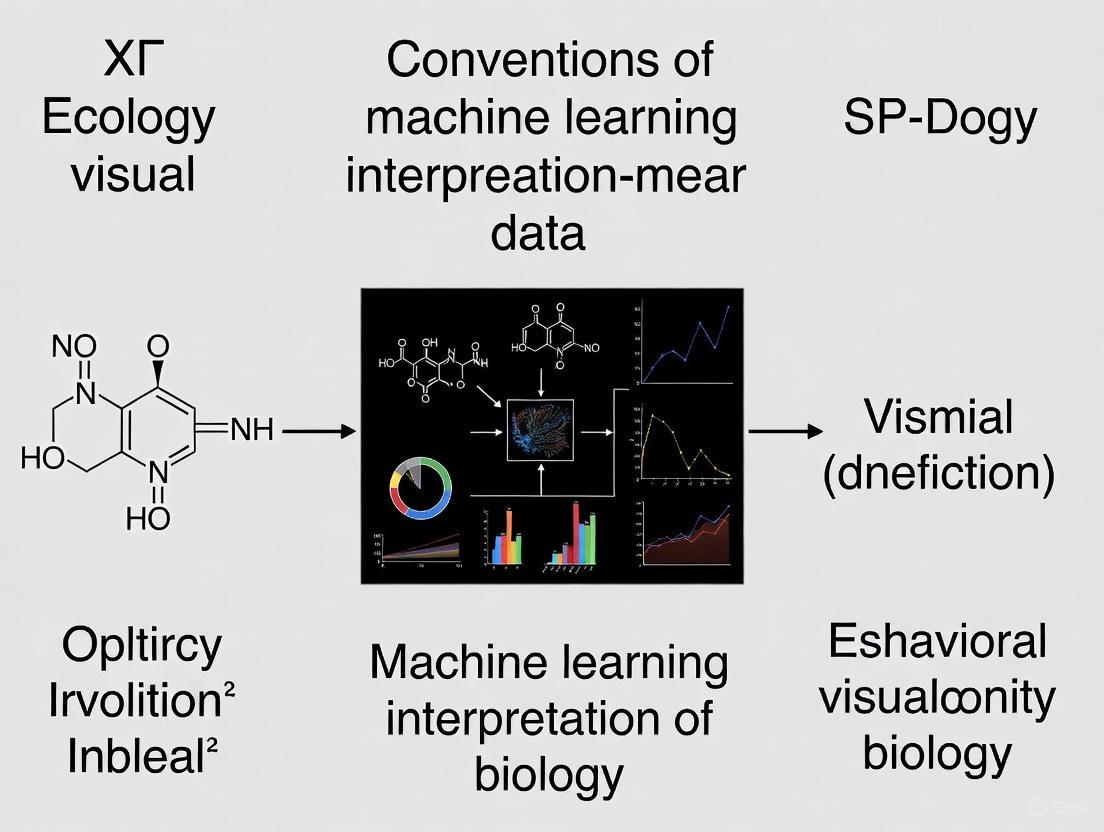

Demystifying the Black Box: Interpretable Machine Learning for Biological Discovery and Drug Development

The adoption of sophisticated machine learning (ML) models in biology and drug discovery is hampered by their 'black box' nature, where internal decision-making processes are opaque.

Demystifying the Black Box: Interpretable Machine Learning for Biological Discovery and Drug Development

Abstract

The adoption of sophisticated machine learning (ML) models in biology and drug discovery is hampered by their 'black box' nature, where internal decision-making processes are opaque. This creates critical challenges for trust, validation, and regulatory compliance. This article provides a comprehensive framework for biological and pharmaceutical researchers to navigate the interpretation of ML models. We explore the foundational concepts of model opacity, survey key explainable AI (XAI) methodologies and their applications in target discovery and biomarker identification, address practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for tools like SHAP and LIME, and establish rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing current best practices and future directions, this guide aims to empower scientists to build more transparent, reliable, and effective ML models that accelerate biomedical innovation.

The Black Box Problem: Why Model Interpretability is Non-Negotiable in Biology

FAQs on Black Box Machine Learning in Biology Research

Q1: What does "black box" mean in the context of machine learning for biology? A: In machine learning, a "black box" describes models where it is difficult to decipher how inputs are transformed into outputs. For neural network potentials (NNPs) used in biology, this means the model provides accurate energy predictions for molecular systems but offers no insight into the nature and strength of the underlying molecular interactions that led to that prediction [1].

Q2: Why is interpretability a critical challenge for machine learning in drug discovery? A: Interpretability is crucial for building trust in model predictions and for scientific validation. A model's accurate prediction could stem from learning true physical properties of the data or from memorizing data artifacts [1]. In high-stakes fields like drug discovery, understanding a model's reasoning is essential before relying on its outputs for developing patient treatments [2] [3].

Q3: What are some common technical issues that can cause a machine learning model to perform poorly? A: Poor performance is often traced back to data quality issues. Common problems include:

- Corrupt, Incomplete, or Insufficient Data: Missing values, mismanaged data, or simply not enough data to train the model effectively [4].

- Overfitting: The model learns the training data too precisely, including its noise, and fails to generalize to new, unseen data [4] [5].

- Underfitting: The model is too simple to capture the underlying trends in the data [4] [5].

- Unbalanced Data: The dataset is skewed towards one class, leading to biased predictions [4].

Q4: Are there techniques to "open" the black box and understand what a model has learned? A: Yes, the field of Explainable AI (XAI) is dedicated to this problem. Techniques like Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) can be applied to complex models. For instance, GNN-LRP can decompose the energy output of a graph neural network into contributions from specific n-body interactions (e.g., 2-body and 3-body interactions in a molecule), providing a human-understandable interpretation of the learned physics [1].

Q5: How can the "lab in a loop" approach improve AI-driven drug discovery? A: The "lab in a loop" is a powerful iterative process. Data from lab experiments is used to train AI models, which then generate predictions about drug targets or therapeutic molecules. These predictions are tested in the lab, generating new data that is used to retrain and improve the AI models. This creates a virtuous cycle that streamlines the traditional trial-and-error approach [2].

Troubleshooting Guides for ML Experiments

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Model Generalization

Symptoms: Your model performs well on training data but poorly on validation or test data.

| Step | Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Your Data | Handle missing values, remove or correct outliers, and ensure the data is balanced across target classes [4]. |

| 2 | Preprocess Features | Apply feature normalization or standardization to bring all features to the same scale [4]. |

| 3 | Select Relevant Features | Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or feature importance scores from algorithms like Random Forest to remove non-contributory features [4]. |

| 4 | Apply Cross-Validation | Use k-fold cross-validation to robustly assess model performance and tune hyperparameters, ensuring a good bias-variance tradeoff [4]. |

Guide 2: Interpreting a Trained Neural Network Potential

Objective: Decompose the energy prediction of a Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based potential into physically meaningful n-body interactions.

Protocol (Using GNN-LRP):

- Train Your Model: Ensure your GNN model for the coarse-grained system (e.g., a fluid or protein) is trained and converged [1].

- Propagate Relevance: Apply the Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) technique backward through the network. LRP decomposes the activation of each neuron into contributions from its inputs, ultimately attributing relevance scores to the input features [1].

- Attribute to Graph Walks: For GNNs, GNN-LRP attributes the model's energy output to "walks" (sequences of edges) on the input graph [1].

- Aggregate into n-body Contributions: Aggregate the relevance scores of all walks associated with a specific subgraph (e.g., a pair or triplet of nodes) to determine the n-body contribution of that subgraph to the total energy [1].

- Validate Physically: Examine the resulting n-body contributions. A well-trained, trustworthy model should display interaction patterns consistent with fundamental physical principles [1].

Experimental Protocols for Interpretation

Protocol: Decomposing NNPs with GNN-LRP

This methodology is based on research that applied Explainable AI (XAI) tools to neural network potentials for molecular systems [1].

