Life History Theory in Behavioral Ecology: An Evolutionary Framework for Biomedical Research and Substance Use Disorders

This article synthesizes life history theory (LHT), a core framework in evolutionary biology, to explore its profound implications for behavioral ecology and biomedical science.

Life History Theory in Behavioral Ecology: An Evolutionary Framework for Biomedical Research and Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

This article synthesizes life history theory (LHT), a core framework in evolutionary biology, to explore its profound implications for behavioral ecology and biomedical science. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we examine how adaptive life history strategies, shaped by environmental pressures, influence behavior, health, and disease vulnerability. The content spans from foundational concepts like the fast-slow continuum and trade-offs to methodological approaches for modeling human life courses. It tackles critical challenges in applying LHT to clinical contexts, validates theories through comparative analysis and empirical case studies—including a detailed look at young adult substance use—and concludes by outlining future translational research directions for prevention and treatment.

The Evolutionary Blueprint: Core Principles of Life History Theory

Life history strategy (LHS) represents a fundamental framework in evolutionary biology for understanding how organisms allocate limited resources to growth, reproduction, and survival throughout their lifespan. This technical guide traces the conceptual evolution from the historically significant r/K selection theory to the contemporary fast-slow continuum paradigm, examining the theoretical foundations, empirical evidence, and methodological approaches that underpin modern life history research. We synthesize current understanding of how environmental pressures shape life history trajectories across species and within populations, with particular attention to applications in behavioral ecology and translational research. The paper provides structured quantitative comparisons, experimental protocols, and specialized research tools to facilitate rigorous life history investigation across biological disciplines.

Life history theory investigates how natural selection designs organisms to allocate finite bio-energetic resources among competing functions of maintenance, growth, reproduction, and survival across their lifespan [1] [2]. This evolutionary framework posits that organisms face fundamental trade-offs in energy investment, where increased allocation to one fitness component (e.g., current reproduction) necessarily reduces available resources for others (e.g., future growth or survival) [1]. These strategic allocation patterns represent adaptive responses to environmental pressures that have shaped species-specific developmental trajectories and reproductive schedules across the tree of life.

The theoretical foundation of life history theory rests on the premise that organisms evolve to maximize their lifetime reproductive success within specific ecological constraints [2]. This optimization process generates predictable covariance among life history traits, creating strategic syndromes that range from fast-paced reproductive strategies characterized by early maturation and high offspring numbers to slow-paced strategies emphasizing prolonged development, extended parental investment, and longer lifespans [3]. Understanding the selective pressures that drive variation along this continuum provides critical insights into species survival tactics, population dynamics, and behavioral adaptations across diverse taxa.

Historical Foundation: r/K Selection Theory

Conceptual Framework and Mathematical Origins

The terminology of r/K-selection was formally coined by ecologists Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson in 1967 based on their work on island biogeography [4]. The theory derives from the logistic model of population growth, formalized in the Verhulst equation:

Where N represents population size, r denotes the intrinsic rate of natural increase, K signifies the carrying capacity of the environment, and dN/dt represents the rate of population change over time [4]. This mathematical foundation posited that selective pressures would diverge in environments favoring rapid population growth (r-selection) versus those favoring competitive efficiency at population densities near carrying capacity (K-selection).

r-selection predominates in unstable or unpredictable environments where resources are periodically abundant, favoring traits that maximize reproductive rates [4] [3]. In contrast, K-selection occurs in stable, resource-limited environments near carrying capacity, where competitive ability becomes paramount [4] [3]. The theory proposed that these contrasting selective regimes would shape integrated suites of life history traits, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of r-selected versus K-selected species

| Life History Trait | r-Selected Species | K-Selected Species |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive output | High fecundity, many offspring | Low fecundity, few offspring |

| Parental investment | Minimal parental care | Extensive parental care |

| Offspring size | Small offspring size | Large offspring size |

| Development rate | Rapid development, early maturation | Slow development, delayed maturation |

| Body size | Typically smaller body size | Typically larger body size |

| Lifespan | Short life expectancy | Long life expectancy |

| Competitive ability | Poor competitors | Strong competitors |

| Environmental adaptation | Adapted to unstable environments | Adapted to stable environments |

| Population dynamics | Variable population sizes, below carrying capacity | Stable population sizes, near carrying capacity |

| Example organisms | Insects, grasses, rodents | Elephants, whales, humans |

Empirical Applications and Theoretical Limitations

During its peak popularity in the 1970s-1980s, r/K selection theory served as a valuable heuristic device for interpreting life history variation across taxa [4] [3]. Researchers applied the framework to explain ecological succession patterns, noting that disturbed ecosystems are typically colonized by r-strategists, which are gradually replaced by K-strategists as the community approaches equilibrium [4]. The theory was also extended to study evolutionary ecology in diverse organisms, from bacteriophages to human inflammatory responses [4].

However, mounting empirical evidence revealed significant theoretical limitations. A critical review by Stearns (1977) highlighted ambiguities in interpreting empirical data, while Parry (1981) demonstrated no consensus among researchers about the precise definition of r- and K-selection [4]. Templeton and Johnson (1982) presented contradictory evidence showing Drosophila populations under K-selection actually produced traits associated with r-selection [4]. The theory struggled to explain species exhibiting mixed strategies, such as trees (K-selected traits but prolific offspring dispersal) and sea turtles (large body size but high offspring numbers) [4] [3].

The r/K selection paradigm was further criticized for oversimplifying life history variation along a single axis that combined disturbance and resource availability while neglecting other important selective factors like age-specific mortality patterns, dispersal dynamics, and abiotic stress tolerance [3]. By the early 1990s, these limitations led to declining use in ecological research, though the framework experienced a resurgence in psychology literature [3].

The Modern Synthesis: Fast-Slow Continuum

Theoretical Framework and Trait Covariation

The fast-slow continuum emerged as a more robust framework for understanding life history variation, focusing primarily on reproductive life history traits while accounting for the allometric influences of body size [3]. This paradigm characterizes species along a graded spectrum from fast life histories (characterized by early reproduction, short generation times, high fecundity, and rapid mortality) to slow life histories (featuring delayed reproduction, long generation times, low fecundity, and extended lifespans) [3].

Unlike r/K selection theory, the fast-slow continuum explicitly disentangles the confounding effects of body size, enabling more meaningful comparisons across taxa [3]. Some researchers define the continuum after removing body size effects, revealing that some small-bodied species (e.g., hummingbirds) may exhibit slow life history traits when measured per unit mass, while certain large species may show unexpectedly fast traits [3]. This refined approach has demonstrated greater predictive power for explaining life history variation across diverse taxa.

Table 2: The Fast-Slow Continuum of Life History Strategies

| Life History Dimension | Fast Strategy | Slow Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pace of reproduction | Early reproduction, short generation time | Delayed reproduction, long generation time |

| Reproductive investment | High fecundity, many offspring, small offspring size | Low fecundity, few offspring, large offspring size |

| Survival schedule | High mortality rates, short lifespan | Low mortality rates, long lifespan |

| Developmental pattern | Rapid development, early maturity onset | Slow development, extended juvenile period |

| Body size relationship | Generally smaller body size (with exceptions) | Generally larger body size (with exceptions) |

| Cognitive/behavioral traits | Greater risk-taking, short-term orientation | Greater deliberation, long-term planning |

| Environmental drivers | Harsh, unpredictable environments, high mortality risk | Stable, predictable environments, low mortality risk |

| Physiological correlates | Accelerated senescence, higher metabolic rates | Delayed senescence, efficient resource use |

Evidence for Multi-Axial Variation

Contemporary research indicates that a single fast-slow axis provides insufficient explanation for the full spectrum of life history diversity. Multi-species analyses reveal that the direction of trait correlations often differs substantially across taxonomic groups; for instance, the relationship between fecundity and other life-history traits reverses in fish compared to mammals [3]. Bielby et al. (2007) identified two primary axes of life history variation in mammals: one corresponding to the fast-slow continuum and another related to reproductive timing and energy allocation patterns [3].

