Sexual Selection and Mating Strategies: Evolutionary Mechanisms, Research Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sexual selection and mating strategies for a scientific audience of researchers and drug development professionals.

Sexual Selection and Mating Strategies: Evolutionary Mechanisms, Research Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sexual selection and mating strategies for a scientific audience of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental definition and theoretical controversies of sexual selection as distinct from natural selection, detailing mechanisms from intrasexual competition to mate choice. The content examines cutting-edge methodological approaches for studying sexual selection, including behavioral assays, genetic analyses, and experimental evolution designs. It further investigates disruptions to mating strategies from environmental contaminants like endocrine-disrupting chemicals and explores therapeutic applications through genetic targets for non-hormonal male contraception. Finally, the article validates theories through comparative analyses across taxa and discusses implications for understanding mutation load, population fitness, and evolutionary innovation in biomedical contexts.

Defining Sexual Selection: From Darwinian Concepts to Modern Theoretical Frameworks

Sexual selection theory, as originally formulated by Charles Darwin, represents a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, proposing a mechanism for the evolution of traits that cannot be explained by natural selection alone. This foundational theory has sparked over a century of scientific debate and inquiry. Framed within the broader context of research on sexual selection and mating strategies, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of Darwin's original ideas, the immediate controversies they engendered, and the evolution of this scientific discourse, which remains highly relevant for modern researchers, including those in applied fields like drug development where understanding trait evolution is critical. The historical trajectory of this theory offers a compelling case study of how scientific knowledge is constructed and refined.

Darwin's Original Formulation of Sexual Selection

Charles Darwin first introduced the concept of sexual selection in On the Origin of Species (1859) and provided its comprehensive exposition in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). He proposed this secondary mechanism to account for the evolution of "secondary sexual characteristics"—conspicuous traits such as the longer manes in male lions, beards in male humans, and the contrasting bright and drab plumage in male and female birds—that were often maladaptive for survival but provided a reproductive advantage [1].

Darwin defined sexual selection as depending "not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females" [1]. He identified two primary mechanisms operating within this framework:

- Intrasexual Selection: Competition between members of the same sex (typically males) for access to mates, leading to the evolution of weapons like horns, antlers, tusks, and spurs.

- Intersexual Selection: The choice exerted by one sex (typically females) for members of the opposite sex, leading to the evolution of ornaments and displays. Darwin described this as a female 'aesthetic capacity' or 'taste for the beautiful' [2]. He argued that females, by choosing to mate with males that were the most attractive 'according to their standard of beauty', could influence the appearance and behaviour of future generations of males, analogous to the selective breeding practices of bird-fanciers [1].

A key and revolutionary aspect of Darwin's theory was its explicit aesthetic nature. He hypothesized that mate preferences could evolve for arbitrarily attractive traits that do not provide any additional utilitarian benefits to the female beyond being pleasing for their own sake [2]. The case of the male Argus Pheasant, Darwin argued, was "eminently interesting, because it affords good evidence that the most refined beauty may serve as a sexual charm, and for no other purpose" [2]. This non-utilitarian view positioned sexual selection as a distinct process from the utilitarian function of natural selection.

Table 1: Core Components of Darwin's Original Sexual Selection Theory

| Component | Definition | Example Given by Darwin |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Problem | To explain the evolution of seemingly maladaptive 'secondary sexual characteristics'. | The peacock's tail, which is cumbersome and may attract predators. |

| Mechanism 1: Male-Male Competition | A struggle between males for access to females, using "special weapons, confined to the male sex". | The horns of a stag, the spurs on a cock. |

| Mechanism 2: Female Mate Choice | Females exert choice based on a 'taste for the beautiful' or an 'aesthetic capacity'. | Female birds choosing males with the most attractive plumage or song. |

| Key Feature: Arbitrary Beauty | Traits can be advantageous simply because they are preferred, not because they signal underlying quality. | The distinct and seemingly arbitrary "standards of beauty" in different species. |

The Darwin-Wallace Controversy

The most significant initial controversy surrounding sexual selection emerged from Darwin's extensive correspondence and debate with Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of natural selection. This debate centered on the role and mechanism of female choice [1] [2].

Wallace was a staunch critic of Darwin's aesthetic interpretation. He maintained that natural selection was a more important driver of secondary sexual characteristics, particularly colouration [1]. For Wallace, traits like bright plumage were not merely beautiful; they served as honest signals of a male's underlying vigour, viability, or quality. Furthermore, he argued that the dull colouration of females was not due to a lack of aesthetic sense but had been acquired through natural selection for protection while nesting [1].

This fundamental disagreement represented a clash of two different evolutionary mechanisms:

- Darwin's Aesthetic Model: Traits evolve because they are aesthetically pleasing to the choosing sex, independent of any direct benefit or information content.

- Wallace's Utilitarian Model: Traits are honest indicators of quality, and female choice is ultimately adaptive because it secures better genes or resources for her offspring.

As science historian Evelleen Richards notes, this debate was stridently "anti-Darwinian and anti-aesthetic" on Wallace's part [2]. Although the two men reached a degree of compromise, with Darwin conceding the role of protective colouration, Darwin continued to emphasise the importance of sexual selection, particularly in humans [1]. This controversy laid the groundwork for a central tension that would persist in sexual selection research for more than a century.

Key Historical and Modern Controversies

Beyond the debate with Wallace, Darwin's theory of sexual selection has been the focal point of numerous other controversies, many of which have seen significant evolution in scientific understanding.

Female Agency and the Legacy of Gender Bias

A major area of contention has been the role and agency of females. Darwin's descriptions of females were often gender-biased, reflecting his Victorian social context; he frequently portrayed females as passive and coy [3]. This bias had a long-lasting impact on the field. An examination of the history of sexual selection research shows a prevalent pattern of male precedence—where research starts with male-centered investigations and only later includes female-centered equivalents [3].

Table 2: Examples of Male Precedence in Sexual Selection Research

| Research Area | Male-Centered Focus (Earlier) | Female-Centered Equivalent (Later) |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Copulatory Selection | Sperm competition (Parker, 1970) [3]. | Cryptic female choice (Thornhill, 1983) [3]. |

| Genital Evolution | Focus on male copulatory organs (e.g., Eberhard, 1985) [3]. | Delayed study of female genitalia and their co-evolutionary role [3]. |

| Multiple Mating | Interpreted as male harassment or forced copulation [3]. | Recognized as an active female strategy for genetic benefits [3]. |

| Infanticide | Sexually selected strategy in males (Hrdy, 1974) [3]. | Considered as a sexually selected strategy in females only much later [3]. |

This male bias is not merely historical. A analysis of publication volumes shows that studies on sexual selection in males far outnumber those on females, a pattern that persists to the present day [3]. This bias has been driven by the conspicuous nature of male traits, practical obstacles, and a continued gender bias in how questions are framed [3]. The very definition of sexual selection has contributed to this imbalance. As noted in a 2022 Nature Communications perspective, this history provides an illustrative example for learning to recognize and counteract biases in scientific knowledge production [3].

The "Really Dangerous" Idea of Aesthetic Evolution

The core of Darwin's aesthetic view—that traits could be arbitrary and evolve simply because they are preferred—was largely rejected for decades following the Darwin-Wallace debate. This concept, dubbed Darwin's "really dangerous idea," was overshadowed by the Neo-Wallacean honest advertisement paradigm, which came to dominate 20th-century sexual selection research [2].

The modern revival of this debate is anchored in the Lande-Kirkpatrick (LK) null model, a mathematical formulation of Fisher's runaway process, which demonstrates how traits and preferences can co-evolve in a self-reinforcing cycle without requiring the trait to signal any inherent benefit [2]. Proponents for a more Darwinian aesthetic theory argue that the LK model should be the null model in sexual selection research, with honest signaling treated as a competing hypothesis to be tested, rather than the default assumption [2]. This remains an active and contentious area of theoretical debate.

