Social Network Analysis in Animal Behavior: From Wild Societies to Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Social Network Analysis (SNA) in animal behavior, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Social Network Analysis in Animal Behavior: From Wild Societies to Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Social Network Analysis (SNA) in animal behavior, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of animal social structures and their implications for health, disease transmission, and welfare. The content covers cutting-edge methodological approaches, including dynamic network modeling and AI-assisted data collection, while addressing key challenges in data definition and analysis. By comparing findings across species and validating network robustness, this review synthesizes how SNA can inform biomedical models, enhance experimental design, and contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies by leveraging naturally occurring animal social systems.

The Social Blueprint: Unraveling Animal Societies and Their Biological Significance

Core Conceptual Framework

Social network analysis (SNA) in animal behavior research provides a powerful quantitative framework for understanding the complex social structures of animal populations. This methodology translates observed behaviors into a mathematical graph, enabling researchers to move beyond dyadic interactions and analyze the broader social system. The foundational elements of any animal social network are its nodes (representing individual animals) and edges (representing the social interactions or associations between them). The entire structure is termed a social graph, which can be analyzed using a suite of metrics to quantify social structure, individual positions, and group dynamics [1] [2].

In practice, animal social networks are distinguished by three key levels of abstraction [2]:

- Theoretical Constructs: The latent social relationships of interest (e.g., dominance, affiliation, friendship), which are abstractions that cannot be observed directly.

- Interaction Networks: The level of quantifiable social interactions (e.g., grooming, aggression) used as a proxy for the theoretical construct.

- Measured Networks: The raw, observed data on social interactions, which are subject to sampling effort and error.

Defining Network Components: Nodes and Edges

Nodes (Vertices)

In animal social networks, nodes almost exclusively represent individual animals. The definition of an "individual" within a study population must be clearly delineated during the research design phase.

Operational Guidance:

- Nodes should be uniquely identifiable individuals.

- The total population (node set) should be defined by clear spatial or membership criteria relevant to the species and research question.

- In captive settings, the node set may include all individuals in an enclosure. In wild populations, it often includes all animals within a defined social group or geographical area.

Edges (Links or Ties)

Edges represent a measurable social interaction or association between two individuals. The definition of an edge is the most critical step in study design and must be precisely tailored to the biological question. Edges can be constructed in several fundamental ways [2] [3]:

- Interaction Edges: Defined by a specific, observed behavioral event (e.g., grooming, aggression, vocal exchange). These are typically directed (from actor to receiver) and may be weighted by the frequency or duration of interactions [1].

- Association Edges: Defined by spatial or temporal proximity, or shared use of a resource. Two individuals are connected if they are observed within a specified distance, or if they co-use a resource like a refuge or foraging site, potentially asynchronously [3]. These are typically undirected.

Table 1: Common Edge Definitions in Animal Social Network Research

| Edge Type | Definition | Directionality | Common Weighting | Typical Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | Observed agonistic interaction (e.g., chase, bite) | Directed | Frequency, intensity score | Dominance hierarchy analysis |

| Allogrooming | One individual grooms another | Directed | Duration | Affiliative relationships, social bonding |

| Spatial Proximity | Individuals within N body lengths | Undirected | Co-occurrence frequency | Group cohesion, social organization |

| Gambit of the Group | Individuals observed in the same subgroup | Undirected | Number of co-occurrences | Defining association networks in fission-fusion societies |

| Shared Resource Use | Individuals using the same resource (e.g., refuge) | Undirected | - | Disease transmission, environmental sociology [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Network Construction

Constructing a robust social network requires a standardized protocol from data collection to graph assembly. The following workflow details the primary steps for building an association-based network, a common approach in behavioral ecology.

Protocol 1: Constructing an Association Network via the "Gambit of the Group"

Objective: To map the social association network of a population based on group co-membership.

Materials:

- Focal study population

- Data recording equipment (e.g., video cameras, GPS tags, dataloggers)

- Statistical computing environment (e.g., R, Python)

Procedure:

- Behavioral Sampling:

- Conduct focal animal sampling or scan sampling across multiple sessions to record the group composition at each time point [2].

- A "group" is typically defined as individuals within a predetermined spatial threshold (e.g., 5-10 meters for primates).

- Record all unique individuals present in each observed group.

Construct a Group-by-Individual Matrix:

- Create a bipartite matrix B where rows represent sampling events/groups (

g) and columns represent individuals (i). B(g,i) = 1if individualiwas observed in groupg, and0otherwise. This creates a bipartite graph linking individuals to the groups they were observed in [3].

- Create a bipartite matrix B where rows represent sampling events/groups (

Calculate Association Strength:

- Derive a symmetric association matrix A from matrix B. A common metric is the Simple Ratio Index (SRI):

SRI(x,y) = Nxy / (Nx + Ny - Nxy)- Where

Nxyis the number of sampling events/groups in which bothxandywere observed,Nxis the number of events wherexwas seen, andNyis the number of events whereywas seen.

- Derive a symmetric association matrix A from matrix B. A common metric is the Simple Ratio Index (SRI):

Generate the Social Graph:

- Perform a one-mode projection of the bipartite graph B onto the set of individuals [3].

- In the resulting social graph, an edge exists between two individuals if their association strength (

SRI) meets or exceeds a pre-defined threshold, or the edge can be weighted by theSRIvalue itself.

Protocol 2: Constructing an Interaction Network from Focal Sampling

Objective: To map a directed social network based on observed behavioral interactions.

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Conduct standardized focal follows on each individual in the population for equal durations.

- Record all instances of a pre-defined set of social behaviors (e.g., grooming, aggression, food sharing), noting the actor and receiver for each event.

Construct the Adjacency Matrix:

- Create a matrix M where rows represent actors and columns represent receivers.

- The value in each cell

M(i,j)is the frequency or total duration of the behavior initiated by individualiand directed toward individualj.

Generate the Social Graph:

- Matrix M directly defines a weighted, directed social graph. The graph can be analyzed as-is, or can be dichotomized (e.g., an edge exists if interaction frequency is above a certain threshold).

Analytical Framework and Key Metrics

Once a social graph is constructed, its properties can be quantified at the individual, dyadic, and group levels. The table below summarizes key social network metrics and their biological interpretations.

Table 2: Key Social Network Metrics for Animal Systems

| Metric | Level | Definition | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Individual | Number of direct connections a node has. | Measures an individual's gregariousness or social popularity [1]. |

| Strength | Individual | Sum of weights of edges connected to a node (weighted degree). | Measures the total intensity or frequency of an individual's social interactions. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Individual | Number of shortest paths between other individuals that pass through the focal node. | Identifies individuals that act as bridges or brokers between different parts of the network, potentially controlling information flow [1]. |

| Closeness Centrality | Individual | Average shortest path length from a node to all other nodes. | Measures how quickly an individual can interact with or access all others in the network [1]. |

| Eigenvector Centrality/PageRank | Individual | Measure of a node's influence based on the influence of its connections. | Identifies individuals connected to other well-connected individuals; a recursive measure of influence [1]. |

| Clustering Coefficient | Individual/Group | Measures the degree to which a node's neighbors are connected to each other. | Quantifies the cliquishness of local neighborhoods; high values indicate tight-knit friendship triangles [1]. |

| Network Density | Group | Proportion of possible edges that are actually present. | Measures the overall level of social connectivity in the population [1]. |

| Modularity | Group | Strength of division of a network into modules (communities). | Quantifies the presence of distinct social subgroups or communities within the larger population [1]. |

