Validating Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Methods, Applications, and Ethical Frameworks for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) validation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Validating Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Methods, Applications, and Ethical Frameworks for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) validation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles defining TEK and its distinction from Western science, examines quantitative and qualitative methodologies for documenting and assessing TEK, addresses critical ethical challenges including biopiracy and benefit-sharing, and evaluates frameworks for cross-cultural validation and integration with scientific data. The analysis synthesizes current research and case studies to offer a practical guide for ethically and effectively leveraging TEK in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Defining the Landscape: What is Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Why Validate It?

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) represents a cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs about the environment, developed through generations of intimate contact with specific landscapes by Indigenous Peoples and local communities [1]. Unlike informal observations, TEK is a sophisticated, place-based knowledge system empirically derived from long-term monitoring and adaptive response to environmental change [2]. This guide objectively compares TEK with Western scientific approaches, examining their respective methodologies, validation protocols, and performance in understanding ecological systems. The growing recognition within global environmental assessments that braiding TEK with Western science is essential for addressing biodiversity and climate crises underscores the practical importance of such comparative analysis [3].

Core Conceptual Comparison: TEK vs. Western Science

Foundational Principles and Characteristics

The comparison between TEK and Western science necessitates understanding their distinct philosophical foundations and methodological approaches. Rather than viewing these systems as mutually exclusive, contemporary frameworks employ the metaphor of "braiding" – combining distinct knowledge systems to create a stronger, more robust understanding while maintaining their individual integrity [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of TEK and Western Science

| Characteristic | Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) | Western Science |

|---|---|---|

| Epistemological Foundation | Relational, spiritual, and empirical; knowledge tied to place, culture, and intergenerational transmission [1] | Hypothesis-driven, mechanistic, and analytical; seeks universal principles independent of context [3] |

| Temporal Scale | Multi-generational (centuries to millennia); provides long-term baselines addressing Shifting Baseline Syndrome [3] | Typically short-term (years to decades); often lacks historical continuity beyond recorded data [3] |

| Methodology | Qualitative and quantitative observations through direct livelihood dependence; experimental through adaptive response [2] | Quantitative measurement; controlled experiments; statistical analysis; peer-reviewed publication [3] |

| Scope of Inquiry | Holistic; integrates ecological, cultural, spiritual, and social dimensions; focuses on relationships and connectivity [2] | Reductionist; tends to isolate variables for detailed study; specialized disciplinary approaches [3] |

| Validation System | Practical success in sustaining communities and ecosystems over generations; cultural verification [4] | Statistical significance; experimental replication; peer review; institutional validation [3] |

| Knowledge Transfer | Oral tradition, practical demonstration, rituals, and storytelling [1] | Formal education, published literature, institutional training [3] |

Conceptual Framework of Knowledge Braiding

The relationship between TEK and Western science can be understood as a braiding process where distinct knowledge systems maintain their integrity while creating stronger outcomes together. This conceptual framework illustrates the complementary strengths and the process of ethical engagement.

