Hamilton's Rule and Kin Selection: Evolutionary Foundations, Modern Applications, and Research Implications

This comprehensive review examines Hamilton's rule (rB > C) as the foundational principle of kin selection theory, exploring its mathematical foundations, empirical validations across diverse taxa, and ongoing theoretical debates.

Hamilton's Rule and Kin Selection: Evolutionary Foundations, Modern Applications, and Research Implications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines Hamilton's rule (rB > C) as the foundational principle of kin selection theory, exploring its mathematical foundations, empirical validations across diverse taxa, and ongoing theoretical debates. For researchers and scientists, we analyze methodological approaches for quantifying inclusive fitness parameters in natural populations, address conceptual challenges including non-linear interactions and non-kin social evolution, and synthesize evidence from comparative phylogenetic analyses and experimental studies. The article further discusses emerging research directions and potential implications for understanding social behaviors in biological systems, with relevance for biomedical research exploring evolutionary constraints on behavior and cooperation.

The Theoretical Foundation of Hamilton's Rule and Inclusive Fitness

The theory of evolution by natural selection, as articulated by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species, faced an immediate challenge: how to explain the existence of sterility and altruistic behaviors in social insects. Darwin recognized that the existence of sterile ant and bee castes, which help their queen produce offspring without reproducing themselves, presented a "special difficulty, which at first appeared to me insuperable, and actually fatal to my whole theory" [1]. Darwin's solution to this puzzle was to suggest that selection could act upon the family, proposing that a sterile ant's traits could be propagated through its fertile relatives [1]. This insight—that natural selection might favor traits that benefit genetic relatives even at a cost to the individual—represented the conceptual precursor to modern kin selection theory. However, this initial concept lacked the mathematical formalism necessary for precise predictions about the evolution of altruistic behavior, leaving it as an intriguing but undeveloped idea for nearly a century.

The core problem remained unresolved: how could altruism, defined as behavior that benefits others at a cost to oneself, evolve through natural selection? If natural selection favors traits that increase an individual's own survival and reproduction, then altruistic traits that reduce personal fitness should be eliminated from populations. This evolutionary paradox demanded a rigorous scientific explanation that would eventually emerge through mathematical formalization.

The Path to Formalization: Key Conceptual Advances

The conceptual foundation for kin selection developed gradually through the early 20th century, with several key thinkers building upon Darwin's initial insight. R.A. Fisher briefly alluded to the principle in 1930, but it was J.B.S. Haldane who first articulated the quantitative genetic logic underlying kin selection in the 1950s [1]. Haldane reportedly joked that he would willingly lay down his life for two brothers or eight cousins, intuitively grasping the fundamental genetic calculus [1]. He recognized that from a gene's perspective, saving multiple relatives could compensate for personal loss because relatives share identical copies of genes by descent. In 1955, Haldane provided a more formal explanation: "If the child's your own child or your brother or sister, there is an even chance that this child will also have this gene, so five genes will be saved in children for one lost in an adult" [1]. This conceptual breakthrough established the fundamental principle that altruism could evolve if the benefits to relatives, weighted by their genetic relatedness, exceeded the costs to the altruist.

Table: Historical Development of Kin Selection Theory

| Year | Scientist | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1859 | Charles Darwin | Identified sterile insects as a potential problem for natural selection | First proposed selection could act on the family |

| 1930 | R.A. Fisher | Briefly mentioned principle of family selection | Early conceptual precursor |

| 1955 | J.B.S. Haldane | Provided quantitative genetic explanation for altruism | "I would lay down my life for two brothers or eight cousins" |

| 1964 | W.D. Hamilton | Derived general mathematical rule for evolution of altruism | Formalized Hamilton's rule: rB > C |

| 1970 | George R. Price | Developed more elegant mathematical treatment using covariance | Price equation provided new foundation for social evolution theory |

| 1964 | John Maynard Smith | Coined term "kin selection" | Established standard terminology for the field |

Despite these conceptual advances, a comprehensive and general mathematical framework was still lacking. The field required a formal model that could predict under what specific conditions altruistic traits would evolve, and how different factors—the cost to the altruist, the benefit to the recipient, and the genetic relationship between them—would interact to determine evolutionary outcomes. This formalization would eventually emerge through the work of W.D. Hamilton, who synthesized these earlier insights into a general mathematical rule.

Hamilton's Mathematical Formulation

In 1964, W.D. Hamilton published a series of papers that would revolutionize the study of social evolution. Hamilton's great insight was that natural selection operates at the level of the gene, and that genes can propagate copies of themselves not only through an individual's own reproduction but also through the reproduction of genetic relatives [2]. This led to the concept of inclusive fitness, which combines an individual's direct fitness (through personal reproduction) with its indirect fitness (through effects on the reproduction of relatives) [1]. From this foundation, Hamilton derived his famous rule, which provides the precise conditions under which altruism will evolve.

Hamilton's rule states that an altruistic trait will be favored by natural selection when:

rB > C

Where:

- r = the genetic relatedness between actor and recipient (probability that they share identical copies of a gene by descent)

- B = the benefit to the recipient (increase in reproductive success)

- C = the cost to the actor (decrease in reproductive success) [3] [2]

The profound implication of Hamilton's rule is that altruism can evolve even when it reduces the personal fitness of the actor, provided that the benefits are sufficiently directed toward genetic relatives. Hamilton proposed two primary mechanisms through which kin selection could operate: (1) kin recognition, where individuals can directly identify their relatives, and (2) viscous populations, where limited dispersal ensures that local interactions tend to be among relatives by default [1].

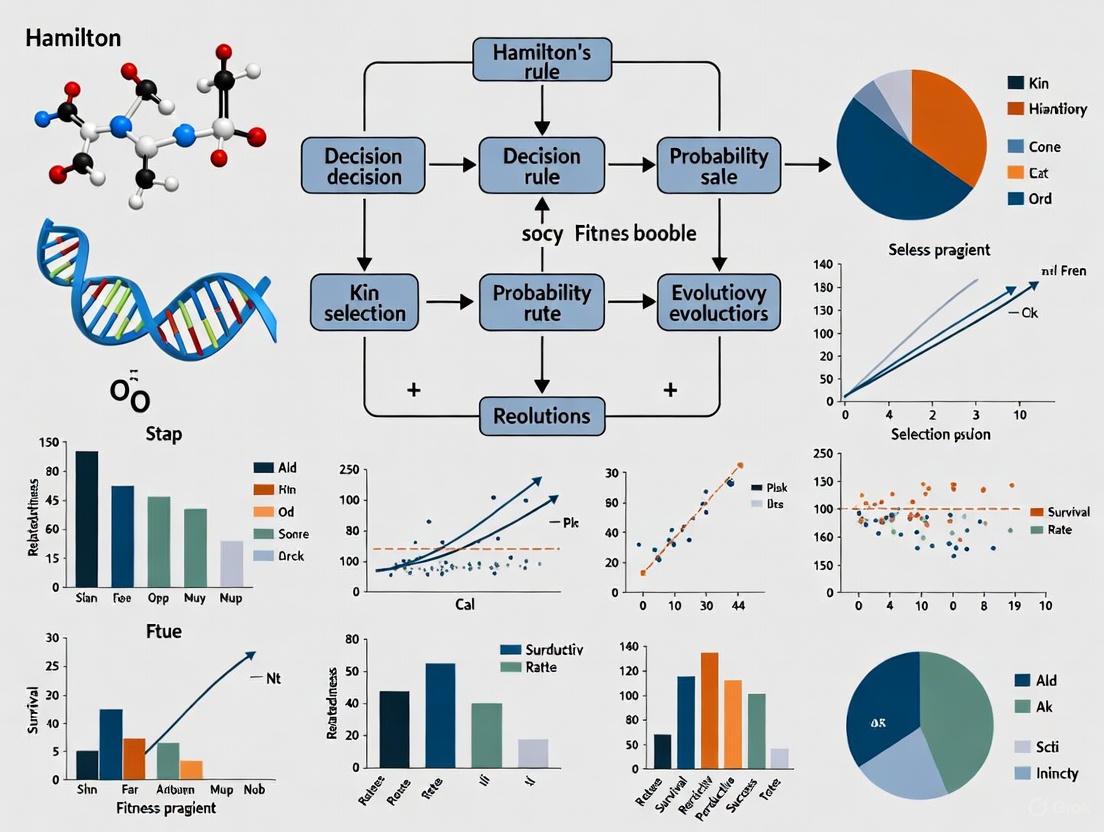

Diagram 1: Logical relationship between components of Hamilton's rule and the evolution of altruistic behavior.