Sexual Selection and Population Fitness

A long-standing theoretical controversy concerns the net effect of sexual selection on population fitness. Does it strengthen or weaken a population's ability to survive and thrive? Theories have predicted both positive effects (e.g., by purging deleterious mutations) and negative effects (e.g., through sexual conflict and the costs of traits) [4].

A 2019 meta-analysis in Nature Communications synthesized data from 65 experimental evolution studies to resolve this question. The key findings are summarized in the table below, providing quantitative evidence for the population-level consequences of sexual selection.

Table 3: Meta-Analytic Evidence on Sexual Selection and Population Fitness

| Fitness Component Category | Effect of Sexual Selection (Hedges' g) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Fitness Traits (e.g., lifespan, mating success) | +0.24 (95% CI: 0.13 - 0.36) [4] | Significant positive effect. |

| Ambiguous Relationship to Fitness (e.g., body size, mating duration) | +0.21 (95% CI: 0.058 - 0.093) [4] | Significant positive effect. |

| Direct Fitness Traits (e.g., female reproductive success, offspring viability) | +0.13 (95% CI: 0.019 - 0.24) [4] | Significant positive effect, but smaller. |

| Immunity | -0.42 (95% CI: -0.64 to -0.20) [4] | Significant negative effect. |

| Overall Mean Effect | +0.24 (95% CI: 0.055 - 0.43) [4] | Net positive effect across studies. |

The meta-analysis further revealed that the benefits of sexual selection are context-dependent. The positive effect was significantly stronger for female fitness and for populations evolving under stressful conditions [4]. This suggests that sexual selection can play a crucial role in adaptation, particularly in changing environments, by accelerating the purging of deleterious alleles and promoting beneficial genotypes.

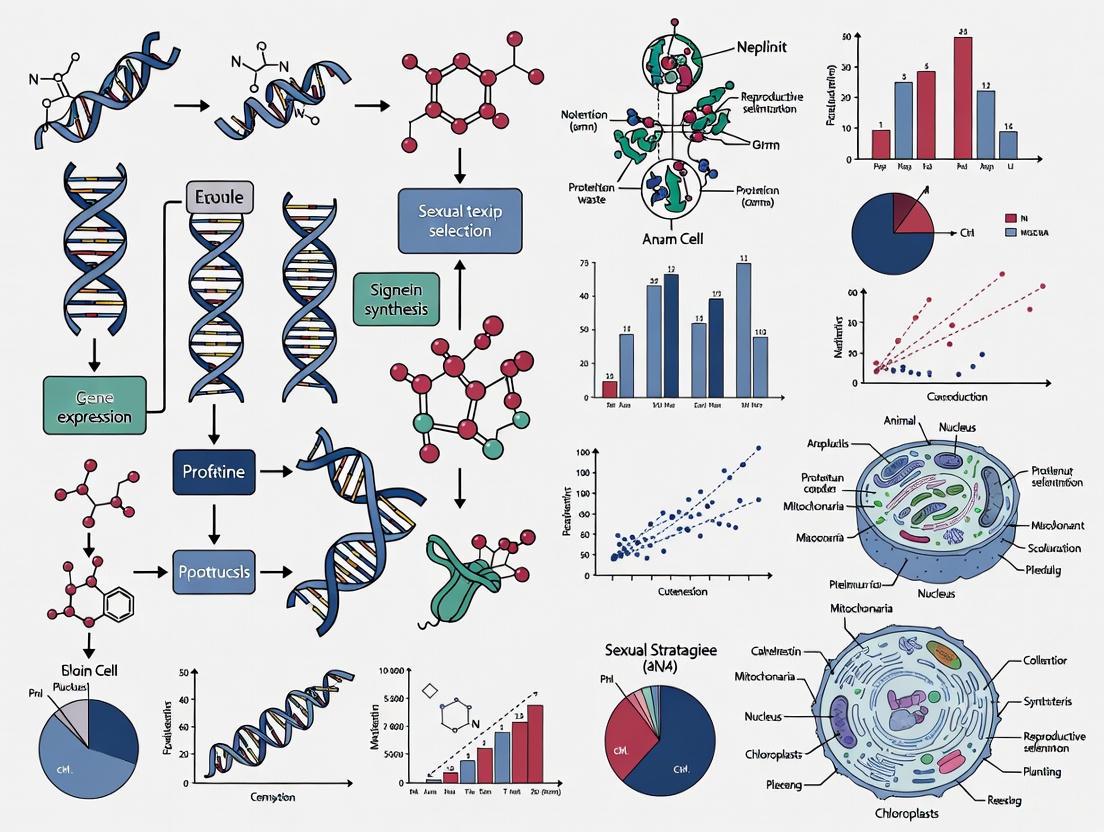

Conceptual Frameworks and Research Workflows

The following diagrams map the logical structure of Darwin's theory and the historical pattern of research bias, providing a visual synthesis of the concepts discussed.

Darwin's Framework of Sexual Selection

Darwin's Sexual Selection Theory

Historical Bias in Research Focus

Male Precedence in Sexual Selection Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Modern research into sexual selection and its applications relies on a suite of methodological approaches and conceptual "reagents". The following table details several key solutions essential for investigating the foundations and controversies discussed in this paper.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Research Reagent / Method | Function in Sexual Selection Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Evolution | To empirically test the causal effect of sexual selection on population fitness and other traits by manipulating mating regimes. | Comparing populations with enforced monogamy (no sexual selection) vs. polygamy (strong sexual selection) over multiple generations [4]. |

| Molecular Genetic Tools (DNA sequencing) | To establish paternity, measure genetic variation, and identify genes underlying sexually selected traits and preferences. | Revealing widespread extra-pair paternity in socially monogamous birds, forcing a re-evaluation of female mating strategies [3]. |

| Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis | To reconstruct the evolutionary history of traits and test hypotheses about correlated evolution across species. | Testing whether the evolution of male ornaments is correlated with the evolution of female preferences across a clade of species. |

| The Lande-Kirkpatrick (LK) Model | A mathematical null model for testing the feasibility of trait-preference coevolution without direct fitness benefits (Fisherian process). | Used to determine if a trait could evolve via arbitrary aesthetic choice before invoking honest signaling hypotheses [2]. |

| Meta-Analysis | To quantitatively synthesize results from multiple independent studies and identify general patterns. | Establishing that sexual selection on males generally improves female and population fitness, especially under stress [4]. |

| Sinopodophylline B | Sinopodophylline B, MF:C21H20O7, MW:384.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Poricoic Acid H | Poricoic Acid H, MF:C31H48O5, MW:500.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The theory of evolution by natural selection represents a foundational pillar of modern biology, but within this broad framework, sexual selection operates as a distinct and powerful evolutionary mechanism. While both processes drive evolutionary change through differential survival and reproduction, they arise from different selective pressures and often produce markedly different phenotypic outcomes. Natural selection encompasses any process where heritable traits influence an organism's survival and reproductive success, primarily through adaptation to the environment. In contrast, sexual selection specifically arises from differential access to mating opportunities and gamete fertilization, driven by competition for mates and mate choice [5]. This distinction is not merely academic; it has profound implications for understanding biodiversity, speciation events, and the evolution of traits that may appear maladaptive from a purely survival-oriented perspective but confer significant reproductive advantages.

The conceptual separation of sexual selection from natural selection dates back to Charles Darwin's seminal work, where he recognized that many conspicuous animal traits could not be adequately explained by survival advantages alone. Darwin observed that traits such as the peacock's elaborate tail seemed to contradict the principle of natural selection by imposing obvious survival costs, yet persisted because they provided mating advantages. This insight established sexual selection as a distinct evolutionary process that could, in certain circumstances, operate in direct opposition to natural selection [5]. Contemporary research continues to refine this distinction, investigating how these dual selective forces interact across different species, environments, and social systems.