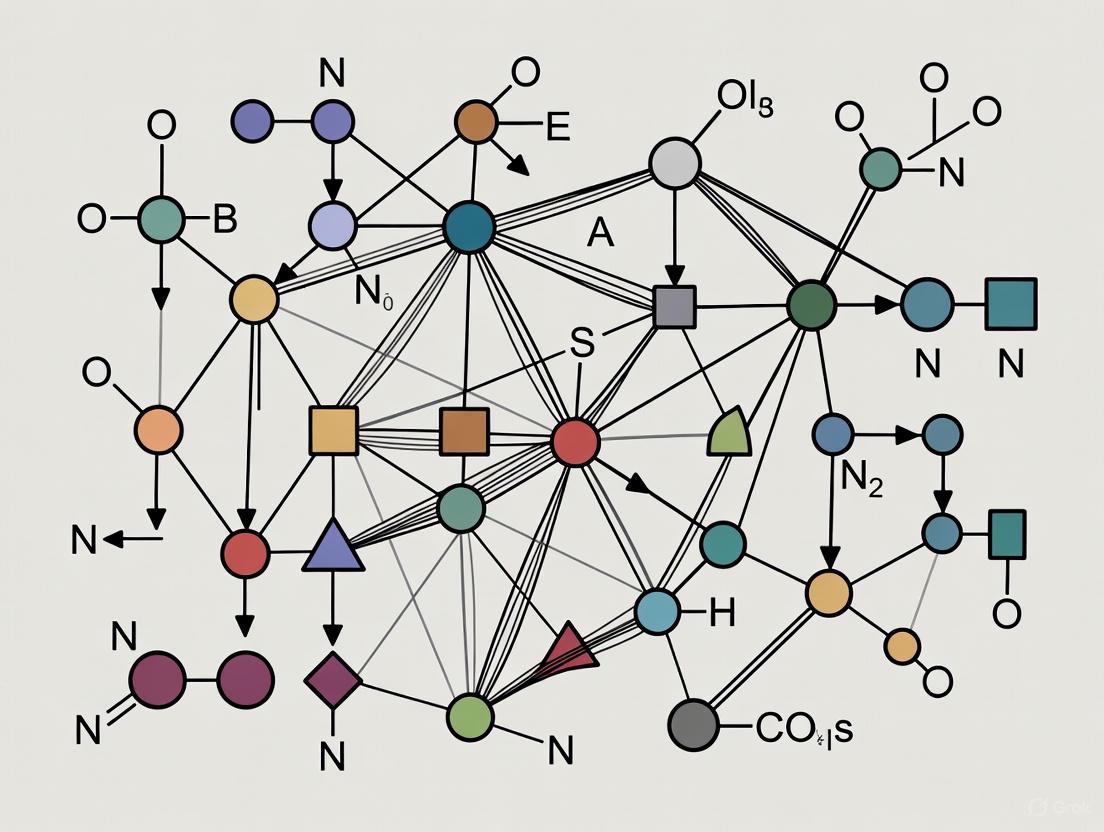

The relationships between a hypothesized driver, the collected data, and the inferred social network can be formally represented using a causal modeling framework, as shown in the following Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential analytical tools and conceptual frameworks required for modern animal social network research.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Animal Social Network Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Focal/Scan Sampling Protocol | Standardized behavioral observation | Ensures reproducible and unbiased data collection for edge definition. |

| Statistical Computing | R Programming Environment | Data manipulation, analysis, and visualization | Supported by packages like asnipe, sna, igraph, and tnet for comprehensive SNA [1]. |

| Graph Analytics | igraph Library (R, Python, C++) |

Network construction and metric calculation | Efficient implementations of algorithms for centrality, community detection, etc. [1] |

| Causal Inference | Bayesian Multilevel Models (e.g., Social Relations Model) | Estimating causal drivers of network structure | Isolates effects of individual, dyadic, and group-level features while accounting for data dependencies [2]. |

| Conceptual Framework | Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) | Formalizing causal assumptions | A graphical model to encode hypotheses and identify confounding variables [2]. |

| Graph Databases & Query | Neo4j, TigerGraph, PuppyGraph | Storing and querying complex network data | Useful for managing highly connected data and performing complex traversals [1]. |

| Crovozalpon | Crovozalpon, CAS:2406205-67-0, MF:C20H19ClF2N2O3, MW:408.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| WK692 | WK692, MF:C26H28Br2N8O5, MW:692.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Notes

This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for investigating the links between social connectivity, health, and reproductive success within the context of animal behavior research. The content is designed to support a broader thesis in social network analysis, offering researchers standardized methods to quantify social structures and their fitness consequences.

A growing body of evidence across species indicates that social connection is a fundamental determinant of health and reproductive fitness. In humans, the World Health Organization reports that loneliness is linked to an estimated 871,000 deaths annually and increases the risk of conditions like stroke, heart disease, diabetes, and depression [4]. Conversely, strong social connections can reduce inflammation, lower the risk of serious health problems, and prevent early death [4]. Parallel findings in animal models reveal that different types of social bonds—such as pair bonds, territorial neighbors, and flockmates—can have contrasting, multi-faceted effects on components of reproductive success, including clutch size, laying date, and fledgling number [5]. These relationships are often mediated by mechanisms such as reduced territorial aggression, enhanced information sharing, and cooperative defense [6].

The following sections provide a structured framework for measuring these phenomena, including standardized data collection protocols, analytical models for dynamic network analysis, and key reagent solutions for field research.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Social Connectivity on Health and Fitness Metrics

| Subject/Species | Social Connection Metric | Health/Fitness Outcome | Effect Size & Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human (Global Population) | Loneliness (Subjective feeling) | All-cause mortality | ~871,000 deaths annually; risk comparable to smoking. | [4] |

| Human (Global Population) | Social Isolation (Objective lack of connections) | Mental Health (Depression) | Twice as likely to develop depression. | [4] |

| Great Tit (Parus major) | Strength of pairmate bond | Earlier egg laying | Stronger bonds correlated with earlier laying. | [5] |

| Great Tit (Parus major) | Number of spatial associates | Clutch size | More associates correlated with smaller clutches. | [5] |

| Great Tit (Parus major) | Overall social connectedness | Number of fledglings | More-social individuals had more fledglings. | [5] |

| Seasonal Territorial Animals | Neighbor familiarity (Dear-enemy effect) | Territory establishment costs & timing of breeding | Reduces costly aggression, facilitates earlier breeding. | [6] |

Table 2: Core Components of Subjective Well-being for Measurement (OECD Guidelines)

| Component | Description | Example Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Life Evaluation | Reflective, cognitive assessment of one's life. | Satisfaction with life. |

| Affect | Feelings or emotional states. | Experience of positive/negative emotions. |

| Eudaimonia | Sense of worth, meaning, and purpose in life. | Sense that activities are worthwhile. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic Social Network Analysis using Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs)

Application: For analyzing how social networks and individual traits co-evolve over time and influence fitness outcomes [7].

Workflow:

- Data Collection: Collect longitudinal, time-ordered data on individual associations or interactions across multiple discrete time points (e.g., weeks or seasons). Data should be binary (associated/not associated) for each dyad at each time point [7].

- Model Framework: Employ SAOMs, implemented via the

RSienapackage in R, to model transitions between network states. These models treat network change as a Markov process, where the future state depends on the current state [7]. - Parameter Inclusion: Include effects at multiple levels:

- Network Structure: Endogenous effects like transitivity (friends of friends become friends) and reciprocity.

- Covariates: Individual (e.g., dominance, health status), dyadic (e.g., kinship, spatial proximity), and environmental variables [7].

- Model Fitting & Interpretation: Fit the model to test specific hypotheses about how social networks drive trait changes (e.g., health decline influencing social position) or how traits drive network changes (e.g., dominance influencing connection formation). The output estimates parameters indicating the strength and direction of these effects [7].