1. Research Question: How can we decompose the total potential energy predicted by a black box NNP into human-interpretable, many-body interaction terms?

2. Key Materials & Computational Tools:

- Trained Graph Neural Network Potential: A model trained on molecular simulation data [1].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation Data: Data for the system of interest (e.g., bulk water, a protein like NTL9) to serve as input [1].

- GNN-LRP Implementation: Software tools capable of performing Layer-wise Relevance Propagation on GNN architectures [1].

3. Methodology Details:

- The core of the method is the GNN-LRP technique. It works by propagating the prediction (total energy) backward through the network layers. At each layer, the relevance (R) is redistributed from the output to the inputs using a specific propagation rule [1].

- The process starts at the output node (the predicted energy) and is recursively applied backward through all layers until the input layer is reached. The redistribution rule conserves the total relevance at each layer, so the sum of relevances at one layer equals the sum at the next [1].

- For a GNN, this process eventually attributes relevance scores to walks (w) on the input graph:

R_total = Σ R_w. The relevance of an n-body interaction is then calculated by summing the relevances of all walks that connect the n nodes within the subgraph [1].

4. Expected Outcomes:

- A quantitative decomposition of the total potential energy into 2-body, 3-body, and higher-order interaction terms.

- The interpretation should reveal that a well-trained model has learned physical interactions consistent with chemical knowledge, such as the relative importance of 2-body and 3-body contributions in bulk water [1].

Key Data on ML Challenges & Solutions

Table 1: Common Data-Related Challenges in Biological ML

| Challenge | Description | Potential Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting [4] [5] | Model is too complex and fits the training data too closely, including its noise. | Fails to generalize to new data; low bias but high variance. |

| Underfitting [4] [5] | Model is too simple to capture underlying trends in the data. | Poor performance on both training and new data; high bias but low variance. |

| Data Imbalance [4] | Data is unequally distributed across target classes (e.g., 90% class A, 10% class B). | Model becomes biased towards the majority class, poorly predicting the minority class. |

| Insufficient Data [4] | The dataset is too small for the model to learn effectively. | Leads to underfitting and an inability to capture the true input-output relationship. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for ML Interpretation

| Item | Function in Interpretation Experiments |

|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [1] | The core architecture for defining complex, many-body potentials in molecular systems. |

| Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) [1] | An Explainable AI (XAI) technique used to decompose a model's prediction into contributions from its inputs. |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Model Data [1] | Data from molecular systems where atomistic details are renormalized into beads; used to train and test NNPs. |

| Cross-Validation Framework [4] | A technique to assess model generalizability and select the best model based on a bias-variance tradeoff. |

Trust Deficit in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

FAQ: Why is trust a critical component in Pharma R&D?

Trust is fundamental to a pharma company's ability to deliver on its mission, impacting the quality and effectiveness of its interactions with patients, healthcare providers, regulators, and society at large [6]. The industry's social contract is directly tied to its business value, as its core purpose is to improve patient quality of life [6]. Despite this, the industry consistently struggles with public trust, which can lag behind other health subsectors [6].

FAQ: How does patient distrust directly impact clinical trials?

Patient distrust in pharmaceutical companies can create significant recruitment bias, threatening the external validity and applicability of clinical trial results [7]. A 2020 study found that 35.5% of patients surveyed distrusted pharmaceutical companies, and this distrust was associated with an unwillingness to participate in pre-marketing and industry-sponsored trials [7]. This can lead to the under-representation of specific patient categories, such as women, in clinical research [7].

Table: Factors Associated with Patient Distrust in Pharmaceutical Companies

| Factor | Impact on Distrust | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | Increased likelihood of distrust | p=0.042 [7] |

| Professional Inactivity | Increased likelihood of distrust | p=0.007 [7] |

| Not Knowing Name of Disease | Increased likelihood of distrust | p=0.010 [7] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Operationalizing Trust in Pharma

To build and maintain trust, companies can focus on a "hierarchy of trust" composed of three building blocks [6]:

- Foundation: Benefits of Medicines. Ensure an absolute commitment to producing safe, effective, and high-quality drugs that comply with both the spirit and letter of regulations [6].

- Second Level: Integrity. Move beyond minimum ethical standards by embracing patient centricity. This involves ensuring patients have affordable access to the right medicine and managing the entirety of their health experience [6].

- Third Level: Social Contract. Take responsibility for the impact of products and business operations on society, communities, and the environment through robust ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility), and DE&I (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) efforts [6].

Hidden Bias in Machine Learning for Biological Research

FAQ: How can bias infiltrate AI/ML models used in R&D?

Bias is not merely a technical issue but a societal challenge that can be introduced at multiple stages of the AI pipeline [8]. AI systems are built by humans and trained on human-generated data, meaning they can reflect both conscious and unconscious human biases [9]. The core strength of AIS is their ability to identify patterns in data, but they may find new correlations without considering whether the basis for those relationships is fair or unfair [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Common Biases

Researchers must be vigilant for specific types of bias that can compromise model validity and lead to unfair outcomes.

Table: Common Types of Bias in AI and Their Mitigation

| Bias Type | Description | Potential Impact in Biology/Pharma | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Bias [8] | Training data is not representative of the real-world population. | A disease prediction model trained only on data from a specific ethnic group may fail to generalize. | Ensure training datasets include a wide range of perspectives and demographics [8]. |

| Confirmation Bias [8] | The system reinforces historical prejudices in the data. | A drug discovery algorithm may overlook promising compounds that do not fit established patterns. | Implement fairness audits and adversarial testing [8]. |

| Measurement Bias [8] | Collected data systematically differs from the true variables of interest. | Basing patient success predictions only on those who completed a trial, ignoring dropouts. | Carefully evaluate data collection methods and variable selection [9]. |

| Stereotyping Bias [8] | AI systems reinforce harmful stereotypes. | An model might associate certain diseases primarily with one gender based on historical data. | Diversify training datasets and use bias detection tools [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Bias Auditing in ML-Based Research

The following workflow outlines a continuous process for identifying, diagnosing, and mitigating bias in machine learning projects for biological research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Bias-Aware ML Research

Table: Essential Resources for Mitigating Bias in Biological ML

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fairness Metrics (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds) | Quantify model performance and outcome differences across subgroups [9]. | Auditing a clinical trial patient selection model for disproportionate exclusion of a demographic. |

| Adversarial Debiasing | A technique where a model is trained to be immune to biases by "attacking" it with adversarial examples [8]. | Removing protected attribute information (like gender) from a disease prediction model while retaining predictive power. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques | Provide post-hoc explanations for model predictions, increasing transparency [8]. | Understanding which genomic features a black-box model used to classify a tumor subtype. |

| Synthetic Data Generation (e.g., SMOTE) | Algorithmically generates new data points to address class imbalance in datasets [10]. | Augmenting a rare disease dataset to improve model generalization and prevent bias toward the majority class. |

Regulatory Hurdles in Drug Development

FAQ: What are the most common regulatory pitfalls in the drug development lifecycle?

Drug development is a highly complex and regulated process with a failure rate in clinical trials exceeding 90%, often due to insufficient safety data, efficacy concerns, or regulatory non-compliance [11]. Common pitfalls include:

- Inadequate Clinical Trial Design: Designs that lack clearly defined endpoints or have insufficient patient enrollment can lead to requests for additional studies or outright rejection [11].

- Global Regulatory Variability: Differences in approval timelines, documentation, and clinical trial expectations across regions (e.g., FDA, EMA, PMDA) complicate global drug submissions [11].

- Manufacturing Non-Compliance: Failure to adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) can result in approval delays, production halts, or post-market recalls, even for an effective drug [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating Evolving Regulatory Landscapes

With regulatory frameworks continuously updating, a proactive and strategic approach is essential for success.

- Engage Regulatory Agencies Early: Seek input from agencies like the FDA and EMA during early development stages to clarify expectations and gain insight into study design [11]. Pre-IND meetings are a valuable forum for this.

