Handling Large Movement Datasets: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing and analyzing large-scale human movement data.

Handling Large Movement Datasets: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing and analyzing large-scale human movement data. It covers the entire data lifecycle—from foundational principles and collection standards to advanced methodological approaches, optimization techniques for computational efficiency, and rigorous validation frameworks. Readers will learn practical strategies to overcome common challenges, leverage modern AI and machine learning tools, and ensure their data practices are reproducible, ethically sound, and capable of generating robust, clinically relevant insights.

Understanding Large Movement Data: From Collection to Clinical Relevance

Defining Large Movement Datasets in Biomedical Contexts (e.g., kinematics, kinetics, EMG)

FAQs: Understanding Large Movement Datasets

What defines a "large dataset" in movement biomechanics? A large dataset is defined not just by absolute size, but by characteristics that cause serious analytical "pain." This includes having a large number of attributes (high dimensionality), heterogeneous data from different sources, and complexity that requires specialized computational methods for processing and analysis [1]. In practice, datasets from studies involving hundreds of participants or multiple measurement modalities (kinematics, kinetics, EMG) typically fall into this category [2].

What are the key statistical challenges when analyzing large biomechanical datasets? Large movement datasets present several salient statistical challenges, including:

- High Dimensionality: A large number of attributes describing each sample, which can lead to overfitting and the "curse of dimensionality" where traditional statistical methods break down [1].

- Multiple Testing: Performing numerous statistical tests increases the likelihood of observing significant results purely by chance, requiring appropriate correction methods [1].

- Dependence: Data samples and attributes are often not independent or identically distributed, violating key statistical assumptions [1].

How can I ensure my large dataset is reusable and accessible to other researchers? Providing comprehensive metadata is essential for dataset reuse. This should include detailed participant demographics, injury status, collection protocols, and data processing methods. For example, one large biomechanics dataset includes metadata covering subject age, height, weight, injury definition, joint location of injury, specific injury diagnosis, and athletic activity level [2]. Standardized file formats and clear documentation also enhance reusability.

What equipment is typically required to capture large movement datasets? Gold standard motion capture typically requires:

- Optical Motion Capture Systems: Multi-camera systems (e.g., Vicon, 12 cameras) to track 3D marker positions at high frequencies (200 Hz) [3].

- Force Plates: To measure ground reaction forces and moments (typically at 2000 Hz) [3].

- EMG Systems: To record muscle activity (typically at 2000 Hz) [3].

- Synchronization Hardware: To ensure temporal alignment across all data streams [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent or Noisy Kinematic Data

Problem: Marker trajectories show excessive gaps, dropout, or noise during dynamic movements, particularly during activities with high intensity or obstruction.

Solution:

- Repeat the experiment: Unless cost or time prohibitive, repeating the trial might resolve simple mistakes in execution [4].

- Verify equipment setup:

- Check camera calibration using a standardized wand [3].

- Ensure adequate camera coverage of the movement volume.

- Confirm reflective markers are securely attached and visible from multiple angles.

- Systematically test variables:

- Adjust marker placement to minimize skin motion artifact.

- Test different filtering parameters (e.g., try a fourth-order Butterworth filter at varying cutoff frequencies, with 10 Hz being a reference point used in some gait studies) [2].

- Experiment with gap-filling algorithms in your motion capture software.

Issue: Weak or Absent EMG Signals

Problem: EMG recordings show minimal activity even during maximum voluntary contractions, or signals are contaminated with noise.

Solution:

- Confirm the experiment actually failed: Consider whether the biological reality matches your expectations. Dim signals could indicate proper muscle relaxation rather than technical failure [4].

- Check electrode placement and skin preparation:

- Verify equipment function:

- Check EMG sensor synchronization with other data streams (note that constant delays can sometimes be corrected post-hoc) [3].

- Test different amplifier gains.

- Ensure proper grounding and check for electrical interference sources.

Issue: Managing Computational Complexity in Large Dataset Analysis

Problem: Data processing and analysis workflows become prohibitively slow with large participant numbers or high-dimensional data.

Solution:

- Implement appropriate data reduction techniques:

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality while preserving variance [2].

- Focus on key gait events and phases rather than continuous data streams.

- Optimize computational methods:

- Utilize specialized biomechanical analysis software (e.g., 3D GAIT) for efficient joint angle calculations [2].

- Implement code-based solutions for batch processing of multiple subjects.

- Consider parallel processing for independent analyses.

Comparative Analysis of Large Movement Datasets

The table below summarizes characteristics of exemplar large biomechanical datasets as referenced in the literature:

Table 1: Characteristics of Exemplar Large Biomechanical Datasets

| Dataset Focus | Subjects (n) | Data Modalities | Key Activities | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy and Injured Gait [2] | 1,798 | Kinematics, Metadata | Treadmill walking, running | Includes injured participants (n=1,402), large sample size, multiple speeds |

| Daily Life Locomotion [5] | 20 | Kinematics, Kinetics, EMG, Pressure | 23 daily activities | Comprehensive activity repertoire, multiple sensing modalities |

| Amputee Sit-to-Stand [3] | 9 | Kinematics, Kinetics, EMG, Video | Stand-up, sit-down | Focus on above-knee amputees, first of its kind for this population |

Table 2: Statistical Challenges in Large Biomechanical Datasets

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Analysis | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Dimensionality [1] | Many attributes (variables) per sample | Increased risk of overfitting; reduced statistical power | Dimensionality reduction (PCA); regularization methods |

| Multiple Testing [1] | Many simultaneous hypothesis tests | Increased false positive findings | Correction procedures (Bonferroni, FDR) |

| Dependence [1] | Non-independence of samples/attributes | Invalidated statistical assumptions | Appropriate modeling of covariance structures |

Experimental Protocols for Large Dataset Collection

Protocol: Comprehensive Motion Analysis for Lower Limb Biomechanics

Objective: To collect synchronized kinematic, kinetic, and electromyographic data during dynamic motor tasks.

Equipment Setup:

- Motion Capture: 12-camera system (e.g., Vicon Vantage) capturing at 200 Hz [3].

- Force Plates: Two in-ground force plates (e.g., AMTI OR6-7) sampling at 2000 Hz [3].

- EMG: Wireless sensors (e.g., Delsys Trigno Avanti) on key muscles, sampling at 2000 Hz [3].

- Synchronization: All devices synchronized through motion capture software (e.g., Vicon Nexus) [3].

Marker Placement:

- Apply reflective markers (14mm diameter) using hypoallergenic tape following a modified Plug-In-Gait model [3].

- Place markers on anatomical landmarks: medial/lateral malleoli, femoral condyles, greater trochanters [2].

- For more detailed modeling, add markers on metatarsal heads, tibial tuberosity, and pelvic landmarks [2].

- Use rigid marker clusters on segments (thigh, shank, sacrum) for dynamic tracking [2].

Calibration Sequence:

- Static Trial: Subject stands in neutral position with feet shoulder-width apart [3].

- Functional Trial: Subject performs lower limb "star arc" movements and squats to define joint centers and ranges of motion [3].

Data Collection:

- Position subjects with one foot on each force plate [3].

- Collect multiple trials (typically 3-5) of each activity (e.g., standing, sitting, sit-to-stand) [3].

- For walking/running studies, collect 20-60 seconds of continuous data at self-selected comfortable speeds [2].

Protocol: EMG Integration with Motion Capture

Electrode Placement:

- Identify muscle bellies for target muscles (e.g., Vastus Medialis, Biceps Femoris, Gastrocnemius, Tibialis Anterior) [3].

- Prepare skin by shaving and cleaning with alcohol [3].

- Apply EMG sensors following SENIAM recommendations [3].

- Secure sensors with elastic co-adhesive wrapping or kinesiology tape to maintain contact during movement [3].

Synchronization Verification:

- Confirm temporal alignment of EMG with kinematic and kinetic data through software synchronization [3].