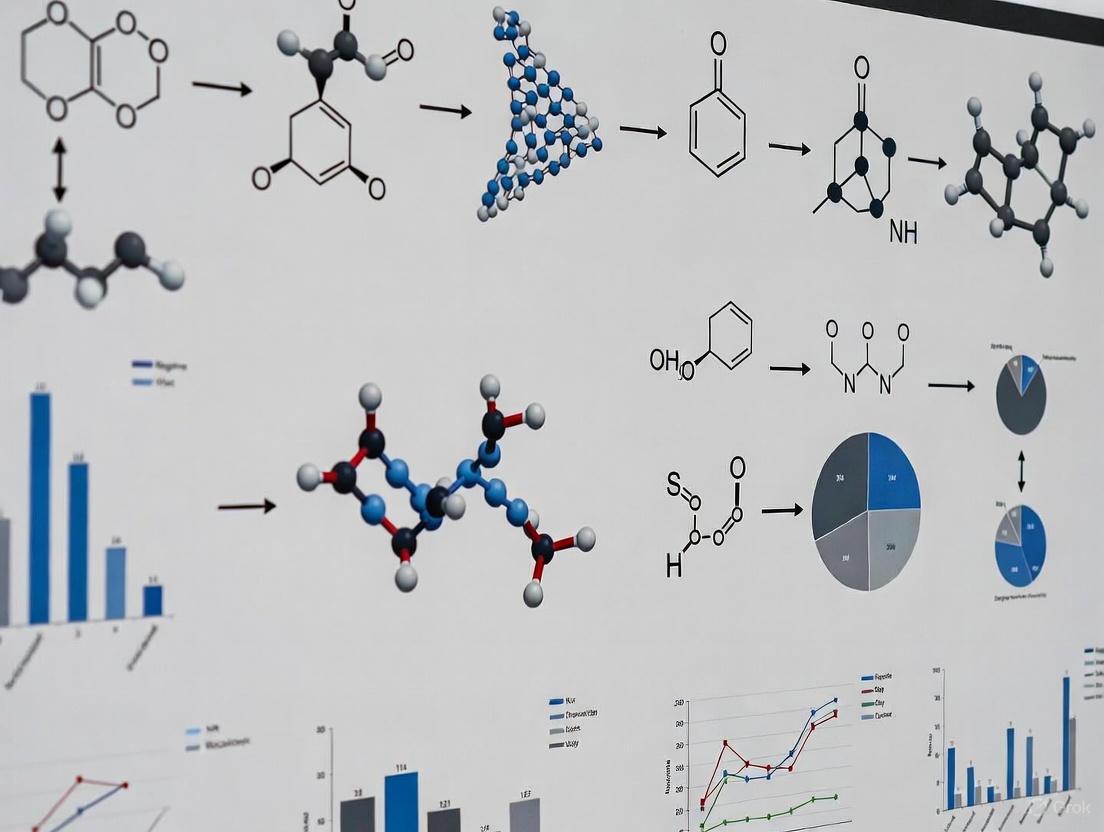

Diagram 1: Knowledge Braiding Conceptual Framework

Experimental Validation Protocols and Performance Data

Quantitative Assessment of TEK in Ecosystem Services Management

Recent research has developed methodological frameworks to quantitatively evaluate how TEK contributes to ecosystem management. A 2025 study in an Iranian semi-arid socio-ecosystem employed rigorous mixed-methods approaches to spatially link TEK, ecosystem services, and habitat quality [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Influence of TEK and Habitat Quality on Ecosystem Services

| Ecosystem Service Category | Key Service Examples | Most Influential Factor | Statistical Significance | Effect Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Services | Aesthetics, education, recreation, spiritual value | Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) | p < 0.05 | High |

| Provisioning Services | Beekeeping, medicinal plants, water yield, nursing function | Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) | p < 0.05 | High |

| Regulating Services | Gas regulation, soil retention, climate regulation | Habitat Quality | p < 0.05 | High |

| Supporting Services | Soil stability, nutrient cycling, biodiversity maintenance | Habitat Quality | p < 0.05 | High |

The study modeled eleven ecosystem services and found statistically significant variations in how different land covers deliver social-ecological quality and ecosystem services (p < 0.05). Structural Equation Modeling revealed that cultural and provisioning services showed particularly high synergy with TEK, suggesting TEK can serve as an effective proxy for assessing these services [2].

Validation Protocol: Integrated Social-Ecological Assessment

The experimental protocol for validating TEK in ecosystem management involves sequential phases that braid methodological approaches from both knowledge systems:

Diagram 2: TEK Validation Experimental Workflow

Climate Resilience Applications in Himalayan Communities

A 2025 assessment of TEK in the Indian Himalayan region documented traditional practices across elevation gradients (50-3300 m asl) and established their relevance to climate change adaptation [4]. The study evaluated TEK practices against modern climate-smart frameworks, finding that many traditional approaches in agriculture, soil, and natural resource management function as "triple-win" strategies, simultaneously supporting climate adaptation, resilience, and mitigation of greenhouse gases [4].

Table 3: Performance Assessment of Himalayan TEK Practices in Climate Resilience

| Management Sector | TEK Practice Examples | Climate Adaptation Benefit | Mitigation Co-benefit | Scientific Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Crop diversification, traditional irrigation, timing of planting | High (reduced climate vulnerability) | Medium (carbon sequestration in soils) | Partial validation |

| Forest Resources | Native species protection, non-timber forest product management | High (biodiversity conservation) | High (carbon storage) | Strong validation |

| Soil Management | Traditional terracing, organic amendments, erosion control | High (reduced soil loss) | Medium (carbon retention) | Moderate validation |

| Water Management | Spring rejuvenation, traditional water harvesting | Medium (drought resilience) | Low | Limited validation |

| Livestock Management | Transhumance, indigenous breed conservation | Medium (fodder security) | Low | Limited validation |

The Himalayan study revealed that while significant TEK documentation exists, landscapes remain understudied for their potential contributions to climate change adaptation, resilience, and mitigation strategies. The research identified a critical need for more scientific validation of TEK practices and integration with modern techniques to enhance their effectiveness [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Methodological Approaches for TEK Validation

