GPS Telemetry Tags in Animal Movement Research: From Foundational Technology to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of GPS telemetry tags for animal movement tracking, tailored for researchers and scientists.

GPS Telemetry Tags in Animal Movement Research: From Foundational Technology to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of GPS telemetry tags for animal movement tracking, tailored for researchers and scientists. It explores the technological evolution from basic tracking to sophisticated, miniaturized transmitters and global satellite networks. The scope covers foundational principles, innovative methodological applications across diverse species, critical analytical frameworks for data interpretation, and comparative validation of tracking methodologies. Special emphasis is placed on how these technologies enable groundbreaking ecological insights and create novel opportunities for biomedical research, including disease vector tracking and behavioral pharmacology models.

The Evolution of Animal Tracking: From GPS Origins to Global Satellite Networks

The expansion of global satellite constellations to over 9,000 active satellites represents a transformative infrastructure for wildlife research, enabling near real-time tracking of animal movements across even the most remote ecosystems [1]. This connectivity backbone supports advanced GPS telemetry tags that transmit finely resolved location data to researchers worldwide, overcoming the historical limitations of data retrieval from inaccessible locations [1]. Modern satellite systems, including established networks like Argos and GPS, alongside emerging constellations from companies like Kinéis and Talos, provide the essential communication link between animal-borne sensors and research institutions [1] [2]. This technological evolution supports a paradigm shift in movement ecology, allowing scientists to monitor animal response to environmental change at unprecedented spatial and temporal scales, which is critical for understanding biodiversity loss, climate change impacts, and disease spread [2].

Satellite Systems and Services: A Comparative Analysis

2.1 Core Satellite Systems Wildlife telemetry utilizes multiple satellite systems, each with distinct operational principles and technological strengths. The Argos system, established in 1978 and operated through collaboration between the French Space Agency, NOAA, and NASA, calculates animal locations using the Doppler effect on signals received by polar-orbiting satellites [3] [4]. The GPS constellation, operated by the U.S. Space Force, comprises 31 satellites that enable tags to compute highly precise location fixes [4]. Emerging systems like Kinéis, a spin-off from the French Space Agency, are deploying a new generation of 25 nanosatellites designed specifically for Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity, offering low-cost, low-energy data transmission from remote areas [1]. The ICARUS 2.0 initiative (a partnership between startup Talos and the Max Planck Society) plans a dedicated cubesat constellation of at least five satellites for high-precision animal tracking, demonstrating the trend toward specialized conservation constellations [2].

2.2 System Performance Characteristics The performance characteristics of satellite systems directly influence research design and data quality. The following table summarizes key operational parameters for major systems used in wildlife tracking:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Satellite Systems Used in Wildlife Telemetry

| System | Location Calculation Method | Typical Location Accuracy | Coverage | Primary Data Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argos | Doppler effect on uplink signals [3] | 250 meters to 4 kilometers [3] [5] | Global, with better coverage at higher latitudes [3] | Long-distance migration, marine species tracking [5] |

| GPS | Satellite trilateration by tag [3] [4] | 5-10 meters (can be centimeter-level with augmentation) [6] | Global [4] | Fine-scale movement ecology, habitat use studies [7] |

| GPS/Satellite Hybrid | GPS calculation with satellite data transmission [3] | 5-10 meters (inherited from GPS) [3] | Global | Near real-time tracking with high precision [3] |

Table 2: Data Transmission Capabilities of Satellite Systems

| System/Technology | Data Transmission Method | Update Frequency | Tag Power Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argos | Tag transmits to satellite; satellite transmits to ground [3] [4] | 6-28 passes per day depending on latitude [3] | Moderate (transmitter only) |

| GPS Satellite Transmit | Tag transmits stored GPS data via Argos or Iridium [3] | User-programmable (e.g., daily) [5] | High (GPS receiver + transmitter) |

| Iridium | Two-way satellite communication [1] | Higher potential frequency | Higher (two-way communication) |

| Kinéis (Emerging) | Low-power, low-cost satellite uplink [1] | Several times daily [1] | Low (designed for IoT) |

Experimental Protocols for Satellite-Based Wildlife Tracking

3.1 Protocol 1: Tag Selection and Deployment Objective: Select and deploy an appropriate satellite tag to minimize animal impact while achieving research data goals. Materials: Satellite tag, species-appropriate attachment kit (harness, collar, glue, etc.), animal capture and handling equipment, telemetry receiver for tag recovery (optional). Methodology:

- Tag Selection: Choose tag based on animal species, mass, and research questions. Tags must typically be <5% of animal body mass [8]. Key considerations:

- SPOT Tags: For marine animals spending time at surface (sharks, sea turtles, pinnipeds); transmit locations to Argos system when tag is exposed to air [5].

- GPS/Satellite Hybrid Tags: For high-precision tracking of terrestrial species; record GPS locations and transmit via satellite [3].

- Archival Tags: For species where recapture is feasible; store data internally for later retrieval [4].

- Programming: Configure data collection and transmission schedules prior to deployment via manufacturer software (e.g., Wildlife Computers Tag Portal) [5]. Prioritize data transmission to extend battery life for specific seasons or satellite pass times.

- Attachment: Safely capture animal and attach tag using species-appropriate method. Common techniques:

- Release and Monitoring: Release animal and initiate data acquisition via satellite data portal (e.g., Wildlife Computers Data Portal, Argos system) [5].

3.2 Protocol 2: Data Acquisition and Processing Workflow Objective: Establish robust pipeline for acquiring, processing, and validating satellite-derived animal location data. Materials: Computer with internet access, access to relevant data portals (Argos, Wildlife Computers, etc.), data processing software (R, Python, GIS). Methodology:

- Data Reception: Raw location data is automatically delivered from satellite processing centers (e.g., Argos centers in Toulouse, France and Landover, Maryland, USA) to researcher accounts [3].

- Data Filtering: Implement quality control filters to remove erroneous locations using:

- Location Class Filtering: Argos data provides location quality classes (e.g., LC 3,2,1,0,A,B,Z) with estimated accuracy [5].

- Velocity Filters: Remove locations requiring unrealistic movement speeds.

- Spatial Filters: Remove locations outside feasible habitat (e.g., terrestrial points for marine species).

- Data Augmentation: Enhance location data with supplemental sensor information (temperature, depth, acceleration, humidity) collected by modern tags [5] [2].

- Data Integration: Merge telemetry data with environmental layers (sea surface temperature, primary productivity, land cover) in GIS for analysis.

3.3 Protocol 3: System Performance Validation Objective: Field-validate accuracy and reliability of satellite telemetry system. Materials: Test tag, GPS receiver with known high accuracy, open area with clear sky view, data analysis software. Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: Place test tag at known locations surveyed with high-precision GPS.

- Data Collection: Collect satellite-derived locations over extended period (e.g., 2-4 weeks) under varying environmental conditions.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare satellite-derived locations to known coordinates to quantify:

- Positional Accuracy: Mean and variance of location error.

- Fix Success Rate: Percentage of successful location attempts versus scheduled attempts.

- Environmental Effects: Document effects of habitat, topography, and weather on performance.

- Battery Life Validation: Monitor power consumption against manufacturer specifications under actual transmission patterns.