- If delays are detected, apply constant frame correction during data processing [3].

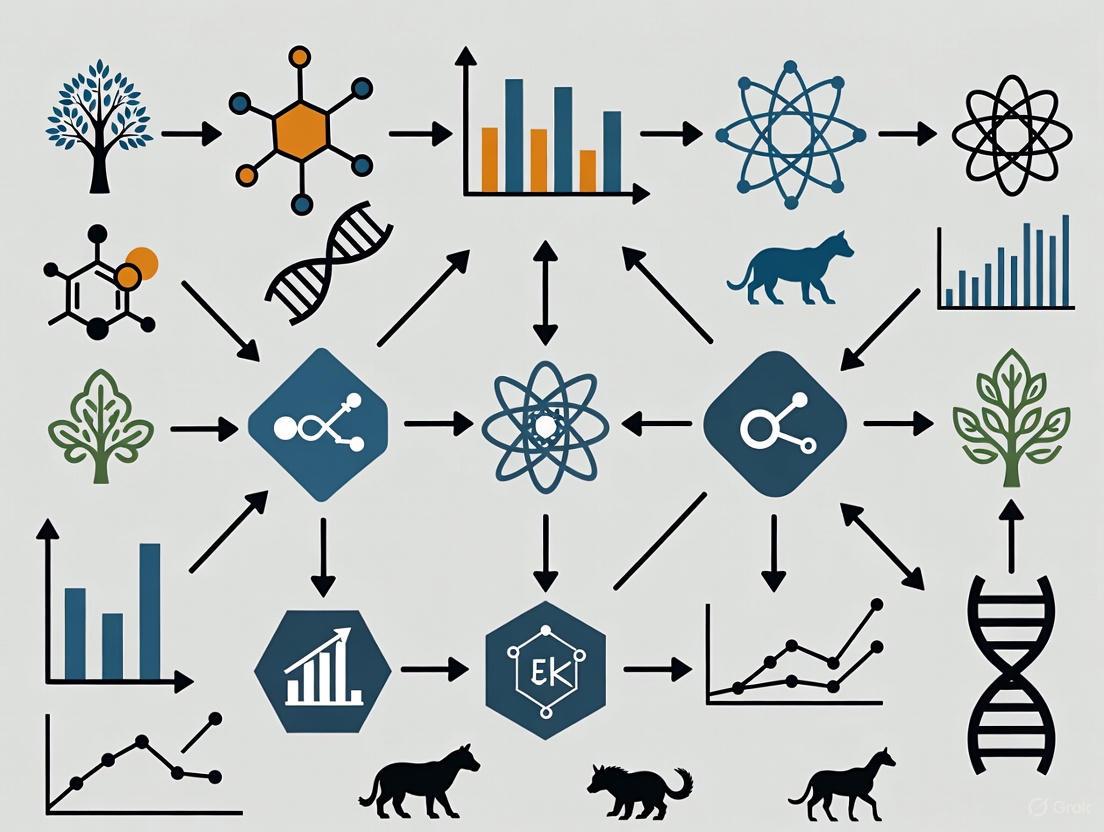

Visualizing Analysis Workflows

Diagram 1: Analysis workflow for large movement datasets, highlighting key stages and associated data challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Equipment for Biomechanical Data Collection

| Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Key Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Capture Systems | Vicon Vantage cameras [3] | Track 3D marker positions | 12 cameras, 200 Hz sampling |

| Force Measurement | AMTI OR6-7 force plates [3] | Measure ground reaction forces | 2000 Hz sampling, multiple plates |

| EMG Systems | Delsys Trigno Avanti sensors [3] | Record muscle activation | 2000 Hz, wireless synchronization |

| Reflective Markers | 14mm spherical retroreflective [3] | Define anatomical segments | Modified Plug-In-Gait set |

| Data Processing Software | Vicon Nexus, 3D GAIT [2] | Process raw data into biomechanical variables | Joint angle calculation, event detection |

The Critical Importance of Data Governance and FAIR Principles

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FAIR Data Implementation Issues

Data Cannot Be Found by Collaborators

- Problem: Other researchers or automated systems report being unable to locate your dataset.

- Solution: Ensure your data is assigned a Globally Unique and Persistent Identifier, such as a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), and that both data and metadata are indexed in a searchable resource [6] [7].

- Prevention: Deposit your dataset in a reputable repository that provides persistent identifiers and registers data with major search indexes [8].

Metadata is Incomprehensible to Machines

- Problem: Computational tools cannot parse your data descriptors to understand the context or content of your data.

- Solution: Use a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation. This includes using community-standardized vocabularies, ontologies, and thesauri [6] [7].

- Prevention: Structure your metadata using machine-readable standards like XML or JSON and leverage existing community-approved ontologies for your field [7] [8].

Data Access Requests Fail or are Overly Complex

- Problem: Users who find your data cannot retrieve it, or the authentication and authorization process is unclear.

- Solution: Ensure data is retrievable by its identifier using a standardized, open, and free communications protocol (e.g., HTTPS). If access is restricted, clearly document the path for legitimate access requests [6] [9].

- Prevention: Choose data repositories that support stable interfaces and APIs and clearly specify access procedures and license conditions in the metadata [7].

Data Cannot be Integrated with Other Datasets

- Problem: Your data cannot be seamlessly combined with other internal or public datasets for analysis.

- Solution: Store data in open, standard file formats (e.g., CSV, XML, JSON) and ensure it uses shared vocabularies. The data should include qualified references to other (meta)data [7] [9].

- Prevention: Implement common data models, such as the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model, which standardizes data representation to ensure semantic and syntactic interoperability [10].

Data Reuse Leads to Incorrect Interpretation

- Problem: Those who try to reuse your data misinterpret variables or methodology, leading to errors.

- Solution: Richly describe your data with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes. This must include a clear data usage license, detailed provenance (how the data was generated and processed), and adherence to domain-relevant community standards [6] [7].

- Prevention: Create comprehensive documentation, such as a README file, that explains the methodology, variable definitions, units, and any data quality checks performed [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between FAIR and Open Data?

A: FAIR data is designed to be machine-actionable, focusing on structure, rich metadata, and well-defined access protocols—it does not necessarily have to be publicly available. Open data is focused on being freely available to everyone without restrictions, but it may lack the structured metadata and interoperability that makes it easily usable by computational systems [9]. FAIR data can be closed or open access.

Why is machine-actionability so emphasized in the FAIR principles?

A: Due to the vast volume, complexity, and creation speed of contemporary scientific data, humans increasingly rely on computational agents to undertake discovery and integration tasks. Machine-actionability ensures that these automated systems can find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention, enabling research at a scale and speed that is otherwise impossible [11] [7].

Our data is sensitive. Can it still be FAIR?

A: Yes. FAIR is not synonymous with "open." The Accessible principle specifically allows for authentication and authorization procedures. Metadata should remain accessible even if the underlying data is restricted, describing how authorized users can gain access under specific conditions [7] [10]. This is particularly relevant for human subjects data governed by privacy regulations like GDPR [10].

What is the first step in making our legacy data FAIR?

A: Begin with an assessment and strategy development phase [12] [13]. This involves identifying and prioritizing the data assets most valuable to your key business problems or research use cases. Then, establish the core data governance framework, including policies, roles (like data stewards), and procedures, before deploying technical solutions [12].

How does Data Governance relate to the FAIR Principles?

A: Data Governance provides the foundational framework of processes, policies, standards, and roles that ensures data is managed as a critical asset [12]. Implementing the FAIR Principles is a key objective within this framework. Effective governance ensures there is accountability, standardized processes, and quality control, which are all prerequisites for creating and maintaining FAIR data [12] [13].