Protocol 2: Dissecting Multi-Level Social Bonds and Reproductive Fitness

Application: For testing how different types of dyadic relationships within a multi-level society independently and jointly shape various reproductive traits [5].

Workflow:

- Identify Bond Types: Define and collect data on distinct social layers in the study population. In great tits, this includes pair mates, breeding neighbours, winter flockmates, and spatial associates [5].

- Fitness Data Collection: Record key reproductive metrics for each individual, such as clutch size, egg-laying date, and number of fledglings.

- Spatial Control: Account for the spatial environment (e.g., population density, habitat quality) as it can confound sociality-fitness links [5].

- Statistical Modeling: Use multivariate models (e.g., GLMM) with the multiple bond types as simultaneous predictors and reproductive metrics as separate response variables. This reveals which social layers most strongly affect different fitness components [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Social Connectivity Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Animal Tags | Individual identification for constructing longitudinal social networks. | Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags, colored leg bands, or GPS loggers. |

| Automated Data Loggers | Unobtrusive, continuous monitoring of individual associations at central points. | RFID readers at feeders or waterholes to record co-occurrences [5]. |

| Social Connection Measurement Inventory | Repository of validated tools for quantifying social isolation, loneliness, and connection. | The Foundation for Social Connection's inventory lists 55+ measures with psychometric data [8]. |

R Package RSiena |

Statistical analysis of longitudinal network data using Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs). | Allows modeling of complex co-evolution dynamics between networks and behavioral traits [7]. |

| SILC Intervention Catalog | Resource for identifying existing interventions designed to foster social connection. | Catalog of solutions for addressing social isolation and loneliness; useful for designing experimental manipulations [8]. |

| OECD Well-being Guidelines | Standardized modules for measuring subjective well-being (life evaluation, affect, eudaimonia) in a comparable way. | Provides question wording, answer scales, and survey design for robust data [9]. |

| UF010 | UF010, CAS:537672-41-6, MF:C11H15BrN2O, MW:271.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ES9-17 | ES9-17, MF:C10H8BrNO2S2, MW:318.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of social network analysis in animal behavior research, social environments are not merely backdrops but active evolutionary drivers. The structure of a population—the pattern of connections that dictate interactions and information flow—can fundamentally alter the trajectory of natural selection. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for studying these selection pressures in networked populations, translating theoretical models from evolutionary graph theory and population genetics into practical experimental methodologies for biological research. The core principle is that network topology can accelerate or suppress the spread of beneficial traits, a effect empirically supported in microbial systems and predicted to influence social behaviors in animal groups [10].

Theoretical Foundation: Evolutionary Driving Forces in Networks

Evolution in a networked population is governed by the interplay of classic evolutionary forces and population structure.

- Evolutionary Driving Forces: The primary forces are mutation, natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow (migration). Their effect on genetic diversity is modulated by population structure [11].

- Natural Selection in Networks:

- Positive Selection increases the frequency of advantageous variants, potentially carrying linked, non-advantageous genes to high frequency through "genetic hitchhiking" [11].

- Negative Selection removes deleterious mutations from the population [11].

- Balancing Selection maintains multiple alleles, potentially explaining the persistence of certain behavioral polymorphisms in animal societies, akin to its role in immune-related diseases [11].

- The Topology Effect: Contrary to classic population genetics models that predict little effect of structure on fixation probability, Evolutionary Graph Theory (EGT) demonstrates that the specific arrangement of connections among individuals or subpopulations can amplify or suppress selection. This has been demonstrated experimentally, where a star network topology accelerated the spread of a beneficial mutation under low migration rates [10].

Key Experimental Findings and Data Synthesis

Empirical evidence, particularly from microbial systems, provides a controlled validation of theoretical predictions and a model for designing experiments in animal behavior.

Table 1: Quantitative Findings on Topology and Evolutionary Dynamics

| Network Topology | Migration Rate | Effect on Spread of Beneficial Mutant | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Mixed | High (e.g., 20-30%) | Faster spread than structured networks | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ciprofloxacin-resistant mutant reached higher final frequency in well-mixed vs. star topology [10]. |

| Star Network | High (e.g., 20-30%) | Suppressed spread compared to well-mixed | The resistant mutant had a significantly lower final frequency at 30% migration (χ² = 15.348, p < 0.0001) [10]. |

| Star Network | Very Low (e.g., <0.01%) | Amplified spread (transient effect) | Relative frequency of the mutant was significantly higher in the star network on Day 5 (χ² = 13.825, p = 0.0002) [10]. |

| Bidirectional Star | Low | Amplification of selection | Consistent with EGT predictions that certain topologies can increase the fixation probability of beneficial mutations [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following protocol, adapted from empirical studies on microbial metapopulations, provides a template for investigating topology-driven selection.

Protocol 1: Tracking a Beneficial Trait in a Metapopulation Network

I. Research Objective: To quantify the effect of network topology (e.g., well-mixed vs. star) on the rate of spread and fixation probability of a beneficial mutant.

II. Experimental Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural steps of this protocol.

III. Materials and Reagents. Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Model Organism | Subject of study; should be tractable and have a measurable beneficial trait. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (for antibiotic resistance) [10]. Alternative: social animals with observable behaviors. |

| Selective Agent | Applies uniform selective pressure across the network, favoring the beneficial mutant. | Sub-inhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin (e.g., providing ~20% fitness advantage) [10]. |

| Growth Medium | Supports population growth during selection phases. | Standard liquid or solid growth medium (e.g., LB broth for bacteria). |

| Diluent / Migration Buffer | Medium for serially transferring and diluting populations during dispersal events. | Physiological saline or fresh growth medium without selective agent. |

IV. Step-by-Step Procedure.

Network Construction:

- Design the physical implementation of the metapopulation network. For a 4-deme star network, use one central "hub" and three satellite "leaf" populations.

- The well-mixed control should consist of demes with all-to-all connectivity at each dispersal event.

Founder Population and Inoculation:

- Grow cultures of the wild-type and isogenic beneficial mutant (e.g., a ciprofloxacin-resistant strain,

cipR). - Inoculate all demes (hub and leaves) with the wild-type at a standard density.

- Introduce the beneficial mutant at a low, defined initial frequency (e.g., 1:1000) into a single, predefined location (e.g., one leaf population) to mimic a novel mutation's origin.

- Grow cultures of the wild-type and isogenic beneficial mutant (e.g., a ciprofloxacin-resistant strain,

Selection Phase and Serial Transfer:

- Incubate all populations under defined conditions (e.g., 37°C with shaking) for a fixed growth period (e.g., 1 day).

- The growth medium in all demes contains the selective agent at a concentration calibrated to provide a known fitness advantage to the mutant.

Controlled Dispersal:

- Following the selection phase, implement dispersal according to the network topology and predefined migration rate (m).

- For a star network with 10% migration:

- Hub to Leaf: For each leaf, combine a volume of the hub culture representing 10% of the leaf's final volume with 90% of the leaf's own culture.

- Leaf to Hub: Combine a volume from each leaf culture representing (10%/number of leaves) of the hub's final volume to create the new hub culture.

- Mix the samples thoroughly before transferring to fresh medium for the next growth cycle.

Monitoring and Data Collection:

- Sample each population at every transfer time point.

- Quantify the frequency of the beneficial mutant in each deme. This can be achieved by plating dilutions on selective and non-selective media or by using PCR-based genotyping techniques.

- Track the frequency over time (e.g., for 5-6 days, ~35-40 generations) to capture the dynamics before the emergence of secondary mutations.

V. Data Analysis.

- Plot the frequency of the beneficial mutant over time for each network topology.

- Compare the rate of spread (the slope of the frequency curve) between topologies (e.g., star vs. well-mixed) at different migration rates using statistical tests like Chi-squared tests on final frequencies or generalized linear mixed models on the full time series data [10].

