Playing Dead to Stay Alive

The Scorpion's Ultimate Deception Tactic

By Science Insights, August 10, 2025

Article Navigation

Introduction: The Art of Disappearing While in Plain Sight

In the predator-prey arms race, some creatures fight with venom, others flee with speed—but a select few master the art of becoming invisible through absolute stillness. Thanatosis, or "death feigning," ranks among nature's most counterintuitive survival strategies. Imagine confronting a predator so dangerous that your best option is to roll over, go rigid, and play corpse. For scorpions like Tityus ocelote and Ananteris platnicki in Central America's rainforests, this isn't a last resort—it's a calculated gamble for survival. Recent research reveals how these arachnids deploy theatrical immobility to baffle predators, rewriting our understanding of scorpion behavior and evolution 1 8 .

Key Scorpion Facts

- Species: Tityus ocelote, Ananteris platnicki

- Location: Central American rainforests

- Defense: Thanatosis (death feigning)

- Discovery: First documented in 2022

The Science of Stillness: What Is Thanatosis?

Thanatosis (from Greek thanatos, meaning "death") describes a state of tonic immobility where animals mimic lifelessness. Unlike freezing—a temporary pause—thanatosis involves:

- Complete muscular rigidity

- Voluntary suppression of reflexes

- Dramatic body positioning (often belly-up)

- Non-responsiveness to physical provocation

In evolutionary terms, this behavior exploits predators' instincts: many hunters lose interest in motionless prey or avoid carrion due to disease risks. For small scorpions, it's a low-energy alternative to venomous combat—especially against adversaries resistant to their stings 1 .

Thanatosis vs Freezing

Comparison of defensive behaviors in arthropods

Central America's "Dead" Actors: A Groundbreaking Discovery

In 2022, biologists documented thanatosis in Costa Rican and Panamanian scorpions for the first time. The study focused on two species:

- Tityus ocelote: A dark buthid scorpion inhabiting tropical rainforests

- Ananteris platnicki: A tiny leaf-litter specialist (<3 cm) with an elongated tail 1 3

The Experiment: Testing the Death Act

Researchers collected wild specimens and observed their anti-predator responses through simulated attacks. Methodology included:

Provocation Protocol

- Gentle handling with forceps (mimicking predator contact)

- Placement in open terrariums to remove escape options

- Mechanical stimuli (antenna-like probes) during "death" state

Key Metrics Recorded

- Time to initiate thanatosis

- Duration of immobility

- Body posture specifics

- Response thresholds to touch

| Species | Initiation Time | Avg. Duration | Posture | Response to Touch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tityus ocelote | 2–5 seconds | 45–90 seconds | On back, legs curled | None |

| Ananteris platnicki | 1–3 seconds | 60–120 seconds | On back, tail flat | None |

Results showed both species consistently flipped onto their backs, adopting rigid poses indistinguishable from death. Even when prodded, they remained motionless for up to two minutes—an eternity for a small arthropod 1 8 .

Why Play Dead? The Survival Calculus

For Ananteris platnicki, thanatosis complements other defenses:

- Venom chemistry: Its venom shares components with Old World scorpions (Lychas, Isometrus), targeting ion channels—but producing it is metabolically costly 3 9 .

- Autotomy: These scorpions can self-amputate their tails to escape, sacrificing venom glands but surviving (a trait observed during venom extraction) 9 .

Thanatosis offers a middle ground: no physical sacrifice, minimal energy expenditure. As researcher Felipe Triana noted, "It's the ultimate bluff in habitats teeming with visual hunters like birds and spiders" 1 .

| Strategy | Energy Cost | Effectiveness | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venomous sting | High | Variable | Limited venom reserves |

| Tail autotomy | Extreme | High (escape) | Loss of venom, digestion |

| Thanatosis | Low | Moderate-High | Vulnerability if detected |

Defense Strategy Efficiency

Energy cost vs effectiveness of different defense mechanisms

An Evolutionary Enigma: Is This a Family Trait?

The study proposed a bombshell hypothesis: thanatosis may have deep roots in American buthid scorpions. Previously, the behavior was known only in:

- Tityus pusillus and T. cerroazul (Brazil)

- Liocheles australasiae (Asia)

- Scorpiops jendeki (China) 1

The discovery in T. ocelote and A. platnicki suggests convergent evolution—or a shared ancestral trait in the Buthidae family. Intriguingly, Tityus and Ananteris belong to ancient lineages that diverged as Gondwana fragmented, hinting at a 100-million-year-old behavioral "heirloom" 1 3 .

