcomes collected from the linked databases.

Experimental vs. Control Group Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Clinical Trials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Clinical Trials

| Item / Solution | Function in the Clinical Trial |

|---|---|

| Investigational Product | The drug, biologic, or device being tested. Its purity, potency, and stability are critical and must be manufactured under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). |

| Placebo | An inert substance or dummy device that is indistinguishable from the active product. It serves as the control to isolate the psychological and incidental effects from the true pharmacological effect of the intervention. [24] |

| Randomization System | A computerized or web-based system (e.g., Interactive Web Response System - IWRS) that ensures the unbiased allocation of participants to study arms, maintaining allocation concealment. |

| Electronic Data Capture (EDC) | A software system for collecting clinical data electronically. It streamlines data management, improves quality, and is essential for large simple trials using case report forms. [27] |

| Standard of Care Treatment | An established, effective treatment used as an active comparator in the control arm. This allows for a direct comparison of the new intervention's benefit against the current best practice. [24] |

| Protocol | The master plan for the entire trial. It details the study's objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and organization, ensuring consistency and scientific rigor across all trial sites. [28] |

RCTs vs. Observational Studies: An Objective Data-Driven Comparison

The choice between an RCT and an observational study is dictated by the research question, with each playing a distinct role in the evidence ecosystem. RCTs are optimal for establishing efficacy under controlled conditions, while well-designed observational studies are invaluable for assessing effectiveness in real-world settings, long-term safety, and when RCTs are unethical or impractical [32] [26] [28].

A 2021 systematic review of 30 systematic reviews across 7 therapeutic areas provided a direct quantitative comparison, analyzing 74 pairs of pooled relative effect estimates from RCTs and observational studies [32]. The key findings are summarized below:

RCT vs. Observational Study Comparison

This data shows that while the majority of comparisons show no significant difference, a substantial proportion exhibit extreme variation, underscoring the potential for bias in observational estimates and the complementary roles of both designs [32].

Observational studies are particularly crucial in rare disease drug development, where patient populations are small and traditional RCTs may be infeasible. Regulatory approvals for drugs like Skyclarys (omaveloxolone) for Friedreich's ataxia and Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy have leveraged natural history studies as external controls in single-arm trials [29] [30].

Within the broader thesis on experimental tests versus natural observation research, the fundamental choice of methodology is dictated by the research question itself. This decision determines the quality of the evidence, the strength of the conclusions, and the very applicability of the findings to real-world scenarios. Experimental studies are characterized by the deliberate manipulation of variables under controlled conditions to establish cause-and-effect relationships [1] [33]. In contrast, observational studies involve measuring variables as they naturally occur, without any intervention from the researcher [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodological pillars, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the criteria necessary to select the optimal design for their investigative goals.

Core Definitions and Methodological Frameworks

What is an Experimental Study?

An experimental study is a research design in which an investigator actively manipulates one or more independent variables to observe their effect on a dependent variable, typically with the goal of establishing a cause-effect relationship [1] [4]. The hallmarks of this approach include a high degree of control over the environment, and the random assignment of participants to different groups, such as an experimental group that receives the intervention and a control group that does not [1] [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: The Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

The RCT is considered the gold standard for experimental research in fields like medicine and pharmacology [5] [2]. The workflow can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 1: Experimental RCT Workflow.

Key aspects of this protocol include:

- Blinding: In single- or double-blind designs, participants and/or researchers are unaware of group assignments to prevent bias [2] [33].

- Control: Strict protocols ensure the environment and procedures are consistent for all groups, isolating the effect of the independent variable [1] [33].

What is an Observational Study?

An observational study is a non-experimental research method where the investigator observes subjects and measures variables of interest without assigning treatments or interfering with the natural course of events [1] [4]. The researcher's role is to document, rather than influence, what is occurring. These studies are primarily used to identify patterns, correlations, and associations in real-world settings [2].

