Statistical Methods in Movement Ecology: From Animal Tracking to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the statistical frameworks used to analyze animal movement data, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Statistical Methods in Movement Ecology: From Animal Tracking to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the statistical frameworks used to analyze animal movement data, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational concepts like hierarchical movement models and Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs), details the application of methods including Resource Selection Functions (RSFs), Step-Selection Functions (SSFs), and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), addresses common analytical challenges and data integration issues, and offers a comparative validation of different modeling approaches. By linking ecological insights with biomedical research, particularly in preclinical behavioral analysis, this guide serves as a critical resource for selecting and implementing the most appropriate statistical models for specific research questions.

Deconstructing Animal Movement: From Raw Tracks to Ecological Insight

The Movement Ecology Paradigm (MEP) was formally introduced to unify the study of organismal movement by proposing an integrative framework that links the internal state, motion capacity, and navigation capacity of an individual with the external environment [1] [2]. This paradigm posits that movement paths are the outcome of the interaction between these four core components, providing a mechanistic approach applicable to all movement types and organisms [3]. The MEF aims to develop a general theory for understanding the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of all movement phenomena, moving beyond taxon-specific and specialized approaches that had previously characterized movement research [1].

The field has experienced tremendous growth, fueled by technological advancements in tracking technologies and data analysis capabilities [2]. Modern movement ecology places itself at the interface of multiple research fields including physics, physiology, data science, and ecology, leveraging massive quantities of tracking data collected at ever-finer spatiotemporal resolutions [2].

Core Components of the Movement Ecology Paradigm

Conceptual Framework and Interrelationships

The MEP framework is built upon four fundamental components that interact to shape movement paths [1] [2]:

- Internal State: The intrinsic motivation to move, encompassing all factors specific to the individual that affect its propensity to move

- Motion Capacity: The suite of traits that enables the individual to move

- Navigation Capacity: The suite of traits that enables the individual to orient its movement in space and/or time

- External Factors: All social and environmental factors that affect the movement of the individual

The interaction between these components produces movement paths that can be classified according to their functionality during an individual's life, with the sum of movements constituting the "lifetime track" of an individual [3].

Quantitative Assessment of Research Trends

An analysis of movement ecology literature from 2009-2018 reveals distinct patterns in how these components have been studied. Research has predominantly focused on the effects of external factors on movement, with motion and navigation capacities receiving comparatively less attention [2].

Table 1: Research focus on MEP components (2009-2018)

| MEP Component | Research Attention | Primary Methods | Knowledge Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Factors | High (dominant focus) | Remote sensing, environmental data layers, SSFs | Integration with other components |

| Internal State | Moderate | Accelerometers, physiological sensors, HMMs | Direct measurement of motivation |

| Motion Capacity | Low | Biomechanical modeling, movement metrics | Trade-offs with other traits |

| Navigation Capacity | Low | Experimental displacement, sensor data | Cognitive processes in wild populations |

The technological landscape has also evolved significantly, with increased use of GPS devices and accelerometers, and a majority of studies now using the R software environment for statistical computing [2]. This period has been described as a "golden era of biologging" due to the widespread diffusion of animal-borne sensors [2].

Statistical Methods in Movement Ecology

Statistical models for analyzing movement data have become increasingly sophisticated, with three mainstream approaches commonly used to relate animal movement data to environmental covariates: Resource Selection Functions (RSF), Step Selection Functions (SSF), and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [4]. Each method answers different ecological questions and requires different data resolutions.

Table 2: Comparison of statistical methods in movement ecology

| Method | Temporal Scale | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Selection Function (RSF) | Coarse-scale | Habitat selection at home range scale | Ease of implementation; broad-scale patterns | Does not account for movement autocorrelation |

| Step Selection Function (SSF) | Fine-scale | Movement and habitat selection | Accounts for movement constraints; high-resolution insights | Requires high-frequency data |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Fine-scale | Linking behavior to environmental covariates | Identifies behavioral states; handles unobserved states | Complex implementation; computational intensity |

Resource Selection Functions (RSF)

A Resource Selection Function is a widely used function that relates habitat characteristics to the relative probability of use by an animal [4]. RSFs compare observed animal locations ("used" locations) to randomly selected locations within an animal's home range ("available" locations) [4]. The RSF, (w(\mathbf{x})), is typically defined in exponential form:

$$w\left( {\mathbf{x}} \right) = {\text{exp}}\left( { \beta{1} x{1} + \beta{2} x{2} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \beta{k} x{k} } \right)$$

where (\mathbf{x}={{x}{1},\dots , {x}{k}}) denotes the values of k predictor habitat variables and ({\beta }{1}),…, ({\beta }{k}) are the associated selection coefficients [4]. In practice, coefficients are estimated using logistic regression, modeling the probability that a resource unit is used given its environmental covariates.

Step Selection Functions (SSF)

Step Selection Functions extend RSFs by incorporating movement constraints and temporal autocorrelation [4]. SSFs are particularly valuable for inferring interactions between moving individuals while accounting for environmental factors [5]. These functions model the probability of selecting a movement step based on both environmental characteristics and movement constraints, providing a more mechanistic understanding of movement decisions.

Recent research has demonstrated that neglecting physical environmental features when analyzing interactions between moving animals leads to biased inference, where inter-individual interactions are spuriously inferred as affecting movement [5]. When landscape data is unavailable, applying 'Spatial+'—a method that reduces bias from unmeasured spatial factors—can improve inference of inter-individual interactions [5].

Hidden Markov Models (HMM)

Hidden Markov Models are particularly powerful for identifying discrete behavioral states from movement data and linking these states to environmental covariates [4]. HMMs assume that an animal switches between a finite number of behavioral states, each characterized by different movement patterns, with transitions between states following a Markov process.

The advantage of HMMs lies in their ability to reveal variable associations with environmental factors across different behaviors [4]. For example, a case study on ringed seals demonstrated that HMMs can identify positive relationships between prey diversity and specific behavioral states (e.g., slow-movement behavior) that might be missed by other methods [4].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Integrated Workflow for Movement Analysis

A comprehensive approach to movement ecology research involves multiple stages from study design to statistical analysis and interpretation. The following workflow integrates technological, conceptual, and analytical components within the MEP framework.

Protocol 1: Habitat Selection Analysis using SSF

Application: Quantifying fine-scale habitat selection while accounting for movement constraints and environmental heterogeneity.

Materials and Reagents:

- GPS tracking devices (minimum 5Hz sampling rate)

- Environmental data layers (remotely sensed or field-collected)

- R statistical environment with

amt,sf, andterrapackages - High-performance computing resources for large datasets

Procedure:

- Data Preparation (Duration: 2-3 days)

- Import and clean GPS tracking data, accounting for fix rates and measurement error

- Extract environmental covariates at each observed location

- Generate available points by sampling from a movement kernel around each observed location

Step Selection Analysis (Duration: 1-2 days)

- Define movement steps and turning angles between consecutive locations

- Fit SSF using conditional logistic regression

- Include interaction terms between environmental variables and movement parameters

Model Validation (Duration: 1 day)

- Assess model fit using cross-validation

- Check for residual spatial autocorrelation

- Implement "Spatial+" approach if landscape data is incomplete [5]

Interpretation (Duration: 1 day)

- Calculate relative selection strengths for environmental covariates

- Map predicted probability of use across the study area

- Relate selection patterns to internal state hypotheses

Protocol 2: Behavioral State Estimation using HMM

Application: Identifying discrete behavioral states from movement data and linking them to environmental conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-sensor biologgers (GPS + accelerometer + magnetometer)

- Environmental data synchronized in time and space

- R statistical environment with

momentuHMMpackage - High-resolution habitat maps

Procedure:

- Data Integration (Duration: 2 days)

- Synchronize data streams from multiple sensors

- Calculate movement metrics (step length, turning angle, speed, acceleration)

- Extract environmental conditions along movement path

Model Specification (Duration: 1 day)

- Define number of behavioral states based on exploratory analysis

- Specify probability distributions for observation processes

- Design matrix for state transition probabilities

Model Fitting (Duration: 1-3 days)