Hamilton's original formulation defined relatedness (r) using Sewall Wright's coefficient of relationship, which gives the probability that at a random locus, the alleles will be identical by descent [1]. Modern formulations often use Alan Grafen's definition based on linear regression theory [1]. The costs and benefits in Hamilton's rule are measured in terms of reproductive fitness—the expected number of offspring—though in practice, proxies such as survival probability or economic resources may be used [2].

Table: Genetic Relatedness (r) Values in Diploid Organisms

| Relationship | Genetic Relatedness (r) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Identical twins | 1.0 | Same genetic identity |

| Parent-offspring, Full siblings | 0.5 | Share half of genes |

| Grandparent-grandchild, Half-siblings, Aunt/uncle-niece/nephew | 0.25 | Share quarter of genes |

| First cousins | 0.125 | Share one-eighth of genes |

| Unrelated individuals | 0 | No shared genes by descent |

Experimental Validation and Quantitative Testing

Early Empirical Support

Initial support for Hamilton's rule came from observational studies across diverse taxa. A particularly compelling example comes from lion behavior, where a female lion with a well-nourished cub may nurse a starving cub of her full sister [3]. In this case, the benefit to the sister (B = one offspring that would otherwise die) more than compensates for the cost to herself (C = approximately one-quarter of an offspring), and given that the genetic relatedness between full sisters is 0.5, Hamilton's rule (0.5 × 1) > 0.25 is satisfied [3]. Similarly, a study of red squirrels in Yukon, Canada, found that surrogate mothers adopted related orphaned squirrel pups but not unrelated orphans, with adoption occurring precisely when rB > C [1].

Robotics Experiment

A groundbreaking quantitative test of Hamilton's rule was conducted using simulated groups of foraging robots [4]. This experimental system allowed researchers to precisely manipulate the costs and benefits of altruistic behavior and measure the evolution of altruism across hundreds of generations. The robots were placed in a foraging arena with food items and could choose to allocate fitness rewards from successfully transported items either to themselves (selfish behavior) or share them equally with other group members (altruistic behavior) [4].

Experimental Protocol: Robotics Study

- Subjects: 200 groups of 8 Alice robots (2×2×4 cm) equipped with motorized wheels, infrared distance sensors, and vision sensors

- Apparatus: Foraging arena with one white wall and three black walls, containing 8 food items

- Genome: 33 genes encoding connection weights of a neural network that processed sensory information and determined behavior

- Selection: 500 generations of selection where probability of transmitting genomes was proportional to individual fitness

- Experimental Manipulation: Five different cost-to-benefit ratios (c/b: 0.01, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 0.99) crossed with five relatedness values (r: 0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00), with 20 independently evolving populations per treatment

- Measurement: Level of altruism defined as proportion of food items shared with other group members [4]

The results demonstrated remarkable agreement with Hamilton's rule predictions. The level of altruism rapidly increased over generations when r > c/b, remained near zero when r < c/b, and showed intermediate levels with high between-population variance when r = c/b (as expected under drift) [4]. This study provided the first quantitative test of Hamilton's rule in a system with a complex mapping between genotype and phenotype, demonstrating its accuracy even in the presence of pleiotropic and epistatic effects.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow of the robotics study testing Hamilton's rule.

Human Economic Decision-Making

Further experimental support comes from studies of human economic decision-making. Researchers employed techniques from experimental economics to measure how an individual's maximal willingness to pay for a $50 gift to another person varied with genetic relatedness [2]. The experimental design eliminated strategic behavior by ensuring subjects were best off indicating their true cutoff values.

Experimental Protocol: Human Economic Decisions

- Primary Question: "What is the maximal amount of money you are willing to pay for a recipient to receive $50 from us?"

- Recipients: Sibling (r=0.5), half-sibling (r=0.25), cousin (r=0.125), nonidentical twin (r=0.5), identical twin (r=1), randomly chosen student (r=0)

- Hypothetical Question: Maximal risk to own life to save recipient's life

- Subjects: 256 individuals

- Controls: Years sharing same residence, age, sex, favorite/least favorite relative

- Prevention of Side Payments: Formal commitment not to request money back from recipients [2]

The results showed strong agreement with Hamilton's rule (R² = 0.94), with willingness to pay increasing linearly with genetic relatedness [2]. Multivariate regression analysis revealed that almost all variation was explained by genetic relatedness, with similar but weaker patterns for hypothetical life-risk scenarios. This study demonstrated that Hamilton's rule accurately predicts human decision-making in economic contexts, suggesting evolutionary principles extend to modern human behavior.

Table: Key Experimental Tests of Hamilton's Rule

| Study System | Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foraging robots | Artificial evolution over 500 generations with manipulated c/b ratios and relatedness | Transition in altruism level consistently occurred when r > c/b | [4] |

| Human economic decisions | Measurement of willingness-to-pay for monetary transfers to relatives | Willingness to pay increased linearly with genetic relatedness (R² = 0.94) | [2] |

| Red squirrels | Observation of adoption patterns of orphaned pups | Adoption occurred when rB > C, but not when rB < C | [1] |

| Lion behavior | Observation of allonursing (shared nursing) behavior | Females nursed relatives when Hamilton's rule satisfied | [3] |

Modern Theoretical Refinements and Debates

While Hamilton's rule provides an elegant conceptual framework, its application to specific biological systems has prompted ongoing theoretical refinements. A significant development has been the integration of quantitative genetics with social evolution theory. Rather than focusing solely on genealogical relatedness, modern approaches define relatedness using statistical correlations based on the theory of linear regression [1] [5]. This perspective has led to quantitative genetic versions of Hamilton's rule that can be estimated using standard selection analysis.

A particularly important refinement accounts for indirect genetic effects (IGEs)—the influence of an individual's genotype on the phenotype and fitness of social partners [5]. When IGEs are present, evolutionary change depends on both direct and social selection, leading to an expanded version of Hamilton's rule that incorporates these additional components of selection. The social selection gradient (βS) corresponds to Hamilton's benefit (B), while the non-social selection gradient (βN) corresponds to Hamilton's cost (-C) [5].

Recent debates have focused on the "exact and general" formulation of Hamilton's rule (HRG), which some proponents claim is as general as natural selection itself [6]. Critics argue that in this formulation, Hamilton's rule cannot make predictions and cannot be tested empirically because the parameters B and C depend on the change in average trait value that the rule is supposed to predict [6]. In this formulation, Hamilton's rule can only "predict" data that have already been collected, making it a rearrangement of the data rather than a predictive model [6]. Despite these controversies, Hamilton's rule continues to provide a foundational framework for understanding the evolution of social behavior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Approaches

Table: Essential Methodological Approaches for Kin Selection Research

| Method/Technique | Application in Kin Selection Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Regression-based relatedness | Estimating genetic relatedness using statistical correlations | More practical than genealogical methods in natural populations |

| Artificial evolution | Testing evolutionary hypotheses in controlled systems | Allows manipulation of parameters impossible in natural systems |

| Experimental economics | Measuring human decision-making in social contexts | Provides quantitative measures of costs and benefits |

| Quantitative genetics | Partitioning selection into social and non-social components | Requires measurements of traits and fitness in natural populations |

| Genomic methods | Direct estimation of genetic relatedness and identification of genes affecting social behavior | Increasingly accessible with next-generation sequencing |

| Usp7-IN-10 | Usp7-IN-10, MF:C26H29ClN4O3S, MW:513.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ivermectin B1 monosaccharide | Ivermectin B1 monosaccharide, MF:C41H62O11, MW:730.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The historical development from Darwin's dilemma to Hamilton's mathematical formulation represents one of the most significant advances in evolutionary biology since Darwin. What began as Darwin's struggle to explain sterile insects has evolved into a sophisticated quantitative framework that predicts the evolution of social behavior across diverse taxa. Hamilton's rule (rB > C) provides an elegantly simple yet powerfully general explanation for how altruism can evolve through kin selection. Despite ongoing theoretical debates and refinements, empirical tests—from foraging robots to human economic decisions—continue to support Hamilton's fundamental insight that natural selection operates at the genetic level, favoring traits that maximize inclusive fitness. The integration of quantitative genetics with social evolution theory promises to further refine our understanding of how social behaviors evolve in natural populations, ensuring that Hamilton's rule remains a cornerstone of evolutionary biology.