FAIR Principles Breakdown and Implementation Metrics

The table below summarizes the core FAIR principles and provides key metrics for their implementation.

| Principle | Core Objective | Key Implementation Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Data and metadata are easy to find for both humans and computers [6]. | - Assignment of a Globally Unique and Persistent Identifier (e.g., DOI) [7]. - Rich metadata is provided [7]. - Metadata includes the identifier of the data it describes [6]. - (Meta)data is registered in a searchable resource [6]. |

| Accessible | Users know how data can be accessed, including authentication/authorization [6]. | - (Meta)data are retrievable by identifier via a standardized protocol (e.g., HTTPS) [7]. - The protocol is open, free, and universally implementable [7]. - Metadata remains accessible even if data is no longer available [7]. |

| Interoperable | Data can be integrated with other data and used with applications or workflows [6]. | - (Meta)data uses a formal, accessible, shared language for knowledge representation [7]. - (Meta)data uses vocabularies that follow FAIR principles [7]. - (Meta)data includes qualified references to other (meta)data [7]. |

| Reusable | Metadata and data are well-described so they can be replicated and/or combined in different settings [6]. | - Meta(data) is richly described with accurate and relevant attributes [7]. - (Meta)data is released with a clear and accessible data usage license [7]. - (Meta)data is associated with detailed provenance [7]. - (Meta)data meets domain-relevant community standards [7]. |

FAIR Data Implementation Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the workflow for implementing FAIR principles, from planning to maintenance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key resources and tools essential for implementing robust data governance and FAIR principles in a research environment.

| Item / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Trusted Data Repository | Provides persistent identifiers (DOIs), ensures long-term preservation, and offers standardized access protocols, directly supporting Findability and Accessibility [7] [8]. |

| Common Data Model (e.g., OMOP CDM) | A standardized data model that ensures both semantic and syntactic interoperability, allowing data from different sources to be harmonized and analyzed together [10]. |

| Metadata Standards & Ontologies | Formal, shared languages and vocabularies (e.g., from biosharing.org) that describe data, enabling Interoperability and accurate interpretation by both humans and machines [7] [10]. |

| Data Governance Platform (e.g., Collibra, Informatica) | Software tools that help automate data governance processes, including cataloging data, defining lineage, classifying data, and managing data quality [12]. |

| Data Usage License | A clear legal document (e.g., Creative Commons) that outlines the terms under which data can be reused, which is a critical requirement for the Reusable principle [7] [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Informed Consent

Q1: What specific information must be included in an informed consent form for sharing large-scale human movement data? A comprehensive informed consent form for movement data research should be explicit about several key areas to ensure participants are fully informed [14] [15]. You must clearly state:

- The purpose of data collection: Specify the primary research objectives [16].

- The types of data being collected: Detail all data modalities, such as kinematics, kinetics, electromyography (EMG), and any associated metadata [14].

- Data sharing intentions: Explicitly state that the data may be shared with third parties for future scientific research, including the possibility of collaboration with commercial entities, and whether data will be shared in anonymized or coded form [16].

- Participant rights: Clearly explain the right to withdraw consent at any time and the procedures for doing so [17] [15].

- Data storage and security: Inform participants about the data's storage duration, security measures, and the level of de-identification (anonymization or pseudonymization) that will be applied [16] [17].

Q2: Can I rely on "broad consent" for the secondary use of movement data in research not originally specified? The use of broad consent, where participants agree to a wide range of future research uses, is a recognized model under frameworks like the GDPR, particularly when specific future uses are unknown [15]. However, its ethical application depends on several factors:

- Ethical Review: The research must receive approval from a designated ethics review committee [16] [15].

- Safeguards: Strong safeguards must be in place, including data anonymization and secure processing environments [15].

- Participant Control: Where feasible, dynamic or meta-consent models are increasingly recommended. These models provide participants with more ongoing control, allowing them to choose their preferred consent model for future studies or withdraw consent via user-friendly platforms [15].

- Legal Basis: Ensure you have a valid legal basis for processing under regulations like GDPR, such as public interest tasks for university research or a legitimate interests assessment for private researchers [18].

Data Sharing and Governance

Q3: What are the fundamental ethical pillars I should consider before sharing a dataset? Before sharing any research data, you should ensure your practices are aligned with the following core ethical pillars [17] [19]:

- Respect for Privacy and Consent: Protect personal data by securing informed consent and implementing strong data protection measures.

- Transparency and Accountability: Be open about data collection methods, usage, and establish clear oversight mechanisms.

- Fairness and Non-Discrimination: Actively identify and mitigate biases in datasets and algorithms to ensure equitable outcomes.

- Data Minimization: Collect and share only the data strictly necessary for the specified research purpose [17].

Q4: My dataset contains kinematic and EMG data. What are the key steps for making it FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable)? To make a multi-modal movement dataset FAIR, follow these guidelines structured around the data lifecycle [14]:

- Plan & Collect: Ensure informed consent for data sharing is obtained at the outset. Use comprehensive metadata templates to document all aspects of data collection (e.g., sensor placement, task protocols) [14].

- Process & Analyze: Use open, non-proprietary data formats (like C3D) to ensure long-term readability and interoperability. Maintain the raw data where possible [14].

- Share & Preserve: Select an appropriate data repository (e.g., Zenodo, Dryad) and assign a persistent identifier (DOI). Publish the data under a clear license and include a detailed data availability statement in any related publications [14] [20].

Q5: What should be included in a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA) or Data Transfer Agreement (DTA)? A robust DSA or DTA is critical for governing how shared data can be used. Key elements include [16]:

- Purpose Limitation: A clear definition of the specific scientific research questions the data can be used to address [16].

- Security Requirements: Specification of all appropriate technical and organizational measures the recipient must implement to secure the data [16].

- Use Restrictions: Clauses prohibiting attempts to re-identify individuals and restricting data use to the approved protocol.

- Publication and Acknowledgement Policies: Terms governing how the data should be cited in publications.

- Data Disposition: Requirements for data deletion or return after the agreement concludes.

Legal and Regulatory Compliance

Q6: How do international regulations like the GDPR impact the sharing of movement data, especially across borders? The GDPR imposes strict requirements on processing and transferring personal data, which can include detailed movement data [17] [18]. Key considerations are:

- Legal Basis: You must establish a lawful basis for processing (e.g., explicit consent, public interest task) [18].

- Data Anonymization: Truly anonymized data falls outside GDPR scope. However, the threshold for anonymization is high, and pseudonymized data is still considered personal data [15].

- International Transfer: Transferring personal data outside the European Economic Area (EEA) requires specific legal mechanisms, such as Adequacy Decisions or Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), and should be noted in your Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Managing Evolving Consent for Long-Term Research Projects

Problem: Participants wish to withdraw consent or change their data-sharing preferences after the dataset has been widely shared.

Solution: Implement a dynamic consent management framework.

| Step | Action | Considerations & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Utilize a Consent Platform. Adopt a web-based or app-based platform that allows participants to view and update their preferences easily. | Platforms can range from simple web forms to more advanced systems using Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) for greater user control [15]. |

| 2 | Record Consent Immutably. Use a blockchain-based system to create a tamper-proof audit trail of consent transactions, providing trust and transparency for both participants and researchers. | Blockchain and smart contracts can record consent changes without storing the personal data itself, enhancing security [21] [15]. |

| 3 | Communicate Changes. The system should automatically notify all known data recipients of any consent withdrawal. | This is a complex step; as a practical minimum, flag the participant's status in your master database and do not include their data in future sharing activities [15]. |

| 4 | Manage Data in the Wild. Acknowledge the technical difficulty of deleting data already shared. Annotate your master dataset and public data catalogs to indicate that consent for this participant's data has been withdrawn. | This is a recognized challenge. Transparency about the status of the data is the best practice when full deletion is not feasible. |

Issue 2: Preparing a Dataset for Sharing in a Secure Access Repository

Problem: Ensuring a dataset is both useful to other researchers and compliant with ethical and legal obligations before depositing it in a controlled-access repository.

