Reinforcement Learning in Behavioral Ecology: Bridging Animal Behavior and Drug Discovery

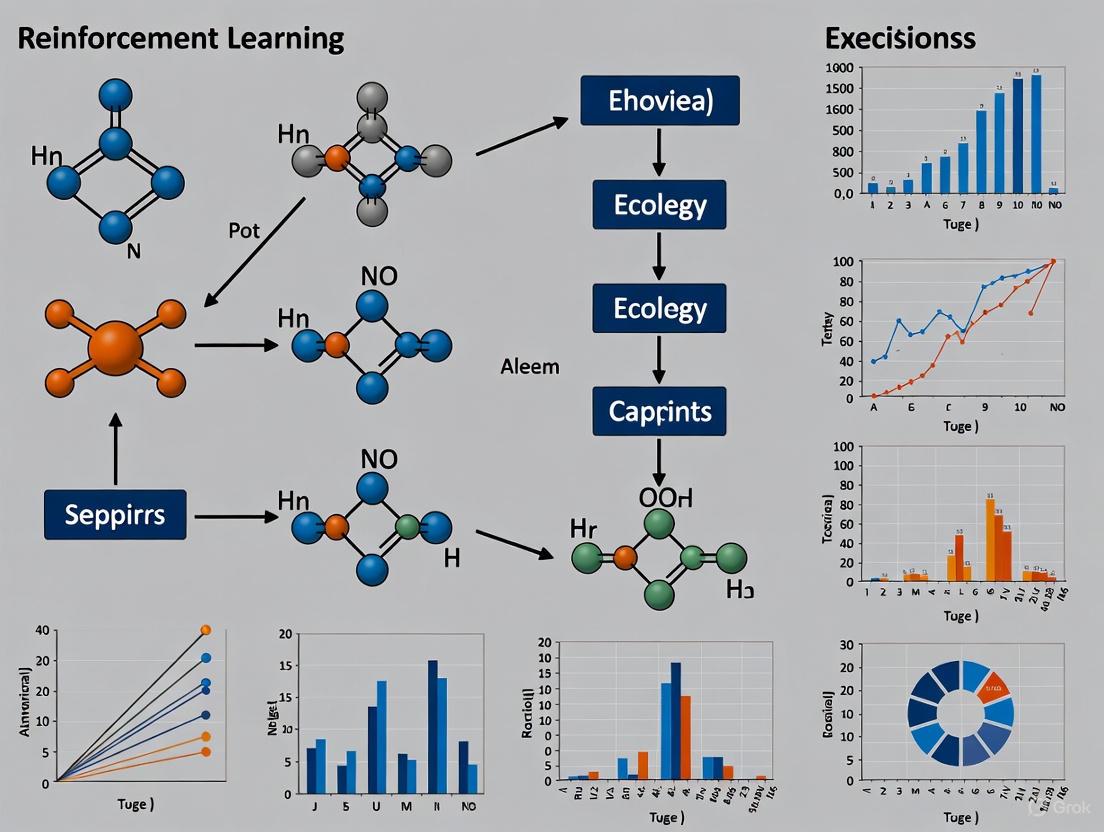

This article explores the transformative role of reinforcement learning (RL) methods in behavioral ecology and their translational potential for drug discovery.

Reinforcement Learning in Behavioral Ecology: Bridging Animal Behavior and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of reinforcement learning (RL) methods in behavioral ecology and their translational potential for drug discovery. It provides a foundational understanding of how RL models animal decision-making in complex, state-dependent environments, contrasting it with traditional dynamic programming. The piece details methodological applications, from analyzing behavioral flexibility in serial reversal learning to optimizing de novo molecular design. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as overcoming sparse reward problems in bioactive compound design, and covers validation through fitting RL models to behavioral data and experimental bioassay testing. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights RL as a pivotal tool for generating testable hypotheses in behavioral ecology and accelerating the development of novel therapeutic agents.

From Dynamic Programming to RL: A New Theoretical Framework for Animal Behavior

The Limitations of Traditional Dynamic Programming in Behavioral Ecology

Traditional dynamic programming (DP) has long been a cornerstone method for studying state-dependent decision problems in behavioral ecology, providing significant insights into animal behavior and life history strategies [1]. Its application is rooted in Bellman's principle of optimality, which ensures that a sequence of optimal choices consists of the optimal choice at each time step within a multistage process [1]. However, the increasing complexity of research questions in behavioral ecology has exposed critical limitations in the DP approach, particularly when dealing with highly complex environments, unknown state transitions, and the need to understand the biological mechanisms underlying learning and development [2]. This article explores these limitations and outlines how reinforcement learning (RL) methods serve as a powerful complementary framework, providing novel tools and perspectives for ecological research. We present quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and key research reagents to guide scientists in transitioning between these methodological paradigms.

Core Limitations of Traditional Dynamic Programming

The application of traditional DP in behavioral ecology is constrained by several foundational assumptions that often break down in realistic ecological scenarios. Table 1 summarizes the primary limitations and how RL methods address them.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Dynamic Programming and the Corresponding Reinforcement Learning Solutions

| Limiting Factor | Description of Limitation in Traditional DP | Reinforcement Learning Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model Assumptions | Requires perfect a priori knowledge of state transition probabilities and reward distributions, which is often unavailable for natural environments [2]. | Learns optimized policies directly from interaction with the environment, without needing an exact mathematical model [3]. |

| Problem Scalability | Becomes computationally infeasible (the "curse of dimensionality") for problems with very large state or action spaces [2]. | Uses function approximation and sampling to handle large or continuous state spaces that are infeasible for DP [3]. |

| Interpretation of Output | Output is often in the form of numerical tables, making characterization of optimal behavioral sequences difficult and sometimes impossible [1]. | The learning process itself can provide insight into the mechanisms of how adaptive behavior is acquired [2]. |

| Incorporating Learning & Development | Primarily suited for analyzing fixed, evolved strategies rather than plastic behaviors learned within an organism's lifetime [2]. | Well-suited to studying how simple rules perform in complex environments and the conditions under which learning is favored [2]. |

A central weakness of traditional DP is its reliance on complete environmental knowledge. As noted in behavioral research, DP methods "require that the modeler knows the transition and reward probabilities" [2]. In contrast, RL algorithms are designed to operate without this perfect information, learning optimal behavior through trial-and-error interactions, which is a more realistic paradigm for animals exploring an uncertain world [3].

Furthermore, the interpretability of DP outputs remains a significant challenge. The numerical results generated by DP models can be opaque, requiring "great care... in the interpretation of numerical values representing optimal behavioral sequences" and sometimes proving nearly impossible to decipher in complex models [1]. RL, particularly when combined with modern visualization techniques, can offer a more transparent view into the learning process and the resulting policy structure.

Quantitative Comparisons: DP vs. RL Performance

Recent empirical studies across multiple fields have quantified the performance differences between DP and RL approaches. Table 2 synthesizes findings from a dynamic pricing study, illustrating how data requirements influence the choice of method.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Data-Driven DP and RL in a Dynamic Pricing Market [4]

| Amount of Training Data | Performance of Data-Driven DP | Performance of RL Algorithms | Best Performing Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few Data (~10 episodes) | Highly competitive; achieves high rewards with limited data. | Learns from limited interaction; performance is still improving. | Data-Driven DP |

| Medium Data (~100 episodes) | Performance plateaus as it relies on estimated model dynamics. | Outperforms DP methods as it continues to learn better policies. | RL (PPO algorithm) |

| Large Data (~1000 episodes) | Limited by the accuracy of the initial model estimations. | Performs similarly to the best algorithms (e.g., TD3, DDPG, PPO, SAC), achieving >90% of the optimal solution. | RL |

The data in Table 2 highlights a critical trade-off. While well-understood DP methods can be superior when data is scarce, RL approaches unlock higher performance as more data becomes available, ultimately achieving near-optimal outcomes. This sample efficiency is a key consideration for researchers designing long-term behavioral studies.