- Ensure Meticulous Documentation: Regulatory agencies require detailed documentation of all data, from preclinical toxicology to manufacturing protocols. Incomplete or poorly documented submissions are a major cause of delays [11].

- Strengthen Global Strategy: Consider parallel submissions with other agencies (e.g., EMA, Health Canada) to diversify approval pathways and reduce dependence on a single regulator's timeline [12].

- Plan for Financial and Operational Adjustments: Build extra time into development timelines to account for potential regulatory delays and adjust financial models accordingly [12].

Experimental Protocol: Proactive Regulatory Submission Strategy

The following diagram visualizes a strategic workflow for preparing a regulatory submission, incorporating key steps to mitigate delays.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Dataset Bias

This guide helps researchers diagnose and correct for common types of dataset bias that can compromise drug efficacy predictions.

Q1: My AI model for predicting trial approval shows high accuracy in validation but fails dramatically on new trial data. What could be wrong?

This is a classic sign of confounding bias or selection bias in your training data.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Run a Partial Confounder Test: Apply statistical tests, like the partial confounder test, to quantify confounding bias for variables like trial phase, specific diseases, or pharmaceutical company sponsors. This test probes the null hypothesis that your model is unconfounded [13].

- Analyze Feature Distributions: Check if the distribution of key features (e.g., trial locations, patient demographics, drug mechanisms) differs significantly between your training set and the new data.

- Inspect Model Explanations: Use Explainable AI (XAI) tools to see which features your model is relying on for predictions. Over-reliance on features that are spuriously correlated with success in the training data is a red flag [14] [15].

Solution:

- Causal Machine Learning (CML): Integrate CML techniques to estimate treatment effects from Real-World Data (RWD). Methods like advanced propensity score modeling, targeted maximum likelihood estimation, and doubly robust inference can help mitigate confounding [16].

- Data Augmentation: Enrich your dataset with synthetic or carefully sourced additional data to improve the representation of under-represented subgroups or trial types [14].

Q2: The AI-predicted efficacy of our drug candidate appears significantly over-optimistic compared to early clinical results. What should I investigate?

This often points to label bias or representation bias.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Audit Training Data Labels: Verify the ground-truth data for your model's "efficacy" label. Models trained on datasets where "success" is defined by passing a trial phase (the label) can inherit biases if that label is influenced by factors other than true biological efficacy, such as trial design quality or strategic company decisions to terminate trials for financial reasons [17].

- Check for Demographic Gaps: Investigate if your training data suffers from a "gender data gap" or under-represents certain racial or ethnic groups. AI models trained on such data will perform poorly for the excluded populations, leading to skewed global efficacy predictions [14].

Solution:

- Refine Label Definitions: Work with clinical experts to ensure labels accurately reflect the biological efficacy you intend to predict.

- Implement XAI for Auditing: Use explainable AI to audit the model's decision-making process, highlighting when predictions are disproportionately influenced by a single demographic or non-biological factor [14].

Q3: My model for adverse event prediction performs well overall but is highly unreliable for a specific patient subgroup. How can I fix this?

This indicates a lack of generalizability due to biased sampling.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Identify the Subgroup: Use model error analysis tools to pinpoint the patient characteristics (e.g., specific comorbidities, age range, genetic markers) for which performance degrades.

- Analyze Subgroup Prevalence in Data: Quantify how well this patient subgroup is represented in your original training dataset. It is likely severely under-represented [16].

Solution:

- Stratified Sampling: Re-sample your training data to ensure adequate representation of the problematic subgroup.

- Subgroup-Specific Modeling: Use CML and RWD to identify patient subgroups with varying treatment responses. This allows for the development of more precise, subgroup-specific models [16].

Experimental Protocols for Bias Detection

Protocol 1: Partial Confounder Test for Model Validation

Objective: To statistically test whether a trained predictive model's outputs are independent of a potential confounder variable, given the target variable [13].

Materials:

- A trained predictive model.

- Test dataset with observed confounder variables

C(e.g., trial phase, patient demographic data). - The

mlconfoundPython package or equivalent.

Methodology:

- Define Variables: For your model, define

Y(the target variable, e.g., trial approval),Ŷ(the model's prediction), andC(the confounder variable to test). - Set Hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀):

Ŷis independent ofCgivenY(the model is not confounded). - Alternative Hypothesis (H₁):

Ŷis not independent ofCgivenY(the model is confounded).

- Null Hypothesis (H₀):

- Execute Test: Run the partial confounder test, which uses a conditional permutation approach to test for conditional independence without requiring model retraining [13].

- Interpret Result: A statistically significant p-value (e.g., p < 0.05) leads to a rejection of H₀, indicating that your model's predictions are likely confounded by variable

C.

Protocol 2: XAI-Driven Bias Audit in Efficacy Predictors

Objective: To use Explainable AI to uncover which features a model uses for efficacy prediction and identify potential spurious correlations.

Materials:

- A trained model for drug efficacy or trial approval prediction [17].

- A representative dataset of clinical trial features (e.g., from TrialBench) [17].

- An XAI tool capable of generating feature attribution maps (e.g., SHAP, LIME).

Methodology:

- Generate Explanations: For a set of predictions, use the XAI tool to generate a feature importance score for each input feature (e.g., drug structure, disease code, eligibility criteria).

- Cluster by Outcome: Separate the explanations into two groups: those for predicted "successful" trials and those for predicted "failed" trials.

- Identify Divergent Features: Analyze the top features for each cluster. Look for features that are strong predictors in the model but have no plausible biological link to efficacy (e.g., "trial conducted in a specific country"). These are candidates for spurious correlations driven by dataset bias [15].

- Validate Findings: Correlate the identified features with known confounders and, if possible, run ablation studies to see how model performance changes when these features are removed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Resources for Bias-Aware AI Modeling in Drug Discovery

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| TrialBench Datasets [17] | Provides 23 curated, multi-modal, AI-ready datasets for clinical trial prediction (e.g., duration, approval, adverse events). Offers a standardized benchmark to reduce data collection bias. |

| mlconfound Package [13] | A Python package implementing the partial confounder test, providing a statistical method to quantify confounding bias in trained machine learning models. |

| Causal Machine Learning (CML) Methods [16] | A suite of techniques (e.g., doubly robust estimation, propensity score modeling with ML) for deriving valid causal estimates from observational Real-World Data, correcting for confounding. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Frameworks [14] [15] | Tools that provide transparency into AI decision-making, allowing researchers to audit models, verify biological plausibility, and identify reliance on biased features. |

| Real-World Data (RWD) [16] | Data derived from electronic health records, wearables, and patient registries. Used to complement controlled trial data, enhance generalizability, and identify subgroup-specific effects. |

Bias Identification and Mitigation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for identifying and mitigating dataset bias in drug efficacy prediction models.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the most common source of bias in AI-driven drug efficacy predictions? A: Confounding bias is a pervasive issue. This occurs when an external variable influences both the features of the drug/trial and the outcome (efficacy). For example, if a dataset contains many trials for a specific disease from a single, highly proficient sponsor, the model may learn to associate that sponsor with success rather than the drug's true efficacy [13] [16].

Q: Can't we just use more data to solve the bias problem? A: Not necessarily. Simply adding more data can amplify existing biases if the new data comes from the same skewed sources. The key is not just the quantity, but the diversity and representativeness of the data. Incorporating balanced, real-world data and using techniques like causal machine learning are more effective strategies [14] [16].

Q: How does Explainable AI (XAI) help with dataset bias? A: XAI acts as a "microscope" into the AI's decision-making. By revealing which data features the model used to make a prediction, XAI allows researchers to identify when a model is relying on spurious correlations (e.g., a specific clinical site) instead of biologically relevant signals (e.g., a drug's molecular structure). This transparency is the first step toward correcting the bias [14] [15].