Defining Principles and Key Differences

Natural Selection: Survival and Environmental Adaptation

Natural selection is the process whereby organisms better adapted to their environment tend to survive and produce more offspring. It encompasses all selective pressures related to environmental adaptation, including predator avoidance, resource acquisition, thermoregulation, disease resistance, and physiological efficiency. The metric of success in natural selection is fundamentally survival viability – the ability to navigate environmental challenges from conception through reproductive age and beyond. Traits favored by natural selection typically enhance an organism's probability of survival or its efficient utilization of environmental resources, leading to characteristics such as protective coloration, efficient metabolic pathways, defensive structures, and physiological resilience to environmental stressors [5].

The operation of natural selection produces phenotypes optimized for environmental interaction, often resulting in traits that provide clear survival benefits. Camouflage patterns that reduce predation risk, digestive specializations that maximize nutrient extraction from available food sources, thermoregulatory adaptations that maintain optimal body temperature across seasonal variations – all exemplify outcomes predominantly driven by natural selection. These adaptations typically represent compromises between competing physiological demands and environmental constraints, yielding solutions that maximize survival probability within a given ecological context.

Sexual Selection: Competition for Mating Opportunities

Sexual selection operates specifically on variation in mating success and encompasses two primary mechanisms: intrasexual competition (same-sex competition for access to mates) and intersexual selection (mate choice, where individuals of one sex choose mates based on particular traits). Unlike natural selection, which focuses on survival adaptation, sexual selection centers on reproductive success irrespective of survival value. Traits favored by sexual selection may include elaborate ornaments, complex courtship behaviors, weaponry for intrasexual combat, and physiological adaptations for gamete competition [5] [6].

The quintessential example of sexual selection is the peacock's tail, which imposes clear survival costs through increased predation risk and metabolic investment yet persists because it significantly enhances mating success through female preference [5]. Similarly, the large mandibles of male broad-horned flour beetles win male-male contests and increase matings despite necessitating a masculinized body with a smaller abdomen that would limit egg production in females [6]. These traits demonstrate that sexual selection can promote characteristics that directly oppose survival advantages, maintaining them in populations through their reproductive benefits.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Natural and Sexual Selection

| Aspect | Natural Selection | Sexual Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Selective Pressure | Environmental adaptation, survival | Mating success, fertilization |

| Key Mechanisms | Predator-prey dynamics, resource competition, environmental stress | Mate choice, intrasexual competition, sperm competition |

| Trait Outcomes | Camouflage, physiological efficiency, defensive structures | Ornaments, weapons, courtship displays, genital complexity |

| Metric of Success | Survival to reproductive age, longevity | Number of mates, fertilization success, number of offspring |

| Potential Conflict | Maximizes survival probability | May reduce survival while enhancing mating success |

Quantitative Frameworks and Measurement

Statistical Detection and Measurement

Quantifying the strength and operation of sexual selection requires specialized statistical approaches that distinguish its effects from those of natural selection. Modern evolutionary biology employs information theory and variance-based metrics to partition selection into its components. The Jeffreys divergence measure (JPTI) quantifies the information gained when mating deviates from random expectation, with this total divergence decomposable additively into components measuring sexual selection (JS1 and JS2 for females and males respectively) and assortative mating (JPSI) [7].

For continuous traits following normal distributions, sexual selection strength can be measured using formulas that compare the distribution of traits in mated individuals versus the general population. For a female trait X with mean μ₠and variance σ₲ among mated females and mean μₓ and variance σₓ² in the female population, the strength of sexual selection is given by:

$$J{S1}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\varPhi1{^2}+1}{\varPhi1}+\frac{\varPhi{1}+1}{\varPhi1}\frac{(\mu1-\mux)^2}{\sigmax^{2}}-2\right)$$

where Φ₠= σ₲/σₓ² [7]. A similar calculation (JS2) measures sexual selection on male traits. These statistical approaches allow researchers to detect and quantify sexual selection independent of natural selection's effects on survival.

Empirical Measurements in Human and Model Systems

Research on preindustrial Finnish populations (1760-1849) provides compelling empirical data on the relative strengths of natural and sexual selection in humans. This study quantified the opportunity for selection (I), calculated as the variance in relative lifetime reproductive success. The total opportunity for selection (I = 2.27) revealed that natural selection (through differential survival) and sexual selection (through variance in mating success) created significant potential for evolutionary change, with I being 24.2% higher in males than females, indicating stronger sexual selection on males [8].

The Bateman gradient, which measures the relationship between mating success and reproductive success, provides another key metric for quantifying sexual selection. In the Finnish population, variance in mating success explained most of the higher variance in reproductive success in males compared to females, confirming stronger sexual selection on males, though mating success also influenced female reproductive success, allowing for sexual selection in both sexes [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of Selection in a Preindustrial Finnish Population [8]

| Metric | Males | Females | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunity for total selection (I) | Higher (24.2% > females) | Lower | Maximum potential evolutionary change per generation |

| Variance in reproductive success | Higher | Lower | Reflects combined natural/sexual selection |

| Variance in mating success | Higher | Lower | Direct measure of sexual selection component |

| Bateman gradient | Steeper | Shallower | Stronger relationship between mating success and reproductive output |

| Selection differential | Up to 1.51 SD per generation | Up to 1.51 SD per generation | Maximum possible trait change per generation |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Direct Experimental Manipulation

Controlled experiments demonstrating the opposition between natural and sexual selection provide the most compelling evidence for their distinctiveness. A landmark study on broad-horned flour beetles (Gnatocerus cornutus) directly manipulated these selective forces. Male beetles develop exaggerated mandibles for fighting competitors, a trait favored by sexual selection through male-male competition. However, these large mandibles require a masculinized body with a smaller abdomen, which is detrimental for females as it limits egg capacity – a case of intralocus sexual conflict where genes beneficial for one sex are suboptimal for the other [6].

When researchers introduced predation pressure from assassin bugs, predators selectively targeted males with the largest mandibles, demonstrating natural selection opposing sexually selected traits. After eight generations of this experimental regime, females produced approximately 20% more offspring across their lifespans because the removal of extreme males by predators reduced the sexual conflict, allowing female body plans to move closer to their optimal form [6]. This experiment elegantly demonstrates how natural selection can reverse evolutionary changes driven by sexual selection and resolve sexual conflicts over shared traits.

Diagram 1: Sexual vs Natural Selection Conflict in Flour Beetles. This diagram illustrates the opposing selective pressures on male morphological traits in broad-horned flour beetles, demonstrating intralocus sexual conflict.

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Toolkit

Contemporary research on sexual selection employs sophisticated methodological tools across laboratory and field settings. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in studying selection dynamics:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| QInfoMating Software | Statistical analysis of mating data; detects sexual selection and assortative mating using information theory | Analysis of both discrete and continuous trait data in mating studies [7] |

| Jeffreys Divergence (JPTI) | Quantifies deviation from random mating; decomposes into sexual selection (JS1, JS2) and assortative mating (JPSI) components | Quantitative measurement of selection strength from mating table data [7] |

| Population Pedigree Databases | Complete life history data including survival, mating, and reproductive success for defined populations | Studies of selection in historical human populations (e.g., Finnish church records) [8] |

| Model Organism Systems | Controlled experimentation on selection pressures (e.g., flour beetles, guppies) | Experimental manipulation of selective pressures [5] [6] |

| Bateman Gradient Analysis | Regression of reproductive success on mating success; measures strength of sexual selection | Comparing sexual selection intensity between sexes and populations [8] |

| Tessaric Acid | Tessaric Acid, MF:C15H20O3, MW:248.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Eupalinolide I | Eupalinolide I, MF:C24H30O9, MW:462.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Studies and Empirical Evidence

Trinidadian Guppies: Environmental Mediation of Selection

The classic study of Trinidadian guppies (Poecilia reticulata) provides a compelling natural experiment demonstrating how ecological factors mediate the balance between natural and sexual selection. Male guppies exhibit striking color polymorphisms, with females preferring to mate with males displaying bright red spots – a clear case of intersexual selection. However, the distribution of these color patterns across different stream habitats reveals how natural selection constrains sexual selection [5].