Experimental Protocols for RL in Behavioral Ecology

Protocol: Two-Choice Operant Assay for Social vs. Non-Social Reward Seeking

This protocol details an automated, low-cost method to compare reward-seeking behaviors in mice, readily combinable with neural manipulations [5].

- Objective: To directly compare and quantify active social and nonsocial reward-seeking behavior, isolating the motivational component from consummatory behaviors.

- Materials and Assembly:

- Apparatus: An acrylic chamber with two reward access zones (social and sucrose) on opposite sides and two choice ports on an adjacent wall.

- Construction:

- On the chosen side of the acrylic box, mark and drill two 1-inch diameter holes for the choice ports using a graduated step drill bit. Smooth edges with a file.

- On an adjacent side, drill a 1-inch hole for the sucrose reward delivery port.

- On the opposite side, mark and cut a 2"x2" square for social target access using a hot knife (heated to 315°C) after creating pilot holes with a drill.

- Assemble the automated social gate by attaching a flat aluminum sheet to a camera slider's platform via an L-bracket. This gate, controlled by an Arduino Uno, will cover the social access square.

- Behavioral Experiment Procedure:

- Habituation: Acclimate the experimental mouse to the operant chamber.

- Training: Train the mouse to nose-poke at the choice ports to receive rewards.

- A nose-poke in the "social" port triggers the Arduino to retract the aluminum gate, allowing temporary access to a conspecific.

- A nose-poke in the "sucrose" port delivers a liquid sucrose reward.

- Testing: Conduct experimental sessions where the mouse is free to choose between the two ports. The number of pokes and rewards obtained for each option is automatically recorded by the software.

- Neural Manipulation (Optional): Combine the assay with optogenetics or fiber photometry to record or manipulate activity in specific neural circuits during decision-making.

Diagram: Two-Choice Operant Assay Workflow

Protocol: RL-Based Analysis of Species Coexistence with a Spatial RPS Game

This protocol employs a Q-learning framework to study the stable coexistence of species in a rock-paper-scissors (RPS) system, addressing a key ecological question [6].

- Objective: To model how adaptive movement behavior, governed by RL, can promote biodiversity in a system of cyclic competition, even under conditions where traditional models predict extinction.

- Model Setup:

- Environment: Create a spatial grid (e.g., 100x100) with periodic boundary conditions.

- Agents: Populate the grid with individuals from three species (A, B, C) following a cyclic dominance: A eliminates B, B eliminates C, C eliminates A.

- Processes: Define the following stochastic processes for each individual:

- Reproduction (Rate μ): An individual can reproduce into an adjacent empty site.

- Predation (Rate σ): An individual can eliminate a dominated neighbor species, freeing up the site.

- Migration (Rate ε₀): An individual can swap places with a neighbor (species or empty).

- Q-Learning Integration:

- State (s): For an individual, the state is defined by the types of neighbors (including empty sites) in its immediate vicinity.

- Action (a): The primary adaptive action is the decision to migrate or stay in the current location.

- Reward (r): Individuals receive positive rewards for eliminating prey (predation-priority) and negative rewards (or a high cost) for being eliminated. Surviving each time step may confer a small positive reward.

- Learning: Individuals of the same species share a common Q-table. They update their Q-values using the standard Q-learning update rule:

Q(s,a) ← Q(s,a) + α [r + γ maxₐ′ Q(s′,a′) - Q(s,a)], whereαis the learning rate andγis the discount factor.

- Execution and Analysis:

- Run the simulation for a sufficient number of time steps for the Q-tables to converge during a learning phase.

- In the subsequent evaluation phase, use the learned Q-tables to guide migration decisions.

- Track the population densities of all three species over time and compare the outcomes with a control model where mobility (ε₀) is fixed and non-adaptive.

- Analyze the emergent behavioral tendencies from the Q-tables, such as "survival-priority" (escaping predators) and "predation-priority" (remaining near prey).

Diagram: Q-Learning Cycle for an Individual Agent

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Customizable Operant Chamber | Provides a controlled environment for assessing active reward-seeking choices between social and nonsocial stimuli. | Two-Choice Operant Assay [5] |

| Automated Tracking Software | Quantifies locomotor endpoints (e.g., velocity, distance traveled) and behavioral patterns without subjective hand-scoring. | Behavioral Response Profiling in Larval Fish [7] |

| Arduino Uno Microcontroller | A low-cost, open-source platform for automating experimental apparatus components, such as gate movements and reward delivery. | Two-Choice Operant Assay [5] |

| Q-Learning Algorithm | A model-free RL algorithm that allows individuals to learn an action-value function, enabling adaptive behavior in complex spatial games. | Species Coexistence in Spatial RPS Model [6] |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | A state-of-the-art RL algorithm known for stable performance and sample efficiency, suitable for complex multi-agent environments. | Dynamic Pricing Market Comparison [4] |

The limitations of traditional dynamic programming—its reliance on perfect environmental models, poor scalability, and opaque outputs—present significant hurdles for advancing modern behavioral ecology. Reinforcement learning emerges not necessarily as a replacement, but as a powerful complementary framework that enriches the field. RL methods excel in complex environments with unknown dynamics and provide a principled way to study the learning processes and mechanistic rules that underpin adaptive behavior. The experimental protocols and tools detailed herein provide a concrete pathway for researchers to integrate RL into their work, offering new perspectives on enduring questions from decision-making and species coexistence to the very principles of learning and evolution.

Core Principles of Reinforcement Learning for State-Dependent Decision Problems

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a machine learning paradigm where an autonomous agent learns to make sequential decisions through trial-and-error interactions with a dynamic environment [8]. The agent's objective is to maximize a cumulative reward signal over time by learning which actions to take in various states [9]. This framework is particularly well-suited for state-dependent decision problems commonly encountered in behavioral ecology and drug development, where agents must adapt their behavior based on changing environmental conditions.

The foundation of RL is formally modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which provides a mathematical framework for modeling decision-making in situations where outcomes are partly random and partly under the control of the decision-maker [8]. An MDP is defined by key components that work together to create a learning system where agents can derive optimal behavior through experience.

Foundational Components of RL Frameworks

The following table summarizes the core components that constitute an RL framework for state-dependent decision problems:

Table 1: Core Components of Reinforcement Learning Frameworks

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in State-Dependent Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | s | The current situation or configuration of the environment [8] | Represents the decision context or environmental conditions the agent perceives |

| Action | a | A decision or movement the agent makes in response to a state [8] | The behavioral response available to the agent in a given state |

| Reward | r | Immediate feedback from the environment evaluating the action's quality [8] | Fitness payoff or immediate outcome of a behavioral decision |

| Policy | π | The agent's strategy mapping states to actions [8] | The behavioral strategy or decision rule the agent employs |

| Value Function | V(s) | Expected cumulative reward starting from a state and following a policy [8] | Long-term fitness expectation from a given environmental state |

| Q-function | Q(s,a) | Expected cumulative reward for taking action a in state s, then following policy π [8] | Expected long-term fitness of a specific behavior in a specific state |

These components interact within the MDP framework, where at each time step, the agent observes the current state s, selects an action a according to its policy π, receives a reward r, and transitions to a new state s' [8]. The fundamental goal is to find an optimal policy π* that maximizes the expected cumulative reward over time.