- The experiment provides a proxy for fixation probability; a faster rate of spread indicates a higher probability of fixation.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Structural Diversity in Observed Network Populations

For studies involving longitudinal observation of animal social networks, this protocol uses modal network analysis to identify major structural regimes that may impose different selection pressures.

I. Research Objective: To compress a temporal series of observed social networks (e.g., from animal tracking data) into a minimal set of representative "modal" network structures and identify shifts between them.

II. Methodology:

- Data Input: A population of S network samples (adjacency matrices) observed over time on the same fixed set of nodes (individual animals).

- Clustering and Mode Identification: Apply a nonparametric method based on the minimum description length (MDL) principle to automatically:

- Determine the optimal number of representative networks, K.

- Assign each observed network sample to one of K clusters.

- Identify a single, sparse representative ("modal") network for each cluster that best explains the structures of the networks assigned to it [12].

- Interpretation: The transition points between clusters of modal networks represent potential shifts in the social environment. These shifts may correlate with ecological events (resource scarcity, predation pressure) or life-history events (mating seasons, dominance upheavals) and represent changes in the selective landscape.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Models | Microbial Metapopulations (e.g., P. aeruginosa) | High-replication, controlled testing of evolutionary dynamics in structured populations [10]. |

| Social Animals (e.g., birds, mammals) | Studying the evolution of behaviors (cooperation, communication) in naturalistic, observable social networks. | |

| Computational & Analytical Tools | Agent-Based Simulations (In silico) | Validating experimental results and exploring parameter spaces (e.g., migration rates, fitness advantages) [10]. |

| Modal Network Analysis (MDL Principle) | Identifying dominant social structures and regime shifts from longitudinal network data without pre-specifying the number of clusters [12]. | |

| Evolutionary Graph Theory (EGT) Models | Providing a theoretical framework and generating testable predictions about fixation probabilities in different topologies [10]. | |

| G-5555 | G-5555, MF:C25H25ClN6O3, MW:493.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Maytansinoid B | Maytansinoid B, MF:C36H51ClN4O10, MW:735.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Key Concepts

The conceptual relationship between network topology and evolutionary outcome is foundational. The following diagram summarizes the core findings and their relation to theoretical frameworks.

In animal behavior research, the micro-level encompasses the immediate, dyadic interactions between individual animals, such as grooming, aggression, foraging, and communication exchanges [13] [14]. These individual behavioral events form the fundamental building blocks of social structure. In contrast, the macro-level represents the emergent, population-scale patterns that arise from these cumulative interactions, including social organization, information flow pathways, and collective behavior phenomena [14]. This hierarchical relationship—where micro-level processes generate macro-level structures—forms the core investigative focus of social network analysis (SNA) in behavioral ecology [13].

Social network analysis provides both the theoretical framework and methodological toolkit to quantify how repeated local interactions among individuals give rise to global population structures [13] [15]. By mapping these connection patterns, researchers can identify key individuals who disproportionately influence group dynamics, trace potential pathways for disease transmission, and understand how social innovations spread through animal populations [15]. The application of SNA in animal behavior research has revealed valuable insights into the relationship between individual behavior and emergent population-level patterns across diverse species, from primates to ungulates to social insects [13].

Theoretical Framework: Connecting Micro-Behaviors to Macro-Structures

Foundational Concepts in Social Network Analysis

Table 1: Core Social Network Analysis Concepts and Their Applications in Animal Behavior Research

| Concept | Definition | Micro-Level Manifestation | Macro-Level Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct connections an individual maintains | Frequency of pairwise interactions | Identification of social hubs; potential super-spreaders in disease transmission |

| Network Density | Proportion of possible connections that actually exist | Rate and diversity of interactions across all possible dyads | Group cohesion and social resilience; higher density facilitates rapid information spread |

| Betweenness Centrality | Extent to which an individual connects otherwise disconnected groups | Individual movement between social subgroups | Structural bottlenecks or bridges for information/resource flow between communities |

| Modularity | Degree to which network divides into distinct subgroups | Preferential association within vs between subgroups | Population factionalization affecting cultural differentiation and genetic structuring |

| Path Length | Average number of steps between any two individuals | Efficiency of direct and indirect information transfer | Overall connectivity and integration of the social system |

The theoretical underpinning of micro-macro integration in animal social networks draws from sociological foundations, where macro-level processes approach social life as it exists within broader systems and institutional structures, while micro-level processes focus on interpersonal and interactional exchanges [14]. In animal contexts, these "institutions" represent evolved social conventions and ecological constraints that shape individual decision-making. The network representation chosen by researchers—whether dyadic, bipartite, multigraph, or higher-order networks—fundamentally shapes which micro-macro relationships can be detected and how they are interpreted [13].

Analytical Approaches for Micro-Macro Integration

The methodological challenge in linking micro-interactions to macro-structures lies in developing analytical approaches that accommodate the non-independence of social data—where individual relationships constitute the fundamental unit of analysis rather than independent observations [15]. Advanced SNA methods address this through:

- Multilevel network modeling that simultaneously examines individual attributes, dyadic relationships, and group-level properties

- Temporal network analysis that tracks how micro-level interaction changes propagate to alter macro-structure over time

- Network diffusion models that simulate how behaviors, pathogens, or information spread through observed connection pathways

- Stochastic actor-oriented models that examine how network position influences individual behavior while individual behavior simultaneously shapes network structure [15]

These approaches allow researchers to move beyond simple network description toward causal inference about how specific interaction patterns at the micro-level generate observable macro-structures, and how those emergent structures subsequently constrain or enable future interactions [13] [15].

Application Notes: Practical Implementation in Behavioral Research

Data Collection Protocols for Interaction Mapping

Table 2: Data Collection Methods for Capturing Micro-Level Interactions in Animal Systems

| Method | Protocol Description | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Animal Sampling | Continuous recording of all interactions of a predetermined individual for a set period | Complete interaction profiles for centrality measures | Labor-intensive; may miss simultaneous interactions |

| All-Occurrence Sampling | Recording all instances of specific behaviors across entire group | Rare but important behaviors (aggression, copulation) | May overrepresent conspicuous individuals |

| Proximity Loggers | Automated recording of individuals within predetermined distance | Large groups; cryptic species; continuous data | Equipment cost; distance may not equal interaction |

| Video Tracking Systems | Automated extraction of movement and interaction from video | High-resolution temporal data; small organisms | Processing complexity; environmental constraints |

| Genetic Methods | Inferring relationships through kinship analysis | Historical interactions; cryptic species | Indirect measure; may not reflect current interactions |

Standardized data collection protocols must be tailored to the research question and species. For whole-network studies—which capture all members of a defined group—researchers must establish clear observational boundaries and consistent operational definitions of interactions [15]. The protocol should specify:

- Definition of social connection: Determine whether interactions will be directed (A grooms B) or undirected (A and B are associated), and weighted (frequency/duration) or unweighted (present/absent) [15]

- Sampling intensity: Establish sufficient observation hours to capture representative interaction patterns while avoiding sampling artifacts

- Inter-observer reliability: Implement calibration sessions to ensure consistent coding across research team members

- Ethological relevance: Ensure defined interactions have biological significance for the study species

For longitudinal studies, maintain consistent protocols across time periods while allowing for necessary adaptations as animal groups change composition. Document all protocol modifications to ensure comparability across sampling periods.