Hamilton's rule is the foundational principle of inclusive fitness theory, providing a mathematical framework to predict the evolution of social behaviors, particularly altruism, through kin selection [1] [7]. It posits that a trait will be favored by natural selection when the genetic relatedness between actor and recipient, multiplied by the benefit to the recipient, exceeds the cost to the actor [3]. This is formally expressed by the inequality:

rB > C

Where:

- r = genetic relatedness of the recipient to the actor

- B = additional reproductive benefit gained by the recipient

- C = reproductive cost to the individual performing the act [1] [3]

This rule successfully resolved Darwin's paradox of altruistic behaviors that appear to reduce an individual's direct fitness, demonstrating how such traits can evolve by enhancing the reproductive success of genetic relatives [1] [7].

Theoretical Foundations and Parameter Definitions

Genetic Relatedness (r)

Genetic relatedness (r) represents the probability that two individuals share identical copies of a gene through recent common descent [1]. Formally, it is defined as "the probability that a gene picked randomly from each at the same locus is identical by descent" [1]. This parameter quantifies the genetic similarity between social partners beyond random assortment in the population.

The coefficient ranges from 0 (no genetic similarity) to 1 (identical genomes). In diploid organisms, r follows predictable values based on kinship:

- Parent-offspring: 0.5

- Full siblings: 0.5

- Grandparent-grandchild: 0.25

- Half-siblings: 0.25

- First cousins: 0.125 [1]

J.B.S. Haldane famously captured this concept by joking he would "lay down his life for two brothers or eight cousins," reflecting the equivalent genetic representation in future generations [1].

Benefit (B) and Cost (C)

Benefit (B) represents the increase in reproductive success (typically measured in offspring equivalents) experienced by the recipient of an altruistic act [3]. This benefit must be quantified in terms of its contribution to future generations.

Cost (C) represents the decrease in reproductive success suffered by the actor performing the behavior [3]. Both parameters are measured in the same currency of reproductive fitness, enabling direct comparison through Hamilton's inequality.

The following table summarizes the core parameters of Hamilton's Rule:

Table 1: Core Parameters of Hamilton's Rule

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Measurement | Example Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relatedness | r | Probability alleles are identical by descent | Regression coefficient | 0.5 (full siblings), 0.25 (half-siblings) |

| Benefit | B | Increase in recipient's reproductive success | Offspring equivalents | 1 offspring saved from predation |

| Cost | C | Decrease in actor's reproductive success | Offspring equivalents | 0.25 offspring due to predation risk |

Quantitative Experimental Evidence

Empirical studies across diverse taxa have successfully parameterized Hamilton's rule, demonstrating its predictive power in natural populations. The following table synthesizes key experimental findings:

Table 2: Empirical Tests of Hamilton's Rule in Natural Populations

| Species | Behavior | Relatedness (r) | Benefit (B) | Cost (C) | rB > C | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) | Adoption of orphaned pups | Variable by litter size | Increased orphan survival | Decreased surrogate offspring survival | Adoption occurred only when rB > C | [1] |

| Female lion (Panthera leo) | Nursing sister's starving cub | 0.5 (full sister) | 1 offspring saved | ~0.25 offspring | (0.5 × 1) > 0.25 → Yes | [3] |

| Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) | Kin discrimination in cannibalism | Variable | Fitness gain from cannibalizing non-kin | Fitness cost of cannibalizing kin | Supports Hamilton's rule | [7] |

| Wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) | Cooperative lekking | Variable | Increased mating success | Cost of helping | Supports Hamilton's rule | [7] |

| White-fronted bee-eater (Merops bullockoides) | Helping at nest | Variable | Increased production of young | Lost direct reproduction | Supports Hamilton's rule | [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Kin-Selected Adoption in Red Squirrels

Background: A 2010 study on wild red squirrels in Yukon, Canada, provided a rigorous empirical test of Hamilton's rule by examining adoption behavior [1].

Methodology:

- Field Monitoring: Researchers monitored squirrel populations intensively to document natural orphanings and subsequent adoption events.

- Relatedness Assessment: Used genetic markers to quantify relatedness (r) between potential adoptive mothers and orphans.

- Benefit Quantification: Measured B as the increased survival probability of orphaned pups following adoption.

- Cost Assessment: Calculated C as the decrease in survival probability of the surrogate mother's existing litter after adding an orphan.

- Predictive Testing: Compared the product rB to C for each potential adoption scenario.

Findings: Females consistently adopted orphans when rB exceeded C, but never adopted when rB was less than C, providing striking confirmation of Hamilton's predictive power [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Kin Selection Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis | Microsatellite markers, SNP genotyping, DNA sequencers | Relatedness quantification | Determine coefficient of relatedness (r) between individuals |

| Field Monitoring | GPS tracking, camera traps, telemetry systems | Behavioral observation | Document natural behaviors and interactions in wild populations |

| Fitness Metrics | Nest monitoring, pedigree analysis, demographic modeling | Benefit/Cost measurement | Quantify reproductive success and survival outcomes |

| Statistical Software | R packages (asreml, related), MATLAB | Data analysis | Calculate relatedness, perform regression analyses, test Hamilton's inequality |

| Experimental Manipulation | Cross-fostering, resource supplementation | Hypothesis testing | Manipulate relatedness or costs/benefits to test causal relationships |

| Hdac6-IN-46 | Hdac6-IN-46, MF:C26H21N3O4, MW:439.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cdk7-IN-32 | Cdk7-IN-32, MF:C24H35N5O2Si, MW:453.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Considerations and Modern Theoretical Developments

Kin Competition and Grafen's Extension

Kin selection does not operate in isolation. Kin competition - where relatives compete for limited resources - can reduce or negate altruism benefits [8]. Grafen's extension incorporates this effect:

r˯yᵦB - C - r˯eᵦd > 0

Where:

- r˯yᵦ = altruist's relatedness to beneficiary (standard r)

- r˯eᵦ = altruist's relatedness to individuals facing increased competition from beneficiary

- d = fitness decrement from increased competition [8]

This explains why limited dispersal, while increasing local relatedness, may not favor altruism due to intensified competition among relatives [8].

Genomic Applications and Caste-Antagonistic Pleiotropy

Modern evolutionary biology investigates how kin selection shapes genomic architecture [9]. In social insects, caste-antagonistic pleiotropy occurs when distinct castes have different phenotypic optima for traits controlled by the same genes [9].

Caste-Antagonistic Selection This genetic conflict creates evolutionary tension, with research showing that multiple mating by queens reduces regions where worker-favored alleles fix, potentially impeding worker caste evolution [9].

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

While powerful, applying Hamilton's rule presents methodological challenges:

Parameter Estimation: Precisely measuring B and C in natural populations requires extensive longitudinal demographic data [7].

Regression-Based Formulations: Modern formulations define parameters using multivariate regression, where:

- r = regression relatedness of recipient genotype on actor genotype

- B and C = partial regression coefficients of fitness on recipient and actor genotypes [6]

Some critics argue this "general" formulation can become tautological, as B and C may depend on the trait change to be predicted [6]. Nevertheless, Hamilton's rule remains empirically productive when parameters are independently measurable [7].

The parameters of Hamilton's rule - relatedness (r), benefit (B), and cost (C) - provide a robust conceptual and mathematical framework for investigating social evolution. Through rigorous empirical testing across diverse taxa, researchers have confirmed the rule's predictive power while extending its applications to incorporate kin competition, genomic conflicts, and complex social dynamics. Contemporary research continues to refine measurement methodologies and theoretical foundations, maintaining Hamilton's rule as an essential tool for understanding the evolution of social behavior.