Algorithmic Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Key Algorithmic Methods

RL algorithms can be categorized into several approaches, each with distinct strengths for different problem types:

Table 2: Classification of Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Key Examples | Mechanism | Best Suited Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value-Based | Q-Learning, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) | Learns the value of state-action pairs (Q-values) and selects actions with highest values [9] [10] | Problems with discrete action spaces where value estimation is tractable |

| Policy-Based | Policy Gradient, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | Directly optimizes the policy function without maintaining value estimates [9] [11] | Continuous action spaces, stochastic policies, complex action dependencies |

| Actor-Critic | Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), A3C | Combines value function (critic) with policy learning (actor) for stabilized training [8] [11] | Problems requiring both sample efficiency and stable policy updates |

| Model-Based | MuZero, Dyna-Q | Learns an internal model of environment dynamics for planning and simulation [8] [9] | Data-efficient learning when environment models can be accurately learned |

Q-Learning Protocol for State-Dependent Decisions

Q-Learning stands as one of the most fundamental RL algorithms, operating through a systematic process of interaction and value updates [10]. The following protocol details its implementation:

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Q-Learning Implementation

| Step | Procedure | Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Environment Setup | Define state space, action space, reward function, and transition dynamics | States and actions should be discrete; reward function must appropriately capture goal [10] | In behavioral ecology, states could represent predator presence, energy levels; actions represent behavioral responses |

| 2. Q-Table Initialization | Create table with rows for each state and columns for each action | Initialize all Q-values to zero or small random values [10] | Tabular method limited by state space size; consider function approximation for large spaces |

| 3. Action Selection | Use ε-greedy policy: with probability ε select random action, otherwise select action with highest Q-value [10] | Start with ε=1.0 (full exploration), gradually decrease to ε=0.1 (mostly exploitation) | Exploration-exploitation balance critical; consider adaptive ε schedules based on learning progress |

| 4. Environment Interaction | Execute selected action, observe reward and next state | Record experience tuple (s, a, r, s') for learning [10] | Reward design crucial; sparse rewards may require shaping for effective learning |

| 5. Q-Value Update | Apply Q-learning update: Q(s,a) ← Q(s,a) + α[r + γmaxₐ⁻Q(s',a⁻) - Q(s,a)] | Learning rate α typically 0.1-0.5; discount factor γ typically 0.9-0.99 [10] | α controls learning speed; γ determines myopic (low γ) vs far-sighted (high γ) decision making |

| 6. Termination Check | Continue until episode termination or convergence | Convergence when Q-values stabilize between iterations [10] | In continuous tasks, use indefinite horizons with appropriate discounting |

The unique aspect of Q-Learning is its off-policy nature, where it learns the value of the optimal policy independently of the agent's actual actions [10]. The agent executes actions based on an exploratory policy (e.g., ε-greedy) while updating its estimates toward the optimal policy that always selects the action with the highest Q-value.

Deep Q-Network (DQN) Enhancement Protocol

For problems with large state spaces, Q-Learning can be enhanced with neural network function approximation:

Table 4: DQN Experimental Protocol

| Component | Implementation Details | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Network Architecture | Deep neural network that takes state as input, outputs Q-values for each action [8] | Handle high-dimensional state spaces (e.g., images, sensor data) |

| Experience Replay | Store experiences (s,a,r,s') in replay buffer, sample random minibatches for training [8] | Break temporal correlations, improve data efficiency |

| Target Network | Use separate target network with periodic updates for stable Q-value targets [8] | Stabilize training by reducing moving target problem |

| Reward Clipping | Constrain rewards to fixed range (e.g., -1, +1) | Normalize error gradients and improve stability |

Visualization of RL Workflows

Markov Decision Process Framework

MDP Interaction Loop

Q-Learning Algorithm Flow

Q-Learning Algorithm Flow

Deep Q-Network Architecture

Deep Q-Network Architecture

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of RL in research requires specific computational tools and frameworks:

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Reinforcement Learning Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RL Frameworks | TensorFlow Agents, Ray RLlib, PyTorch RL | Provide implemented algorithms, neural network architectures, and training utilities [8] | Accelerate development by offering pre-built, optimized components |

| Environment Interfaces | OpenAI Gym, Isaac Gym | Standardized environments for developing and testing RL algorithms [8] | Benchmark performance across different algorithms and problem domains |

| Simulation Platforms | NVIDIA Isaac Sim, Unity ML-Agents | High-fidelity simulators for training agents in complex, photo-realistic environments [9] | Safe training for robotics and autonomous systems before real-world deployment |

| Specialized Libraries | CleanRL, Stable Baselines3 | Optimized, well-tested implementations of key algorithms [8] | Research reproducibility and comparative studies |

| Distributed Computing | Apache Spark, Ray | Parallelize training across multiple nodes for faster experimentation [11] | Handle computationally intensive training for complex problems |

Application Protocols in Behavioral Ecology and Drug Development

Behavioral Ecology Application: Animal Foraging Strategy Optimization

Table 6: Protocol for Modeling Animal Foraging with RL

| Research Phase | Implementation Protocol | Ecological Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Formulation | Define state as (location, energylevel, timeofday, predatorrisk); actions as movement directions; reward as energy gain [9] | Habitat structure, resource distribution, predation risk landscape |

| Training Regimen | Train across multiple seasonal cycles with varying resource distributions; implement transfer learning between similar habitats [12] | Seasonal variation, resource depletion and renewal rates |

| Validation | Compare agent behavior with empirical field data; test generalization in novel environment configurations [12] | Trajectory patterns, patch residence times, giving-up densities |

Drug Development Application: Molecular Design Optimization

Table 7: Protocol for De Novo Drug Design with RL

| Research Phase | Implementation Protocol | Pharmacological Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Formulation | State: current molecular structure; Actions: add/remove/modify molecular fragments; Reward: weighted sum of drug-likeness, target affinity, and synthetic accessibility [13] [14] | QSAR models, physicochemical property predictions, binding affinity estimates |

| Model Architecture | Stack-augmented RNN as generative policy network; predictive model as critic [13] | SMILES string representation of molecules; property prediction models |

| Training Technique | Two-phase approach: supervised pre-training on known molecules, then RL fine-tuning with experience replay and reward shaping [14] | Chemical space coverage, multi-objective optimization of drug properties |

| Experimental Validation | Synthesize top-generated compounds; measure binding affinity and selectivity in vitro [14] | IC50, Ki, selectivity ratios, ADMET properties |

The ReLeaSE (Reinforcement Learning for Structural Evolution) method exemplifies this approach, integrating generative and predictive models where the generative model creates novel molecular structures and the predictive model evaluates their properties [13]. The reward function combines multiple objectives including target activity, drug-likeness, and novelty.

Advanced Technical Considerations

Addressing Sparse Reward Challenges

Many real-world applications in behavioral ecology and drug development face sparse reward challenges, where informative feedback is rare [14]. Several technical solutions have been developed:

Table 8: Techniques for Sparse Reward Problems

| Technique | Mechanism | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reward Shaping | Add intermediate rewards to guide learning toward desired behaviors [14] | Domain knowledge incorporation to create stepping stones to solution |

| Experience Replay | Store and replay successful trajectories to reinforce rare positive experiences [14] | Memory of past successes to prevent forgetting of valuable strategies |

| Intrinsic Motivation | Implement curiosity-driven exploration bonuses for novel or uncertain states [12] | Encourage systematic exploration of state space without external rewards |

| Hierarchical RL | Decompose complex tasks into simpler subtasks with their own reward signals [9] | Structured task decomposition to simplify credit assignment |

Transfer Learning Protocol for Ecological Applications

Adapting pre-trained policies to new environments is crucial for ecological validity:

Transfer Learning Protocol

This protocol enables policies learned in simulated environments to be transferred to real-world settings with minimal additional training, addressing the reality gap between simulation and field deployment [12].

The integration of evolutionary and developmental biology has revolutionized our understanding of phenotypic diversity, providing a mechanistic framework for investigating how fixed traits and plastic responses emerge across generations. This synthesis has profound implications for behavioral ecology research, particularly in conceptualizing adaptive behaviors through the lens of developmental selection processes. Evolutionary Developmental Biology (EDB) has revealed that developmental plasticity is not merely a noisy byproduct of genetics but a fundamental property of developmental systems that facilitates adaptation to environmental variation [15]. Within this framework, behavioral traits can be understood as products of evolutionary history that are realized through developmental processes sensitive to ecological contexts.