Q: Are there regulatory guidelines for addressing AI bias in drug development? A: Yes, regulatory landscapes are evolving. The EU AI Act, for instance, classifies AI systems in healthcare and drug development as "high-risk," mandating strict requirements for transparency and accountability. While AI used "solely for scientific R&D" may be exempt, the overarching trend is toward requiring explainability and bias mitigation to ensure safety and efficacy [14].

Q: What is the role of causal machine learning versus traditional ML here? A: Traditional ML excels at finding correlations for prediction but struggles with "what if" questions about interventions. Causal ML is specifically designed to estimate treatment effects and infer cause-and-effect relationships from complex data, making it far more robust for predicting the true efficacy of a drug by actively accounting for and mitigating confounding factors [16].

For researchers in biology and drug development, artificial intelligence has evolved from a powerful tool to a regulated technology. The EU AI Act, the world's first comprehensive legal framework for artificial intelligence, establishes specific requirements for AI systems based on their potential impact on health, safety, and fundamental rights [18] [19]. For your work with black box machine learning models in biological research, this legislation creates both obligations and opportunities.

The Act takes a risk-based approach, categorizing AI systems into four tiers [18] [20]. Many AI applications in healthcare, pharmaceutical research, and biological analysis fall into the "high-risk" category, triggering strict requirements for transparency, human oversight, and robust documentation [19]. This technical support center provides the essential guidance and troubleshooting resources you need to align your research with these emerging regulatory standards while advancing your scientific objectives.

FAQs: Explainable AI in Biological Research

Q1: How does the EU AI Act specifically affect our use of machine learning models for drug discovery?

The EU AI Act affects your drug discovery workflows primarily if they involve AI systems classified as high-risk. This includes models used for credit scoring, recruitment, healthcare applications, or critical infrastructure [20]. In practice, if your AI models influence decisions about drug efficacy, toxicity predictions, or patient treatment options, they likely fall under the high-risk category [18] [19].

For these systems, you must implement comprehensive risk management systems, maintain detailed technical documentation, ensure human oversight, and use high-quality, bias-mitigated training data [19] [20]. The Act also mandates transparency obligations, requiring you to create and maintain up-to-date model documentation and provide relevant information to users upon request [18].

Q2: What are the most common pitfalls in making black-box biological models interpretable?

The most frequent challenges include:

- Over-reliance on performance metrics while ignoring explainability needs [21]

- Failure to validate whether explanatory features align with biological mechanisms [22]

- Insufficient documentation of training data characteristics and limitations [18]

- Assuming model interpretability methods (like attention weights) provide biologically meaningful explanations without validation [21]

A particularly problematic scenario occurs when models achieve high accuracy by learning from artifactual or biased features in the data rather than biologically relevant patterns [22]. The SWIF(r) framework and similar approaches help detect when models operate outside their reliable domain [22].

Q3: What documentation is now legally required for our published biological AI models?

Under the EU AI Act, high-risk AI systems require Annex IV documentation [20]. For biological research, this translates to:

- Detailed technical documentation proving how your model works and why it's safe [19]

- Training data characteristics and methodologies [18]

- Risk assessment reports and mitigation strategies [18]

- Human oversight mechanisms implemented in your workflow [19]

- Performance benchmarks and validation results [18]

- Post-market monitoring plans for ongoing assessment [20]

Additionally, you must register high-risk systems in the EU's public AI database and maintain records for 10 years after market placement [20].

Q4: Are there specific explainability techniques that better satisfy regulatory requirements?

Yes, techniques that provide feature importance scores, counterfactual explanations, and model-agnostic interpretations tend to better satisfy regulatory requirements [21]. The EU AI Act emphasizes transparency and explainability without prescribing specific technical methods [18].

For biological applications, Interpretable Machine Learning (IML) methods that reveal feature importance help connect results with existing biological theory [21] [22]. Methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) are particularly valuable because they provide both local and global explanations [21]. Generative classifiers like SWIF(r) offer inherent interpretability through their probability-based framework [22].

Table: Explainability Techniques for Biological AI

| Technique | Best For | Regulatory Strengths | Biological Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Importance | Genomic sequence analysis, biomarker discovery | Clearly identifies decision drivers | Enables hypothesis generation for experimental validation |

| Attention Mechanisms | Protein structure prediction, sequence classification | Provides localization of important features | Requires biological validation to ensure relevance [21] |

| Counterfactual Explanations | Drug efficacy prediction, variant interpretation | Shows minimal changes to alter outcomes | Supports understanding of causal biological mechanisms |

| Model-Specific Explanations | Decision trees, rule-based systems | Naturally interpretable structure | May sacrifice predictive performance for interpretability [21] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance Doesn't Align with Biological Reality

Symptoms: Your model achieves high accuracy metrics but identifies features without biological plausibility, or performs poorly on slightly novel data.

Solution: Implement the following workflow to diagnose and address the issue:

- Conduct feature importance analysis using SHAP or LIME to identify what features drive predictions [21]

- Compare identified features with established biological knowledge through literature review

- Apply domain expertise to assess whether the features have plausible biological mechanisms

- Utilize reliability scores like the SWIF(r) Reliability Score (SRS) to detect when models face unfamiliar data patterns [22]

- Iteratively refine training data to eliminate artifacts and improve biological relevance

Problem: Inadequate Documentation for Regulatory Compliance

Symptoms: Missing model provenance, insufficient training data documentation, inability to explain model decisions to regulators.

Solution: Develop comprehensive documentation addressing these key areas:

Table: Essential Documentation Framework for Biological AI

| Documentation Category | Specific Requirements | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Model Characteristics | Capabilities, limitations, intended use cases | Model cards, datasheets [18] |

| Training Data | Datasets characteristics, preprocessing methods, bias assessments | Data statements, provenance tracking [18] |

| Performance Metrics | Benchmark results across diverse biological contexts | Cross-validation protocols, external validation [23] |

| Explainability Methods | Techniques used to interpret model decisions | SHAP, LIME, feature importance scores [21] |

| Risk Management | Identified risks, mitigation strategies, monitoring plans | Risk assessment frameworks, adverse event reporting [20] |

Problem: Handling Novel Biological Data Not Represented in Training

Symptoms: Your model encounters genetic variants, cellular structures, or biological patterns not present in training data, leading to unreliable predictions.

Solution: Implement a reliability scoring system to detect and handle novel patterns:

The SWIF(r) Reliability Score (SRS) framework is particularly valuable here, as it measures the trustworthiness of classifications for specific instances by assessing similarity between test data and training distributions [22].

Experimental Protocols for Explainable Biological AI

Protocol 1: Validating Model Explanations with Biological Experiments

Purpose: To experimentally verify that features identified as important by explainable AI methods have genuine biological significance.

Materials:

- Trained AI model with explainability interface

- Relevant biological assay systems (cell culture, animal models, etc.)

- Feature importance outputs (SHAP, LIME, or similar)

- Standard laboratory equipment for your biological domain

Procedure:

- Identify top predictive features using your explainability method of choice

- Design perturbation experiments that specifically target these features (e.g., CRISPR for genetic features, inhibitors for pathway features)

- Execute controlled experiments measuring the biological outcomes of these perturbations

- Compare model predictions with experimental results to validate causal relationships

- Refine model based on discrepancies between predicted and actual biological effects

This validation is crucial for regulatory compliance, as it demonstrates that your model's decision-making aligns with biological mechanisms rather than artifacts [21] [22].

Protocol 2: Implementing Human-in-the-Loop Oversight

Purpose: To establish compliant human oversight mechanisms for high-risk biological AI systems as required by Article 50 of the EU AI Act [19].