This evidence suggests that life history variation is simultaneously constrained by body size (physical constraints), phylogeny (evolutionary history), and contemporary selection pressures associated with specific ecological "lifestyles" [3]. The recognition of multi-axial variation has prompted development of more sophisticated classification schemes, including tripartite systems that better accommodate plants, insects, and fish species that do not fit neatly along a single fast-slow dimension [3].

Methodological Approaches in Life History Research

Quantitative Variance Partitioning

Modern life history research employs sophisticated statistical partitioning techniques to decompose behavioral variation into environmental, among-individual, and within-individual components [5]. This approach quantifies several key aspects of individual variation:

- Animal personality: Repeatable individual differences in average behavioral expression across time and context, measured as the variance of a random intercept in mixed-effects models and quantified as repeatability (R) [5]

- Behavioral type: An individual's average behavioral expression, represented by the random intercept value of its reaction norm [5]

- Behavioral plasticity: Reversible changes in behavior in response to environmental gradients within the same individual, indicated by non-zero reaction norm slopes [5]

- Individual plasticity: Variation in responsiveness to environmental gradients among individuals, shown by differing reaction norm slopes [5]

- Behavioral predictability: Among-individual differences in residual within-individual variability around behavioral means [5]

- Behavioral syndromes: Correlations between an individual's average expression of different behaviors across multiple measurements [5]

This variance partitioning framework has been productively applied to movement ecology data, revealing individual differences in foraging specialization, habitat selection, and mobility patterns across diverse taxa including marine predators, terrestrial mammals, and birds [5].

Experimental Protocols for Life History Assessment

Protocol 1: Life History Trait Measurement in Longitudinal Studies

Objective: Quantify key life history parameters for positioning individuals/species along the fast-slow continuum.

Methodology:

- Cohort establishment: Mark and monitor individuals from birth or early development through senescence

- Demographic monitoring: Record age-specific mortality schedules, reproductive events, and growth trajectories

- Reproductive investment measurement: Document offspring number, size, and quality; quantify parental care duration and intensity

- Developmental timing assessment: Record age at maturity, gestation length, and interbirth intervals

- Data analysis: Calculate life table parameters including intrinsic growth rate (r), net reproductive value (Râ‚€), and generation time (G)

Applications: Comparative life history studies across populations/species; assessment of environmental influences on life history trajectories.

Protocol 2: Behavioral Syndrome Analysis

Objective: Identify correlated behavioral traits underlying life history strategies.

Methodology:

- Behavioral battery: Administer repeated standardized tests measuring risk-taking, exploration, aggression, and sociability

- Environmental manipulation: Expose subjects to controlled variation in resource availability, predation risk, or social context

- Behavioral coding: Quantify behavioral responses using standardized ethograms and automated tracking where possible

- Variance partitioning: Use mixed-effects models to separate among-individual from within-individual variation

- Correlation structure analysis: Calculate among-individual correlations between different behaviors to identify behavioral syndromes

Applications: Understanding the behavioral mechanisms linking environmental conditions to life history outcomes; identifying constraints on behavioral adaptation.

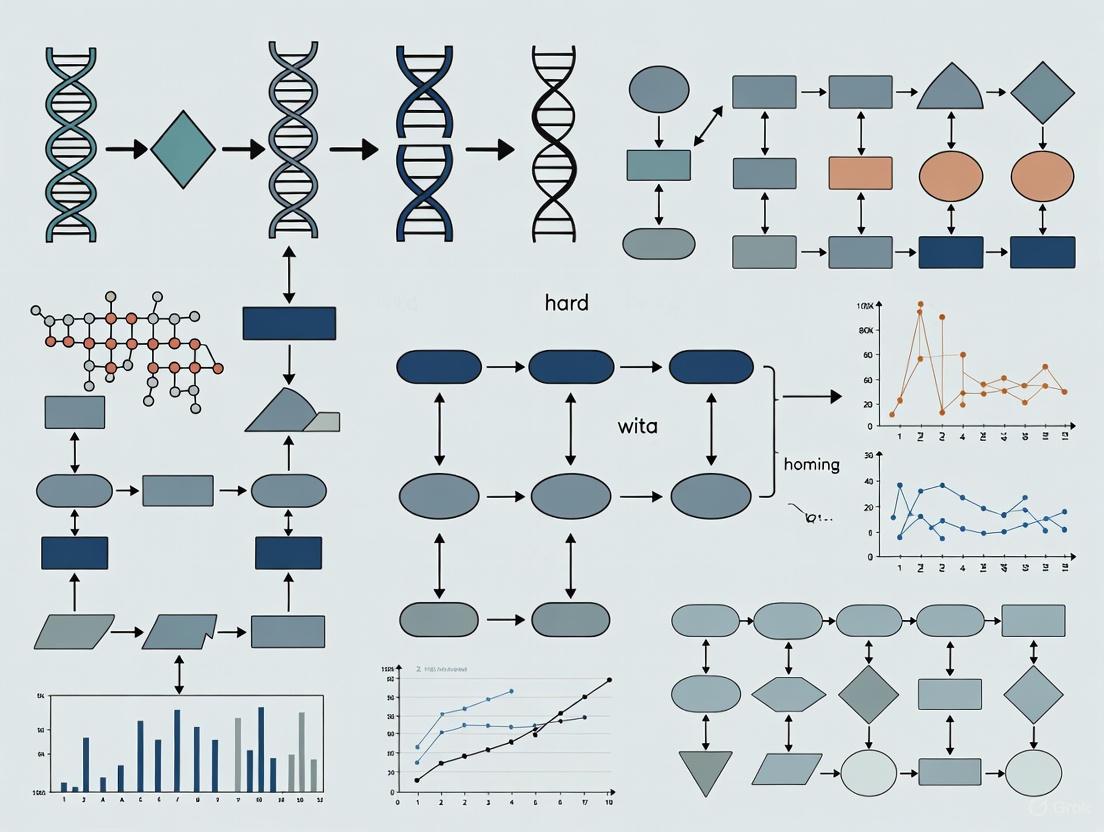

Visualization of Life History Theoretical Framework

Life History Strategy Framework: This diagram illustrates how environmental cues and mortality regimes shape fast versus slow life history strategies, which manifest through behavioral, physiological, and demographic correlates to ultimately determine fitness outcomes.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Life History Studies

| Research Tool | Application in Life History Research | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Long-term demographic monitoring | Tracking life history trajectories | Documenting survival, reproduction, and growth across lifetimes |

| Mixed-effects models | Variance partitioning | Quantifying among-individual vs. within-individual variation |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Testing multivariate relationships | Modeling complex pathways between environmental factors, traits, and fitness |

| Animal tracking technologies | Movement ecology studies | Recording individual movement patterns, space use, and habitat selection |

| Laboratory behavioral assays | Behavioral syndrome analysis | Standardized tests for risk-taking, exploration, aggression, and sociability |

| Life table analysis | Demographic parameter estimation | Calculating intrinsic growth rates, net reproductive value, and generation time |

| Hormonal profiling | Physiological mechanism investigation | Measuring stress hormones, metabolic markers, and reproductive hormones |

| Genetic relatedness analysis | Heritability estimation | Quantifying genetic contributions to life history variation |

Applications in Behavioral Ecology and Translational Research

Human Behavioral Ecology

Life history theory provides a powerful framework for understanding human behavioral variation across diverse socioecological contexts. Research has demonstrated that individuals exposed to harsh, unpredictable environments during development tend to exhibit faster life history strategies, characterized by earlier sexual debut, greater reproductive output, and risk-taking behaviors [1]. These strategic adjustments represent adaptive responses to environmental conditions that shape developmental trajectories and behavioral profiles.