The theories of inclusive fitness and kin selection represent foundational pillars in the modern understanding of social evolution. While often used interchangeably, these concepts possess distinct meanings and scopes within evolutionary biology. Inclusive fitness is a broader conceptual framework that quantifies an individual's genetic success through both direct reproduction and effects on the reproduction of others, regardless of genetic relatedness. In contrast, kin selection is a specific evolutionary process that operates through genetic similarity brought about by common ancestry, serving as a primary mechanism through which inclusive fitness is achieved [10] [11].

This technical guide examines the conceptual boundaries and intersections between these two theories, framed within the context of Hamilton's rule as a unifying mathematical principle. The distinction is not merely semantic but carries significant implications for research design and interpretation in animal behavior, particularly in empirical tests of social evolution hypotheses. As Grafen (2006) notes, inclusive fitness theory applies to genetic similarity however caused, whether by common ancestry, assortation of genotypes, or kin recognition, while kin selection specifically requires relatedness through common ancestry [11].

Conceptual Foundations and Theoretical Framework

Defining Inclusive Fitness

Inclusive fitness represents a comprehensive framework for understanding how natural selection shapes social behaviors. Formally defined by W.D. Hamilton in 1964, inclusive fitness partitions an individual's expected genetic success into two components: direct fitness derived from personal reproduction, and indirect fitness derived from influencing the reproduction of others with whom the individual shares genes [10] [12]. This theory emerged to explain how natural selection could favor behaviors that are costly to the actor's direct reproduction but benefit recipients.

The power of inclusive fitness lies in its generality. It is considered the most general answer to what organisms are selected to maximize because it satisfies two key criteria: (1) natural selection favors genes that increase inclusive fitness, and (2) inclusive fitness is under an organism's control, determined only by that organism's traits [12]. When social interactions are absent, inclusive fitness simplifies to maximizing direct reproductive success, making classical fitness optimization a special case of inclusive fitness theory [12].

Defining Kin Selection

Kin selection describes the evolutionary process whereby traits evolve because of their beneficial effects on the fitness of genetic relatives. Unlike inclusive fitness (which is a quantitative measure), kin selection is a process—specifically, the process by which altruistic behaviors spread through populations due to their positive effects on reproducing relatives [10] [11]. Kin selection relies on positive relatedness driven primarily by identity by descent from common ancestry [11].

The classic example of kin selection occurs in eusocial insects, where sterile workers forgo personal reproduction to support the queen's reproductive output. These behaviors evolve because workers are closely related to the queen's offspring, thus indirectly passing on their shared genes [10]. Kin selection provides a sufficient explanation for the evolution of altruism when genetic similarity arises through common ancestry, though other mechanisms like reciprocity can also promote cooperation [10].

Hamilton's Rule as the Unifying Principle

Hamilton's rule provides the mathematical foundation that bridges inclusive fitness and kin selection. Expressed by the inequality ( rb - c > 0 ), where ( r ) is genetic relatedness, ( b ) is benefit to the recipient, and ( c ) is cost to the actor, this rule specifies the conditions under which altruistic traits evolve [10] [7] [3]. Hamilton's rule demonstrates quantitatively that altruism can be favored by natural selection when the indirect fitness benefits (( rb )) exceed the direct fitness costs (( c )).

The rule follows naturally from partitioning fitness into direct and indirect components and enables predictions about how average trait values evolve in populations [10]. Hamilton's rule has been empirically tested across diverse taxa, with studies demonstrating that altruism occurs even when sociality is facultative, is typically under positive selection via indirect fitness benefits exceeding direct fitness costs, and commonly generates indirect benefits by enhancing the productivity or survivorship of kin [7].

Figure 1: Conceptual relationship between inclusive fitness, kin selection, and Hamilton's rule. Inclusive fitness provides the overarching framework, while kin selection is one process that contributes to indirect fitness. Hamilton's rule mathematically formalizes the conditions for social evolution.

Key Conceptual Distinctions

Scope of Application

The primary distinction between inclusive fitness and kin selection lies in their scope of application. Inclusive fitness represents a general theory of what natural selection maximizes, applying to all social behaviors regardless of how genetic similarity arises [12] [11]. Kin selection, meanwhile, specifically describes the process by which altruism evolves through interactions among genetic relatives who share genes by common descent [11].

This distinction becomes crucial when considering scenarios where genetic similarity arises through mechanisms other than kinship. For instance, in cases of assortative interactions based on genotype or direct assessment of genetic similarity, inclusive fitness theory still applies, but the process cannot be strictly classified as kin selection [11]. Hamilton himself emphasized this distinction, noting that inclusive fitness applies to genetic similarity however caused, while reserving "kin selection" for situations where relatedness arises specifically through common ancestry [11].

Mathematical and Analytical Frameworks

The relationship between inclusive fitness and kin selection can be further clarified through their mathematical representations. Inclusive fitness is calculated as the sum of direct fitness components (independent of social partners) and indirect fitness components (dependent on social partners), weighted by relatedness [10]. Kin selection emerges as a specific case within this broader framework when relatedness is positive due to common ancestry.

An important mathematical counterpart to inclusive fitness is neighbour-modulated fitness, which represents the conceptual inverse. While inclusive fitness calculates how a focal individual affects others' fitness, neighbour-modulated fitness calculates how others affect the focal individual's fitness [10] [12]. These frameworks are mathematically equivalent for predicting evolutionary outcomes but offer different analytical perspectives [10].

Table 1: Conceptual distinctions between inclusive fitness and kin selection

| Aspect | Inclusive Fitness | Kin Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Conceptual framework quantifying genetic success through direct and indirect effects | Evolutionary process through which traits evolve due to benefits to genetic relatives |

| Primary Reference | Hamilton (1964) [10] | Hamilton (1964) [10] |

| Scope | Applies to all social interactions, regardless of relatedness cause | Specifically applies to interactions among genetic relatives |

| Key Components | Direct fitness + Indirect fitness | Genetic relatedness + Fitness effects on kin |

| Mathematical Formulation | Sum of direct and relatedness-weighted indirect fitness components | Hamilton's rule (( rb - c > 0 )) applied to kin |

| Relationship | General theory of what selection maximizes | Specific process contributing to inclusive fitness |

Quantitative Frameworks and Empirical Testing

Hamilton's Rule in State-Structured Populations

In realistic biological scenarios where individuals vary in age, size, or other state variables, Hamilton's rule incorporates reproductive value to account for differential contributions to future generations. The modified rule becomes ( rb'V{recipient} - c'V{actor} > 0 ), where ( V{recipient} ) and ( V{actor} ) represent the reproductive values of recipient and actor, and ( b' ) and ( c' ) represent immediate changes in survival or reproduction [13].

Reproductive value, introduced by Fisher (1930), quantifies the expected contribution of an individual in a given state to the future population [13]. This extension is particularly important for long-lived species like many mammals, where immediate fitness measures may not accurately reflect long-term genetic contributions. For example, helping a young relative with high reproductive value may provide greater indirect fitness benefits than helping an older relative with lower reproductive value, even with identical relatedness [13].

Empirical Tests of Hamilton's Rule

Empirical tests of Hamilton's rule in natural populations, while challenging, have provided quantitative support for both inclusive fitness theory and kin selection. Bourke (2014) reviewed 12 studies across diverse taxa that empirically estimated r, b, and c parameters [7]. The findings demonstrated that: (1) altruism occurs even when sociality is facultative, (2) altruism is generally under positive selection via indirect fitness benefits exceeding direct fitness costs, and (3) social behavior commonly generates indirect benefits by enhancing kin productivity or survivorship [7].