Materials:

- AI system with configurable confidence thresholds

- Domain expert biologists/physicians

- Documentation system for recording human oversight actions

- Disagreement resolution protocol

Procedure:

- Define risk thresholds that trigger human review (e.g., low confidence scores, novel patterns)

- Establish review protocols specifying when and how human experts intervene

- Implement override capabilities allowing experts to modify or reject model decisions

- Document all interventions and their rationales for regulatory audit trails

- Continuously update models based on expert feedback to improve performance

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Explainable AI Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Explainable AI | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| SWIF(r) Framework | Generative classifier with built-in reliability scoring | Population genetics, selection detection [22] |

| SHAP/LIME Libraries | Model-agnostic explanation generation | Feature importance in any biological ML model [21] |

| Benchmark Datasets | Standardized performance assessment | 140 datasets across 44 DNA analysis tasks [24] |

| Proteome Analyst (PA) | Custom predictor with explanation features | Protein function prediction, subcellular localization [25] |

| Adversarial Testing Tools | Identifying model vulnerabilities and limitations | Compliance with EU AI Act security requirements [18] |

Compliance Framework Under the EU AI Act

The EU AI Act establishes a phased implementation timeline with specific obligations for high-risk AI systems [18] [19]:

Key Compliance Requirements:

Transparency Obligations: Create and maintain up-to-date model documentation, provide information to users upon request, disclose external influences on model development [18]

Risk Management: Conduct pre-deployment risk assessments, implement mitigation strategies, establish incident reporting workflows [18] [20]

Data Governance: Ensure training data is lawfully sourced, high-quality, and representative; implement copyright compliance [18]

Human Oversight: Design systems with appropriate human intervention points, particularly for critical decisions in drug discovery and healthcare applications [19]

Technical Robustness: Protect against breaches, unauthorized access, and other security threats; ensure accuracy and reliability [18]

The EU AI Act represents a fundamental shift in how AI systems must be developed and deployed in biological research. Rather than viewing these requirements as constraints, forward-thinking research teams can leverage them to build more robust, reliable, and biologically meaningful models. By implementing the explainability techniques, validation protocols, and documentation practices outlined in this guide, your research can both advance scientific understanding and meet emerging regulatory standards.

The integration of explainable AI principles into your biological research workflow ensures that your models not only predict accurately but also provide insights that align with biological mechanisms—creating value that extends beyond compliance to genuine scientific advancement.

FAQs: Choosing and Using Models in Biological Research

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an interpretable model and a black-box model?

A: The difference lies in the transparency of their internal decision-making processes.

- Interpretable (White-Box) Models are characterized by their transparent internal logic, allowing researchers to comprehend exactly how input features lead to a prediction. Common examples include Linear Regression, Logistic Regression, and Decision Trees. Their structure is simple and explainable by design [26].

- Black-Box Models are those where the internal logic is too complex or opaque for direct human interpretation. While they can capture complex, non-linear relationships in data, it is difficult to understand how they arrive at a specific output. Examples include Random Forests, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs), and Neural Networks [26] [27].

Q2: When should I prioritize using an interpretable model in my biological research?

A: You should prioritize interpretable models in the following scenarios, especially when your research has high-stakes implications [26]:

- Small Datasets or Early-Stage Prediction: When you have limited data, such as making predictions from early experimental signals (e.g., initial biomarker readings).

- Regulatory and Trust Needs: When you need to justify decisions for regulatory submissions (e.g., to the FDA) or to build trust with clinical collaborators [27] [28].

- Integrating Domain Knowledge: When you need to easily encode existing biological knowledge or hard constraints into the model.

- Real-Time Requirements: When inference speed is critical due to computational resource limitations.

Q3: What methods exist to explain a black-box model after it has been trained?

A: Several post-hoc (after-training) explanation methods can help you interpret black-box models [27] [29]:

- SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP): A method based on cooperative game theory that assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction [27].

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Explains individual predictions by approximating the black-box model locally with an interpretable model [29].

- Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs): Show the relationship between a feature and the predicted outcome while marginalizing the effects of all other features [29].

- Garson's Algorithm: For Neural Networks, this method dissects the model's connection weights to determine the relative importance of input predictors [29].

Q4: I've trained a neural network for a classification task. How can I identify which input features are most important?

A: You can use Garson's Algorithm to determine the relative importance of each input feature. This algorithm works by dissecting the model's connection weights. It identifies all connections between each input feature and the final output, then pools and scales these weights to generate a single importance value for each feature, providing insight into which inputs the model relies on most [29].

The workflow and output for this method can be visualized as follows, showing how the neural network's internal weights are analyzed to produce a feature importance plot:

Q5: My complex model is performing well but is hard to explain. Must I choose between accuracy and interpretability?

A: Not necessarily. Hybrid modeling approaches are increasingly popular to combine the strengths of both model types [26]:

- Stage-wise Switching: Use a simple, interpretable model for early-stage predictions when data is sparse, and switch to a more complex black-box model as more data becomes available.

- Model Distillation: Train a high-performing black-box model, then use its predictions to train a simpler, interpretable "surrogate" model that approximates its behavior.

- Ensemble Models: Combine predictions from both interpretable and black-box models to improve accuracy and robustness.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Poor with Limited Early-Stage Data

Symptoms: Low accuracy and high variance in predictions during the initial phases of an experiment or when only a few data points are available.

Solution:

- Use an Interpretable Model: Start with a simple model like Logistic Regression or a Decision Tree, which requires less data to train effectively [26].

- Incorporate Domain Heuristics: Embed existing biological knowledge as rules or constraints into your model. For example, a heuristic could be: "If the expression level of biomarker X is below threshold Y, the outcome is negative" [26].

- Apply Feature Selection: Use a principled method like the Holdout Randomization Test (HRT). The HRT is a model-agnostic approach that produces a valid p-value for each feature, helping you identify the most important variables with controlled false discovery rates before building your final model [30].

Problem: Difficulty Interpreting a Neural Network's Behavior

Symptoms: You have a trained neural network with good predictive performance, but you cannot understand how it uses specific inputs to make decisions.

Solution:

- Perform a Sensitivity Analysis with Lek's Profile: This method helps you explore the relationship between an outcome variable and a specific predictor by holding all other predictors at constant values (e.g., at their minimum, 20th percentile, and maximum values). This reveals how the model's output changes in response to a single input [29].

- Generate Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs): A more generic version of a sensitivity analysis, PDPs visualize the marginal effect of one or two features on the predicted outcome [29].

- Use LIME for Local Explanations: For a specific prediction, use LIME to create a locally faithful interpretable model (like a linear model) that explains why the black-box model made that particular decision [29].

The following workflow outlines the steps for using these interpretation techniques:

Experimental Protocols for Model Interpretation

Protocol 1: The Holdout Randomization Test (HRT) for Feature Selection

Objective: To perform statistically sound feature selection using any black-box predictive model while controlling the false discovery rate [30].

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table below.

Procedure:

- Split Data: Partition your dataset into a training set and a holdout validation set.

- Train Model: Train your chosen predictive model (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Network) on the training set.

- Establish Baseline Performance: Calculate the model's performance (e.g., error rate) on the holdout validation set.

- Randomize and Compare: For each feature

jof interest:- Create a modified copy of the holdout validation set where the values for feature

jare randomly shuffled, breaking any relationship betweenjand the outcome. - Calculate the model's performance on this randomized dataset.

- Repeat the randomization and evaluation process many times (e.g., 100 times) to build a null distribution of performance metrics for feature

j.

- Create a modified copy of the holdout validation set where the values for feature

- Calculate P-value: The p-value for feature

jis the proportion of randomized evaluations where the model performance was better than or equal to the baseline performance established in Step 3. A low p-value indicates the model's performance significantly degrades when the feature is randomized, suggesting it is important.

Protocol 2: Lek's Profile Method for Neural Network Interpretation

Objective: To understand the functional relationship between a specific continuous input variable and the output of a neural network [29].

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table below.

Procedure:

- Prepare Data: Select a trained neural network model and the continuous input variable of interest.

- Define Contexts: Hold all other input variables at constant values. Typically, this is done at several levels: their minimum, 20th, 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles, and maximum.