Studies of historical human populations have revealed how mobility patterns reflect life history trade-offs, with residential mobility peaking during young adulthood (ages 20-30) when reproductive and resource acquisition efforts are maximized [6]. This life course patterning demonstrates how behavioral strategies are coordinated to optimize fitness across different life stages, with gender-specific modifications reflecting divergent selective pressures [6]. Contemporary research continues to elucidate how cues of environmental quality and mortality risk shape human mating strategies, parental investment, and risk sensitivity through psychological mechanisms calibrated to local conditions.

Substance Use and Health Outcomes

Life history framework has been productively applied to understanding patterns of substance use and addiction. Research indicates that fast life history strategies explain approximately 61% of the variance in overall liability for substance use among young adults [1]. This association reflects the operation of fundamental trade-offs between current and future reproduction, with fast strategists prioritizing immediate rewards despite potential long-term costs.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying substance use vulnerability appear to share common pathways with life history regulation, involving frontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, and dopaminergic systems [1]. This overlap suggests that substance use behaviors may emerge as byproducts of psychological adaptations calibrated to harsh, unpredictable environments where fast strategies prove advantageous. Interventions informed by life history principles may therefore prove more effective than one-size-fits-all approaches by addressing the adaptive functions that risky behaviors serve in specific contexts.

The conceptual evolution from r/K selection theory to the fast-slow continuum represents significant theoretical refinement in understanding life history variation. While r/K selection provided an important foundational framework, contemporary life history research emphasizes multi-axial trait covariation, explicit modeling of trade-offs, and sophisticated variance partitioning approaches. The fast-slow continuum offers greater explanatory power for understanding how environmental pressures shape developmental trajectories, reproductive schedules, and behavioral strategies across diverse taxa.

Future research directions include developing more comprehensive multi-axial classification systems, elucidating neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying life history trade-offs, and translating life history principles into targeted interventions for health-related behaviors. As methodological innovations continue to enhance our ability to quantify individual variation and plasticity, life history theory remains an indispensable framework for integrating evolutionary principles across biological disciplines, from behavioral ecology to translational medicine.

Life History Theory (LHT) provides an analytical framework for understanding how natural selection shapes the timing of key biological events and the allocation of an organism's energy to competing life functions. As a cornerstone of evolutionary ecology, LHT investigates the diversity of life history strategies across species, seeking to explain how traits such as age at maturity, offspring number, and lifespan are shaped by evolutionary pressures to maximize reproductive fitness [7]. These traits are not independent; they are interconnected through fundamental evolutionary trade-offs where resources allocated to one function, such as current reproduction, cannot be simultaneously allocated to another, such as somatic maintenance or growth [8] [9]. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of these core life history traits, the trade-offs that link them, and the experimental methodologies used to quantify them, framed for an audience of researchers and scientists in behavioral ecology and related disciplines.

Theoretical Foundations of Life History Trade-offs

The Evolutionary Principle of Trade-offs

The central tenet of LHT is that organisms face energetic and resource constraints that prevent the simultaneous maximization of all life history traits [8]. Natural selection therefore favors strategies that optimally allocate limited resources to growth, reproduction, and maintenance in a way that maximizes lifetime reproductive success [7] [9]. This principle is encapsulated in the cost of reproduction hypothesis, which posits that higher investment in current reproduction often comes at the expense of future growth, survival, or reproduction [7]. These trade-offs are mathematically represented through the concept of reproductive value (RV), where an organism's expected contribution to the population is the sum of its current reproduction and its residual reproductive value (RRV), which represents expected future reproduction [7].

r/K Selection Theory

r/K selection theory provides a framework for understanding how different ecological pressures shape life history strategies [10] [7]. Organisms in unpredictable or disturbed environments ( r-strategists ) are typically selected for a high growth rate (r), early maturation, high reproductive output, and shorter lifespans, with minimal parental investment per offspring. Conversely, organisms in stable, predictable environments near their environment's carrying capacity (K) ( K-strategists ) are selected for slower development, later maturation, fewer offspring, greater parental investment, and longer lifespans [10] [7]. This theory models the core trade-off between the number of offspring produced and the timing of reproduction.

Quantitative Analysis of Core Life History Traits

The following tables synthesize empirical data and theoretical predictions for the three core life history traits, highlighting their interrelationships and trade-offs.

Table 1: Key Life History Traits and Their Interrelationships

| Trait | Definition | Theoretical Trade-off | Empirical Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Maturity | The age at which an organism first reproduces. | Earlier maturity often trades off with smaller body size, reduced future growth, and higher mortality risk [7] [9]. | In Filipina women, earlier age at first birth is associated with accelerated epigenetic aging [10]. |

| Offspring Number | The number of progeny produced per reproductive event or lifetime. | Producing more offspring often trades off with reduced offspring quality (e.g., survival, size) and reduced parental survival [7] [8]. | Birds with larger broods cannot afford more prominent secondary sexual characteristics [7]. Collared Flycatchers with enlarged broods laid smaller clutches later in life [9]. |

| Lifespan | The typical length of an organism's life. | Longer lifespan requires investment in somatic maintenance and repair, trading off with energy available for reproduction [10] [9]. | In burying beetles, higher allocation to current reproduction correlated with shorter lifespans [7]. |

Table 2: Quantified Trade-offs from Empirical Studies

| Study System | Experimental Manipulation | Measured Trade-off | Quantitative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humans (H. sapiens) [10] | Longitudinal observation of pregnancy history | Pregnancy vs. Longevity | Each additional pregnancy was associated with accelerated epigenetic aging by ~2.6 months and a 0.65% increase in all-cause mortality risk. |

| Burying Beetles (N. spp) [7] | Observation of resource allocation | Current Reproduction vs. Lifespan | Individuals that allocated more resources to current reproduction had the shortest lifespans and fewest lifetime reproductive events. |

| Collared Flycatchers (F. albicollis) [9] | Experimental brood enlargement | Current vs. Future Reproduction | Birds rearing enlarged broods subsequently laid smaller clutches later in life compared to controls. |

| Drosophila (D. melanogaster) [9] | Laboratory selection for late-life reproduction | Early-life vs. Late-life Fitness | Selection for increased late-life fitness resulted in a correlated decrease in early-life reproductive output. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Life History Studies

Longitudinal Analysis of Reproductive Costs in Humans

Objective: To quantify the long-term impact of pregnancy on biological aging and mortality risk in a human population [10].

- Cohort Establishment: Recruit a large, longitudinal cohort (e.g., the Filipino cohort in Ryan et al., 2024) with detailed reproductive, health, and lifestyle data.

- Biological Age Assessment: Collect biological samples (e.g., blood) at multiple time points. Quantify biological age using epigenetic clocks (e.g., DNA methylation patterns) and other biomarkers like telomere length [10].

- Data Collection: Record key variables:

- Reproductive history: Number of pregnancies, age at first birth, breastfeeding duration.

- Lifestyle factors: Socioeconomic status, diet, smoking, exercise.

- Health outcomes: Morbidity and mortality data.

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Use regression models to isolate the effect of pregnancy number on the pace of epigenetic aging, controlling for chronological age and confounding lifestyle variables. Calculate hazard ratios for mortality risk.

Experimental Manipulation of Reproductive Effort in Birds

Objective: To empirically test the trade-off between current and future reproduction [9].

- Study Population: Monitor a wild (e.g., Collared Flycatchers) or captive bird population during the breeding season.

- Experimental Design: Randomly assign nests to two groups:

- Treatment Group: Manipulate brood size by adding or removing chicks shortly after hatching.

- Control Group: Handle chicks but do not alter brood size.

- Parental Monitoring: Track the survival and subsequent reproductive efforts of the parent birds.

- Data Collection:

- Current reproductive cost: Measure parental foraging effort, weight loss, and stress hormones (e.g., glucocorticoids).

- Future reproduction: Record clutch size, offspring quality, and laying date in the following breeding season(s).

- Survivorship: Document adult survival rates.