The core concepts linking evolution and development include developmental plasticity (the capacity of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions) and developmental selection (the within-organism sampling and selective retention of phenotypic variants during development) [16] [17]. These processes create phenotypic variation that serves as the substrate for evolutionary change, with developmental mechanisms either constraining or facilitating evolutionary trajectories. Understanding these interactions is particularly valuable for behavioral ecology research, where the focus extends beyond describing behaviors to explaining their origins, maintenance, and adaptive significance across environmental gradients.

Theoretical Framework: Plasticity and Developmental Selection

Forms of Behavioral Plasticity

Behavioral plasticity can be classified into two major types with distinct evolutionary implications [16]:

- Developmental Plasticity: The capacity of a genotype to adopt different developmental trajectories in different environments, resulting in relatively stable behavioral phenotypes. This form encompasses learning and any change in the nervous system that occurs during development in response to environmental triggers.

- Activational Plasticity: Differential activation of an underlying network in different environments such that an individual expresses various phenotypes throughout its lifetime without structural changes to the nervous system.

The classification of plasticity into these categories yields significant insights into their associated costs and consequences. Developmental plasticity, while potentially slower, produces a wider range of more integrated responses. Activational plasticity may carry greater neural costs because large networks must be maintained past initial sampling and learning phases [16].

Developmental Selection and Facilitated Variation

The theory of facilitated variation provides a conceptual framework for understanding how developmental processes generate viable phenotypic variation [17]. This perspective emphasizes that multicellular organisms rely on conserved core processes (e.g., transcription, microtubule assembly, synapse formation) that share two key properties:

- Exploratory behavior followed by somatic selection of the most functional state (e.g., random microtubule growth stabilized by signals; muscle precursor cell migration with selective retention of successfully innervated cells).

- Weak linkage where regulatory signals have easily altered relationships to specific developmental outcomes, enabling diverse inputs to produce diverse outputs through the same conserved machinery.

These properties allow developmental systems to generate functional phenotypic variation in response to environmental challenges without requiring genetic changes. Developmental selection refers specifically to the within-generation sampling of phenotypic variants and environmental feedback on which phenotypes work best [16]. This trial-and-error process during development enables immediate population shifts toward novel adaptive peaks and impacts the development of signals and preferences important in mate choice [16].

Quantitative Genetic Perspectives

From a quantitative genetics standpoint, traits influenced by developmental plasticity present unique challenges for evolutionary analysis [18]. The expression of quantitative behavioral traits depends on the cumulative action of many genes (polygenic inheritance) and environmental influences, with population differences not always reflecting genetic divergence. Heritability measures (broad-sense heritability = VG/VP; narrow-sense heritability = VA/VP) quantify the proportion of phenotypic variation attributable to genetic variation, with genotype-environment interactions complicating evolutionary predictions [18].

Table 1: Evolutionary Classification of Behavioral Plasticity

| Feature | Developmental Plasticity | Activational Plasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Different developmental trajectories triggered by environmental conditions | Differential activation of existing networks in different environments |

| Time Scale | Long-term, relatively stable | Short-term, reversible |

| Neural Basis | Changes in nervous system structure | Modulation of existing circuits |

| Costs | Sampling and selection during development | Maintenance of large neural networks |

| Evolutionary Role | Major shifts in adaptive peaks; diversification in novel environments | Fine-tuned adjustments to fine-grained environmental variation |

Application Notes: Experimental Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Quantitative Models for Evolutionary Analysis

The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process provides a powerful statistical framework for modeling the evolution of continuous traits, including behaviorally relevant gene expression patterns [19]. This model elegantly quantifies the contribution of both drift and selective pressure through the equation: dXt = σdBt + α(θ - Xt)dt, where:

- σ represents the rate of drift (modeled by Brownian motion)

- α parameterizes the strength of selective pressure driving expression back to an optimal level θ

- θ represents the optimal trait value

This approach allows researchers to distinguish between neutral evolution, stabilizing selection, and directional selection on phenotypic traits, enabling the identification of evolutionary constraints and lineage-specific adaptations [19]. Applications include quantifying the extent of stabilizing selection on behavioral traits, parameterizing optimal trait distributions, and detecting potentially maladaptive trait values in altered environments.

Reinforcement Learning as a Model for Developmental Selection

The integration of reinforcement learning (RL) frameworks provides a computational model for understanding developmental selection processes in behavioral ecology [15] [20]. RL algorithms, which optimize behavior through trial-and-error exploration and reward-based feedback, mirror how organisms sample phenotypic variants during development and retain those with the highest fitness payoffs.

Recent advances in differential evolution algorithms incorporating reinforcement learning (RLDE) demonstrate how adaptive parameter adjustment can overcome limitations of fixed strategies [20]. In these hybrid systems:

- The policy gradient network dynamically adjusts exploration-exploitation parameters

- Population classification enables differentiated strategies based on fitness

- Halton sequence initialization improves initial solution diversity

These computational approaches offer testable models for how developmental systems might balance stability and responsiveness to environmental variation through modular organization and regulatory connections [15].

Diagram 1: RL Model of Developmental Selection. This framework models how developmental processes explore phenotypic variants, receive environmental feedback, and update phenotypes through selection mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Developmental Plasticity in Behavioral Traits

Objective: To quantify developmental plasticity of predator-avoidance behavior in anuran tadpoles and identify the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic accommodation.

Background: Many anuran tadpoles develop alternative morphological and behavioral traits when exposed to predator kairomones during development [18]. This protocol adapts established approaches for manipulating developmental environments and tracking behavioral and neural consequences.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Developmental Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Composition | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predator Kairomone Extract | Chemical cues from predator species (e.g., dragonfly nymphs) dissolved in tank water | Induction of predator-responsive developmental pathways | Prepare fresh for each experiment; concentration must be standardized |

| Neuroplasticity Marker Antibodies | Anti-synaptophysin, Anti-PSD-95, Anti-BDNF | Labeling neural structural changes associated with behavioral plasticity | Use appropriate species-specific secondary antibodies |

| RNA Stabilization Solution | Commercial RNA preservation buffer (e.g., RNAlater) | Preservation of gene expression patterns at time of sampling | Immerse tissue samples immediately after dissection |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | Enzymes with differential activity based on methylation status (e.g., HpaII, MspI) | Epigenetic analysis of plasticity-related genes | Include appropriate controls for complete digestion |

Methodology:

Experimental Setup:

- Collect freshly laid eggs from a wild population or laboratory colony.

- Randomly assign eggs to three treatment groups upon reaching developmental stage Gosner 25:

- Control: Maintained in aged tap water

- Continuous Predator Cue: Maintained in water with predator kairomones

- Pulsed Predator Cue: Exposed to kairomones for 48-hour periods alternating with 48-hour control conditions

Behavioral Assays:

- At developmental stages Gosner 30, 35, and 40, transfer individual tadpoles to testing arenas.

- Record baseline activity for 10 minutes using automated tracking software.

- Introduce standardized visual or mechanical predator stimulus.

- Measure: (1) latency to freeze, (2) flight initiation distance, (3) shelter use, and (4) activity budget for 30 minutes post-stimulus.

Tissue Collection and Molecular Analysis:

- Euthanize subsets of tadpoles at each developmental stage following behavioral testing.

- Dissect and rapidly freeze brain tissues in liquid nitrogen.

- Perform RNA extraction and RNA-seq analysis to identify differentially expressed genes across treatments.

- Conduct reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) on genomic DNA to assess epigenetic modifications.

Data Analysis:

- Compare behavioral trajectories across development using multivariate ANOVA.

- Construct gene co-expression networks associated with behavioral phenotypes.

- Test for correlations between methylation status and behaviorally relevant gene expression.

Diagram 2: Developmental Plasticity Experimental Workflow. This protocol tests how varying temporal patterns of predator cue exposure shape behavioral development through molecular and neural mechanisms.