Essential Methodological Frameworks and Protocols

Table 4: Research Toolkit for TEK Validation Studies

| Methodological Approach | Primary Function | Implementation Example | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Analyzes complex direct/indirect relationships between social-ecological variables and ecosystem services [2] | Testing pathways between TEK, habitat quality, and ecosystem service delivery | Ensure models reflect community understandings; avoid oversimplification |

| InVEST Model Suite | Quantifies and maps ecosystem services using spatial data; compatible with TEK layers [2] | Modeling water yield, soil retention, habitat quality alongside TEK data | Combine with participatory mapping; validate outputs with local knowledge |

| Participatory GIS | Geospatially documents TEK while maintaining community data sovereignty [2] | Mapping culturally significant sites, resource areas, traditional territories | Community control over sensitive spatial data; appropriate consent protocols |

| Two-Eyed Seeing Framework | Braids Indigenous and Western knowledge by viewing through both lenses [3] | Co-designing research questions and methodologies with knowledge keepers | Equity in decision-making; recognition of multiple knowledge authorities |

| Systematic Mapping Protocol | Comprehensively synthesizes evidence base on knowledge braiding methodologies [3] | Identifying knowledge clusters and gaps in TEK-Western science integration | Include grey literature and non-English sources; avoid exclusionary criteria |

Comparative Performance Analysis and Applications

Evidence-Based Outcomes of Knowledge Braiding

The performance of TEK in environmental management can be evaluated through specific case studies where its integration with Western science has produced measurable outcomes:

Forest Garden Management: Research on Indigenous-created forest gardens in the Pacific Northwest demonstrated they support more pollinators, more seed-eating animals, and more plant species than supposedly "natural" conifer forests. These gardens exhibited higher functional diversity – which captures an ecosystem's ability to feed animals and perform other ecological functions – despite 150 years without maintenance [1].

Medicinal Plant Validation: Investigation of Psychotria insularum, used in traditional Samoan medicine as matalafi, confirmed anti-inflammatory properties comparable to ibuprofen through rigorous laboratory analysis. This research, led by a native Samoan scientist, provided scientific validation for traditional healing practices while maintaining cultural context [1].

Freshwater Ecosystem Management: The systematic braiding of TEK with Western science addresses critical knowledge gaps in freshwater social-ecological systems, where conventional monitoring often fails to capture long-term trends and fine-scale dynamics. TEK provides essential historical baselines that counter Shifting Baseline Syndrome in these vulnerable ecosystems [3].

Performance Limitations and Research Gaps

Despite promising applications, several limitations affect both the validation and implementation of TEK:

- Documentation Gaps: Himalayan studies show disproportionate focus on agriculture and forest TEK with insufficient documentation of water and livestock management knowledge [4]

- Validation Challenges: Many TEK practices lack comprehensive scientific validation or integration with modern techniques to enhance their effectiveness [4]

- Methodological Barriers: Existing research often fails to capture the spatial dimensions of TEK or quantitatively link it to ecosystem service outcomes [2]

- Cultural Erosion: Accelerating loss of TEK due to cultural change and environmental disruption threatens this knowledge base before it can be documented or validated [4]

The comparative analysis demonstrates that TEK and Western science represent complementary rather than competing knowledge systems, each with distinctive strengths and limitations. TEK provides multi-generational place-based insights, addresses Shifting Baseline Syndrome through long-term ecological memory, and offers practical solutions refined through continuous adaptation [3]. Western science contributes rigorous validation protocols, statistical modeling capabilities, and technological innovations [2].

The most effective approach emerging from current research involves "braiding" these knowledge systems – maintaining their distinct integrity while combining them to create more robust understanding and management outcomes [3]. Future research priorities include developing standardized yet flexible validation protocols, addressing documentation gaps in underrepresented regions and knowledge domains, and establishing ethical co-production frameworks that recognize Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities as essential partners rather than mere informants [3].

This comparative guide provides researchers with methodological frameworks for designing TEK validation studies that respect cultural context while generating scientifically rigorous evidence. By applying these integrated approaches, the scientific community can more effectively leverage the full spectrum of human understanding to address complex environmental challenges.

Within the realm of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) validation research, community acceptance and historical continuity emerge as two foundational, non-empirical principles that affirm the legitimacy and reliability of knowledge systems developed by Indigenous and local communities. Unlike Western scientific validation, which prioritizes controlled experimentation and statistical reproducibility, TEK validation is deeply embedded in social and temporal processes [5]. This guide objectively compares these core principles, framing them as complementary mechanisms that together ensure the integrity, relevance, and resilience of knowledge over time.

Comparative Analysis of Core Principles

The following table provides a structured comparison of these two core validation principles, detailing their primary functions, mechanisms, and roles within Traditional Ecological Knowledge systems.

| Characteristic | Community Acceptance | Historical Continuity |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | Serves as a social verification mechanism, ensuring knowledge is relevant, applicable, and culturally appropriate [5]. | Establishes temporal resilience, demonstrating the knowledge's endurance and adaptive capacity across generations [5] [6]. |

| Primary Mechanism | Ongoing use and endorsement by the community through practices, social norms, and cultural institutions [5]. | Intergenerational transmission via oral histories, stories, ceremonies, and practical apprenticeship [7] [8]. |

| Key Actors | Knowledge holders, elders, healers, and the broader community whose practices endorse the knowledge [5]. | Elders as knowledge keepers and youth as learners, ensuring the unbroken chain of transmission [8]. |

| Role in TEK System | Functions as a quality control check grounded in collective experience and real-world application [9]. | Provides the narrative backbone that connects present practices to ancestral wisdom and historical identity [7] [6]. |

| Outcome of Validation | Knowledge is deemed pragmatically sound and socially legitimate for addressing community needs [5]. | Knowledge is perceived as cultially authentic and endowed with the authority of time [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Research

Research into these validation principles requires methodologies that are collaborative, respectful, and culturally sensitive. The following protocols outline a rigorous approach for studying these processes.