- Analysis: Compare future reproductive success and survival between the treatment and control groups using t-tests or ANOVA, establishing a causal link between reproductive effort and future fitness.

Visualization of Life History Trade-offs and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core trade-offs and the physiological pathways that connect reproduction and aging, as discussed in the literature.

Diagram 1: Resource trade-offs link reproduction and aging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Life History Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use in Life History Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Clock Panels | Set of CpG sites for DNA methylation analysis to estimate biological age. | Quantifying the pace of biological aging in longitudinal human studies, independent of chronological age [10]. |

| ELISA Kits for Hormone Assays | Quantify stress (e.g., glucocorticoids) and reproductive (e.g., testosterone, estrogen) hormones from blood, saliva, or fecal samples. | Measuring physiological costs of reproduction and stress in experimental manipulations (e.g., brood enlargement) [10] [9]. |

| Telomere Length Assay Kits | Measure telomere length, a biomarker of cellular aging, via qPCR or Southern blot. | Investigating the long-term somatic cost of high reproductive effort (e.g., in young mothers) [10]. |

| Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) & Camera Traps | Non-invasive monitoring of animal behavior, population counts, and movement ecology. | Long-term species monitoring to collect data on survival, reproduction, and resource use in natural populations [11]. |

| Computer Vision & Tracking Software | Automated analysis of video footage to track animal movement and behavior. | High-throughput, quantitative behavioral ecology, such as analyzing trade-offs between foraging effort (for reproduction) and vigilance [12]. |

| Cyanidin 3-xyloside | Cyanidin 3-xyloside, MF:C20H19ClO10, MW:454.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Otophylloside L | Otophylloside L, MF:C61H98O26, MW:1247.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of age at maturity, offspring number, and lifespan reveals the fundamental trade-offs that shape organismal life histories. As integrative frameworks like LHT continue to bridge evolutionary biology, ecology, and mechanistic physiology, they provide powerful tools for understanding the diversity of life strategies. Future research leveraging advanced biomarkers, genomic tools, and long-term ecological monitoring will further elucidate the complex interplay between genes, environment, and life history decisions, with broad implications for conservation biology, medicine, and behavioral sciences.

In evolutionary ecology, the trade-off between current reproduction and somatic effort represents a cornerstone of life history theory (LHT) [7] [13]. This analytical framework examines how organisms allocate finite energetic, physiological, and temporal resources among competing life functions, with profound consequences for fitness and survival [7] [9]. The fundamental principle posits that energetic investments in immediate reproductive success inevitably reduce resources available for somatic maintenance and repair, leading to accelerated physiological deterioration (senescence) and reduced future survival prospects [7] [9]. This trade-off arises from inescapable constraints that prevent the simultaneous maximization of all fitness components, thereby shaping the diversity of life history strategies observed across species and populations [8] [13].

The conceptual foundation rests on the diminishing force of natural selection with advancing age, as described by the "selection shadow" [9]. This creates conditions where genes with beneficial effects early in life (enhancing reproduction) can be favored by selection even if they carry detrimental late-life effects (reducing survival) – a concept known as antagonistic pleiotropy [9]. The Disposable Soma Theory further formalizes this as an optimal resource allocation problem: organisms should invest in somatic maintenance only to ensure acceptable function during their expected lifespan in a given environment, redirecting remaining resources to reproduction [9]. Consequently, increased extrinsic mortality risk typically selects for reduced investment in somatic repair and earlier, more intense reproduction [7] [9].

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Core Principles and Mathematical Representation

Life history theory predicts that the trade-off between reproduction and somatic maintenance will be resolved differently across environments and species to maximize lifetime reproductive success [8]. This optimization can be conceptually represented by the equation for Reproductive Value (RV): RV = Current Reproduction + Residual Reproductive Value (RRV) [7]. The RRV encapsulates an organism's future reproductive potential, which depends directly on investments in somatic effort that enhance future survival [7]. The cost of reproduction hypothesis explicitly states that higher investment in current reproduction directly compromises growth, survivorship, and future reproductive output [7].

The following conceptual diagram illustrates how this fundamental trade-off is modulated by ecological factors and manifests in physiological and life history outcomes:

Evolutionary Genetic Mechanisms

Two primary evolutionary mechanisms underpin the reproduction-somatic maintenance trade-off. Mutation Accumulation proposes that deleterious mutations with late-life effects escape effective natural selection and accumulate in populations, contributing to senescence [9]. More influential is Antagonistic Pleiotropy (AP), where genes that enhance early-life fitness (e.g., increasing fertility) are favored by selection despite having deleterious effects later in life (e.g., promoting cellular damage) [9]. Supporting evidence comes from laboratory selection experiments where populations selected for increased late-life fitness show correlated decreases in early-life reproductive output [9], and from molecular studies identifying specific alleles with opposing early- versus late-life effects [9].

Quantitative Evidence and Empirical Data

Comparative Life History Data Across Species

Empirical evidence for the reproduction-somatic effort trade-off spans multiple taxa and reveals how different ecological pressures shape life history strategies. The following table synthesizes key comparative data:

Table 1: Comparative Life History Traits Demonstrating Reproduction-Survival Trade-offs

| Species/Group | Age at First Reproduction | Reproductive Investment | Lifespan/Longevity | Key Trade-off Manifestation | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Salmon | Single reproductive bout at maturity | Semelparous; allocates all resources in one event | Dies shortly after spawning | Extreme current reproduction eliminates future survival | [7] |

| Humans | ~15-20 years | Iteroparous; few offspring over decades | ~70-80 years | High parental investment extends lifespan but limits reproductive rate | [7] |

| Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus spp.) | Early adulthood | Increased brood size manipulation | Reduced lifespan with higher investment | Negative correlation between brood size and parental lifespan | [7] |

| Collared Flycatcher (Ficedula albicollis) | 1 year | Experimentally enlarged broods | Reduced future reproduction & survival | Parents with enlarged broods laid smaller clutches later in life | [9] |

| Bank Vole (Clethrionomys glareolus) | Early season | Increased litter size | Reduced maternal survival | Experimental litter enlargement decreased mother survival | [9] |

| Cavefish (Amblyopsidae) | 2-3 years | Few, large eggs; low reproductive rate | Extended longevity (4-7+ years) | Low energy environment selects for slow pace of life | [13] |

| Drosophila (Selected Lines) | Artificially selected for early reproduction | High early-life fecundity | Reduced lifespan | Direct experimental evidence for genetic trade-off | [9] |

Experimental Manipulations of Reproductive Effort

Controlled experiments directly testing the cost of reproduction hypothesis provide compelling evidence for the trade-off. Key methodologies and findings include:

Table 2: Experimental Manipulations of Reproductive Effort

| Experimental Approach | Methodology | Key Findings | Implications for Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brood/Litter Size Manipulation | Artificially increasing or decreasing number of offspring parent must rear [9] | Birds and mammals with enlarged broods/litters showed: reduced survival [9]; reduced future reproduction [9]; or reduced offspring quality/size [9] | Direct energetic cost of reproduction depletes somatic resources |

| Laboratory Selection Experiments | Selecting model organisms (e.g., Drosophila) for late-life reproduction over generations [9] | Evolved populations showed increased longevity but decreased early-life fecundity as correlated response [9] | Genetic basis for trade-off; supports Antagonistic Pleiotropy |

| Reproductive Timing Manipulation | Forcing reproduction at different ages or life stages | Earlier reproduction associated with reduced growth and shorter lifespan [7] | Temporal allocation decision has long-term somatic consequences |

| Resource Supplementation | Providing additional nutrition to reproducing individuals | Can partially mitigate but not eliminate reproductive costs [9] | Suggests both energetic and non-energetic (e.g., hormonal) mechanisms |

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive investigation into this trade-off integrates both field and laboratory approaches, as illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Approaches and Reagents