Protocol: Measuring Developmental Selection in Neural Circuit Formation

Objective: To quantify somatic selection processes during the development of sensory-motor integration circuits and test how experiential feedback shapes neural connectivity.

Background: Neural development often involves initial overproduction of synaptic connections followed by activity-dependent pruning—a clear example of developmental selection [17]. This protocol uses avian song learning as a model system to track how reinforcement shapes circuit formation.

Methodology:

Animal Model and Rearing Conditions:

- Use zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) males raised in controlled acoustic environments.

- Create three experimental groups:

- Normal Tutoring: Exposure to adult conspecific song during sensitive period

- White Noise Tutoring: Exposure to amplitude-matched white noise during sensitive period

- Isolation: Acoustic isolation during sensitive period

Neural Recording and Manipulation:

- Implant chronic recording electrodes in HVC and RA nuclei at 35 days post-hatching.

- Use miniature microdrives to track individual neurons across development.

- Employ optogenetic techniques to selectively inhibit specific neural populations during song practice.

Behavioral Reinforcement:

- Implement an automated system that detects song similarity to tutor template.

- Deliver auditory playbacks of tutor song contingent on specific song variants.

- Measure changes in neural activity and song structure following reinforcement.

Circuit Analysis:

- Use neural tracers (e.g., biocytin) to map connectivity changes.

- Perform confocal microscopy and reconstruction of dendritic arbors and spines.

- Conduct in situ hybridization for immediate early genes (e.g., ZENK) to identify actively reinforced circuits.

Analytical Approach:

- Apply network analysis to neural connectivity data to identify selection metrics.

- Use information theory to quantify how reinforcement shapes the development of neural codes.

- Model the developmental trajectory using reinforcement learning algorithms.

Integration with Biomedical Applications

Evolutionary Medicine and Drug Discovery

The principles linking evolution and development provide powerful insights for biomedical research, particularly in drug discovery [21] [22]. Evolutionary medicine applies ecological and evolutionary principles to understand disease vulnerability and resistance across species. This approach has revealed that:

- Many natural products with medicinal properties evolved as adaptive traits in response to ecological pressures rather than for human therapeutic use [22]

- Biomedical innovation can be accelerated by identifying animal models with natural resistance to human diseases through phylogenetic mapping [21]

- Understanding the original ecological functions of natural products can guide more efficient bioprospecting strategies [22]

Table 3: Evolutionary-Developmental Insights for Biomedical Applications

| Application Area | Evolutionary-Developmental Principle | Biomedical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Therapeutics | Somatic selection processes in tumor evolution | Adaptive therapy approaches that manage rather than eliminate resistant clones |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | Evolutionary arms races in host-pathogen systems | Phage therapy that targets bacterial resistance mechanisms |

| Neuropsychiatric Disorders | Developmental mismatch between evolved and modern environments | Lifestyle interventions that realign development with ancestral conditions |

| Drug Discovery | Natural products as evolved chemical defenses | Ecology-guided bioprospecting based on organismal defense systems |

Sustainable Bioprospecting Framework

Traditional bioprospecting approaches have high costs and low success rates, in part because they disregard the ecological context in which natural products evolved [22]. A more sustainable and efficient framework incorporates evolutionary-developmental principles by:

- Function-First Screening: Prioritizing compounds with demonstrated ecological roles (e.g., chemical defense, communication) before pharmacological testing

- Phylogenetic Targeting: Focusing on lineages with well-characterized evolutionary arms races or unique environmental challenges

- Conservation-Minded Collection: Using advanced analytical techniques (e.g., LC-MS/MS, GNPS molecular networking) that require minimal biomass

- Mechanistic Integration: Studying the developmental and genetic bases of compound production to enable sustainable production

This approach recognizes that natural products are fundamentally the result of adaptive chemistry shaped by evolutionary pressures, increasing the efficiency of identifying compounds with relevant bioactivities [22].

The integration of evolutionary and developmental perspectives provides a powerful framework for understanding the origins of behavioral diversity and its applications in biomedical research. By recognizing behavioral traits as products of evolutionary history mediated by developmental processes—including both fixed genetic programs and plastic responses to environmental variation—researchers can better predict how organisms respond to changing environments and identify evolutionary constraints on adaptation.

The concepts of developmental plasticity and developmental selection offer particularly valuable insights, revealing how phenotypic variation is generated during development and selected through environmental feedback. The experimental and analytical approaches outlined here—from quantitative genetic models to reinforcement learning frameworks—provide tools for investigating these processes across biological scales. As these integrative perspectives continue to mature, they promise to transform not only fundamental research in behavioral ecology but also applied fields including conservation biology, biomedical research, and drug discovery.

The Explore-Exploit Dilemma as a Central Concept in Behavioral Adaptation

The explore-exploit dilemma represents a fundamental decision-making challenge conserved across species, wherein organisms must balance the choice between exploiting familiar options of known value and exploring unfamiliar options of unknown value to maximize long-term reward [23]. This trade-off is rooted in behavioral ecology and foraging theory, providing a crucial framework for understanding behavioral adaptation across species, from rodents to humans [24]. The dilemma arises because exploiting known rewards ensures immediate payoff but may cause missed opportunities, while exploring uncertain options risks short-term loss for potential long-term gain [25]. In recent years, this framework has gained significant traction in computational psychiatry and neuroscience, offering a mechanistic approach to understanding decision-making processes that confer vulnerability for and maintain various forms of psychopathology [23].

Theoretical Foundations and Cognitive Mechanisms

Strategic Approaches to Resolution

Organisms employ several distinct strategies and heuristics to resolve the explore-exploit dilemma, each with different computational demands and adaptive values:

- Exploitation: Repeatedly sampling the option with the highest known value, requiring few cognitive resources and being adaptive after sufficient exploration or when cognitive resources are low [23].

- Directed Exploration: An information-seeking strategy biased toward options with the highest potential for information gain, often modeled with upper confidence bound algorithms [23].

- Random Exploration: Stochastic choice behavior where options are selected by chance, which can be value-free (completely random) or value-based (influenced by expected value and uncertainty) [23].

- Novelty Exploration: A simpler heuristic biased toward sampling unknown options, modeled with a novelty bonus parameter [23].

Computational Formulations

From a computational perspective, the explore-exploit dilemma can be conceptualized through several theoretical frameworks. The meta-control framework proposes that cognitive control can be cast as active inference over a hierarchy of timescales, where inference at higher levels controls inference at lower levels [25]. This approach introduces the concept of meta-control states that link higher-level beliefs with lower-level policy inference, with solutions to cognitive control dilemmas emerging through surprisal minimization at different hierarchy levels.

Alternatively, the signal-to-noise mechanism conceptualizes random exploration through a drift-diffusion model where behavioral variability is controlled by either the signal-to-noise ratio with which reward is encoded (drift rate) or the amount of information required before a decision is made (threshold) [26]. Research suggests that random exploration is primarily driven by changes in the signal-to-noise ratio rather than decision threshold adjustments [26].

Developmental and Sex-Specific Considerations

Research indicates that children and adolescents explore more than adults, with this developmental difference driven by heightened random exploration in youth [23]. With neural maturation and expanded cognitive resources, older adolescents rely more on directed exploration supplemented with exploration heuristics, similar to adults [23]. These developmental shifts coincide with the maturation of cognitive control and reward-processing brain networks implicated in explore-exploit decision-making [23].

Preclinical research suggests biological sex differences in exploration patterns, with male mice exploring more than female mice, while female mice learn more quickly from exploration than male mice [23]. Sex-specific maturation of the prefrontal cortex and dopaminergic circuits may underlie these differences, with potential implications for understanding vulnerability to psychopathology that predominantly affects females, including eating disorders [23].