Solution: Follow a structured pre-sharing workflow.

Diagram 1: Data Pre-Sharing Workflow

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Apply Robust De-identification: Go beyond removing direct identifiers (names, IDs). For movement data, consider techniques like adding noise to data, shifting dates, or categorizing continuous variables to reduce re-identification risk from unique movement patterns [15].

- Assess Re-identification Risk: Systematically evaluate whether the dataset could be linked with other public data to re-identify individuals. If the risk is high, return to Step 1 and apply further anonymization techniques [18].

- Create Comprehensive Metadata: Document everything a researcher would need to understand and reuse the data. Use community-developed templates to ensure you capture all essential information about data collection, processing, and variables [14].

- Determine Data Access Level:

- Open Access: For fully anonymized, low-risk data.

- Controlled Access: For data requiring an agreement (DTA) and approval from a data access committee [16].

- Secure Analysis Environment: For highly sensitive data, where researchers can analyze but not download the data.

- Select a Repository and License: Choose a reputable repository that aligns with your field (e.g., Zenodo, Dryad) and assign a clear usage license to the dataset [14].

Research Reagent Solutions: Data Management & Consent Tools

The following table details key tools and frameworks essential for managing the ethical and legal aspects of research with large movement datasets.

| Item / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Consent Platform | A digital system (web or app-based) that allows research participants to review, manage, and withdraw their consent over time, enhancing engagement and ethical practice [15]. |

| Blockchain for Consent Tracking | Provides an immutable, decentralized ledger for recording patient consents and data-sharing preferences, creating a transparent and tamper-proof audit trail [21] [15]. |

| Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) | A digital identity model that gives individuals full control over their personal data and credentials, allowing them to manage consent for data sharing without relying on a central authority [15]. |

| FAIR Guiding Principles | A set of principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) to enhance the reuse of scientific data by making it more discoverable and usable by humans and machines [14]. |

| PETLP Framework | A Privacy-by-Design pipeline (Extract, Transform, Load, Present) for social media and AI research that can be adapted to manage the lifecycle of movement data responsibly [18]. |

| Data Transfer Agreement (DTA) | A legally binding contract that governs the transfer of data between organizations, specifying the purposes, security requirements, and use restrictions for the data [16]. |

| Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) | A process to systematically identify and mitigate privacy risks associated with a data processing project, as required by the GDPR for high-risk activities [18]. |

Establishing Standards for Metadata and Comprehensive Documentation

For researchers handling large movement datasets, establishing robust standards for metadata and documentation is not optional—it is a foundational requirement for data integrity, reproducibility, and regulatory compliance. High-quality documentation forms the bedrock upon which credible research is built, enabling the reconstruction and evaluation of the entire data lifecycle, from collection to analysis [22]. Adherence to these standards is critical for protecting subject rights and ensuring the safety and well-being of participants, particularly in clinical or sensitive research contexts [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the core principles of good documentation practice for research data? The ALCOA+ criteria provide a widely accepted framework for good documentation practice. Data and metadata should be Attributable (clear who documented the data), Legible (readable), Contemporaneous (documented in the correct time frame), Original (the first record), and Accurate (a true representation) [22]. These are often extended to include principles such as Complete, Consistent, Enduring (long-lasting), and Available [22].

2. What common pitfalls lead to documentation deficiencies in research? Systematic documentation issues often stem from a lack of training and understanding of basic Good Clinical Practice (GCP) principles [22]. Common findings include inadequate case histories, missing pages from subject records, unexplained corrections, discrepancies between source documents and case report forms, and failure to maintain records for the required timeframe [22].

3. What are Essential Documents in a regulatory context? Essential Documents are those which "individually and collectively permit evaluation of the conduct of a trial and the quality of the data produced" [23]. They demonstrate compliance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and all applicable regulatory requirements. A comprehensive list can be found in the ICH GCP guidance, section 8 [23].

4. How should documentation for a large, multi-layered movement dataset be structured? A comprehensive dataset should be organized into distinct but linkable components. A model dataset, such as the NetMob25 GPS-based mobility dataset, uses a structure with three complementary databases: an Individuals database (sociodemographic attributes), a Trips database (annotated displacements with metadata), and a Raw GPS Traces database (high-frequency location points) [24]. These are linked via a unique participant identifier.

5. What are key recommendations for sharing human movement data? Guidelines for sharing human movement data emphasize ensuring informed consent for data sharing, maintaining comprehensive metadata, using open data formats, and selecting appropriate repositories [25]. An extensive anonymization pipeline is also crucial to ensure compliance with regulations like the GDPR while preserving the data's analytical utility [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Data and Documentation Issues

| Issue Description | Potential Root Cause | Corrective & Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria cannot be confirmed [22] | Missing source documents (e.g., lab reports, incomplete checklists). | Implement a source document checklist prior to participant enrollment. Validate all criteria against original records. |

| Multiple conflicting records for the same data point [22] | Uncontrolled documentation creating uncertainty about the accurate source. | Define and enforce a single source of truth for each data point. Prohibit unofficial documentation. |

| Unexplained corrections to data [22] | Changes made without an audit trail, raising questions about data integrity. | Follow Good Documentation Practice (GDocP): draw a single line through the error, write the correction, date, and initial it. |

| Data transcription discrepancies [22] | Delays or errors in transferring data from source to a Case Report Form (CRF). | Implement timely data entry and independent, quality-controlled verification processes. |

| Inaccessible or lost source data [22] | Poor data management and storage practices (e.g., computer crash without backup). | Establish a robust, enduring data storage and backup plan from the study's inception. Use certified repositories [25]. |

Workflow for Documenting a Movement Dataset

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for establishing documentation standards, integrating principles from clinical research and modern movement data practices.

Data Presentation: Standards and Components

Quantitative Data from Exemplar Movement Dataset

The following table summarizes the scale and structure of a high-resolution movement dataset, as exemplified by the NetMob25 dataset for the Greater Paris region [24].

| Database Component | Record Count | Key Variables & Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals Database | 3,337 participants | Sociodemographic and household attributes (e.g., age, sex, residence, education, employment, car ownership). |

| Trips Database | ~80,697 validated trips | Annotated displacements with metadata: departure/arrival times, transport modes (including multimodal), trip purposes, and type of day (e.g., normal, strike, holiday). |

| Raw GPS Traces Database | ~500 million location points | High-frequency GPS points recorded every 2–3 seconds during movement over seven consecutive days. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Dedicated GPS Tracking Device (e.g., BT-Q1000XT) [24] | To capture high-frequency (2-3 second intervals), high-resolution ground-truth location data for movement analysis. |

| Digital/Paper Logbook [24] | To provide self-reported context and validation for passively collected GPS traces, recording trip purpose and mode. |

| Statistical Weighting Mechanism [24] | To infer population-level estimates from a sample, ensuring research findings are representative of the broader population. |

| Croissant Metadata Format [26] | A machine-readable format to document datasets, improving discoverability, accessibility, and interoperability. Required for submissions to the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks track. |

| Anonymization Pipeline [24] | A set of algorithmic processes applied to raw data (e.g., GPS traces) to ensure compliance with data protection regulations (like GDPR) while preserving analytical utility. |

Workflow for Resolving Documentation Issues

This troubleshooting diagram provides a logical pathway for identifying and correcting common documentation problems.

For researchers handling large movement datasets, data silos—isolated collections of data that prevent sharing between different departments, systems, and business units—represent a significant barrier to progress [27]. These silos can form due to organizational structure, where different teams use specialized tools; IT complexity, especially with legacy systems; or even company culture that views data as a departmental asset [27]. In the field of human movement analysis, this often manifests as disconnected data from various measurement systems (e.g., kinematics, kinetics, electromyography) trapped in incompatible formats and systems, hindering comprehensive analysis [14]. Overcoming these silos is essential for establishing a single source of truth, enabling data-driven decision-making, and unlocking the full potential of your research data [27].