- Initialize parameters using method of moments

- Fit HMM using maximum likelihood estimation

- Address local maxima by using multiple initial values

State Decoding and Interpretation (Duration: 1 day)

- Apply Viterbi algorithm for most likely state sequence

- Calculate state-dependent environmental preferences

- Relate behavioral states to internal state and external factors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for movement ecology studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Technologies | GPS loggers, Accelerometers, Radio-telemetry | Recording movement paths at various spatiotemporal scales | Quantifying habitat selection [4], identifying behavioral states [4] |

| Environmental Data | Remote sensing imagery, Habitat maps, Climate data | Characterizing external factors affecting movement | Resource selection functions [4], step selection analysis [5] |

| Statistical Software | R packages (amt, momentuHMM), Python libraries |

Implementing statistical models for movement analysis | Fitting SSFs and HMMs [4], assessing interactions [5] |

| Field Equipment | Animal handling gear, Data download stations, Weatherproof housing | Deploying and maintaining tracking equipment | Long-term movement studies, sensor deployment and retrieval |

| Trigochinin C | Trigochinin C, MF:C38H42O11, MW:674.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 9-Deacetyltaxinine E | 9-Deacetyltaxinine E, MF:C35H44O9, MW:608.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The MEP provides a powerful foundation for addressing complex ecological questions, including species responses to environmental change, conservation planning, and understanding ecological processes across scales. Future research directions should focus on better integration of all MEP components, particularly the underexplored areas of motion capacity and navigation capacity [2].

Technological advancements continue to open new possibilities, with increasingly sophisticated sensors providing direct measurements of internal state (e.g., physiological sensors) and navigation capacity (e.g., magnetometers) [2]. The integration of movement ecology with other disciplines, including human mobility science, offers promising avenues for developing more general theories of movement [2].

Methodological challenges remain, particularly in accounting for landscape heterogeneity when inferring inter-individual interactions [5] and appropriately scaling from individual movement paths to population-level consequences [3]. The continued development of statistical methods such as SSFs and HMMs, coupled with the conceptual foundation of the MEP, provides a robust framework for addressing these challenges and advancing our understanding of organismal movement.

Movement ecology has increasingly focused on deconstructing the lifetime tracks of animals into hierarchically organized segments to understand the drivers and consequences of movement across spatiotemporal scales [6]. This hierarchical path-segmentation (HPS) framework is essential for elucidating how behavior, cognition, and physiology develop in relation to environmental changes [6]. The most robustly definable segments within an individual's trajectory are its diel activity routines (DARs), which represent repeated 24-hour movement path segments anchored by a fixed-duration biological clock [7] [6]. These DARs are themselves composed of smaller-scale behavioral units, including canonical activity modes (CAMs) and fundamental movement elements (FuMEs) [6] [8].

Analyzing movement through this hierarchical lens allows researchers to bridge the gap between fine-scale biomechanical processes and broader ecological patterns, facilitating predictions about how individuals may respond to environmental changes such as climate shifts and habitat modification [7] [8]. This paper presents application notes and protocols for implementing hierarchical movement analysis, with a specific focus on the transition from Fundamental Movement Elements to diel routines, framed within statistical methods for movement ecology research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

The hierarchical framework organizes movement into discrete but interconnected levels:

Fundamental Movement Elements (FuMEs): These represent elemental biomechanical movements that serve as the basic building blocks of all movement tracks, analogous to nucleic acids in DNA sequences. Examples include individual steps, wing flaps, or fin strokes [6] [8]. In practice, FuMEs are often difficult to extract from standard relocation data alone and may require accelerometer data or video analysis for precise identification [8].

Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs): When actual FuMEs cannot be identified, StaMEs (previously called metaFuMEs) serve as statistical proxies. These are derived from the statistical properties (e.g., means, standard deviations, correlations) of short, fixed-length segments of relocation tracks, typically comprising 10-30 consecutive points [8].

Canonical Activity Modes (CAMs): These are short, fixed-length sequences of FuMEs or StaMEs that represent interpretable activities such as dithering, ambling, directed walking, or running [6] [8].

Behavioral Activity Modes (BAMs): Variable-length sequences of CAMs characterize behavioral states such as foraging, resting, or traveling. These represent characteristic mixtures of CAMs that serve specific behavioral functions [8].

Diel Activity Routines (DARs): These 24-hour movement segments represent the daily activity routines of individuals, composed of sequences of BAMs and CAMs. DARs provide a biological anchor for movement analysis due to their fixed duration [7] [6].

Lifetime Movement Phases (LiMPs): Supra-diel segments consisting of multiple DARs, such as seasonal ranges or migrations [6].

Lifetime Tracks (LiTs): The complete movement record of an individual from birth to death, comprising sequences of LiMPs [6].

Table 1: Hierarchical Levels in Movement Path Segmentation

| Level | Definition | Duration | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| FuME | Fundamental Movement Element | Variable (sub-second to seconds) | Elemental biomechanical movements |

| StaME | Statistical Movement Element | Fixed (short segments) | Statistical properties of relocation sequences |

| CAM | Canonical Activity Mode | Fixed | Sequences of FuMEs/StaMEs |

| BAM | Behavioral Activity Mode | Variable | Characteristic mixtures of CAMs |

| DAR | Diel Activity Routine | 24 hours | Sequences of BAMs/CAMs |

| LiMP | Lifetime Movement Phase | Variable (days to months) | Sequences of DARs |

| LiT | Lifetime Track | Lifetime | Sequences of LiMPs |

Analytical Framework and Workflow

The analytical workflow for hierarchical movement analysis proceeds through several interconnected stages, from data collection to the classification of diel routines.

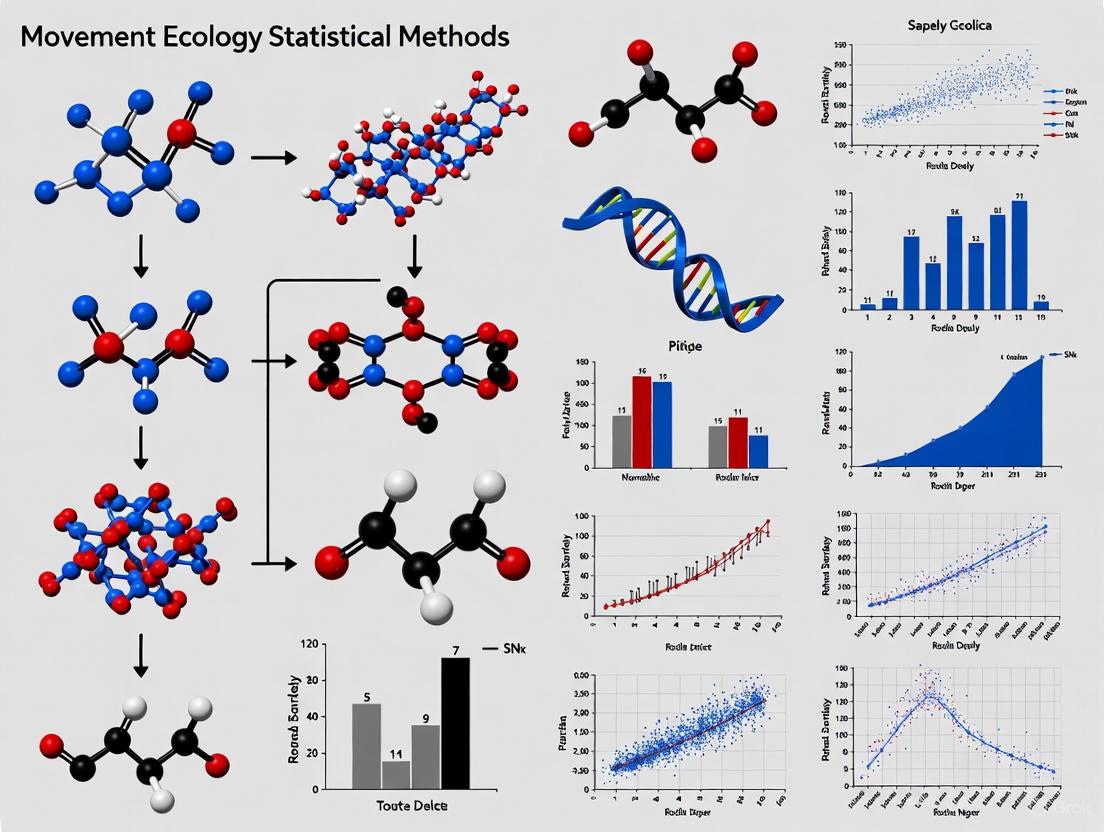

Diagram 1: Hierarchical Movement Analysis Workflow. The analytical process flows from data collection through successive stages of segmentation and classification, with hierarchical levels shown on the right.