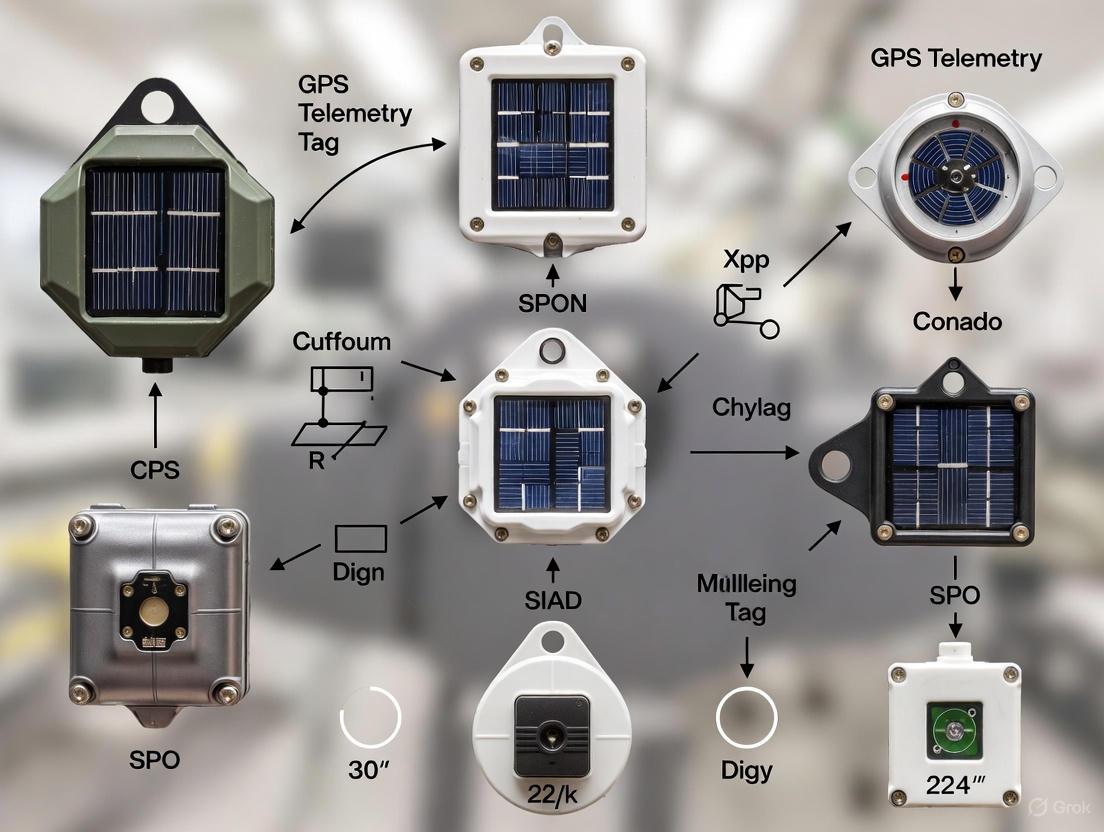

The following diagram illustrates the complete data flow from animal-borne tag to researcher, highlighting the roles of different satellite constellations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of satellite telemetry requires specialized equipment and software tools. The following table details essential components of the modern wildlife tracking toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Materials for Satellite-Based Wildlife Tracking Research

| Item | Function | Example Specifications/Models |

|---|---|---|

| Satellite Transmitter Tags | Collect and transmit animal location and sensor data via satellite systems. | SPOT tags (Argos transmission) [5], GPS/Satellite hybrid tags [3], ICARUS tags (5g with sensors) [2] |

| Attachment Systems | Securely affix tags to study animals with minimal impact. | Custom-designed collars [7], backpack harnesses [4], fin mounts, transdermal anchors [5] |

| Data Portal Access | Receive, process, manage, and visualize transmitted telemetry data. | Wildlife Computers Data Portal [5], Argos Web Service, Movebank data management platform |

| Programming Interfaces | Configure tag parameters (sampling schedules, transmission priorities). | Wildlife Computers Tag Portal [5], Manufacturer-specific software suites |

| Field Recovery Equipment | Locate and retrieve tags with archival data or for redeployment. | VHF receivers and directional antennas (often integrated into GPS tags) [8] |

| Sensor Modules | Measure environmental and physiological variables. | Temperature sensors, accelerometers, wet/dry sensors, pressure/depth sensors [5] [2] |

| Validation Equipment | Assess system performance and tag accuracy. | High-precision GPS receivers, test stations, calibration tools |

The infrastructure of over 9,000 satellites enables a new era of global connectivity for wildlife tracking, transforming how researchers study animal movement across the planet. By leveraging constellations including GPS, Argos, and emerging systems from Kinéis and ICARUS 2.0, scientists can gather high-resolution movement data in near real-time from virtually any location on Earth. The experimental protocols and toolkit resources detailed in this document provide a framework for implementing robust satellite telemetry studies. As satellite technology continues to evolve toward smaller tags, enhanced sensor capabilities, and dedicated conservation constellations, researchers will gain unprecedented insights into animal behavior, species responses to environmental change, and the ecological connectivity of global ecosystems.

Global Positioning System (GPS) telemetry has revolutionized animal movement tracking research, enabling scientists to remotely monitor the location, behavior, and environmental interactions of wildlife across the globe. These systems provide critical insights into migration patterns, habitat use, and ecological processes, supporting conservation efforts and ecological research [9] [10]. A comprehensive understanding of the core components of these systems—transmitters, networks, and data platforms—is essential for researchers designing tracking studies and interpreting the resulting data. This document details the technical specifications, operational protocols, and system architectures that constitute modern GPS telemetry infrastructure for wildlife research.

Core Components and System Architecture

A GPS telemetry system functions as an integrated technological suite designed to collect, transmit, process, and visualize animal location data. The system's architecture comprises three fundamental subsystems: the transmitter (animal-borne device), the communication network (data transmission pathway), and the data platform (data management and analysis interface). The logical flow of information through these components is illustrated below.

This dataflow is foundational to all GPS telemetry applications. The animal-borne transmitter acquires location coordinates from GPS satellites. This data is then relayed via a communication network to a central data platform, where it is processed, stored, and made accessible to researchers for analysis [11] [9] [12]. In advanced systems, a two-way communication link allows researchers to remotely modify transmitter parameters, such as the frequency of location fixes, based on initial findings or animal behavior [12].

Transmitter Components and Specifications

The transmitter, or tag, is the primary data collection unit deployed on the animal. Its design involves critical trade-offs between device weight, battery longevity, data resolution, and functionality.

Internal Components and Specifications

Modern transmitters integrate several key components into a single, ruggedized package:

- GPS Receiver: Acquires location fixes from satellite constellations. Performance is measured by metrics like Time to First Fix (TTFF), which can be improved with technologies like Quick Fix Pseudoranging (QFP) to as little as 2-5 seconds, conserving battery life [12].

- Battery: The primary constraint on device longevity. Solar panels are increasingly integrated to extend operational life [13]. Battery capacity must be balanced against device weight, especially for small species [14].

- Sensors: Beyond location, modern tags can include tri-axial accelerometers, temperature sensors, magnetometers, and wet/dry sensors, providing rich data on animal behavior and environment [10] [12].

- Memory: Onboard non-volatile flash memory stores sensor data pending transmission. Capacities can exceed 500,000 location fixes [12].

- Communication Module: The hardware (e.g., Iridium, GSM, or Argos modem) that transmits data via the chosen network [9] [12].

Device Types and Comparative Performance

Different research objectives and animal species necessitate different transmitter types. The following table summarizes the primary technologies, their performance characteristics, and ideal use cases.

Table 1: Comparison of Wildlife Tracking Device Technologies

| Device Type | Typical Weight | Location Accuracy | Data Retrieval | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS with Satellite Uplink (e.g., Iridium) | > 5g [12] | ~2-5m [12] | Remote, global via satellite | Real-time data, global coverage, two-way communication | Heavier, higher cost, requires data plan [12] | Large mammals, long-distance migrants, remote areas |

| GPS with GSM Uplink | Varies | ~2-5m | Remote, via cellular networks | Lower operational cost, high data resolution | Requires cellular coverage [9] | Studies in areas with reliable cell service |

| Platform Transmitter Terminal (PTT) | ~2g and up [14] | ~100-1000m | Remote, via Argos satellite system | Lighter weight, smaller size, global coverage | Lower spatial accuracy, less frequent data [14] | Small to medium birds, long-distance migration studies |

| GPS Data Loggers | < 5g [14] | ~2-5m | Physical recovery of device | Lightest weight, highest accuracy for size, no data plan | Requires recapturing the animal [14] | Small species where recapture is feasible |

| Radio Telemetry | < 5g [14] | Varies with proximity | Manual tracking with receiver | Lightweight, inexpensive, long battery life | Labor-intensive, limited to local scales, no remote data [14] | Small-scale studies, locating nests or dens |

The choice of transmitter is often dictated by the 3-5% rule, which states that the device's weight should not exceed 3-5% of the animal's body mass to minimize impact on its natural behavior [14]. A study comparing GPS collars and solar-powered GPS ear tags on beef cows found significant differences in performance: collars had a mean horizontal error of 2m and 100% fix acquisition, while ear tags had 41m error and only 30.7% fix acquisition during animal testing, the latter driven largely by battery life issues [13].