Data Structuring for Network Analysis

Proper data structuring is fundamental for effective network analysis. Tabular data should be organized with rows representing observations and columns representing variables [16]. For network data, this typically involves two primary structures:

- Edge lists: Each row represents a relationship between two individuals, with columns for source, target, and relationship attributes (weight, type, context)

- Attribute data: Each row represents an individual, with columns for individual characteristics (sex, age, rank, personality measures) that may influence network position

Maintain clear data granularity where each row represents a single, non-aggregated observation [16]. This preserves the micro-level interaction data necessary for constructing accurate macro-level networks. Implement unique identifiers for each individual to ensure consistent tracking across observations and analyses [16].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Key Research Questions

Protocol 1: Mapping Information Flow Networks

Objective: Quantify how novel information spreads from individuals to populations through existing social networks.

Materials:

- Focal species with established social groups

- Novel foraging task or puzzle box requiring innovation

- Automated tracking system or video recording equipment

- Social network analysis software (ORA, UCINET, or R packages)

Procedure:

- Baseline network mapping: Conduct pre-experiment observations to construct baseline social networks using association, grooming, or proximity data

- Seeding innovation: Introduce trained demonstrators (or allow spontaneous innovation) at specific network positions determined by pre-calculated centrality measures

- Diffusion tracking: Record the spread of behavioral innovation through the group with continuous monitoring

- Network comparison: Compare pre- and post-diffusion networks to identify structural changes resulting from information spread

- Pathway analysis: Use network metrics (degree, betweenness, closeness centrality) to predict adoption timing and spread patterns

Analysis:

- Calculate diffusion rate as number of new adopters per time unit

- Map transmission pathways using network connection data

- Model social influence using temporal autocorrelation methods

- Test for social learning using network-based diffusion analysis

Information Diffusion Network

Protocol 2: Quantifying Social Structure Stability

Objective: Measure how micro-level interaction patterns maintain or transform macro-level social structure across temporal scales.

Materials:

- Longitudinal observational data from multiple time periods

- Social network analysis software with temporal analysis capabilities

- Environmental monitoring equipment to record ecological covariates

Procedure:

- Temporal sampling: Collect network data across multiple time points (daily, seasonally, annually) using consistent protocols

- Network construction: Build separate networks for each time period using identical interaction criteria

- Stability metrics: Calculate network-level stability measures (Matrix Correspondence, Mantel tests) between consecutive time periods

- Node-level persistence: Measure individual consistency in network position across time

- Environmental correlation: Test associations between environmental variables and network stability metrics

Analysis:

- QAP regression to test environmental effects on network structure

- Temporal autocorrelation of individual network positions

- Stochastic actor-oriented models to identify micro-level rules driving structural change

- Network visualization to illustrate structural persistence or reorganization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Animal Social Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Automated tracking system (e.g., RFID, GPS) | Continuous proximity/association data | Essential for large groups; provides high-resolution temporal data |

| Data Collection | Behavioral coding software (e.g., BORIS, Observer XT) | Standardized behavioral quantification | Enables reliable inter-observer reliability; facilitates complex ethograms |

| Network Analysis | SNA software packages (e.g., UCINET, ORA, R packages) | Network construction, visualization, and metric calculation | ORA preferred for dynamic networks; R provides greater analytical flexibility |

| Statistical Analysis | Specialized network tests (MRQAP, ERGM, SABM) | Hypothesis testing with non-independent data | Accounts for network autocorrelation; essential for valid inference |

| Visualization | Network graphing tools (e.g., NetDraw, Gephi, igraph) | Visual representation of social structure | Critical for pattern detection and result communication |

| Mps1-IN-4 | Mps1-IN-4, MF:C26H31F3N6O2, MW:516.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CC-885 | CC-885, CAS:1010100-07-8, MF:C22H21ClN4O4, MW:440.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Analytical Framework: From Raw Data to Ecological Interpretation

Data Processing Workflow

The transformation of raw behavioral observations into quantitative network metrics follows a structured pipeline:

- Data cleaning: Remove observational artifacts and ensure consistent individual identification

- Matrix construction: Convert interaction observations into adjacency matrices (individuals × individuals) with connection weights

- Network visualization: Create initial graphs to identify obvious patterns and potential data issues

- Metric calculation: Compute relevant network metrics at individual, subgroup, and whole-network levels

- Statistical testing: Implement appropriate null models to identify significantly non-random patterns

- Ecological interpretation: Relate network patterns to biological processes and ecological contexts

Analytical Workflow

Statistical Considerations for Network Data

The non-independent nature of network data requires specialized analytical approaches. Standard statistical tests that assume independence of observations produce inflated Type I errors when applied to network data [15]. Appropriate methods include:

- Multiple Regression Quadratic Assignment Procedure (MRQAP): Permutation-based method that maintains network structure while testing attribute relationships

- Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs): Probability models that test whether observed network structures occur more frequently than expected by chance

- Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs): Longitudinal models that examine co-evolution of networks and individual attributes

- Network Cross-Correlation Functions: Temporal methods that identify lead-lag relationships in dynamic networks

Model selection should be guided by research question, data structure, and underlying assumptions. Each method has specific requirements regarding network size, distribution, and missing data that must be addressed during study design and data collection phases.

Interpretation Guidelines: Bridging Micro-Macro Divides

Effective interpretation of animal social network analyses requires careful consideration of the relationship between micro-level mechanisms and macro-level patterns. Researchers should:

- Distinguish structure from function: Similar network structures can emerge from different interaction processes and serve different functions

- Consider multiple temporal scales: Micro-level interactions may have delayed effects on macro-structure that are not immediately apparent

- Account for ecological context: The same interaction pattern may have different consequences in different environments

- Acknowledge methodological constraints: Sampling intensity, operational definitions, and analytical choices all influence detected patterns

The explanatory power of social network analysis in animal behavior lies in its capacity to reveal how simple, local interaction rules generate complex population-level phenomena—and how those emergent structures subsequently feed back to shape individual behavioral opportunities and constraints [13] [14]. This iterative relationship between micro-level agency and macro-level structure represents the central theoretical contribution of network approaches to behavioral ecology.

Social network analysis (SNA) has become a fundamental tool in infectious disease ecology for quantifying contact patterns among individuals that influence pathogen spread [17]. In a network approach, the epidemiological units of infection (e.g., individuals, herds, farms) are defined as nodes, and these are inter-linked according to who is in contact with whom, where contact is assumed to represent transmission opportunities between two nodes [17]. Theoretical work has repeatedly demonstrated that incorporating contact pattern heterogeneity into epidemiological models can substantially alter model predictions, and empirical studies confirm that network connectivity influences an individual's risk of acquiring an infection [17].

A foundational question that often goes unaddressed is how to determine whether an observed pattern of cases is consistent with pathogen spread through an observed network presumed to represent potential transmission pathways [17]. Such validation is critical for developing accurate predictive models of pathogen spread [17]. These dynamic networks are fundamental aspects of an animal's environment, creating selection on behaviors and other traits, with applications ranging from disease epidemiology to the dynamics of group formation [7].

Key Analytical Frameworks and Statistical Tests

The Network k-Test for Epidemiologic Relevance

The network k-test is a novel permutation-based procedure designed to determine whether an observed contact network has epidemiologic relevance for a specific pathogen [17].

- Procedure: The k-statistic is defined as the mean number of cases observed to occur within one step (i.e., direct contacts) of an infected case in the network [17].

- Significance Testing: The observed k-statistic is compared to a permuted distribution of k-statistics generated by randomly re-allocating case locations within the network (node-label swapping) [17].

- Interpretation: A significantly high k-statistic (p < 0.05) suggests that the occurrence of cases results from pathogen propagation through network links, indicating the network's epidemiologic relevance [17].

This method is particularly powerful because it considers the global clustering pattern of cases within the network and is robust to missing data and a lack of temporal information [17].

Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs) for Dynamic Networks

While many ecological network analyses are static, SAOMs provide a framework for analyzing network dynamics [7].

