Minimizing Impact: Advanced Strategies for Reducing Animal-Borne Telemetry Tag Effects on Wildlife and Data

Animal-borne telemetry is a pivotal tool for ecological and physiological research, yet the tags themselves can alter animal behavior, energetics, and welfare, thereby compromising data validity.

Minimizing Impact: Advanced Strategies for Reducing Animal-Borne Telemetry Tag Effects on Wildlife and Data

Abstract

Animal-borne telemetry is a pivotal tool for ecological and physiological research, yet the tags themselves can alter animal behavior, energetics, and welfare, thereby compromising data validity. This article synthesizes the latest methodologies for quantifying and mitigating tag impacts, drawing on recent peer-reviewed studies. We explore a multidisciplinary approach that combines Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for hydrodynamic optimization, novel tag attachment techniques like drone deployment, and the development of interoperable open protocols. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review provides a foundational understanding of tag-induced effects, offers practical guidelines for tag selection and attachment, discusses troubleshooting for common field challenges, and validates approaches through case studies and performance comparisons. The conclusions outline future directions for creating minimally invasive, high-fidelity biologging systems that enhance both animal welfare and data reliability.

Understanding the Burden: Quantifying the Hydrodynamic and Behavioral Impacts of Animal-Borne Tags

Troubleshooting Guides

Tag-Induced Behavioral Changes

Observed Problem: The collected data shows a significant reduction in foraging activity and changes in dive profiles for 2-3 weeks post-tagging.

Diagnosis: This is a common short-term effect of tag implantation. Research on Northern sea otters has demonstrated that animals experience a period of altered behavior and physiological response following surgery [1].

Solution:

- Pre-planning: Design your study to account for a post-implantation recovery and acclimation period. Data collected during this time should be analyzed separately or excluded from baseline behavior analysis.

- Establish Baseline: Use pre-implantation observations or data from the recovery period's end to establish a reliable baseline for comparison.

- Quantify Recovery: Implement a breakpoint analysis to identify when behavior and physiology stabilize. In sea otters, body temperature returned to baseline in approximately 15 days, while behavioral metrics stabilized around 18 days post-implantation [1].

Data Not Received or Signal Lost

Observed Problem: The telemetry system is not receiving data from the implanted tag.

Solution:

- Verify Receiver Function: Ensure the external receiver is operational, correctly configured, and within the expected transmission range.

- Check Animal Vital Signs: Confirm the animal's status. In preclinical research, continuous monitoring of vital signs like ECG and activity can help distinguish device failure from animal mortality [2].

- Inspect Internal Logs: Review the system's internal telemetry and logs for errors, which can indicate communication failures or hardware issues [3] [4].

Data Shows High Variability or Artifacts

Observed Problem: The physiological data (e.g., ECG, body temperature) is noisy and inconsistent, making it difficult to interpret.

Diagnosis: This can be caused by post-surgical inflammation, animal stress, or tag malfunction.

Solution:

- Identify Source: Correlate data streams. A concurrent, sustained increase in body temperature can indicate an inflammatory response to the tag, as seen in sea otters, rather than a device error [1].

- Monitor Recovery: Allow time for the animal to recover from surgery. Data quality often improves as inflammation subsides and the animal acclimates.

- Review Surgical Protocol: Ensure aseptic surgical techniques and proper tag placement to minimize tissue reaction and movement artifacts [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical recovery timeline for an animal after tag implantation? A1: Recovery is species-specific and depends on the procedure's invasiveness. A study on Northern sea otters found that body temperature elevated due to immune response returned to baseline after about 15 days, and normal dive behavior resumed after about 18 days [1]. Researchers should use a breakpoint analysis on their own data to determine the precise acclimation period for their study species.

Q2: How can I minimize the impact of tagging on my study animals? A2: Key strategies include:

- Refine Surgical Techniques: Use experienced surgical teams and follow aseptic protocols to reduce infection risk and promote healing [2].

- Optimize Tag Size: Select the smallest and lightest tag possible relative to the animal's body mass to minimize energetic costs and physical burden.

- Allow for Acclimation: Incorporate a post-surgery acclimation period before starting experimental treatments or baseline data collection.

- Use Advanced Methods: Consider magnetometry techniques, where a small magnet and sensor can monitor specific behaviors with less intrusive hardware [5].

Q3: Are there ethical considerations and potential welfare issues I should be aware of? A3: Yes. The core ethical principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement (3Rs) are paramount [2].

- Refinement: Telemetry itself is a refinement as it reduces the need for repeated handling. However, the implantation surgery and the tag's presence are potential stressors.

- Welfare Monitoring: Protocols must include post-operative analgesia and meticulous monitoring for signs of pain, infection, or impaired behavior.

- Electromagnetic Fields (EMF): Some research suggests potential physiological effects from the electromagnetic fields emitted by tags, as many species are sensitive to man-made EMFs. This is an emerging area of concern that requires consideration [6].

Q4: My data isn't showing up in the analysis system. What should I check? A4: Follow a systematic troubleshooting approach [3] [4]:

- Check Connectivity: Verify the network connection between the data collector and your analysis database or server.

- Review Logs: Examine the system's internal logs for error messages related to data processing or export failures.

- Verify Configuration: Ensure all data pipelines, receivers, and exporters are correctly defined and enabled in the system configuration.

Quantitative Data on Tag Effects

The following table summarizes empirical data on the short-term effects of intra-abdominal tag implantation in Northern sea otters, providing a benchmark for expected recovery metrics [1].

Table 1: Short-Term Recovery Metrics from Sea Otter Tag Implantation Study

| Parameter | Pre-Breakpoint Condition | Observed Change (Δ) | Time to Return to Baseline (Days, Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature (Tb) | Baseline | Increased by 0.46°C | 14.61 ± 5.19 |

| Dive Behavior | Normal foraging effort | Reduced foraging dives, shorter bouts, longer intervals between bouts | 17.96 ± 1.9 |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Short-Term Tag Impacts

Objective: To quantitatively determine the recovery timeline of an animal's physiology and behavior following telemetry tag implantation.

Methodology:

- Pre-implantation Baseline: Record baseline behavioral and physiological data whenever possible.

- Tag Implantation: Perform the surgical or attachment procedure following strict aseptic protocols and best practices for the species.

- Continuous Data Collection: Post-implantation, continuously archive data for key metrics such as:

- Core body temperature

- Dive behavior (for marine species): number of dives, dive duration, time between dives

- Activity levels (e.g., from accelerometers)

- Heart rate (if available)

- Breakpoint Analysis: Retrospectively analyze the archived data stream to identify statistically significant breakpoints where the measured metrics stabilize. This identifies the end of the recovery period.

- Statistical Modeling: Use linear mixed-effect models to determine if the recovery timeline is influenced by covariates such as sex, age, reproductive status, or implant location [1].