Detailed Observational Protocol: The Cohort Study

A common and powerful observational design is the cohort study, which follows a group of people over time [5] [2]. The workflow is fundamentally different from an experiment:

Diagram 2: Observational Cohort Study Workflow.

Key aspects of this protocol include:

- No Manipulation: The researcher does not assign exposures (e.g., smoking, a specific diet); they merely record the existing exposures of the participants [1] [34].

- Natural Setting: Data collection occurs in the subject's environment, such as a clinic, workplace, or home, which provides high ecological validity [35] [36].

Objective Comparison: Experimental vs. Observational Studies

The following tables provide a structured, quantitative and qualitative comparison of the two methodologies, highlighting their distinct characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Methodological Rigor

| Aspect | Experimental Study | Observational Study |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Manipulation | Active manipulation of independent variable(s) [1] [33] | No manipulation; observes variables as they occur [1] [33] |

| Control Over Environment | High control; often in lab settings [1] [33] | Little to no control; natural, real-world settings [1] [33] |

| Random Assignment | Yes, participants are randomly assigned to groups [1] [5] | No random assignment; groups are pre-existing [4] |

| Ability to Establish Causation | High; can establish cause-and-effect [1] [2] | Low; can only identify correlations/associations [1] [5] |

| Use of Control Group | Yes, to compare against experimental group [1] [4] | Sometimes (e.g., in case-control studies), but not through assignment [5] |

| Key Research Output | Evidence of causal effect from intervention [2] | Evidence of a relationship or pattern between variables [2] |

Table 2: Practical Considerations, Validity, and Application

| Aspect | Experimental Study | Observational Study |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Validity | Potentially low due to artificial, controlled setting [1] | High, as data is captured in real-world environments [1] [35] |

| Susceptibility to Bias | Risk of demand characteristics/experimenter bias [1] | Risk of observer, selection, and confounding bias [1] [5] |

| Ethical Considerations | Can be constrained; manipulation may be unethical [1] [4] | More ethical when manipulation is unsafe or unethical [2] [4] |

| Time & Cost | Often more time-consuming and costly [1] [5] | Generally less costly and faster to implement [1] [33] |

| Replicability | High, due to controlled conditions [1] | Low to medium, as natural conditions are hard to recreate [1] |

| Ideal Use Case | Testing hypotheses, particularly cause and effect [1] | Exploring phenomena in real-world contexts [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and solutions central to conducting rigorous experimental research, particularly in drug development.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Experimental Research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Placebo | An inactive substance identical in appearance to the active drug, used in the control group to blind participants and researchers, isolating the pharmacological effect from the placebo effect [2]. |

| Active Comparator/Standard of Care | An established, effective treatment used in the control group to benchmark the performance and efficacy of a new experimental intervention [2]. |

| Blinding/Masking Protocols | Procedures (single- or double-blind) that ensure participants and/or investigators are unaware of treatment assignments to minimize bias in outcome assessment [2] [33]. |

| Randomization Schedule | A computer-generated or statistical plan that ensures each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any study group, minimizing selection bias and balancing confounding factors [1] [5]. |

| Validated Measurement Instruments | Tools and assays (e.g., ELISA kits, PCR assays, clinical rating scales) that have been confirmed to accurately and reliably measure the dependent variables of interest [1]. |

The choice between an experimental and observational design is not a matter of which is superior, but of which is most appropriate for the research question at hand [1] [4].

Choose an experimental study when your objective is to establish causation, test a specific hypothesis about the effect of an intervention, and when it is ethically and practically feasible to manipulate variables and control the environment [33] [4]. This is the preferred methodology for definitive efficacy testing of new drugs and therapies [2].

Choose an observational study when your objective is to understand patterns, prevalence, and associations in a naturalistic context, when it would be unethical to manipulate the independent variable (e.g., studying the effects of smoking), or when studying long-term outcomes or rare events that are not feasible to replicate in a lab [2] [4]. This methodology is ideal for generating hypotheses, studying real-world effectiveness, and analyzing risk factors.