Table 2: Empirical evidence for Hamilton's rule across diverse taxa (adapted from Bourke, 2014 [7])

| Taxon/Species | Social Behaviour | Relatedness (r) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lace bug (Gargaphia solani) | Female egg dumping | >0 | Positively selected via indirect fitness benefits [7] |

| Allodapine bee (Exoneura pubescens) | Usurped female guards shared nest | >0 | Positively selected via indirect fitness benefits [7] |

| Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) | Larva cannibalizes non-kin versus kin | >0 | Kin discrimination positively selected [7] |

| Wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) | Male cooperative lekking | 0.5 | Positively selected via indirect fitness benefits |

| White-fronted bee-eater (Merops bullockoides) | Helping at nest | >0 | Positively selected via indirect fitness benefits [7] |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Microbial Mix Experiments

Microbial systems have become important for quantitative tests of social evolution theory due to their tractability for fitness measurements. A common experimental design is the mix experiment, which investigates fitness effects of microbial interactions by manipulating local genotype frequency [14]. These experiments typically measure how genotype fitness changes when individuals interact compared to when they are separate, allowing researchers to estimate social effects on fitness.

The canonical approach applies either neighbour-modulated fitness (kin selection) or multilevel selection frameworks to analyse these data. For neighbour-modulated fitness, researchers use regression models of the form ( w \sim g + G ), where ( w ) is fitness, ( g ) is individual genotype, and ( G ) is mean group genotype [14]. The direct effect of genotype is estimated by the slope with respect to ( g ), while the indirect (social) effect is estimated by the slope with respect to ( G ).

Figure 2: Workflow for microbial mix experiments to quantify social evolution parameters. This experimental approach allows precise measurement of direct and indirect fitness effects underlying inclusive fitness and kin selection.

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential methodological approaches for studying inclusive fitness and kin selection

| Method/Tool | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial mix experiments | Quantifying direct and indirect fitness effects [14] | Requires controlled manipulation of genotype frequencies; enables high-replication fitness measurements |

| Molecular relatedness estimation | Measuring genetic relatedness (r) using molecular markers [7] | Based on microsatellites, SNPs, or whole-genome sequencing; requires population genetic statistics |

| Reproductive value calculations | Estimating long-term fitness in state-structured populations [13] | Uses Leslie/Lefkovitch matrices; requires detailed demographic data (survival, fecundity by state) |

| Neighbour-modulated fitness regression (( w \sim g + G )) | Partitioning direct and indirect fitness components [14] | g = focal genotype, G = group mean genotype; assumes additive effects |

| Multilevel selection analysis | Separating within-group and between-group selection [14] | W ~ G (among-group selection), Δw ~ 1 (within-group selection); mathematically equivalent to kin selection |

Research Challenges and Future Directions

Methodological Limitations

Current research faces several methodological challenges in testing predictions derived from inclusive fitness and kin selection. In long-lived vertebrates, direct estimation of fitness benefits (b) and costs (c) in Hamilton's rule is often impractical, as lifetime fitness data spanning multiple generations is required [13]. Additionally, standard regression approaches used in neighbour-modulated fitness frameworks assume weak, additive fitness effects, which may not hold in microbial systems where strong selection and non-additive effects are common [14].

These limitations have prompted the development of alternative approaches, such as focusing on the product of relatedness and reproductive value rather than attempting to measure b and c directly [13]. This approach is particularly valuable for field studies of mammals and other long-lived species where comprehensive fitness data is unavailable.

Integration with Cultural Evolution

Recent theoretical work has explored extending inclusive fitness theory to human cultural evolution. Baumard and André (2025) propose modelling cultural dynamics using ecological and evolutionary theory frameworks, with inclusive fitness as a central component [12] [15]. This approach treats cultural traits as analogous to genes, with cultural transmission occurring through both direct teaching and indirect social influences.

The eco-evolutionary perspective offers a parsimonious approach to conceptualizing cultural evolution, drawing parallels between genetic and cultural transmission pathways [12]. This represents an promising frontier for inclusive fitness theory, potentially providing a unified framework for understanding both biological and cultural social evolution.

Inclusive fitness and kin selection, while conceptually related, serve distinct roles in evolutionary theory. Inclusive fitness provides the overarching framework for understanding what natural selection maximizes—the sum of direct and relatedness-weighted indirect fitness components. Kin selection describes the specific process by which altruism evolves through interactions among genetic relatives who share genes by common descent. Hamilton's rule provides the mathematical foundation unifying these concepts, specifying the conditions (( rb - c > 0 )) under which altruistic traits evolve.

For researchers investigating social behaviors, recognizing this distinction is crucial for appropriate experimental design and interpretation. Microbial mix experiments offer powerful approaches for quantitative tests, while reproductive value considerations enhance predictions for state-structured populations. As research extends into new domains including cultural evolution, the conceptual clarity between inclusive fitness as a general framework and kin selection as a specific process becomes increasingly important for theoretical advancement and empirical testing.

The evolution of altruism presents a fundamental challenge to evolutionary theory: how can natural selection favor traits that are costly to the individual performing them while benefiting others? Such behaviors appear paradoxical under the framework of individual selection, where traits are expected to enhance the direct reproductive success of their bearers. The solution emerged through the groundbreaking work of W.D. Hamilton, who introduced the concept of inclusive fitness and provided a mathematical framework now known as Hamilton's rule [1]. This rule states that a gene for altruism will spread when rb > c, where c represents the fitness cost to the altruist, b the fitness benefit to the recipient, and r their genetic relatedness [1]. This principle, termed kin selection, explains how altruism can evolve through the indirect reproduction of shared genes in biological relatives, thereby resolving the apparent evolutionary paradox and providing a powerful explanatory framework for the widespread occurrence of cooperative behaviors across animal societies.

Theoretical Foundations: Hamilton's Rule and Kin Selection

The Mathematical Basis of Hamilton's Rule

Hamilton's rule (rb > c) provides a simple yet powerful inequality that predicts when altruistic traits will evolve. The relatedness parameter (r) quantifies the probability that two individuals share identical copies of a gene by descent from a common ancestor [1]. The conceptual breakthrough was recognizing that selection can favor traits that reduce an individual's direct fitness when these behaviors sufficiently enhance the fitness of genetic relatives who likely carry the same alleles. This inclusive fitness perspective expands the concept of evolutionary success to include both direct reproduction and effects on the reproduction of kin [1] [16].

The theoretical generality of Hamilton's rule has been extensively debated, with questions about its applicability to non-linear fitness effects and complex genetic architectures. Recent work has addressed these concerns through the development of a Generalized Price Equation, which demonstrates that multiple nested versions of Hamilton's rule exist, each appropriate for different biological circumstances [17]. The simplest version applies to linear fitness effects with independent interactions, while more complex versions accommodate non-linear and interdependent fitness effects [17]. This hierarchical framework establishes that Hamilton's rule remains valid when properly specified for the evolutionary system under study.

Mechanisms Generating Assortment

The fundamental requirement for altruism to evolve is positive assortment between individuals carrying altruistic genotypes and the helping behaviors they receive [18]. Kin selection represents one powerful mechanism for generating such assortment, but not the only one. Hamilton originally proposed two primary mechanisms: kin recognition, where individuals directly identify their relatives, and viscous populations, where limited dispersal creates local neighborhoods of relatives by default [1]. When individuals can recognize kin, they can target their altruism specifically toward those with whom they share genes. In the absence of such recognition, population viscosity alone can facilitate altruism through spatial structure that keeps relatives in proximity [1].

The assortment framework reveals that genetic relatedness per se is not an absolute requirement for altruism, but rather one particularly effective mechanism for creating the correlation between genotype and altruistic receipt necessary for altruism to evolve [18]. Even seemingly paradoxical cases of suicidal aid can theoretically evolve without help being exchanged among genetically similar individuals if other mechanisms create sufficient assortment between altruistic genotypes and the helping behaviors they receive [18].

Empirical Evidence and Quantitative Tests

Experimental Evolution in Robotic Systems

A landmark quantitative test of Hamilton's rule employed experimental evolution with simulated foraging robots over hundreds of generations [4]. This system enabled precise manipulation of the costs and benefits of altruistic behavior while controlling genetic relatedness.