Whole-Path Metrics for DAR Categorization

At the DAR level, geometric whole-path metrics that are relatively insensitive to data resolution are particularly useful for categorization [7]. These scalar metrics characterize the geometry of daily movement trajectories:

- Net Displacement: Distance between start and end points of the diel path

- Maximum Displacement: Maximum distance from the start point reached during the diel period

- Maximum Diameter: Largest distance between any two points in the path

- Maximum Width: Breadth of the path perpendicular to its main axis [7]

These metrics can be used in multivariate analyses such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality. In barn owl research, PC1 accounted for 86.5% of variation and represented a DAR scale factor, while PC2 accounted for 8.4% of variation and captured the "openness" of the DAR (whether animals returned to their start point) [7].

Table 2: Whole-Path Metrics for DAR Geometric Categorization

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Displacement | Distance between start and end points | Measures "openness" of the path; indicates whether animal returns to origin | Straight-line distance between first and last fix |

| Maximum Displacement | Maximum distance from start point | Indicates maximum range of movement from starting location | Maximum of distances between each fix and start point |

| Maximum Diameter | Largest distance between any two points | Represents the overall spatial extent of the daily movement | Maximum of pairwise distances between all fixes |

| Maximum Width | Breadth perpendicular to main axis | Captures the perpendicular spread of movement relative to primary direction | Computed using convex hull or similar methods |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection Requirements

High-frequency movement data is essential for robust hierarchical analysis. Studies cited in these search results collected data at frequencies ranging from sub-seconds to minutes [7] [9]. For DAR-level analysis, a minimum of 2-20 relocations per hour is recommended, though higher frequencies enable more detailed FuME/StaME analysis [7].

The appropriate start and end times for segmenting 24-hour DARs should be determined based on species-specific behavioral rhythms. For example, in black rhinos, 6:00 AM was identified as a better start/finish point than noon, 6:00 PM, or midnight due to reduced variation in spatial displacements [6].

DAR Categorization Protocol

Objective: To categorize diel movement paths into distinct geometric types based on whole-path metrics.

Materials:

- High-frequency movement data (minimum 2-20 relocations per hour)

- Statistical software with clustering capabilities (R recommended)

- Computing resources adequate for multivariate analysis

Procedure:

- Segment movement tracks into 24-hour periods using biologically relevant start times

- Calculate the four whole-path metrics (net displacement, maximum displacement, maximum diameter, maximum width) for each DAR

- Perform data normalization (z-scoring) of metrics to ensure equal weighting

- Conduct Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the normalized metrics

- Apply Ward clustering algorithm to the principal components

- Determine optimal cluster number using:

- Variance explanation thresholds

- Ecological interpretability

- Sufficient sample sizes per category

- Assign descriptive labels to DAR categories based on geometric properties

Application Note: In the barn owl case study, this protocol categorized 6,230 DARs into 7 distinct types: 5 closed (returning to same roost), 1 partially open (returning to nearby roost), and 1 fully open (leaving for another region) [7].

Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs) Extraction Protocol

Objective: To identify statistical building blocks of movement when FuMEs cannot be directly observed.

Materials:

- High-resolution relocation data (≥5 relocations per minute ideal)

- Computational resources for time-series analysis

Procedure:

- Extract step-length (SL) and turning-angle (TA) time series from relocation data

- Divide the track into fixed-length segments (typically 10-30 consecutive points)

- For each segment, calculate statistical properties:

- Means and standard deviations of SL and TA

- Autocorrelations at various lags

- Derived quantities (radial and tangential velocities)

- Apply clustering algorithms to the statistical vectors

- Identify cluster centroids representing distinct StaME types

- Validate StaME categories through behavioral observation where possible

Application Note: StaMEs serve as substitutes for FuMEs in hierarchical construction of movement tracks and can be classified into categories such as "directed fast movement" versus "random slow movement" elements [8].

Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Hierarchical Movement Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Software | Application in Hierarchy | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | GPS loggers, ATLAS reverse-GPS, accelerometers, camera traps | All levels | High-frequency relocation data collection, behavioral validation |

| Path Segmentation | Behavioral Change Point Analysis (BCPA), Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | CAM/BAM identification | Identifying transitions between behavioral states |

| Cluster Analysis | Ward algorithm, k-means, model-based clustering | StaME, CAM, DAR classification | Categorizing movement elements and routines |

| Multivariate Statistics | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Factor Analysis | Dimensionality reduction for DAR metrics | Identifying major axes of variation in path geometry |

| Movement Metrics | Step-length/turning-angle distributions, net displacement, maximum diameter | FuME/StaME and DAR characterization | Quantifying geometric properties of movement |

| Statistical Modeling | Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs), Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) | Testing effects of covariates on movement | Assessing influence of age, sex, environment on DARs |

| Specialized Software | R packages (amt, momentuHMM), Numerus ANIMOVER simulator | All analytical stages | Implementing specialized movement analyses and simulations |

| Dihydrotamarixetin | Dihydrotamarixetin, MF:C16H14O7, MW:318.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Paeonicluside | Paeonicluside, CAS:448231-30-9, MF:C18H24O11, MW:416.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Case Studies and Applications

Barn Owl DAR Categorization

A study of 44 barn owls (Tyto alba) in northeastern Israel demonstrated the application of hierarchical movement analysis, specifically at the DAR level [7]. Researchers employed ATLAS reverse-GPS technology to collect high-frequency movement data, then applied the DAR categorization protocol outlined in Section 4.2.

The analysis revealed that DARs were significantly larger in young owls than adults and in males compared to females, demonstrating how this approach can detect biologically meaningful patterns [7]. The study also constructed spatio-temporal distributions of DAR types for individuals and groups aggregated by age, sex, and seasonal quadrimester, identifying idiosyncratic behaviors within family groups in relation to location [7].

Elephant Diel Movement Analysis

Research on African savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana) illustrated the value of analyzing diel movement patterns in relation to environmental and social factors [9]. Using multi-year, high-resolution (hourly) GPS tracking data, researchers examined two key movement descriptors:

- Diel Displacement (DD): Daily sum of net displacements, serving as a proxy for energy expenditure

- Movement Predictability (MP): Degree of autocorrelated movement activity at diel timescales

The study found that both DD and MP increased with forage availability, but with significant interactions between forage availability and social rank, highlighting how social status influences movement strategies [9].

Baboon Diel Activity Patterns

A broad-scale camera trap study of chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) across 29 sites in Southern Africa demonstrated how diel activity patterns shift in response to environmental gradients [10]. Researchers analyzed over a million camera-trap detections to test hypotheses about thermoregulation, foraging optimization, and predation risk avoidance.

The findings revealed that baboons adjusted their diel activity patterns by avoiding midday heat but increasing dawn and night activity under predator pressure, demonstrating temporal flexibility as an adaptive strategy [10].

Integration with Statistical Habitat Models

Hierarchical movement analysis can be integrated with statistical models of species-habitat association to enhance ecological inference. Three prominent approaches include:

Resource Selection Functions (RSFs): Model the relative probability of use based on habitat characteristics, typically comparing "used" versus "available" locations [4]

Step Selection Functions (SSFs): Extend RSFs by incorporating movement constraints, analyzing habitat selection conditional on the animal's previous location [4]

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): Relate discrete behavioral states to environmental covariates, allowing investigation of how habitat associations vary with behavioral modes [4]

Each method offers distinct advantages for different levels of the movement hierarchy, with HMMs being particularly well-suited for analyzing CAMs and BAMs in relation to environmental factors.

Hierarchical movement analysis from FuMEs to diel routines provides a powerful framework for understanding animal movement across spatiotemporal scales. The protocols and applications outlined here offer researchers a structured approach for implementing this framework in ecological research. By decomposing movement into hierarchically organized elements, researchers can bridge fine-scale biomechanical processes with broader ecological patterns, ultimately enhancing predictions of how animals respond to environmental change.

Introducing Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs) as Building Blocks for Path Segmentation

Core Concept and Hierarchical Framework

Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs) are a novel analytical construct that serves as the smallest achievable statistical building blocks for the hierarchical decomposition and synthesis of animal movement paths. In reality, animal movement paths are a concatenation of fundamental movement elements (FuMEs), such as a single step or wing flap. However, these are generally not extractable from standard relocation time-series data (e.g., GPS fixes). StaMEs are proposed as a practical substitute, derived from the statistical properties of short, fixed-length track segments [8] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical framework for path segmentation, from raw data to complex behavioral routines.

This framework allows researchers to dissect real movement tracks and generate realistic synthetic ones, providing a general tool for testing hypotheses in movement ecology, such as evaluating an individual's response to landscape changes or identifying unusual stress [8].

Quantitative Framework and Data Presentation

StaMEs are generated by computing statistics for short, fixed-length segments of a movement track from which step-length (SL) and turning-angle (TA) time series have been extracted. The statistics of these variables for each segment form a vector that can be clustered into different StaME types [8] [11].

Table 1: Key Statistical Measures for Characterizing StaMEs

| Measure Category | Specific Metrics | Computational Description |

|---|---|---|

| Central Tendency | Mean SL, Mean TA | Average values of step-lengths and turning angles within the fixed-length segment. |

| Dispersion | Standard Deviation of SL, Standard Deviation of TA | Variance in movement pace and directionality within the segment. |

| Temporal Correlation | SL Autocorrelation, TA Autocorrelation | Measures of serial dependence, indicating persistence in speed or direction. |

| Derived Quantities | Radial Velocity, Tangential Velocity | Kinematic measures computed at each relocation point [8]. |

These segment-specific vectors are clustered, and the centroids of these clusters define a set of distinct StaME categories (e.g., "directed fast movement" versus "random slow movement") [8]. The parameters for this clustering process are crucial for the method's resolution.

Table 2: Clustering Parameters for Hierarchical Segmentation

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Description and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Segment Length (μ) | 10 - 30 relocation points [8] | Duration of the ultra-fine "base segment". Influences the granularity of StaMEs. |

| Word Length (m) | Number of base segments [11] | Number of StaMEs combined to form a "word" for CAM classification. |

| StaME Categories (n) | Determined by clustering (e.g., k-means) | Number of unique statistical movement elements identified. |

| CAM Categories (k) | Determined by clustering [11] | Number of canonical activity modes identified from "words". |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing StaME-Based Path Segmentation

Protocol 1: From Raw Tracking Data to StaME Classification

Objective: To process raw animal relocation data into classified Statistical Movement Elements (StaMEs).

Reagents & Materials:

- Input Data: A time series of animal relocations (e.g., GPS coordinates) with a consistent sampling frequency [8].

- Software: Computational environment suitable for movement data analysis (e.g., R or Python), with packages for clustering (e.g.,

stats,clusterin R) [11].

Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Import relocation data. Clean the data by removing or fixing any erroneous fixes.

- Time-Series Extraction: From the cleaned relocation data, calculate the time series of:

- Step-length (SL): The distance between consecutive relocations.

- Turning-angle (TA): The change in direction between consecutive steps [8].

- Segment Generation: Divide the SL and TA time series into short, consecutive, fixed-length segments. A segment length of 10-30 points is a common starting point [8].

- Statistical Summarization: For each segment, compute a vector of summary statistics. The core set should include, at a minimum:

- Mean(SL), Standard Deviation(SL)

- Mean(TA), Standard Deviation(TA)

- Autocorrelation(SL, lag=1)

- Clustering: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means, hierarchical clustering) to the matrix where rows are segments and columns are the summarized statistics. This will group segments with similar statistical properties.

- StaME Classification: Assign each segment a StaME type label based on its cluster assignment. The cluster centroids represent the prototypical StaMEs [8] [11].

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Segmentation into CAMs and BAMs

Objective: To aggregate StaMEs into Canonical Activity Modes (CAMs) and Behavioral Activity Modes (BAMs).

Workflow:

- CAM Formation ("Words"):

- Concatenate sequences of

mconsecutive StaMEs to form "words" [11]. - Cluster these words into

kcategories. These are the "raw" Canonical Activity Modes. - Optional Rectification: Implement a process where all word segments coded by the same sequence of

mStaMEs are identified with the same "rectified" CAM type. This enhances consistency [11]. - Behavioral Interpretation: Assign an ecological interpretation to each CAM type based on its constituent StaMEs (e.g., "fast, directed movement," "slow, random search") [8].

- Concatenate sequences of

- BAM Identification: Identify longer, variable-length segments of the track that are characterized by a specific mixture or sequence of CAMs. These segments represent coherent Behavioral Activity Modes.

- Validation: Use the percentage of reassignment errors and information theory measures (e.g., Jensen-Shannon divergence) to compare the coding efficiency of different parameter sets (

μ,m,n,k) [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Analytical Tools and Resources for StaME Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Relocation Data (GPS/ATLAS) | Primary Data | The foundational time-series of animal positions used to derive step-lengths and turning angles [8] [4]. |

| Clustering Algorithm (e.g., k-means) | Computational Method | Groups track segments based on their statistical properties to define StaME and CAM categories [11]. |

| Information Theory Measures | Analytical Metric | Quantifies the efficiency and performance of the hierarchical segmentation, aiding in parameter selection [11]. |

R Packages (e.g., amt) |

Software Tool | Provides functions for handling movement data, calculating derived quantities, and implementing related models like SSFs [4]. |

| Numerus Studio Platform | Simulation Environment | A user-friendly platform to run and explore multi-modal movement simulators like ANIMOVER_1, which can be used to test the StaME framework [8]. |

| Jangomolide | Jangomolide, MF:C26H28O8, MW:468.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Maoecrystal B | Maoecrystal B, MF:C22H28O6, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Established Movement Ecology Methods

The StaME framework is designed to complement, not replace, existing segmentation methods like Behavioral Change Point Analysis (BCPA) and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [8] [11]. It acts as a "magnifying lens" on the segments identified by these top-down methods, revealing how broader behavioral states (BAMs) are themselves composed of finer-scale canonical activities (CAMs) built from fundamental StaMEs [11]. This multi-scale, bottom-up approach provides a refined coding scheme for understanding the complex hierarchical structure of animal movement.

Linking Movement Patterns to Ecological Processes and Fitness Outcomes

Understanding the relationship between animal movement and ecology is fundamental for conservation and understanding biological processes. Statistical models transform raw movement data into insights about habitat selection, behavioral states, and ultimately, fitness outcomes. The choice of model is critical, as different methods are designed to answer specific ecological questions and operate at different spatial and temporal scales [4].

This document provides application notes and protocols for three primary statistical methods used to link movement patterns to ecology: Resource Selection Functions (RSF), Step Selection Functions (SSF), and Hidden Markov Models (HMM). We detail their implementation, required data, and interpretation, providing a toolkit for researchers to connect movement paths to underlying ecological processes.

Model Descriptions and Mathematical Foundations

Resource Selection Functions (RSF)

Description: RSFs are a widely used method to quantify habitat selection by comparing environmental conditions at locations used by an animal to those available within its home range or study area. They estimate the relative probability of use of a resource unit as a function of environmental covariates [4].

Mathematical Foundation: The RSF, (w(\mathbf{x})), is typically defined in an exponential form [4]: [ w(\mathbf{x}) = \exp( \beta{1} x{1} + \beta{2} x{2} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \beta{k} x{k} ) ] where (\mathbf{x}={{x}{1},\dots , {x}{k}}) are the values of k environmental predictor variables and ({\beta }{1}),…, ({\beta }{k}) are the selection coefficients to be estimated. In practice, these coefficients are often estimated using logistic regression. The probability that a location i is used, given its covariates ({\mathbf{x}}{i}), is modeled as [4]: [ Pr(y{i} = 1|{\mathbf{x}}{i} ) = \frac{{{\text{exp}}\left( {\beta{1} x{1,i} + \beta{2} x{2,i} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \beta{k} x{k,i} } \right)}}{{1 + {\text{exp}}\left( {\beta{1} x{1,i} + \beta{2} x{2,i} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \beta{k} x_{k,i} } \right)}} ]

Step Selection Functions (SSF)

Description: SSFs extend RSFs by explicitly incorporating movement dynamics into the analysis of habitat selection. They compare observed movement steps (the straight-line path between two consecutive locations) and their associated environmental covariates to a set of available, but not chosen, random steps originating from the same starting point [4]. This method integrates movement with habitat selection, addressing autocorrelation in the data.

Mathematical Foundation: The SSF shares a similar mathematical form with the RSF but is applied to a different conceptual framework. The likelihood of selecting a step to location i is proportional to [4]: [ w(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) = \exp( \beta{1} x{1} + \cdots + \beta{k} x{k} + \gamma{1} z{1} + \cdots + \gamma{m} z{m} ) ] Here, (\mathbf{x}) represents habitat covariates at the endpoint of the step, while (\mathbf{z}) can represent movement-related characteristics such as step length or turning angle, linking the habitat selection directly to the movement process.

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs)

Description: HMMs are a powerful tool for identifying latent (unobserved) behavioral states from sequential movement data. The model assumes that an animal's movement path is generated by a finite number of behavioral states (e.g., "foraging," "exploring," "resting"). Each state is characterized by a distinct probability distribution for movement metrics (e.g., step length, turning angle). The animal transitions between these states according to a probability matrix [12].

Mathematical Foundation: A basic HMM consists of [12]:

- State Process: An unobserved (hidden) Markov chain ({St}), where (St) denotes the behavioral state at time t. The state transition probabilities are defined by (\Gamma = (\gamma{ij})), where (\gamma{ij} = Pr(St = j | S{t-1} = i)).

- Observation Process: The observed data ({Xt}), which are the movement metrics (e.g., step lengths, turning angles). The state-dependent probability distributions are defined by (fi(x) = p(Xt = x | St = i)).

The model is fitted by maximizing the likelihood of the observations, marginalizing over all possible state sequences.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Fitting a Resource Selection Function (RSF)

Aim: To quantify second-order habitat selection (selection of a home range within the population's range) or third-order selection (selection of habitat within the home range) [4].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Start with cleaned animal relocation data ("used" locations).

- Define Availability: Generate a spatial polygon representing the area available to the animal. For third-order selection, this is typically the individual's home range, estimated using methods like Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP) or Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [4].

- Generate Available Points: Randomly sample points within the availability polygon. The number of available points per used point can vary (e.g., 10:1 is common).

- Extract Covariates: For each used and available location, extract values for all relevant environmental covariates (e.g., elevation, vegetation type, distance to water).

- Model Fitting: Fit a logistic regression model where the response variable is 1 for used points and 0 for available points. The predictor variables are the extracted environmental covariates. The estimated coefficients ((\beta)) represent the strength and direction of selection for each covariate.

- Validation: Use cross-validation techniques (e.g., k-fold) to assess the model's predictive performance. This involves repeatedly fitting the model on a subset of data and testing its prediction on the remaining data.

Protocol 2: Fitting a Step Selection Function (SSF)

Aim: To integrate movement constraints with habitat selection, providing a more mechanistic understanding of animal movement at a fine spatiotemporal scale [4].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Use regularly spaced telemetry data. Calculate step lengths (distances between consecutive points) and turning angles (changes in direction).

- Generate Control Steps: For each observed step, generate a set of random "control" steps (e.g., 10) that start from the same origin. The step lengths and turning angles for these control steps are typically drawn from distributions estimated from the observed data, representing movement options available to the animal.

- Extract Covariates: At the endpoint of every observed and control step, extract the values of the environmental covariates of interest.

- Model Fitting: Fit a conditional logistic regression model (Stratified Cox Proportional Hazards model). In this model, each stratum is a matched set consisting of one observed step and its associated control steps. This conditions the analysis on the starting point and available movement options, isolating the effect of habitat on destination choice.

- Interpretation: The resulting coefficients represent habitat selection while accounting for the underlying movement process. The model can be used to simulate movement paths in environmental space.

Protocol 3: Fitting a Hidden Markov Model (HMM)

Aim: To identify latent behavioral states from movement data and link these states to environmental conditions [12].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Start with regular time-step data. Calculate step lengths and turning angles. Step lengths are often transformed (e.g., log) to improve model fitting.

- Model Specification: Decide on the number N of behavioral states to include in the model. This can be informed by the biology of the study species and model selection criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC).

- Initialization: Provide initial values for the parameters of the state-dependent distributions (e.g., gamma for step length, von Mises for turning angle) and the state transition probability matrix. This is often a critical step, as the likelihood surface can have local maxima.

- Model Fitting: Use a numerical optimization technique (commonly the Expectation-Maximization algorithm) to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood of the observed data. The forward-backward algorithm is used to efficiently compute probabilities during this process.

- State Decoding: Use the Viterbi algorithm to determine the most probable sequence of behavioral states that generated the observed movement path.

- Post-hoc Analysis: Relate the decoded behavioral states to environmental covariates, for example, by using the states as a predictor in a subsequent statistical model to understand which habitats are associated with specific behaviors.

Comparative Analysis and Data Presentation

The choice between RSF, SSF, and HMM depends heavily on the research question, the scale of inference, and the nature of the available data. The table below provides a direct comparison to guide method selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Statistical Models in Movement Ecology

| Feature | Resource Selection Function (RSF) | Step Selection Function (SSF) | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Ecological Question | Where does an animal use space relative to what is available? | How does an animal select habitat while moving? | What behavioral states is an animal in, and how do they change? |

| Scale of Inference | Home range (2nd/3rd order selection) | Within-home range, fine-scale (3rd order) | Behavioral process scale |

| Handles Autocorrelation | Poorly; requires careful sampling of available points | Explicitly accounts for it via conditional likelihood | Explicitly models it as a state process |

| Key Input Data | Used locations, availability polygon, environmental layers | Used steps, distributions for step length & turning angle, environmental layers | Time-series of step lengths & turning angles |

| Typical Output | A map of relative probability of use | A model integrating movement and habitat selection | A sequence of predicted behavioral states |

| Key Advantage | Conceptual and implementation simplicity; broad-scale insight | Mechanistic link between movement and habitat selection | Direct inference of unobserved behaviors |

Table 2: Quantitative Data Requirements and Outputs

| Model | Minimum Required Data Points (per individual) | Typical Temporal Resolution | Key Analytical Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSF | 30-50+ locations to define use | Low to moderate (hours-days) | Selection coefficients ((\beta)), p-values, RSF map |

| SSF | 100+ locations for step distributions | High (minutes-hours) | Selection coefficients ((\beta)), movement parameters, integrated step selection map |

| HMM | 100+ locations for time-series analysis | High (minutes-hours) | State transition matrix, state-dependent distribution parameters, decoded state sequence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Packages for Movement Ecology

| Tool / Software Package | Primary Function | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Platform for all statistical analysis and modeling. | The primary environment for ecological statistics; all below are typically R packages. |

amt R Package |

Manages tracking data and fits RSFs & SSFs [4]. | Provides a coherent framework for data management, analysis, and visualization for steps and tracks. |

momentuHMM R Package |

Fits complex HMMs to animal movement data [4]. | Extends moveHMM, allows for multiple data streams and hierarchical structures [12]. |

moveHMM R Package |

Fits basic Hidden Markov Models to movement data [12]. | A user-friendly introduction to HMMs for step length and turning angle analysis. |

| GPS Biologging Devices | Collects high-resolution location data from free-ranging animals [4]. | The primary source of the movement data used in these analyses. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Manages, analyzes, and visualizes spatial data (e.g., environmental covariates). | Used to process spatial layers and extract covariate values at animal locations (e.g., using QGIS or ArcGIS). |

| Ilicol | Ilicol, MF:C15H26O2, MW:238.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ananonin A | Ananonin A, MF:C30H32O9, MW:536.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

From Patterns to Processes: Linking Movement to Fitness

The ultimate goal in movement ecology is often to understand how movement decisions translate into survival and reproductive success (fitness). The statistical models described are a critical intermediate step.

- HMMs and Energetics: Decoded behavioral states from HMMs (e.g., "foraging," "transit") can be linked to energy expenditure models. Time spent in high-cost versus high-reward states can be a proxy for fitness.

- SSFs and Resource Acquisition: SSFs can identify habitats selected during foraging, allowing researchers to model the potential caloric or nutrient intake along a movement path.

- RSFs and Population Dynamics: RSF-derived maps of high-quality habitat can be overlaid with mortality data (e.g., from predator activity or human infrastructure) to create risk landscapes. The overlap between selection and risk can directly inform survival probabilities.

By combining these movement models with demographic and environmental data, researchers can build integrated models that move beyond correlation toward a mechanistic understanding of how movement patterns in a heterogeneous environment ultimately drive fitness outcomes.

The Critical Role of GPS, Biologging, and Sensor Technologies in Data Collection

Application Notes: Current Capabilities and Research Outputs

The integration of advanced biologging technologies has fundamentally transformed movement ecology, enabling unprecedented data collection on animal behavior, physiology, and environmental interactions. The table below summarizes the quantitative capabilities and primary research outputs of modern biologging platforms.

Table 1: Quantitative Data and Research Applications of Biologging Technologies

| Technology Type | Measured Parameters | Research Applications | Example Scale/Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS & Satellite Loggers | Horizontal position (latitude/longitude), altitude, speed [13] | Migration routes, habitat selection, distribution mapping, space use [14] [4] | Global coverage; 7.5 billion location points in Movebank (2025) [13] |

| Multi-sensor Biologgers | Depth, acceleration, angular velocity, body temperature, water salinity, atmospheric pressure [13] [14] | Diving/flight behavior, energy expenditure, physiology, identification of mortality events [14] | Data on 1478 taxa; can record for >1 year [13] [14] |

| Animal-Borne Ocean Sensors | Water temperature, salinity [13] | Physical oceanography, climate change monitoring, complementing Argo float data [13] | Data volume from seals comparable to Argo floats in polar regions [13] |

| Vertical-Looking Radars (VLRs) | Flight altitude, wing movement, timing, track, size/shape of flying animals [15] | Migration ecology, stopover behavior, movement phenology [15] | Detection up to ~2 km above ground [15] |

The data collected by these technologies serve dual purposes. First, they provide direct insight into the lives of individual animals, revealing fine-scale behaviors and their drivers [16]. Second, they contribute to large-scale environmental monitoring, turning animals into mobile sensors of the world's oceans and atmospheres [13]. Platforms like the Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) have been developed to standardize, store, and share these complex datasets, facilitating collaborative research across disciplines such as ecology, oceanography, and meteorology [13]. A key feature of BiP is its Online Analytical Processing (OLAP) tools, which can calculate environmental parameters like surface currents and ocean winds from the data collected by animals [13].

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines detailed methodologies for employing biologging technologies within a movement ecology research framework, from study design to data interpretation.

Protocol 1: Investigating Species-Habitat Associations

Application: Identifying critical habitat and understanding the environmental drivers of animal space use [4].

Materials:

- Animal capture and handling equipment (e.g., traps, nets, tranquilizer darts).

- GPS biologgers with appropriate attachment method (e.g., collar, harness, glue).

- Access to environmental covariate datasets (e.g., vegetation, prey diversity, terrain).

Procedure:

- Device Deployment: Deploy GPS loggers on study animals. Record detailed metadata, including individual animal traits (species, sex, body size), device specifications, and deployment information (location, date, method) [13].

- Data Collection: Collect animal location data at a temporal resolution appropriate for the research question. For fine-scale movement, high-frequency data (e.g., every few minutes) is required [4].

- Data Standardization: Upload sensor data and metadata to a standardized platform like BiP to ensure interoperability and facilitate future reuse [13].

- Define "Used" and "Available" Locations: For each observed ("used") animal location, generate a set of "available" locations within the animal's potential movement range (e.g., its home range) at that time [4].

- Model Fitting: Relate the used and available locations to environmental covariates using an appropriate statistical model.

- Resource Selection Function (RSF): Uses logistic regression to model the relative probability of use as a function of habitat covariates [4]. The model is:

Pr(use) = exp(βâ‚xâ‚ + β₂xâ‚‚ + ... + βₖxâ‚–) / (1 + exp(βâ‚xâ‚ + β₂xâ‚‚ + ... + βₖxâ‚–))wherexare covariates andβare selection coefficients. - Step-Selection Function (SSF): Accounts for movement constraints by defining availability based on the animal's starting point and movement capabilities [4].

- Resource Selection Function (RSF): Uses logistic regression to model the relative probability of use as a function of habitat covariates [4]. The model is:

- Interpretation: Positive selection coefficients (

β) indicate a preference for a habitat feature, while negative coefficients indicate avoidance.

Protocol 2: Inferring Behavior and Fitness from Multi-sensor Data

Application: Linking movement and behavior to individual fitness outcomes like survival and reproduction [14].

Materials:

- Multi-sensor biologgers (e.g., combining GPS, accelerometer, and temperature sensors).

- Computational resources for analyzing high-resolution data.

Procedure:

- Device Deployment: Deploy multi-sensor loggers on a cohort of individuals from a study population.

- Data Collection: Collect synchronized data streams (e.g., GPS for location, accelerometry for behavior classification, temperature for physiology) over an extended period (e.g., a full annual cycle or lifetime) [14].

- Behavioral State Inference: Use statistical models like Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to classify raw sensor data into discrete behavioral states (e.g., resting, foraging, migrating). HMMs assume an animal's movement metrics (e.g., step length, turning angle) are dependent on its underlying, unobserved behavioral state [4].

- Fitness Metric Extraction:

- Reproduction: Identify recursive movements to a central place (e.g., a nest) via GPS data. Validate with accelerometer data showing characteristic nesting behaviors [14].

- Survival/Mortality: Identify mortality events from long-term stationary sensor readings, sentinel alerts from the device, or a combination of sensor data (e.g., lack of movement and a drop in body temperature) [14].

- Energetics: Derive proxies for energy expenditure (e.g., Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration - VeDBA) from accelerometer data [14].

- Spatio-Temporal Mapping: Map the inferred fitness metrics (energy expenditure, reproduction sites, mortality locations) onto environmental layers to create a "fitness landscape" and understand the environmental conditions associated with success or failure [14].

Protocol 3: Wildlife Disease Surveillance through Movement Data

Application: Early detection and management of zoonotic disease outbreaks [17].

Materials:

- GPS transmitters that allow for near-real-time data transmission.

- Access to disease outbreak databases (e.g., EMPRES-i).

- Computational tools for analyzing movement anomalies.

Procedure:

- Sentinel Species Selection: Identify and tag potential wildlife sentinel species known to be hosts or bridge hosts for pathogens of concern (e.g., waterfowl for avian influenza) [17].

- Baseline Behavior Establishment: Collect individual movement data to establish baseline behavior and social interaction patterns.

- Anomaly Detection: Monitor near-real-time data streams for behavioral anomalies predictive of disease, such as:

- Reduced movement capacity or local movements [17].

- Changes in social behavior (e.g., reduced contact rates).

- Unusual mortality events detected via sensor alerts.

- Data Integration and Alerting: Integrate movement anomaly data with other surveillance data (e.g., dead bird reports) in a unified platform. Trigger alerts for targeted sampling when anomalies are detected [17].

- Management and Modeling: Use real-time movement data to model potential disease spread and inform management actions, such as establishing movement barriers or issuing public health warnings [17].

Workflow Visualizations

Biologging Research Data Pipeline

From Sensor Data to Behavioral States

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Tools and Platforms for Biologging Research

| Tool/Platform Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Movement Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) | Data Repository & Analysis Platform | Standardized storage, sharing, and analysis of biologging data with metadata [13] | Facilitates interdisciplinary research; includes OLAP tools for estimating environmental parameters [13] |

| Movebank | Data Repository | Global database for animal tracking data [13] | Largest repository; contains 7.5 billion location points across 1478 taxa (2025) [13] |

| AniBOS | Observation Network | Global ocean observation system using animal-borne sensors [13] | Gathers physical environmental data worldwide to complement other observation systems [13] |

ctmm R package |

Statistical Software | Continuous-time movement modeling for animal tracking data [18] | Addresses autocorrelation and location error in tracking data; used for home-range analysis and habitat suitability [18] |

amt R package |

Statistical Software | Analysis of animal movement data [4] | Used for fitting Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) and Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) [4] |

momentuHMM R package |

Statistical Software | Analysis of animal movement data using Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [4] | Infers latent behavioral states from movement data [4] |

| Vertical-Looking Radar (VLR) | Field Sensor | Detects and characterizes individual flying animals [15] | Studies migration ecology and flight behavior without requiring animal capture [15] |

| Daphnilongeranin C | Daphnilongeranin C, MF:C22H29NO3, MW:355.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tenuifoliose I | Tenuifoliose I, MF:C59H72O33, MW:1309.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Core Statistical Models: RSFs, SSFs, HMMs, and Their Practical Implementation

Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) are statistical models used to estimate the relative probability of an animal selecting a resource unit based on environmental covariates, providing crucial insights into species-habitat relationships [19]. As a foundational tool in movement ecology, RSFs compare environmental attributes at locations used by animals against those available within their domain of use, enabling researchers to quantify habitat selection patterns across landscapes [20] [21]. This use-availability framework distinguishes RSFs from use-unused approaches and allows researchers to model habitat preference across multiple spatial and temporal scales—from second-order selection (home range placement in the landscape) to third-order selection (resource use within a home range) [20] [19].

The theoretical foundation of RSFs rests on the principle that animals selectively use landscape features disproportionate to their availability, indicating preference or avoidance [19]. By relating animal occurrence data to environmental predictors, RSFs facilitate understanding of critical habitat requirements, movement corridors, and species distributions—information essential for effective conservation planning and wildlife management [19]. These models have become indispensable in ecological research, particularly with the increasing availability of high-resolution tracking data from GPS and other biologging technologies [20].

Table 1: Key Definitions in Resource Selection Analysis

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Habitat | The set of environmental covariates that characterize the space an animal inhabits [19] |

| Habitat Selection | The process whereby individuals preferentially use or occupy habitats [19] |

| Habitat Availability | The accessibility, prevalence, and procurability of habitat components by animals [19] |

| Use-Availability Design | Sampling design comparing environmental conditions at used locations versus available locations [21] |

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Formulation

The RSF is typically defined as any function proportional to the probability of selection of a spatial resource unit [20]. In its most common parametric form, a RSF is an exponential function:

w(x) = exp(βâ‚xâ‚ + β₂xâ‚‚ + ··· + βₖxâ‚–) [19]

where x = {xâ‚, ..., xâ‚–} represents a vector of k environmental predictor variables, and β = {βâ‚, ..., βₖ} are the selection coefficients representing the strength and direction of selection for each covariate [19]. The exponential form ensures the RSF remains non-negative, representing a relative probability of use rather than an absolute probability.

In practice, RSF coefficients are commonly estimated using logistic regression within a use-availability framework [22] [19]. For a total of n resource units, the response variable y = {yâ‚,...,yâ‚™} consists of binary random variables where yáµ¢ = 1 indicates a used unit and yáµ¢ = 0 indicates an available unit. The probability that resource unit i is used given its environmental covariates xáµ¢ is modeled as:

Pr(yáµ¢ = 1|xáµ¢) = exp(βâ‚xâ‚áµ¢ + β₂xâ‚‚áµ¢ + ··· + βₖxâ‚–áµ¢) / [1 + exp(βâ‚xâ‚áµ¢ + β₂xâ‚‚áµ¢ + ··· + βₖxâ‚–áµ¢)] [19]

An alternative formulation represents RSFs as inhomogeneous Poisson point processes (IPPs) in geographic space, modeling the density of animal locations as a function of spatial predictors [19]. The intensity function λ(s) takes a similar exponential form:

λ(s) = exp(β₀ + βâ‚xâ‚(s) + β₂xâ‚‚(s) + ... + βₖxâ‚–(s))

where s represents a location in geographical space, xâ‚(s), ..., xâ‚–(s) are habitat variables at that location, β₀ is an intercept term, and βâ‚, ..., βₖ are the selection coefficients [19]. The IPP formulation provides a rigorous connection to spatial point process theory while yielding equivalent selection coefficients to the logistic regression approach when availability samples are large [19].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Study Design Considerations

Proper experimental design is paramount for valid RSF inference. Researchers must carefully define the sampling extent (the area within which availability is measured) and sampling grain (the resolution of analysis units) based on the ecological question and species biology [20]. The sampling extent typically corresponds to the individual's home range for third-order selection studies or the population range for second-order selection [20] [19]. Temporal matching of used and available samples is equally critical, as availability may vary seasonally or diurnally [20].

Defining availability represents one of the most challenging aspects of RSF design. Availability should reflect the area accessible to an animal within the relevant temporal frame, considering movement constraints, memory, and territoriality [19]. Common approaches include using minimum convex polygons, kernel density estimates, or time-varying Brownian bridges to characterize available space [21]. For population-level inference, researchers often employ mixed-effects models with random intercepts for individual animals to account for unbalanced sampling and correlation within individuals [22].

Data Collection Protocols

Movement data collection for RSF analysis requires careful consideration of fix rate (sampling frequency), which should align with the temporal scale of the ecological process under investigation [20]. Higher fix rates (e.g., <1 hour intervals) capture fine-scale movement decisions but increase autocorrelation, while lower fix rates may miss important habitat selection events [20]. Modern GPS collars can record locations with high accuracy (6-10m error) at programmable intervals, balancing battery life against data resolution [21].

Environmental covariate data should be collected at spatial resolutions matching or exceeding the animal location data. Remote sensing platforms (e.g., Landsat, MODIS) provide extensive spatial coverage for variables like vegetation indices, while LiDAR and aerial photography offer fine-scale terrain information [20]. Field measurements may be necessary for ground-truthed variables like food resource availability or precise vegetation composition [21]. All environmental variables should be checked for collinearity prior to analysis, with highly correlated predictors (|r| > 0.7) removed or combined [22].

Table 2: Data Requirements for RSF Analysis

| Data Type | Description | Collection Methods | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Locations | GPS coordinates of animal positions | GPS collars, VHF telemetry | Fix rate, accuracy, temporal coverage |

| Environmental Covariates | Habitat variables influencing selection | Remote sensing, field sampling | Resolution, temporal alignment with tracking data |

| Availability Samples | Random points within accessible area | GIS-based random sampling | Definition of availability domain, sample size ratio |

| Individual Metadata | Animal attributes (sex, age, etc.) | Field measurements, observation | Potential random effects in models |

Statistical Implementation Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol outlines RSF implementation using R, the most common platform for ecological modeling:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Exploration

- Import and clean animal location data, addressing any outliers or obvious errors

- Extract environmental covariate values at used locations using GIS tools or R packages like

rasterorterra - Generate available points using appropriate sampling design (typically 10-30 random points per used point within the availability domain) [21]

- Combine used and available data, creating a binary response variable (1 for used, 0 for available)

- Standardize continuous covariates to mean = 0 and SD = 1 to improve model convergence and coefficient interpretability [22]

Step 2: Model Formulation and Selection

- Develop a priori candidate models based on ecological knowledge and hypotheses

- For population-level inference with individual variation, use mixed-effects logistic regression with the

lme4package:glmer(use ~ covariate1 + covariate2 + (1|animal_id), data = data, family = binomial(link = "logit"))[22] - Compare candidate models using Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) or similar information-theoretic approaches [22] [21]

- Select the most parsimonious model balancing fit and complexity

Step 3: Model Validation and Prediction

- Validate models using k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold), calculating Spearman rank correlation between RSF scores and area-adjusted frequency of use [21]

- Generate spatial predictions of relative probability of use across the study area

- Create prediction maps visualizing habitat selection patterns

- Classify predictions into discrete bins (e.g., 5 classes of equal area) for management applications [22]

Advanced Applications and Integration with Movement Ecology

Comparison with Step-Selection Functions

Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) extend RSF methodology by explicitly incorporating movement dynamics into habitat selection analysis [20]. While RSFs typically consider habitat availability across an animal's home range, SSFs condition availability on the animal's previous location and movement capabilities, comparing each observed step (the linear segment between consecutive locations) with random steps drawn from distributions of step lengths and turning angles [20]. This approach better accounts for temporal autocorrelation and movement constraints in high-frequency tracking data [20].

SSFs are particularly valuable for studying fine-scale habitat selection during movement phases, identifying movement corridors, and understanding how animals respond to linear features like roads or rivers [20]. The SSF takes a similar exponential form to the RSF but conditions selection on the starting point: w(x|uₙ₋â‚) = exp(βx(uâ‚™)), where uâ‚™ represents the step and availability is defined conditional on the previous location uₙ₋₠[20]. Integrated Step-Selection Functions (iSSFs) further extend this framework by simultaneously modeling movement parameters and habitat selection [19].

Integration with Behavioral State Modeling

Recent advances integrate RSFs with state-space models and hidden Markov models (HMMs) to account for behavioral heterogeneity in habitat selection [20] [19]. These approaches recognize that animals may select habitats differently depending on their behavioral state (e.g., foraging, resting, migrating). By first classifying locations into behavioral states, researchers can estimate state-specific RSFs that provide more mechanistic understanding of habitat selection drivers [19].

For example, a study on ringed seals demonstrated that HMMs could reveal variable associations with prey diversity across different behaviors, with positive relationships detected only during slow-movement behavioral states [19]. This state-dependent approach often identifies different "important" areas compared to traditional RSFs, highlighting the value of incorporating behavioral context into habitat selection analyses [19].

Contact-RSF Framework for Social Species

For social species, a novel contact-RSF framework has been developed to distinguish landscape factors driving contact locations from those driving general space use [21]. This approach tests whether contacts occur randomly with respect to habitat selection or are concentrated in specific landscape features. The contact-RSF defines contact locations as "used" points and non-contact locations within home range overlaps as "available," using logistic regression to identify habitat characteristics associated with contact probability [21].

A wild pig case study demonstrated that landscape predictors (wetlands, linear features, food resources) played different roles in habitat selection versus contact processes, challenging the assumption that contact hotspots simply mirror habitat selection patterns [21]. This specialized RSF application has important implications for understanding disease transmission dynamics, social interactions, and predator-prey encounters across landscapes [21].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RSF Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS Telemetry Equipment | Hardware | Collect animal movement data | GPS collars, satellite tags |

| GIS Software | Software | Spatial data management and analysis | ArcGIS, QGIS, R spatial packages |

| R Statistical Environment | Software | Statistical modeling and analysis | R Core Team |

| amt Package | R Package | Animal movement tracking and analysis | signac, amt |

| lme4 Package | R Package | Mixed-effects modeling | glmer() function |

| Remote Sensing Data | Data | Environmental covariate layers | Landsat, MODIS, LiDAR |

| AIC Model Selection | Analytical Framework | Model comparison and selection | AICcmodavg package |

Resource Selection Functions provide a powerful statistical framework for quantifying animal-environment relationships across multiple spatial and temporal scales. When properly implemented with careful consideration of availability definition, sampling design, and model assumptions, RSFs yield robust insights into habitat selection patterns essential for ecological understanding and conservation application. The ongoing integration of RSFs with movement models (SSFs) and behavioral state models (HMMs) represents an exciting frontier in movement ecology, promising more mechanistic understanding of how animals perceive and respond to their environment across different behavioral contexts and spatial scales.

Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) are powerful statistical tools in movement ecology that integrate data on an animal's movement mechanics with its habitat selection preferences [4]. They model the probability of an animal selecting a subsequent location based on both the dynamic availability of locations given its previous movement and the environmental characteristics of those locations [23]. This method represents a significant advancement over traditional Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) by explicitly incorporating movement constraints into habitat selection analysis [4] [24]. SSFs accomplish this by comparing used steps (the actual movements between consecutive observed locations) with available steps (potential movements the animal could have made but did not) [24]. The core SSF framework can be expressed as a weighted distribution where the probability of an animal moving to a location depends on both a movement kernel and a habitat selection function [23] [24].

Fundamental Concepts and Analytical Framework

Core Mathematical Formulation

The SSF framework models the probability of finding an individual at location (s{t+1}) given its past positions (st) and (s_{t-1}) using the following relationship [23]:

[ u(s{t+1}) = \frac{\phi(s{t+1}, st, s{t-1}; \gamma)w(x(s{t+1}); \beta)}{\int{s \in G}\phi(s{t+1}, s{t}, s{t-1}; \gamma)w(x(s{t+1}); \beta)ds} ]

Where:

- (\phi) represents the animal's movement kernel, typically defined by step-length and turning-angle distributions with parameters (\gamma)

- (w) is the habitat-selection function reflecting the animal's preferences (\beta) for environmental characteristics (x) at location (s_{t+1})

- The denominator ensures proper normalization of the probability distribution [23]

In most applications, the habitat-selection function (w) is modeled as a log-linear function: (w = \exp(x^\top \beta)) [23].

Integrated Step-Selection Analysis (iSSA)

Integrated Step-Selection Analysis (iSSA) extends the basic SSF framework by jointly estimating parameters for both movement ((\gamma)) and habitat selection ((\beta)) [23]. This integrated approach enables researchers to:

- Model how animals respond to environmental heterogeneity while accounting for movement constraints

- Update initial step-length and turning-angle distributions based on estimated coefficients

- Develop fully mechanistic movement models that can simulate space use under novel conditions [23]

- Quantify landscape resistance and identify movement corridors [23]

Table 1: Key Components of Step-Selection Analyses

| Component | Description | Typical Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Movement Kernel ((\phi)) | Probability distribution of movement directions and distances | Parametric distributions (log-normal, gamma, Rayleigh) for step lengths; uniform or von Mises for turning angles [24] |

| Selection Function ((w)) | Habitat preference function | Exponential form: (w = \exp(x^\top \beta)) [23] |

| Available Steps | Control steps representing potential movement choices | Random steps generated from movement distributions [24] |

| Estimation Method | Statistical fitting procedure | Conditional logistic regression comparing used vs. available steps [23] |

Addressing Temporal Irregularity in Movement Data

The Challenge of Missing Data

A fundamental assumption of traditional iSSAs is that animal location data are collected at a constant sampling frequency, producing regular step durations [23]. However, real-world datasets frequently contain missing locations due to device limitations, with one comprehensive study reporting an average success rate of only 78% for obtaining scheduled animal locations [23]. This missingness introduces temporal irregularity that complicates analysis.

The conventional approach of using only "bursts" of regular data (sequences of locations equally spaced in time) results in substantial data loss [23]. As shown in Figure 1, a single missing location can reduce the effective sample size by three steps (the step before the gap, the step after the gap, and the turning angle at the subsequent location). With 25% missingness, the number of valid steps decreases by approximately 58% [23].