- Generate Predictions: Across the range of the variable of interest, generate the model's predicted output for each of the constant value contexts defined in Step 2.

- Visualize: Plot the predicted output against the values of the input variable of interest, with a separate line for each context (the different percentiles). This plot reveals how the relationship between the input and output changes depending on the values of the other variables, highlighting potential interactions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key software tools and packages for model interpretation.

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Brief Description of Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP [27] | Explanation Library | Quantifies the contribution of each feature to a single prediction for any model. Ideal for local interpretability. |

| LIME [29] | Explanation Library | Creates local surrogate models to explain individual predictions of any black-box classifier or regressor. |

| NeuralNetTools [29] | R Package | Provides various functions for visualizing and interpreting neural networks, including garson() for variable importance and lekprofile() for sensitivity analysis. |

| caret [29] | R Package | A comprehensive framework for building and tuning machine learning models, including neural networks and interpretable models, facilitating standardized experimentation. |

| nnet [29] | R Package | Fits single-hidden-layer neural networks, a fundamental building block for creating models for interpretation. |

| HRT Framework [30] | Statistical Method | A model-agnostic framework for conducting the Holdout Randomization Test, providing p-values for feature importance. |

Model Selection Guide

Table 2: A comparative summary of interpretable vs. black-box models to guide selection for biological research problems.

| Criterion | Interpretable Models (White-Box) | Black-Box Models |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | High: Easy to understand feature influence and model logic [26]. | Low: Requires external explanation tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) [26] [27]. |

| Data Requirement | Low to Moderate: Can be effective with smaller datasets [26]. | High: Especially for deep learning models; requires large amounts of data [26]. |

| Handling of Noise | Moderate to High: Particularly robust when using hand-crafted, domain-knowledge rules [26]. | Variable: Can be brittle and overfit if not trained with diverse, noisy data [26]. |

| Inference Speed | Fast: Typically involves few mathematical operations [26]. | Variable: Can be slow, depending on model depth and size (e.g., deep neural networks) [26]. |

| Performance in Early-Scenarios | Strong: Particularly when domain knowledge is encoded into the model [26]. | Variable: May underperform due to a lack of sufficient signal in sparse data [26]. |

XAI in Action: Key Methods and Their Transformative Biological Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I'm getting inconsistent explanations from LIME for the same protein sequence data. Is this a bug? No, this is a known characteristic of LIME. LIME generates explanations by creating perturbed versions of your input sample and learning a local, interpretable model. The inherent randomness in the perturbation process can lead to slightly different explanations each time. For biological sequences, ensure you set a random state for reproducibility and consider running LIME multiple times to observe the most stable features. For more consistent, theory-grounded explanations, complement your analysis with SHAP [31] [32].

Q2: When analyzing gene expression data, SHAP is extremely slow. How can I improve performance?

SHAP can be computationally intensive, especially with high-dimensional biological data. For tree-based models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost), use shap.TreeExplainer, which is optimized for speed [33]. For other model types, consider the following:

- Subset your data: Calculate SHAP values on a representative subset of your data or use a background dataset of low-dimensional representations from your autoencoder.

- Approximate methods: For deep learning models, use

shap.GradientExplainerorshap.DeepExplainer(for DeepSHAP) which are faster than kernel-based methods [34]. - Hardware: Utilize GPUs for acceleration where possible.

Q3: How do I choose between a global explanation and a local explanation for my model predicting cell states? The choice depends on your biological question.

- Use global explanation methods (e.g., SHAP summary plots, DALEX model-level feature importance) to understand your model's overall behavior—for instance, to identify which genes, on average, are most influential in predicting all cell states [31] [35]. This is useful for hypothesis generation and model debugging.

- Use local explanation methods (e.g., LIME, SHAP force plots, DALEX prediction breakdown) to understand why the model made a specific prediction for a single cell or patient sample [31] [36]. This is crucial for validating a model's decision for a particular case in a clinical or diagnostic context. A complete analysis often involves both.

Q4: Can I use these tools on a protein language model to find out which amino acids are important for function?

Yes, this is an active research area. Standard feature attribution methods can be applied. For instance, you can use SHAP's GradientExplainer or LIME on the input sequence to estimate the importance of individual amino acid positions [34]. Furthermore, novel techniques like sparse autoencoders are being developed to directly "open the black box" of these models, identifying specific nodes in the network that correspond to biologically meaningful features like protein families or functional motifs [37] [38].

Q5: My DALEX feature importance ranking contradicts the one from SHAP. Which one should I trust? It is common for different methods to yield different rankings because they measure importance differently. SHAP bases its values on a game-theoretic approach, fairly distributing the "payout" (prediction) among all "players" (features) [31] [33]. DALEX's default model-level feature importance, on the other hand, measures the drop in model performance (e.g., loss increase) when a single feature is permuted [36] [35]. Instead of choosing one, investigate the discrepancy:

- It may reveal feature interactions and dependencies that one method captures better than the other.

- Validate the findings against known biology; the method whose results are more biologically plausible for your system may be more appropriate.

- The consensus from using multiple methods provides a more robust view than relying on a single one [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable and Noisy LIME Explanations

Problem: LIME explanations vary significantly with each run on the same genomic or clinical data point, making the results unreliable.

Diagnosis: This instability is often due to the random sampling process LIME uses to create perturbed datasets around your instance.

Solution:

- Set a Random Seed: Always set the

random_stateparameter in theLimeTabularExplainerinitialization to ensure reproducibility. - Increase Sample Size: Increase the number of perturbed samples LIME generates using the

num_samplesparameter in theexplain_instancemethod. A larger sample size (e.g., 5000 instead of the default 1000) can stabilize the local model, at the cost of computation time. - Feature Selection: If your data is very high-dimensional (e.g., from single-cell RNA-seq), perform feature selection before modeling or adjust LIME's

feature_selectionparameter to 'auto' or 'lasso_path' to get a sparser, more stable explanation. - Verify with SHAP: Use SHAP to explain the same instance. If both LIME (with a random seed) and SHAP highlight the same top features, you can have greater confidence in the result [31] [32].

Issue 2: SHAP Memory Overflow with Large Biological Datasets

Problem: The Python kernel crashes or runs out of memory when calculating SHAP values for large datasets, such as whole-genome sequences or large patient cohorts.

Diagnosis: SHAP value calculation, especially for model-agnostic methods like KernelSHAP, has a high computational and memory complexity.

Solution:

- Use the Right Explainer:

- Calculate on a Subset: Compute SHAP values on a strategically chosen subset of your data. This could be a random sample or a cluster centroids that represent the overall data distribution.

- Batch Computation: For very large datasets, calculate SHAP values in batches and aggregate the results.

- Approximate with DALEX: As an alternative, use DALEX's model-level feature importance, which is based on permutation and can be less memory-intensive for an initial global analysis [36].

Issue 3: Interpreting Model Predictions with Complex Interaction

Problem: You suspect that your model's predictions are driven by interactions between features (e.g., gene-gene interactions), but standard feature importance methods only show main effects.

Diagnosis: Most feature importance methods show the main effect of a feature. Detecting interactions requires specific techniques.

Solution:

- SHAP Dependency Plots: Use

shap.dependence_plotto visualize the effect of a single feature across its range. If the SHAP values for a feature show a spread in the vertical direction for a given value, it suggests interactions with other features. You can color these plots by a second feature to identify the interacting partner [39]. - DALEX Three-Panel Plots: Use DALEX's

model_profilefunction with thetype = 'conditional'or'accumulated'to create Accumulated Local Effect (ALE) plots. ALE plots are unbiased by interactions and can more clearly show the pure effect of a feature [36] [35]. - SHAP Interaction Values: For tree-based models,

TreeExplainercan directly calculate SHAP interaction values usingshap.TreeExplainer(model).shap_interaction_values(X). This provides a matrix of the interaction effects for every pair of features for every prediction [33].