Communication Networks and Data Retrieval

The communication network is the critical link between the field-based transmitter and the researcher. The selection of a network is a strategic decision based on the study's geographical scope, required data latency, and budget.

Table 2: Comparison of Data Communication Networks for Wildlife Telemetry

| Network Type | Coverage | Data Latency | Bandwidth | Two-Way Communication | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite (Iridium) | Global [12] | Hours to days [12] | Medium (~70-80 fixes/message) [12] | Yes [12] | High [12] |

| Satellite (Argos) | Global [9] | Days | Low | Limited | High |

| GSM/Cellular | Regional [9] | Near real-time [9] | High | Yes | Low [9] |

| Radio (VHF/UHF) | Local (line-of-sight) | N/A (manual download) | High only upon recovery | No | Low [9] |

| Sigfox/LoRa | Expanding remote areas [9] | Low to moderate | Low | Yes | Low to Moderate [9] |

- Iridium Satellite Network: A system of 66 cross-linked low-earth orbit satellites providing continuous global coverage. Its two-way communication capability allows for confirmation of data receipt and remote reprogramming of field devices, a significant advantage for long-term studies [12].

- Argos System: A scientific satellite system operational since 1978, often used with Platform Transmitter Terminals (PTTs). It is well-suited for tracking long-distance migrations of lighter species, though with lower spatial accuracy than GPS [9] [14].

- GSM/Cellular Networks: Utilize existing mobile phone infrastructure to transmit data via SMS or internet protocols (GPRS). This is a cost-effective solution but is limited to areas with reliable cellular coverage [9].

- Hybrid Systems: Many modern transmitters incorporate multiple technologies. For example, a device may use Iridium for primary data transfer but also include a VHF transmitter to aid in the final physical recovery of the animal or the unit itself [12].

Data Platforms and Analytical Frameworks

Once transmitted, data is processed, stored, and analyzed through specialized software platforms. These platforms transform raw data streams into actionable biological insights.

Core Platform Functions

- Data Processing and Management: Raw data from transmitters is decoded, filtered for erroneous fixes, and formatted. Platforms like Movebank, which holds over seven billion sensor records across 1,400 species, serve as massive, centralized repositories for wildlife tracking data [10].

- Visualization and Analysis: Geographic Information System (GIS) software and custom tools (e.g., GRASS, Google Earth) allow researchers to plot animal movements on maps, calculate home ranges, and identify movement corridors [9].

- Integration with Environmental Data: A key advancement of platforms like the Internet of Animals is the integration of animal movement data with satellite-derived environmental data, such as vegetation changes, surface water depth, and land use. This enables researchers to understand why animals move in response to environmental conditions [10].

- Predictive Modeling: Combined telemetry and environmental data feed into statistical models in platforms like R, allowing scientists to predict animal distribution under future climate scenarios or assess disease transmission risks, such as avian influenza spread by waterfowl [9] [10].

The workflow for handling data from acquisition to publication is methodical and iterative, as shown in the following protocol.

Experimental Protocols for System Deployment

A successful GPS telemetry study requires meticulous planning and execution across three phases: pre-deployment, field deployment, and post-deployment data management.

Pre-Deployment Planning and Device Configuration

Objective: To define research questions and select/configure appropriate technology. Protocol:

- Define Biological Questions: Clearly articulate the study's goals (e.g., "Determine the migration routes and stopover sites of the Eastern Curlew.").

- Select and Configure Transmitters:

- Choose device type and attachment method based on species morphology and behavior (see Table 1).

- Use manufacturer software (e.g., Telonics Product Programmer - TPP) to program duty cycles. Balance fix frequency (e.g., 4-8 fixes/day for migration studies) against battery life estimates [12].

- For testing, configure geofencing alerts to notify researchers if an animal enters or leaves a predefined area [12].

- Ethical and Welfare Review: Secure approval from institutional animal care and use committees. Adhere to the 3-5% body weight rule for device mass [14].

Field Deployment and Animal Tagging

Objective: To safely capture animals and deploy transmitters with minimal impact. Protocol:

- Capture: Use species-appropriate, safe capture techniques (e.g., mist nets for birds, cage traps for mammals) by trained personnel.

- Attachment:

- Collars: Used for mammals where the head is larger than the neck (e.g., primates, large cats) [9].

- Harnesses: Used for animals where neck diameter exceeds head size (e.g., pigs, Tasmanian devils) or for large birds [9].

- Leg-loop Harnesses: For shorebirds, use soft, degradable materials (e.g., elastic) to minimize long-term impacts [14].

- Direct Attachment: For birds, reptiles, and marine mammals, devices are glued to feathers, skin, or carapace, and are designed to fall off during molting [9].

- Data Verification: Before release, confirm the device is powered on and has acquired a GPS fix.

Post-Deployment Data Management and Analysis

Objective: To process, analyze, and interpret transmitted data. Protocol:

- Data Retrieval: Automate data flow from the communication network (e.g., Iridium) to a designated data platform (e.g., Movebank) [10] [12].

- Data Cleaning: Filter location data based on dilution of precision (DOP) values, fix dimensions (2D/3D), and movement speed to remove implausible locations.

- Data Analysis:

- Use GIS software to visualize movement paths and calculate metrics like daily distance traveled and home range size (e.g., using kernel density estimation) [9].

- Apply movement models (e.g., in R package

moveHMM) to identify behavioral states (e.g., foraging, migrating, resting) from GPS and accelerometer data [9] [10]. - Integrate location data with remote sensing layers (e.g., NDVI for vegetation, land cover class) to assess habitat selection [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and software solutions essential for conducting GPS telemetry research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for GPS Telemetry Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GPS/Iridium Transmitter | Collects and remotely transmits high-resolution location data globally. | E.g., Telonics TGAV-4270-5: Weight: 140g, Memory: ~500K fixes, Iridium two-way communication for remote programming [12]. |

| Platform Transmitter Terminal (PTT) | Tracks long-distance migration of smaller species via Doppler shift. | Weight: ~2-5g, Uses Argos satellite system, lower spatial accuracy than GPS, suitable for birds under 200g [14]. |

| GPS Data Logger | Stores high-accuracy location data internally for later retrieval. | Weight: <5g, No data transmission cost, requires animal recapture, highest accuracy-to-weight ratio [14]. |

| VHF Transmitter & Receiver | Enables short-range, ground-based tracking and device recovery. | Used as a backup to satellite systems; essential for locating animals in dense habitat or recovering data loggers [12]. |

| Attachment Materials | Secures the transmitter to the animal with minimal welfare impact. | Includes collar material, harnesses (e.g., leg-loop made from degradable elastic), and non-toxic epoxy for direct attachment [9] [14]. |

| Movebank Platform | A free online platform for managing, sharing, analyzing, and archiving animal movement data. | Hosts billions of data points; allows integration with environmental data from NASA and other remote sensing sources [10]. |

| Telonics Product Programmer (TPP) | Software for programming, estimating battery life, and sending remote commands to compatible transmitters. | Allows customization of GPS fix schedules, VHF pulses, and Iridium transmission intervals [12]. |

| R Statistical Software | Open-source platform for statistical computing and graphics, essential for advanced movement analysis. | Used with specialized packages (e.g., move, amt, moveHMM) for analyzing trajectories, habitat selection, and behavioral states [9]. |

Application Notes

The development and deployment of the BlūMorpho transmitter, a 60-milligram, solar-powered radio tag, represents a pivotal advancement in wildlife telemetry [15] [16]. This miniaturization breakthrough enables high-resolution tracking of small, migratory insects like the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), a species previously unsuitable for individual long-distance telemetry studies due to its low body mass (typically under a gram) [15].

The technology's application within Project Monarch, a large-scale collaborative effort, has successfully provided the first near-real-time, individual-level data on the complete monarch migration from Canada to their overwintering sites in central Mexico [15] [17]. The transmitters operate at 2.4 GHz (Bluetooth frequency), allowing their signals to be detected not only by dedicated wildlife receiver networks (e.g., Motus) but also by millions of standard smartphones running the dedicated Project Monarch app, creating a massive, crowd-sourced detection network [15] [16].