Protocol for Assessing Community Acceptance

Objective: To systematically document and evaluate the degree to which a body of Traditional Ecological Knowledge is accepted and validated within its community of origin.

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC): Prior to initiation, researchers must obtain FPIC from community governance bodies. This involves transparent discussions about the research goals, methods, potential impacts, and how findings will be used and shared [10] [5].

- Participatory Design: Form a research advisory committee comprising community elders, knowledge holders, and other members to co-design the study, ensuring cultural appropriateness and relevance [11].

- Data Collection:

- Semi-Structured Interviews: Conduct interviews with a representative sample of community members, including recognized experts and practicing individuals. Focus on understanding how knowledge is applied, who is recognized as a legitimate authority, and the social processes that reinforce its use [5].

- Participant Observation: Engage in long-term, respectful observation of community practices (e.g., resource harvesting, ceremonies) to see how knowledge is enacted and socially reinforced in daily life [8].

- Focus Groups: Facilitate discussions to explore collective understanding and identify points of consensus or divergence regarding specific knowledge areas [9].

- Data Analysis: Employ qualitative thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns related to social approval, practical application, and the role of cultural institutions in upholding the knowledge [12].

Protocol for Establishing Historical Continuity

Objective: To trace the lineage and persistence of specific traditional knowledge practices across multiple generations.

- Ethical Review and Engagement: Adhere to the principles of Indigenous sovereignty and decolonizing methodologies. Recognize that the community has the ultimate authority over its historical narrative and knowledge [5].

- Intergenerational Knowledge Mapping:

- Life History Interviews: Record detailed narratives from elders, focusing on their acquisition of knowledge from previous generations and its subsequent application throughout their lives [8].

- Documentation of Oral Transmission Channels: Systematically record the stories, songs, ceremonies, and metaphors used to transmit complex ecological knowledge, analyzing their consistency and core principles over time [5] [8].

- Cross-Referencing with Archival Records: Where they exist and are accessible, consult historical documents, ethnographies, and missionary records to identify references to the knowledge or practice in question, thus creating a triangulated historical record [6].

- Validation through Resilience: Analyze how the knowledge has been adapted to historical disturbances (e.g., climate shifts, colonization) while retaining its core identity, demonstrating its dynamic yet continuous nature [7] [8].

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic, interconnected relationship between Community Acceptance and Historical Continuity in validating Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Engaging in research on TEK validation requires specific "reagents" and tools that are often intangible and relational, rather than purely material. The table below details these essential components.

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Validation Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Review Protocols | Ensures research respects Indigenous sovereignty, rights, and follows the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) [10] [5]. | Must be developed in partnership with community governance structures, not just institutional review boards. |

| Collaborative Frameworks | Establishes equitable partnerships for co-designing research questions, methodologies, and data interpretation [11]. | Shifts the role of the external researcher from an extractive expert to a collaborative partner. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | Aids in the systematic coding and thematic analysis of interview transcripts, field notes, and oral histories. | Researchers must ensure that the codes and categories reflect emic (insider) perspectives and are validated by community collaborators. |

| Digital Audio/Video Recorders | Used to document oral histories, ceremonies, and practical demonstrations with high fidelity for archival and analysis purposes [8]. | Ownership, access, and storage of these records must be governed by agreements that prioritize community control and data sovereignty [10]. |

| Participatory Mapping Tools | Allows communities to spatially document land use, sacred sites, and ecological changes, linking knowledge to place [8]. | Integrates spatial data with qualitative narratives, reinforcing the connection between knowledge and its geographical context. |

Community acceptance and historical continuity are not merely alternative validation criteria but are sophisticated, rigorous, and interdependent systems for establishing the legitimacy of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Community acceptance provides a real-time, social proof check, while historical continuity provides the longitudinal evidence of the knowledge's resilience and value. A robust research approach recognizes that these principles are most powerful when studied together, as they form a virtuous cycle: community acceptance ensures knowledge is transmitted, and successful transmission across generations is, in itself, a powerful form of validation. Effective validation research in this field therefore necessitates a shift from a purely extractive model to one of co-creation, respecting the sovereignty and intellectual property of Indigenous peoples while working to bridge epistemological worlds [5] [11].