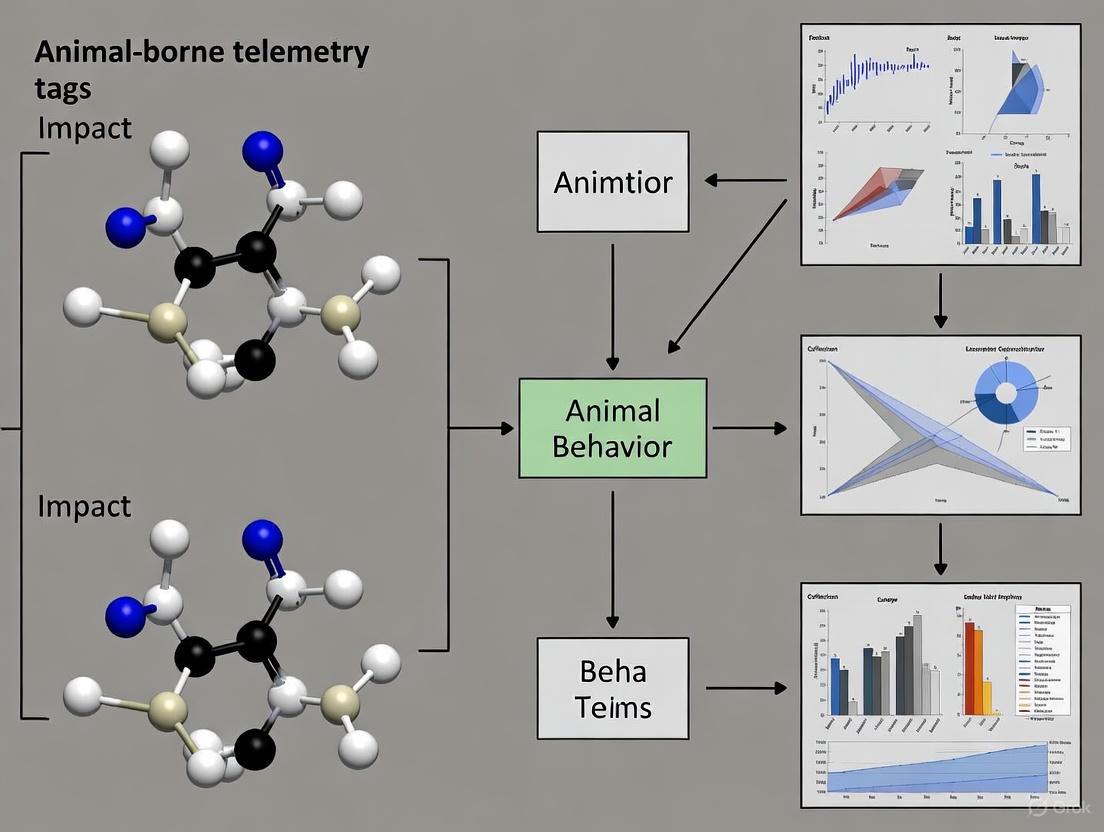

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Telemetry Impact Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Implantable Telemetry Device | Core unit for measuring and transmitting physiological data (e.g., ECG, blood pressure, temperature, activity) from conscious, freely-moving animals [2]. |

| Digital Telemetry Receiver | Captures the wireless signal transmitted by the implanted tag. Modern digital systems offer multiple channels, extended range, and reduced interference [2]. |

| Data Archiving Software | Securely stores continuous, high-resolution data streams for retrospective analysis, such as breakpoint analysis [1]. |

| Magnetometer-Magnet Pair | A sensor and magnet duo used to measure fine-scale, peripheral body movements (e.g., jaw angle, fin position, ventilation rates). This method enables direct measurement of specific behaviors that are difficult to infer from body-mounted tags alone [5]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | For performing advanced statistical analyses, including breakpoint analysis and linear mixed-effect modeling, to quantify recovery timelines and the influence of various factors [1]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

1. Problem: High rates of premature tag loss in a field study.

- Potential Cause: Excessive hydrodynamic drag or lift forces generated by the tag, leading to increased detachment stress or changes in animal behavior that promote tag shedding [7] [8].

- Solution:

- Redesign: Prior to field deployment, use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to simulate and optimize the tag's shape. Designs incorporating narrow elliptical profiles, pointed tails, and features like canards or tabs can reduce drag by over 50% and lift by over 80% [9].

- Repositioning: Use CFD analysis to identify the optimal attachment site. For many species, placing the tag on the posterior-dorsal region minimizes impact compared to fin mounting, which can increase drag by over 30% [10].

2. Problem: Tagged animals show reduced foraging effort or altered diving behavior.

- Potential Cause: Increased energetic cost of transport due to tag drag, leaving less energy for foraging activities [1] [7].

- Solution:

- Quantify Impact: Conduct controlled captive studies to measure behavioral changes, such as swim speed, dive duration, and foraging success, comparing tagged and untagged animals [7].

- Validate Design: Use these behavioral metrics to validate CFD predictions and refine tag designs. A study on grey seals confirmed that a redesigned tag (8.6% additional drag) caused significantly less behavioral impact than a previous model (16.4% additional drag) [7].

3. Problem: Data collected indicates unrepresentative animal behavior.

- Potential Cause: The tag itself is impeding natural movement, or the sensor placement is unable to capture key peripheral behaviors (e.g., jaw movement, fin beats) [5].

- Solution:

- Minimize Interference: Adopt the principles of refined tag design to minimize hydrodynamic loading [9] [11].

- Use Magnetometry: For measuring specific behaviors, employ a magnetometer on the main tag and a small magnet on the moving appendage (e.g., jaw, fin). This allows direct measurement of behaviors like foraging or ventilation without the need for bulky sensors on delicate structures [5].

4. Problem: Uncertainty in translating CFD simulation results to real-world animal performance.

- Potential Cause: CFD models may not fully capture the complex, dynamic interactions between the animal's body, the tag, and the fluid environment [10] [12].

- Solution:

- Experimental Validation: Complement CFD with physical validation methods such as Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) in flume tanks to characterize the flow field around the tag [11].

- In-situ Calibration: Use captive animal trials, where feasible, to correlate simulated drag forces with empirically measured changes in swimming energetics or behavior [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is drag considered a more critical factor than tag mass for many aquatic species? A1: Large marine animals are buoyant in water, so tag mass is often a minor concern. However, drag forces increase with the square of velocity. For fast-swimming animals, the hydrodynamic load from a poorly designed tag can become the dominant force, significantly increasing swimming costs and altering natural behavior, even for tags that are a very small percentage of the animal's body mass [7] [12].

Q2: What are the limitations of the traditional "3% body mass rule" for tag weighting? A2: The 3% rule (and similar guidelines) focuses solely on mass and does not account for hydrodynamic impacts like drag and lift [8] [12]. For aquatic and aerial species, a small but poorly streamlined tag can generate substantial hydrodynamic loading, making the rule insufficient. A more holistic approach that includes drag minimization through design and positioning is recommended [10] [12].

Q3: How can I measure specific animal behaviors without attaching large sensors to fragile appendages? A3: The magnetometry method provides a solution. By attaching a small, lightweight magnet to the appendage (e.g., jaw, flipper, fin) and using a magnetometer on the main tag, you can measure changes in the magnetic field strength to calculate the distance and angle of the appendage's movement. This technique has been successfully used to quantify shark jaw angles, scallop valve openings, and squid fin movements [5].

Q4: What is the benefit of generating "negative lift" or downforce in a tag design? A4: For tags attached to the dorsal side of an animal, the flow is non-axisymmetric; water moves faster over the tag than under it, creating a pressure differential that results in upward lift. This force can strain the attachment and promote detachment. Designs that incorporate features like inverted wings and underbody channels can counteract this by generating downforce, improving attachment stability and reducing the overall load on the animal [11].

Quantitative Data on Tag-Induced Hydrodynamic Loads

The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies on the hydrodynamic impact of biologging tags.

Table 1: Measured Increases in Hydrodynamic Drag from External Tags

| Species | Tag Attachment Method / Type | Drag Increase | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mako Shark (2.95 m) | Fin-mounted tag | 17.6% - 31.2% (across 0.5-9.1 m/s) | Fin mounting has a severe impact; optimal dorsal body placement is significantly better. | [10] |

| Mako Shark (1 m) | Dorsal-mounted archival tag | 5.1% - 7.6% | Highlights size-dependent impact; small sharks experience a considerable energetic cost (~7% of daily energy). | [10] |

| Grey Seal | SMRU GPS/GSM Tag (Gen 1) | 16.4% additional drag | Caused significant changes in foraging behavior in captive trials. | [7] |

| Grey Seal | Redesigned SMRU Tag (Gen 2) | 8.6% additional drag | Demonstrated significant behavioral improvement over Gen 1, validating the redesign. | [7] |

| Marine Mammals (General) | Novel Streamlined Tag (Model D) | Drag reduced by up to 56% vs. baseline | Design features (elliptical shape, pointed tail, dimples) dramatically improve performance. | [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Behavioral and Energetic Impacts of Tags on Captive Marine Mammals

This protocol is adapted from studies on phocid seals [7].

- Animal Preparation: Wild-caught animals are temporarily housed in a controlled pool facility. Under anesthesia, a baseplate is bonded to the fur on the dorsal neck region.

- Tag Attachment: Replica tags (matching the size, shape, and buoyancy of functional tags) are attached to the baseplate. A control treatment involves the baseplate only.

- Experimental Setup: Animals are trained to perform a simulated foraging task, swimming a set distance from a breathing chamber (integrated with respirometry) to an artificial prey patch.

- Data Collection:

- Energetics: The open-flow respirometry system measures oxygen consumption, allowing calculation of metabolic rate and energy expenditure.

- Behavior: Dive profiles, swim speeds, transit times to the feeder, and time spent foraging are recorded.

- Experimental Design: Animals are exposed to different tag treatments (e.g., no tag, old tag design, new tag design) in a randomized block design, with each treatment typically lasting several days.

- Data Analysis: Linear mixed-effects models are used to determine the effect of the tag on energetic and behavioral metrics, controlling for individual variation.