- Purpose: SAOMs model gradual changes in networks and individual traits across discrete time points using hidden Markov models, allowing researchers to examine how social and non-social processes drive each other [7].

- Data Structure: These models typically use binary network data (associating or not) at each time point, with the duration of time periods determined by the study system and research questions [7].

- Application: SAOMs are individual-based models that can include effects and covariates for individuals, dyads, and populations (constant or variable), making them suitable for a wide range of ecological and evolutionary questions [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Methods for Analyzing Contact Networks in Disease Ecology

| Method | Primary Function | Data Requirements | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network k-test [17] | Tests if case pattern is consistent with transmission through observed network | Static network data, infection status | Robust to missing data (up to 50%); does not require temporal data; accounts for global clustering. | Does not model the direction or rate of spread. |

| Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs) [7] | Models network and trait co-evolution over time | Longitudinal network data across discrete time points | Allows inference of causal drivers; models complex co-evolutionary processes. | Requires high-resolution longitudinal data; performance with uncertain relationships is unclear. |

| Degree Comparison (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis) [17] | Compares connectivity of infected vs. uninfected nodes | Static network data, infection status | Simple, intuitive, and commonly used. | Cannot account for global clustering; high centrality may correlate with other susceptibility factors. |

| Logistic Regression [17] | Tests if node degree predicts infection status | Static network data, infection status | Provides a familiar statistical framework and effect sizes. | Suffers from non-independence of network data; distills network into individual-level measures. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the Network k-Test

This protocol evaluates the epidemiologic relevance of an observed social contact network for a specific pathogen using the network k-test.

1. Research Question and Hypothesis Formulation

- Question: Is the observed pattern of infected cases clustered within the observed social contact network, consistent with pathogen transmission via these contacts?

- Hypothesis: The mean number of cases within one network step of a case (k-statistic) will be significantly greater than expected if cases were randomly distributed.

2. Data Requirements and Preparation

- Network Data: An undirected social contact matrix where nodes represent individuals and edges represent potential transmission contacts.

- Epidemiological Data: A binary vector indicating the infection status (case/non-case) for each node in the network.

- Data Integration: Align network nodes and epidemiological data so that each individual has a corresponding node ID, infection status, and list of contacts.

3. Computational Procedure

- Step 1: Calculate Observed k-statistic

- For every infected node, count the number of its direct contacts that are also infected.

- Sum these counts across all infected nodes.

- Divide this sum by the total number of infected nodes to obtain the observed k-statistic [17].

- Step 2: Generate Permuted Null Distribution

- Randomly reassign the "case" status among all nodes in the network, preserving the total number of cases.

- For each permutation, re-calculate the k-statistic using the procedure in Step 1.

- Repeat this process a large number of times (e.g., 1,000-10,000 permutations) to build a null distribution of k-statistics expected under random case distribution [17].

- Step 3: Calculate Statistical Significance

- Compare the observed k-statistic to the permuted null distribution.

- The p-value is the proportion of permutations that produced a k-statistic greater than or equal to the observed value [17].

- A p-value < 0.05 indicates the network has epidemiologic relevance for the pathogen.

4. Interpretation and Reporting

- A significant result supports the hypothesis that the observed contact network represents viable pathogen transmission pathways.

- Report the observed k-statistic, the mean of the permuted distribution, the p-value, and the number of permutations performed.

- Visualize the network with cases highlighted to illustrate the clustering.

Protocol 2: Applying Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs)

This protocol outlines the steps for using SAOMs to analyze the co-evolution of social networks and disease status over time.

1. Research Question and Hypothesis Formulation

- Question: Do current social connections predict future infection status, or does current infection status predict changes in social connections?

- Hypothesis: Network structure and node attributes (like infection status) co-evolve, with each influencing the other over time.

2. Data Requirements and Preparation

- Longitudinal Network Data: A series of network observations (e.g., association data) collected at multiple discrete time points [7].

- Node Covariates: Time-varying or constant attributes of nodes (e.g., infection status, age, sex, dominance rank) [7].

- Data Structuring: Organize data into a panel format where the network and all node attributes are recorded at each observation time point.

3. Model Specification and Fitting with RSiena

- Step 1: Define the Dependent Variable

- Specify the network that is changing over time as the primary dependent variable [7].

- Step 2: Include Network Structural Effects

- Model parameters that capture endogenous network formation processes (e.g., density, reciprocity, transitivity) [7].

- Step 3: Include Covariate Effects

- Infection Dynamics: Model infection status as a dependent behavior variable, influenced by network position and other covariates.

- Network Dynamics: Include infection status as a node covariate affecting network formation (e.g., "infected actors change their socializing behavior").

- Step 4: Model Estimation

- Use the RSiena package in R to estimate model parameters via Method of Moments [7].

- Assess model convergence and goodness-of-fit.

4. Interpretation and Reporting

- Interpret significant parameters in the context of the research question.

- A positive effect of infection status on network formation suggests the attribute influences social ties.

- A positive effect of network position on infection dynamics suggests the network influences disease spread.

- Report parameter estimates, standard errors, and convergence t-ratios.

Table 2: Power and Robustness of the Network k-test Across Different Scenarios [17]

| Scenario | Network Type | Pathogen Infectiousness | Prevalence | Power of k-test | Power of Degree Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Bernoulli | Moderate (β=0.04) | 25% | High | Lower |

| Network Structure | Scale-free | Moderate (β=0.04) | 25% | High | Lower |

| Small-world | Moderate (β=0.04) | 25% | High | Lower | |

| Modular | Moderate (β=0.04) | 25% | High | Lower | |

| Pathogen Transmissibility | Bernoulli | High (β=0.133) | 25% | Very High | Lower |

| Epidemic Size | Bernoulli | Moderate (β=0.04) | 5% | Moderate | Low |

| Bernoulli | Moderate (β=0.04) | 50% | High | Lower | |

| Missing Data | Various | Moderate (β=0.04) | 25% | Remains High (even with 50% missing) | Decreases |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Social Network Analysis in Disease Ecology

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Software Environment | Provides a comprehensive platform for statistical computing and graphics. | Core platform for implementing all analytical methods described. |

| igraph Package (R) | Software Library | Network analysis and visualization. Generation of theoretical network structures (Bernoulli, modular, etc.) [17]. | Constructing and visualizing empirical contact networks; simulating network structures for power analyses [17]. |

| RSiena Package (R) [7] | Software Library | Statistical analysis of longitudinal network data using Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs). | Modeling the co-evolution of animal contact networks and infection status over time [7]. |

| Permutation Test Algorithm | Computational Method | Generates null distributions by randomizing data under a specific hypothesis. | Implementing the network k-test to assess the epidemiologic relevance of a contact network [17]. |

| High-Resolution Tracking Data | Primary Data | Raw data on individual locations or interactions (e.g., GPS, proximity loggers). | Building the empirical contact networks used as input for k-tests or SAOMs. |

| Diagnostic Assays | Laboratory Reagent | Determines the infection status (case/non-case) of each individual in the network. | Providing the binary case status data required for the network k-test and as a covariate in SAOMs [17]. |

| A2ti-2 | A2ti-2, MF:C18H18N4O2S, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BI-0474 | BI-0474, MF:C30H37N9O2S, MW:587.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization and Data Presentation Guidelines

Effective data presentation is critical for communicating complex network relationships. Adhere to the following guidelines for creating accessible visualizations.

- Color Contrast: All diagrams and figures must meet WCAG 2.1 AA minimum contrast ratios. For graphical objects and large text, a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 is required. For standard text, a ratio of 4.5:1 is required [18] [19]. The provided color palette (

#4285F4,#EA4335,#FBBC05,#34A853,#FFFFFF,#F1F3F4,#202124,#5F6368) is designed to facilitate this. - Graphs vs. Tables: Use graphs when the message is in the shape or to reveal relationships among multiple values. Use tables for looking up individual values or when presenting precise values that involve multiple units of measure [20].