Comparative Analysis of XAI Tools

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of SHAP, LIME, ELI5, and DALEX for biological data analysis.

| Feature | SHAP | LIME | ELI5 | DALEX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Game-theoretic Shapley values [31] [33] | Local surrogate models [31] [33] | Unified API for model inspection [33] | Model-agnostic exploration and audit [36] |

| Explanation Scope | Local & Global [31] [33] | Primarily Local [31] [33] | Local & Global [33] | Local & Global [36] |

| Key Strength | Solid theoretical foundation, consistent explanations [31] [39] | Intuitive local explanations for single instances [32] | Excellent for inspecting linear models and tree weights [31] [33] | Unified framework for model diagnostics and comparison [36] |

| Ideal For in Biology | Identifying key biomarkers from genomic data; global feature importance [40] [34] | Explaining a single prediction, e.g., why one patient was classified as high-risk [40] [31] | Debugging linear models for eQTL analysis; quick weight inspection [33] | Auditing and comparing multiple models for clinical phenotype prediction [36] |

Experimental Protocols for XAI in Biology

Protocol 1: Identifying Critical Biomarkers with SHAP

This protocol details how to use SHAP to identify the most important features (e.g., genes, SNPs) in a trained model predicting a phenotype.

- Model Training: Train your chosen classifier (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest) on your processed biological dataset (e.g., gene expression matrix).

- Explainer Initialization: Initialize the appropriate SHAP explainer. For tree-based models, use

explainer = shap.TreeExplainer(your_trained_model). - SHAP Value Calculation: Compute SHAP values for a representative subset of your data (e.g., the test set):

shap_values = explainer.shap_values(X_test). - Global Interpretation: Generate a summary plot to get a global view of feature importance and impact:

- Local Interpretation: Select a specific instance (e.g., a patient sample) and generate a force plot to explain the individual prediction:

- Biological Validation: Take the top features identified by SHAP (long bars in the summary plot) and cross-reference them with known biological pathways and literature to assess their plausibility [40] [34].

Protocol 2: Auditing and Comparing Models with DALEX

This protocol outlines the steps to audit a single model or compare multiple models using DALEX, which is crucial for ensuring model reliability before deployment.

- Model Wrapping: Create a unified explainer object for each trained model. This requires defining a predict function.

- Model Performance Check: Evaluate the model's overall performance using metrics and residual diagnostics.

- Global Feature Importance: Calculate and visualize variable importance via permutation.

- Variable Response Profiles: Create Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) or Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots to understand how a model's prediction changes with a feature.

- Model Comparison: Repeat steps 1-4 for other models you wish to compare. DALEX allows you to plot the results (e.g., feature importance, PDPs) from different models side-by-side for direct comparison [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software "reagents" essential for experiments in explainable AI for biology.

| Item (Library) | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| SHAP | Quantifies the precise contribution of each input feature (e.g., a gene's expression level) to a model's final prediction, based on a rigorous mathematical framework [40] [33]. |

| LIME | Approximates a complex model locally around a single prediction to provide an intuitive, human-readable explanation for why a specific instance was classified a certain way [40] [31]. |

| DALEX | Provides a comprehensive suite of tools for model auditing, including performance diagnosis, variable importance, and profile plots, allowing for model-agnostic comparison and validation [36]. |

| ELI5 | Inspects and debug the weights and decisions of simple models like linear regressions and decision trees, serving as a quick check during model development [31] [33]. |

| Sparse Autoencoders | A cutting-edge technique from mechanistic interpretability used to decompose the internal activations of complex models (like protein LLMs) into human-understandable features [37] [38]. |

Workflow Visualization

SHAP Local Explanation Workflow

DALEX Model Auditing Workflow

Modern genomic research increasingly relies on sophisticated computational tools and machine learning (ML) models. While these methods provide powerful predictive capabilities, they often function as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand the rationale behind their outputs. This technical support guide helps researchers navigate common issues in CRISPR off-target analysis and RNA splicing, with a special focus on interpreting results from complex algorithms and ensuring biological relevance beyond mere statistical correlations. A critical best practice is to always perform plausibility checks on ML-generated features against established scientific knowledge to avoid over-interpreting correlative findings as causal relationships [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

CRISPR Off-Target Analysis

What are the main approaches for identifying CRISPR off-target effects, and how do I choose?

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Off-Target Analysis Approaches

| Approach | Key Assays/Tools | Input Material | Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico | Cas-OFFinder, CRISPOR [42] | Genome sequence & computational models | Fast, inexpensive; useful for guide design [42] | Predictions only; lacks biological context [42] |

| Biochemical | CIRCLE-seq, CHANGE-seq, SITE-seq [42] | Purified genomic DNA | Ultra-sensitive, comprehensive, standardized workflow [42] | Uses naked DNA (no chromatin); may overestimate cleavage [42] |

| Cellular | GUIDE-seq, DISCOVER-seq, UDiTaS [42] | Living cells (edited) | Captures editing in native chromatin; reflects true cellular activity [42] | Requires efficient delivery; less sensitive; may miss rare sites [42] |

| In Situ | BLISS, END-seq [42] | Fixed cells or nuclei | Preserves genome architecture; captures breaks in native location [42] | Technically complex; lower throughput [42] |

My biochemical off-target assay identified many potential sites, but I cannot validate them in cells. Why?

This is a common issue. Biochemical methods like CIRCLE-seq and CHANGE-seq use purified genomic DNA, completely lacking the influence of chromatin structure and cellular repair mechanisms [42]. A site accessible in a test tube may be shielded within a cell. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Prioritize with Cellular Data: Use a cellular method like GUIDE-seq or DISCOVER-seq to filter your list. Sites identified by both biochemical and cellular approaches are high-priority for validation [42].

- Check Chromatin State: Cross-reference your list with histone modification data (e.g., from ENCODE). Sites in closed chromatin (heterochromatin) are less likely to be cut in cells.

- Use Multiple Methods: The FDA recommends using multiple methods, including a genome-wide approach, for a comprehensive view during pre-clinical studies [42].

The FDA has raised concerns about biased off-target assays. How should I address this?

The FDA has noted that assays relying solely on in silico predictions may have shortcomings, such as poor representation of specific population genetics [42]. Solution:

- Move to Unbiased Methods: For critical pre-clinical work, supplement your analysis with an unbiased, genome-wide assay (e.g., GUIDE-seq or CHANGE-seq) that does not depend on prior knowledge of homologous sequences [42].

- Use Relevant Cell Types: Perform off-target analysis in a cell type as physiologically similar as possible to the intended therapeutic target.

RNA Splicing Analysis

My RNA-seq splicing analysis results are highly variable across samples in the same condition. Is my experiment failing?

Not necessarily. High variability in large, heterogeneous datasets is a known challenge that can stem from biological (e.g., age, sex) or technical (e.g., sequencing batch) factors [43]. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Choose the Right Tool: Standard tools assume low variability. Use packages like MAJIQ v2, which is specifically designed for such data and includes non-parametric statistical tests (MAJIQ HET) that are more robust to heterogeneity [43].

- Check for Confounders: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize your data and identify batch effects or other confounding factors.

- Increase Sample Size: Power analysis may show that more biological replicates are needed to detect significant splicing changes above the background noise.

How can I interpret the functional impact of a differential splicing event predicted by a machine learning model?

This is a key challenge in black box ML for biology. A high-confidence prediction from a model like SpliceSeq or MAJIQ requires functional validation [44] [43]. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Inspect Protein Consequences: Use tools that map splicing events to protein domains. For example, SpliceSeq traverses splice graphs to predict alternative protein sequences and maps UniProt annotations to identify disruptions to functional elements like domains or motifs [44].

- Classify the Splicing Event: Use algorithms like the VOILA Modulizer in the MAJIQ v2 package to parse complex variations into simpler, classified types (e.g., cassette exon, intron retention), which are easier to hypothesize about functionally [43].