In streams with few predators, male guppies predominantly display the bright red coloration preferred by females. In contrast, in streams containing the crayfish (Macrobrachium crenulatum), a visual predator with good color vision, male guppies are predominantly drab green. The crayfish selectively prey upon conspicuous red males, creating a natural selection pressure that opposes the female preference. This environmental gradient demonstrates the dynamic balance between selective forces, with sexual selection predominant in low-predation environments and natural selection constraining sexual ornamentation where predators are present [5].

Speciation and Reproductive Isolation

Sexual selection can drive speciation through the evolution of mating traits and preferences that create reproductive barriers. Research on Capsella plants reveals how shifts in mating systems and sexual selection intensity promote speciation. The self-fertilizing species Capsella rubella recently evolved from the outcrossing C. grandiflora, resulting in significant reproductive isolation between the lineages [9].

The difference in sexual selection intensity between these lineages creates asymmetric prezygotic barriers: traits enhancing male competitiveness in outcrossers decrease their pollination success by selfers, while efficient self-fertilization mechanisms in selfers limit hybridization. This demonstrates how changes in sexual selection and mating systems can drive speciation through multiple complementary mechanisms, including pollinator-mediated isolation and postzygotic incompatibilities [9].

Diagram 2: Sexual Selection's Role in Speciation. This diagram illustrates how shifts in mating systems and sexual selection intensity create reproductive isolation between plant lineages, as observed in Capsella species.

Implications for Applied Research

Evolutionary Medicine and Drug Discovery

Understanding the distinction between natural and sexual selection provides valuable insights for applied fields including medicine and pharmaceutical development. Evolutionary perspectives help explain puzzling medical phenomena, such as why harmful genetic disorders persist in populations and why antibiotic resistance develops so rapidly. The principles of sexual selection illuminate why certain genetically influenced conditions that reduce survival nevertheless persist because they may have historically enhanced mating success [10] [11].

The drug discovery process itself mirrors evolutionary selection pressures, with high attrition rates eliminating most candidate molecules while a few successful variants survive to become medicines. This analogy helps identify factors favoring successful drug development, including the importance of variation (chemical diversity), selection criteria (efficacy and safety), and environmental context (regulatory and market pressures) [10]. Recognizing these parallels allows researchers to structure discovery pipelines to maximize innovation while managing attrition.

Conservation Biology and Population Management

The distinction between natural and sexual selection has practical implications for conservation biology and wildlife management. Conservation strategies focused solely on population viability may inadvertently select against sexually selected traits critical for reproductive success. For example, captive breeding programs that randomize mating opportunities may diminish sexual selected traits that would be essential for success in wild populations, potentially reducing reintroduction success.

Understanding how environmental changes differentially affect natural versus sexual selection components helps predict evolutionary responses to human disturbances such as habitat fragmentation, pollution, and climate change. For instance, environmental contaminants that impair the development of sexual ornaments or courtship behaviors may disrupt mating systems without directly affecting survival, leading to population declines not predicted by traditional viability analyses.

Sexual selection, a concept formally introduced by Charles Darwin in 1871, is a fundamental evolutionary force driven by differential reproductive success [12] [13] [14]. This framework explains the evolution of traits that enhance mating success, even at the cost of survival [15]. Darwin identified two primary mechanisms: intrasexual competition, where members of one sex compete for access to mates, and intersexual selection (mate choice), where one sex chooses specific partners based on preferred traits [13] [14]. Modern evolutionary biology has expanded this framework to include post-copulatory processes, most notably sperm competition, which occurs when gametes from multiple males compete to fertilize a female's eggs [16]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these three core mechanisms—intrasexual competition, mate choice, and sperm competition—synthesizing current research, experimental methodologies, and quantitative findings for a scientific audience.

Core Theoretical Frameworks

Intrasexual Competition

Intrasexual competition involves contests between individuals of the same sex (typically males) for mating access to the opposite sex [14] [15]. This competition drives the evolution of weaponry (e.g., antlers, horns), large body size, and aggressive behaviors. The outcome of these contests directly influences reproductive success, with winners gaining more mating opportunities [15]. A key principle underlying this competition is Bateman's principle, which states that the sex investing less in offspring (usually males) becomes a limiting resource for which the other sex competes [14]. Recent experimental evolution studies manipulating the strength of intrasexual competition, for instance by skewing sex ratios, have demonstrated its power to drive rapid sex-specific evolution in life-history traits such as body size and fecundity [17].

Mate Choice

Mate choice, or intersexual selection, describes the selective response by animals to particular stimuli from potential mates [12]. The choosy sex (often females) evaluates traits indicative of a potential mate's quality, such as resources, phenotypes, or genetic compatibility [12] [18]. Several hypotheses explain the evolution of mate preferences:

- Direct Phenotypic Benefits: The choosy sex gains direct material advantages, such as superior parental care, higher quality territory, or protection from predators [12]. For example, female Northern Cardinals prefer males with brighter plumage, who subsequently provide more frequent feedings to their young [12].

- Sensory Bias: A preference for a trait evolves in a non-mating context (e.g., foraging) and is later exploited by the competitive sex to attract mates [12]. Guppies, for instance, are naturally attracted to orange objects (possibly due to an association with fruit), and males have evolved large orange spots to capitalize on this pre-existing bias [12].

- Fisherian Runaway: A feedback loop occurs where a heritable preference for an extreme ornament and the ornament itself become genetically correlated. This leads to the runaway evolution of ever-more exaggerated traits, like the peacock's tail, until checked by natural selection [12] [14].

- Indicator Traits and Honest Signaling: Ornaments serve as honest signals of genetic quality or condition because they are too costly to produce or maintain for low-quality individuals [14] [19]. The handicap principle posits that surviving with a seemingly maladaptive trait reliably signals a male's overall fitness [14].

Sperm Competition

Sperm competition is a post-copulatory form of male-male competition that occurs when females mate with multiple males, and their sperm compete for fertilization [16]. This process is a powerful selective force shaping male reproductive anatomy, physiology, and behavior [16] [20]. Key concepts include:

- The "Fair Raffle" Principle: A male's probability of siring offspring is proportional to the number of sperm he inseminates relative to other males [20]. This selects for increased sperm production, which is often correlated with larger testicular size [16].

- Sperm Quality: Beyond quantity, competition favors sperm with greater velocity, longevity, and viability [16] [20].

- Strategic Allocation: Males may adjust ejaculate expenditure based on the perceived risk of sperm competition [16].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Sexual Selection Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Definition | Primary Evolutionary Outcome | Classic Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrasexual Competition | Competition within one sex for access to mates [14]. | Evolution of weapons, large size, and aggressive behaviors [15]. | Male deer fighting with antlers [15]. |

| Mate Choice | Selective choice of mates based on specific traits [12]. | Evolution of ornaments, displays, and sensory adaptations [12]. | Peahen preference for peacocks with elaborate trains [12]. |

| Sperm Competition | Competition between sperm from different males to fertilize eggs [16]. | Evolution of sperm number, quality, and strategic ejaculation [16] [20]. | Higher sperm production in polyandrous ant species [20]. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Sperm Competition in Cataglyphis Ants

A 2023 study on Cataglyphis desert ants provides robust, phylogenetically-controlled evidence of how sperm competition molds ejaculate traits [20]. The research measured sperm production (number in accessory testes), sperm viability (proportion of live sperm), and sperm DNA fragmentation across nine species with varying levels of polyandry (a proxy for sperm competition intensity) [20].

Table 2: Correlations between Sperm Competition Intensity and Sperm Traits in Cataglyphis Ants [20]

| Sperm Trait | Correlation with Sperm Competition Intensity | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Production | Positive | p < 0.01 | Males in high-competition species produce more sperm, increasing their representation in the "fair raffle" [20]. |

| Sperm Viability | Positive | p < 0.05 | Higher proportions of live sperm enhance competitive fertilization success [20]. |

| Sperm DNA Fragmentation | No significant relationship | p > 0.05 | Suggests no trade-off between quantity and DNA integrity; quality is maintained despite increased production [20]. |

Intrasexual Competition in Caenorhabditis remanei

An experimental evolution study on the nematode C. remanei (2020) tested the effects of intrasexual competition by evolving populations under female-biased (FB, 10:1) and male-biased (MB, 1:10) sex ratios for 30 generations [17]. This manipulation directly altered the strength of sex-specific selection, with the common sex in each treatment experiencing intensified intrasexual competition [17].