By systematically applying this framework and understanding the core protocols, comparisons, and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed, strategic decisions that enhance the validity, impact, and applicability of their scientific work.

In drug development and clinical research, the choice between experimental tests and natural observation is fundamental, shaping the evidence generated and the decisions that follow. Experimental studies, characterized by active researcher intervention and variable manipulation, establish cause-and-effect relationships, making them the gold standard for demonstrating therapeutic efficacy. In contrast, observational studies gather data on subjects in their natural settings without intervention, providing critical real-world evidence on disease progression and treatment effectiveness in routine clinical practice [2] [37]. This guide objectively compares these methodologies through real-world case studies, detailing their protocols, applications, and performance in generating reliable evidence for the scientific community.

The distinction between these approaches is profound. Experimental designs, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs), exert high control, using randomization and blinding to minimize bias and confidently establish causality between an intervention and an outcome [2] [1]. Observational designs, such as cohort studies and case-control studies, forego such manipulation, instead seeking to understand relationships and outcomes as they unfold naturally in heterogeneous patient populations [2]. Each method contributes uniquely to the medical evidence ecosystem, and their comparative strengths and limitations are best illustrated through direct application in drug development.

Methodological Framework: Core Concepts and Definitions

Experimental Studies

An experimental study is defined by the active manipulation of one or more independent variables (e.g., a drug treatment) by the investigator to observe the effect on a dependent variable (e.g., disease symptoms) [2] [1]. The core objective is to establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

- Key Characteristics: Manipulation of variables, controlled environment, use of randomization and blinding, and the presence of a control group for comparison [37] [1].

- Primary Goal: To test specific hypotheses about the efficacy and safety of medical interventions.

- Common Designs: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), crossover trials, and pragmatic trials [2].

Observational Studies

An observational study involves researchers collecting data without interfering or manipulating any variables [2] [35]. The goal is to understand phenomena and identify associations as they exist in real-world settings.

- Key Characteristics: No intervention, data collection in natural environments, and subjects are not assigned to specific treatments by the researcher [37].

- Primary Goal: To describe patterns, identify risk factors, and generate hypotheses, particularly when experiments are impractical or unethical.

- Common Designs: Cohort studies (prospective or retrospective), case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies [2].

The following workflow visualizes the fundamental decision-making process and structure of these two methodological approaches in clinical research.

Experimental Study Case Study: The Randomized Controlled Vaccine Trial

Experimental Protocol and Design

Vaccine trials represent a quintessential application of the experimental model, designed to provide definitive evidence of efficacy and safety [37].

- Hypothesis: A pre-specified, testable hypothesis is formulated, e.g., "The investigational vaccine reduces the incidence of disease X compared to a placebo."

- Randomization: Participants meeting strict inclusion/exclusion criteria are randomly assigned to either the investigational vaccine group or the control group (which receives a placebo or standard-of-care vaccine) [2] [1]. This minimizes selection bias and ensures groups are comparable at baseline.

- Blinding: The study is typically double-blinded, meaning neither the participants nor the investigators know who is receiving the vaccine or the placebo. This prevents bias in outcome assessment and reporting [2].

- Control Group: The use of a placebo control group is critical to isolate the specific effect of the vaccine from other factors and to account for the placebo effect [2].

- Data Collection: Participants are followed for a predetermined period to monitor for disease incidence (the primary efficacy outcome) and the occurrence of any adverse events (safety outcomes).

Performance and Outcomes

The experimental vaccine trial design delivers high-quality evidence for regulatory decision-making.

- Causal Inference: The combination of randomization, blinding, and a control group allows researchers to conclude that observed differences in disease incidence are causally related to the vaccine [2] [1].

- Minimized Bias: Blinding procedures significantly reduce the risk of performance and detection bias.