Practical Application and Environmental Harmony as Evidence

The validation of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) increasingly relies on the intentional braiding of Indigenous understanding with Western scientific methodologies [3]. This approach is not merely about integrating one knowledge system into another, but about bringing together two distinct but complementary systems to create a stronger, more robust understanding for management action [3]. In the context of drug discovery and natural product research, this braiding offers powerful validation frameworks that honor both practical application and environmental harmony.

Ecosystem services management embodies this participatory, indigenous-based approach by combining ecological assessments with indigenous knowledge, contributing to sustainable utilization of ecosystem services [2]. This framework recognizes that cultural, provisioning, regulatory, and supporting services show high synergy with social-ecological quality, suggesting that social-ecological quality can be an effective proxy for ecosystem services, particularly cultural services [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated approach provides a more comprehensive validation paradigm that respects both empirical evidence and traditional wisdom.

Methodological Framework: Comparative Approaches for Knowledge Validation

Experimental Design for TEK Validation

Validating traditional ecological knowledge requires sophisticated methodological frameworks that respect both indigenous and scientific paradigms. The braiding of TEK with Western science creates powerful synergies, particularly in data-scarce regions, by addressing common gaps in Western science through crucial insights into ecological history, population trends, and sustainable practices [3]. This pluralistic approach allows for more robust validation of natural products and their therapeutic applications.

Critical to this process is the recognition of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) as essential partners and co-producers of knowledge, not merely as informants [3]. Effective validation methodologies therefore incorporate ethical engagement protocols that ensure equitable participation and respect for cultural context. The systematic mapping of braiding methodologies provides researchers with a comprehensive evidence base for designing validation studies that are both scientifically rigorous and culturally appropriate [3].

Data Validation and Corroboration Protocols

In computational and natural product research, the concept of "experimental validation" requires careful consideration. Rather than viewing computational methods as requiring validation through traditional experiments, a more appropriate framework involves orthogonal corroboration using multiple independent methods [13]. This approach recognizes that both computational and experimental methods have strengths and limitations, and combining them provides more reliable evidence than either approach alone.

Data validation processes examine both quality and accuracy of collected data before processing and analysis [14]. For TEK-based research, this includes validating data through clear and objective questions in surveys, bullet-proofing multiple-choice questions, and setting standard parameters for data collection [14]. The validation process ensures robust datasets, provides clearer pictures of data patterns, increases result accuracy, mitigates risks of incorrect hypotheses, and enhances reproducibility of findings [14].

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Assessment of Ecosystem Services

Structured Data Comparison of Social-Ecological Quality Indicators

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment of Ecosystem Services and Social-Ecological Quality Relationships

| Ecosystem Service Category | Specific Ecosystem Service | Primary Influencing Factor | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Synergy with Social-Ecological Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Services | Aesthetics, Education, Recreation | Traditional Ecological Knowledge | p < 0.05 [2] | High [2] |

| Provisioning Services | Beekeeping, Medicinal Plants, Water Yield | Traditional Ecological Knowledge | p < 0.05 [2] | High [2] |

| Regulating Services | Gas Control, Soil Retention | Habitat Quality | p < 0.05 [2] | High [2] |

| Supporting Services | Soil Stability, Nursing Function | Habitat Quality | p < 0.05 [2] | High [2] |

The structured comparison of ecosystem services reveals clear patterns in how different services relate to social-ecological quality indicators. Research demonstrates that land covers vary significantly in their capacity to deliver social-ecological quality and ecosystem services, with distinct factors influencing different service categories [2]. This quantitative assessment provides researchers with a framework for evaluating the complex relationships between ecological factors and traditional knowledge systems.

Methodological Comparison for Knowledge Braiding

Table 2: Research Methodologies for Braiding Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western Science

| Research Methodology | Primary Application | Data Collection Techniques | Analytical Approaches | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Linking of Ecosystem Services | Mapping social-ecological relationships | Field data collection, GIS techniques, Indigenous community surveys [2] | InVEST model, Structural Equation Modeling [2] | Spatial maps of ecosystem services, Relationship pathways [2] |

| Systematic Review Protocol | Global synthesis of freshwater management | Database searches, Grey literature review, Snowballing search [3] | Bibliographic coding, Typology development, Interactive visualization [3] | Database of braiding methodologies, Knowledge gap analysis [3] |

| Orthogonal Corroboration | Computational model verification | High-throughput technologies, Low-throughput gold standard methods [13] | Comparative analysis, Statistical validation | Reproducible findings, Enhanced confidence in results [13] |

The comparative analysis of methodological approaches reveals diverse strategies for braiding traditional ecological knowledge with Western science. Each methodology offers distinct advantages for different research contexts, from spatial mapping to systematic reviews and orthogonal corroboration. Understanding these methodological options enables researchers to select appropriate approaches for their specific validation needs.