Table 1: Key Performance Data from the 2025 Project Monarch Tracking Season

| Metric | Value | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Transmitter Mass | 60 mg | Ultralight, solar-powered [15] [16] |

| Total Transmitters Deployed | >400 | Deployed across North America and the Caribbean [15] |

| Partner Organizations | >20 | Cross-institutional collaboration [15] [17] |

| Sample Success Rate (Monarch Watch) | 30% (9 of 30) | Proportion of tagged monarchs detected in Mexico [17] |

| Detection Range Enhancement | Continental scale | Leveraged dedicated receivers and crowd-sourced smartphone networks [15] |

Research Context and Significance

This technology directly addresses a core limitation in movement ecology: obtaining high-resolution spatiotemporal data from small-bodied animals [18]. Prior to this, monarch migration studies relied on mark-recapture using physical sticker tags, which provide only two data points—release and (if fortunate) recovery [17]. The BlūMorpho transmitter reveals the entire journey, capturing fine-scale movements, routes, stopovers, and responses to environmental conditions like wind, as demonstrated by the detailed track of monarch "MW026" [17].

The data fidelity is sufficient to observe that migration progress can be significantly slowed by unfavorable southern winds, a level of ecological insight previously unattainable [17]. Preliminary results from the 2025 season suggest that the success rate of tagged monarchs reaching Mexico may exceed previous population-level estimates, opening new avenues for researching migration survivorship [17].

Experimental Protocols

The following protocol outlines the methodology for deploying BlūMorpho transmitters and collecting tracking data, as utilized by the Project Monarch collaboration in the fall 2025 season [15] [17].

Pre-Deployment: Transmitter Activation and Ethical Considerations

- Transmitter Check: Verify that the BlūMorpho transmitter is functional and charging via its integrated solar panel under light exposure [15].

- Ethical Review and Permitting: Secure all necessary permits from relevant wildlife and conservation authorities for the capture, handling, and tagging of monarch butterflies [19]. The project adhered to standardized protocols reviewed by collaborating institutions [15].

- Animal Welfare Assessment: Prior to deployment, researchers should justify that the scientific objectives outweigh the potential impact on the individual. Research from James Madison University integrated into the project concluded that survival was unlikely to be impacted in properly tagged individuals [15].

Field Deployment: Capture and Tagging

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function | Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BlūMorpho Transmitter | Emits a unique RF signal for individual identification | 60 mg, 2.4 GHz, solar-powered [15] [16] |

| Adhesive | Affixes transmitter to the butterfly | Hypo-allergenic, non-toxic, quick-setting formula |

| Fine-point Forceps | For precise handling during tag attachment | - |

| Butterfly Net | For safe capture of wild monarchs | - |

| Project Monarch App | Installed on smartphone to act as a passive receiver | Available on iOS and Android [15] |

- Capture: Using a butterfly net, safely capture a wild, migrating monarch butterfly.

- Handling: Gently handle the butterfly to minimize stress. The species is resilient to brief handling periods.

- Tag Attachment: Using fine-point forceps, apply a small, minimal amount of safe adhesive to the base of the transmitter. Carefully affix the transmitter to the butterfly's dorsal thorax, ensuring the solar panel is unobstructed and the insect's movement is not impeded. The entire attachment process should be completed in under two minutes.

- Release: Release the tagged monarch at the site of capture and record the precise release coordinates, date, and time.

Data Collection and Processing Workflow

The data collection leverages a multi-modal network, and the subsequent processing converts raw signals into reliable location estimates. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: Workflow for wildlife tracking data acquisition and processing.

- Signal Detection: The transmitter's signal is passively detected by a network of receivers [15]. This network includes:

- Data Transmission: Raw detection data, including Received Signal Strength (RSS), timestamp, and transmitter ID, are uploaded to a central data portal (e.g., the BlūMorpho Portal) [15].

- Location Estimation: A grid search algorithm is recommended for converting RSS data into accurate location estimates [18]. This method involves:

- Model Fitting: Prior to analysis, an exponentially decaying function (S(d) = A - B exp(-C d)) is fitted to empirical data characterizing the relationship between RSS and distance for the specific transmitter-receiver system [18].

- Grid Calculation: The study area is divided into a fine-scale grid. For each grid cell, the algorithm calculates the distance to every receiver that detected the signal [18].

- Likelihood Scoring: A criterion function (e.g., a normalized sum of squared differences) compares the measured RSS values from all receivers with the values predicted by the RSS-distance model for that grid cell. The cell with the lowest score (best fit) is the most likely location of the transmitter [18]. This method has been shown to be more than twice as accurate as traditional multilateration, especially in receiver networks with wide spacing [18].

- Data Cleaning and Error Checking: Implement an automated data cleaning pipeline to identify and flag biologically implausible locations resulting from signal noise or other errors [20] [21]. This involves:

- Analysis and Visualization: The cleaned, high-resolution tracking data can be analyzed for movement metrics (speed, direction, stopover duration) and visualized in the Project Monarch Science app or other GIS software to reveal migration paths and individual behaviors [15] [17].

The study of animal movement has been revolutionized by advances in GPS telemetry and biologging, enabling researchers to track everything from livestock to elusive wildlife across the globe. These technologies provide critical data on migration, behavior, and habitat use, which directly informs conservation strategies, livestock management, and ecological research.

Selecting the appropriate tracking device is a critical decision that balances research objectives, species-specific constraints, and technological capabilities. The fundamental principle is that the device should not harm the animal or alter its natural behavior; for birds, a device should typically not exceed 3-5% of the animal's body weight [14]. This guide details the diverse tag types available, their applications, and standardized protocols for their use in scientific research.

Tag Type Comparison and Selection

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the primary electronic tracking devices used in animal movement research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Animal-Borne Tracking Devices

| Tag Type | Typical Weight Range | Key Technologies | Spatial Accuracy | Data Access Method | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS Ear Tag | >10g [13] | GPS, Cellular/Satellite | ~41m to ~59m [13] | Remote (GSM/Satellite) | Livestock management, wildlife tracking [22] |

| GPS Collar | >10g [13] | GPS, Argos, UHF | ~2m [13] | Remote (GSM/Satellite) or Direct | Large mammal tracking, ecology studies [23] |

| Platform Terminal Transmitter (PTT) | ~2g and above [14] | Doppler Shift, Argos | 150m - 5000m [14] | Remote (Satellite) | Long-distance migration of birds [14] |

| Radio Transmitter | <5g [14] | VHF Radio | Limited to receiver range | Direct (Manual Tracking) | Small-scale movement studies [14] |

| Geolocator | <5g [14] | Light-level Sensors | ~200km [14] | Direct (Device Recovery) | Approximate migratory pathways [14] |

| Marine Tag (e.g., SPOT/SPLASH) | Varies (deployed on marine mammals) [24] | Argos, Fastloc GPS | Varies (GPS is more accurate) [24] | Remote (Satellite) | Marine mammal movement & dive behavior [24] |

Selection Workflow Logic

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate animal tracking tag based on research priorities and species constraints.

Experimental Protocols for Deployment

Adhering to standardized protocols ensures the scientific rigor of tracking studies and prioritizes animal welfare.

Protocol: Deploying GPS Ear Tags on Livestock

Objective: To securely attach a GPS ear tag for monitoring location, herd movement, and health metrics in a ranch setting [22].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GPS Ear Tag Deployment

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Solar-Powered GPS Ear Tag | Tracking device; solar power extends battery longevity for long-term studies [13]. |

| Livestock Restraint Chute | Safely and humanely immobilizes the animal during the tagging procedure. |

| Disinfectant Wipes/Swabs | Cleans the ear pre-deployment to minimize infection risk (e.g., 70% isopropyl alcohol). |

| Applicator Tool | Specialized tool designed for the specific tag model to ensure correct and secure application. |

| Data Logging Software/Dashboard | Platform (e.g., proprietary cloud software) to receive, visualize, and analyze transmitted GPS data [25]. |

Methodology:

- Animal Restraint: Guide the animal into a restraint chute to minimize stress and ensure handler safety.