Neural Substrates and Neurobiological Mechanisms

Dissociable Neural Networks

Research has identified dissociable neural substrates of exploitation and exploration in healthy adult humans:

- Exploitation Networks: Ventromedial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex activation has been consistently associated with exploitation behaviors [23].

- Exploration Networks: Anterior insula and prefrontal regions (frontopolar cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex) activation is associated with exploration [23].

- Strategy-Specific Pathways: Distinct neurobiological profiles underlie different exploration approaches, with random exploration associated with right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation, while directed exploration has been linked to right frontopolar cortex activation [23].

Neurochemical Modulators

Preliminary evidence suggests that different neuromodulatory systems may regulate distinct exploration strategies:

- Noradrenaline has been implicated in modulating random exploration [23].

- Dopamine has been associated with directed exploration [23].

- The dopaminergic system plays a crucial role in tracking recent reward trends and modulating novelty-seeking behavior during decision making [24].

Table 1: Neural Correlates of Explore-Exploit Decision Making

| Brain Region | Function | Associated Process |

|---|---|---|

| Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex | Value Representation | Exploitation |

| Orbitofrontal Cortex | Outcome Valuation | Exploitation |

| Frontopolar Cortex | Information Seeking | Directed Exploration |

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Cognitive Control | Random Exploration |

| Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Conflict Monitoring | Exploration |

| Anterior Insula | Uncertainty Processing | Exploration |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The Horizon Task: Cross-Species Paradigm

The Horizon Task is a widely used experimental paradigm that systematically manipulates time horizon to study explore-exploit decisions across species [27] [26]. The task involves a series of games lasting different numbers of trials, representing short and long time horizons.

Human Protocol

Apparatus and Setup: Computer-based implementation with two virtual slot machines (one-armed bandits) that deliver probabilistic rewards sampled from Gaussian distributions (truncated and rounded to integers between 1-100 points) [26].

Procedure:

- Instructed Trials: First four trials of each game are instructed, forcing participants to play specific options to control prior information [26].

- Information Manipulation: In "unequal" information conditions ([1 3] games), participants play one option once and the other three times, creating differential uncertainty. In "equal" information conditions ([2 2] games), both options are played twice [26].

- Horizon Manipulation: After instructed trials, participants make either 1 (short horizon) or 6 (long horizon) free choices [26].

- Task Conditions: Contrasting behavior between horizon conditions on the first free choice quantifies directed and random exploration [26].

Data Analysis:

- Directed Exploration: Measured as increased choice of the more informative option in long vs. short horizon conditions [26].

- Random Exploration: Measured as decreased choice predictability (lower slope of choice curves) in long vs. short horizon conditions [26].

- Computational Modeling: Logistic models incorporating reward difference (ΔR) and information difference (ΔI) parameters to quantify information bonus (A) and decision noise (σ) [26].

Rodent Protocol

Apparatus: Open-field circular maze (1.5m diameter) with eight equidistant peripheral feeders delivering sugar water (150μL/drop, 0.15g sugar/mL), each with blinking LED indicators [27].

Pretraining Phase:

- Light-Reward Association: Rats learn to associate blinking LEDs with reward availability [27].

- Guided Games: Rats run between home base and target feeders with rewards [27].

- Choice Introduction: Free-choice trials introduced after guided choices, beginning with 0 vs. 1 drop discrimination, progressing to 1 vs. 5 drops [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Choice Setup: Rats choose between two feeders with different reward probabilities [27].

- Information Control: One option has known reward size, the other unknown [27].

- Horizon Manipulation: Different numbers of choices per game represent short vs. long horizons [27].

- Behavioral Measures: Choice patterns, response latencies, and exploration strategies quantified across conditions [27].

Computational Analysis Methods

Drift-Diffusion Modeling

The drift-diffusion model (DDM) provides a computational framework for understanding the cognitive mechanisms underlying random exploration [26]:

Model Architecture:

- Evidence accumulation between two decision boundaries (explore vs. exploit)

- Drift rate (μ): Signal-to-noise ratio of reward value representations

- Decision threshold (β): Amount of information required before decision

- Starting point (x₀): Initial bias toward exploration or exploitation

Model Fitting: Parameters estimated from choice and response time data using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods, allowing separation of threshold changes from signal-to-noise ratio changes [26].

Hierarchical Active Inference Framework

This approach conceptualizes meta-control as probabilistic inference over a hierarchy of timescales [25]:

Implementation:

- Higher-level beliefs about contexts and meta-control states constrain prior beliefs about policies at lower levels

- Surprisal minimization drives arbitration between exploratory and exploitative choices

- Belief updating follows Bayesian principles with precision weighting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Explore-Exploit Investigations

| Item/Reagent | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Field Maze | Circular, 1.5m diameter, 8 peripheral feeders | Naturalistic rodent spatial decision-making environment |

| Sugar Water Reward | 150μL/drop, 0.15g sugar/mL concentration | Positive reinforcement for rodent behavioral tasks |

| LED Indicator System | Computer-controlled blinking LEDs | Cue presentation for reward availability |

| Horizon Task Software | Custom MATLAB or Python implementation | Presentation of bandit task with horizon manipulation |

| Drift-Diffusion Model | DDM implementation (e.g., HDDM, DMAT) | Computational modeling of decision processes |

| Eye Tracking System | Infrared pupil tracking (e.g., EyeLink) | Measurement of pupil diameter as proxy for arousal/exploration |

| fMRI-Compatible Response Device | Button boxes with millisecond precision | Neural recording during explore-exploit decisions |

Applications in Psychopathology and Drug Development

The explore-exploit framework provides novel insights into various psychiatric conditions and potential therapeutic approaches:

Eating Disorders

Suboptimal explore-exploit decision-making may promote disordered eating through several mechanisms [23]:

- Rigid exploitation of maladaptive eating patterns

- Reduced exploration of alternative behaviors

- Altered reward valuation of food choices

- Computational modeling can identify specific parameters contributing to pathological decision-making

Anxiety and Depression

Nascent research demonstrates relationships between explore-exploit patterns and internalizing disorders [23]:

- Anxious-depression symptoms correlate with novelty-based exploration patterns

- Intolerance of uncertainty may relate to specific exploration parameters, though evidence remains mixed [28]

- Altered arbitration between exploratory and exploitative control states in mood disorders

Substance Use Disorders

Explore-exploit paradigms offer novel approaches to understanding addiction [24]:

- Disrupted balance between goal-directed and habitual control

- Altered reward valuation and outcome prediction

- Enhanced exploitation of drug-related choices at expense of broader exploration

Therapeutic Implications

Understanding the neurobiological bases of explore-exploit decisions informs targeted interventions [23]:

- Neuromodulation approaches targeting specific prefrontal regions

- Pharmacological interventions modulating dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems

- Cognitive remediation targeting specific exploration deficits

- Computational psychiatry approaches for personalized treatment targeting

Visualizing Explore-Exploit Mechanisms

Decision Process Workflow

Neural Circuitry of Exploration Strategies

Experimental Protocol Flowchart

Future Directions and Methodological Considerations

Current Limitations and Challenges

Several methodological challenges remain in explore-exploit research:

- Species Comparisons: Direct cross-species comparisons are complicated by task differences and measurement limitations [27].

- Computational Modeling: Distinguishing between different exploration strategies requires sophisticated modeling approaches and careful task design [26].

- Neural Measurements: Linking specific exploration strategies to neural mechanisms remains challenging due to limitations in temporal and spatial resolution.

Emerging Research Frontiers

Promising research directions include:

- Cognitive Consistency Frameworks: Novel approaches that conduct pessimistic exploration and optimistic exploitation under reasonable premises to improve sample efficiency [29].

- Developmental Trajectories: Investigating how explore-exploit strategies evolve across the lifespan and relate to emergent psychopathology [23].

- Network Neuroscience Approaches: Understanding how distributed brain networks interact to regulate exploration-exploitation balance.

- Translational Applications: Developing targeted interventions for disorders characterized by explore-exploit imbalances.