Protocol 2: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Workflow for Tag Impact Assessment

This protocol outlines the standard CFD process for evaluating tag hydrodynamics [10] [11].

- Geometry Acquisition: Create or obtain accurate 3D digital models (CAD) of the animal's body and the tag.

- Meshing: Generate a computational mesh around the geometry. This involves creating a virtual bounding box (the domain) and discretizing it into millions of small control volumes (cells). A mesh independence study is conducted to ensure results are not dependent on cell size.

- Boundary Conditions & Physics Setup:

- Define the fluid properties (e.g., seawater density and viscosity).

- Set the inlet velocity to the expected range of animal swim speeds.

- Apply a turbulence model, such as the k-omega SST model, which is well-suited for simulating flow over streamlined bodies.

- Simulation: Solve the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations iteratively until the solution converges.

- Post-processing & Analysis: Extract quantitative data on pressure and shear stress distributions on the tag and animal surface. Calculate the total hydrodynamic forces, including drag and lift.

Methodologies and Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Hydrodynamic Impact Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Numerically simulates fluid flow around a digital model of the animal and tag to predict drag, lift, and pressure distributions. | OpenFOAM, Ansys Fluent. Used to optimize tag shape and placement before manufacturing [10] [13]. |

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) | An experimental technique that uses lasers and cameras to measure velocity fields in a fluid. Used to validate CFD simulations. | Characterizing the wake and flow separation around a prototype tag in a flume tank [11]. |

| Open-Flow Respirometry System | Measures an animal's oxygen consumption in real-time, allowing for the calculation of metabolic rate and energetic cost. | Quantifying the increased energy expenditure of a seal swimming with a tag versus without one [7]. |

| Neodymium Magnets & Magnetometers | A paired system where the magnet is affixed to a moving appendage and the magnetometer (on the main tag) measures the changing magnetic field to infer movement. | Quantifying jaw angles in foraging sharks or valve gape angles in scallops [5]. |

| High-Resolution 3D Scanner | Creates accurate digital models of animal morphologies and tag prototypes for use in CFD simulations. | Generating the precise geometry of a mako shark's body for virtual tag testing [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the "Dinner Bell Effect" and how does it relate to my telemetry data?

- A: The "Dinner Bell Effect" is a documented phenomenon where grey seals learn to associate the sound from acoustic fish tags with a food source. In experiments, seals found tagged fish faster and revisited the tagged location more often, indicating that the anthropogenic noise was used as a foraging cue [14]. This can bias foraging data and predation studies.

Q: My study subject's diving depth and duration have changed post-tagging. Is this related to tag attachment?

- A: Yes, this is a documented behavioral change. Studies on young-of-year grey seals show that dive depth and duration typically increase in the first months of nutritional independence as the animals develop physiologically and refine their foraging strategies [15]. Your data may reflect this natural ontogeny, but the tag's drag and weight can also influence energetics and movement.

Q: Could the telemetry tag itself affect the seal's physiology or behavior beyond physical drag?

- A: Potentially, yes. Beyond the physical burden, some research suggests that nonionizing electromagnetic fields (EMF) from transmitting tags may affect wildlife, as many species are sensitive to electromagnetic fields for navigation and other life functions. The biological effects of these exposures are an area of ongoing research [6].

Q: How can I account for premature tag failure in my long-term study?

- A: Concurrent tag-life studies are recommended. Deploy a sample of tags alongside your study tags to model failure times. Research indicates that vitality models often provide the best fit for these failure-time datasets, as they can account for both early failures and anticipated battery life [16].

Troubleshooting Common Data Interpretation Issues

Problem: Misinterpreting lack of movement as a mortality event.

- Solution: Grey seals, particularly larger individuals, can remain stationary for extended periods. Relying solely on movement data from accelerometers or mortality switches can lead to false positives. Implement a state-space model that incorporates the probability of misclassifying live individuals as dead, especially for species with cryptic resting behaviors [17].

Problem: Observed predation rates on tagged fish are higher than expected.

- Solution: Your data may be influenced by the "Dinner Bell Effect." Acoustic tag signals can make tagged fish more vulnerable to predation by acoustically-oriented predators like grey seals. This is a source of bias that should be acknowledged, and corrections may be necessary for survival estimates [14].

Problem: Data shows anomalous behavioral patterns post-tagging.

- Solution: A period of altered behavior following tag deployment is common. A study on sea otters found a return to baseline body temperature and dive behavior occurred approximately 14-18 days after internal tag implantation, indicating a recovery period from the procedure [1]. Allow for an acclimation period in your analysis.

Documented Behavioral Changes & Experimental Data

Quantitative Data on Grey Seal Foraging Behavior with Acoustic Tags

The following data is derived from a controlled experiment where 10 grey seals were tested in a pool with 20 foraging boxes, one containing a tagged fish and one with an untagged fish [14].

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Findings

| Behavioral Metric | Result | Statistical Significance & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of Finding Tagged Fish | Tagged box found after significantly fewer non-tag box visits [14]. | Learned to use the acoustic signal as a beacon to locate prey efficiently. |

| Revisitation Behavior | Seals revisited the box containing the tag more often than any other box [14]. | Indicates the acoustic signal created a salient location marker. |

| Learning Curve | Time and number of boxes needed to find both fish decreased significantly across trials [14]. | Demonstrates rapid associative learning between the tag signal and food reward. |

| Signal vs. Chemosensory Cues | In control tests with no fish (only a tag), the tagged box was still found significantly faster [14]. | Confirms that seals were primarily cueing into the acoustic signal, not smell. |

Diving Behavior Development in Juvenile Grey Seals

Table 2: Post-weaning Dive Behavior Development

| Dive Metric | Trend | Behavioral Context |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Depth & Duration | Increased in the first two months post-weaning, stabilizing by April [15]. | Reflects physiological development and refinement of foraging skills. |

| Benthic vs. Pelagic Diving | More benthic diving occurred in spring, peaking during daylight hours [15]. | Spatiotemporally linked to prey availability (e.g., sand lances) and diel rhythms. |

| Dive Type by Habitat | Benthic dives were more frequent in sandy shoals, banks, and wind energy areas [15]. | Shows habitat-specific foraging tactics, which could be disrupted by seafloor infrastructure. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing the "Dinner Bell Effect" with Acoustic Tags

This protocol is adapted from the experiment that documented seals using acoustic tag signals to find food [14].

- Objective: To determine if grey seals learn to use sounds from acoustic fish tags as an indicator of food location.

- Subjects: 10 juvenile grey seals with no prior association between sound and food.

- Testing Environment: A 37.5 m x 6 m pool with 20 foraging boxes placed on the bottom.

- Tag Specifications: Vemco V9–2H coded fish tags emitting an intermittent 69 kHz signal (source level 151 dB SPL re 1 µPa).

- Procedure:

- Desensitization: Allow seals to freely retrieve fish from a single box in a separate pool.

- Learning Trials: For each trial, place one tagged fish and one untagged fish in two pseudo-randomly selected boxes. The other 18 boxes remain empty.

- Data Logging: Use magnetic reed switches on box doors and fish plates to log all visit and retrieval events via a customized program.

- Trial Endpoint: Remove the seal 5 minutes after both fish are found or after 1 hour.

- Controls:

- Tag-Only Control: Place acoustic tags in one box with no fish in any box to eliminate chemosensory cues.

- All-Fish Control: Place inaccessible fish pieces in all 18 other boxes to make chemosensory cues less reliable.

- Key Measurements: Number of box visits to find the tagged fish, revisitation rates, and time to locate fish across 20 trials.

Protocol 2: Establishing a Baseline for Diving Behavior

This protocol outlines the method for collecting baseline diving data, critical for assessing tag impacts [15].

- Objective: To investigate the post-weaning horizontal movements and dive behaviors of a recovering population prior to major ocean industrialization.

- Subjects: 63 young-of-year grey seals.

- Tag Specifications: Argos satellite relay data loggers (SRDLs) in various configurations (SPOT-293, SPLASH10) manufactured by Wildlife Computers.

- Deployment: Tags were affixed to seals at pupping colonies and haul-out sites. Tags performed onboard processing and relayed summarized data via the Argos satellite system.

- Data Analysis:

- Movement: Analyze location data to create utilization distributions and assess overlap with anthropogenic zones (e.g., wind energy areas).

- Dive Classification: Classify dives as benthic (near the seafloor) or pelagic (in the water column) based on dive depth relative to bathymetry.