Research investigating the reproduction-somatic effort trade-off employs specialized methodological approaches and tools across field and laboratory settings.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Reproduction-Survival Trade-offs

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples/Assays | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Monitoring | Mark-recapture studies; Long-term individual monitoring; Life table construction | Quantifies age-specific survival and fecundity in natural populations | Essential for establishing correlations between reproductive effort and survival in wild populations [9] [13] |

| Experimental Manipulation | Brood/litter size manipulation; Resource supplementation; Hormone implants | Tests causality by directly altering reproductive investment or resource availability | Critical for demonstrating costs of reproduction rather than just correlations [9] |

| Physiological Assays | Oxidative stress markers (e.g., TBARS, protein carbonylation); Hormone assays (corticosterone, testosterone); Telomere length quantification | Measures physiological mechanisms mediating trade-offs | Links reproductive effort to cellular damage processes underlying senescence [9] |

| Laboratory Selection | Artificial selection for life history traits; Experimental evolution setups | Tests genetic basis of trade-offs and evolutionary trajectories | Demonstrates role of antagonistic pleiotropy; requires many generations [9] |

| Genetic Mapping | QTL analysis; Genome-wide association studies; Gene expression profiling | Identifies specific genetic loci involved in trade-offs | Molecular evidence for antagonistic pleiotropy [9] |

| Stable Isotopes | 13C, 15N labeling; Doubly-labeled water | Precisely tracks energy allocation to different functions | Quantifies energetic costs of reproduction versus somatic maintenance [9] |

| Junceellin | Junceellin, MF:C28H35ClO11, MW:583.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Bulleyanin | Bulleyanin, MF:C28H38O10, MW:534.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Contemporary Theoretical Debates and Future Directions

While the reproduction-somatic effort trade-off remains central to life history theory, recent evidence has challenged the universality of energy allocation as the sole explanatory mechanism [9]. Some studies have successfully uncoupled reproduction and longevity under specific conditions, suggesting additional explanatory frameworks are needed [9].

An emerging perspective proposes that ageing and associated trade-offs may result from suboptimal gene expression in late life rather than purely energetic constraints [9]. This "developmental theory of ageing" suggests that biological processes optimized for early-life function become maladaptive when they persist unabated in late life, with natural selection being too weak to optimize post-reproductive regulation [9]. Future research should aim to integrate energy allocation perspectives with these newer frameworks that consider information deterioration and regulatory network failures as complementary drivers of senescence [9].

Recent work in human evolution has applied these principles to explain distinctive human traits, particularly extended post-reproductive lifespans. The grandmother hypothesis suggests that somatic maintenance into post-reproductive years was selected because grandmothers' efforts enhanced their inclusive fitness by supporting the reproduction of their children and survival of their grandchildren [14]. This represents a unique evolutionary solution to the reproduction-somatic effort trade-off in humans, where somatic maintenance extends beyond the reproductive period but still provides fitness benefits.

Within life history theory, the fast-slow continuum represents a fundamental framework for understanding how organisms allocate metabolic resources to survival, growth, and reproduction in response to ecological pressures. This in-depth technical guide examines the precise mechanisms through which environmental harshness and unpredictability drive the development of faster life history strategies. We synthesize core theoretical principles with empirical data, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of adaptive responses to environmental challenge. The article includes quantitative summaries, experimental protocols for key studies, and visualizations of strategic trade-offs to serve as a foundational resource for ongoing research in behavioral ecology and related disciplines.

Life history theory is a branch of evolutionary ecology that explains how natural selection shapes organisms to optimize their survival and reproduction in the face of ecological challenges [15]. It analyzes the evolution of fitness components, known as life history traits, which include age and size at maturity, number and size of offspring, reproductive effort, and lifespan [15]. The central problem of life history evolution is an optimization problem: given particular ecological factors affecting survival and reproduction, and given intrinsic constraints and trade-offs, what are the optimal combinations of life history traits that maximize fitness? [15]

The fast-slow continuum is a pivotal concept within this framework. "Fast" strategies are characterized by early maturation, high reproductive output, and shorter lifespans, while "slow" strategies feature delayed maturation, fewer offspring, and extended longevity [16]. These strategies represent alternative solutions to the fundamental challenge of resource allocation, where organisms must partition finite metabolic energy among competing functions such as growth, maintenance, and reproduction [15]. This can be conceptualized as a finite pie, where making one slice larger necessarily makes another smaller [15]. Environmental conditions serve as the primary selective pressure determining where a population falls along this fast-slow continuum.

Defining the Environmental Drivers: Harshness and Unpredictability

Environmental pressures that shape life history strategies can be categorized into two primary dimensions: harshness and unpredictability. Understanding their distinct mechanisms is crucial for experimental design and interpretation.

Environmental Harshness

Environmental harshness refers to conditions that reduce age-specific survival rates or impair an organism's ability to extract energy from the environment. In highly harsh environments, the extrinsic mortality rate—the risk of death from unavoidable environmental factors—is elevated. This creates a selective pressure for faster life histories because the expected future reproductive value is diminished. When the probability of surviving to future reproductive events is low, natural selection favors individuals who mature earlier and allocate more resources to immediate reproduction rather than growth or maintenance [15].

Environmental Unpredictability

Environmental unpredictability describes temporal and spatial variation in resource availability or mortality risks that organisms cannot reliably anticipate through cues or learning. Unlike predictable seasonal changes, unpredictable fluctuations prevent organisms from developing adaptive phenotypic responses through plasticity. This uncertainty favors bet-hedging strategies that reduce variance in fitness at the expense of mean reproductive success. In unpredictable environments, faster strategies often emerge because they spread reproductive efforts across more frequent bouts, increasing the probability that at least some offspring encounter favorable conditions [17].

Quantitative Evidence from Cross-Cultural and Cross-Species Studies

Empirical evidence demonstrates clear relationships between environmental drivers and life history tempo. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from human foraging societies, illustrating how skill development and productivity peaks correlate with environmental pressures.

Table 1: Life History Skill Development in Human Foraging Societies [18]

| Population | Peak Skill Age (Years) | Skill Retention (>89% of max) | Key Environmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Average | 33 | Until age 56 | Composite of 40 sites worldwide |

| Matsigenka | 24 | Not specified | Tropical rainforest |

| Wola | 24 | Not specified | Papua New Guinea highlands |

| Aché | 37 | Not specified | Paraguayan subtropical forest |

| Valley Bisa | 45 | Slow decline | Zambian savanna |

Analysis of approximately 23,000 hunting records from more than 1,800 individuals across 40 locations reveals substantial variation in age-related productivity, with some societies exhibiting earlier peaks and others maintaining high skill levels throughout much of adulthood [18]. This heterogeneity reflects adaptation to local ecological conditions, including resource stability and mortality risks.

Table 2: Components of Individual Variation in Hunting Skill [18]

| Variation Type | Primary Source | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Within-site | Greater variation in rate of decline (m) than rate of increase (k) | Individual differences manifest more strongly later in life than during skill acquisition |

| Between-site | Roughly equal variation in rate of increase (k) and decline (m) | Ecological differences affect both development and maintenance of foraging competence |

| Correlation | Positive correlation between k and m | Hunters who develop skill quickly also tend to maintain it longer |

The finding that within-site variation depends more on heterogeneity in rates of skill decline than in rates of increase suggests that environmental pressures disproportionately affect the maintenance of competence rather than its acquisition [18].

Physiological and Psychological Mechanisms

Metabolic Trade-Offs and Resource Allocation

At the physiological level, faster strategies emerge from competitive allocation of limited resources to reproduction at the expense of maintenance and growth [15]. This trade-off is quantified through the Euler-Lotka equation, which describes population growth rate (fitness) as a function of age-specific survival and reproduction [15]. In harsh environments where extrinsic mortality is high, the fitness returns from investing in somatic maintenance and delayed reproduction diminish, favoring reallocation to earlier and more frequent reproductive bouts.