Table 3: Evolutionary Responses to Skewed Sex Ratios in C. remanei [17]

| Trait | Treatment | Response in Females | Response in Males | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Size | Female-Biased (FB) | Increased | Little change | Stronger net selection on females under increased female-female competition [17]. |

| Body Size | Male-Biased (MB) | Little change | Increased | Stronger selection on males under increased male-male competition [17]. |

| Peak Fitness (λpeak) | Female-Biased (FB) | Increased | Decreased | Sex-specific evolutionary responses; females evolved higher peak fitness under FB conditions [17]. |

| Peak Fitness (λpeak) | Male-Biased (MB) | Decreased | Increased | Opposite response to FB, confirming sex-specific trade-offs [17]. |

Meta-Analytic Support for Mate Choice

A large-scale augmented meta-meta-analysis (2025) unified decades of research on conspicuous traits, analyzing 7428 effect sizes from 375 animal species [19]. The analysis confirmed that the conspicuousness of putative sexual signals is positively related to the bearer's mate attractiveness, fitness benefits, and individual condition, supporting key predictions of sexual selection theory [19]. These patterns were largely consistent across taxa and sexes, demonstrating the generalizability of the theory.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantifying Sperm Traits via Flow Cytometry

This protocol, adapted from a 2023 study on ants, details how to measure sperm production and quality [20].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Species: Cataglyphis spp. (applicable to other insects).

- Subjects: Sexually mature males (8-10 days post-emergence for ants).

- Dissection: Decapitate males and dissect both accessory testes in 1 ml of semen diluent (188.3 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM glucose, 574.1 nM arginine, 684.0 nM lysine, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.7). Remove membranes and mix to create a sperm stock solution [20].

2. Sperm Viability Staining:

- Aliquot 150 µl of sperm stock into a vial and add 850 µl of semen diluent. Prepare two technical replicates per male.

- Add 5 µl of SYBR 14 (100 nM), a green-fluorescent nucleic acid stain that labels live sperm. Incubate for 10 minutes in the dark.

- Add 5 µl of propidium iodide (PI, 12 mM), a red-fluorescent stain that labels membrane-compromised dead sperm. Incubate for 10 minutes in the dark [20].

3. Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Use a flow cytometer (e.g., CyFlow Space) with a 488 nm blue laser.

- Measure SYBR-14 fluorescence with a 536/40 nm bandpass filter and PI fluorescence with a >630 nm long-pass filter.

- Set a flow rate of 1 µl/s, allowing the stream to stabilize for 25s before counting.

- Use forward and side scatter to identify the sperm cell population.

- Gating and Quantification: Use software (e.g., FlowJo) to gate populations. Total sperm count gives sperm production. The ratio of SYBR-14+/PI- cells to total sperm gives sperm viability [20].

Protocol: Experimental Evolution of Intrasexual Competition

This protocol is based on a 2020 study using nematodes [17].

1. Base Population and Maintenance:

- Use a well-defined ancestral population (e.g., C. remanei strain SP8). Cryopreserve a large number of individuals to serve as a baseline for future comparisons.

- Maintain populations on standard nematode growth medium seeded with a food source (e.g., E. coli OP50) [17].

2. Selection Regime:

- Establish replicate populations for each treatment:

- Female-Biased (FB): 10 females : 1 male

- Male-Biased (MB): 1 female : 10 males

- Control (if used): 1 female : 1 male

- At each generation, randomly select the specified number of adults to found the next generation, ensuring the designated sex ratio is maintained. This forces the overrepresented sex to compete for access to the limited opposite sex.

- Run selection for a sufficient number of generations (e.g., 30+) to allow for evolutionary change [17].

3. Phenotypic Assay:

- After the selection period, revive the ancestral population and compare it simultaneously with the evolved lines to control for environmental effects.

- Measure key life-history traits: Body size (via microscopy), fecundity (egg count), and stress resistance (e.g., heat tolerance via time-to-death assay at a high temperature).

- Use appropriate statistical models (e.g., ANOVA with treatment and sex as factors) to test for evolutionary responses [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Semen Diluent | An isotonic solution to maintain sperm viability and motility during in vitro handling [20]. | Dissection and preparation of sperm stock solutions for flow cytometry [20]. |

| SYBR 14 & Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent viability stains for sperm. SYBR-14 labels live cells (green), PI labels dead cells (red) [20]. | Differentiating live from dead spermatozoa in a population for quality assessment via flow cytometry [20]. |

| Flow Cytometer | An instrument for rapid, quantitative multiparameter analysis of single cells in a fluid stream [20]. | Simultaneous quantification of total sperm production and percent viability in a sample [20]. |

| QInfoMating Software | A computational tool for analyzing mating data, performing model selection, and estimating sexual selection and assortative mating parameters [7]. | Statistical testing and model-fitting for discrete or continuous mating data to detect patterns of mate choice and competition [7]. |

| Carpinontriol B | Carpinontriol B, MF:C19H20O6, MW:344.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sarasinoside B1 | Sarasinoside B1, MF:C61H98N2O25, MW:1259.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Conceptual Diagrams and Workflows

The Interconnected Mechanisms of Sexual Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and feedback loops between the three core mechanisms.

Experimental Workflow for Sperm Trait Analysis

This workflow outlines the key steps in the protocol for analyzing sperm competition traits, as described in Section 4.1.

The lek paradox presents a fundamental challenge in evolutionary biology: how is substantial genetic variation maintained in male sexually selected traits despite persistent female choice that should theoretically erode this variation? This whitepaper examines the core theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence addressing this paradox, with particular focus on implications for understanding evolutionary processes and their unexpected connections to medical genetics. We synthesize current research demonstrating how mechanisms like condition-dependent expression, mutation-selection balance, and indirect genetic effects resolve this paradox, providing crucial insights into the maintenance of genetic diversity under strong selection pressures.

The lek paradox originates from observations of lek mating systems, where males aggregate and compete for female attention, and females select mates without receiving direct benefits like resources or parental care [21]. This system creates a conceptual challenge: if females consistently choose males based on specific secondary-sexual characteristics, the persistent directional selection should deplete additive genetic variance for these traits over generations [22] [21]. Without genetic variation, the indirect genetic benefits (so-called "good genes") that females presumably gain through mate choice would disappear, making the persistence of costly female preferences evolutionarily paradoxical [22].

This paradox raises two fundamental questions for sexual selection theory: (1) Do females genuinely obtain genetic benefits for offspring by selecting males with elaborate secondary-sexual characteristics? (2) If so, what mechanisms maintain the genetic variation in these male traits despite strong directional selection? [22] Resolving these questions is essential for understanding the evolutionary consequences of mate choice across diverse taxa.

Theoretical Frameworks for Resolution

Several complementary hypotheses have been proposed to explain the maintenance of genetic variation in the face of persistent sexual selection. The table below summarizes the key theoretical frameworks and their core mechanisms.