- Quantitative Data Encoding: Encode quantitative values using points, lines, or bars. For categorical subdivisions, use position or color, limiting the number of different hues to a maximum of eight for preattentive distinction [20].

From Data to Dynamics: Advanced Methodologies for Mapping Animal Social Interactions

The integration of advanced sensor technologies and artificial intelligence is revolutionizing the collection of behavioral data for animal social network analysis (SNA). These automated methods enable researchers to gather high-resolution, quantitative datasets on social interactions at scales and precision previously unattainable through manual observation [21] [22]. By capturing continuous, objective data on animal movements, identities, proximities, and interactions, these tools provide the foundational data required to construct robust and dynamic social networks, offering unprecedented insights into the ecological and evolutionary processes governing animal societies [13] [7].

The table below summarizes the primary sensor technologies employed in automated animal behavior monitoring, detailing their key applications in social network research.

Table 1: Sensor Technologies for Automated Animal Tracking and Social Behavior Analysis

| Technology | Primary Data Collected | Key Applications in SNA | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computer Vision (CV) | Animal position, pose, trajectory, and appearance from video [21] [22]. | Proximity networks, interaction detection (e.g., grooming, aggression), group movement analysis [13] [23]. | Requires clear line-of-sight; processing can be computationally intensive; performance depends on lighting and occlusion [21]. |

| Wearable Inertial Sensors | Tri-axial acceleration, rotation, and movement dynamics via accelerometers and gyroscopes [24] [22]. | Classifying specific behaviors (e.g., grazing, running), activity budgets, and inferring social states like estrus or lameness [22] [25]. | Requires animal handling for attachment; potential for device loss; data from multiple individuals must be synchronized [24]. |

| RFID | Unique animal identity at specific locations or feeders [24]. | Constructing association networks based on co-occurrence at specific resources (e.g., feeders, watering holes) [7]. | Provides data only at fixed reader points, offering sparse spatial tracks compared to CV. |

| Bioacoustic Sensors | Audible and infrasonic vocalizations [26]. | Identifying call types for communication network analysis, tracking species presence, and detecting threats like gunshots [26]. | Analysis complicated by background noise; requires sophisticated machine learning models for call discrimination [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Social Network Data Collection

Protocol: Computer Vision-Based Proximity and Interaction Networks

Objective: To automatically construct dynamic social networks based on spatial proximity and specific interactions from video data.

Materials:

- JAX Animal Behavior System (JABS) or equivalent standardized hardware [23].

- High-resolution cameras (minimum 30 fps) with appropriate field of view.

- Computational hardware (GPU recommended) for video processing.

- Software: DeepLabCut, SLEAP, or SimBA for pose estimation [23].

Procedure:

- Video Acquisition: Record subjects in their enclosure using a calibrated camera setup. Ensure uniform lighting and minimize visual obstructions to optimize tracking accuracy [21] [23].

- Animal Detection and Pose Estimation: Process video frames using a pre-trained pose estimation model (e.g., DeepLabCut, SLEAP) to identify key body parts (e.g., nose, ears, tail base, limbs) for each individual [23].

- Tracking and Identity Maintenance: Link detected poses across frames to create continuous trajectories for each animal, maintaining unique identities throughout the recording session.

- Proximity and Interaction Annotation:

- Proximity: Calculate the centroid position for each animal and compute pairwise distances between all individuals in each frame. Define a social association (an "edge") when the distance between two animals is below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 2 body lengths) [13].

- Interaction: Use a specialized classifier, trained in software like JABS-AL or SimBA, to identify specific social behaviors such as grooming, mounting, or nose-to-nose contact from the sequence of poses [23].

- Network Construction: For a given time window, create an adjacency matrix where nodes represent individuals and edges represent the frequency or duration of proximity/interactions. This matrix is the raw input for social network analysis [13] [7].

Protocol: Multi-Sensor Fusion for Holistic Behavioral Phenotyping

Objective: To integrate data from wearable accelerometers and RFID systems to link individual activity states with social association patterns.

Materials:

- Tri-axial accelerometer tags.

- RFID tags and stationary readers.

- Data synchronization unit.

- Machine learning platform for sensor fusion (e.g., Python with scikit-learn).

Procedure:

- Sensor Deployment: Fit each study animal with an accelerometer tag. Install RFID readers at strategic, resource-limited locations (e.g., feeding stations, water sources, nesting areas) [24].

- Data Collection and Synchronization: Collect continuous accelerometer data and timestamped RFID read events. Ensure all data streams are synchronized to a common clock.

- Behavioral Classification from Accelerometry: Extract features (e.g., mean amplitude, variance, signal entropy) from raw accelerometer data. Use a pre-trained machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest) to classify the data into discrete behaviors such as feeding, resting, walking, or ruminating [24] [22].

- Association Events from RFID: Define a co-occurrence event when two or more animals are detected by the same RFID reader within a short time window (e.g., 2 minutes).

- Sensor Fusion and Analysis: Fuse the classified behavior and association data to answer complex questions. For instance, analyze whether individuals exhibiting lethargic behavior (from accelerometer data) also show reduced social associations (from RFID data), which could indicate sickness. This fusion can occur at the feature level (combining data before classification) or decision level (combining results from separate classifiers) [24].

Protocol: Dynamic Social Network Analysis using Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models

Objective: To model and understand how social networks change over time and how individual traits influence network evolution.

Materials:

- Longitudinal social network data (multiple observation periods).

- R statistical software with RSiena package [7].

- Covariate data on individuals (e.g., sex, dominance rank, health status).

Procedure:

- Data Structuring: Organize your observed social networks (e.g., from Protocol 1 or 2) into a sequence of two or more discrete time points (e.g., networks observed on day 1, day 2, etc.) [7].

- Model Specification: In RSiena, specify a Stochastic Actor-Oriented Model (SAOM) that includes:

- Structural Effects: Parameters that model how the network structure itself influences change (e.g., transitivity, the tendency to form ties with "friends of friends").

- Covariate Effects: Parameters that test how individual attributes (e.g., dominance) influence the rate of change in ties or the tendency to form/retain ties.

- Network-Behavior Co-evolution: If tracking a behavioral trait over time, the model can test how the network influences the behavior and vice versa [7].

- Model Estimation: Use the

siena07function in RSiena to estimate the parameters of the model, which represent the strength and direction of the various social forces driving network change. - Model Assessment and Interpretation: Check the model for convergence and goodness-of-fit. Interpret the significant parameters to draw conclusions about the social processes that best explain the observed changes in the animal social network over time [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Automated Behavioral Monitoring

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| JAX Animal Behavior System | An open-source, integrated platform providing standardized hardware designs and software for data acquisition, behavior annotation, and classifier sharing, specifically validated on diverse mouse strains [23]. |

| DeepLabCut/SLEAP | Open-source software toolkits for markerless pose estimation of animals based on deep learning. They allow researchers to train models to track user-defined body parts from video data [23]. |

| SimBA | Open-source software for classifying defined behaviors from pose estimation data. It provides a graphical user interface for creating supervised machine learning classifiers [23]. |

| Tri-axial Accelerometer Tag | A wearable sensor that measures acceleration in three spatial dimensions. The resulting data stream is used to infer body movement, posture, and specific behaviors [24] [22]. |

| Passive Integrated Transponder System | A system comprising implanted or attached RFID tags and stationary readers. It is used for unambiguous individual identification and logging visits to specific locations [24]. |

| RSiena Software Package | A statistical package for R used to analyze the evolution of social networks using Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs), allowing for the test of hypotheses about dynamic network processes [7]. |

| Cleminorexton | Cleminorexton, CAS:2980518-93-0, MF:C24H24F4N2O4S, MW:512.5 g/mol |

| Cytosporin A | Cytosporin A, MF:C17H24O5, MW:308.4 g/mol |

Workflow and Data Integration Visualizations

Computer Vision Workflow for Social Network Analysis

The diagram below illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for deriving social networks from video data using computer vision.