Predictive Adaptive Responses and Developmental Plasticity

Organisms may use early-life environmental cues to develop phenotypes matched to expected future conditions—a process known as predictive adaptive responses. When early environments signal high harshness or unpredictability, developmental trajectories shift toward faster strategies through mechanisms such as accelerated sexual maturation, reduced parental investment per offspring, and heightened stress responsiveness [17]. These plastic responses represent adaptive adjustments to ecological challenges, though mismatches between early cues and later environments can produce maladaptive outcomes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Quantifying Life History Traits in Natural Populations

Objective: To measure key life history traits and relate them to environmental harshness and unpredictability.

Field Methods:

- Demographic Monitoring: Mark and recapture individuals across multiple generations to construct age-specific survival curves (lx) and fecundity schedules (mx).

- Environmental Assessment: Quantify harshness via extrinsic mortality rates (predation pressure, climatic extremes) and unpredictability via temporal variance in resource availability.

- Reproductive Timing: Record age and size at first reproduction through direct observation or morphological indicators of sexual maturity.

- Reproductive Allocation: Measure offspring number, size, and investment through nest monitoring, litter counts, or longitudinal reproductive histories.

Analytical Framework:

- Calculate population growth rate (r) using the Euler-Lotka equation: ∑e^(-rx)lxmx = 1 [15]

- For stable populations, use net reproductive rate: R0 = ∑lxm_x [15]

- Construct reaction norms to assess plastic responses to environmental gradients

Protocol: Cross-Cultural Analysis of Human Foraging Efficiency

Objective: To document age-related patterns of skill development and decline across diverse subsistence societies [18].

Field Methods:

- Harvest Recording: Document individual hunting returns (mass, encounter rate) with associated hunter age.

- Skill Assessment: Quantify proficiency through standardizable measures (kg/hour, success rate).

- Environmental Covariates: Measure ecological variables potentially influencing skill acquisition and expression.

Statistical Modeling:

- Fit hierarchical Bayesian models to estimate age-productivity curves

- Partition variance into within-site and between-site components

- Model skill function as dependent on rates of increase (k) and decline (m) parameters [18]

Visualizing Strategic Pathways and Trade-Offs

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway through which environmental drivers shape life history strategies through perceived mortality risks and resource allocation decisions:

Figure 1: Environmental drivers and their pathways to faster life history strategies

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental trade-offs in resource allocation that underlie life history strategy evolution:

Figure 2: Resource allocation trade-offs underlying life history strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodologies and Analytical Tools for Life History Research

| Tool/Method | Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mark-Recapture Protocols | Demographic monitoring | Estimate age-specific survival rates (lx) in wild populations |

| Euler-Lotka Equation | Fitness calculation | Calculate population growth rate (r) from life table data [15] |

| Quantitative Genetic Breeding Designs | Trade-off analysis | Estimate genetic correlations and heritability of life history traits [15] |

| Stable Isotope Analysis | Physiological assessment | Trace resource allocation patterns and environmental responses [17] |

| Hierarchical Bayesian Models | Cross-population analysis | Partition variance within and between populations while quantifying uncertainty [18] |

| Agent-Based Models (ABMs) | Theoretical exploration | Simulate individual decision-making and emergent life history patterns [17] |

| Epithienamycin B | Epithienamycin B, CAS:65376-20-7, MF:C13H16N2O5S, MW:312.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sophoraflavanone H | Sophoraflavanone H, MF:C34H30O9, MW:582.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Understanding how environmental harshness and unpredictability shape faster life history strategies provides crucial insights for behavioral ecology, conservation biology, and even drug development. For researchers developing interventions that may affect metabolic trade-offs or stress responsiveness, recognizing these evolved adaptive responses is essential. The quantitative frameworks, experimental protocols, and visual models presented here offer a foundation for investigating how ecological pressures drive strategic diversification across the tree of life.

Future research should focus on linking specific molecular pathways to life history trade-offs, particularly those involving resource allocation decisions. For drug development professionals, recognizing that many physiological systems are constrained by evolutionary trade-offs may inform therapeutic strategies that work with, rather than against, these deeply conserved biological principles.

The Concept of Darwinian Fitness and the 'Darwinian Demon' in Life History Modeling

This technical guide examines the core principles of Darwinian fitness and its operationalization in life history theory, with a specific focus on the conceptual tool of the "Darwinian Demon." We explore the mathematical frameworks for quantifying fitness, the fundamental life history trade-offs that constrain evolutionary optimization, and the experimental methodologies employed in behavioral ecology research. Designed for researchers and scientists, this review integrates theoretical models with empirical approaches, providing both conceptual clarity and practical methodological guidance for investigating evolutionary strategies in biological systems.

Darwinian fitness represents a foundational concept in evolutionary biology, defined as the relative reproductive success of an individual organism or genotype in a given environment [19]. Contrary to colloquial understandings of physical fitness, Darwinian fitness specifically quantifies an organism's capacity to pass its genes to subsequent generations [19]. This concept is central to understanding natural selection, as individuals with higher fitness are more likely to survive, reproduce, and thereby spread advantageous traits throughout a population over time [19].

The interpretation of fitness as a propensity rather than a deterministic outcome is crucial in modern evolutionary theory [19]. This probabilistic framework acknowledges that fitness represents a natural tendency or predisposition for certain phenotypes to outperform others in reproductive output, accounting for environmental stochasticity and uncertainty in reproductive outcomes [19]. This perspective has evolved from classical deterministic models to more sophisticated frameworks that incorporate both population size constraints and random fluctuations in individual birth and death rates [20].

Within life history theory, fitness provides the ultimate currency for evaluating how organisms allocate limited resources among competing life functions—growth, maintenance, and reproduction—across their lifespan [21]. The concept of inclusive fitness further expands this framework by incorporating both an individual's own reproduction (Darwinian fitness) and the reproduction of genetic relatives (indirect fitness), establishing the principle of kin selection [21].

Quantifying Fitness: Mathematical Frameworks

The measurement of Darwinian fitness varies significantly between asexual and sexual organisms, with corresponding implications for research methodology and experimental design.

Absolute and Relative Fitness

Researchers typically employ two complementary metrics for quantifying fitness:

Absolute Fitness (W): The raw number of offspring produced by an individual genotype over one generation in asexual organisms, or the proportional change in genotype abundance due to selection [19]. This measure provides an unstandardized count of reproductive output.

Relative Fitness (w): A comparative measure calculated as the ratio of the absolute fitness of a genotype to the absolute fitness of a reference genotype (typically the most successful variant in the population) [19]. Relative fitness provides a standardized value where the fittest genotype equals 1, enabling direct comparisons across different populations or environmental conditions.

Table 1: Calculation of Relative Fitness in a Hypothetical Asexual Population

| Genotype | Absolute Fitness | Relative Fitness |

|---|---|---|

| AA | 20 | 1.00 |

| Aa | 10 | 0.50 |

| aa | 5 | 0.25 |

Fitness Calculations in Sexual Populations

For sexual organisms with Mendelian inheritance, fitness calculations incorporate genotype frequencies and follow more complex population genetic principles:

Table 2: Fitness Calculation for a Sexual Fly Population

| Genotype | Average Offspring | Relative Fitness |

|---|---|---|

| Aâ‚Aâ‚ | 23 | 0.8214 |

| Aâ‚Aâ‚‚ | 26 | 0.9286 |

| Aâ‚‚Aâ‚‚ | 28 | 1.0000 |

The change in genotype frequencies due to selection can be modeled using the formula:

p²wâ‚â‚ + 2pqwâ‚â‚‚ + q²wâ‚‚â‚‚

Where p and q represent allele frequencies, and w denotes the relative fitness for each genotype [19]. This approach allows researchers to predict evolutionary trajectories under specific selective pressures.