- Temporal Analysis: Examine dive metrics (depth, duration) over time and in relation to diel cycles.

Visualizations

Experimental Workflow for "Dinner Bell" Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Telemetry Impact Studies

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Coded Acoustic Tags | Emit unique ultrasonic signals to mark individuals or prey; the core stimulus in behavioral effect studies. | Vemco V9–2H tags (69 kHz) used to test the "dinner bell effect" [14]. |

| Satellite Relay Data Loggers (SRDLs) | Animal-borne tags that collect and transmit data on location, depth, and temperature via satellite. | Wildlife Computers SPOT & SPLASH tags used to track grey seal movement and diving [15]. |

| Vitality Model Software | Statistical models used to analyze tag-failure times, accounting for both early failure and battery lifespan. | Recommended for correcting survival estimates in the presence of tag failure [16]. |

| Magnetometer-Magnet Coupling | A method to measure fine-scale movements (e.g., jaw angle, fin position) not easily captured by standard tags. | Emerging technology for direct measurement of foraging and ventilation behaviors [5]. |

| Bayesian State-Space Models | Statistical frameworks to account for state misclassification (e.g., alive vs. dead) in telemetry data. | Used to model mortality events and reduce false positives from lack of movement [17]. |

For decades, the "3-5% rule"—the guideline that a device should not exceed 3-5% of an animal's body weight—has been a cornerstone of ethical practice in animal-borne telemetry. However, emerging research reveals that this weight-centric approach is dangerously insufficient. It fails to account for critical factors like hydrodynamic drag, species-specific morphology, and tag placement, which can significantly impact animal welfare and data integrity. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols to help researchers identify and mitigate the non-weight impacts of biologging devices, advancing the field toward more refined and ethical tagging practices.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My tagged animals are showing reduced swimming speeds or altered diving behavior. What could be causing this beyond tag weight?

A: The issue is likely increased hydrodynamic drag from your tag. A recent computational fluid dynamics (CFD) study on mako sharks quantified that a fin-mounted tag can increase drag by 17.6% to 31.2% across a range of swimming speeds, forcing the animal to expend more energy for the same movement [10]. This is a function of tag shape and placement, not just mass.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Isolate the Variable: Review your tag's shape and attachment site. Streamlined tags on the main body cause less drag than bulky tags on appendages.

- Compare to Baseline: If possible, compare the behavior of animals with dorsally-mounted tags to those with fin-mounted tags.

- Consult CFD Data: Refer to the table below for quantitative data on drag increases.

Q2: Post-tagging, my data shows elevated physiological metrics. Is this a tag effect or natural variation?

A: This is a common observation and is often a direct short-term effect of the tagging procedure itself. A study on sea otters with intra-abdominal tags found a significant, temporary increase in body temperature (Δ = 0.46°C) post-implantation, indicating an immune and inflammatory response to surgery [1]. Behaviorally, animals showed reduced foraging effort.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Establish a Baseline: In your analysis, identify and exclude this post-surgical recovery period. For sea otters, the return to baseline occurred at 14.61 ± 5.19 days for body temperature and 17.96 ± 1.9 days for behavior [1].

- Monitor Behavior: Look for reduced activity, diving, or foraging immediately after tagging as corroborating evidence of a recovery phase.

- Adjust Protocols: Consider this recovery window when planning the start of your official data collection period.

Q3: How can I pre-emptively determine the best tag shape and placement to minimize impact on my study species?

A: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling is the most effective method for predicting hydrodynamic impact before a field deployment. This technique simulates water flow around a 3D model of the animal with different tag configurations [10].

- Experimental Protocol: CFD Simulation

- Geometry Acquisition: Obtain or create a accurate 3D digital model of your study species.

- Model Tag Configurations: Add virtual tags of different shapes (e.g., spheroids vs. cylinders) to different attachment sites (e.g., dorsal fin, dorsal musculature).

- Set Simulation Parameters: Define the fluid (seawater), flow velocities (across the animal's natural speed range), and turbulence model (e.g., k-ω SST).

- Mesh and Solve: Discretize the domain into millions of cells and run the simulation using software like OpenFOAM.

- Analyze Results: Calculate and compare the drag forces, pressure distributions, and flow fields for each configuration to identify the optimal design [10].

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

Q4: The 2-5% weight rule is simple. Why should I adopt these more complex assessments?

A: While simple, the weight rule is fundamentally flawed because it ignores hydrodynamics. A small but poorly placed tag can create more drag and require more energy to carry than a larger, well-streamlined tag. Furthermore, mass alone does not predict physiological or behavioral impacts, such as the inflammatory response documented in sea otters [1]. Adopting a holistic impact assessment is critical for:

- Animal Welfare: Minimizing unnecessary energy expenditure and physical impact.

- Data Quality: Ensuring collected data reflects natural behavior, not tag-induced artifacts.

- Scientific Rigor: Applying modern, quantitative engineering principles to biological fieldwork.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research to guide experimental design and impact assessment.

Table 1: Hydrodynamic Impact of Tagging on Mako Sharks (CFD Study) [10]

| Shark Fork Length | Tag Placement | Tag Shape | Drag Increase | Equivalent Daily Energetic Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.95 m | Fin-mounted | Cylinder | 17.6% - 31.2% | Not Quantified |

| 1.0 m | Dorsal body | Archival | 5.1% - 7.6% | ~7% of daily requirement |

| >1.5 m | Dorsal body | Archival | Minimal | Minimal |

Table 2: Physiological & Behavioral Recovery Post-Tagging (Sea Otter Study) [1]

| Metric | Change Post-Implantation | Time to Return to Baseline (Days) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature | Increased by 0.46°C | 14.61 ± 5.19 | Immune response to surgery |

| Dive Behavior | Reduced foraging effort, shorter bouts | 17.96 ± 1.9 | Consistent across reproductive statuses |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Telemetry Tag Impact Assessment

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software (e.g., OpenFOAM) | Open-source software for simulating fluid flow and calculating hydrodynamic forces like drag on tagged animals [10]. |

| 3D Scanner / Morphometric Data | To create accurate digital geometries of study species for CFD simulations [10]. |

| Animal-borne Data Loggers (Tags) | Devices to record location, depth, acceleration, and physiological data; available in various shapes (e.g., spheroids, cylinders) and attachment types (e.g., fin, dorsal) [10]. |

| Internal Temperature & Activity Loggers | Implantable or ingestible sensors to monitor core body temperature and classify behavior post-tagging to establish recovery timelines [1]. |

| Resistance Training Equipment | For studies on muscle health, to investigate the role of resistance exercise in mitigating muscle loss during weight loss in obesity, a parallel concern in maintaining animal condition [18]. |

| High-Protein Dietary Formulations | Used in clinical studies to stimulate muscle protein synthesis and prevent breakdown; a concept transferable to nutritional support for captive or recovering tagged animals [18]. |

Force Balance Analysis in Tagged Marine Animals

The following diagram illustrates the complex forces acting on a tagged marine animal, which are central to understanding the limitations of the simple weight-based rule.

Ethical Imperatives and the 3Rs Framework in Wildlife Tagging

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Core Principles and Ethical Justification

Q1: How does the 3Rs framework specifically apply to wildlife tagging studies? The 3Rs framework—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—provides a vital ethical structure for animal biologging research. Its application ensures that tagging studies are conducted as humanely as possible while maintaining scientific integrity [19] [20].

- Replacement is applied by using technologies like computer simulations (e.g., Computational Fluid Dynamics) to model tag impacts before physical deployment on live animals [10].

- Reduction is achieved through appropriate experimental design and statistical analysis, ensuring the minimum number of animals are used to obtain statistically significant data [19] [20].

- Refinement involves modifying procedures to minimize pain and distress. This includes using smaller, less invasive tags, optimizing tag placement and attachment to reduce hydrodynamic drag, and employing novel methods like magnetometry to measure behavior with minimal animal disturbance [5] [10].

Q2: My tagging data shows anomalous swimming patterns. Could the tag itself be affecting the animal's behavior? Yes, this is a common concern. External tags can significantly impact an animal's hydrodynamics. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) studies on mako sharks show that tag placement and size directly affect drag and energy expenditure [10]. To troubleshoot:

- Review Tag Size: Ensure the tag's weight and size adhere to established guidelines, such as the 3% of body mass rule for birds or the 2% rule for teleost fish, while acknowledging these are not universally applicable [5] [10].