Evolutionary Tree of Thanatosis

Simplified phylogenetic tree showing scorpion species with thanatosis behavior (highlighted in red)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Decoding Scorpion Behavior

Field biologists rely on specialized tools to study thanatosis without disturbing natural behaviors:

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UV flashlights | Detect nocturnal scorpions (cuticle fluoresces) | Locating T. ocelote in leaf litter |

| Micro-forceps | Simulate predator attacks | Provoking thanatosis response |

| High-speed cameras | Record rapid initiation of immobility | Analyzing muscle contraction sequences |

| HPLC-mass spec | Analyze venom composition | Comparing venom profiles of feigning species 3 9 |

| Hygrometers | Monitor microhabitat humidity | Testing environmental triggers for thanatosis |

UV Detection

Scorpions fluoresce under UV light, making them easier to find at night.

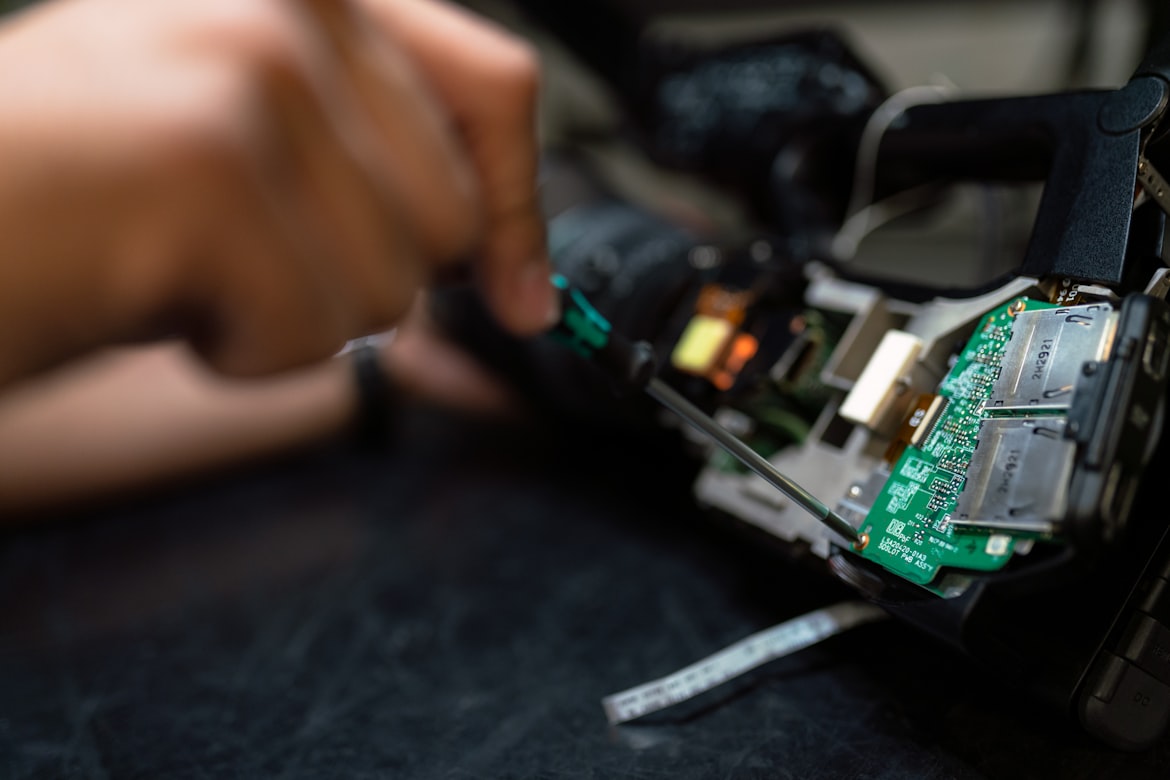

Precise Handling

Micro-forceps allow researchers to simulate predator attacks without harm.

Venom Analysis

Mass spectrometry reveals the complex chemistry of scorpion venom.

Conclusion: The Silent Drama Beneath Our Feet

The discovery of thanatosis in Central American scorpions illuminates a sophisticated survival strategy thriving in Earth's oldest ecosystems. For biologists, it raises profound questions: Did this behavior evolve once and spread through lineages, or emerge independently across continents? How do predators "see through" the ruse?

One truth is undeniable: in the shadows of rainforests, where life hinges on deception, sometimes the best move is no move at all. As we keep probing these ecosystems, the scorpion's death act reminds us that nature's most compelling dramas often unfold in stillness 1 8 .

Further Reading

- Triana et al. 2022 (Euscorpius No. 359)

- Kalapothakis et al. 2022 (Toxins of Amazonian Tityus)

- Krämer et al. 2022 (Sex-specific venom in Euscorpius)