Alternative Fitness Metrics

Classical models emphasized the Malthusian parameter (population growth rate) as the primary determinant of competitive outcomes [20]. However, recent analytical studies using diffusion processes demonstrate that this parameter only predicts invasion success in infinite populations [20]. In finite populations, competitive outcome becomes a stochastic process contingent on resource constraints, better characterized by evolutionary entropy—a measure of a population's rate of return to steady state after perturbation [20].

Life History Theory and Trade-Offs

Life history theory conceptualizes the developmental course of an organism's lifespan as the outcome of strategic trade-offs between investments in somatic effort (growth and development) and reproductive effort (mating and parenting) [21]. This framework interprets organisms as reproductive strategists that constantly allocate limited resources to optimize fitness [21].

Fundamental Life History Trade-Offs

The following diagram illustrates the key trade-offs that constrain the evolution of life history strategies:

These trade-offs manifest differently across developmental stages, with evolutionary selection pressure being strongest during prereproductive and reproductive phases, and diminishing in the postreproductive period [21]. Empirical studies across diverse human populations have demonstrated that early resource availability and attachment formation influence psychological development, which in turn affects neurophysiological maturation and ultimately defines reproductive scheduling—including age at first birth, interbirth intervals, and parental investment patterns [21].

The Darwinian Demon: A Theoretical Extreme

The Darwinian demon represents a hypothetical organism that would evolve if no biological constraints existed [22]. Such an organism would simultaneously maximize all fitness components: it would reproduce immediately after birth, produce infinite offspring, and live indefinitely [22]. Though no such organism exists, this conceptual extreme serves as an important null model in life history theory, similar to the role of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in population genetics [23] [22].

Approximations of Darwinian Demons

Certain organisms approximate aspects of the Darwinian demon ideal, particularly species with exceptionally rapid growth rates and reproductive output relative to body size. Duckweeds (Lemnoidae), for instance, represent the most rapidly growing angiosperms in proportion to their body mass [23]. These aquatic monocotyledonous plants exhibit a highly reduced body plan and demonstrate extraordinary reproductive rates under ideal conditions [23].

The concept of a "Darwin-Wallace demon" has been proposed to recognize both founders of natural selection theory, acknowledging that under real-world environmental constraints, perfect demons cannot exist, though the concept remains valuable for understanding life history evolution [23].

Experimental Methodologies in Life History Research

Protocol 1: Fitness Assay in Asexual Populations

Objective: Quantify absolute and relative fitness in asexually reproducing organisms under controlled laboratory conditions.

Materials and Methods:

- Establish isogenic lines of the study organism

- Maintain populations in standardized environmental conditions (temperature, light, nutrient availability)

- Conduct longitudinal monitoring of population size and reproductive output

- Count offspring produced per individual over a defined generational timeframe

- Calculate absolute fitness as mean offspring number per genotype

- Compute relative fitness by normalizing to the highest-performing genotype

Data Analysis:

Protocol 2: Genotype Frequency Tracking in Sexual Populations

Objective: Document changes in genotype frequencies across generations to infer fitness differences.

Materials and Methods:

- Establish breeding populations with known initial genotype frequencies

- Implement controlled breeding design with tracking of parental genotypes

- Genotype offspring to establish actual inheritance patterns

- Record number of offspring produced by each breeding pair

- Track genotype frequencies across multiple generations

- Calculate relative fitness using genotype frequency changes

Validation: Compare observed frequency changes to predictions based on Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium modified by selection coefficients [19].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Materials for Life History Fitness Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Isogenic Lines | Establish genetically uniform starting material for fitness comparisons | Ensure sufficient replication to account for residual variation |

| Environmental Chambers | Maintain standardized abiotic conditions during experiments | Precisely control temperature, humidity, photoperiod, and nutrient availability |

| Genotyping Platform | Determine genotype frequencies in sexual populations | Select appropriate markers (SNPs, microsatellites) based on study organism |

| Population Cages | Maintain populations under controlled density conditions | Design appropriate size to prevent unnatural crowding effects |

| Demographic Monitoring System | Track birth, death, and reproductive events in real-time | Automated systems reduce observer bias and increase data resolution |

| Nutrient Media | Standardize nutritional environment across treatments | Formulate to mimic natural conditions while allowing experimental manipulation |

| AH13 | AH13, MF:C34H30O8, MW:566.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ophiopojaponin C | Ophiopojaponin C, MF:C46H72O17, MW:897.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Current Research Directions and Conceptual Challenges

Contemporary research in Darwinian fitness estimation has moved beyond classical Malthusian parameters to incorporate more sophisticated measures including evolutionary entropy, which accounts for population stability and robustness [20]. Computational and numerical analyses increasingly reject simple Malthusian models in favor of entropic principles that better predict stochastic competitive outcomes in finite populations [20].

The integration of fitness landscapes with life history trade-offs continues to present conceptual challenges, particularly in understanding how multiple constraints interact to shape evolutionary trajectories. Recent work on organisms that approximate Darwinian demons, such as duckweeds and social insects, reveals the complex interplay between physiological constraints, ecological pressures, and genetic architectures that prevent the evolution of truly demonic life histories [23] [22].

Future research directions include developing more comprehensive models that integrate fitness measures across temporal scales, better incorporating stochastic environmental variation into fitness predictions, and understanding how life history trade-offs manifest at molecular and physiological levels. These advances will enhance our ability to predict evolutionary responses to rapid environmental change and inform conservation strategies, agricultural practices, and understanding of disease evolution.

From Theory to Practice: Modeling Strategies and Applications in Human Health

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is a powerful, multivariate statistical technique that enables researchers to test and evaluate complex networks of causal relationships. In ecological and behavioral studies, SEM has become an indispensable method for testing hypotheses involving multiple variables and their direct and indirect effects. SEM differs fundamentally from other modeling approaches as it explicitly tests pre-assumed causal relationships based on a strong theoretical foundation. The method has evolved through three generations, beginning with Wright's development of path analysis (1918-1921), progressing through integration with factor analysis in social sciences, and culminating in the modern era with Judea Pearl's structural causal model and the integration of Bayesian modeling. [24]

In life-history theory research, SEM provides a robust framework for understanding how organisms allocate limited bioenergetic and material resources between somatic effort (resources devoted to continued survival) and reproductive effort (resources devoted to mating and parenting). These allocation patterns represent life-history strategies that exist along a fast-slow continuum. Fast life-history strategists prioritize current reproduction over future reproduction, investing less in somatic maintenance, while slow life-history strategists devote more time and energy to growth and maintaining long-term health. The application of SEM allows researchers to model how environmental factors, childhood experiences, and current conditions shape these strategic trade-offs and their behavioral manifestations. [25]

Theoretical Foundations: Life History Theory

Core Principles of Life History Theory

Life History (LH) theory addresses the fundamental trade-offs involved in allocating finite time, energy, and resources across an organism's lifespan. All living organisms face the challenge of optimizing resource allocation among competing functions necessary for survival and reproduction. These trade-offs are influenced by local environmental conditions and an organism's intrinsic constraints. According to LH theory, individuals calibrate their strategies in response to cues about environmental conditions, with critical ecological signals including both intrinsic and extrinsic mortality risks. Extrinsic mortality refers to death risk from external factors equally shared by population members, while intrinsic mortality results from an individual's specific resource allocation decisions. [25]

The fast-slow continuum of life-history strategies represents a central framework for understanding individual differences in behavioral and psychological traits. Faster LH strategies typically emerge in response to harsh, threatening, and resource-limited environments characterized by high morbidity and mortality. These strategies orient toward immediate survival goals and are associated with traits such as greater risk-taking propensity, impulsivity, and present-oriented time preferences. In contrast, slower LH strategies are more common in stable, less threatening, and resource-rich environments, favoring long-term planning, delayed gratification, and investment in somatic maintenance. [25]