- Site Preparation: Identify the tagging site (typically the center of the ear). Remove dirt and debris, then thoroughly disinfect the area.

- Tag Application: Load the tag into the applicator tool. Position the applicator precisely on the marked site and deploy in a single, swift motion to ensure a clean penetration.

- Post-Application Check: Verify the tag is seated correctly and not overly tight. Apply a topical antiseptic to the wound site if necessary.

- Data Verification: Release the animal and confirm the tag is transmitting location data successfully to the online dashboard or software platform [25].

Protocol: Fitting a GPS Collar on a Large Terrestrial Mammal

Objective: To deploy a GPS collar on a large mammal (e.g., wolf, deer) to collect high-accuracy movement data and study home range, habitat use, and behavior [23].

Methodology:

- Animal Capture: A trained veterinarian or wildlife biologist must perform the capture using safe and approved methods (e.g., chemical immobilization via darting).

- Animal Welfare Monitoring: Continuously monitor the animal's vital signs (heart rate, respiration, body temperature) throughout the procedure.

- Collar Fitting: Place the collar around the animal's neck. Ensure you can fit two fingers between the collar and the neck to prevent injury or choking as the animal grows or seasons change.

- Data Logger Programming: Configure the GPS collar's settings (e.g., fix schedule, data transmission interval) according to the research plan before release.

- Release and Monitoring: Administer antagonists to reverse immobilization drugs in a safe, controlled manner. Monitor the animal until it fully recovers and ambulates normally.

Protocol: Deploying a PTT on a Migratory Shorebird

Objective: To track the long-distance migration of a small to medium-sized shorebird using a lightweight Platform Terminal Transmitter (PTT) [14].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Shorebird PTT Deployment

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Platform Terminal Transmitter (PTT) | Miniaturized satellite transmitter; weight must be <2-3g for small shorebirds [14]. |

| Leg-Loop Harness | Attachment system made of soft, degradable material (e.g., elastic) to minimize long-term impact [14]. |

| Field Scales | Precision scales (e.g., 0.1g accuracy) to weigh the bird and ensure the device is <5% of body mass. |

| Argos Satellite System | Satellite network used to receive transmissions from the PTT and calculate location estimates [14]. |

Methodology:

- Capture and Processing: Capture the bird using a mist net. Weigh and record morphological measurements.

- Harness Fitting: Carefully thread the bird's legs through the pre-fashioned leg loops of the harness. Adjust the harness to fit snugly but without restricting movement.

- Attachment: Secure the PTT to the harness on the bird's back. Verify the fit does not interfere with flight, feeding, or preening.

- Release: Release the bird at the capture site and observe initial flight behavior.

- Data Acquisition: Locations are calculated via the Argos satellite system based on Doppler shift, with accuracy varying from 150m to several kilometers [14].

Technological Foundations and Data Processing

Understanding the underlying technology is crucial for data interpretation and system design.

Core Tracking Technologies and Data Flow

The diagram below illustrates the core technologies and signaling pathways involved in modern wildlife tracking systems.

Protocol: Improving Spatial Accuracy in Radio Telemetry

Objective: To enhance the accuracy of location estimates in an Automated Radio Telemetry System (ARTS) using a grid search algorithm instead of traditional multilateration [18].

Methodology:

- System Setup: Establish a network of fixed radio receivers with overlapping detection ranges within the study area.

- Signal Strength Modeling: Fit an exponentially decaying function (S(d) = A - B exp(-C d)) to characterize the relationship between Received Signal Strength (RSS) and distance using calibration data from known locations [18].

- Data Collection: Record the RSS of a target animal's transmitter at multiple synchronized receivers.

- Grid Search Execution:

- Superimpose a fine-scale grid over the study area.

- For each grid cell, calculate the distance to every receiver that detected the signal.

- Compute a likelihood score (e.g., χ²) comparing the observed RSS values with the model-predicted values for that cell [18].

- Location Estimation: Identify the grid cell with the lowest χ² value, which represents the most probable location of the animal. This method has been shown to be more than twice as accurate as multilateration in experimental conditions [18].

Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

The proliferation of biologging devices necessitates rigorous ethical review. Evidence suggests a significant proportion of tracking projects fail to generate published scientific knowledge, potentially trivializing this invasive technology [19].

Researchers must justify projects with clear objectives, explore non-invasive alternatives, and use the minimum sample size required for robust results, adhering to the "Replace, Reduce, Refine" framework [19]. Regulations must ensure that the welfare of the studied individuals is paramount and that the data collected culminates in tangible conservation or scientific outcomes [19].

Advanced Applications and Deployment Strategies in Contemporary Research

The use of Global Positioning System (GPS) telemetry tags has revolutionized animal movement tracking research, enabling unprecedented insights into the ecology and behavior of diverse species. This capability carries a significant ethical responsibility to minimize harm and disturbance to the studied animals. Adherence to species-specific protocols is not merely a methodological preference but a fundamental component of ethical research and conservation practice. These protocols ensure that the data collected accurately reflect natural behaviors and that the welfare of individual animals and their populations is safeguarded.

The core ethical framework for biologging is guided by the Three Rs principle: Reduction, Refinement, and Replacement [26]. Researchers must justify that the number of animals tagged (Reduction) is the minimum necessary for robust scientific inference, refine tagging methods and device designs to minimize animal welfare impacts (Refinement), and consider alternative, less invasive methods where possible (Replacement). A growing body of evidence indicates that tracking devices can have measurable effects on animal behavior, reproduction, and survival [27]. Therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach is ethically and scientifically untenable; protocols must be tailored to the specific morphology, ecology, and physiology of the target species.

Pre-Deployment Planning and Justification

Experimental Justification and Objective Setting

Prior to any animal capture or device deployment, researchers must clearly define the scientific and conservation objectives. The research questions should be of sufficient importance to justify the potential disturbance and risk associated with tagging. GPS technology is particularly powerful for addressing questions related to fine-scale resource selection, migration ecology, and human-wildlife conflict [28]. The study design must also account for the high cost of GPS units, which often forces a trade-off between collar capabilities and sample size, potentially weakening population-level inference [28]. A power analysis should be conducted to determine the minimum sample size required to achieve the stated objectives, ensuring that the study is scientifically valid and that the use of animals is justified.

Animal Welfare Risk Assessment

A comprehensive risk assessment is a critical precursor to any tagging operation. This assessment should consider:

- Capture and Handling: The stress and risk associated with capture, restraint, and sedation.

- Device Impact: The potential for the device to cause increased energy expenditure, changes in behavior, injury, or elevated predation risk.

- Device Mass and Design: The device's mass, shape, aerodynamics, and hydrodynamics must be evaluated for the specific species. The traditional guideline that a device should be less than 2-5% of the animal's body weight is a common but debated starting point; one analysis of bird studies found that tagging produced small but significant impacts on survival and reproduction [27]. Physical modeling of how a tag might affect an animal's movement (e.g., flight, climbing, or running) is a recommended practice for predicting and mitigating impacts [27].

Table 1: Key Considerations in Pre-Deployment Ethical Review

| Consideration | Description | Ethical Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Merit | Are the research questions clearly defined and can they justify the potential impact on the animal? | Reduction |

| Species Suitability | Is the target species appropriate for tagging given its conservation status, life history, and morphology? | Replacement |

| Device Selection | Has the smallest, lightest, and most streamlined device been selected for the research objectives? | Refinement |

| Sample Size | Has a power analysis been conducted to use the minimum number of animals for robust inference? | Reduction |

| Permitting | Have all required approvals from institutional, governmental, and journal ethics boards been obtained? | N/A |

Species-Specific Protocol Development

Device Selection and Customization

Choosing the appropriate tag type is a critical species-specific decision. For marine animals, options range from transmitting tags that send data via satellites like Argos for wide-ranging species, to pop-up archival tags (PATs) that record data and then release to transmit [29]. For pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), a key distinction is made between externally attached telemetry devices (ETDs) and fully implanted devices, with ETDs being less invasive but having limited retention times [26].

The attachment method must be customized to the species. For pinnipeds, common attachments include glue, epoxy, or harnesses, each with different trade-offs regarding retention, hydrodynamic profile, and potential for injury [26]. Device deployment duration should be planned to answer the scientific question while minimizing the time the animal carries the device. For long-term studies, researchers should consider deploying tags with a automatic release mechanism to avoid the device becoming a permanent fixture or requiring recapture for removal.