- Regulatory Approval: This rigorous design generates the evidence required by agencies like the FDA and EMA for approving new drugs and vaccines [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes from a Hypothetical Vaccine RCT

| Study Arm | Sample Size | Disease Incidence | Relative Risk Reduction | Common Adverse Event Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Group | 15,000 | 0.1% | 95% | 15% |

| Placebo Group | 15,000 | 2.0% | - | 14% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for an RCT

Table 2: Essential Materials for a Clinical Trial

| Item/Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Investigational Product | The vaccine or drug whose safety and efficacy are being tested. |

| Placebo | An inert substance identical in appearance to the investigational product, used to blind the study and control for the placebo effect. |

| Randomization System | A computerized system to ensure each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any study group, minimizing allocation bias. |

| Case Report Form (eCRF) | A standardized tool (increasingly electronic) for collecting accurate and comprehensive data from each participant throughout the trial. |

| Laboratory Kits | Standardized kits for processing and analyzing biological samples (e.g., serology for antibody titers). |

Observational Study Case Study: Naturalistic Research on Smoking and Lung Cancer

Observational Protocol and Design

The definitive link between smoking and lung cancer was established through large-scale, long-term observational cohort studies, as it would be unethical to randomly assign people to smoke [2] [37] [35].

- Study Design: Prospective Cohort Study. A large group of individuals who did not have cancer were enrolled and their smoking behaviors were assessed.

- Participant Selection: A sample was selected, often based on exposure (smokers and non-smokers), but without any intervention from the researchers [2].

- Data Collection: Researchers followed the cohort over many years (often decades), collecting data on who developed lung cancer and who did not. This is a key feature of cohort studies: following groups over time [2].

- Comparison: The incidence rate of lung cancer in the group of smokers was compared to the incidence rate in the group of non-smokers.

Performance and Outcomes

This naturalistic observation approach provides powerful real-world evidence but has inherent limitations.

- Real-World Insights: The study captured data in a natural environment, making the findings highly applicable to the general population (high external validity) [2] [35].

- Ethical Advantage: It allowed for the study of a harmful exposure without ethically imposing it on subjects [2].

- Identification of Association: The study identified a strong association between smoking and lung cancer, which was consistent across multiple studies, suggesting causality.

- Challenges: The study was susceptible to confounding variables (e.g., diet, occupational exposure to carcinogens) that could also influence lung cancer risk. While statistical methods can adjust for known confounders, residual confounding remains a limitation [2].

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes from a Hypothetical Observational Cohort Study

| Cohort | Sample Size | Person-Years of Follow-up | Lung Cancer Cases | Incidence Rate per 10,000 PY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers | 20,000 | 380,000 | 1,140 | 30.0 |

| Non-Smokers | 30,000 | 570,000 | 171 | 3.0 |

Comparative Analysis: Performance Data and Application Context

The following table provides a structured, side-by-side comparison of the two methodologies, summarizing their performance across key metrics relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Table 4: Direct Comparison of Experimental vs. Observational Study Designs

| Criteria | Experimental Study (e.g., RCT) | Observational Study (e.g., Cohort) |

|---|---|---|

| Researcher Control | Active manipulation of variables [37] | No manipulation; observation only [37] |

| Causality Establishment | Directly measured; can prove cause-and-effect [37] [1] | Limited or inferred; can only show association [37] [1] |

| Use of Randomization | Commonly used to minimize bias [2] | Not used; participants self-select or are selected based on exposure [2] |

| Internal Validity | High (controlled environment minimizes bias) [1] | Lower (susceptible to confounding and bias) [2] |

| External Validity / Generalizability | Sometimes limited due to strict inclusion criteria [2] [1] | Generally higher, as data comes from real-world settings [2] [1] |

| Ethical Considerations | Can be high (withholding treatment, potential side effects) [2] | Generally lower, as it studies natural courses [2] [37] |

| Primary Application in Drug Development | Regulatory approval; establishing efficacy and safety [2] | Post-marketing surveillance; long-term outcomes; comparative effectiveness [2] [38] |

| Resource Requirements | Higher due to controlled setup, monitoring, and interventions [2] [37] | Generally lower cost, though long-term follow-up can be expensive [37] [1] |

| Flexibility | Fixed, rigid protocol with limited flexibility after initiation [2] | More flexible design that can evolve during the study [35] |