Measurement and Manifestation of Life History Traits

Life-history strategies manifest through coordinated patterns in physiological, behavioral, and psychological traits. In human research, LH theory encompasses not only classical traits such as timing of maturation and reproduction but also psychological variables including risk attitudes, ability to delay gratification, prosociality, religiosity, and optimism. Researchers have identified clusters of behavioral and psychological correlates associated with slow versus fast LH trajectories, with empirical data confirming that faster LH strategies are more likely in perilous, threatening, and resource-limited ecologies. [25]

Table 1: Key Life-History Trade-Offs and Their Manifestations

| Trade-Off Dimension | Fast Strategy Manifestation | Slow Strategy Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Timing | Early maturation and reproduction | Delayed maturation and reproduction |

| Reproductive Investment | Many offspring with less parental investment | Fewer offspring with substantial parental investment |

| Somatic Effort | Reduced investment in long-term health | Substantial investment in growth and maintenance |

| Time Perspective | Present-oriented | Future-oriented |

| Risk Tolerance | Higher risk-taking propensity | Lower risk-taking propensity |

| Mating Orientation | Shorter-term mating orientation | Longer-term mating orientation |

Structural Equation Modeling Fundamentals

Core Components of SEM

SEM comprises two primary statistical methods: confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis, which originated in psychometrics, aims to estimate latent psychological traits such as attitudes and satisfaction. Path analysis, with its beginnings in biometrics, seeks to establish causal relationships among variables through path diagrams. The integration of these methods in the early 1970s created the modern SEM framework that has become popular across numerous scientific disciplines. [24]

SEM incorporates several types of variables with distinct functions:

- Observable variables: Directly measured indicators (e.g., age, weight, behavioral counts)

- Latent variables: Unobserved constructs derived from multiple indicators through factor analysis (e.g., "environmental harshness," "reproductive effort")

- Composite variables: Unobservable variables that are exact linear combinations of indicators with assumed no error variance

The SEM framework consists of two interconnected models: the measurement model, which defines how latent variables are measured by observable indicators, and the structural model, which tests all hypothesized dependencies based on path analysis. [24]

The SEM Process: A Five-Step Framework

Implementing SEM involves five logical steps that ensure methodological rigor:

Model Specification: Defining hypothesized relationships among variables based on theoretical knowledge and prior research. This step involves constructing a path diagram that represents the causal assumptions to be tested.

Model Identification: Determining whether the model is over-identified, just-identified, or under-identified. Model coefficients can only be estimated in just-identified or over-identified models.

Parameter Estimation: Using specialized estimation techniques (e.g., maximum likelihood, weighted least squares) to calculate model coefficients that best reproduce the observed covariance matrix.

Model Evaluation: Assessing model performance and fit using quantitative indices that measure how well the hypothesized model corresponds to the observed data.

Model Modification: Adjusting the model to improve fit when necessary, through post hoc modifications that are theoretically justifiable. [24]

Methodological Protocols for SEM in Life History Research

Experimental Design Considerations

Effective application of SEM in life-history research requires careful attention to research design and measurement. Sample size considerations are particularly important, as insufficient sample sizes can lead to convergence problems, improper solutions, and unstable parameter estimates. While absolute sample size requirements depend on model complexity, effect sizes, and data distributions, general guidelines suggest minimum sample sizes of 100-200 cases for models with few latent variables and strong indicators. [24]

Longitudinal designs are particularly valuable in life-history research, as they enable researchers to track developmental trajectories and causal sequences over time. The latent growth curve model, an SEM variant, allows for modeling individual differences in developmental patterns and testing predictors of these differences. For example, research on childhood ecological factors and their influence on adult psychosocial LH traits benefits from longitudinal data that captures developmental processes. [26]

Measurement Approaches for Life History Constructs

Measuring abstract life-history constructs requires careful attention to measurement validity and reliability. Latent variables such as "environmental harshness," "mating effort," or "somatic investment" must be operationalized through multiple observable indicators that capture different facets of the construct. For instance, in a study examining childhood ecology and adult psychosocial traits, researchers measured a "disordered microsystem" latent variable using indicators of childhood trauma, parental disengagement, parental cohabitation with an unrelated adult, and neighborhood crime. [26]

Confirmatory factor analysis provides the methodological foundation for establishing measurement models for latent life-history constructs. CFA extracts latent variables based on the correlated variations in the dataset, allowing researchers to account for measurement error, standardize scales across multiple indicators, and reduce data dimensionality. The application of CFA requires strong theoretical justification for the selection of indicators for each latent variable. [24]

Table 2: Example Measurement Model for Life-History Constructs

| Latent Variable | Indicator Variables | Measurement Source | Expected Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Harshness | Childhood socioeconomic status, Neighborhood crime rates, Parental investment | Self-report, Census data, Behavioral observation | 0.65-0.85 |

| Fast Life History Strategy | Impulsivity, Risk-taking, Short-term mating orientation, Present time perspective | Standardized scales, Behavioral tasks, Demographic history | 0.60-0.80 |

| Reproductive Effort | Number of sexual partners, Age at first reproduction, Mating investment | Life history calendar, Self-report | 0.70-0.90 |

| Somatic Effort | Health behaviors, Educational investment, Delayed gratification | Behavioral measures, Administrative records, Experimental tasks | 0.65-0.85 |

Analytical Procedures and Model Estimation

SEM estimation employs several statistical techniques, with maximum likelihood being the most common. The estimation process iteratively adjusts model parameters to minimize the discrepancy between the sample covariance matrix and the model-implied covariance matrix. Researchers must assess whether their data meet the assumptions of their chosen estimation method, including multivariate normality, absence of outliers, and sufficient sample size. [24]

For complex life-history models with categorical variables, non-normal distributions, or missing data, alternative estimation methods such as weighted least squares or Bayesian estimation may be more appropriate. Bayesian SEM is particularly valuable for complex models with limited sample sizes, as it incorporates prior knowledge through informative priors and provides more intuitive probability-based interpretations for parameters. [24]

Applications in Life History Research: Case Studies

Childhood Environment and Adult Life History Strategies

A compelling application of SEM in life-history research examined how childhood ecology before age 10 predicts adult psychosocial LH traits and mating effort. In this study, college women (N = 875) completed an online Qualtrics survey assessing childhood experiences and adult outcomes. SEM analysis revealed that faster life history psychosocial traits explained 22.2% of the relationship between the childhood microsystem and mating effort. Specifically, women who experienced a disordered microsystem (characterized by childhood trauma, parental disengagement, parental cohabitation with an unrelated adult, and neighborhood crime) were more likely to exhibit adult faster LH personality traits including psychopathy, impulsivity, resource control tendencies, and neuroticism. These personality traits subsequently predicted a greater number of lifetime sexual partners, shorter-term mating orientation, and greater intention to engage in risky sexual behaviors. [26]

The methodological approach in this study exemplifies strong SEM practice in life-history research. Researchers used multiple indicators to measure latent constructs, employed appropriate statistical controls, and tested a theoretically-grounded mediation model that connected early environmental conditions to adult outcomes through developmental mechanisms.

Quantitative Genetic Applications in Non-Human Species

SEM applications extend beyond human research to quantitative genetic studies of life-history traits in non-human species. Research on bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) populations demonstrated how SEM can elucidate the genetic architecture of life-history traits. Researchers estimated heritabilities of several life-history traits (longevity, age and mass at primiparity, and reproductive traits) and computed both phenotypic (rP) and genetic (rA) correlations between traits. Contrary to theoretical predictions of low heritability for fitness-related traits, estimates in the Ram Mountain population ranged from 0.02 to 0.81 (mean of 0.52), with several significantly different from zero. The study found no phenotypic or genetic correlations suggesting trade-offs among life-history traits, possibly due to genetic variation in resource acquisition ability or novel environmental conditions during the study period. [27]

This research highlights the importance of quantitative genetic approaches in life-history research and demonstrates how SEM can test fundamental evolutionary hypotheses about genetic constraints and trade-offs.

Integrating Genetic and Demographic Data