Table 1: Experimental Parameters in Robot Foraging Study

| Parameter | Description | Experimental Manipulation |

|---|---|---|

| Cost (c) | Fitness cost to altruist | Controlled via fitness points allocated for shared vs. non-shared food items |

| Benefit (b) | Fitness benefit to recipient | Controlled via distribution of fitness rewards from transported food items |

| Relatedness (r) | Genetic similarity between interactants | Varied from 0 to 1 across experimental treatments |

| c/b ratio | Cost-to-benefit ratio | Systematically manipulated across five values (0.01, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0) |

The robots were equipped with neural networks whose connection weights were encoded in their genomes, creating a complex mapping between genotype and phenotype [4]. This allowed researchers to observe how social behaviors evolved under different relatedness and cost-benefit conditions. The results demonstrated that Hamilton's rule accurately predicted the minimum relatedness necessary for altruism to evolve across all experimental treatments, despite the presence of pleiotropic and epistatic effects that are not directly accounted for in the original 1964 formulation [4].

Human Familial Altruism and Paternity Uncertainty

Human studies provide compelling evidence for kin selection in familial contexts. Recent research with 9,128 participants investigated how paternity uncertainty shapes perceptions of familial kindness [19]. The results demonstrated that relatives with lower paternity uncertainty were rated as significantly kinder than those with higher uncertainty (β = -0.148, t(31,910) = -6.23, p < 0.001) [19]. This pattern reflects evolved psychological adaptations sensitive to differences in genetic certainty, with maternal grandmothers (no paternity uncertainty) rated kindest and paternal grandfathers (two steps of paternity uncertainty) rated lowest in kindness [19].

Table 2: Kindness Ratings by Familial Relationship and Paternity Uncertainty

| Relationship | Paternity Uncertainty Steps | Mean Kindness Rating | Genetic Relatedness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | 0 | Highest | 0.5 |

| Maternal Grandmother | 0 | High | 0.25 |

| Maternal Grandfather | 1 | Intermediate | 0.25 |

| Father | 1 | Intermediate | 0.5 |

| Paternal Grandmother | 1 | Intermediate | 0.25 |

| Paternal Grandfather | 2 | Lowest | 0.25 |

These findings support the prediction that altruistic investment is calibrated according to genetic relatedness, with adjustments for lineage-specific uncertainty in relatedness [19]. The results also revealed that daughters consistently rated their biological parents higher than sons, potentially reflecting lower paternity uncertainty through female offspring [19].

Methodological Approaches and Research Tools

Experimental Evolution Protocols

The robotic foraging study [4] employed a sophisticated experimental evolution protocol:

Robot Specifications and Arena Setup:

- Eight Alice robots (2×2×4 cm) and eight food items were placed in a foraging arena with one white wall and three black walls

- Robots equipped with two motorized wheels, three infrared distance sensors (3cm range for food detection), one infrared sensor (6cm range for robot distinction), and two vision sensors for wall color perception

- Six sensors connected to a neural network with six input neurons, three hidden neurons, and three output neurons controlling wheel speeds and food sharing behavior

Genome and Evolutionary Algorithm:

- Genome encoded 33 connection weights of the neural network determining sensory processing and behavioral responses

- Populations consisted of 200 groups of 8 robots each, evolved over 500 generations

- Selection probability proportional to individual fitness based on foraging performance

- Selected genomes subjected to crossover and mutation to create 1,600 new genomes for each subsequent generation

Parameter Manipulation and Measurement:

- Five different c/b ratios (0.01, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0) combined with five relatedness values (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0)

- Twenty independently evolving populations for each of the 25 treatment combinations

- Level of altruism measured as the proportion of food items shared with other group members

Quantitative Genetic Frameworks

Evolutionary quantitative genetics offers powerful methods for measuring the parameters of Hamilton's rule in natural populations [5]. The quantitative genetic version partitions evolutionary change into phenotypic components (selection gradients) and genetic components (relatedness and genetic variances) [5]. Specifically, the non-social selection gradient (βN) corresponds to Hamilton's cost (C), while the social selection gradient (βS) corresponds to the benefit (B) [5]. This approach allows estimation of Hamilton's rule parameters using standard selection analysis techniques while incorporating indirect genetic effects (IGEs) that account for the genetic influence of social environments [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Kin Selection Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Evolution Systems | High-precision manipulation of genetic parameters | Foraging robots with programmable genomes [4] |

| Physics-based Simulations | Modeling of physical and dynamical properties | Simulation of robot foraging dynamics [4] |

| Neural Network Architectures | Complex genotype-phenotype mapping | Robot behavioral control systems [4] |

| Genetic Relatedness Estimators | Quantification of relatedness coefficients | Wright's coefficient of relationship [1] |

| Social Selection Gradient Analysis | Measurement of social effects on fitness | Quantitative genetic versions of Hamilton's rule [5] |

| Paternity Uncertainty Metrics | Assessment of relatedness certainty in human studies | Kindness rating surveys across kinship lines [19] |

Contemporary Debates and Theoretical Refinements

The Limits of Hamilton's Rule

While Hamilton's rule provides a fundamental principle for understanding altruism evolution, its application to complex biological systems has generated ongoing debates. Some researchers argue that the rule, while mathematically correct, may be insufficient to explain certain evolutionary trajectories, particularly in cases of reproductive division of labor [20]. For example, the predicted facilitative effect of monogamy on the evolution of helping behavior does not always emerge in population models, suggesting that ecological factors and life history constraints can override relatedness considerations [20].

The role of genetic relatedness versus other factors remains particularly contentious in explaining the evolution of eusociality. While high relatedness was historically considered essential for the evolution of sterile castes, comparative analyses reveal numerous evolutionary transitions to multiple mating and reduced within-group relatedness without corresponding increases in group conflict [20]. This suggests that factors beyond relatedness, including social heterosis benefits from genetic diversity and mechanisms for conflict suppression, may be important in maintaining social cohesion [20].

Integration with Alternative Frameworks

The debate surrounding Hamilton's rule has increasingly recognized the complementary nature of different evolutionary frameworks. The assortment perspective highlights that kin selection represents one specific mechanism for generating the correlation between altruistic genotypes and received benefits necessary for altruism to evolve [18]. Similarly, the quantitative genetic approach demonstrates how Hamilton's rule can be integrated with models of phenotypic evolution through the decomposition of selection into social and non-social components [5].

Recent theoretical work has developed a general version of Hamilton's rule using the Generalized Price Equation, which generates multiple nested rules appropriate for different biological circumstances [17]. This framework shows that specific versions of Hamilton's rule are always mathematically correct but only biologically meaningful when based on appropriately specified models for the evolutionary system under study [17]. The hierarchy ranges from simple rules for non-social traits with linear fitness effects to complex rules accommodating non-linear and interdependent fitness effects [17].

Hamilton's rule remains a foundational principle for understanding the evolution of altruism, with robust empirical support from both experimental systems and natural populations. The simple inequality rb > c captures the essential condition for altruism to evolve through kin selection, while contemporary refinements have expanded its applicability to complex biological scenarios. The integration of quantitative genetic approaches and the development of generalized versions have strengthened the theoretical framework, allowing for more precise empirical tests and applications.

Ongoing debates reflect the healthy maturation of the field rather than fundamental weaknesses in the theory. The recognition that Hamilton's rule operates within a broader evolutionary context, interacting with ecological constraints, life history strategies, and other forms of selection, enriches our understanding of social evolution. Future research will benefit from continued integration of different methodological approaches, from experimental evolution to quantitative genetics, to further elucidate how genetic relatedness and other forms of assortment shape the evolution of altruistic behaviors across biological systems.

The gene's-eye view of evolution, often termed the "selfish gene" concept, represents a fundamental framework in evolutionary biology by positing that the gene is the smallest entity capable of evolution by natural selection [21]. This perspective shifts the focus from individual organisms to genes as the primary units of selection, with organisms functioning as "vehicles" or "survival machines" built by genes to ensure their own replication and propagation [21] [22]. From this vantage point, complex evolutionary phenomena, including altruistic behaviors and sociality, can be reinterpreted as strategies through which genes maximize their representation in future generations.