The explore-exploit dilemma continues to provide a rich framework for understanding behavioral adaptation across species, with implications for basic neuroscience, clinical psychiatry, and drug development. By integrating computational modeling with sophisticated behavioral paradigms and neural measurements, researchers are progressively elucidating the mechanisms underlying this fundamental trade-off and its relevance to adaptive and maladaptive decision-making.

Methodological Integration and Cross-Disciplinary Applications

In behavioral ecology and neuroscience, behavioral flexibility—the ability to adapt behavior in response to changing environmental contingencies—is a crucial cognitive trait. Serial reversal learning experiments, where reward contingencies are repeatedly reversed, have long been a gold standard for studying this flexibility [30]. This Application Note details how Bayesian Reinforcement Learning (BRL) models provide a powerful quantitative framework for analyzing such learning experiments, moving beyond traditional performance metrics to uncover latent cognitive processes.

The integration of Bayesian methods with reinforcement learning offers principled approaches for incorporating prior knowledge and handling uncertainty [31]. When applied to behavioral data from serial reversal learning tasks, these models can disentangle the contributions of various cognitive components to behavioral flexibility, including learning rates, sensitivity to rewards, and exploration strategies. This approach is generating insights across fields from behavioral ecology [30] to developmental neuroscience [32] and drug development for cognitive disorders [33].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Key Model Parameters and Behavioral Metrics

Table 1: Core parameters of Bayesian Reinforcement Learning models in serial reversal learning studies

| Parameter | Description | Behavioral Interpretation | Measured Change in Grackles [30] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association-updating rate | Speed at which cue-reward associations are updated | How quickly new information replaces old beliefs | More than doubled by the end of serial reversals |

| Sensitivity parameter | Influence of learned associations on choice selection | Tendency to exploit known rewards versus explore alternatives | Declined by approximately one-third |

| Learning rate from negative outcomes | How much negative prediction errors drive learning | Adaptation speed after unexpected lack of reward | Closest to optimal in mid-teen adolescents [32] |

| Mental model parameters | Internal representations of environmental volatility | Beliefs about how stable or changeable the environment is | Most accurate in mid-teen adolescents during stochastic reversal [32] |

Table 2: Performance outcomes linked to model parameters

| Experimental Measure | Relationship to Model Parameters | Empirical Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Reversal learning speed | Positively correlated with higher association-updating rate | Faster reversals with increased updating rate [30] |

| Multi-option problem solving | Associated with extreme values of updating rates and sensitivities | Solved more options on puzzle box [30] |

| Performance in volatile environments | Dependent on learning rate from negative outcomes and mental models | Adolescent advantage in stochastic reversal tasks [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Serial Reversal Learning with Avian Subjects

Objective: To investigate the dynamics of behavioral flexibility in great-tailed grackles through serial reversal learning and quantify learning processes using Bayesian RL models [30].

Materials:

- Automated operant chambers with two choice cues

- Food rewards

- 19 wild-caught great-tailed grackles (or species of interest)

Procedure:

- Initial Discrimination:

- Present two visual cues (A and B)

- Reward selection of cue A (100% reinforcement)

- Continue until subject reaches pre-defined performance criterion

First Reversal:

- Switch contingency without warning

- Now only reward selection of cue B

- Continue until performance criterion is met

Serial Reversals:

- Repeat reversal procedure multiple times

- Maintain consistent performance criterion across reversals

- Counterbalance spatial position of correct cue

Data Collection:

- Record all choices and their outcomes

- Note trial-by-trial responses

- Document number of errors until criterion at each reversal

Protocol 2: Bayesian RL Model Fitting and Analysis

Objective: To estimate latent cognitive parameters from behavioral choice data [30] [32].

Materials:

- Choice data from Protocol 1

- Computational environment (Python, R, or MATLAB)

- Bayesian inference tools (Stan, PyMC3, or custom code)

Procedure:

- Model Specification:

- Define state space (cues, rewards, internal beliefs)

- Specify action space (choices available to subject)

- Formalize reward structure (positive/negative outcomes)

Parameter Estimation:

- Implement Bayesian inference methods

- Estimate posterior distributions for key parameters:

- Association-updating rate

- Sensitivity to learned associations

- Learning rates for positive/negative outcomes

- Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling or variational inference

Model Validation:

- Compare model predictions to actual choice behavior

- Perform posterior predictive checks

- Compare model variants using information criteria

Interpretation:

- Relate parameter changes to experimental manipulations

- Correlate individual parameter estimates with other cognitive measures

Visualizations

Serial Reversal Learning Experimental Workflow

Bayesian RL Modeling Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated operant chambers | Experimental apparatus | Present choice stimuli, deliver rewards, record responses | Serial reversal learning in grackles [30] |

| Bayesian RL modeling frameworks | Computational tool | Estimate latent cognitive parameters from choice data | Quantifying learning rates and sensitivity [30] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo samplers | Statistical software | Perform Bayesian parameter estimation | Posterior distribution estimation for model parameters [30] |

| Policy Gradient algorithms | Computational method | Solve sequential experimental design problems | Optimal design of experiments for model parameter estimation [34] |

| Stochastic reversal tasks | Behavioral paradigm | Assess flexibility in volatile environments | Studying adolescent cognitive development [32] |

Bayesian Reinforcement Learning models provide a powerful quantitative framework for analyzing behavioral flexibility in serial reversal learning paradigms. By moving beyond simple performance metrics to estimate latent cognitive parameters, these approaches reveal how learning processes themselves adapt through experience. The protocols and analyses detailed here enable researchers to bridge computational modeling with experimental behavioral ecology, offering insights into the dynamic mechanisms underlying behavioral adaptation across species and developmental stages.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in drug discovery represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical space, estimated to contain up to 10^60 drug-like molecules [35]. Among the most promising AI approaches are deep generative models, which can learn the underlying probability distribution of known chemical structures and generate novel molecules with desired properties de novo. A significant innovation in this field is the ReLeaSE (Reinforcement Learning for Structural Evolution) approach, which integrates deep learning and reinforcement learning (RL) for the automated design of bioactive compounds [13].

Framed within the broader context of behavioral ecology, ReLeaSE operates on principles analogous to adaptive behavior in biological systems. The generative model functions as an "organism" exploring the chemical environment, while the predictive model acts as a "selective pressure," rewarding behaviors (generated molecules) that enhance fitness (desired properties). This continuous interaction between agent and environment mirrors the fundamental processes of natural selection, providing a powerful framework for optimizing complex, dynamic systems.

The ReLeaSE Architecture: A Computational Framework

The ReLeaSE methodology employs a streamlined architecture built upon two deep neural networks: a generative model (G) and a predictive model (P). These models are trained in a two-phase process that combines supervised and reinforcement learning [13].

Molecular Representation and Encoding

ReLeaSE uses a simple representation of molecules as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line-Entry System) strings, a linear notation system that encodes the molecular structure as a sequence of characters [13] [35]. This representation allows the model to treat molecular generation as a sequence-generation task.

Table: Common Molecular String Representations

| Notation | Description | Key Feature | Example (Caffeine) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular Input Line-Entry System | Standard, widely-used notation | CN1C=NC2=C1C(=O)N(C(=O)N2C)C |

| SELFIES | SELF-referencing embedded Strings | Guarantees 100% molecular validity | [C][N][C][N][C]...[Ring1][Branch1_2] |

| DeepSMILES | Deep SMILES | Simplified syntax to reduce invalid outputs | CN1CNC2C1C(N(C(N2C)O)C)O |

For the model to process these strings, each character in the SMILES alphabet is converted into a numerical format, typically using one-hot encoding or learnable embeddings [35].

Neural Network Components

- Generative Model (G): This model is a generative Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), specifically a stack-augmented RNN (Stack-RNN). It is trained to produce chemically feasible SMILES strings one character at a time, effectively learning the syntactic and grammatical rules of the "chemical language" [13].