FAQs

1. What is a data silo and why are they particularly problematic for movement data research?

A data silo is an isolated collection of data that prevents data sharing between different departments, systems, and business units [27]. In movement research, they are problematic because they force researchers to work with outdated, fragmented datasets [27]. This is especially critical when trying to integrate data from different measurement systems (e.g., combining kinematic, kinetic, and EMG data), as a lack of comprehensive standards can prevent adherence to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles, ultimately compromising the transparency and reproducibility of your research [14].

2. What are the common signs that our research group is suffering from data silos?

Common signs include [28]:

- Different team members or labs define the same key metrics in different ways.

- Significant manual effort is required to reconcile or combine datasets for analysis.

- Reports or results generated from different systems don't match.

- Researchers regularly ask "Where can I find this dataset?" or repeatedly request the same data in slightly different formats.

- Every new analysis requires a custom data integration effort or IT ticket.

- There is low confidence in the accuracy, recency, or context of the available data.

3. We have the data, but it's stored in different formats and software. What is the first step to unifying it?

The critical first step is discovery and inventory [29]. You must systematically catalog everything that generates, stores, or processes data—including all software applications (e.g., Vicon Nexus, Matlab, R), cloud storage, and even shadow IT tools used by individual team members [29]. For each dataset, document the data owner, who contributes or consumes it, and the data formats used (e.g., c3d files for motion capture) [29] [14]. This process builds a complete inventory of datasets, their interactions, and their users.

4. How can we ensure our unified movement data remains trustworthy and secure?

Implementing data governance protocols is essential [29]. This includes:

- Automated Data Quality Checks: Use tools like dbt tests or build validation features into your data warehouse to flag issues like schema changes or missing values before they affect analyses [29].

- Role-Based Access Controls (RBAC): Limit access to sensitive data (e.g., patient-identifiable information) based on user roles. For example, a clinical support team might view a record with specific details redacted, while the principal investigator sees the full record [29].

- Metadata and Lineage Tracking: Maintain comprehensive metadata and audit usage patterns to understand how often data is refreshed and document the lineage of a dataset between tools and processes [29].

5. What are the key metrics to track to know if our efforts to break down silos are working?

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for this initiative include [29]:

- Monthly Pipeline Maintenance Hours: A decrease in hours spent on maintenance shows time and cost savings on engineering overhead.

- Data Freshness Lag: The time between updates to source data and when it becomes available for analysis. Lower lags indicate healthier pipelines and faster reporting cycles.

- Data Quality Scores: Metrics on data completeness, accuracy, and consistency.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating Data Silo Reduction Efforts

| KPI | Description | Target Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Pipeline Maintenance Hours | Hours spent monthly on maintaining data pipelines | Decrease over time |

| Data Freshness Lag | Time delay between data creation and availability | Minimize lag |

| Data Quality Score | Score based on completeness, accuracy, consistency | Increase score |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Data Definitions Across Labs

Symptoms: The same term (e.g., "gait cycle duration") is defined or calculated differently by various researchers or labs, leading to irreconcilable results.

Solution:

- Establish a Semantic Layer: Create a shared data dictionary or semantic layer that enforces consistent definitions for all key metrics and terms across your research projects [28].

- Define Standard Protocols: Before starting multi-site studies, agree upon and document standard data collection and processing protocols. The guidelines developed for human movement analysis, which include recommendations for metadata and open formats, can serve as an excellent template [14].

- Implement Governance: Assign data stewards to oversee the adherence to these defined standards and definitions [27].

Problem: Manual, Time-Consuming Data Integration

Symptoms: Researchers spend excessive time manually extracting data from specialized software (e.g., Vicon Nexus) and converting it for analysis in tools like R or Python, often using error-prone scripts.

Solution:

- Automate ELT Processes: Replace manual scripts with automated Extract, Load, Transform (ELT) pipelines. Modern managed connectors can automate data extraction from various sources and handle schema changes automatically, reducing engineering overhead [29].

- Centralize in a Data Warehouse/Lakehouse: Load data from all sources into a central repository, such as a data lakehouse, which combines the scale of data lakes with the governance of data warehouses [30]. This creates a single source of truth.

- Utilize ETL Tools: Leverage ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) tools to build pipelines that standardize and move data from existing silos into your centralized location, maintaining ongoing quality control [30].

Problem: Legacy System Data is Inaccessible

Symptoms: Valuable historical data is locked in outdated databases or file formats that cannot easily connect to modern analysis tools.

Solution:

- Data Virtualization: Use data virtualization tools to create a unified view of the data without physically moving it from its original source, providing immediate access [27].

- API Integration: Build a series of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and connectors to enable secure, real-time data access between legacy and modern systems [27].

- Phased Migration: Develop a plan to gradually migrate the most critical historical datasets to your modern, centralized data platform using ETL processes [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: A Methodology for Analyzing Large-Scale Human Mobility Data

The following protocol is adapted from a study that utilized human mobility data from over 20 million individuals to investigate determinants of physical activity [31]. This provides a robust framework for handling massive, complex movement datasets.

Objective: To analyze visits to various location categories and investigate how these visits influence same-day fitness center attendance [31].

Dataset:

- Source: Utilize a "Visits" dataset (e.g., from providers like Veraset) comprising anonymized records from millions of devices, capturing places individuals visited at specific dates and times [31].

- Data Points: Each record should include a user identifier, timestamp, location name, location category/subcategory, and minimum duration of visit [31].

- Focus Subcategory: For physical activity research, focus on the subcategory "Fitness and Recreational Sports Centers" within the broader top category of "Other Amusement and Recreation Industries" [31].

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Convert all timestamps to the user's local time to accurately assign visits to calendar days [31].

- User Classification: Identify "exercisers" as users with recorded visits to fitness centers over the observation period. The remaining users are classified as "non-exercisers" for comparative analysis [31].

- Regression Analysis: Implement an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression framework to quantify how visits to various location categories influence same-day fitness visits. Control for potential biases, such as the user's state and the day of the week [31].

- Comparative Analysis: On days when exercisers do not visit a fitness center ("rest days"), calculate descriptive statistics for their visits to other categories. Compare these patterns with the visit patterns of non-exercisers on the same days [31].

- Temporal Analysis: For exercisers, analyze the sequence of visits on days they exercised. Aggregate data to determine which location categories are predominantly visited immediately before or after a fitness session [31].

Table 2: Key Software and Tools for Movement Data Integration

| Tool Category | Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Automated ELT/ETL | Fivetran, custom pipelines | Automates extraction from sources (e.g., lab software) and loading into a central warehouse [29] [30]. |

| Data Warehouse/Lakehouse | Databricks, IBM watsonx.data | Serves as a centralized, governed repository for all structured and unstructured research data [27] [30]. |

| Data Transformation | dbt | Applies transformation logic and data quality tests within the warehouse to ensure clean, analysis-ready data [29]. |

| Analytics & BI | Looker, R, Python | Provides self-service analytics and visualization on top of the unified data platform [29]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential "Reagents" for Data Integration Experiments

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Managed Data Connectors | Pre-built connectors that automatically extract data from specific source systems (e.g., lab equipment software, clinical databases) while handling schema changes and API updates [29]. |

| Open Data Formats | Non-proprietary file and table formats (e.g., Parquet, Delta Lake, Apache Iceberg) that ensure long-term data readability and interoperability between different analysis tools, preventing future silos [30]. |

| Metadata Templates | Standardized templates for documenting critical information about a dataset (e.g., participant demographics, collection parameters, processing steps), as promoted by open data guidelines in human movement analysis [14]. |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Tools, including those powered by generative AI, that create artificial datasets mirroring the statistical properties of real data. Useful for augmenting small datasets or testing pipelines without using sensitive, real patient data [32]. |

| Vector Databases | Databases (e.g., Pinecone, Weaviate) optimized for storing and retrieving high-dimensional vector data, which is crucial for efficient similarity search in large datasets, such as those used for AI model training [32]. |

Visualizations

Data Integration Workflow for Movement Analysis

Research Data Lifecycle

This diagram outlines the key stages of the research data lifecycle, from planning to sharing, as informed by guidelines developed for human movement analysis [14].