- Analyze Placement: CFD models indicate that tags mounted on fins can increase drag by 17.6% to 31.2%, drastically affecting swimming efficiency. Tags on the dorsal body cause less drag for larger sharks (>1.5 m) but are still impactful for smaller individuals [10].

- Refine Your Approach: Consider using smaller tags or alternative methods like magnetometry, which employs a small magnet and sensor to measure behaviors like jaw movement or fin beats without large, bulky devices [5].

Technical Implementation and Methodology

Q3: What is the magnetometry method for measuring behavior, and how is it implemented? Magnetometry uses a biologging tag's magnetometer as a proximity sensor for a small magnet affixed to a moving appendage. Changes in magnetic field strength correlate with the distance between the magnet and sensor, allowing direct measurement of peripheral body movements like gill covers, jaws, or fins [5].

Implementation Guide:

- Selection: Choose the smallest possible magnet and sensor combination. The magnet must have a "magnetic influence distance" greater than the maximum expected movement range [5].

- Placement: Affix the magnet to the moving appendage (e.g., the lower jaw) and the sensor tag to a stable body part. Magnets are often smaller and can be placed on more fragile structures [5].

- Orientation: For cylindrical magnets, orient the flat pole surfaces normal (perpendicular) to the magnetometer to maximize the signal range [5].

- Calibration: Essential for converting magnetic field strength into distance and joint angle. Calibrate by positioning the appendage at known distances and fitting the data to the model below [5].

Q4: How do I calculate hydrodynamic drag from a tag to ensure ethical compliance? Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is the primary tool for this. The process involves [10]:

- Geometry Definition: Creating a 3D model of the animal and tag.

- Meshing: Discretizing the computational domain into millions of small cells.

- Setting Parameters: Defining boundary conditions, fluid density (e.g., seawater), and flow velocity.

- Modeling: Solving the Navier-Stokes equations using turbulence models (e.g., k-ω SST).

- Analysis: Post-processing to calculate drag forces and compare tagged vs. untagged scenarios.

Table 1: Hydrodynamic Impact of External Tags on Mako Sharks (CFD Simulation Results)

| Shark Fork Length | Tag Placement | Swimming Speed Range | Drag Increase | Additional Daily Energetic Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.95 m | Dorsal Fin | 0.5 - 9.1 m/s | 17.6% - 31.2% | Not Specified |

| 1.5 m (Large) | Dorsal Body | 0.5 - 9.1 m/s | Minimal | Minimal |

| 1.0 m (Small) | Dorsal Body | 0.5 - 9.1 m/s | 5.1% - 7.6% | ~7% |

Table 2: WCAG 2.1 Color Contrast Requirements for Data Visualization

| Visual Element | Minimum Ratio (AA Rating) | Enhanced Ratio (AAA Rating) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Text | 4.5 : 1 | 7 : 1 |

| Large Text (≥18pt or ≥14pt bold) | 3 : 1 | 4.5 : 1 |

| User Interface Components & Graphical Objects | 3 : 1 | Not Defined |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Magnetometry for Behavioral Measurement

This protocol enables the measurement of specific, kinematically-driven behaviors (e.g., ventilation, foraging) that are difficult to isolate from whole-body movements using traditional tagging methods [5].

1. Sensor and Magnet Selection:

- Tags: Use high-frequency accelerometer and magnetometer tags (e.g., TechnoSmart Axy 5 XS, 100 Hz accelerometer) [5].

- Magnet Size: Select the smallest neodymium magnet possible. Determine the minimum size via benchtop tests where the magnet is manipulated at known distances from the magnetometer to ensure the magnetic field is detectable across the full range of motion [5].

- Mass Consideration: The combined mass of the tag and magnet should ideally be less than 3% of the animal's body mass, though athleticism and lifestyle should also be considered [5] [10].

2. On-Animal Placement:

- Based on the target behavior, affix either the magnet or the sensor to the moving appendage. For example:

- Scallop Valve Angle: Glue the sensor to the upper valve and the magnet to the lower valve [5].

- Shark Jaw Movement: Affix the magnet to the lower jaw and the sensor to the head or dorsal area.

- Fish Operculum Beat: Place the magnet on the operculum and the sensor nearby on the body.

3. Calibration Procedure: Calibration is critical for converting sensor output into meaningful kinematic data.

- The relationship between magnetic field strength (MFS) and distance is modeled by: (d = {\left[\frac{x1}{M(o)-x3}\right]}^{0.5} - x2) where (d) is the magnetometer-magnet distance, (M(o)) is the root-mean-square of tri-axial MFS, and (x1, x2, x3) are best-fit coefficients [5].

- To convert distance (d) to joint angle (a), use: (a = 2 \times \arcsin\left(\frac{0.5d}{L}\right) \times 100) where (L) is the distance from the body joint to the tag or magnet on the appendage [5].

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ethical Wildlife Tagging and Behavioral Inference

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Frequency Biologging Tag (e.g., with accelerometer & magnetometer) | Measures animal movement & orientation; core sensor for magnetometry. | Select based on sample rate (≥100 Hz for fine-scale behavior), memory, battery life, and size [5]. |

| Neodymium Magnet | Creates a measurable magnetic field for tracking appendage movement in magnetometry. | Choose the smallest size with sufficient "magnetic influence distance." Cylindrical magnets with large pole surfaces are recommended [5]. |

| Cyanoacrylate Glue (e.g., Reef Glue) | Securely attaches tags and magnets to animals in aquatic environments. | Must be non-toxic and provide a strong, durable bond for the study duration [5]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software (e.g., OpenFOAM) | Simulates fluid flow around tagged animals to quantify hydrodynamic impact (drag) before physical deployment [10]. | Requires a 3D model of the animal and tag. Uses RANS turbulence models (e.g., k-ω SST) for accurate results [10]. |

| Color Contrast Checker Tool (e.g., WebAIM) | Ensures data visualizations and interface components are accessible to all users, meeting WCAG guidelines [21] [22]. | Verify a minimum 4.5:1 ratio for text and 3:1 for UI components and large text [21] [22] [23]. |

From Theory to Practice: Cutting-Edge Methods for Tag Impact Reduction

Leveraging Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Streamlined Tag Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is CFD essential for designing animal-borne telemetry tags? CFD is a numerical technique that solves the governing equations of fluid flow, allowing researchers to simulate and analyze the hydrodynamic forces acting on a tag and the animal it is attached to with high accuracy and resolution [10]. It is essential because it enables the quantification of tag impact—such as increased drag and altered swimming characteristics—before physical prototypes are built or animals are tagged [10] [24]. This virtual testing helps in refining tag shape and placement to minimize adverse effects on animal welfare and data reliability [10].

Q2: What are the common CFD simulation errors that can affect my tag impact analysis? Several common errors can compromise your analysis:

- Poor Mesh Quality: A mesh with highly skewed cells or insufficient resolution can decrease numerical stability and produce inaccurate results [25] [26]. It is crucial to ensure high mesh quality, especially near the tag and animal body where flow gradients are high [25].

- Incorrect Convergence: Stopping a simulation before it has properly converged leads to unreliable data. For steady-state simulations, ensure residuals fall below an appropriate level, typically 10⁻⁴, and that monitor points (e.g., drag force) stabilize [25] [26].

- Inappropriate Physics Models: Selecting incorrect physical models (e.g., turbulence, multiphase) for the flow conditions can yield misleading results. It is best practice to start with simpler models, like laminar flow, and gradually increase complexity [25] [26].

- Ill-Posed Boundary Conditions: Recirculation at solution boundaries, particularly the outlet, is a common cause of failure. This occurs when flow re-enters the domain with undefined properties. Extending the computational domain or modifying the geometry can resolve this [27].

Q3: How can I visualize flow fields to better understand tag-induced drag? Streamline plots are a powerful tool for this purpose. They represent the paths followed by fluid particles, allowing you to identify complex flow patterns like vortices and separation zones caused by the tag [28]. The density of streamlines can indicate flow velocity, with closely spaced lines showing high-velocity regions [28]. For a more dynamic and realistic representation, tools like Altair Inspire allow you to animate streamlines, visualizing the flow as a continuous stream of particles [29].

Q4: Are rainbow color maps suitable for visualizing CFD results for tag design? While common, simple rainbow color maps are often not the best choice [30] [31]. They can obscure data and be difficult for some users to interpret. Instead, consider:

- Perceptually Uniform Maps: These have a smooth variation in lightness, making it easier to understand data sequences (e.g., Turbo, which is also available in Ansys Fluent) [30] [31].

- Diverging Maps: Ideal for highlighting variations about a central value, such as pressure coefficients or vorticity [30] [31].

- Field-Specific Maps: Some CFD software, like Ansys Fluent, provides recommended colormaps for specific field variables like temperature or velocity [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: CFD for Tag Design

This guide addresses specific issues you might encounter when simulating the hydrodynamics of animal-borne tags.

Problem 1: Simulation will not converge or residuals are oscillating.

- Checklist:

- Verify Mesh Quality: Check the mesh for highly skewed or non-orthogonal cells. Use mesh improvement tools and refine the mesh near the tag and animal's body where high gradients are expected [25] [26]. For wall-bounded flows, ensure the mesh resolution is fine enough to resolve the shear layer [25].

- Review Boundary Conditions: Double-check units and direction vectors on inlets and outlets. Ensure that backpressure at the outlet is not excessively high, as this can cause the mass flow to drop and the solution to fail [26] [27].

- Adjust Solver Settings: Reduce the under-relaxation factors for variables by about 10% to improve stability in highly nonlinear problems [26]. For pseudo-transient simulations, reduce the time step to resolve small flow features [26].

- Check for Physical Transients: If residuals and force monitors oscillate around a mean, the flow may be inherently transient. Switch from a steady-state to a transient solver [26].

Problem 2: Simulation converges, but the drag forces seem unrealistic.

- Checklist:

- Isolate the Problem Component: Create monitor points for drag on the animal's body and the tag separately. This helps identify if the issue is localized to the tag or more widespread [26].

- Inspect Flow Field: Use post-processing to create cut planes and isosurfaces. Look for abnormalities in flow speed, direction, or unexpected separation zones caused by the tag [26].

- Validate with a Simpler Case: Reduce the complexity of the model. For example, simulate the tag on a simple, representative shape (like a cylinder) to verify the baseline drag is sensible before moving to the complex animal geometry [25] [26].

- Confirm Model Appropriateness: Ensure the selected turbulence model (e.g., k-ω SST) is suitable for the flow regime and separation patterns you are analyzing [25] [10].

Problem 3: Flow visualization does not clearly show the tag's hydrodynamic impact.

- Checklist:

- Optimize Streamline Seeding: Instead of releasing particles simultaneously over an area, use a continuous random distribution to create a more natural and informative visualization [32].

- Use Contrasting Colormaps: Apply a diverging colormap to variables like pressure or vorticity to clearly distinguish between positive and negative effects induced by the tag [30] [31]. Avoid colormaps with very dark colors that can obscure the 3D shape of the animal [31].

- Compare Tagged vs. Untrapped: Always run a simulation of the untagged animal under identical conditions. Visualizing the differences in flow separation and wake structure is the most direct way to illustrate the tag's impact [10].

Quantitative Data on Tag Impact

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from CFD studies on the hydrodynamic impact of tags, informing ethical design thresholds.

Table 1: Quantified Hydrodynamic Impact of Animal-Borne Tags from CFD Studies

| Animal Model | Tag Attachment Site | Key Quantitative Finding | Implied Energetic Cost | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mako Shark (2.95 m fork length) | Fin | Drag increased by 17.6% to 31.2% across a range of swim speeds. | Not quantified, but significant increase in energetic cost of transport is implied. | [10] |

| Mako Shark (1 m fork length) | Dorsal Musculature | Drag increased by 5.1% to 7.6%. | Energetic cost equivalent to ~7% of daily energetic requirement. | [10] |

| Grey Seal | Body (Gen 1 Tag) | Tag design associated with 16.4% additional drag. | Significant change in diving and foraging behavior observed. | [24] |

| Grey Seal | Body (Gen 2 Tag) | Redesigned tag associated with 8.6% additional drag. | Behavioral impact was reduced compared to the Gen 1 tag. | [24] |

Experimental Protocol: CFD Workflow for Tag Impact Assessment

This protocol details the methodology for using CFD to quantify the hydrodynamic impact of an animal-borne tag, as applied in recent research [10].

1. Geometry Preparation and Domain Definition

- Create a watertight, simplified 3D geometry of the animal and the tag. The level of detail should balance biological accuracy with computational cost.

- Define a virtual bounding box (computational domain) around the geometry. The domain should be large enough to avoid boundary effects on the flow around the animal.

2. Mesh Generation (Discretization)

- Discretize the domain into millions of small polyhedral control volumes (a mesh). The mesh must be fine enough to resolve the flow features.

- Critical Step: Implement mesh refinement near the animal's body and the tag surface to accurately capture the boundary layer and high-gradient regions. The resolution of the wall-bounded shear layer is crucial, often requiring a y+ value of less than 1 [25].

3. Boundary Conditions and Solver Settings

- Set the inlet boundary condition to the desired flow velocity, covering the animal's realistic swim speed range.

- Set the outlet boundary condition to a specified pressure.

- Select an appropriate turbulence model. The k-ω SST model is commonly used for such external flows as it performs well in predicting flow separation [10].

- Use a steady-state, pressure-based solver (e.g.,

simpleFoamin OpenFOAM) for initial analysis [10].

4. Modeling and Convergence

- Run the simulation iteratively until the computed flow variables converge towards a stable solution.

- Monitor the residuals of key variables (continuity, momentum) and ensure they drop below 10⁻⁴ [25]. Also, set up force monitors to track drag and lift forces on the tag and animal until they stabilize.

5. Post-Processing and Analysis

- Calculate the hydrodynamic forces (drag and lift) acting on both the tagged and untagged animal models.

- Visualize the flow using streamlines, pressure contours, and vorticity isosurfaces to identify flow separation, vortices, and wake structures caused by the tag [28] [30].

- Quantify the percentage increase in drag due to the tag and correlate this with potential increases in the animal's energetic cost of transport [10].

Research Reagent Solutions (Essential CFD Tools)

This table lists the essential software and modeling components required to conduct CFD analyses for tag design.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Models for CFD Analysis of Animal-Borne Tags

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Tag Impact Research |

|---|---|---|

| CFD Solver Software | OpenFOAM [10], ANSYS Fluent [30], FINE/Turbo (NUMECA) [27] | The core numerical engine that solves the governing Navier-Stokes equations to simulate fluid flow around the animal and tag. |

| Turbulence Models | k-omega SST [10], k-epsilon | Mathematical models used to approximate the effects of turbulence in the flow, critical for predicting drag and flow separation accurately. |

| Visualization & Post-Processing | ParaView [31], Altair Inspire [29], ANSYS CFD-Post [32] | Software used to visualize simulation results, including streamlines, pressure contours, and vorticity, and to calculate integrated forces like drag. |

| Colormaps for Visualization | Turbo [30], Field-specific maps (e.g., field-temperature) [30], Diverging maps (e.g., split-bgr-modern-white) [30] | Perceptually uniform color schemes applied to data plots to improve clarity and accurately represent physical quantities like velocity and pressure. |

The use of animal-borne telemetry tags is fundamental for studying the behavior, ecology, and physiology of marine animals. However, researchers have long recognized that the devices essential for data collection can themselves alter the very subjects they are designed to study. A primary concern is the hydrodynamic impact of tags, which increases the energetic costs of swimming for marine creatures through added drag. This not only raises animal welfare concerns but also compromises the validity of collected data, as tagged animals may modify their natural behavior to compensate for the increased load.

This case study details the successful refinement of the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) Instrumentation Group's GPS/GSM tag, a process that achieved a nearly 50% reduction in hydrodynamic drag. The work exemplifies a growing commitment within the biologging community to refine tagging practices by applying rigorous engineering principles. The methodology and findings presented here provide a framework for researchers seeking to minimize their experimental impact and enhance data quality in animal telemetry studies [33].

The Problem: Quantifying Tag-Induced Drag

Documented Impacts on Animal Behavior and Energetics

Initial investigations revealed the very real consequences of tag drag. Studies on grey seals carrying the first-generation tag (Gen 1) demonstrated a significant change in their behavior, confirming that the hydrodynamic load was substantial enough to alter natural activity patterns. This behavioral shift indicated both a welfare concern for the animals and a potential source of bias in the scientific data being gathered [33].

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become a critical tool for quantifying the hydrodynamic forces acting on tagged animals. CFD is a numerical technique that solves the physical laws governing fluid flow, allowing researchers to simulate water movement around a virtual model of an animal and its tag. This process provides detailed information on pressure distribution and shear stress, which can be used to calculate the drag force impeding the animal's movement [10].