Table 1: Theoretical Frameworks for Resolving the Lek Paradox

| Theory/Framework | Core Mechanism | Key Predictions | Primary Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genic Capture Hypothesis [22] [23] | Sexually selected traits capture genetic variation in condition, which depends on many loci throughout the genome | Condition-dependent traits show high genetic variance; sexual selection erodes genome-wide variation | Molecular evolution experiments in Drosophila [23]; meta-analyses of condition dependence [19] |

| Indirect Genetic Effects [22] | Maternal genotypes influence offspring condition and trait expression through environmental effects | Female choice targets genes for effective maternal characteristics; genetic variation maintained across generations | Mathematical models; cross-generational studies of maternal effects [22] |

| Parasite Resistance Hypothesis [21] | Host-parasite coevolutionary cycles continuously generate new genetic variation | Male ornaments signal parasite resistance; genetic variation maintained through Red Queen dynamics | Correlation between ornamentation and parasite load across bird species [21] |

| Handicap Principle [21] | Costly signals honestly indicate genetic quality because only high-quality males can bear the costs | Ornaments reduce survival; signal expression correlates with overall viability | Studies of predator attraction and energy costs of displays [21] |

The Genic Capture Hypothesis

The genic capture hypothesis, proposed by Rowe and Houle, suggests that sexually selected traits capture genetic variation from across the genome because these traits are condition-dependent [22] [23]. Condition represents the pool of resources available for allocation to fitness-related traits and is influenced by many loci throughout the genome [23]. This creates a large mutation target for maintaining genetic variation through mutation-selection balance [23].

According to this model, female preference for males with elaborate traits essentially represents selection for males with a lower mutational load [23]. A key prediction is that strong sexual selection should deplete genetic variation, while relaxation of selection should allow variation to accumulate. Molecular evidence from experimental evolution studies in Drosophila melanogaster supports this prediction: lines selected for high male mating success showed significantly reduced genetic variation compared to lines selected for mating failure [23].

Indirect Genetic Effects

Indirect genetic effects (IGEs) provide another resolution to the lek paradox by emphasizing how genes expressed in one individual can influence trait expression in others [22]. Specifically, maternal phenotypes—such as habitat selection behaviors and offspring provisioning—often influence the condition and expression of secondary-sexual traits in sons, and these maternal influences frequently have a genetic basis [22].

This framework suggests that females choosing mates with elaborate traits may receive 'good genes' for daughters in the form of effective maternal characteristics [22]. By this mechanism, genetic variation is maintained because selection acts on the interplay between direct and indirect genetic effects across generations, creating a more complex evolutionary dynamic than simple directional selection [22].

Quantitative Evidence and Meta-Analytic Support

Recent comprehensive syntheses have provided robust quantitative support for key predictions of sexual selection theory. An augmented meta-analysis of 41 meta-analyses, encompassing 375 animal species and 7428 individual effect sizes, demonstrates consistent relationships between trait conspicuousness and fitness benefits [19].

Table 2: Summary of Meta-Analytic Relationships Between Conspicuousness and Fitness Components

| Relationship Assessed | Effect Direction | Strength of Support | Taxonomic Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conspicuousness Mate attractiveness | Positive | Strong | Consistent across taxa and sexes |

| Conspicuousness Fitness benefits | Positive | Strong | Consistent across taxa and sexes |

| Conspicuousness Individual condition | Positive | Strong | Consistent across taxa and sexes |

| Conspicuousness Other traits (e.g., body size) | Positive | Moderate | Variable across trait types |

| Pre-copulatory sexual selection Conspicuousness-benefits relationship | Positive | Strong | Consistent across studies |

This meta-analysis revealed that the strength of pre-copulatory sexual selection on conspicuousness is positively associated with both the relationship between conspicuousness and fitness benefits and the relationship between conspicuousness and individual condition [19]. This pattern underscores the fundamental connection between sexual signal honesty and the intensity of mate choice.

Experimental Evidence and Molecular Validation

Experimental Evolution Protocol

Recent research has applied experimental evolution approaches combined with genome sequencing to directly test predictions of the genic capture hypothesis [23]. The following methodology provides a template for such investigations:

Selection Protocol:

- Establish replicate populations for bidirectional selection on male mating success

- For success-selected lines: Propagate using males that successfully secure matings in competitive trials

- For failure-selected lines: Propagate using males that fail to secure matings

- Maintain control lines with random selection of breeders

- Continue selection for multiple generations (typically 10-20) to allow evolutionary divergence

Genomic Analysis:

- Sequence genomes from pooled individuals of each selection line after generations of divergence

- Identify genetic polymorphisms and calculate allele frequencies

- Compute expected heterozygosity (He) as 2pq for each locus

- Apply statistical approaches (e.g., DiffStat, generalized linear models) to identify significantly diverged variants between selection regimes

- Perform Gene Ontology analysis to identify functional enrichment in diverged regions

Key Measurements:

- Genome-wide heterozygosity estimates

- Allele frequency spectra

- Distribution of significantly diverged variants across chromosomes

- Functional annotation of candidate regions

This approach directly tests whether sexual selection reduces genetic variation, as predicted by the genic capture hypothesis [23].

Key Findings from Molecular Studies

Application of the above protocol in Drosophila melanogaster revealed that success-selected lines had significantly lower genetic variation than failure-selected lines, with this pattern distributed across the genome [23]. Specifically, only 4.4% of significantly diverged variants showed higher heterozygosity in success-selected lines, strongly supporting the action of purifying sexual selection [23].

This molecular evidence demonstrates that sexual selection erodes genetic variation and that mutation-selection balance across the genome contributes to its maintenance, consistent with the genic capture resolution to the lek paradox [23].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Lek Paradox Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Evolution Lines | Bidirectional selection on mating success to test evolutionary responses | Requires large population sizes to minimize drift; multiple replicates essential |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing | Identify genetic variants and quantify genome-wide variation | Pool-seq cost-effective for population analyses; individual sequencing provides haplotype information |

| Condition Manipulations | Test condition dependence of sexually selected traits | Nutritional stress, parasite load, or physiological challenges |

| Mate Choice Trials | Quantify female preferences and mating success | Controlled environments to minimize confounding variables; standardized protocols |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | Identify gene expression patterns associated with trait expression | Tissue-specific sampling; integration with genomic data |

| Pedigree Analysis | Track genetic contributions across generations | Long-term monitoring of wild or captive populations |

| Phylogenetic Comparative Methods | Test evolutionary patterns across species | Control for phylogenetic non-independence; large species datasets |

| Isoedultin | Isoedultin, MF:C21H22O7, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dregeoside Da1 | Dregeoside Da1, MF:C42H70O15, MW:815.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Medical Genetics and Pharmacogenomics

Interestingly, research on the lek paradox intersects with medical genetics and pharmacogenomics through shared principles of maintaining genetic variation under selection. Studies of human genetic variation in drug response parallel evolutionary investigations by seeking to explain how functional genetic diversity persists despite selective pressures [24] [25].

The field of pharmacogenomics has revealed that functional variants in drug metabolism enzymes and targets exhibit diverse distribution across ethnic groups, influencing drug efficacy and adverse reactions [25]. This parallels the lek paradox in that genetic variation persists despite the selective advantages of optimal drug response profiles. Research shows that genetic ancestry significantly influences drug response, with variants in genes like SLC22A1, HMGCR, VKORC1, and KCNJ11 showing significant differentiation across populations [25].

This connection suggests that evolutionary frameworks developed for the lek paradox may inform our understanding of human genetic diversity in medical contexts, particularly in predicting population-specific drug responses and adverse reaction risks [24] [25].

Conceptual Framework Diagram

The lek paradox, once considered a potentially fatal challenge to sexual selection theory, has instead stimulated productive research revealing multiple mechanisms maintaining genetic variation under selection. The genic capture hypothesis, supplemented by indirect genetic effects and host-parasite coevolution, provides a robust framework explaining the persistence of female choice and genetic variance in sexually selected traits.

Future research should focus on integrating genomic approaches with experimental evolution across diverse taxa, particularly to understand how different mechanisms interact in natural populations. Furthermore, the unexpected connections between evolutionary genetics and pharmacogenomics suggest potential for cross-disciplinary insights into the maintenance of functional genetic variation across biological contexts.

The resolution of the lek paradox not only advances fundamental evolutionary theory but also enhances our understanding of genetic diversity—a crucial consideration in both conservation biology and personalized medicine.