Advanced Methods for Processing and Analyzing Movement Data

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common data quality issues in raw movement data? Raw movement data often contains missing values from sensor dropouts, duplicate records from transmission errors, incorrect data types (e.g., timestamps stored as text), and outliers from sensor malfunctions or environmental interference. Addressing these is the first step in the wrangling process [33].

How can I handle missing GPS coordinates in a time-series tracking dataset? The strategy depends on the data's nature. For short, intermittent gaps, linear interpolation between known points is often sufficient. For larger gaps, machine learning techniques like k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation can predict missing values based on similar movement patterns in your dataset. AI-powered data cleaning tools are increasingly capable of automating this by learning from historical patterns to suggest optimal fixes [33].

What tools are best for cleaning and transforming large-scale movement data? The choice of tool depends on the data volume and your team's technical expertise.

- For large datasets: Apache Spark is designed for distributed processing of massive data volumes across computer clusters, making it suitable for high-frequency movement data [34] [35]. Python with libraries like Polars offers a fast and scalable alternative to traditional tools for cleaning huge datasets [36].

- For automated and AI-driven cleaning: Platforms like Mammoth Analytics and DataPure AI use machine learning to automatically detect anomalies, correct inconsistencies, and standardize data with minimal manual effort [33].

- For visual, low-code workflows: KNIME and RapidMiner allow you to build data cleaning and transformation workflows using a drag-and-drop interface, which is accessible for researchers without a deep programming background [35].

How do I ensure my processed movement data is reproducible? Reproducibility is a cornerstone of good science. To achieve it:

- Use Scripted Workflows: Prefer tools like Python scripts or Jupyter Notebooks over manual, point-and-click cleaning. These scripts document every step of your process [35].

- Version Control: Store your data cleaning and analysis code in a version control system like Git.

- Automated Validation: Use data validation frameworks like Great Expectations to define and automatically check data quality rules (e.g., "all latitudes must be between -90 and 90") at each processing stage [36].

My visualizations are hard to read. How can I make them more accessible? Accessible visualizations ensure your research is understood by all audiences.

- Color Contrast: Ensure text and graphical elements have a sufficient contrast ratio against their background. For standard text, aim for at least a 4.5:1 ratio, and for large text, at least 3:1 [37] [38]. Use tools like ColorBrewer and Viz Palette to choose accessible, colorblind-safe palettes [39].

- Don't Rely on Color Alone: Use additional visual indicators like different shapes, patterns, or direct data labels to convey information. This helps individuals with color vision deficiencies [37].

- Provide Text Descriptions: Always include alt text for images of charts and consider providing a supplemental data table to make the underlying data accessible [37] [39].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Sensor drift leads to a gradual loss of accuracy in movement measurements over time.

- Solution: Implement a calibration protocol. Periodically collect data from a known, fixed position or during a standardized movement task. Use this data to model the drift and apply a correction factor to your dataset. For high-frequency data, tools like Apache Flink can handle real-time correction on streaming data [36].

Problem: Inconsistent sampling rates after merging data from multiple devices.

- Solution: Resample all data streams to a common frequency. You can either upsample (increase frequency) or downsample (decrease frequency) the data. A common method is to interpolate the data to a uniform timestamp grid. Python's Pandas library has robust functions for resampling time-series data [36].

Problem: Identifying and filtering out non-movement or rest periods from continuous data.

- Solution: Develop a threshold-based algorithm. Calculate a movement metric (e.g., velocity, acceleration magnitude) for each time window. Data points where the metric falls below a empirically determined threshold for a sustained period can be classified as non-movement. Machine learning platforms like RapidMiner can help build and validate more complex classification models for this task without extensive coding [35].

Problem: Data from different sources (e.g., lab sensors, wearable devices) use conflicting formats and units.

- Solution: Create a standardized data transformation pipeline. Use a tool like dbt or a visual ETL platform to define rules for converting all data into a common schema and set of units (e.g., converting feet to meters, local time to UTC) before analysis. Cloud-based platforms are excellent for managing these complex, multi-source integrations [33].

Research Reagent Solutions: The Data Wrangler's Toolkit

The following table details key software and libraries essential for cleaning and preparing movement data.

| Tool/Library | Primary Function | Key Features for Movement Data |

|---|---|---|

| Python (Pandas) [35] | Data manipulation and analysis | Core library for data frames; ideal for structured data operations like filtering, transforming, and aggregating time-series data [35]. |

| Apache Spark [34] [35] | Distributed data processing | Enables large-scale data cleaning and transformation across clusters for datasets too big for a single machine [34] [35]. |

| Great Expectations [36] | Data validation and testing | Defines "expectations" for data quality (e.g., non-null values, allowed ranges), automatically validating data at each pipeline stage [36]. |

| KNIME [35] | Visual data workflow automation | Low-code, drag-and-drop interface for building reusable data cleaning protocols, accessible to non-programmers [35]. |

| Mammoth Analytics [33] | AI-powered data cleaning | Uses machine learning to automate anomaly detection, standardization, and transformation, learning from user corrections [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Movement Data Wrangling

This protocol outlines a standardized methodology for cleaning raw movement data, ensuring consistency and reproducibility in research.

1. Data Acquisition and Initial Assessment

- Objective: To import raw data and perform an initial quality check.

- Procedure:

- Import data from source files (e.g., CSV, JSON) or streaming sources (e.g., Kafka) into your analysis environment.

- Use data profiling tools (e.g., Pandas Profiling, Great Expectations) to generate a summary report. This report should highlight the count of missing values, data types, and basic descriptive statistics [36].

- Visually inspect a sample of the raw data using simple plots (e.g., line plots of coordinates over time) to identify obvious anomalies or patterns of sensor failure.

2. Data Cleaning and Transformation

- Objective: To correct errors, handle missing data, and standardize formats.

- Procedure:

- Handle Missing Data: Based on the assessment from Step 1, choose and apply a strategy. For movement data, this could be deletion, interpolation, or imputation using AI-powered tools [33].

- Remove Duplicates: Identify and remove exactly identical records.

- Correct Data Types: Ensure columns are correctly typed (e.g., datetime objects for timestamps, numeric types for coordinates).

- Standardize Values: Convert all units to a consistent system (e.g., meters, seconds).

- Filter Outliers: Use statistical methods (e.g., Z-scores, IQR) or domain knowledge to identify and handle unrealistic data points.

3. Data Validation and Documentation

- Objective: To ensure the cleaned data meets quality standards and the process is documented.

- Procedure:

- Run the cleaned dataset against the validation rules defined in Great Expectations to confirm all checks pass [36].

- In a Jupyter Notebook [35] or script, document all cleaning steps, including parameters for imputation and thresholds for outlier removal. The final output is a clean, analysis-ready dataset and a complete record of the wrangling process.

The following table categorizes and quantifies typical anomalies found in raw movement datasets, which can be used to benchmark data quality efforts.

| Anomaly Type | Description | Example in Movement Data | Typical Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data [33] | Gaps in the data stream. | Sensor fails to record location for 5-minute intervals. | Skews travel time calculations and disrupts path continuity. |

| Outliers [33] | Data points that deviate significantly from the pattern. | A single GPS coordinate places the subject 1 km away from a continuous path. | Distorts measures of central tendency and can corrupt spatial analysis. |

| Duplicate Records [33] | Identical entries inserted multiple times. | The same accelerometer reading is logged twice due to a software bug. | Inflates event counts and misrepresents the duration of activities. |

| Inconsistent Formatting [33] | Non-uniform data representation. | Timestamps in mixed formats (e.g., MM/DD/YYYY and DD-MM-YYYY). |

Causes errors during time-series analysis and data merging. |

Data Wrangling Workflow for Movement Data

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow and decision points involved in preparing raw movement data for analysis.