The drag force experienced by a tagged animal is not a simple function of tag weight. It is primarily influenced by:

- Tag Shape and Size: Bulky, boxy shapes create more flow disruption and pressure drag than streamlined designs.

- Attachment Position: Tags placed on protuberances like dorsal fins can cause significant drag, with studies on mako sharks showing increases of 17.6% to 31.2% for fin-mounted tags [10].

- Proximity to the Body: A tag that stands away from the animal's body creates a larger disruptive footprint in the flow.

Table 1: Quantified Drag Increases from Various Tag Configurations (Based on CFD Studies)

| Species | Tag Attachment Position | Increase in Drag | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mako Shark (2.95 m) | Dorsal Fin | 17.6% - 31.2% | [10] |

| Mako Shark (1 m) | Dorsal Musculature | 5.1% - 7.6% | [10] |

| Grey Seal | Gen 1 SMRU Tag | 16.4% | [33] |

The Solution: A Two-Phase Redesign Methodology

The development of the low-drag SMRU tag followed a structured, iterative approach combining computational modeling and empirical validation.

Phase 1: Computational Design & Fluid Dynamics Analysis

The first phase involved using CFD to model and compare the hydrodynamic performance of different tag housing designs.

Experimental Protocol: CFD Simulation

- Geometry Acquisition: Create or obtain an accurate 3D digital model (geometry) of the marine animal and the tag.

- Meshing: Discretize the computational domain surrounding the geometry into millions of small polyhedral cells, forming a mesh.

- Boundary Condition Setting: Define key physical parameters, including water flow velocity, fluid density, and how the surfaces interact with the flow.

- Modeling: Use a solver (e.g., OpenFOAM's

simpleFoamfor steady-state flow) to iteratively compute flow variables (velocity, pressure) for each cell in the mesh until the solution converges. - Post-processing: Analyze the results to calculate key metrics like drag force and visualize flow patterns and pressure distributions [10].

The CFD analysis allowed engineers to identify areas of high pressure drag and flow separation. The Gen 1 tag likely featured geometric disruptions that created a large wake behind it. The redesigned Gen 2 tag focused on a more streamlined shape that minimized its frontal cross-sectional area and allowed water to flow around it more smoothly, significantly reducing the drag coefficient [34].

Phase 2: Empirical Validation with Captive Animals

CFD predictions must be validated with real-world testing. The redesigned Gen 2 tag was deployed on captive phocid seals to compare its performance against the Gen 1 tag.

Experimental Protocol: Captive Diving Trials

- Subject & Tag Deployment: Fit captive grey seals with either the Gen 1 or the redesigned Gen 2 tag.

- Behavioral Monitoring: Record the seals' swimming and diving behavior using video and sensor data.

- Data Analysis: Compare key behavioral metrics (e.g., swim speeds, dive profiles, activity budgets) between seals carrying the two tag generations.

- Drag Force Correlation: Assess whether observed changes in swim speed are consistent with predictions from CFD drag estimates [33].

The results were conclusive: seals carrying the Gen 2 tag exhibited significantly different behavior compared to those with the Gen 1 tag, and these changes were consistent with a reduced hydrodynamic burden. This confirmed that the redesign was successful in mitigating the tag's impact [33].

Table 2: Key Outcomes of the SMRU Tag Redesign

| Metric | Gen 1 Tag | Gen 2 Tag | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional Drag | 16.4% | 8.6% | 47.6% reduction |

| Observed Seal Behavior | Significant change from baseline | Significantly less impact than Gen 1 | Successful mitigation |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Variance in Animal Swim Speeds After Tagging

- Potential Cause 1: High drag load from the tag is causing the animal to fatigue quickly or alter its gait.

- Solution: Verify the tag's size-to-animal ratio is within ethical guidelines. Redesign the tag housing for better hydrodynamics using CFD analysis [10] [34].

- Potential Cause 2: The tag is improperly positioned, creating asymmetric drag or disrupting locomotion.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the attachment site using CFD to find a location that minimizes flow disruption, such as flush against the dorsal musculature rather than on a fin [10].

Problem: Premature Tag Detachment

- Potential Cause 1: Hydrodynamic forces (drag and lift) on the tag exceed the attachment mechanism's strength.

- Solution: Redesign the tag to lower its drag and lift profile. For suction cups, ensure the housing is designed to keep the cup close to the attachment surface to minimize peeling forces [34].

Problem: Inaccurate Behavioral Data from Tag Sensors

- Potential Cause: The animal's behavior is atypical due to the energetic cost or physical irritation of the tag.

- Solution: Conduct controlled captive studies to compare the behavior of tagged vs. untagged animals, and use CFD to quantify and minimize the tag's hydrodynamic impact [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "3% rule" for tag weight, and is it sufficient?

- The 3% rule is a common guideline in avian biologging suggesting a tag should weigh no more than 3% of the animal's body mass. However, this rule is criticized for not accounting for hydrodynamic effects like drag, which can be a more significant cost than weight for swimming animals. A tag that is hydrodynamically "heavy" can be detrimental even if it is lightweight. A comprehensive assessment using CFD is recommended [10].

Q2: How can I measure or estimate the drag of my tag without a water flume?

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is the most practical method. It allows you to simulate water flow around a 3D model of your tag and animal at various speeds to calculate drag forces accurately. While it requires expertise, open-source software like OpenFOAM is available [10] [34].

Q3: My tag is already built. What is the single most impactful change I can make to reduce its drag?

- Repositioning the tag is often the most effective quick win. Moving a tag from a protruding structure like a dorsal fin to a location flush with the body's contour (e.g., the dorsal musculature) can dramatically reduce drag, as shown in shark studies [10].

Q4: Are there bio-inspired designs for drag reduction?

- Yes, bio-inspired designs are a promising field. For example, research into the scales of Paramisgurnus dabryanus (loach) has shown that its surface microstructure can create a pressure gradient and low-speed vortex effect, reducing friction drag by over 9%. Such biomimetic principles could be applied to future tag surfaces [35].

Essential Workflow & Research Reagents

Tag Optimization Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, evidence-based process for refining animal-borne tags to minimize impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Tag Impact Research

| Tool / Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | To simulate and quantify hydrodynamic forces on virtual models of tagged animals. | Predicting drag increases for different tag shapes on a shark model before manufacturing [10] [34]. |

| 3D Animal & Tag Geometries | Serves as the digital model for CFD simulations. | Creating an accurate surface mesh of a seal to simulate flow patterns [10]. |

| Open-Source Solvers (e.g., OpenFOAM) | Provides the numerical engine for performing CFD calculations. | Running RANS (k-ω-SST) turbulence models to resolve flow around a tag [10]. |

| Water Flumes / Tunnels | To physically validate CFD predictions using scale models or actual tags. | Measuring the drag force on a 3D-printed tag prototype at various flow speeds [34]. |

| Captive Animal Colonies | To conduct controlled experiments on behavioral and energetic impacts. | Comparing the swim speed and dive duration of seals fitted with different tag generations [33]. |

| High-Resolution Biologgers (Accelerometers, GPS) | To collect behavioral data for impact assessment during trials. | Quantifying stroke frequency or energy expenditure in tagged vs. untagged animals [33] [36]. |

The successful redesign of the SMRU seal tag, achieving a near 50% reduction in drag, stands as a benchmark in the field of ethical and sustainable biologging. This case study demonstrates that a methodology combining predictive computational modeling with rigorous empirical validation is not just ideal, but essential for minimizing the impact of research tools on marine animals.

The future of tag impact reduction lies in continued interdisciplinary collaboration. Integrating bio-inspired designs from fish scales [35], developing smaller and more efficient electronics, and establishing species-specific size thresholds for tagging are all critical steps forward. By adopting these refined practices, researchers can ensure that the data they collect truly reflects the natural lives of the animals they study, while upholding the highest standards of animal welfare.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Tagging Challenges

1. My tag is transmitting far fewer locations than expected. What could be wrong?

The vertical placement of the tag on the animal's body significantly influences transmission success. Tags positioned higher on the dorsal fin experience longer and more frequent antenna exposure. A study on a killer whale demonstrated that a tag placed 33 cm higher on the dorsal fin generated more than twice as many location estimates (540 vs. 245) and locations of higher quality (50% vs. 90% in the lowest-quality Argos class) [37]. Ensure your tag is positioned at the highest feasible point on the dorsal fin to maximize air exposure during surface breaks.