Within this conceptual framework, kin selection emerges as a powerful evolutionary mechanism that can be understood as a form of group selection operating at the genetic level. When WD Hamilton first formulated his theory of inclusive fitness, he explicitly grounded it in genetic relatedness, arguing that "the ultimate criterion that determines whether a gene for altruism will spread is not whether the behavior is to the benefit of the behaver but whether it is of benefit to the gene" [22]. This gene-centered perspective reveals how altruistic behaviors can evolve when they benefit copies of the same gene residing in related individuals, thus reframing apparent group-level phenomena as manifestations of gene-level selection.

This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundations, mathematical formalisms, and experimental methodologies that connect the gene's-eye view to kin selection theory, with particular emphasis on contemporary generalizations of Hamilton's rule and their application to current research in evolutionary biology and beyond.

Theoretical Framework: Connecting Gene's-Eye View to Kin and Group Selection

The Gene as the Fundamental Unit of Selection

The gene's-eye perspective emerged through the work of evolutionary biologists including George Williams and Richard Dawkins, who built upon earlier population genetic principles established by Fisher, Haldane, and others [22]. This viewpoint recognizes that while organisms are temporary assemblages of traits, genes potentially persist across generations through replication. As Dawkins argued in "The Selfish Gene," organisms function as sophisticated vehicles constructed by genes to ensure their own propagation [23]. This conceptual reversal—viewing organisms as instruments of gene replication rather than genes as instruments of organismal fitness—provides profound insights into evolutionary puzzles.

From this perspective, natural selection occurs through the differential survival of alternative alleles competing for representation in future gene pools. Genes that produce phenotypic effects that enhance their own replication success will inevitably increase in frequency, even if those effects sometimes reduce the survival or reproduction of individual organisms carrying them. This fundamental insight explains how "selfish genetic elements" can persist despite their harmful effects on individual fitness [22]. The logic of genic selection also provides a powerful explanatory framework for understanding the evolution of altruistic behaviors through kin selection.

Hamilton's Rule and Inclusive Fitness from a Gene's-Eye View

Hamilton's rule, traditionally expressed as br > c, provides a mathematical condition for the evolution of altruism [24]. In this formulation, b represents the benefit to the recipient, c the cost to the actor, and r their genetic relatedness. From a gene's-eye perspective, this rule can be understood as quantifying when helping a relative represents a more effective strategy for propagating copies of the altruism gene than direct reproduction.

The following table summarizes the key parameters of Hamilton's rule from a gene-centered perspective:

| Parameter | Traditional Definition | Gene's-Eye Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| b | Benefit to recipient | Increase in reproductive success of copies of the altruism gene in the recipient |

| c | Cost to actor | Decrease in reproductive success of the altruism gene in the actor |

| r | Genetic relatedness | Probability that the recipient carries a copy of the altruism gene identical by descent |

When a gene can enhance the reproductive success of copies of itself in relatives more than it reduces its own reproductive success in the actor, natural selection will favor altruistic behaviors. This concept of inclusive fitness combines direct fitness (reproduction through personal offspring) and indirect fitness (reproduction through effects on relatives' offspring) [21]. The honey bee's suicidal stinger provides a classic example: a gene for barbed stingers may kill the individual but save numerous relatives who carry copies of the same gene [21].

Kin Selection as Genetic Group Selection

The gene's-eye view reveals kin selection as a form of group selection where the "group" is defined not by geographical or ecological boundaries but by genetic relatedness. From this perspective, relatives constitute a group of individuals who share statistically similar genetic compositions, particularly at loci relevant to social behaviors.

This genetic group selection operates through two complementary mechanisms:

Limited dispersal - When individuals interact primarily with relatives, genes for altruism naturally benefit copies of themselves, creating a selective advantage at the gene level despite potential costs at the individual level.

Kin recognition - When organisms can detect genetic relatedness, altruism can be directed specifically toward those who share the altruism gene.

The following DOT script illustrates the logical relationships between these concepts:

Methodological Advances: Generalizing Hamilton's Rule for Complex Systems

The Limitations of Classical Hamilton's Rule

While Hamilton's rule provides an elegant conceptual framework, its application to real-world systems has proven challenging. The standard approach defines benefits and costs as regression coefficients from linear models [17] [24]. However, empirical studies, particularly in microbial systems, have demonstrated that this linear approach is often poorly specified for real biological systems [14]. The canonical fitness models of both kin and multilevel selection theories frequently fail because they cannot accommodate the strong selection and non-additive effects widespread in microbial systems [14].

These limitations are particularly evident in "mix experiments," where researchers manipulate local genotype frequency to investigate fitness effects of microbial interactions [14]. When analyzing datasets from such experiments, the linear regression approach often provides poor fits to empirical data, as measured by information-theoretic criteria like AIC [14]. This indicates that the biological reality of social interactions involves complexities that cannot be captured by simple linear models.

Van Veelen's Generalized Hamilton's Rule

Recent theoretical work has addressed these limitations through a generalized version of Hamilton's rule. Van Veelen (2025) developed a framework that extends Hamilton's rule to accommodate arbitrary nonlinear relationships between genotypes and fitness [17] [24]. This approach uses the Generalized Price Equation, which generates multiple Price-like equations corresponding to different statistical models of how fitness depends on genetic makeup [17].

The generalized framework allows researchers to incorporate higher-order terms to capture nonlinear and interactive effects. For example, if helping behavior has a quadratic effect on reproductive success, Hamilton's rule can be rewritten as:

bâ‚€,â‚râ‚€,â‚ + bâ‚€,â‚‚râ‚€,â‚‚ > c

where bâ‚€,â‚ and bâ‚€,â‚‚ quantify linear and quadratic effects of helping, and râ‚€,â‚ and râ‚€,â‚‚ quantify corresponding measures of genetic relatedness [24]. Similarly, interaction effects between the propensities of both parties to cooperate can be included by adding terms of the form bâ‚–,áµ£râ‚–,áµ£ [24].

The following table compares the classical and generalized versions of Hamilton's rule:

| Aspect | Classical Hamilton's Rule | Generalized Hamilton's Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | br > c | Σ(bₖ,ᵣrₖ,ᵣ) > c |

| Fitness Effects | Linear, additive | Nonlinear, interactive |

| Relatedness | Single linear coefficient | Multiple higher-order coefficients |

| Model Specification | Fixed | Chosen based on biological context |

| Predictive Power | Limited to linear systems | Adaptable to complex systems |

| Application to Data | Often poor fit | Improved fit through appropriate specification |

The Generalized Price Equation

The foundation of this generalized approach is the Generalized Price Equation, which repairs the "broken link between the Price equation and statistics" [17]. The original Price equation in covariance form is:

w̄Δp̄ = Cov(w,p) + E(wΔp)

where w̄ is average fitness, Δp̄ is change in average p-score, Cov(w,p) is the covariance between fitness and p-score, and E(wΔp) is the expected value of the product of fitness and change in p-score [17].

The Generalized Price Equation replaces realized fitnesses (w) with model-predicted fitnesses (ŵ) based on a statistical model that includes at minimum a constant term and a linear term for the p-score:

w̄Δp̄ = Cov(ŵ,p) + E(wΔp) [17]

This generalized form creates not one Price equation but "a Price-like equation for every possible true model" [17]. Each represents an identity that holds generally, but their biological meaning depends on appropriate model specification.