- Predictive Model (P): This is a deep neural network trained as a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model. It predicts the properties (e.g., biological activity, hydrophobicity) of a molecule based on its SMILES string [13] [14].

Diagram Title: ReLeaSE Two-Phase Training Architecture

Formalizing the RL Problem in Chemical Space

Within the ReLeaSE framework, the problem of molecular generation is formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), a cornerstone of RL theory that finds a parallel in modeling sequential decision-making in behavioral ecology.

MDP Formulation

The MDP is defined by the tuple (S, A, P, R), where [13]:

- State (S): All possible strings of characters from the SMILES alphabet, from length zero to a maximum length T. The state

s_0is the initial, empty string. - Action (A): The alphabet of all characters and symbols used to write canonical SMILES strings. Each action

a_tis the selection of the next character to add to the sequence. - Transition Probability (P): The probability

p(a_t | s_t)of taking actiona_tgiven the current states_tis determined by the generative model G. - Reward (R): A reward

r(s_T)is given only when a terminal states_T(a complete SMILES string) is reached. The reward is a function of the property predicted by the predictive model P:r(s_T) = f(P(s_T)). Intermediate rewards are zero.

Policy and Objective

The generative model G serves as the policy network π, defining the probability of each action given the current state. The goal of the RL phase is to find the optimal parameters Θ for this policy that maximize the expected reward J(Θ) from the generated molecules [13]. This is achieved using policy gradient methods, such as the REINFORCE algorithm [13] [36].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Core ReLeaSE Protocol

The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing the ReLeaSE method for a specific target property.

Objective: Train a ReLeaSE model to generate novel molecules optimized for a specific property (e.g., inhibitory activity against a protein target). Input: A large, diverse dataset of molecules (e.g., ChEMBL [14]) for pre-training, and a target-specific dataset with property data for training the predictive model.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Software | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Data | ChEMBL Database | Provides a large-scale, public source of bioactive molecules for pre-training the generative and predictive models. |

| Software/Library | Deep Learning Framework (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) | Provides the core environment for building, training, and deploying the deep neural networks (G and P). |

| Computational Method | Stack-Augmented RNN (Stack-RNN) | Serves as the architecture for the generative model, capable of learning complex, long-range dependencies in SMILES strings. |

| Computational Method | Random Forest / Deep Neural Network | Can be used as the predictive model architecture to forecast molecular properties from structural input. |

| Validation | Molecular Docking Software | Used for in silico validation of generated hits against a protein target structure (optional step). |

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Curate a dataset for pre-training the generative model, ensuring SMILES strings are canonicalized and valid.

- Prepare a separate, labeled dataset for the target property to train the predictive QSAR model.

Supervised Pre-training Phase:

- Train the Generative Model (G): Train the Stack-RNN on the general molecular dataset to predict the next character in a SMILES sequence. The objective is to maximize the likelihood of the training data, resulting in a model that can generate chemically valid molecules.

- Train the Predictive Model (P): Train the QSAR model (e.g., a Random Forest ensemble or a deep neural network) on the target-specific dataset to accurately predict the desired property from a SMILES string [14].

Reinforcement Learning Optimization Phase:

- Initialize: The pre-trained models G and P are integrated into the RL framework.

- Interaction Loop: For a predetermined number of episodes:

- The policy network (G) generates a batch of molecules by sequentially sampling characters, starting from the initial state

s_0. - For each completed molecule (terminal state

s_T), the predictive model (P) calculates the predicted property value. - A reward

r(s_T)is computed based on this prediction (e.g., high reward for high predicted activity). - The policy gradient is calculated, and the parameters of G are updated to maximize the expected reward. This biases the generator towards producing molecules with higher predicted property values.

- The policy network (G) generates a batch of molecules by sequentially sampling characters, starting from the initial state

Output: The optimized generative model is used to produce a focused library of novel molecules predicted to possess the desired property.

Addressing the Sparse Reward Challenge

A critical challenge in applying RL to de novo design is sparse rewards, where only a tiny fraction of randomly generated molecules show the desired bioactivity, providing limited learning signal [14]. The following technical innovations can significantly improve performance:

- Transfer Learning: Initializing the generative model with weights pre-trained on a large, diverse chemical database (like ChEMBL) provides a strong prior of chemical space, rather than starting from random initialization [14].

- Experience Replay: Storing high-scoring generated molecules in a buffer and replaying them during training reinforces successful strategies and stabilizes learning [14] [36].

- Reward Shaping: Designing the reward function to provide intermediate, heuristic rewards can guide the exploration more effectively than a single reward at the end of generation [14].

Diagram Title: Solutions for Sparse Reward Challenge

Proof-of-Concept Validation

In the foundational ReLeaSE study, the method was successfully applied to design inhibitors for Janus protein kinase 2 (JAK2) [13]. Furthermore, a related study that employed a similar RL pipeline enhanced with the aforementioned "bag of tricks" demonstrated the design of novel epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. Crucially, several of these computationally generated hits were procured and experimentally validated, confirming their potency in bioassays [14]. This prospective validation underscores the real-world applicability of the approach.

The performance of generative models like ReLeaSE can be evaluated against several key metrics, comparing its approach to other methodologies.

Table: Benchmarking Generative Model Performance

| Model / Approach | Key Innovation | Reported Application/Performance |

|---|---|---|

| ReLeaSE [13] | Integration of generative & predictive models with RL. | Designed JAK2 inhibitors; Generated libraries biased towards specific property ranges (e.g., melting point, logP). |

| REINVENT [14] | RL-based molecular generation. | Maximized predicted activity for HTR1A and DRD2 receptors. |

| RationaleRL [14] | Rationale-based generation for multi-property optimization. | Maximized predicted activity for GSK3β and JNK3 inhibitors. |

| Insilico Medicine (INS018_055) [37] | End-to-end AI-discovered drug candidate. | First AI-discovered drug to enter Phase 2 trials (Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis); Reduced development time to ~30 months and cost to one-tenth of traditional methods. |

The ReLeaSE approach exemplifies a powerful synergy between deep generative models and reinforcement learning, providing a robust and automated framework for de novo drug design. By conceptualizing molecular generation as an adaptive learning process, it efficiently navigates the immense complexity of chemical space. While challenges such as sparse rewards and the ultimate synthesizability of generated molecules remain active areas of research, the integration of techniques like transfer learning and experience replay has proven highly effective. As both AI methodologies and biological understanding continue to advance, deep generative models reinforced by learning algorithms are poised to become an indispensable tool in the accelerated discovery of transformative therapeutics.

The discovery and optimization of novel bioactive compounds represent a significant challenge in modern drug development, characterized by vast chemical spaces and costly experimental validation. Traditional methods often struggle to efficiently navigate this complexity. Reinforcement learning (RL), a subset of machine learning where intelligent agents learn optimal behaviors through environmental interaction, offers a powerful alternative [38]. This approach frames molecular design as a sequential decision-making process, mirroring the exploration-exploitation trade-offs observed in behavioral ecology, where organisms adapt their strategies to maximize rewards from their environment [2]. These parallels provide a unifying framework for understanding optimization across biological and computational domains. This application note details the integration of RL into molecular optimization workflows, providing structured protocols, data, and resources to facilitate its adoption in drug discovery research.

Key Reinforcement Learning Concepts in Molecular Design

In the RL framework for molecular design, an agent (a generative model) interacts with an environment (the chemical space and property predictors) [38]. The agent proposes molecular structures, transitioning between molecular states (e.g., incomplete molecular scaffolds) by taking actions (e.g., adding a molecular substructure) [39] [40]. Upon generating a complete molecule, the agent receives a reward based on how well the molecule satisfies target properties, such as bioactivity or synthetic accessibility [38] [41]. The objective is to learn a policy—a strategy for action selection—that maximizes the cumulative expected reward, thereby generating molecules with optimized properties [38].