Visualization Frameworks: Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Knowledge Braiding Methodology Workflow

Ecosystem Services Assessment Protocol

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for TEK Validation Research

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Tools for Traditional Ecological Knowledge Validation

| Research Tool Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Analysis Tools | GIS Software, InVEST Model [2] | Spatial mapping and linking of ecosystem services with traditional knowledge | Quantifying distribution of ecosystem services and habitat quality [2] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Structural Equation Modeling packages [2] | Analyzing direct and indirect relationships between social-ecological variables | Testing complex pathways between TEK, habitat quality, and ecosystem services [2] |

| Data Collection Platforms | Community survey instruments, Field data collection protocols [2] | Systematic documentation of traditional ecological knowledge | Recording indigenous community preferences and ecological knowledge [2] |

| Validation Methodologies | Orthogonal corroboration approaches [13] | Cross-verifying findings through independent methods | Enhancing confidence in computational models and traditional knowledge [13] |

| Systematic Review Protocols | CEE Guidelines, ROSES Reporting Standards [3] | Comprehensive evidence synthesis | Mapping global evidence base for knowledge braiding methodologies [3] |

The research toolkit for validating traditional ecological knowledge requires both technical tools for data analysis and methodological frameworks for ethical engagement. Spatial analysis tools enable researchers to map the distribution of ecosystem services and their relationship to traditional knowledge, while statistical packages help analyze complex relationships between variables. Critically, the toolkit must also include protocols for community engagement and knowledge documentation that respect indigenous perspectives and ensure equitable participation in the research process.

The braiding of traditional ecological knowledge with Western scientific approaches offers a robust framework for validation that honors both empirical evidence and cultural wisdom. This integrated approach demonstrates that cultural and provisioning services are most significantly influenced by traditional ecological knowledge, while regulating and supporting services are primarily affected by habitat quality [2]. This nuanced understanding enables more effective and sustainable management of ecosystem services, including those relevant to drug discovery from natural products.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated validation framework provides a comprehensive approach that addresses both practical application and environmental harmony. By recognizing Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities as essential partners in knowledge co-production [3], and by utilizing orthogonal corroboration to enhance confidence in research findings [13], this approach represents a transformative pathway for validating traditional knowledge while advancing scientific understanding. The result is a more equitable, effective, and sustainable paradigm for research that serves both human and ecological communities.

The Critical Role of TEK in Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Management

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) represents a cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs about the relationship of living beings with one another and their environment, handed down through generations by cultural transmission [15]. As global biodiversity declines at unprecedented rates—with monitored freshwater vertebrate populations plummeting by an average of 83% since 1970 [3]—the integration of TEK with Western science has become increasingly recognized as essential for effective conservation. This guide provides a comparative analysis of TEK and conventional scientific approaches, examining their respective methodologies, applications, and outcomes in biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. We present experimental data and frameworks that demonstrate how braiding these knowledge systems creates more robust, equitable, and effective conservation strategies.

Understanding the Knowledge Systems: TEK vs. Western Science

Defining the Frameworks

Traditional Ecological Knowledge is a place-based, cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs about the environment held by Indigenous Peoples and local communities [3] [15]. Unlike Western science, which often operates through hypothesis-driven methodologies, TEK is rooted in social institutions, worldviews, and spiritual relationships with nature, assimilated through observation, demonstration, imitation, and learning by doing [15]. The concept of "braiding" knowledge systems, as opposed to mere integration, emphasizes maintaining the distinct integrity of each system while combining them to create stronger understanding [3].

Table: Comparative Characteristics of TEK and Western Science

| Characteristic | Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) | Western Scientific Knowledge |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission | Cultural transmission through generations | Formal education and publication |

| Methodology | Observation, imitation, learning by doing | Hypothesis testing, controlled experiments |

| Temporal Scope | Long-term, multi-generational | Often short-term, limited funding cycles |

| Spatial Scope | Place-based, specific to local ecosystems | Seeks universal principles, generalizable |

| Quantification | Qualitative, experiential | Primarily quantitative, statistical |

| Worldview | Holistic, spiritual connection to nature | Often mechanistic, materialist |

| Validation | Practical success, cultural continuity | Peer review, statistical significance |

Global Policy Context

The foundational mandate for knowledge braiding was established at the landmark 1992 Rio Earth Summit, where Agenda 21 called for recognizing and strengthening the role of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge [3]. This was legally codified in the Convention on Biological Diversity's Article 8(j), which obligates parties to respect and preserve traditional knowledge [3]. More recently, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework's Target 22 requires the full and effective participation of IPLCs and the integration of their knowledge [3].

Experimental Evidence: Comparative Methodologies and Outcomes

Ecosystem Services Assessment in Iranian Semi-Arid Ecosystems

A 2025 study conducted in Bardsir County, Iran, provides compelling quantitative evidence of TEK's role in managing ecosystem services [2]. Researchers employed an integrated methodology to spatially link ecosystem services, TEK, and ecosystem quality for optimal management.