Capture, Handling, and Attachment Procedures

Standardized operating procedures for capture and handling are essential for animal welfare and data quality. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages from planning to post-release monitoring.

Animal Capture and Restraint

The capture method (chemical immobilization, physical restraint, or remote capture) must be selected by professionals trained for the specific species. The goal is to minimize the duration of the capture event and the stress on the animal. For many marine mammals, procedures should be conducted on land when possible to reduce the risk of drowning [26]. A thorough health assessment should be performed prior to device attachment; animals showing signs of excessive stress or poor health should be released without a tag.

Device Attachment and Data Collection

The attachment site must be prepared according to best practices, which may involve cleaning, drying, and, for glued attachments, potentially shaving the area to improve adhesion [26]. The device should be attached swiftly and securely by a trained individual. Alongside attachment, researchers should collect valuable morphometric and biological data (e.g., weight, length, blubber thickness, blood, whisker, or fur samples) to maximize the scientific return from a single handling event, provided these activities do not unduly prolong the procedure.

Post-Release Monitoring and Impact Assessment

Monitoring the tagged animal after release is a critical but often overlooked component of ethical tagging. Direct observation immediately post-release can provide early indicators of adverse effects. Long-term monitoring via the tag itself and, where possible, subsequent re-sightings, is necessary to assess the device's impact on behavior, body condition, and survival. The gold standard for impact assessment is the use of a control population of untagged animals [27]. Comparing life-history traits like survival rates, reproductive success, and foraging efficiency between tagged and untagged individuals provides the most robust data on device effects and is essential for refining future protocols.

Data Management and Reporting Standards

Data Compilation and Standardization

The value of telemetry data is magnified when combined across studies, enabling large-scale analyses of animal movement and distribution. However, combining datasets is challenging due to variations in study design, tracking methods, and data structures. A standardized compilation pipeline is recommended, which includes phases for dataset pre-processing, formatting to a common template, binding, error checking, and filtering [20]. Such a pipeline helps flag erroneous locations (a known issue with satellite telemetry) and standardizes attributes for analysis [20]. Database projects like Movebank and the Marine Mammals Exploring the Oceans Pole to Pole (MEOP) consortium are leading efforts to store and standardize biologging data, making them accessible to the broader research community [27].

Transparent Reporting and Data Sharing

Full and transparent reporting of methods is essential for the critique, replication, and refinement of tagging protocols. Publications should include detailed information on:

- Device specifications (mass, dimensions, attachment method).

- Capture and handling protocols (duration, drugs used).

- Any observed or potential impacts on the animal. This level of detail allows for future meta-analyses that can improve best practices [27]. Furthermore, following the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) for data sharing maximizes the collective scientific return from the individual animal's contribution and aligns with the Reduction principle of the Three Rs.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for GPS Telemetry Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tag Types | GPS/Argos collars (terrestrial), CTD-SRDL tags (marine), Pop-up Archival Transmitting (PAT) tags | Gather and transmit fine-scale spatio-temporal data on location, behavior, and/or environmental conditions [29] [28] [27]. |

| Attachment Materials | Adhesives (epoxy, glue), custom-fitted harnesses, satellite bands | Securely affix the telemetry device to the animal's body in a way that minimizes drag and injury risk [26]. |

| Capture & Health Assessment | Chemical immobilants, biologgers for physiology (e.g., "daily diary" tags), stethoscope, blood collection kits | Safely restrain animals for tagging and collect baseline health and physiological data to assess procedure impact [27] [26]. |

| Data Infrastructure | Movebank, MEOP database, custom compilation pipelines | Store, standardize, error-check, and share the large volumes of tracking data generated [27] [20]. |

The ethical deployment of GPS telemetry tags requires a committed, ongoing practice of justification, refinement, and transparency. There is no single correct protocol; instead, best practices emerge from a conscientious application of general principles—the Three Rs—to the specific context of the research question and the target species. As a field, biologging must continue to advance on several fronts to uphold its ethical commitments.

Future directions should focus on:

- Technology Development: Creating smaller, smarter, and less invasive tags, including those that can collect data on the device's impact on the animal itself [27].

- Validation Studies: Conducting more rigorous, controlled studies to move beyond simplistic rules of thumb (e.g., 2-5% body weight rule) and build a predictive understanding of how device design and attachment affect different species [27].

- Standardized Experimental Design: Implementing robust study designs, including control populations, as a standard requirement for biologging studies to properly quantify impacts [27].

- Universal Data Sharing: Embracing a culture of open data through centralized databases to maximize knowledge gain per animal tagged and facilitate large-scale ecological analyses [27] [20].

By adhering to detailed, species-specific protocols and actively pursuing these future goals, researchers can ensure that the powerful tool of GPS telemetry continues to provide critical insights for ecology and conservation while maintaining the highest standards of animal welfare.

The field of wildlife telemetry has evolved beyond simple location tracking into a sophisticated discipline capable of capturing rich, multi-dimensional datasets about animal lives. Multi-sensor integration represents the cutting edge of this transformation, enabling researchers to move from merely documenting where an animal is to understanding what it is experiencing physiologically and environmentally in near real-time [1] [30]. Modern telemetry tags now function as mobile field laboratories, carrying suites of miniaturized sensors that capture behavioral, physiological, and environmental metrics simultaneously with position data [30]. This technological evolution is revolutionizing ecological research, conservation planning, and our fundamental understanding of species biology in a rapidly changing world.

The core advancement lies in the ability to correlate location data with contextual information. While GPS provides precise movement trajectories, integrated sensors reveal the underlying drivers and consequences of that movement—from the physiological cost of navigating difficult terrain to the environmental conditions an animal selectively experiences [28] [30]. This multi-dimensional approach has revealed critical limitations in studies relying solely on location data, which often force researchers to infer behavior and physiology indirectly [28]. By directly measuring these parameters, integrated sensor systems provide mechanistic understanding of animal movement, energy expenditure, health status, and response to environmental change.

The Integrated Sensor Toolkit: Capabilities and Applications

Modern animal-borne sensors can be broadly categorized into three functional classes: those measuring behavior, physiology, and environment. When deployed in combination, these sensors transform standard tracking studies into holistic investigations of animal ecology.

Table 1: Sensor Categories and Their Ecological Applications

| Sensor Category | Specific Metrics Measured | Research Applications | Example Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Sensors | Acceleration, tilt angle, direction, swimming depth/flight altitude, feeding events, proximity to conspecifics [30] | Quantifying energy expenditure, identifying specific behaviors (e.g., foraging, resting), studying social interactions, documenting predation events [30] | Tri-axial accelerometers, magnetometers, depth sensors, proximity loggers [30] |

| Physiological Sensors | Body temperature, heart rate (ECG), muscular activity, gastric activity, sound production [30] | Monitoring stress responses, estimating metabolic rate, tracking reproductive status (e.g., pregnancy), detecting illness [30] | Thermistors, implantable physio-loggers (e.g., Star-Oddi), acoustic transmitters [31] [30] |

| Environmental Sensors | Ambient temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, irradiance, magnetic field intensity [30] | Documenting habitat selection, mapping microclimates, studying climate change impacts, understanding oceanographic correlations [30] | CTD loggers, photodiodes, dissolved oxygen sensors, magnetometers [30] |

Behavioral Sensing Beyond Movement

Accelerometers have emerged as particularly versatile behavioral sensors. These devices measure the dynamic acceleration of an animal's body, providing high-resolution data that can be used to distinguish between walking, running, flying, swimming, and resting states with high certainty [30]. When combined with GPS data, accelerometry can reveal how landscape features influence energetic costs of movement. Additional behavioral sensors like magnetometers (measuring direction) and depth sensors provide crucial context for interpreting movement paths in three-dimensional environments [30].

Physiological Status Monitoring

The ability to monitor an animal's internal state represents a quantum leap in ecological telemetry. Implantable physio-loggers, some weighing as little as one gram, can measure core body temperature, ECG-based heart rate, and activity in diverse taxa [31]. These data streams provide insights into energy use, stress responses, feeding ecology, and migration physiology that were previously inaccessible without invasive laboratory studies [31] [30]. For example, heart rate patterns can indicate exercise intensity during migration, while body temperature profiles may reveal fever responses to infection.