Troubleshooting Logic for Data Quality Issues

This diagram provides a structured decision tree for diagnosing and resolving common problems encountered during the data wrangling process.

Leveraging ETL and ELT Pipelines for Efficient Data Movement and Integration

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Failure Diagnosis and Resolution

Problem: My data pipeline has failed silently. How do I begin to diagnose the issue?

Solution: Follow this systematic, phase-based approach to identify and resolve the failure point [40].

Step 1: Identify the Failure Point Check your pipeline’s monitoring and alerting system to pinpoint where the job failed [40].

- Check Logs: Review job execution logs from your orchestration framework or ETL tool. Work backward from the failure timestamp to find the last successful step [40].

- Examine Alerts: Review any alert messages, which often contain error codes or the name of the table/file that caused the problem [40].

- Review System Health: Check the CPU, memory, and disk space of your source database, data warehouse, and ETL runtime environment [40].

Step 2: Isolate the Issue Determine in which phase the failure occurred [40].

| Failure Phase | Common Error Indicators |

|---|---|

| Extraction (E) | Connection issues, API rate limits, "file not found" errors [40]. |

| Transformation (T) | Data type mismatches, bad syntax in SQL/queries, null value handling errors [40]. |

| Loading (L) | Primary key or unique constraint violations, connection timeouts on the target system [40]. |

Step 3: Diagnose Root Cause Once isolated, investigate the specific cause [40].

- For Schema Drift: Query the source system's schema and compare it to the expected schema defined in your transformation code [40].

- For Data Mismatch: Run the transformation logic on a small subset of the failing data in a staging environment to reproduce the error [40].

- For Performance/Volume: Review historical performance metrics to identify sudden data volume spikes or data warehouse scaling issues [40].

Step 4: Apply Fixes and Re-Test Apply the fix in a staging environment before reprocessing the failing data [40].

- Extraction Fix: Update credentials, handle new schema, implement retry logic for API throttling [40].

- Transformation Fix: Correct SQL/code logic, implement robust null-handling (e.g.,

COALESCE), quarantine records that fail validation [40]. - Loading Fix: If safe, drop and recreate the table; temporarily disable constraints for the load; optimize bulk load configuration [40].

Handling Schema Changes in Source Data

Problem: An upstream data source changed a column name, causing my pipeline to break.

Solution: Implement proactive schema management and resilience.

- Automated Schema Detection: Use tools that automatically detect source schema changes (e.g., new columns, renamed fields, type changes) and adjust the destination schema without manual intervention [40] [41].

- Adopt Flexible Schemas: Utilize data warehouses that support semi-structured data (like JSON) or implement schema evolution practices to handle minor changes gracefully [40].

- Decouple Load and Transform: Design your pipeline so that ingestion and transformation are separate. This ensures that even if a transformation fails due to a schema change, raw data continues to load, maintaining data availability while you fix the transformation logic [41].

Managing Sudden Spikes in Data Volume

Problem: My pipeline is being overwhelmed by a sudden, unexpected surge in data volume.

Solution: Optimize for scalability and efficient processing.

- Leverage Cloud Scalability: ELT architectures are advantageous here, as they utilize the native scaling capabilities of modern cloud data warehouses (e.g., Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift) to handle processing load [42] [43].

- Implement Incremental Loading: Instead of reloading the entire dataset every time, use an incremental data loading strategy. This approach only processes new or changed data, significantly reducing load times and resource consumption [44].

- Architect for Performance: Use platforms with streaming architectures that can handle high concurrency and large data volumes with minimal memory overhead, preventing performance bottlenecks [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between ETL and ELT, and which should I use for large-scale research data?

A: The core difference lies in the order of operations and the location of the transformation step [42] [43].

- ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) transforms data on a separate processing server before loading it into the target data warehouse. This is often better for highly structured environments with strict data governance and pre-defined schemas, or when data requires heavy cleansing before entering the warehouse [42] [45].

- ELT (Extract, Load, Transform) loads raw data directly into the target data warehouse and performs transformations inside the warehouse itself. This is the modern approach for large-scale data, as it leverages the power of cloud data warehouses, offers greater flexibility, and is more scalable and cost-efficient for big data and unstructured data [42] [45] [43].

For large movement datasets in research, ELT is generally recommended due to its scalability, flexibility for iterative analysis, and ability to preserve raw data for future re-querying [42] [43].

Q2: How can I validate that my ETL/ELT process is accurately moving data without corruption?

A: Implement a rigorous validation protocol, as used in clinical data warehousing [46].

- Random Sampling: Randomly select a subset of patients (or data subjects) and specific observations from your data warehouse [46].

- Gold Standard Comparison: Compare these selected data points against the original source systems (the "gold standard") [46].

- Categorize and Resolve Discordances: Investigate and categorize any discrepancies. Common causes include:

- Design Decisions: ETL/ELT rules that intentionally exclude or modify certain data.

- Timing Issues: Differences between the time of data extraction and the current state of the source.

- User Interface Settings: Display or security settings in the source system that affect data visibility [46]. This process ensures the correctness of the data movement process and helps identify specific areas for improvement.

Q3: What are the most common causes of data quality issues in pipelines, and how can I prevent them?

A: Common causes and their preventive solutions are summarized in the table below [40] [44] [47].

| Cause | Description | Preventive Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Schema Drift | Upstream source changes a column name, data type, or removes a field without warning [40]. | Implement automated schema monitoring and evolution [40] [41]. |

| Data Source Errors | Missing files, API rate limits, connection failures, or source system unavailability [40]. | Implement robust connection management and retry mechanisms with exponential backoff [40] [41]. |

| Poor Data Quality | Source data contains NULLs, duplicates, or violates business rules [40] [44]. | Use data quality tools for profiling, cleansing, and validation at multiple stages of the pipeline (e.g., post-extraction, pre-load) [40] [47]. |

| Transformation Logic Errors | Bugs in SQL queries or transformation code (e.g., division by zero, incorrect joins) [40]. | Implement comprehensive testing and version control for all transformation code. Use a CI/CD pipeline to promote changes safely [45]. |

Q4: My data transformations are running too slowly. What optimization strategies can I employ?

A: Consider the following strategies:

- Leverage In-Database Processing: If using ELT, ensure transformations are performed within the data warehouse to take advantage of its distributed computing power [42] [43].

- Optimize Query Logic: Review and refine transformation SQL for efficiency (e.g., avoid unnecessary joins, use selective filters).

- Implement Incremental Models: Instead of transforming entire datasets each time, build transformations to process only new or updated records [45].

Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Validation

Protocol: Validating ETL/ELT Correctness for a Clinical Data Warehouse

This protocol is adapted from a peer-reviewed study validating an Integrated Data Repository [46].

1. Objective To validate the correctness of the ETL/ELT process by comparing a random sample of data in the target data warehouse against the original source systems.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Source Systems: The original operational databases (e.g., Electronic Health Record systems like EpicCare) [46].

- Target System: The destination clinical data warehouse or research database (e.g., an i2b2 platform) [46].

- Validation Tooling: Access to query both source and target databases; a data validation framework or scripting language (e.g., Python, SQL).

3. Methodology

- Step 1: Random Sampling. Use a database random function to select a statistically significant number of unique subjects (e.g., 100 patients). From these, randomly select multiple observations per subject (e.g., 5 per patient) across different data types (e.g., laboratory results, medications, diagnoses) [46].

- Step 2: Data Extraction. For each selected observation, programmatically extract the value from both the target data warehouse and the corresponding value from the source system.

- Step 3: Comparison and Reconciliation. Perform an automated comparison of the two values for each observation. Categorize comparisons as "concordant" (matching) or "discordant" (non-matching) [46].