Sexual Conflict and Its Evolutionary Consequences

Sexual conflict arises from the fundamental divergence in evolutionary interests between males and females in sexually reproducing species. While males and females share most of their genome, they often have different phenotypic optima for many traits, creating intra-locus sexual conflict where a trait is prevented from evolving toward its fitness optimum in one or both sexes [26]. This conflict emerges because the sex that provides more parental investment becomes a valuable reproductive resource for the opposite sex, typically leading to male-male competition and female mate choice [27]. These differential selective pressures drive the evolution of specialized morphological, behavioral, and physiological traits that can have profound consequences for evolutionary trajectories, genomic architecture, and even speciation.

Theoretical models predict that sexual conflict can be resolved through the evolution of sexually dimorphic gene expression, allowing each sex to approach its phenotypic optimum independently [26]. However, the expression of many genes may remain sub-optimal due to unresolved tensions between the sexes, creating ongoing selective pressures that shape evolutionary outcomes. The study of asexual lineages, where such conflicts are absent, provides compelling evidence for the significance of sexual conflict in constraining evolutionary outcomes, as gene expression in parthenogenetic females of asexual lineages is no longer constrained by expression in other morphs [26].

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Forms of Sexual Conflict

Sexual conflict manifests through two primary mechanisms with distinct evolutionary consequences:

Inter-locus Sexual Conflict: Occurs when different genes in males and females create traits beneficial to one sex but costly to the other. This conflict drives sexually antagonistic coevolution, where adaptations in one sex select for counter-adaptations in the other. Examples include male traits that facilitate coercive mating and female resistance to such coercion [28].

Intra-locus Sexual Conflict: Arises when the same set of genes has different optimal values in males and females, creating a genetic tug-of-war that prevents either sex from reaching its optimum. This form of conflict maintains genetic variation and can lead to the evolution of sex-limited gene expression [26].

Manifestations Through Sexual Selection

Sexual selection operates primarily through intrasexual competition (typically male-male competition) and intersexual choice (typically female choice) [27]. These processes lead to the elaboration of traits that improve competitive ability or attractiveness, often classified as weapons or ornaments:

Sexual Weapons: Traits used by the ardent sex (typically males) to gain mating advantages through force, either in male-male competition or by coercing females. Examples include the clasper spines in cartilaginous fishes used to anchor during copulation [28] and horns or spines observed across diverse taxa.

Sexual Ornaments: Traits considered desirable by the opposite sex that evolved through mate choice. These include elaborate plumage in birds of paradise and peacocks [28]. Ornamentation is more common where strong mate choice exists, while weaponry predominates in systems with high coercive mating pressure.

Table 1: Classification of Sexually Selected Traits and Their Functions

| Trait Category | Primary Function | Evolutionary Driver | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Weapons | Intrasexual competition; Coercive mating | Male-male competition; Sexual conflict | Clasper spines in sharks; Antlers in deer |

| Sexual Ornaments | Intersexual attraction | Mate choice | Peacock tail; Bird of paradise plumage |

| Resistance Traits | Counterselection to coercion | Sexual conflict | Modified genitalia in female insects |

| Condition-Dependent Traits | Signal of quality | Both natural and sexual selection | Bright plumage dependent on parasite load |

Empirical Evidence from Model Systems

Transcriptomic Studies in Aphids

The pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) provides a powerful model for studying sexual conflict due to its unique reproductive system involving both cyclical parthenogenesis (CP) and obligate parthenogenesis (OP) lineages. Comparative transcriptomic analyses between these lineages reveal how loss of sex alters gene expression patterns:

Experimental Protocol: Transcriptome Sequencing

- Sample Collection: Collect parthenogenetic females and males from four OP lineages and parthenogenetic females, males, and sexual females from four CP lineages

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from whole bodies using standard extraction methods

- Library Preparation: Construct RNA-seq libraries using poly-A selection for mRNA enrichment

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on Illumina platform to obtain 30-50 million reads per sample

- Differential Expression: Map reads to reference genome and quantify gene expression levels; identify morph-biased genes using statistical frameworks (e.g., DESeq2)

- Lineage Comparison: Compare expression patterns of sex-biased genes between CP and OP lineages to test for masculinization/feminization [26]

Findings demonstrate that in OP lineages, where conflict between morphs is relaxed, gene expression in males tends toward the parthenogenetic female optimum [26]. Surprisingly, males and parthenogenetic females of asexual lineages overexpress genes normally found in the ovaries and testes of sexual morphs, suggesting both relaxation of selection and potential dysregulation of gene networks.

Morphological Studies in Cartilaginous Fishes

Cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) exhibit remarkable diversity in reproductive morphology attributed to sexual conflict. Their complex spectrum of reproductive modes and variation in genetic polyandry makes them ideal for studying sexual conflict consequences:

Research Observations:

- Clasper Spines: Males of many elasmobranch species possess spiny modifications to accessory terminal cartilages that function to anchor the clasper during copulation [28]. These structures show superficial similarity to morphological elaborations of male intromittent organs used to inflict unwanted mating in other taxa.

- Prepelvic Clasper Denticles: Holocephali possess modified dermal denticles covering paired prepelvic claspers that anchor to the female's ventral side during copulation [28].

- Functional Significance: These "weapons of sexual conflict" are not essential for copulation (most species lack them) and may function primarily in sexual coercion rather than reproductive efficiency [28].

Table 2: Documented Weapons of Sexual Conflict in Cartilaginous Fishes

| Taxonomic Group | Trait | Morphological Description | Presumed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scyliorhinidae (catsharks) | Clasper spines | Spiny armaments on terminal cartilages | Anchoring during copulation |

| Etmopteridae (lanternsharks) | Clasper hooks | Hook-like modifications on clasper surface | Secure positioning in female oviduct |

| Rajiform skates | Sharp clasper edges | Complex marginal cartilages with sharp edges | Spreading sperm; anchoring |

| Holocephali (chimaeras) | Prepelvic denticles | Modified dermal denticles on claspers | Anterior anchoring to female |

Molecular Mechanisms and Epigenetic Regulation

Endocrine Pathways and Epigenetic Modification

Emerging evidence indicates that epigenetic mechanisms contribute significantly to sex differences in brain and behavior, with sexually selected traits being particularly susceptible to epigenetic modification [27]. Steroid hormones, including estradiol and testosterone, program these traits during early embryonic and postnatal development through epigenetic changes:

Key Mechanisms:

- DNA Methylation: Sex steroid hormones induce sex-specific methylation patterns that regulate gene expression in neural circuits underlying sexually selected behaviors

- Histone Modification: Hormone-mediated acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation of histones create sex-specific chromatin states

- Noncoding RNA Regulation: Sexually dimorphic expression of microRNAs and other noncoding RNAs fine-tunes gene expression in response to hormonal signals

Experimental evidence indicates that endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), including bisphenol A, can interfere with these vital epigenetic pathways, disrupting the elaboration of sexually selected traits [27]. The condition-dependent expression of sexually selected traits—their responsiveness to factors like parasite load, nutrition, and stress—suggests strong epigenetic regulation that allows phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental conditions.

Gene Expression Networks

The transcriptomic study of aphids reveals that sexual conflict leaves signatures at the genomic level, particularly through the distribution of sex-biased genes. In cyclical parthenogenetic aphids, the X chromosome is enriched for male-biased genes, making it more favorable for males and creating tension with female interests [26]. This pattern aligns with mathematical models showing that conditions for invasion of sexually antagonistic mutations favorable to males are less restrictive on the X chromosome than on autosomes.

The transition to obligate parthenogenesis relaxes these conflicts, allowing gene expression to evolve toward female optima. However, the absence of recombination in OP lineages impedes the efficacy of selection, slowing the rate at which gene expression evolves toward optimal levels and potentially leading to increased expression divergence among asexual lineages over time [26].