Environmental Context Recording

Environmental sensors mounted on animal-borne tags effectively transform studied animals into biospheric probes that sample conditions within their immediate habitat [30]. These sensors document the precise environmental parameters an animal experiences, eliminating guesswork about habitat characteristics. For marine species, tags can measure salinity, depth, and water temperature [30]. For terrestrial species, ambient temperature and irradiance sensors can reveal microclimate selection [30]. For species navigating using Earth's magnetic field, magnetometers can document field intensity during movements [30].

Figure 1: Architecture of an integrated multi-sensor telemetry tag showing the convergence of behavioral, physiological, and environmental data streams into a unified dataset for ecological analysis.

Data Processing, Transmission, and Analysis Frameworks

The rich data streams generated by multi-sensor tags present significant challenges in data processing, transmission, and analysis. Effective integration requires specialized hardware and software approaches to transform raw sensor readings into biologically meaningful information.

Data Transmission and Platform Considerations

The choice of data transmission technology represents a critical trade-off between device weight, data volume, battery life, and geographic coverage. Satellite-based systems (Argos, Iridium) enable global tracking but have limited bandwidth for transmitting high-volume sensor data [1]. GSM networks offer higher data throughput but are restricted to areas with cellular coverage [1]. Emerging satellite constellations specifically designed for IoT connectivity, such as the 25 nanosatellites being deployed by Kinéis, promise improved data transmission from remote areas using low-cost, low-energy devices [1]. For studies requiring high temporal resolution sensor data, on-board data logging with future recovery remains the only viable option for some applications, despite the obvious limitations [14].

Table 2: Data Transmission Technologies for Multi-Sensor Tags

| Transmission Technology | Data Capability | Coverage | Power Requirements | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite (Argos/Iridium) | Low-moderate data volume | Global | High | Long-distance migrants, marine species, remote regions [1] |

| GSM Cellular Networks | Moderate-high data volume | Network coverage areas | Moderate | Peri-urban and suburban species, areas with reliable coverage [1] |

| LoRaWAN/Sigfox | Low data volume, long range | 5-200 km with local antennas | Low | Regional movements, fixed study areas [31] |

| Archival (Data Logging) | Very high data volume | Not applicable | Very low | All applications where recapture is feasible [14] |

| UHF Telemetry | Moderate data volume, high resolution | Local (up to several km) | Low | Fine-scale habitat use, behavior studies [31] |

Analytical Approaches for Integrated Data

The analysis of multi-sensor telemetry data requires specialized statistical approaches that can handle high-dimensional, correlated data streams with varying temporal structures [28]. Machine learning techniques, particularly supervised classification, have proven highly effective for identifying behavioral states from accelerometry data when combined with ground-truthed observations [30]. For spatial data, new algorithms like the grid search method for automated radio telemetry systems can significantly improve localization accuracy by comparing received signal strength across multiple receivers and finding the optimal fit to signal propagation models [18].

The integration of different data types often reveals emergent properties not apparent from any single data stream. For example, combining acceleration data (indicating active movement) with heart rate data (indicating metabolic cost) can reveal the energetic efficiency of different locomotion strategies. Similarly, correlating body temperature measurements with ambient environmental conditions can quantify thermal stress and behavioral thermoregulation [30]. These analytical approaches move beyond simple correlation to establish mechanistic links between animal physiology, behavior, and environment.

Essential Research Reagents and Equipment Solutions

Implementing a successful multi-sensor tracking study requires careful selection of hardware, software, and supporting technologies. The following table summarizes key solutions available from commercial suppliers and research institutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Sensor Telemetry Studies

| Product Category | Example Suppliers | Key Specifications | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS/Satellite Tags with Sensors | e-obs, Vectronic Aerospace, Lotek, Telenax [31] | GPS with accelerometers, environmental sensors; remote data download; customizable sampling [31] | High-resolution movement studies; large mammal ecology; habitat selection [31] |

| Miniature Physio-Loggers | Star-Oddi [31] | Implantable design; measures temperature, heart rate, activity; devices as small as 1g [31] | Physiological monitoring in small vertebrates and aquatic species; metabolic studies [31] |

| Customizable IoT Sensors | Hardwario, Copernicus Technologies [1] [31] | Long battery life (years); multiple daily transmissions; customizable sensors [1] | Long-term environmental monitoring; anti-poaching applications; regional tracking [1] |

| Automated Radio Telemetry | Ecotone [31] | Very light tags (≥60mg); multiple receiver arrays; high temporal resolution [18] | Small species tracking; fine-scale movement ecology; insect and herpetological studies [18] |

| Data Visualization Platforms | Mapotic [1] | Interactive mapping; data randomization for protection; public engagement tools [1] | Citizen science projects; conservation advocacy; educational applications [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Integrated Sensor Study

The following protocol provides a framework for implementing a comprehensive multi-sensor tracking study, from hypothesis development through data analysis. This workflow integrates both technological and biological considerations to ensure robust experimental design and meaningful results.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for implementing an integrated multi-sensor tracking study, showing key stages from initial planning through final data analysis.

Study Planning and Design Phase

Objective: Establish a clear conceptual framework linking research questions to specific sensor measurements.

Procedure:

- Define Primary Research Questions: Formulate specific, testable hypotheses that require integrated sensor data. Example: "Do elevated heart rates during mountain lion movements through urban interfaces indicate physiological stress responses?"

- Identify Critical Parameters: Select the minimum set of sensors needed to address research questions while respecting animal welfare constraints [14]. Consider both direct measurements (e.g., heart rate) and proxy measurements (e.g., activity from accelerometers as an indirect measure of energy expenditure).

- Determine Resolution Requirements: Establish the necessary temporal and spatial resolution for each data stream. Balance resolution against battery life and data storage/transmission limitations [14] [18].

- Power Analysis: Conduct statistical power analysis to determine appropriate sample sizes, considering potential tag failure rates and the trade-off between number of tags and cost [28]. GPS studies often suffer from small sample sizes due to high per-unit costs, potentially limiting population-level inference [28].

Hardware Selection and Configuration

Objective: Select appropriate tagging technologies that balance measurement capabilities with animal welfare considerations.

Procedure:

- Tag Selection: Choose tags that do not exceed 3-5% of the animal's body mass, with the lower threshold preferred for migratory species [14]. For species under 200g, specialized lightweight tags (e.g., Doppler PTT tags around 2g) may be necessary [14].

- Sensor Integration: Select a sensor suite that addresses research questions while minimizing size and power requirements. Consider integrated tags from commercial suppliers (e.g., e-obs, Vectronic Aerospace) that combine GPS with accelerometers and environmental sensors [31].

- Data Transmission Method: Choose between archival logging (requiring recapture), satellite transmission (global but limited bandwidth), GSM networks (higher throughput where available), or LoRaWAN/Sigfox (long-range, low-power for regional studies) based on study species and geography [1] [31].

- Attachment Method Testing: Test attachment methods (leg-loop harnesses, collars, adhesives, implants) on captive animals or models to ensure secure attachment while minimizing welfare impacts. Use degradable materials where appropriate to ensure eventual release [14].

Field Deployment and Data Collection

Objective: Deploy sensors on study animals and establish continuous data collection systems.

Procedure:

- Regulatory Compliance: Obtain all necessary permits and IACUC/animal ethics approvals before beginning fieldwork [32] [33]. Consult with veterinarians during protocol development, particularly for invasive procedures [32].

- Animal Capture and Handling: Use species-appropriate capture methods that minimize stress and risk to animals. Monitor vital signs during handling and abort procedures if animals show signs of severe distress.

- Tag Attachment: Apply tags using predetermined attachment methods. Record individual animal measurements (weight, size, condition) and any relevant biological samples at time of tagging.

- Post-Release Monitoring: When possible, observe tagged animals immediately after release to ensure normal behavior and assess short-term responses to tagging.

- Data Collection Infrastructure: Maintain and monitor receiver networks (satellite, GSM, or fixed stations) to ensure continuous data capture. Implement automated data quality checks to identify system failures promptly [18].