2. Could my tag placement be affecting the animal's swimming and health?

Yes. Tag placement and design can have significant hydrodynamic consequences. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations on mako sharks show that fin-mounted tags can increase drag by 17.6% to 31.2%, forcing the animal to expend more energy [10]. Furthermore, penetrative tagging methods (e.g., bolting tags through the dorsal fin) can cause wounds, biofouling, fin deformation, and in the case of animals taken out of the water for tagging, potentially severe internal hemorrhaging [38]. Whenever possible, opt for non-penetrative attachment methods like fin clamps or braces, and consider the animal's size relative to the tag.

3. My analysis suggests unusual animal movement patterns. Could the data be biased by tag performance?

Absolutely. Differences in tag performance directly affect derived movement metrics. Research comparing two tags on the same killer whale found that the path from the higher-performing tag was 1.5 times longer and yielded a higher average speed and more extreme turning angles than the path from the lower tag [37]. Behavioral analysis (e.g., classifying "searching" vs. "transit" states) can also be affected, with one study finding that 30% of paired locations were assigned to different behavioral states depending on which tag's data was used [37]. Always consider tag placement as a covariate in your movement analysis.

4. How can I account for premature tag failure in my survival studies?

It is critical to conduct concurrent tag-life studies where a sample of tags is activated alongside those used in your survival study. Model the failure times to correct your survival estimates. A meta-analysis of 42 acoustic tag-life studies found that vitality models best fit the failure-time data in 57% of cases, as they can characterize both early failure due to manufacturing defects and anticipated battery life [16]. Recommended sample sizes for these calibration studies are between 50 and 100 tags [16].

Quantitative Data Comparison: Tag Placement Effects

Table 1: Impact of Vertical Tag Placement on a Killer Whale's Dorsal Fin

| Metric | Top Tag (Higher Placement) | Bottom Tag (Lower Placement) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Location Estimates | 540 | 245 |

| Rate (Locations per Hour) | 1.28 | 0.58 |

| Location Quality (% in Argos Class B) | ~50% | ~90% |

| Median Time Between Locations | 44.5 minutes | 70.5 minutes |

| Total Track Length | 1,338 km | 896 km |

| Average Speed | 3.16 km/h | 2.12 km/h |

Data sourced from a controlled experiment with two tags deployed on the same individual [37].

Table 2: Hydrodynamic Impact of Tags on Mako Sharks

| Tag Attachment Site | Shark Size | Increase in Drag | Additional Energetic Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fin | 2.95 m fork length | 17.6% - 31.2% | Not Quantified |

| Dorsal Musculature | >1.5 m fork length | Minimal | Minimal |

| Dorsal Musculature | 1 m fork length | 5.1% - 7.6% | ~7% of daily requirement |

Data derived from Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Comparative Tag Performance on a Single Animal

This methodology, used to isolate the effect of tag positioning, involves deploying two identical satellite tags at different vertical positions on the same animal [37].

- Tag Selection: Use two identical model tags.

- Deployment: Deploy both tags on the same individual, ensuring a meaningful vertical separation (e.g., 33 cm on a killer whale's dorsal fin). Record the precise location of each tag.

- Data Collection: Collect transmission data including the number of location estimates, their Argos quality classes, and the time intervals between locations over a simultaneous operational period.

- Path and Analysis: Reconstruct movement paths using a state-space model. Compare derived metrics such as cumulative track length, average speed, step lengths, and turning angles. Perform behavioral state analysis (e.g., Hidden Markov Models) on both tracks and compare the results.

Protocol 2: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Hydrodynamic Impact

This in silico protocol assesses the drag and energetic costs imposed by different tags [10].

- Geometry Creation: Develop accurate 3D digital models of the study animal (e.g., a mako shark) and the tags to be tested.

- Mesh Generation: Discretize the computational domain surrounding the geometry into millions of small control volumes to form a mesh.

- Parameter Setting: Define boundary conditions and fluid properties (e.g., water flow velocity, turbulence intensity). Use a steady-state solver like

simpleFoamin OpenFOAM and a turbulence model such as k-w-SST. - Simulation and Analysis: Run simulations for both tagged and untagged models across a range of realistic swimming speeds. Calculate the hydrodynamic forces, focusing on drag. Compare the results to quantify the percentage increase in drag and model the subsequent energetic implications for the animal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Telemetry Tagging Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Satellite Tags (e.g., SPOT) | Transmit animal location data to satellites when the antenna breaks the water's surface [38]. |

| Acoustic Tags | Emit coded signals detected by underwater receiver arrays, ideal for fine-scale movement studies in aquatic environments [16]. |

| Corrodible Bolts | Used in penetrative attachments; designed to corrode and release the tag after a predetermined time [38]. |

| Non-Penetrative Clamps/Braces | Attachment methods that minimize tissue damage by clamping onto the edge of a fin rather than penetrating it [38]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Enables virtual modeling of tag hydrodynamics to refine tag design and placement before physical deployment [10]. |

| State-Space Model (SSM) | A statistical framework to filter noise and estimate the true, underlying path of an animal from imperfect telemetry data [37]. |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | A statistical tool used to identify latent behavioral states (e.g., "foraging," "transit") from movement data [37]. |

Methodological Decision Workflow

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers implementing the innovative drone-based 'Tap-and-Go' telemetry tagging method. This methodology is designed to minimize animal disturbance as part of a broader thesis on reducing impacts in animal-borne telemetry research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Q: Our drone approach consistently triggers flight responses in avian species. What operational parameters should we adjust?

A: Flight responses are often tied to specific operational thresholds. We recommend the following adjustments based on species type:

| Species Type | Recommended Minimum Altitude | Recommended Approach Speed | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seabirds (e.g., Penguins) | 30-50 meters [39] | 20-25 km/h [39] | Gentoo penguins showed behavioral changes at 30m; Adélie penguins responded at 50m [39]. |

| Waterfowl on Land | > 40 meters [39] | 20-25 km/h [39] | Minimal reaction when drones maintained >40m distance during take-off; avoid direct overhead approaches [39]. |

| Terrestrial Mammals (e.g., Kangaroos) | > 30 meters [39] | Slow, predictable patterns | Fleeing rarely occurred above 30m altitude; vigilance was the primary response [39]. |

| Large Mammals (e.g., Elephants) | > 50 meters [39] | Slow, predictable patterns | Increased vigilance observed at distances of 50m and above [39]. |

Experimental Protocol for Parameter Validation:

- Baseline Observation: Record undisturbed animal behavior for 30 minutes prior to drone launch [1].

- Staged Approach: Begin drone operations at 100m altitude, decreasing in 10m increments every 5 minutes while recording behavior [39].

- Data Collection: Use the drone's onboard camera to document specific vigilance, flight, or aggression behaviors.

- Threshold Identification: Use breakpoint analysis on the behavioral record to identify the specific altitude or distance at which significant behavioral changes occur, similar to methodologies used in tag implantation recovery studies [1].

Q: We are observing significant behavioral changes post-tagging. How do we determine if this is a short-term effect or a long-term impact?

A: Differentiating between short-term stress and long-term impact is critical. Implement the following monitoring protocol:

| Metric | Monitoring Method | Baseline Comparison | Short-Term Indicator (e.g., 2-3 weeks) [1] | Long-Term Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Dive frequency, foraging time, activity patterns [1] | Pre-tagging data or control animals | Consistent reduction in foraging effort, shorter bouts [1] | Failure to return to baseline after 3-4 weeks |

| Physiology | Body temperature via bio-logger [1] | Pre-tagging temperature | Elevated body temperature (e.g., Δ=0.46°C) indicating immune response/inflammation [1] | Persistent elevation beyond recovery period |

| Recovery Timeline | Breakpoint analysis [1] | N/A | Return to baseline for Tb and behavior at ~14-18 days post-procedure [1] | No clear breakpoint identified |

Experimental Protocol for Impact Assessment:

- Pre-Tagging Baseline: Collect at least 7 days of archival data on behavior and physiology prior to any intervention [1].

- Continuous Post-Tagging Monitoring: Use the implanted telemetry tag or separate bio-loggers to collect data for a minimum of 30 days [1].

- Data Analysis: Perform a breakpoint analysis on the dive record and body temperature data to objectively identify the timeline for a return to baseline. Use linear mixed models to assess if recovery is influenced by covariates like reproductive status [1].

Troubleshooting Logic for Animal Disturbance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the primary factors that influence wildlife disturbance from drones, beyond just altitude? A: While altitude is a primary factor, disturbance is multi-faceted. Key influences include:

- Operational Factors: Flight speed, approach angle (direct overhead approaches are more disruptive), and proximity of take-off/landing [39].