Integrated Applications: Functional Service Providers in Modern Clinical Research

The execution of both experimental and observational studies in today's complex environment often involves specialized partners. Functional Service Providers (FSPs) have emerged as strategic partners for pharmaceutical sponsors, offering specialized services in specific functional areas like clinical monitoring, data management, biostatistics, and pharmacovigilance [39].

This model allows sponsors to access top-tier expertise and scalable resources, enhancing the quality and efficiency of research, whether it is a tightly controlled RCT or a large observational real-world evidence study [39]. Leading FSPs like IQVIA, Parexel, and ICON provide the operational excellence and analytical rigor required to manage the intricacies of modern clinical trials and the vast datasets generated by observational research [39] [40]. The trend toward leveraging such specialized partners underscores the growing sophistication and collaborative nature of drug development, where methodological purity is supported by optimized operational execution.

The dichotomy between experimental tests and natural observation is not a contest for superiority but a recognition of complementary roles in building robust medical evidence. As demonstrated through the vaccine trial and smoking study case studies, randomized controlled trials provide the rigorous, controlled environment necessary for establishing causal efficacy, forming the bedrock of regulatory approval. Conversely, observational studies offer indispensable insights into the long-term, real-world effectiveness and safety of interventions across diverse populations, guiding clinical practice and health policy.

A sophisticated drug development strategy intentionally leverages both. It uses experimental methods to confirm a drug's biological effect and then employs naturalistic observation to understand its full impact in the complex ecosystem of routine patient care. Together, these methodologies form a complete evidence generation cycle, driving innovation and improving patient outcomes.

Navigating Research Pitfalls: Strategies to Mitigate Bias and Enhance Study Validity

Observational studies are a cornerstone of research in fields such as epidemiology, sociology, and comparative effectiveness research, where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not always feasible or ethical [5]. Unlike experimental studies, where researchers assign interventions, observational studies involve classifying individuals as exposed or non-exposed to certain risk factors and observing outcomes without any intervention [41] [42]. This fundamental difference, while allowing for the investigation of important questions, introduces significant methodological challenges that can compromise the validity of the findings.

The two most pervasive threats to the validity of observational studies are confounding and selection bias [43] [44]. Confounding can create illusory associations or mask real ones, while selection bias can render a study population non-representative, leading to erroneous conclusions [45] [46]. Understanding, identifying, and mitigating these biases is paramount for researchers who rely on observational data to guide future research or inform clinical and policy decisions. This guide explores these challenges within the broader context of comparing the robustness of experimental tests versus natural observation research, providing a detailed overview of strategies to enhance the reliability of observational study findings.

Understanding Confounding

Definition and Core Principles

Confounding derives from the Latin confundere, meaning "to mix" [41]. It is a situation in which a non-causal association between an exposure and an outcome is observed because of a third variable, known as a confounder. For a variable to be a confounder, it must meet three specific criteria, as shown in the causal diagram below.

Causal Pathways in Confounding

A confounder is a risk factor for the outcome that is also associated with the exposure but does not reside in the causal pathway between the exposure and the outcome [41] [47]. For example, in an investigation of the association between coffee consumption and heart disease, smoking status could be a confounder. Smoking is a known cause of heart disease and is also associated with coffee-drinking habits, yet it is not an intermediate step between drinking coffee and developing heart disease [43]. If not accounted for, this confounding could make it appear that coffee causes heart disease.

Common Types of Confounding in Research

Several specific types of confounding frequently arise in observational studies of medical treatments: