Variance Partitioning in Individual Behavior: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for applying variance partitioning to the study of individual behavior, a critical methodology for researchers and drug development professionals.

Variance Partitioning in Individual Behavior: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for applying variance partitioning to the study of individual behavior, a critical methodology for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational concepts of separating person, situation, and Person × Situation interaction effects, derived from Generalizability Theory and the Social Relations Model. The article delivers practical methodological guidance for implementing these analyses, addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies, and explores validation techniques and comparative frameworks. By synthesizing these four intents, this resource empowers scientists to robustly quantify the determinants of behavioral variation, thereby enhancing the precision and predictive power of biomedical and clinical research.

What is Variance Partitioning? Unpacking the P×S Interaction in Human Behavior

Variance partitioning is a statistical methodology used to quantify the contribution of different sources of variation to the total variability observed in a dataset. In scientific research, particularly in studies of individual behavior and drug development, understanding what drives variability is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions and developing targeted interventions. The core principle involves decomposing total variance into components attributable to specific factors, enabling researchers to determine which variables exert the most substantial influence on their outcomes of interest [1].

The fundamental equation underlying this approach can be expressed as: (yi = f(xi) + \epsiloni), where the response variable (yi) is shaped by both the deterministic influence of explanatory variables (f(xi)) and random influences (\epsiloni) representing unexplained variation or noise [1]. The goal of variance partitioning is to determine how much of (y) can be attributed to the deterministic influence (f(x)) and how much to the random influence (\epsilon) [1]. This approach has evolved significantly from its origins in classical ANOVA to sophisticated mixed-effects models that can handle the complex, multi-faceted datasets common in contemporary research.

Classical Foundations: ANOVA Framework

The fixed effects Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) model has served for decades as the foundational approach for decomposing variance into multiple components of variation [2]. In this classical framework, the total variance in a dataset is partitioned into systematic components attributable to different experimental factors and random error components. The method calculates the sum of squared errors for each model parameter, with the proportion of variance explained by each covariate calculated as the sum of squared errors associated with that covariate divided by the sum of squared errors of the null model [3].

A key output from this framework is the R-squared ((R^2)) statistic, calculated as the ratio of the variance of the model output to the total variance of the response variable [1]. This value, ranging from 0% to 100%, indicates what fraction of the total variance is accounted for by the explanatory variables in the model. For instance, in an analysis of Scottish hill racing data, the model time ~ distance + climb + sex achieved an R-squared value of 0.94, indicating that these three variables accounted for 94% of the variation in winning times [1]. Despite its utility, this classical ANOVA approach possesses significant limitations for complex modern datasets, particularly its inability to properly handle variables with large numbers of categories or its requirement for balanced designs [2].

Modern Approaches: Linear Mixed Models

The linear mixed model represents a substantial advancement over classical ANOVA for variance partitioning, offering greater flexibility and accuracy for complex experimental designs [2]. This framework employs a more sophisticated mathematical formulation:

[ y = \sum{j} X{j}\beta{j} + \sum{k} Z{k} \alpha{k} + \varepsilon ]

where (\alpha{k} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^{2}{\alpha{k}})) and (\varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^{2}{\varepsilon})) [2]. Here, (X{j}) represents the matrix of fixed effects with coefficients (\beta{j}), while (Z{k}) corresponds to random effects with coefficients (\alpha{k}) drawn from a normal distribution with variance (\sigma^{2}{\alpha{k}}) [2]. The total variance is calculated as:

[ \hat{\sigma}^{2}{Total} = \sum{j} \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\beta{j}} + \sum{k} \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\alpha{k}} + \hat{\sigma}^{2}{\varepsilon} ]

enabling the calculation of the fraction of variance explained by each component [2]. This approach provides three distinct advantages: it accommodates both fixed and random effects in a unified framework, properly handles variables with many categories through Gaussian priors, and produces more accurate variance estimates for complex experimental designs where standard ANOVA methods are inadequate [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Variance Partitioning Methods

| Feature | Classical ANOVA | Linear Mixed Models |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design Requirements | Balanced designs often required | Flexible for unbalanced designs |

| Variable Types | Primarily fixed effects | Both fixed and random effects |

| Statistical Basis | Sum of squares decomposition | Maximum likelihood or REML estimation |

| Implementation | Simplified calculations | Requires specialized software |

| Interpretation | R-squared values | Variance fractions and intra-class correlation |

Applications in Individual Behavior Research

Variance partitioning has proven particularly valuable in research on individual behavior, where understanding the sources of variability is essential for developing effective interventions. In behavior analysis, a core challenge involves addressing individual subject variability (also referred to as between-subject variance) that persists even in highly controlled experimental conditions [4]. Historically, researchers employed two primary approaches to manage this variability: the idiographic approach (e.g., single-subject designs) that focuses intensely on individuals, and the nomothetic approach that averages out individual differences through group-level analysis [4]. Both methods attempt to reduce the influence of individual-subject variability rather than understand its components.

Modern research recognizes that inter-individual variability affects various characteristics of animal disease models, including responsiveness to drugs [5]. For instance, in rodent models of temporal lobe epilepsy, individual animals display differential responses to antiseizure medications despite standardized breeding and experimental conditions, with approximately 20% consistently responding to phenytoin, 20% never responding, and 60% exhibiting variable responses [5]. This variability mirrors the clinical situation in human epilepsy patients and demonstrates the critical importance of partitioning variance to identify subpopulations with different treatment responses.

The variancePartition software package, specifically developed for interpreting drivers of variation in complex gene expression studies, provides a powerful tool for this type of analysis [2]. This R/Bioconductor package employs a linear mixed model framework to quantify variation in expression traits attributable to differences in disease status, sex, cell or tissue type, ancestry, genetic background, experimental stimulus, or technical variables [2]. The workflow involves fitting a linear mixed model for each gene to partition the total variance into components attributable to each aspect of the study design, plus residual variation.

Experimental Protocols for Variance Partitioning

Protocol 1: Partitioning Variance in Time Series Data

This protocol is adapted from methods used to analyze epidemiological data during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]:

- Data Preparation: Split time series data for key variables into relevant temporal periods (e.g., pre- and post-intervention).

- Model Specification: For each period, partition the variance of the response variable (e.g., effective reproduction number (R_e)) among explanatory variables (e.g., (\psi) for latent transmission trend and (\phi) for relative human mobility).

- Model Fitting: Fit two linear regressions using the

lm()function in R:- Intercept-only null model:

response ~ 1 - Full model with all covariates:

response ~ variable1 + variable2

- Intercept-only null model:

- Variance Calculation: Extract the sum of squared residuals for each model parameter using the

anova()function in R. - Variance Proportion Calculation: Compute the proportion of variance explained by each covariate as the sum of squared errors associated with each covariate divided by the sum of squared errors of the null model.

Protocol 2: Genome-Wide Variance Partitioning in Gene Expression Studies

This protocol utilizes the variancePartition package for transcriptome profiling data [2]:

- Data Preprocessing: Process gene expression data using standard normalization methods. Incorporate precision weights from limma/voom if appropriate.

- Model Specification: Define a linear mixed model formula that includes both fixed effects (e.g., disease status, sex) and random effects (e.g., individual, batch).

- Parallel Model Fitting: Use the variancePartition package to efficiently fit a linear mixed model for each gene in parallel on a multicore machine.

- Variance Extraction: For each gene, extract variance components using maximum likelihood estimation:

- Fixed effect variances: (\hat{\sigma}^{2}{\beta{j}} = var(X{j} \hat{\beta}{j}))

- Random effect variances: (\hat{\sigma}^{2}{\alpha{k}})

- Residual variance: (\hat{\sigma}^{2}_{\varepsilon})

- Variance Fraction Calculation: Compute the fraction of variance explained by each component as (\hat{\sigma}^{2}{\beta{j}} /\hat{\sigma}^{2}{Total}) for fixed effects and (\hat{\sigma}^{2}{\alpha{k}} /\hat{\sigma}^{2}{Total}) for random effects.

- Visualization and Interpretation: Use built-in ggplot2 visualizations to examine genome-wide patterns and identify genes that deviate from these trends.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Variance Partitioning Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| variancePartition R/Bioconductor Package | Statistical analysis and visualization of variance components | Genome-wide expression studies; quantifying biological and technical variation [2] |

| lme4 R Package | Core engine for fitting linear mixed-effects models | General variance partitioning applications; complex experimental designs [2] |

| ggplot2 R Package | Publication-quality visualization of variance components | Creating bar plots of variance fractions; visualizing genome-wide trends [2] |

| Amygdala Kindling Epilepsy Model | Animal model for studying inter-individual drug response | Investigating mechanisms of pharmacoresistance; identifying responder/non-responder subpopulations [5] |

| Concurrent Four-Choice Paradigm (Rodent) | Behavioral assay for studying individual differences in choice preference | Analyzing heterogeneity in decision-making; identifying subgroups with maladaptive choice patterns [4] |

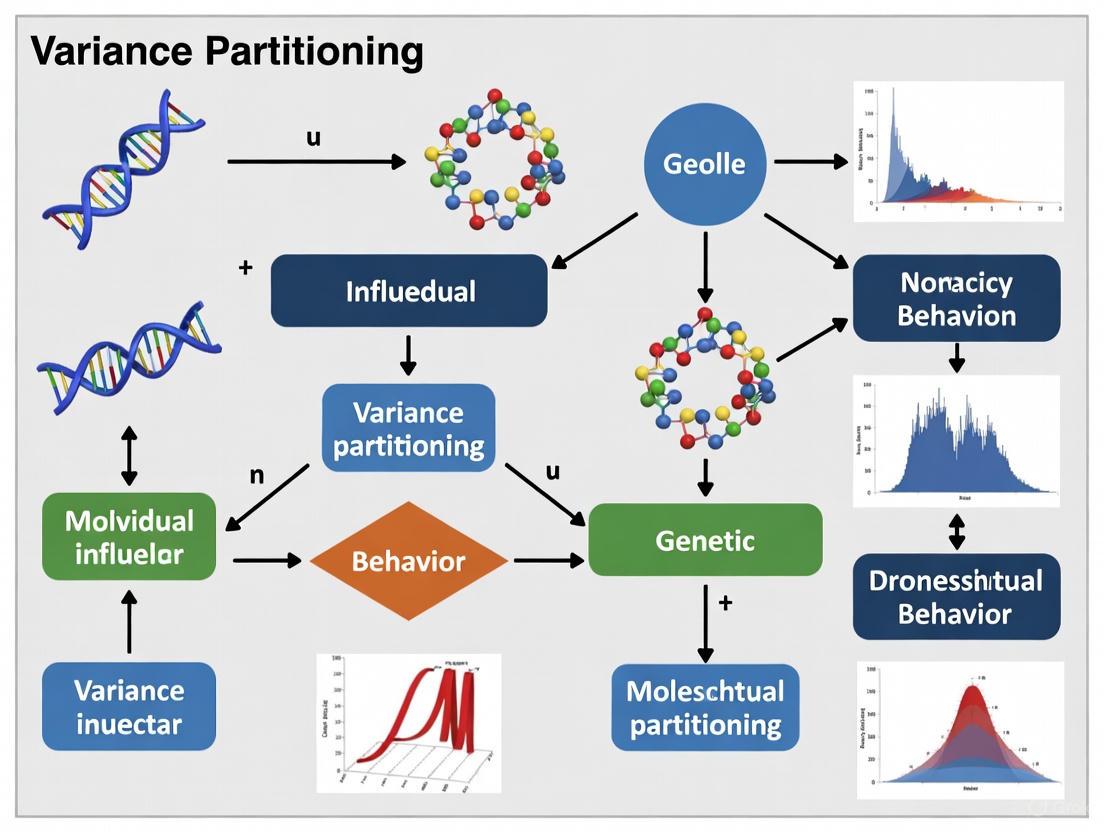

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Variance Partitioning Analysis Workflow

Variance Partitioning Analysis Workflow

Historical Development of Variance Partitioning Methods

Evolution of Variance Partitioning Methods

Implications for Drug Development

Variance partitioning has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development, particularly in understanding inter-individual variability in drug response [5]. Multiple factors contribute to this variability, including genetic variations affecting pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, age-related changes in organ function, gender differences, body weight and composition, disease states, drug interactions, and lifestyle factors [5]. The recognition that laboratory rodents also exhibit meaningful inter-individual variability in drug response—despite rigorous standardization in breeding and husbandry—has critical implications for preclinical research [5].

This approach enables the identification of subpopulations of responders and non-responders in both animal models and human populations, facilitating the development of stratified or personalized medicine approaches [5]. For instance, in epilepsy research, variance partitioning has revealed that kindled rats resistant to phenytoin were also resistant to several other antiseizure medications and differed in phenotypic and genetic aspects from responders [5]. This suggests the existence of stable traits underlying drug resistance rather than random variability, offering hope that animal models can be used to identify mechanisms of pharmacoresistance and develop more effective treatments.

The application of variance partitioning in drug development extends to optimizing pharmaceutical formulations. For example, studies partitioning the variance of drug compounds like naproxen in edible oil-water systems in the presence of ionic and non-ionic surfactants provide crucial information about lipophilicity and partitioning behavior that informs drug delivery system design [6]. By quantifying how different factors influence drug distribution, researchers can make more informed decisions about formulation strategies to enhance bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy.

Variance partitioning has evolved substantially from its origins in classical ANOVA to sophisticated mixed-model frameworks that can handle the complexity of modern biological and behavioral research. By enabling researchers to quantify the contribution of multiple sources of variation—including genetic, environmental, technical, and individual difference factors—these methods provide powerful insights into the drivers of variability in drug response and behavior. The continued development and application of variance partitioning approaches, particularly through tools like the variancePartition package and mixed-effects modeling frameworks, holds significant promise for advancing personalized medicine and improving the success rate of therapeutic interventions across diverse populations. As research continues to recognize the importance of individual differences, variance partitioning will remain an essential methodology for transforming heterogeneous data into meaningful biological insights.

Understanding the determinants of individual behavior requires a sophisticated approach that moves beyond simplistic main effects. The variance partitioning framework allows researchers to disentangle the complex interplay between an individual's inherent characteristics and the situations they encounter. This methodology quantifies the proportion of behavioral variance attributable to person effects (consistent individual differences), situation effects (influences common to a specific context), and Person × Situation (P×S) interactions (idiosyncratic responses of individuals to specific situations) [7]. This framework is fundamental for developing personalized interventions and treatments in clinical and pharmaceutical research, as it acknowledges that individuals show meaningful differences in their profiles of responses across the same situations [7] [8].

Core Conceptual Framework and Quantitative Evidence

Defining the Variance Components

In a typical repeated-measures design where multiple persons are exposed to multiple situations, any observed behavior (Xij) can be decomposed into its constituent parts. The foundational equation for this decomposition is derived from Generalizability Theory and can be represented as follows [7]:

Xij = M + Pi + Sj + PSij

Where:

- Xij is the score of person i in situation j

- M is the grand mean across all persons and situations

- Pi is the person effect (the extent to which person i differs from the grand mean averaged across situations)

- Sj is the situation effect (the extent to which situation j differs from the grand mean averaged across persons)

- PSij is the P×S interaction effect (the residual unique to person i in situation j after accounting for the main effects)

The P×S interaction is quantitatively defined as: PSij = Xij - Pi - Sj + M [7]. This represents behavior that cannot be explained by simply knowing a person's average tendencies or a situation's average effects, capturing instead how specific individuals respond uniquely to specific situations.

Empirical Evidence on Variance Components

Numerous studies across diverse psychological constructs have revealed substantial P×S effects. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from key research areas:

Table 1: Empirical Evidence of Variance Components Across Psychological Constructs

| Construct | Person Effects | Situation Effects | P×S Interaction Effects | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Significant individual differences in average anxiety levels | Situations vary in their anxiety-evoking potential | Very large P×S effects; individuals show unique anxiety profiles across situations | Endler & Hunt, 1966, 1969 [7] |

| Five-Factor Personality Traits | Evidence for cross-situational consistency | Situations influence trait expression | Large variability; from virtually zero for well-being to maximum for sociability across work/recreation | Van Heck et al., 1994; Diener & Larsen, 1984 [7] [8] |

| Perceived Social Support | Individuals differ in overall support perceptions | Support providers vary in general supportiveness | Very large effects; individuals receive support uniquely from specific providers | Lakey & Orehek, 2011 [7] |

| Leadership & Task Performance | Individual differences in average performance | Situational demands affect performance | Strong P×S effects; leadership effectiveness varies by context | Livi et al., 2008; Woods et al., in press [7] |

Table 2: Four Types of Person × Situation Interactions

| Interaction Type | Description | Level of Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| P × S | Broad Person × Situation interaction variance | Most general |

| P × Sspec | Between-person differences in associations between specific situation variables and outcomes | Intermediate |

| Pspec × S | Between-situation differences in associations between specific person variables and outcomes | Intermediate |

| Pspec × Sspec | Specific Person Variable × Situation Variable interactions | Most specific |

Recent research using this refined framework has found: (a) large overall P×S variance in personality states, (b) sizable individual differences in situation characteristic-state contingencies (P × Sspec), (c) consistent but smaller between-situation differences in trait-state associations (Pspec × S), and (d) some significant but very small specific Personality Trait × Situation Characteristic interactions (Pspec × Sspec) [9].

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Variance Components

Protocol 1: Basic Repeated-Measures Design for P×S Effects

This protocol outlines the fundamental methodology for partitioning variance in behavior.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Situation Stimuli | Presents identical situational contexts to all participants | 62 pictures or first-person perspective videos depicting various scenarios [9] |

| State-Based Measures | Assesses momentary behavioral, cognitive, or emotional states | Big Five personality states, anxiety measures, or task performance metrics [7] [9] |

| Trait Assessment Inventories | Measures stable person variables | Big Five personality traits, DIAMONDS situation characteristics [9] |

| Statistical Software for Multilevel Modeling | Analyzes nested data and partitions variance | R, SPSS, HLM, or Mplus for conducting variance decomposition |

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a representative sample of participants (N > 600 is recommended for adequate power) [9].

- Stimulus Presentation: Expose all participants to the same set of standardized situations. These can be presented in a fixed or randomized order to control for sequence effects.

- Response Measurement: After each situation, administer state measures relevant to the construct of interest (e.g., anxiety, personality states, perceived support).

- Data Structuring: Organize the data in a long format where each row represents a person-situation combination.

- Variance Decomposition: Conduct a random-effects Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or a multilevel model with persons and situations as random factors. The output will provide variance components for persons, situations, and their interaction.

- Effect Size Calculation: Compute the proportional variance for each component by dividing each variance component by the total variance.

Protocol 2: Social Relations Model (SRM) for Interpersonal Contexts

The SRM is a specialized variance partitioning approach for dyadic or group interactions where other people constitute the "situations."

Procedure:

- Round-Robin Design: In a group setting, have each participant interact with or rate every other participant in the group.

- Data Collection: Collect measures of the construct of interest (e.g., perceived support, leadership influence) for each dyadic interaction.

- SRM Analysis: Use specialized SRM software (e.g., SOREMO, TripleR) to partition the variance into:

- Perceiver Effect: Variance due to the person being rated (a situation effect).

- Relationship Effect: Variance unique to a specific perceiver-target dyad (a P×S interaction).

This method is particularly valuable for research on therapeutic alliances, team dynamics in clinical trials, and social support networks, as it quantifies the unique chemistry between specific individuals [7].

Advanced Analytical Considerations

Statistical Power and Effect Sizes

A critical consideration in variance partitioning research is ensuring adequate statistical power. Low power inflates Type II error rates (the failure to detect a true effect), jeopardizing the reproducibility of findings [10]. The power of a statistical test is a function of the effect size, sample size, and Type I error rate (alpha, typically set at 0.05) [10]. For P×S studies, this often requires large samples of both persons and situations. Researchers should conduct power analyses a priori. Furthermore, while variance components provide estimates of effect magnitude, it is crucial to also consider clinically meaningful effects, which reflect whether a treatment effect is practically significant from the perspectives of patients, clinicians, and payers, rather than merely statistically significant [11].

Challenges and Limitations

The variance partitioning approach faces several conceptual and analytical challenges:

- Situation Sampling: Obtaining a representative sample of situations for a given behavior remains an unresolved methodological issue, and the heterogeneity of the situation sample directly influences the estimated size of P×S interactions [8].

- Design Impact: The choice between ecological (e.g., experience sampling) and experimental designs affects results. P×S interactions tend to be smaller in ecological designs where people select their own situations [8].

- Interpretation Complexity: While P×S effects can be large, explaining these effects through specific psychological mechanisms (specific person variables and situation variables) has proven difficult [9].

- Suppression Effects: In statistical modeling, the intuitive Venn-diagram view of variance partitioning can be misleading. Suppression effects can occur, leading to situations where the combined variance explained by two predictors is greater than the sum of their individual contributions, resulting in negative "shared variance" estimates [12]. This underscores that a variable's contribution must always be interpreted within the context of the other variables in the model.

Generalizability (G) Theory and the Social Relations Model (SRM) represent complementary statistical frameworks for partitioning variance in behavioral measurements. Both approaches move beyond classical test theory by simultaneously examining multiple sources of error variance, providing researchers with sophisticated tools for understanding the dependability of measurements and the origins of behavioral variation [13] [14]. These methods are particularly valuable for investigating the Person × Situation (P×S) aspect of within-person variation, which represents differences among persons in their profiles of responses across the same situations [15] [7]. This P×S interaction captures the idiosyncratic ways individuals respond to specific situations, beyond their general trait-like tendencies and beyond the situation's normative effect on all people [7].

G Theory liberalizes classical test theory by employing analysis of variance methods that disentangle the multiple sources of error that contribute to the undifferentiated error in classical theory [13]. Similarly, the SRM applies variance partitioning to dyadic data where other people serve as the "situations" in round-robin designs [7]. Together, these approaches have revealed substantial P×S effects across diverse psychological constructs including anxiety, five-factor personality traits, perceived social support, leadership, and task performance [15] [7].

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

Core Concepts of Generalizability Theory

G Theory introduces several key concepts that differentiate it from classical test theory. Among these are universes of admissible observations and G studies, as well as universes of generalization and D studies [13]. The universe of admissible observations encompasses all possible conditions for a measurement (e.g., different raters, occasions, items), while G studies estimate variance components associated with these facets [13]. D studies then use these variance components to design efficient measurement procedures for decision-making [16].

In G Theory, any single measurement from an individual is viewed as a sample from a universe of possible measurements [16]. The framework distinguishes between facets of measurement (sources of variance such as raters, items, or occasions) and conditions (the specific instances of each facet) [16]. Facets can be characterized as random (interchangeable, randomly selected) or fixed (stable across measurements) [16].

The mathematical foundation of G Theory begins with a decomposition of an observed score:

$$X{pi} = \mu + \nup + \nui + \nu{pi}$$

Where $X{pi}$ is the observed score for person $p$ under condition $i$, $\mu$ is the grand mean, $\nup$ is the person effect, $\nui$ is the condition effect, and $\nu{pi}$ is the residual person × condition effect [13]. This model expands to accommodate multiple facets, with variance components estimated for each facet and their interactions.

Core Concepts of the Social Relations Model

The Social Relations Model applies variance partitioning to dyadic data where people interact with or rate one another in round-robin designs [7]. The SRM defines P×S effects in the same way as G Theory but applies to the special case where other people are the situations [7]. This represents an important conceptual advance because it acknowledges that important determinants of situational effects are the specific people who populate the situation [7].

The basic SRM equation for a dyadic response is:

$$X{ijk} = \mu + \alphai + \betaj + \gamma{ij} + \epsilon_{ijk}$$

Where $X{ijk}$ is the response of person $i$ to person $j$ in group $k$, $\mu$ is the grand mean, $\alphai$ is the actor effect (person i's general tendency across partners), $\betaj$ is the partner effect (person j's tendency to elicit responses across actors), $\gamma{ij}$ is the relationship effect (the unique adjustment between i and j), and $\epsilon_{ijk}$ is measurement error [7].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship and components of both models:

Quantifying P×S Effects

In both frameworks, P×S effects are defined quantitatively. For a simple design where persons are exposed to the same situations, the P×S effect is calculated as:

$$P×S = X{ij} - Pi - S_j + M$$

Where $X{ij}$ is person i's score in response to situation j, $Pi$ is the person's mean score across all situations (person effect), $S_j$ is the situation's mean score across all persons (situation effect), and $M$ is the grand mean [7]. This effect represents the unique response of a specific person to a specific situation, beyond their general tendencies and beyond the situation's normative effect.

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Basic G Study for Performance Assessment

Objective: To estimate variance components for an OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) measuring resuscitation skills [16].

Design Features:

- Fully crossed design: persons × stations × raters

- 6 stations, 2 raters per station, 50 participants

- Each participant completes all stations and is rated by all assigned raters

Procedures:

- Study Setup: Identify all likely sources of variance (facets) including persons, stations, raters, and potential fixed facets such as trainee gender [16].

- Data Collection: Organize data collection according to a fully crossed design where possible [16].

- Variance Component Estimation: Conduct G-study using appropriate statistical software to estimate variance components for all main effects and interactions.

- G-Coefficient Calculation: Compute generalizability coefficients for relative and absolute decisions [16].

Analysis Notes:

- Determine the proportion of variance attributable to each facet and their interactions

- Calculate relative G-coefficient for norm-referenced decisions: $EÏ^2 = σ^2(p) / [σ^2(p) + σ^2(δ)]$

- Calculate absolute G-coefficient for criterion-referenced decisions: $Φ = σ^2(p) / [σ^2(p) + σ^2(Δ)]$

- Use D-studies to optimize future measurement designs by varying numbers of stations or raters [16]

Protocol 2: SRM Round-Robin Design for Social Support

Objective: To partition variance in perceived social support into actor, partner, and relationship effects [7].

Design Features:

- Round-robin design with 5-8 person groups

- Each participant rates every other participant on social support provision

- Multiple measurements occasions (optional)

Procedures:

- Group Formation: Create natural or artificial groups of 5-8 participants to allow for complete round-robin data collection [7].

- Measurement: Administer social support measures where each participant rates every other group member on relevant dimensions.

- Data Structure: Organize data according to dyadic relationships with actor and partner identified for each observation.

- SRM Analysis: Use specialized SRM software to estimate actor, partner, and relationship variance components.

Analysis Notes:

- Actor variance indicates individual differences in general perception of support from others

- Partner variance indicates individual differences in general tendency to be seen as supportive

- Relationship variance indicates unique dyadic perceptions beyond actor and partner effects

- P×S effects in this context represent the relationship effects [7]

Protocol 3: Longitudinal P×S Study for Personality Expression

Objective: To examine within-person variation in five-factor personality traits across different situations [7].

Design Features:

- Repeated measures design with multiple situations

- 100 participants, 10 situations per participant, 3 time points

- Situation characteristics systematically coded

Procedures:

- Situation Sampling: Select a representative range of situations that participants regularly encounter.

- Repeated Measures: Administer brief personality measures following each situation exposure.

- Situation Coding: Code situations on relevant dimensions (e.g., sociality, conflict, achievement)

- Data Analysis: Use multilevel modeling or random effects ANOVA to partition variance.

Analysis Notes:

- Estimate proportion of variance due to persons, situations, and P×S interactions

- Test situation characteristics as moderators of personality expression

- Examine consistency of P×S profiles across time

- Potential to identify situational signatures for individuals [7]

Quantitative Evidence and Variance Component Tables

Empirical Evidence for P×S Effects

Research using variance partitioning approaches has demonstrated substantial P×S effects across diverse psychological domains:

Table 1: Magnitude of P×S Effects Across Psychological Constructs

| Construct | Domain | P×S Effect Size | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Clinical | Large | Endler & Hunt (1966, 1969) [7] |

| Five-Factor Traits | Personality | Large | Van Heck et al. (1994); Hendriks (1996) [7] |

| Social Support | Social | Very Large | Lakey & Orehek (2011) [15] [7] |

| Leadership | Organizational | Large | Livi et al. (2008); Kenny & Livi (2009) [7] |

| Task Performance | I-O Psychology | Large | Woods et al. (in press) [7] |

| Family Negativity | Clinical | Large | Rasbash et al. (2011) [7] |

| Attachment | Developmental | Large | Cook (2000) [7] |

Example Variance Partitioning from Assessment Studies

Table 2: Variance Components for Listening and Writing Assessment (n=50)

| Variance Component | Listening | Writing | Covariance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Person | 0.324 | 0.691 | 0.356 |

| Task | 0.116 | 0.147 | 0.092 |

| Rater | 0.021 | 0.008 | - |

| Person × Task | 0.228 | 0.314 | 0.028 |

| Person × Rater | 0.017 | 0.012 | - |

| Residual | 0.121 | 0.105 | - |

Note: Adapted from Brennan et al. (1995) as cited in [13]. Disattenuated correlation between Listening and Writing universe scores: Ï = .75.

Optimizing Measurement Designs Using D-Studies

Table 3: Generalizability Coefficients for Various Assessment Designs

| Design | Number of Stations | Number of Raters | Relative G-Coefficient | Absolute G-Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSCE | 6 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| OSCE | 8 | 1 | 0.73 | 0.70 |

| OSCE | 10 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.74 |

| OSCE | 6 | 2 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| OSCE | 8 | 2 | 0.74 | 0.71 |

Note: Adapted from medical education example [16]. Increasing stations has greater impact on reliability than increasing raters.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process of conducting generalizability studies and decision studies:

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Tools

Essential Analytical Tools for Variance Partitioning Research

Table 4: Key Methodological Resources for G-Theory and SRM Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | urGENOVA, mGENOVA, EDUG | Estimates variance components for unbalanced designs | Specialized G-theory programs [17] |

| Statistical Software | SAS VARCOMP, SPSS VARCOMP, R lme4 | General variance component estimation | Flexible but requires careful specification [17] |

| SRM Software | SOREMO, TripleR, WinSoReMo | Social Relations Model analysis | Handles round-robin dyadic data [7] |

| Design Planning | D-study simulations | Optimizes measurement designs for target reliability | Uses variance components from G-studies [16] |

| Data Collection | Experience sampling methods | Captures within-person variation across situations | Mobile technologies facilitate intensive sampling [7] |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Methods

The integration of G Theory with structural equation modeling represents a promising advancement that combines the variance partitioning focus of G Theory with the latent variable modeling capabilities of SEM [17]. This integration allows researchers to model measurement error while simultaneously testing complex structural hypotheses about relationships among constructs.

Similarly, multivariate generalizability theory extends the basic framework to multiple dependent variables simultaneously [13]. This approach allows researchers to estimate covariance components between different measures and to examine the generalizability of composite scores [13]. For example, in an assessment of both listening and writing skills, multivariate G Theory can estimate the correlation between universe scores on the two domains while accounting for measurement error [13].

These advanced applications demonstrate how variance partitioning approaches continue to evolve, offering researchers increasingly sophisticated tools for understanding the complex origins of behavioral variation and the precision of their measurements.

Application Notes

This document provides Application Notes and Protocols for investigating Person × Situation (P×S) effects, focusing on the interplay between social support (a key personal resource), anxiety, and external stressors. The framework is essential for variance partitioning in individual behavior research, distinguishing the unique effects of personal characteristics, situational factors, and their critical interactions. Understanding these interactions is paramount for developing targeted interventions and therapeutics in mental health and drug development.

Recent empirical studies underscore that the effect of situational stressors (e.g., a global pandemic) on anxiety is not uniform but is significantly moderated by personal and social resources. The following summaries present quantitative evidence of these complex relationships, highlighting the necessity of a P×S lens.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings on Social Support and Anxiety

| Study Population & Design | Key Independent Variable(s) | Key Outcome Variable | Major Quantitative Findings | Statistical Methods Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,097 college students (Hunan Province); Cross-sectional survey [18] | Social Support (SS), Resilience (R), Physical Exercise (PE) | Anxiety (GAD-7 score) | - SS negatively predicts anxiety (β = -0.28, p < .001).- Family support was the most potent dimension.- R mediated the SS-Anxiety relationship (Indirect effect = -0.15, 95% CI [-0.19, -0.11]).- PE moderated the SS-Anxiety pathway. | Correlation analysis, Mediation analysis (PROCESS Model 4), Moderation analysis (PROCESS Model 5) |

| 3,165 college students (Shaanxi Province); Cross-sectional survey during COVID-19 lockdown [19] | Perceived COVID-19 Risk (PCR), Social Support (SS), Gender | Anxiety | - PCR significantly positively predicted anxiety (β = 0.34, p < .001).- SS moderated the PCR-Anxiety relationship (Interaction β = -0.11, p < .01).- Gender showed multiple interaction effects with SS and PCR on anxiety levels. | Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), Moderation analysis (SPSS PROCESS 4.0) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Investigating the Mediating and Moderating Mechanisms in the Social Support-Anxiety Pathway

This protocol is adapted from the study on social support, resilience, and physical exercise [18].

I. Research Objective To examine the relationship between social support and anxiety among college students, specifically testing the mediating role of resilience and the moderating effect of physical exercise.

II. Participants & Sampling

- Population: College students.

- Sample Size: Target approximately 1,000 participants to ensure sufficient power for mediation/moderation analysis.

- Sampling Method: Convenience sampling from multiple universities to enhance diversity.

- Ethical Considerations: Obtain informed consent online. Ensure data anonymity and confidentiality. Inform participants of their right to withdraw. The study should adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki.

III. Materials and Measures

- Perceived Social Support: Use the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS). A 12-item scale measuring family, friend, and significant other support on a 7-point Likert scale. The total score is the sum of all items [18].

- Resilience: Use the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). A 25-item scale measuring tenacity, strength, and optimism on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4). The total score is the sum of all items [18].

- Physical Exercise: Use the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). A 27-item questionnaire categorizing participants' activity levels as low, moderate, or high based on metabolic equivalent tasks (METs) [18].

- Anxiety: Use the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale. Scores range from 0-21, with categories for minimal (0-4), mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), and severe (15-21) anxiety [18].

IV. Procedure

- Administration: Distribute the electronic questionnaire battery (PSSS, CD-RISC, IPAQ, GAD-7) via online platforms to participants.

- Completion Time: Allocate approximately 15 minutes for completion.

- Data Screening: Exclude responses with completion times that are too short (e.g., <10 minutes) or with obvious patterned responses (e.g., straight-lining) to ensure data quality.

V. Quantitative Data Analysis

- Preliminary Analysis:

- Conduct descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) for all variables.

- Perform Pearson correlation analyses to examine zero-order relationships between social support, resilience, physical exercise, and anxiety.

- Check for common method bias using Harman's single-factor test.

- Mediation and Moderation Analysis:

- Use a statistical macro like PROCESS for SPSS/SPSS (e.g., Models 4 and 5).

- Model 4: Test the mediating effect of resilience in the relationship between social support and anxiety.

- Model 5: Test the moderating effect of physical exercise on the direct path between social support and anxiety (or on the mediation model).

- Use bootstrapping (e.g., 5,000 samples) to generate confidence intervals for indirect effects. An effect is significant if the 95% CI does not contain zero.

Protocol: Examining the Moderating Role of Social Support and Gender in a Stressful Situation

This protocol is adapted from the COVID-19 risk perception study [19].

I. Research Objective To investigate how perceived risk from a major situational stressor (COVID-19) predicts anxiety, and to determine whether this relationship is moderated by social support and participant gender.

II. Participants & Sampling

- Population: College students undergoing a specific, significant stressor (e.g., pandemic lockdown, academic exams).

- Sample Size: Target a large sample (N > 3,000) to detect interaction effects, which often require greater power.

- Sampling Method: Purposive sampling of cohorts experiencing the situational stressor. Stratified sampling by year and major can improve representativeness.

III. Materials and Measures

- Perceived Situation-Specific Risk: Develop or adapt a scale to measure the perceived threat and stress associated with the situational stressor (e.g., "Perceived COVID-19 Risk" scale).

- Social Support: Use a validated scale like the PSSS (as in Protocol 2.1).

- Anxiety: Use the GAD-7 scale (as in Protocol 2.1).

- Demographics: Collect data on gender, age, and other relevant demographic variables.

IV. Procedure

- Timing: Administer the survey during the period of the situational stressor.

- Administration: Use a professional online survey platform. Collect data efficiently across multiple sites if necessary.

- Data Cleaning: Exclude responses with missing answers and repetitive patterns to ensure a clean dataset for analysis.

V. Quantitative Data Analysis

- Preliminary Analysis: Conduct descriptive statistics and correlation analyses.

- Moderation Analysis:

- Use PROCESS Macro (e.g., Model 1) or similar to test the two-way interaction between perceived risk and social support on anxiety.

- To test for three-way interactions (e.g., Risk × Social Support × Gender), use Model 3.

- Probing Interactions: If a significant interaction is found, conduct simple slopes analysis to test the effect of the independent variable (perceived risk) on the dependent variable (anxiety) at different levels of the moderator (e.g., high and low social support).

- The analysis can be extended using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with AMOS or similar software to model complex relationships with latent variables.

Mandatory Visualization

Conceptual Diagram of P×S Effects in Anxiety Research

Experimental Workflow for Quantitative Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Social Support and Anxiety Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) | Psychometric Scale | Quantifies an individual's perception of support from family, friends, and significant others. It is the standard tool for measuring the "Personal Resource" variable [18]. |

| GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item) | Clinical Assessment | Provides a reliable and valid measure of anxiety symptom severity. Serves as a key outcome variable ("Clinical Outcome") in studies [18] [19]. |

| Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Psychometric Scale | Measures the psychological construct of resilience, often tested as a "Mediator" between protective factors and mental health outcomes [18]. |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) | Behavioral Assessment | Categorizes participants' physical activity levels, used to investigate "Moderator" variables in the relationship between psychology and health [18]. |

| SPSS PROCESS Macro | Statistical Software Tool | A computational tool for path analysis-based mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Essential for testing complex P×S interaction hypotheses [18] [19]. |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Software (e.g., AMOS) | Statistical Software Tool | Allows researchers to model complex relationships involving latent variables and multiple pathways, facilitating robust variance partitioning [19]. |

| Gomisin K1 | Gomisin K1, CAS:75684-44-5, MF:C23H30O6, MW:402.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Salipurpin | Salipurpin, MF:C21H20O10, MW:432.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Understanding the sources of variation in behavioral data is fundamental to individual behavior research. This framework partitions observed behavior into consistent individual differences (person effects), situational influences (situation effects), and the unique ways individuals respond to specific contexts (Person × Situation interactions) [20]. Quantitative variance partitioning allows researchers to move beyond simplistic trait-based explanations and develop more nuanced models of behavior that acknowledge both consistency and context-dependency. These methods are particularly valuable in drug development where understanding individual response variability to interventions is critical.

Core Statistical Metrics: R-squared and Adjusted R-squared

Interpreting R-squared in Behavioral Contexts

R-squared (R²) represents the percentage of variance in the dependent variable that the independent variables explain collectively [21]. In behavioral research, this indicates how much of the behavioral outcome is accounted for by your model. Unlike physical processes, human behavior typically involves greater unexplainable variation, resulting in R² values that are often lower than in other fields [21].

Key limitations of R-squared include its inability to indicate whether coefficient estimates and predictions are biased, and its tendency to increase with additional predictors regardless of their true relevance [21]. A model with a high R² value may still be biased and provide poor predictions if residual patterns are non-random [21].

Adjusted R-squared for Model Comparison

Adjusted R-squared (R²â‚) addresses the positive bias of standard R² by introducing a penalty for additional predictors [22]. It is calculated as:

R²₠= 1 - (1 - R²)(n - 1)/(n - s - 1)

where n represents sample size and s represents the number of explanatory variables [22]. This adjustment makes it particularly valuable for comparing nested models (where one model contains a subset of another model's predictors) in behavioral research [22].

Table 1: Comparison of R-squared Metrics

| Metric | Interpretation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-squared | Percentage of variance explained by the model | Intuitive 0-100% scale | Optimistic estimate of population fit; increases with added predictors |

| Adjusted R-squared | Variance explained adjusted for number of predictors | Less biased; suitable for model comparison | Less intuitive interpretation; requires larger samples |

Variance Components in Behavioral Data

Person, Situation, and Person × Situation Effects

Variance partitioning in behavioral research typically identifies three core components:

- Person effects: Represent trait-like, cross-situational consistency in behavior [20]. These reflect how much individuals differ from the grand mean in their levels of a behavior, averaged across situations.

- Situation effects: Capture the extent to which situations differ in evoking behaviors across persons [20]. These represent normative influences on behavior.

- Person × Situation (P×S) interactions: Reflect idiosyncratic patterns where individuals show different behavioral profiles across the same situations [20]. These are quantitatively defined as: P×S = Xij - Pi - Sj + M, where xij is person i's score in situation j, Pi is the person's mean across situations, Sj is the situation's mean across persons, and M is the grand mean [20].

Empirical Evidence for Variance Components

Research across diverse behavioral domains demonstrates substantial P×S effects. In anxiety studies across 22 samples, P×S interactions accounted for 17% of variance, compared to 8% for person effects and 7% for situation effects [20]. Similar substantial P×S effects have been documented for five-factor personality traits, perceived social support, leadership, and task performance [20].

Table 2: Variance Components Across Behavioral Domains

| Behavioral Domain | Person Effects | Situation Effects | P×S Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 8% | 7% | 17% |

| Social Support | Varies | Varies | Strong effects |

| Leadership | Varies | Varies | Strong effects |

| Task Performance | Varies | Varies | Strong effects |

Experimental Protocols for Variance Partitioning

Research Design Specifications

The fundamental design for partitioning behavioral variance requires multiple persons measured across multiple situations. The minimal recommended design involves at least 30-50 participants measured across 5-10 systematically varied situations to reliably estimate variance components. Situations should be selected to represent ecologically valid contexts relevant to the behavioral construct under investigation.

Data Collection Workflow

Statistical Analysis Protocol

- Data Preparation: Structure data in long format with one row per person-situation combination

- Variance Component Estimation: Use Generalizability Theory or Social Relations Model frameworks to partition variance [20]

- Model Fitting: Implement linear mixed models with random effects for persons, situations, and their interaction

- R-squared Calculation: Compute both standard and adjusted R² for model comparison [22]

- Significance Testing: Use appropriate methods (e.g., likelihood ratio tests) for nested model comparisons

Analytical Framework for Behavioral Variance

Research Reagent Solutions for Behavioral Studies

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Behavioral Variance Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Repeated Measures Design | Enables separation of person, situation, and interaction effects | Within-subjects exposure to multiple standardized situations |

| Generalizability Theory | Statistical framework for variance partitioning | Estimating magnitude of P×S interactions across multiple samples [20] |

| Social Relations Model | Specialized approach for social situations | Round-robin designs where people interact with multiple others [20] |

| Multilevel Modeling | Accounts for nested data structure | Mixed-effects models with random intercepts and slopes |

| Standardized Behavioral Measures | Ensures metric consistency across situations | Validated scales with demonstrated cross-situational reliability |

Application in Drug Development Research

In pharmaceutical contexts, variance partitioning helps distinguish consistent drug effects (person/situation components) from idiosyncratic responses (P×S components). This framework enables researchers to:

- Identify patient subgroups with distinctive response patterns

- Optimize dosing regimens for different contexts

- Predict real-world effectiveness beyond controlled trials

- Design targeted interventions for specific person-situation combinations

The substantial P×S effects documented across behavioral domains highlight the importance of considering individual response patterns rather than assuming uniform treatment effects across all individuals in all contexts [20].

Interpreting R-squared and variance components provides a sophisticated analytical approach for understanding the complex determinants of behavior. By simultaneously considering explanatory power (R² and adjusted R²) and variance components (person, situation, and P×S effects), researchers can develop more nuanced models that acknowledge both consistency and context-dependency in behavior. These methods are particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to understand and predict individual differences in treatment response.

How to Implement Variance Partitioning: Study Designs and Analytical Workflows

In the study of individual behavior, a fundamental challenge lies in disentangling the complex sources of behavioral variation. Research designs that can systematically partition variance into its constituent components are therefore essential for advancing our understanding of behavioral dynamics. Repeated-measures and round-robin configurations represent two powerful methodological approaches that enable researchers to quantify different sources of behavioral influence. These designs move beyond merely describing population-level patterns to revealing the intricate architecture of individual differences, situational influences, and their interactions.

The theoretical foundation of these approaches rests upon the principle that observable behavior emerges from multiple latent sources of variance. In repeated-measures designs, the total variance is partitioned into between-subjects and within-subjects components, allowing researchers to distinguish stable individual differences from temporal fluctuations or treatment-induced changes [23]. Round-robin designs, often analyzed through the Social Relations Model (SRM), extend this logic to social interactions by further decomposing variance into actor, partner, and relationship effects [20] [24]. This variance partitioning provides critical insights for diverse fields including clinical psychology, pharmaceutical development, and behavioral ecology, where understanding the sources of behavioral variation directly impacts intervention strategies and treatment efficacy.

Theoretical Foundations and Variance Components

Repeated-Measures Design: Partitioning Within and Between-Subject Variance

In repeated-measures designs, the same experimental units (e.g., participants, patients, animals) are observed under multiple conditions or time points [23] [25]. This fundamental structure enables the partitioning of total variance into two primary components: between-subjects variance and within-subjects variance. The between-subjects variance (SSsubjects) reflects individual differences in average response levels across all measurements, representing stable traits or predispositions. The within-subjects variance is further divided into systematic treatment effects (SSbetween) attributable to the experimental conditions or time points, and residual error (SS_residual) representing unexplained variability [23].

The statistical model for a simple repeated-measures design can be represented as:

Yij = μ + πi + τj + εij

Where Yij is the response for subject i in condition j, μ is the grand mean, πi is the subject effect (individual difference), τj is the treatment effect, and εij is the residual error [23]. The F-ratio of primary interest is typically s²bet/s²resid, which tests whether the treatment effects are statistically significant beyond individual differences and random error [23].

Table 1: Variance Components in Repeated-Measures Designs

| Variance Component | Symbol | Interpretation | Research Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between-Subjects | SS_subjects | Stable individual differences across conditions | Usually not primary focus |

| Treatment Effects | SS_bet | Systematic differences between conditions/time | Primary interest for hypothesis testing |

| Residual Error | SS_resid | Unexplained within-subject variability | Measurement error, individual treatment responses |

Round-Robin Design: The Social Relations Model

Round-robin designs extend the logic of variance partitioning to interpersonal phenomena using the Social Relations Model (SRM) [20] [24]. In these designs, each member of a group interacts with or assesses every other member, creating a complete matrix of interactions. The SRM decomposes behavioral variance in social interactions into three primary components: actor effects (consistent behaviors an individual displays toward others), partner effects (consistent responses an individual elicits from others), and relationship effects (unique interactions between specific dyads that cannot be explained by actor or partner effects alone) [24].

The SRM conceptualizes Person × Situation (P×S) interactions as differences among persons in their profiles of reactions to the same situations, beyond the person's trait-like tendency to respond consistently and the situation's tendency to evoke consistent responses [20]. The model quantifies these P×S effects using the formula: P×S = Xij - Pi - Sj + M, where Xij is person i's score in response to situation j, Pi is the person's mean score across situations, Sj is the situation's mean score across persons, and M is the grand mean [20].

Table 2: Variance Components in Round-Robin Designs (Social Relations Model)

| Variance Component | Interpretation | Research Example |

|---|---|---|

| Actor Effects | Consistent behaviors an individual displays toward different partners | A child's general tendency to express anger toward all peers |

| Partner Effects | Consistent responses an individual elicits from different partners | A child's general tendency to elicit anger from all peers |

| Relationship Effects | Unique interactions between specific dyads | Particular anger expression between two specific children beyond their general tendencies |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Repeated-Measures Clinical Trial Design

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a novel pharmaceutical intervention (Dhatrilauha) for Iron Deficiency Anemia across multiple time points [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Investigational product: Dhatrilauha formulation

- Placebo control: Identical in appearance to investigational product

- Hemoglobin measurement apparatus: Standardized laboratory equipment

- Data collection forms: Electronic Case Report Forms (eCRF)

Participant Selection:

- Inclusion criteria: Adults aged 18-65 with confirmed iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin <12 g/dL for women, <13 g/dL for men)

- Exclusion criteria: Concurrent hematological disorders, recent blood transfusions, pregnancy

- Sample size: 423 patients (as per original study) provides adequate power for detecting clinically meaningful changes [25]

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment (Day 0): Obtain informed consent, administer demographic questionnaire, collect initial hemoglobin measurement

- Randomization: Assign participants to treatment sequence using computer-generated randomization schedule

- Treatment Administration: Dispense first intervention period medication with detailed administration instructions

- Follow-up Assessments: Conduct identical hemoglobin measurements at Day 15, Day 30, and Day 45 post-intervention

- Compliance Monitoring: Implement pill counts and patient diaries to track medication adherence

- Data Collection: Record all measurements using standardized procedures to minimize measurement error

Statistical Analysis Plan:

- Data Screening: Examine distributions for normality, identify outliers, assess missing data patterns

- Sphericity Testing: Conduct Mauchly's test to evaluate sphericity assumption [25]

- Primary Analysis: One-way repeated-measures ANOVA comparing hemoglobin levels across four time points

- Assumption Violations: Apply Greenhouse-Geisser correction if sphericity is violated [25] [26]

- Post Hoc Testing: Conduct pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction to identify specific time points showing significant change

Diagram 1: Repeated-Measures Clinical Trial Workflow

Protocol 2: Round-Robin Assessment of Children's Emotion Expression

Objective: To investigate trait-like versus dyadic influences on children's emotion expression during peer interactions [24].

Materials:

- Laboratory space configured for dyadic interactions

- Video recording equipment: Multiple cameras for comprehensive angle coverage

- Behavioral coding software: The Observer XT or equivalent

- Age-appropriate tasks: Cooperative planning and challenging frustration tasks

- Emotion coding scheme: Operational definitions for happy, sad, angry, anxious, and neutral expressions

Participant Selection:

- Inclusion criteria: Typically developing children aged 9 years, same-sex groupings

- Exclusion criteria: Developmental disorders that would impede task comprehension

- Group composition: 202 children arranged in 23 groups of 4 participants each [24]

Procedure:

- Group Formation: Arrange participants into same-sex groups of four unfamiliar peers

- Task Administration:

- Cooperative Planning Task: Dyads work together to plan a party with limited resources

- Challenging Frustration Task: Dyads complete difficult puzzle with time constraints

- Round-Robin Implementation: Each participant interacts with every other group member in both tasks (6 dyads per group)

- Behavioral Recording: Film interactions using multiple camera angles for comprehensive behavioral sampling

- Behavioral Coding: Trained observers code children's emotions on a second-by-second basis using standardized coding scheme

Behavioral Coding Protocol:

- Coder Training: Train observers to 85% inter-rater reliability criterion

- Blinding: Keep coders unaware of study hypotheses and participant characteristics

- Continuous Coding: Apply emotion codes continuously throughout 5-minute interaction periods

- Reliability Checks: Conduct periodic inter-rater reliability assessments on 20% of recordings

Statistical Analysis Plan:

- Data Preparation: Aggregate emotion frequencies by dyad and task

- SRM Analysis: Use specialized SRM software (SOREMO or R package) to partition variance into actor, partner, and relationship components [24]

- Variance Component Estimation: Calculate proportion of total variance attributable to each source

- Correlational Analysis: Examine multivariate relationships between different emotion expressions

Diagram 2: Round-Robin Emotion Expression Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Repeated-Measures and Round-Robin Studies

| Research Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biologging Devices | Continuous automated tracking of individual behavior and movement | Studying animal personality in movement ecology [27] |

| Video Recording Equipment | Comprehensive capture of behavioral interactions for later coding | Observing children's emotion expression in dyadic tasks [24] |

| Behavioral Coding Software | Systematic quantification of observed behaviors using standardized schemes | Coding emotion expression on second-by-second basis [24] |

| Standardized Assessment Kits | Consistent measurement of clinical outcomes across multiple time points | Hemoglobin measurement in anemia clinical trials [25] |

| SRM Analysis Software | Variance partitioning of round-robin data into actor, partner, relationship effects | SOREMO, R packages, or specialized SRM programs [20] [24] |

| Experimental Task Protocols | Standardized procedures for eliciting target behaviors across participants | Cooperative planning and frustration tasks for emotion elicitation [24] |

| Bakkenolide III | Bakkenolide III, MF:C15H22O4, MW:266.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Karavilagenin B | Karavilagenin B, MF:C31H52O3, MW:472.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Analytical Approaches for Repeated Measures

The analysis of repeated-measures data requires specialized techniques that account for the non-independence of observations within subjects [26]. Three primary classes of analytical approaches are commonly employed:

Summary Statistic Approach: This method condenses each participant's repeated measurements into a single meaningful value (e.g., mean, slope, area under the curve), which can then be analyzed using standard between-subjects tests [26]. While simple and intuitive, this approach sacrifices information about within-subject change patterns.

Repeated-Measures ANOVA: This traditional approach tests hypotheses about mean differences across time points or conditions while modeling within-subject correlations [25] [26]. The approach requires meeting the sphericity assumption (equal variances of differences between all pairs of repeated measures), which is often violated in practice [25]. Corrections such as Greenhouse-Geisser or Huynh-Feldt adjustments mitigate the increased Type I error risk when sphericity is violated [25].

Mixed-Effects Models: These modern, flexible approaches (also known as multilevel or hierarchical models) accommodate various correlation structures and can handle missing data and time-varying covariates [26]. Mixed-effects models can be further divided into population-average models (focusing on marginal means estimated via Generalized Estimating Equations) and subject-specific models (using random effects to capture within-subject correlations) [26].

Interpreting SRM Variance Components

In round-robin designs, the interpretation of variance components provides insights into the architecture of social behavior [20] [24]:

Substantial Actor Variance indicates that individuals display consistent behaviors across different interaction partners, supporting the existence of behavioral traits or "animal personality" in non-human studies [27]. For example, strong actor effects in children's anger expression would suggest that some children are generally more anger-prone regardless of their interaction partner [24].

Significant Partner Variance demonstrates that individuals consistently elicit particular responses from others, revealing social reputations or evocative person-environment correlations. In emotion expression research, partner effects indicate that some children universally elicit more positive or negative emotions from their peers [24].

Prominent Relationship Variance highlights the unique dyadic quality of specific relationships that cannot be explained by either person's general tendencies alone. This component captures truly dyadic phenomena and person × situation interactions [20] [24].

Table 4: Quantitative Evidence for P×S Effects Across Behavioral Domains

| Behavioral Domain | Person Variance | Situation Variance | P×S Variance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 8% | 7% | 17% | [20] |

| Five-Factor Personality Traits | Varies by trait | Varies by trait | Substantial effects reported | [20] |

| Perceived Social Support | Varies by measure | Varies by measure | Strong effects reported | [20] |

| Leadership | Varies by context | Varies by context | Significant effects reported | [20] |

| Task Performance | Varies by task | Varies by task | Substantial effects reported | [20] |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Integration with Behavioral Ecology and Conservation

Variance partitioning approaches have profound implications beyond human research, particularly in behavioral ecology and conservation [27]. By analyzing individual differences in movement behaviors using repeated observations, researchers can quantify:

- Behavioral types: Individual differences in average movement expression (e.g., more active vs. less active individuals)

- Behavioral plasticity: Individual differences in responsiveness to environmental gradients

- Behavioral predictability: Individual differences in residual within-individual variability around mean behavior

- Behavioral syndromes: Correlations among different movement behaviors at the individual level [27]

This approach has revealed remarkable specializations in foraging behaviors in marine mammals and birds, with some populations harboring a mix of foraging specialists and generalists [27]. Such individual differences in movement and predictability can affect an individual's risk to be hunted or poached, opening new avenues for conservation biologists to assess population viability [27].

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Research Applications

In clinical trials and drug development, repeated-measures designs significantly enhance precision in estimating treatment effects by controlling for between-subject variability [25] [26]. This increased precision translates to greater statistical power to detect treatment effects, potentially requiring smaller sample sizes to achieve equivalent power compared to between-subjects designs [26].

The application of these designs is particularly valuable when:

- Investigating how treatments affect individual change patterns over time

- Studying individual differences in treatment response

- Modeling complex dose-response relationships across multiple time points

- Understanding the time course of treatment effects and side effects

For pharmaceutical professionals, these designs provide enhanced sensitivity for detecting treatment effects while simultaneously offering insights into individual differences in therapeutic response, a crucial consideration for personalized medicine approaches.

In individual behavior research, understanding the origins of behavioral variation is paramount. The core challenge lies in disentangling the complex web of influences—intrinsic individual traits, reversible responses to environmental contexts, and measurement error—to arrive at a meaningful biological interpretation. Variance partitioning provides a powerful statistical framework to address this challenge, quantifying the contribution of different sources to the total observed variation in behavioral phenotypes [27]. This protocol details a step-by-step analytical procedure, grounded in linear mixed models, to move from standard regression models to a quantitative calculation of variance components. The methodology is universally applicable, from studies of animal personality in ecology to human behavioral analysis and the assessment of patient-reported outcomes in clinical drug development [28] [27].

Theoretical Foundation: Key Concepts in Variance Partitioning

Defining Variance Components

In behavioral studies, the total observed variance (( \sigma^2_{Total} )) in a measured trait can be partitioned into several key components [27] [7]:

- Among-Individual Variance (( \sigma^2_A )): Represents intrinsic, consistent differences between individuals over time (also known as "animal personality" or behavioral type). This component reflects an individual's average behavioral expression and is quantified as the variance of random intercepts in a mixed model [27].

- Within-Individual Variance (( \sigma^2_W )): Captures reversible behavioral plasticity within a single individual, including fluctuations due to environmental conditions, internal states, and measurement error [27].

- Person × Situation (P×S) Interaction Variance (( \sigma^2_{PxS} )): This crucial component represents individual differences in behavioral plasticity—that is, the extent to which individuals differ in their responsiveness to the same environmental gradient or situation [27] [7].

The Linear Mixed Model Framework

The statistical foundation for variance partitioning is the linear mixed model (LMM). An LMM for a behavioral measurement ( y{ij} ) from individual ( i ) in context ( j ) can be formulated as [2]: [ y{ij} = \beta0 + \beta X{ij} + \alphai + \varepsilon{ij} ] [ \alphai \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2{\alpha}) ] [ \varepsilon{ij} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2{\varepsilon}) ] where ( \beta0 ) is the fixed intercept, ( \beta X{ij} ) represents the fixed effects of measured covariates, ( \alphai ) is the random intercept for individual ( i ) (with variance ( \sigma^2{\alpha} ), representing the among-individual variance), and ( \varepsilon{ij} ) is the residual term (with variance ( \sigma^2{\varepsilon} ), representing the within-individual variance). The total variance is then ( \sigma^2{Total} = \sigma^2{\alpha} + \sigma^2_{\varepsilon} ) [2].

Table 1: Key Variance Components and Their Interpretation in Behavioral Research

| Variance Component | Statistical Interpretation | Biological/Behavioral Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Among-Individual (( \sigma^2_A )) | Variance of random intercepts | Animal personality; consistent behavioral type [27] |

| Within-Individual (( \sigma^2_W )) | Residual variance (after accounting for other effects) | Behavioral plasticity; reversible variation and measurement error [27] |

| P×S Interaction (( \sigma^2_{PxS} )) | Variance of random slopes | Individual differences in behavioral plasticity [27] [7] |

| Repeatability (R) | ( R = \sigma^2A / (\sigma^2A + \sigma^2_W) ) | Proportion of total variance due to consistent individual differences [27] |

Analytical Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive analytical workflow for variance partitioning, from experimental design to final interpretation.

Figure 1: A workflow for variance partitioning analysis, showing key steps from design to reporting.

Step-by-Step Analytical Protocol

Step 1: Experimental Design and Data Collection

Objective: To design a study that allows for the separation of among-individual and within-individual variance.

- Protocol:

- Repeated Measures Design: Collect multiple behavioral measurements from the same individual across different contexts or time points. The number of measurements per individual should be balanced where possible to enhance statistical power and simplify analysis [27] [7].

- Context Standardization: Ensure that all individuals are assessed under the same set of standardized conditions or stimuli (situations) to allow for the estimation of P×S interactions [7].

- Randomization: Randomize the order of stimulus presentation or context exposure to control for order effects.

- Considerations: In drug development, this aligns with the FDA's Process Validation guidance, which mandates understanding the impact of variation (e.g., materials, equipment, operators) on process and product attributes [28].

Step 2: Model Specification

Objective: To formulate a linear mixed model that reflects the experimental design and captures the relevant sources of variation.

- Protocol:

- Basic Model with Random Intercept: Begin by specifying a model that partitions variance into among-individual and within-individual components. [ y{ij} = \beta0 + \alphai + \varepsilon{ij} ] where ( y{ij} ) is the behavior of individual ( i ) in measurement ( j ), ( \beta0 ) is the global mean, ( \alphai ) is the deviation of individual ( i ) from the mean (( \alphai \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2{\alpha}) )), and ( \varepsilon{ij} ) is the residual deviation (( \varepsilon{ij} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2{\varepsilon}) )) [27] [2].