- Step 4: Discordance Analysis. Manually investigate each discordance to determine the root cause. Categories typically include:

- Design/Tooling Difference: A known and intentional transformation in the ETL/ELT logic.

- Timing Issue: A discrepancy caused by the data being updated in the source after the last ETL/ELT run.

- Genuine Error: An unidentified error in the extraction, transformation, or loading logic [46].

- Step 5: Calculation of Accuracy Metric. Calculate the accuracy as (Number of Concordant Observations / Total Number of Observations) * 100. After resolving known design differences, the effective accuracy should approach 100% [46].

4. Expected Outcome A quantitative measure of data movement accuracy (e.g., >99.9%) and a log of all discordances with their root causes, providing a foundation for process improvements.

Workflow Diagram: ETL/ELT Correctness Validation

The following diagram illustrates the validation protocol workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key "reagents" – the tools and technologies – essential for building and maintaining robust data pipelines in a research context.

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics for Research |

|---|---|---|

| dbt (Data Build Tool) | Serves as the transformation layer in an ELT workflow; enables version control, testing, documentation, and modular code for data transformations [42] [45]. | Promotes reproducibility and collaboration—critical for scientific research. Allows researchers to define and share data cleaning and feature engineering steps as code. |

| Cloud Data Warehouse (e.g., Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift) | The target destination for data in an ELT process; provides the scalable compute power to transform large datasets in-place [42] [43]. | Essential for handling large-scale movement datasets. Offers on-demand scalability, allowing researchers to analyze vast datasets without managing physical hardware. |

| Hevo Data / Extract / Rivery | Automated data pipeline platforms that handle extraction and loading from numerous sources (APIs, databases) into a data warehouse [40] [41] [48]. | Reduces the operational burden on researchers. Manages connector reliability, schema drift, and error handling automatically, freeing up time for data analysis. |

| Talend Data Fabric | A unified platform that provides data integration, quality, and governance capabilities for both ETL and ELT processes [47] [48]. | Useful in regulated research environments (e.g., drug development) where data lineage, profiling, and quality are paramount for compliance and auditability. |

| Data Quality & Observability Tools | Monitor data health in production, detecting anomalies in freshness, volume, schema, and quality that could compromise research findings [40]. | Provides continuous validation of input data, helping to ensure that analytical models and research conclusions are based on reliable and timely data. |

Machine Learning and AI Models for Movement Detection and Analysis (e.g., CNN, LSTM, Random Forest)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My CNN model for activity recognition is overfitting to the training data. What are the most effective regularization strategies?

A1: CNNs are prone to overfitting, especially with complex data like movement sequences. Several strategies can help [49] [50]:

- Pooling Layers: Integrate max-pooling layers into your architecture. These layers reduce the spatial dimensions (height, width) of the feature maps, providing translation invariance and lowering the risk of overfitting by reducing the number of parameters [49] [50].

- Dropout: This technique randomly "drops out," or ignores, a percentage of neurons during training, preventing the network from becoming overly reliant on any single neuron and forcing it to learn more robust features [49].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training dataset by creating modified versions of your existing movement data. For temporal sequences, this can include adding noise, slightly warping the time series, or cropping segments [51].

Q2: How do I choose between a CNN, LSTM, or a combination of both for time-series movement data?

A2: The choice depends on the nature of the movement data and the task [50] [52]:

- CNN: Ideal for identifying local, spatially-invariant patterns within a short time window. Use a 1D CNN if your movement data is a feature vector per time step (e.g., accelerometer readings). It excels at extracting robust, translation-invariant features from the input sequence [49] [50].

- LSTM: Designed to model long-range dependencies and temporal dynamics in sequential data. Choose an LSTM if the context and order of movements over a long period are critical for your classification task (e.g., distinguishing between similar movements based on their sequence).

- CNN-LSTM Hybrid: This architecture leverages the strengths of both. The CNN layer first acts as a feature extractor on short time segments, and the LSTM layer then models the temporal relationships between the extracted feature sequences. This is often the most powerful approach for complex movement analysis [53].

Q3: What are the primary challenges when working with large-scale, graph-based movement data, and how can GNNs address them?

A3: Movement data can be represented as graphs where nodes are locations or entities, and edges represent the movements or interactions between them. Traditional ML models struggle with this non-Euclidean data [54] [52].

- Challenges:

- Variable Size and Topology: Graphs have an arbitrary number of nodes with complex connections, unlike fixed-size images or text [52].

- No Spatial Locality: There is no fixed grid structure, making operations like convolution difficult to define [52].

- Node Order Invariance: The model's output should not change if the nodes are relabeled [52].

- GNN Solutions: GNNs learn node embeddings by aggregating feature information from a node's local network neighborhood. This is done through message passing, where each node computes a new representation based on its own features and the features of its neighbors. This allows GNNs to naturally handle the graph structure for tasks like node classification (e.g., classifying locations) or link prediction (e.g., predicting future movement between points) [54] [52].

Q4: My model's performance is strong on training data but drops significantly on the test set, suggesting overfitting. What is my systematic troubleshooting protocol?

A4: Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Verify Data Integrity: Ensure there is no data leakage between your training and test sets. Check that all data preprocessing steps (normalization, imputation) are fit only on the training data.

- Simplify the Model:

- Reduce model complexity (e.g., fewer layers, fewer neurons).

- Increase regularization (e.g., higher dropout rate, L2 regularization).

- If using tree-based models like Random Forest, reduce maximum depth or increase the minimum samples required to split a node.

- Augment Training Data: If possible, use data augmentation techniques specific to your movement data to increase the size and diversity of your training set [51].

- Implement Early Stopping: Monitor the model's performance on a validation set during training and halt training when performance begins to degrade.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Vanishing Gradients in Deep Networks for Long Movement Sequences

Symptoms:

- Model loss fails to decrease or does so very slowly.

- Model weights in earlier layers show minimal updates.

- Poor performance on tasks requiring long-term context.

Resolution Steps:

- Architecture Selection: Replace standard RNNs with LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) or GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) networks. These architectures contain gating mechanisms that help preserve gradient flow through many time steps.

- Activation Functions: Use activation functions that are less susceptible to vanishing gradients, such as ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) or its variants (Leaky ReLU) in CNNs and feed-forward networks [49].

- Batch Normalization: Incorporate batch normalization layers within your network. This technique normalizes the inputs to each layer, stabilizing and often accelerating training.

- Residual Connections: Utilize architectures that feature residual (or skip) connections. These connections allow the gradient to flow directly through the network, mitigating the vanishing gradient problem in very deep networks.

Issue: Poor Generalization of Models to Real-World Movement Data After Strong Lab Performance

Symptoms:

- High accuracy on clean, lab-collected data but poor performance on noisy, real-world data.

- Model fails when encountering movement patterns or subjects not represented in the training set.

Resolution Steps:

- Analyze Dataset Bias: Scrutinize your training data for representation gaps (e.g., limited demographic variety, specific environmental conditions). The NetMob25 dataset, for example, highlights the importance of multi-dimensional individual-level data (sociodemographic, household) to understand such biases [55].

- Data Augmentation: Introduce realistic noise, sensor dropouts, and transformations that mimic real-world conditions into your training data [51].

- Domain Adaptation Techniques: Explore techniques designed to align the feature distributions of your lab (source domain) and real-world (target domain) data.

- Leverage Federated Learning: If data from multiple real-world sources is available but cannot be centralized (e.g., due to privacy in healthcare), consider federated learning. This privacy-preserving technique allows for collaborative model training across multiple decentralized devices or servers holding local data samples without exchanging them [56].

The following tables summarize key quantitative metrics for various models applied to different movement analysis tasks, based on cited research.

Table 1: Model Comparison for Human Activity Recognition (HAR)

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score | Computational Cost (GPU VRAM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|