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Methodologies for Studying Kin Selection

Research on kin selection and the gene's-eye view employs diverse methodological approaches across different biological systems:

Mix experiments in microbial systems represent a powerful experimental design for investigating kin selection [14]. These experiments typically involve:

- Genotype manipulation - Creating controlled mixtures of different genotypes at varying frequencies while holding total population size constant

- Fitness measurement - Tracking changes in genotype frequencies over time through absolute abundance counts

- Fitness calculation - Computing Wrightian fitness (w) as final absolute abundance divided by initial abundance, or Malthusian fitness (m) as ln(w) [14]

- Regression analysis - Applying neighbor-modulated fitness models (w ∼ g + G) or multilevel selection models to quantify selection parameters

Sociogenomic approaches in social insects integrate genomic tools with evolutionary theory:

- Caste-specific transcriptomics - Comparing gene expression patterns between reproductive and sterile castes

- Population genomics - Analyzing patterns of sequence variation within and between populations

- Selection tests - Identifying signatures of selection on genes with different social effects [25]

Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Experiments

The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications in kin selection research:

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Microbial Strains | Isogenic lines with genetic markers | Mix experiments to measure frequency-dependent fitness effects [14] |

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Transcriptome profiling | Caste- and sex-specific gene expression analysis in social insects [25] |

| Genotyping Arrays | Genotype frequency measurement | Tracking allele frequency changes in evolution experiments [14] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Visual marker genes | Labeling different genotypes in mixed cultures [14] |

| Selective Media | Environment manipulation | Creating specific selection pressures in experimental evolution |

Quantitative Analysis Frameworks

The analysis of kin selection experiments requires appropriate statistical frameworks:

Neighbor-modulated fitness approach (kin selection):

- Models fitness as: w ∼ g + G

- Where g is individual genotype and G is group mean genotype [14]

- The coefficient for g represents direct fitness effects

- The coefficient for G represents indirect fitness effects

Multilevel selection approach:

- Models group fitness: W ∼ G

- Models within-group selection: Δw ∼ 1 [14]

- The slope of W with respect to G represents between-group selection

- Mean Δw represents within-group selection

Model selection criteria:

- Use information-theoretic approaches (AIC) to compare model fits [14]

- Compare linear and nonlinear models for the same datasets

- Evaluate whether social effects are better modeled with additive or interactive terms

The following DOT script visualizes the experimental workflow for kin selection research:

Research Implications and Future Directions

Applications Beyond Evolutionary Biology

The gene's-eye view of kin selection has implications extending beyond traditional evolutionary biology:

Medical and drug development applications:

- Understanding the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations

- Designing combination therapies that account for social interactions among pathogens

- Developing cancer treatments that consider cellular cooperation within tumors

Microbiome research:

- Analyzing cooperative and competitive interactions in microbial communities

- Understanding stabilization of commensal relationships

- Manipulating microbial ecosystems for health benefits

Synthetic biology:

- Designing microbial consortia with stable cooperative interactions

- Engineering kin-based control mechanisms in synthetic ecosystems

Current Research Frontiers

Several emerging areas represent particularly active research frontiers:

Integration of ecological and evolutionary genomics: Recent conferences highlight growing interest in "dynamics of ecological and evolutionary change" at genomic levels [26]. This includes understanding how selection acts across multiple loci and traits simultaneously, and how genomic diversity is influenced by ecological interactions [26].

Nonlinear social evolution: The recognition that "real-world cooperation cannot be captured by simple linear models" has stimulated research on nonlinear interactions [24]. This includes studying:

- Threshold effects in collective action

- Synergistic benefits of cooperation

- Network effects in social populations [24]

Cross-scale integration: Major funding initiatives emphasize research that "integrate[s] levels of scale, for example from genes to species to communities, from local to global processes, or across ecological and evolutionary time scales" [27]. This recognizes that understanding social evolution requires connecting gene-level processes to population-level outcomes.

Methodological Recommendations

Based on current research findings, we recommend:

Move beyond linear models - Default to model comparison approaches that include nonlinear terms rather than assuming linearity [14] [24]

Use appropriate fitness metrics - Select Wrightian or Malthusian fitness measures based on biological context and research question [14]

Apply information-theoretic criteria - Use AIC and similar measures to compare alternative models rather than relying solely on statistical significance [14]

Validate parameter constancy - Ensure that estimated parameters remain constant across population compositions when applying generalized Hamilton's rule [17]

Integrate multiple approaches - Combine kin selection and multilevel selection perspectives to gain complementary insights into social evolution [14] [22]

The gene's-eye view of kin selection as group selection continues to provide profound insights into the evolution of social behavior. While the classical formulation of Hamilton's rule remains conceptually important, recent theoretical advances that accommodate biological complexity promise to enhance both the explanatory and predictive power of social evolution theory. As research in this field progresses, integration across biological scales and methodological approaches will be essential for deepening our understanding of how genes shape social behaviors across the tree of life.

Quantifying Kin Selection: Methodological Approaches and Empirical Applications

Experimental Designs for Measuring r, B, and C in Natural Populations

Hamilton's rule, expressed by the inequality ( rB > C ), provides a foundational framework for understanding the evolution of social behaviors, particularly altruism, through kin selection [1]. In this formulation, ( r ) represents the genetic relatedness between the actor and recipient, ( B ) the benefit to the recipient's fitness, and ( C ) the cost to the actor's fitness [7] [1]. While the theory is well-established, empirically measuring these parameters in natural populations presents significant methodological challenges. This guide synthesizes current methodologies for quantifying ( r ), ( B ), and ( C ), providing researchers with practical tools for testing Hamilton's rule in field settings. The accurate measurement of these parameters is essential for moving beyond theoretical predictions to empirically validated explanations of social evolution across diverse taxa.

Defining the Core Parameters of Hamilton's Rule

A precise understanding of the parameters ( r ), ( B ), and ( C ) is a prerequisite for their empirical measurement.

Relatedness (( r )): This coefficient measures the genetic similarity between two individuals compared to the population average. Formally, it is the probability that two individuals share alleles identical by descent at a given locus [1]. Values range from 1 (identical twins) through 0.5 (full siblings), 0.25 (half-siblings/grandparent-grandchild), and 0.125 (first cousins) to 0 (unrelated individuals).

Benefit (( B )): This parameter quantifies the increase in the lifetime direct fitness of the recipient that is causally attributable to the social actor's behavior. Benefits typically manifest as increased survival rates, fecundity, or mating success [7].

Cost (( C )): This parameter measures the decrease in the lifetime direct fitness of the social actor resulting from performing the altruistic behavior. Like benefits, costs are measured in terms of reduced survival or reproductive output [7].

Critically, ( B ) and ( C ) must be measured in the same currency, typically lifetime reproductive success, to ensure a valid application of Hamilton's rule [7].

Methodologies for Measuring Relatedness (( r ))

Determining genetic relatedness is a foundational step in testing Hamilton's rule, and several approaches have been developed.

Table 1: Methods for Estimating Relatedness (( r )) in Natural Populations

| Method | Description | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Markers | Uses neutral genetic markers (microsatellites, SNPs) to estimate allele sharing. | Tissue/blood samples for DNA extraction; genotyping platform. | High accuracy; directly measures genetic similarity; applicable to any population. | Requires specialized lab equipment and expertise; can be costly. |

| Pedigree Reconstruction | Constructs a multi-generational pedigree based on observed parent-offspring relationships. | Long-term behavioral and demographic data; often combined with genetic paternity/maternity analysis. | Intuitive connection to relatedness coefficients; provides social context. | Vulnerable to misassignment of parentage; requires long-term study. |

| Population Viscosity | Infers relatedness from spatial proximity in species with limited dispersal (viscous populations). | Data on individual spatial movements and dispersal distances. | Logistically simpler than genetic methods; useful for initial hypotheses. | Indirect proxy; can be inaccurate if dispersal patterns are complex. |

Experimental Workflow for Relatedness Estimation

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for estimating relatedness, integrating both field and laboratory approaches.

Diagram 1: Workflow for estimating relatedness (r) in natural populations.

Experimental Designs for Quantifying Benefits (( B )) and Costs (( C ))

Measuring the fitness effects of behaviors is the most challenging aspect of testing Hamilton's rule, as it requires demonstrating a causal relationship between a behavior and lifetime reproductive success.

Core Comparative Approaches

The fundamental design for measuring ( B ) and ( C ) involves comparing individuals in different states.

Measuring Cost (( C )): Researchers compare the fitness of actors performing the altruistic behavior against a control group of non-acting conspecifics under similar conditions. The control group should be individuals who are capable of performing the behavior but do not, or individuals from whom the behavior is experimentally prevented [7].

Measuring Benefit (( B )): Researchers compare the fitness of recipients who receive the altruistic act against a control group of individuals who do not receive the act. The difference in fitness outcomes (e.g., offspring survival, growth rate) represents ( B ) [7].

Table 2: Experimental Designs for Measuring B and C

| Design Type | Description | Application to B/C | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|