Multi-Level Sensor Fusion Architecture

This diagram outlines the three primary levels of sensor fusion for integrating data from multiple sources, such as accelerometers and RFID readers.

The protocols and technologies outlined provide a robust framework for integrating automated sensor data collection with social network analysis. This synergy allows researchers to move beyond static network snapshots to model the dynamic processes that shape animal societies [7]. As these technologies continue to mature, focusing on standardization, data sharing, and multidisciplinary collaboration will be key to unlocking their full potential in advancing our understanding of animal behavior, with applications spanning from fundamental ecology to conservation and precision livestock farming [21] [24] [22].

Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs) represent a class of individual-based models designed to analyze changes in social networks over discrete time points, making them particularly valuable for ecological and evolutionary studies [7]. In animal behavior research, where social relationships fundamentally influence fitness, disease transmission, information spread, and competition, SAOMs provide a dynamic framework that moves beyond static network analysis [7]. These models treat social networks as dynamically changing environments that create selection pressures on behaviors and other traits, allowing researchers to examine how social and non-social processes drive each other and what processes govern the development of network structure [7].

The fundamental limitation SAOMs address is the "snapshot problem" in social network analysis. Traditional static networks summarize relationships over a period, ignoring how individuals change interaction patterns over time and making causal inference difficult [7]. For instance, when an infected individual shows different social behavior, static analysis cannot determine whether the infection caused behavioral changes or whether pre-existing behavior patterns caused the infection [7]. SAOMs incorporate time-ordering into analyses, providing stronger evidence for potential causal pathways by observing how processes consistently precede and lead to changes in other processes [7].

Core Principles of Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models

Foundational Assumptions

SAOMs operate under several key assumptions that define their application scope and interpretation [7] [27]:

Time as Continuous Between Observations: While data are collected at discrete panel waves (time points), the model assumes unobserved "mini-steps" occur between observations, explaining how network structures emerge gradually [27].

Markov Process: The network state at time t depends only on the state at time t-1, with no direct influence from states further in the past (e.g., t-2) [27].

Actor-Oriented Decisions: The model assumes that individuals (actors) control their outgoing ties and make changes to optimize their position based on network structure and covariates [27].

One Tie Change at a Time: The network evolves through sequential micro-steps where only one outgoing tie changes at any moment, making the process computationally tractable [27].

Homogeneous Objective Function: All actors share the same fundamental propensity for tie changes, with heterogeneity introduced through network effects and covariates [27].

Mathematical and Conceptual Framework

SAOMs model network evolution as a Markov chain, where individuals are presented with opportunities to change their outgoing ties based on rate functions and then make decisions based on objective functions and evaluation functions [7]. The model decomposes into two fundamental components:

- Rate Function: Determines how frequently each actor gets opportunities to change their outgoing ties

- Objective Function: Evaluates how attractive different network configurations are to each actor

The objective function incorporates effects representing social mechanisms (transitivity, reciprocity), actor attributes (sex, age, dominance), and environmental factors, weighted by parameters estimated from the data [7].

Table: Core Components of the SAOM Framework

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Rate Function | λ_i(Ï) | Determines how often individual i gets to change their ties; can depend on covariates |

| Objective Function | fi(β,x) = Σk βk s{ik}(x) | Evaluates network configuration attractiveness for individual i based on weighted effects |

| Evaluation Function | - | Determines probability of specific tie changes based on objective function |

| Endogenous Effects | s_{ik}(x) | Network structural effects (transitivity, reciprocity) influencing tie formation |

| Exogenous Effects | s_{ik}(x) | Individual, dyadic, or environmental covariates affecting network evolution |

SAOM Application Protocol for Animal Social Networks

Data Requirements and Preparation

Implementing SAOMs requires specific data structures and preparation steps [7] [27]:

Longitudinal Network Data: Networks must be recorded at multiple discrete time points, with the duration between observations determined by the biological process under study and data resolution [7].

Binary Network Representation: Networks are typically represented as binary (association/no association) at each time point, though valued networks can be handled with modifications [7].

Covariate Integration: The model can incorporate individual covariates (sex, dominance rank), dyadic covariates (spatial proximity, kinship), and environmental variables [7].

Data Aggregation: For event-based data (specific interactions), researchers must aggregate events into states (e.g., "individuals A and B associated 4 out of 7 days this week") [7].

Table: Data Preparation Steps for SAOM Implementation

| Step | Procedure | Considerations for Animal Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Time Scale Selection | Determine appropriate intervals between network observations | Balance behavioral relevance (e.g., daily cycles) with practical constraints |

| Network Construction | Create adjacency matrices for each time point | Define association criteria appropriate for species and research questions |

| Covariate Compilation | Organize individual, dyadic, and environmental variables | Ensure temporal alignment of covariates with network observations |

| Data Formatting | Structure data for RSiena input | Create network and covariate objects with consistent ordering of individuals |

Model Specification and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete SAOM workflow from data preparation to interpretation:

Step-by-Step Analytical Procedure

Data Import and Formatting

- Load network data for each time point into RSiena format

- Specify and scale covariates appropriately

- Create RSiena data objects using

sienaDataCreate()

Model Specification

- Specify effects based on biological hypotheses

- Include structural effects (transitivity, reciprocity)

- Include covariate-based effects (homophily, sender, receiver)

Parameter Estimation

- Use method of moments estimation procedure

- Run simulations to find parameter estimates

- Check convergence statistics and overall maximum convergence ratio

Model Assessment

- Evaluate goodness of fit using simulation-based methods

- Compare nested models using score-type tests or likelihood ratio tests

- Check for potential degeneracy issues

Interpretation

- Interpret significant parameters in biological context

- Calculate predicted probabilities for specific effects

- Consider limitations and assumptions

Essential Effects and Biological Interpretations

Structural Effects

Structural effects capture how network topology itself influences its evolution, representing social preferences and constraints [7]:

- Density/Outdegree: Basic propensity to form ties, controlling for other effects

- Reciprocity: Tendency to form mutual connections

- Transitivity: Preference for forming triangles (friends of friends become friends)

- Popularity: Tendency for some individuals to receive more ties

- Activity: Tendency for some individuals to send more ties

Table: Key Structural Effects in SAOMs for Animal Behavior

| Effect | RSiena Term | Biological Interpretation | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocity | recip |

Mutualism, cooperative investment | Testing for reciprocal altruism in grooming networks |

| Transitive Triplets | transTrip |

Closure of triads, alliance formation | Investigating hierarchical stability in primate groups |

| Three-Cycles | cycle3 |

Generalized exchange systems | Measuring cyclic dominance in conflict networks |

| Popularity (sqrt) | inPopSqrt |

Preferential attachment, status | Modeling disease spread through highly-connected individuals |

| Activity (sqrt) | outActSqrt |

Individual variation in sociality | Understanding information flow in animal collectives |

Covariate Effects

Covariate effects examine how individual or dyadic characteristics influence network dynamics [7]:

- Ego, Alter, and Similarity Effects: How individual attributes affect tie formation, maintenance, and dissolution

- Dyadic Covariates: How external relationships (kinship, spatial proximity) affect social ties

The following diagram illustrates how different effects operate within the SAOM framework:

Essential Software and Analytical Tools

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for SAOM Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RSiena | Primary R package for SAOM estimation | Requires installation from R-Forge; comprehensive documentation available |