Data Integration and Analysis

Objective: Transform multi-sensor data streams into integrated datasets for analytical testing of research hypotheses.

Procedure:

- Data Cleaning: Apply sensor-specific calibration curves and filters to raw data. Identify and remove biologically implausible values resulting from sensor artifacts.

- Time Synchronization: Align all data streams to a common time standard, accounting for potential clock drift in individual tags.

- Sensor Fusion: Implement analytical approaches that combine data streams to create novel derived metrics. Examples include:

- Energy Expenditure: Combine accelerometry and heart rate data to estimate metabolic cost [30].

- Behavior Classification: Use machine learning to classify behavior states from acceleration patterns validated with direct observation [30].

- Environmental Correlates: Spatially explicit analysis of physiological metrics in relation to environmental conditions [30].

- Statistical Modeling: Apply appropriate statistical models that account for autocorrelation in time-series data and individual variation. Use mixed-effects models to separate population-level patterns from individual idiosyncrasies [28].

Multi-sensor integration represents the future of wildlife telemetry, transforming simple tracking devices into comprehensive biological monitoring platforms. The technology continues to advance toward smaller sizes, longer battery life, greater sensor diversity, and more sophisticated on-board processing capabilities. Emerging technologies like fluorescent tagging systems (e.g., BrightMarkers) may eventually enable non-invasive tracking of smaller species [34], while continued miniaturization will make integrated sensors available for progressively smaller taxa.

The ultimate promise of multi-sensor integration lies in its ability to create holistic portraits of animal lives—revealing not just movement paths, but the physiological costs of navigation, the environmental challenges faced, and the behavioral strategies employed to overcome them. As these technologies become more accessible and analytical methods more sophisticated, integrated sensor approaches will dramatically advance our understanding of animal ecology in rapidly changing environments and provide crucial insights for conservation management in the Anthropocene.

The study of animal movement has been revolutionized by advances in telemetry technology, with GPS telemetry tags serving as a cornerstone of modern movement ecology research [35]. These technologies have enabled a shift from discrete, small-scale studies to large-scale, collaborative networks that can generate unprecedented volumes of data and novel ecological insights. The 2025 Monarch Tracking Project represents a paradigm shift in this field, demonstrating how technological innovation combined with structured scientific collaboration can overcome previous limitations in tracking small, migratory species across continental scales.

This application note examines the Project Monarch collaboration as a case study in large-scale ecological research, detailing the groundbreaking technological specifications, experimental protocols, and data management frameworks that enabled the successful tracking of individual monarch butterflies from Canada to their Mexican overwintering sites. The project deployed over 400 ultralight transmitters across more than 20 partner organizations throughout North America, establishing a new model for collaborative wildlife telemetry research [15] [36].

The 2025 Monarch Tracking Project addressed a longstanding challenge in movement ecology: tracking small-scale migratory organisms throughout their complete migration cycle. Prior to this initiative, conventional tracking technology was too heavy for monarch butterflies, which weigh less than a gram, forcing researchers to rely on indirect methods or mark-recapture studies that provided limited data on migration pathways and survival [37]. The project's success has shattered these limitations, providing scientists with high-resolution, near-real-time data on individual butterflies as they navigate their epic journey south [15].

Table: Key Quantitative Metrics of the 2025 Monarch Tracking Project

| Project Aspect | Metric | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | >20 organizations across 4 countries | Demonstrates extensive collaborative framework |

| Technology Deployment | >400 BlūMorpho transmitters deployed | Unprecedented tracking capacity for small insects |

| Transmitter Weight | 60 milligrams | ~80% reduction from previous 0.15g proof-of-concept |

| Tracking Resolution | Near-real-time with high spatial accuracy | Enabled fine-scale movement analysis |

| Detection Network | Millions of smartphones as passive receivers | Novel approach to continental-scale coverage |

The project's significance extends beyond monarch conservation, serving as a proof-of-concept for collaborative research frameworks that can be applied to other migratory species. By pooling resources and data across institutions, the collaboration created something "far greater than the sum of its parts," in the words of Dr. David La Puma, Director of Global Market Development at Cellular Tracking Technologies [36]. This model demonstrates how standardized protocols and data-sharing agreements can facilitate powerful analyses that would be impossible for individual research groups.

Technological Specifications

The core innovation enabling the 2025 Monarch Tracking Project was the development of the BlūMorpho transmitter by Cellular Tracking Technologies (CTT). This revolutionary telemetry tag represents a significant advancement in miniaturization technology for wildlife tracking.

BlūMorpho Transmitter Specifications

The BlūMorpho transmitter weighs approximately 60 milligrams, making it the world's lightest wildlife transmitter and sufficiently lightweight for monarch butterflies [36]. This achievement required overcoming substantial engineering challenges that had previously made monarch tracking impossible. The breakthrough came in 2021 when CTT engineer Eric Johnson identified a new chipset, and the company leveraged in-house advanced manufacturing techniques including custom solar panels the size of a grain of rice and surface mount technology that enabled assembly of precision circuitry [15].

Table: Technical Specifications of BlūMorpho Transmitters

| Parameter | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | 60 mg | Represents critical threshold for insect tracking |

| Power Source | Solar-powered | Enables extended operation during migration |

| Operating Frequency | 2.4 GHz (Bluetooth) | Compatible with consumer devices |

| Detection Range | Variable based on receiver density | Enhanced by crowd-sourced network |

| Data Transmission | Bluetooth with Blū+ code enhancement | Enables smartphone detection |

Detection Network Infrastructure

The project employed a multi-layered detection network consisting of both dedicated wildlife receivers and everyday smartphones. The infrastructure included:

- Traditional Wildlife Receivers: Motus Wildlife Tracking System stations and Terra mini base stations provided dedicated detection capability [15].

- Smartphone Integration: The Project Monarch App transformed smartphones into passive receivers, creating an extensive crowd-sourced detection network [36].

- Blū+ Programming Code: Enhanced transmitters included additional programming that enabled them to tap into crowd-sourced location networks, dramatically increasing detection points [15].

The pivotal moment in network development occurred in November 2024 when a butterfly named "Lionel," equipped with the Blū+ code, provided the first high-resolution track of monarch migration ever recorded, with hundreds of detections along its route to St. Augustine, Florida [36]. This demonstrated the potential of leveraging existing consumer technology to create continental-scale tracking networks.

Diagram 1: BlūMorpho Detection Network Architecture. The system integrates dedicated receivers and consumer smartphones to create continental-scale tracking capability.

Experimental Protocols

Transmitter Deployment Protocol

The deployment of BlūMorpho transmitters on monarch butterflies followed standardized protocols to ensure data quality and animal welfare:

- Butterfly Capture: Monarchs were captured using standard aerial nets during their fall migration period. Care was taken to minimize wing damage and stress during capture.

- Sex Determination: Each individual was sexed based on wing morphology (males have a distinct black spot on each hind wing).

- Transmitter Attachment: The 60-milligram BlūMorpho transmitter was carefully affixed to the butterfly's thorax using a specially formulated, non-toxic adhesive that ensured secure attachment without impairing flight capability.

- Release Procedure: Tagged butterflies were released at the location of capture following a brief recovery period, with precise geographic coordinates recorded via GPS.

- Data Recording: For each deployment, researchers recorded the complete tag code, deployment date, sex of the butterfly, geographic location, and other relevant metadata [15].

The project incorporated research from James Madison University that quantified effects of tags on movement and behavior, confirming that survival was unlikely to be impacted in properly tagged individuals [15]. This welfare consideration was essential for ensuring ethical research practices and valid scientific results.

Data Collection and Management Protocol

The project implemented a rigorous data management pipeline to handle the volume and complexity of movement data generated by the tracking network:

- Data Acquisition: Location data was collected through multiple streams including dedicated receivers and the smartphone network.

- Pre-processing: Raw data underwent cleaning procedures to remove location errors and outliers that could misrepresent movement paths [21].

- Standardization: Data from multiple partners was formatted to a common template with standardized fields, enabling integration across the collaboration [20].

- Error Checking: Automated error checks flagged biologically implausible locations (e.g., sudden long-distance movements inconsistent with monarch flight capabilities).