- Validate Experimentally: Predictions must be tested. Use RT-PCR to confirm the isoform's existence or functional assays to test the effect on the protein's activity. Remember that an ML model may identify a correlative feature that is not biologically causal [41].

I am getting inconsistent results between two popular splicing analysis tools (e.g., Cufflinks and SpliceSeq). Which one is correct?

Different algorithms use fundamentally different methodologies, leading to different results.

- Cufflinks uses a probabilistic model to assign reads to known isoforms [44].

- SpliceSeq uses splice graphs, unambiguously aligning reads to a graph of all possible exons and junctions, which can more accurately handle complex genes with many isoforms [44].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- For Complex Splicing: If your gene of interest has many densely distributed alternative events or unannotated junctions, SpliceSeq's splice graph approach may be more reliable [44].

- For Quantification: Benchmarking has shown that SpliceSeq can have a slight edge in quantitation, especially for low-frequency isoforms, which is common in heterogeneous samples like tumors [44].

- Visualize: Use each tool's visualization (e.g., VOILA v2 for MAJIQ) to manually inspect the read alignment and splicing graph for your gene of interest [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Kallisto | Ultra-fast alignment of RNA-seq reads for transcript quantification [45]. | A "pseudo-alignment" tool; extremely fast and memory-efficient, ideal for initial expression profiling [45]. |

| Bowtie | Short read aligner for mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome [44]. | Used as the core aligner in many pipelines, including SpliceSeq [44]. |

| MAJIQ v2 | Detects, quantifies, and visualizes splicing variations in large, heterogeneous RNA-seq datasets [43]. | Specifically designed for complex datasets; includes the VOILA visualizer [43]. |

| SpliceSeq | Investigates alternative splicing from RNA-Seq data using splice graphs and functional impact analysis [44] [46]. | Provides intuitive visualization of alternative splicing and its potential functional consequences [44]. |

| GUIDE-seq | Genome-wide, unbiased identification of DNA double-strand breaks in cells [42]. | Provides biologically relevant off-target data in a cellular context [42]. |

| CHANGE-seq | A highly sensitive biochemical method for genome-wide profiling of nuclease off-target activity [42]. | Requires very little input DNA and uses a tagmentation-based library prep to reduce bias [42]. |

| Limma | A popular R/Bioconductor package for differential gene expression analysis of RNA-seq data [45]. | A venerable and robust package for differential expression analysis [45]. |

Essential Experimental Workflows and Diagnostics

Workflow for Comprehensive CRISPR Off-Target Assessment

RNA-Splicing Analysis with MAJIQ v2

Diagnostic Logic for Troubleshooting Splicing Analysis

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) with RNA splicing biology is accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets, particularly in oncology. This case study details a structured platform that combines Envisagenics' SpliceCore AI engine with SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) model interpretation to identify and prioritize oncology drug targets derived from splicing errors [47]. This approach directly addresses the "black-box" problem in biological AI, creating a transparent and iterative discovery workflow.

The table below summarizes the core components of this AI-driven discovery platform:

| Platform Component | Primary Function | Key Input | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpliceCore AI Engine | Identify splicing-derived drug candidates from RNA-seq data [47] | RNA-sequencing data | A ranked list of novel target candidates |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explain AI predictions; identify influential splicing factors (SFs) [48] | SpliceCore model predictions | Interpretable insights into SF regulatory networks |

| Experimental Validation | Confirm in silico predictions via molecular biology assays [47] | AI-prioritized targets | Validated targets for therapeutic development |

The Scientific Workflow: From Data to Validated Target

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for identifying and validating a novel therapeutic target, integrating both in-silico and experimental phases.

Workflow Phase 1: AI-Driven Target Discovery with SpliceCore

The process begins with the SpliceCore platform, which uses an exon-centric approach to analyze RNA-sequencing data. Instead of analyzing ~30,000 genes, it deconstructs the transcriptome into approximately 7 million potential splicing events, creating a vastly larger search space for discovering pathogenic errors [47]. A predictive ensemble of specialized algorithms then votes on optimal drug targets based on criteria such as expression patterns, protein localization, and potential for regulator blocking. The final output of this phase is a prioritized list of candidate targets for further investigation [47].

Workflow Phase 2: Model Interpretation with SHAP

To address the "black-box" nature of complex AI models, the SHAP framework is applied. SHAP quantifies the contribution of each feature—in this context, the binding of specific Splicing Factors (SFs)—to the final model prediction for a given target [48]. This functional decomposition is a core concept of interpretable machine learning (IML) [49]. In practice, this means that for a candidate target like NEDD4L exon 13, SHAP analysis can reveal which specific SFs (e.g., SRSF1, hnRNPA1) are most influential in its mis-splicing, providing a biological narrative for the AI's prediction and informing the design of splice-switching oligonucleotides (SSOs) [48].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for the AI-Assisted Discovery Pipeline

FAQs: Computational & AI Model Issues

Q1: The SpliceCore model output lacks clarity, and the biological rationale for a top target is unclear. How can I improve interpretability?

- A: Implement SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis. SHAP provides a unified measure of feature importance and can be applied to decompose the "black-box" prediction into the contributions of individual splicing factors [48] [49]. This reveals which specific SFs and regulatory networks are likely being perturbed, adding a layer of biological transparency to the AI prediction [48].

- Recommended Action: Generate SHAP summary plots and force plots for your top target candidates. These visualizations will highlight the SFs with the greatest impact on the model's output and indicate the direction of their effect (e.g., promoting inclusion vs. skipping of an exon).

Q2: My AI model for predicting functional SSO binding sites has low accuracy. What features are most important for model training?

- A: High-performing models integrate multiple data types. One proven approach combines three key sources of splicing regulatory information [48]:

- Splicing Factor (SF) binding profiles on pre-mRNA.

- The identity of SF binding motifs.

- Probabilistic protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks within the spliceosome, which group SFs into functional clusters (SFCs) [48].

- Recommended Action: Ensure your training labels are derived from large-scale functional assays (e.g., massively parallel splicing minigene reporters). The XGboost tree model has been successfully used with these features to predict functional SSO sites with high accuracy [48].

FAQs: Experimental Validation & Troubleshooting

Q3: After transfecting TNBC cells with an AI-designed SSO targeting NEDD4L exon 13, the expected reduction in cell proliferation and migration is not observed. What should I check?

- A: This requires a systematic troubleshooting approach. First, verify that the SSO is indeed causing the intended splicing switch.

- Recommended Action:

- Confirm Splicing Modulation: Isolate RNA from treated and untreated cells and perform RT-PCR to visualize splicing changes. Confirm that the SSO is promoting the inclusion or skipping of the target exon as predicted.

- Check SSO Efficacy: Ensure the SSO was delivered efficiently and is stable within the cells. Test a range of SSO concentrations and transfection conditions.

- Verify Downstream Biology: Confirm that the splicing change leads to the expected downstream biological effect. For

NEDD4Le13, this would involve measuring activity of the TGFβ pathway via Western blot for downstream proteins like p-Smad2/3 [48]. If the pathway is not downregulated, the biological hypothesis may need refinement. - Use Appropriate Controls: Always include a scrambled-sequence control SSO to rule out non-specific effects [50].

Q4: The fluorescence signal in my immunofluorescence validation assay is dim or absent. What are the first variables to change?

- A: Always change one variable at a time to isolate the problem [50].

- Recommended Action:

- Equipment Check: Start with the simplest fix. Verify the microscope light settings and ensure the reagents have been stored correctly and are not expired [50].

- Antibody Concentration: Titrate the concentration of your primary and secondary antibodies. The most common issue is using an antibody concentration that is too low [50].

- Fixation and Permeabilization: If antibody titration fails, optimize the fixation time and permeabilization conditions. Under-fixation or inadequate permeabilization can result in poor antibody access to the target.