Evolutionary Consequences and Broader Implications

Genomic and Phenotypic Evolution

Sexual conflict drives several significant evolutionary consequences:

- Rapid Coevolution: The antagonistic arms race between males and females can drive accelerated molecular evolution in reproductive proteins and genomic regions involved in reproductive processes

- Speciation: When populations diverge in how sexual conflict is resolved, reproductive isolation can occur as traits and preferences become mismatched between populations

- Maintenance of Genetic Variation: Intra-locus conflict maintains genetic variation that would otherwise be eliminated under consistent directional selection

- Genomic Architecture: Conflict can shape chromosomal organization, as seen in the enrichment of male-biased genes on the X chromosome in aphids [26]

Insights from Asexuality

The study of asexual lineages provides natural experiments for understanding sexual conflict consequences. Comparisons between sexual and asexual Timema stick insects revealed unexpected masculinization of sex-biased gene expression in asexual females, potentially reflecting shifts in female trait optima following sex loss [26]. Similarly, studies of obligate parthenogenetic aphids show how gene expression evolution follows the removal of constraints previously imposed by sexual conflict, though the absence of recombination complicates these patterns.

Research Methodologies and Technical Approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Sexual Conflict

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | Transcriptomics | Profile gene expression differences between sexes and morphs |

| Species-Specific Transcriptome Assemblies | Genomic analysis | Reference for mapping sex-biased gene expression |

| Histological Staining Reagents | Morphological studies | Visualize specialized structures (e.g., clasper spines) |

| Hormone Assay Kits | Endocrine profiling | Quantify steroid hormone levels (testosterone, estradiol) |

| Epigenetic Modification Kits | Mechanistic studies | Assess DNA methylation, histone modifications |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Functional validation | Manipulate candidate genes in model organisms |

| Clerodenoside A | Clerodenoside A, MF:C35H44O17, MW:736.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Verbenacine | Verbenacine, MF:C20H30O3, MW:318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Molecular Pathways in Sexual Trait Development

Sexual conflict represents a fundamental evolutionary force with consequences spanning genomic architecture, phenotypic diversity, and speciation. The integration of comparative transcriptomics, morphological analysis, and epigenetic approaches has revealed how conflict between the sexes drives rapid coevolution and maintains genetic variation. Research in model systems from aphids to cartilaginous fishes demonstrates both the ubiquity of sexual conflict and the diverse solutions evolved across taxonomic groups.

Future research directions should include more comprehensive phylogenetic comparisons, functional validation of candidate genes, and increased attention to how environmental change modulates sexual conflict. Understanding these dynamics has implications beyond evolutionary biology, including conservation of endangered species and management of pest populations. The theoretical framework of sexual conflict continues to provide powerful insights into the evolutionary process and the spectacular diversity of life.

Research Methods and Translational Applications in Sexual Selection Science

The study of mate choice and competitive behaviors is a cornerstone of sexual selection theory, providing critical insights into the evolutionary mechanisms that shape reproductive strategies and fitness outcomes in animal populations. These behavioral assays allow researchers to dissect the complex interplay between pre-copulatory preferences, intra-sexual competition, and post-copulatory selection processes. By employing controlled experimental designs across diverse taxa, from invertebrate models to vertebrate species, scientists can quantify the direct and indirect fitness benefits that arise from non-random mating patterns. This technical guide synthesizes current methodologies and analytical frameworks for measuring these behaviors within the broader context of sexual selection and mating strategies research, providing researchers with robust protocols for experimental design and data interpretation.

Theoretical Framework

Foundations of Sexual Selection

Sexual selection operates through two primary mechanisms: mate competition (intrasexual selection) and mate choice (intersexual selection). Mate competition involves individuals of one sex competing for access to mating opportunities with the opposite sex, while mate choice refers to the preferential allocation of mating effort toward individuals with specific phenotypic traits [7]. These processes generate non-random mating patterns that can be quantified through carefully designed behavioral assays.

The fitness benefits of mate choice may arise through several pathways:

- Direct benefits: Increased offspring quantity or quality through superior parental investment or resources

- Indirect genetic benefits: "Good genes" that enhance offspring viability or attractiveness

- Genetic compatibility: Optimal combinations of parental genomes that maximize offspring fitness [29]

Recent research on zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) has demonstrated that pairs formed through free mate choice achieved 37% higher reproductive success than force-paired partners, primarily through behavioral compatibility rather than genetic benefits [29]. This highlights the importance of considering both genetic and behavioral mechanisms when designing mate choice experiments.

Mating Status-Dependent Choice

A critical consideration in experimental design is female mating status, as virgin and mated females often exhibit different responsiveness and choosiness. Theoretical models predict that females of polyandrous species should display mating status-dependent choice, mating relatively indiscriminately initially to ensure reproductive output, then becoming more selective in subsequent matings to "trade up" to higher-quality males [30].

However, recent experimental evidence challenges this paradigm. In Drosophila melanogaster, virgin females demonstrated similar choice patterns to mated females despite higher mating propensity, suggesting mate preference stability across mating contexts [30]. This has important implications for experimental design, as many mate choice studies exclusively use virgin females, potentially overlooking meaningful variation in mating decisions across reproductive cycles.

Experimental Models and Organisms

Established Model Systems

Table 1: Characteristics of Model Organisms in Mate Choice Research

| Organism | Mating System | Key Experimental Advantages | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster (Vinegar fly) | Polyandrous with last-male sperm precedence | Short generation time; extensive genetic tools; isofemale strain panels; controlled latency trials [30] | Mating status-dependent choice; male-male competition; sensory pathways |

| Echinolittorina malaccana (Marine snail) | Size-assortative mating | Multiple experimental designs (single, male, multiple choice); wild population comparisons; similarity-based preference quantification [31] | Size-based mate choice; experimental design comparison; natural mating pattern validation |

| Taeniopygia guttata (Zebra finch) | Socially monogamous with biparental care | Complex social behaviors; cross-fostering protocols; long-term pair bonds; individual-specific preferences [29] | Behavioral compatibility; genetic vs. parental effects; mate choice fitness consequences |

Experimental Designs and Protocols

Mate Choice Assay Configurations

Different experimental designs elicit varying aspects of mate choice behavior, with complexity ranging from simple pairwise tests to complex social environments:

Single Choice Design: A single male and female are paired to measure mating propensity and latency without competition. This design isolates female responsiveness from competitive effects but may underestimate choice strength [31].

Male Choice Design: Multiple males compete for access to a single female. This assay incorporates male-male competition while maintaining controlled female exposure, revealing interactions between intra- and intersexual selection [30] [31].

Multiple Choice Design: Multiple males and females interact in semi-natural social groups. This approach most accurately mimics wild conditions and generates the strongest mate choice signals, as demonstrated in Echinolittorina malaccana where multiple-choice experiments showed patterns most similar to natural populations [31].

Drosophila melanogaster Mate Choice Protocol

Experimental Preparation:

- Establish isofemale strains from wild-caught individuals to capture natural genetic variation [30]

- Maintain flies under standardized conditions (temperature, humidity, light-dark cycles)

- Collect virgin females using light COâ‚‚ anesthesia within 6 hours of eclosion

- Age males and females separately for 3-5 days before trials to ensure sexual maturity

Virgin vs. Mated Female Trials:

- For virgin female assays: Use 3-5 day old unmated females

- For mated female assays: Virgin females are first mated with males from their own strain, then given 48 hours before remating trials [30]

- Conduct trials during peak mating activity hours (2-4 hours after lights on)

Latency Trial Protocol:

- Place single female with single male in observation chamber

- Record latency to copulation (minutes) with maximum observation period of 2 hours

- Include minimum of 20 replicates per strain combination [30]

Male Competition Trial Protocol:

- Place single female with two males from different strains in competitive arena

- Observe for 2 hours, recording which male successfully mates

- Counterbalance male strains across replicates to control for position effects

- Use large sample sizes (≥30 replicates) to ensure statistical power

Data Collection Parameters:

- Mating latency (time from introduction to copulation)

- Mating success (proportion of pairs mating)

- Mate choice (preference for specific male strains)

- Courtship behaviors (orientation, wing vibration, attempted copulation)

Zebra Finch Compatibility Protocol

Free-Choice Period:

- House 160 birds in large aviaries with equal sex ratio (80 males, 80 females)

- Allow 2 months for pair bond formation during non-breeding season