Table: Experimental Protocol for TEK and Ecosystem Services Assessment

| Research Component | Methodology | Data Collection Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem Services Quantification | Field data collection, InVEST model, GIS techniques | Field sampling, spatial analysis |

| Traditional Ecological Knowledge Documentation | Community surveys, participatory mapping | Interviews, focus groups, spatial documentation |

| Social-Ecological Relationships | Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Statistical analysis of direct/indirect relationships |

| Service Categorization | Categorized 11 ecosystem services across provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural classes | Field measurements, community input, model outputs |

Key Findings:

- The most significant component influencing cultural and provisioning services was TEK, while habitat quality most significantly influenced supporting and regulating services [2].

- Cultural, provisioning, regulatory, and supporting services showed high synergy with social-ecological quality, suggesting that social-ecological quality can be an effective proxy for ecosystem services [2].

- The study presented a comprehensive model for ecosystem services management integrated with TEK of local communities to provide realistic and feasible solutions for sustainable exploitation of natural resources [2].

Freshwater Ecosystem Management: Systematic Mapping Protocol

A systematic map protocol developed to evaluate methodologies for braiding TEK with Western science in freshwater social-ecological systems reveals critical frameworks for comparative analysis [3]. This research addresses the global freshwater biodiversity crisis, where one in four assessed freshwater species faces extinction [3].

Experimental Framework:

- Primary Question: What is the evidence base for methodologies that braid TEK of Indigenous and local communities with Western science in freshwater social-ecological systems? [3]

- Search Strategy: Multi-layered approach across bibliographic databases, grey literature, and snowballing searches [3]

- Analysis Dimensions: Bibliographic/geographic characteristics, ecological context, knowledge-holding communities, type of TEK braided, purpose and stage of braiding, tools/techniques/ethics, and directionality/barriers/enablers [3]

Biodiversity Assessment in Hydropower-Regulated Rivers

Research on Norwegian rivers demonstrates how conventional Western science indices can fail to detect ecological impacts without appropriate methodologies [16]. In a study of a hydropower-regulated river, the commonly used Average Score Per Taxon (ASPT) index showed "Good" to "High" status for all samples, while an alternative Intercalibrated Benthic Invertebrate Biodiversity Index (IBIBI) returned "Bad" to "Moderate" status using the same data [16].

Table: Comparison of Freshwater Bioassessment Indices

| Index | Sensitivity | Taxonomic Level | Primary Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASPT (Average Score Per Taxon) | Low for hydro-morphological pressure | Family-level | Organic pollution | Poor performance in regulated rivers |

| IBIBI (Intercalibrated Benthic Invertebrate Biodiversity Index) | High for multiple pressures | Species-level | General ecological status | Requires species-level identification |

| DNA-Based Methods | Potentially highest | Species-level via genetic markers | Comprehensive biodiversity assessment | Standardization and cost challenges |

Methodological Protocols for TEK Integration

Documentation and Validation Frameworks

Systematic Documentation Protocol:

- Community Engagement: Establish ethical collaboration frameworks with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) as essential partners and co-producers of knowledge, not merely as informants [3]

- Knowledge Recording: Employ multiple methods including interviews, focus groups, participatory mapping, and seasonal calendars [2] [15]

- Spatial Integration: Use GIS techniques to document and integrate traditional ecological information with habitat quality assessments [2]

- Validation: Combine statistical analysis (e.g., Structural Equation Modeling) with community validation processes [2]

Forms of TEK Documented in African Conservation:

- Taboos and totems

- Customs and rituals

- Rules and regulations

- Metaphors and proverbs

- Traditional protected areas (social institutions)

- Local knowledge of plants, animals, and landscapes

- Resource management systems [15]

Braiding Methodologies: From Integration to Co-Production

The systematic map protocol identifies various methodologies for braiding TEK with Western science [3]:

- Guiding Approaches: Philosophical stances for collaboration, such as co-production

- Conceptual Frameworks: Structured processes that guide braiding, such as Two-Eyed Seeing

- Specific Models: Tangible tools or outputs, such as participatory maps [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Methods for TEK Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Structured & Semi-structured Interviews | Document TEK practices and perceptions | Qualitative data collection from knowledge holders |

| Participatory GIS Mapping | Spatial documentation of TEK | Mapping resource use, significant sites, ecological observations |

| InVEST Model | Ecosystem services quantification | Modeling service distribution and quantifying habitat quality |

| DNA Metabarcoding | Biodiversity assessment | Species identification from environmental samples |

| Structural Equation Modeling | Analysis of social-ecological relationships | Testing direct/indirect relationships between variables |

| Seasonal Calendars | Temporal documentation of TEK | Recording seasonal patterns in resource availability and use |

Comparative Outcomes and Synergies

Addressing Knowledge Gaps and Limitations

TEK addresses critical gaps in conventional scientific monitoring by providing:

- Historical Baselines: Long-term ecological insights that predate scientific monitoring [3]

- Fine-Scale Resolution: Localized knowledge of ecological dynamics [3]

- Cost-Effective Monitoring: Continuous observation through daily practices [15]

- Cultural Context: Understanding of spiritual and symbolic dimensions of conservation [15]

Conversely, Western science provides:

- Standardized Methodologies: Reproducible across different contexts [16]

- Quantitative Rigor: Statistical validation of patterns [2]

- Technological Innovation: Advanced monitoring and analysis tools [16]

- Policy Integration: Frameworks compatible with governmental systems [3]

Barriers and Enablers in Knowledge Braiding

Documented Barriers:

- Changing cultural mores and practices (including Christianity and Islam) [15]

- Formal education systems that marginalize Indigenous knowledge [17]

- Modernization and new political dispensations [15]

- Power imbalances in research relationships [3]

- Incompatible worldviews and validation criteria [3] [15]

Critical Enablers:

- Ethical collaboration frameworks that recognize IPLCs as essential partners [3]

- Bioregional approaches that ground learning in space and place [17]

- Integration of TEK into education systems [17]

- Policy frameworks that mandate TEK inclusion [3]

- Flexible methodologies that respect different knowledge systems [3]

The experimental evidence and comparative analysis presented demonstrate that TEK provides indispensable insights and methodologies for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. The most effective approaches braid TEK with Western science, creating synergistic relationships that enhance both understanding and application. The critical finding across studies is that different knowledge systems excel in different domains—TEK particularly influences cultural and provisioning services, while Western science more strongly informs regulating and supporting services assessment [2].

Future conservation efforts must move beyond token integration toward genuine co-production of knowledge, recognizing that biodiversity conservation is not merely a scientific challenge but a socio-ecological imperative that requires multiple ways of knowing. As global biodiversity declines continue, the braiding of Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western science offers a transformative pathway toward more effective, equitable, and sustainable ecosystem management.

The growing complexity of global environmental challenges, from biodiversity loss to climate change, has intensified the need for robust knowledge systems to inform sustainable solutions. Within this context, two distinct ways of understanding the natural world have gained prominence: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Western Scientific Frameworks. TEK refers to the cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs concerning the relationship of living beings with one another and with their environment, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission [18] [19]. In contrast, Western science is characterized by its emphasis on systematic observation, controlled experimentation, and rigorous analysis to establish universal principles and laws governing the natural world [20]. This guide objectively compares the performance and epistemological foundations of these two knowledge systems within the context of environmental research and validation.

Foundational Epistemological Contrasts

The core differences between TEK and Western science stem from their fundamental epistemological foundations—their theories of what constitutes knowledge and how it is acquired and validated.

Table 1: Foundational Epistemological Contrasts

| Aspect | Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) | Western Scientific Frameworks |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Epistemology | Relational, situated, and culturally embedded knowledge [20] | Historically Cartesian and Newtonian, separating mind from matter [20] |

| Nature of Reality | Interconnected web of relationships; humans as integral part of nature [20] | Seeks objective knowledge by distancing the knower from the known [20] |

| Primary Validation Method | Practical application and long-term success within community [20] | Peer review, replication of experiments, statistical significance [18] |

| Knowledge Transmission | Oral traditions, stories, songs, ceremonies, and practical demonstration [20] | Formal education, written documentation, and peer-reviewed publications [20] |

| Temporal Orientation | Long-term perspectives informed by generations of experience [20] | Often operates within project-based timeframes [20] |

These epistemological differences manifest in distinct methodological approaches. TEK employs methodologies deeply rooted in observation, participation, and intergenerational learning, where knowledge is refined through continuous feedback loops between practice and observation [20]. Western scientific methodology emphasizes controlled experiments, hypothesis testing, and variable manipulation to isolate cause-and-effect relationships [20]. The concept of objectivity also differs significantly: while Western science strives for objectivity by minimizing observer bias, TEK acknowledges the inherent subjectivity of human experience and the situatedness of knowledge [20].

Comparative Performance in Applied Contexts

Both knowledge systems demonstrate significant efficacy in specific applied contexts, with their performance varying according to the nature of the environmental challenge and social-ecological context.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Applied Contexts

| Application Area | TEK Performance & Evidence | Western Science Performance & Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem Management | High performance in social-ecological quality; most significant factor influencing cultural and provisioning services [2] | High performance in supporting and regulating services; most significant factor is habitat quality [2] |

| Climate Resilience | Enables indigenous communities to preserve/manage resources under diverse environmental conditions; forms foundation for climate-resilient villages [4] | Provides analytical tools, technological innovations, and framework for understanding global environmental processes [4] [20] |

| Biodiversity Conservation | "Forest gardens" show higher functional diversity (more pollinators, seed-eating animals, plant species) than surrounding coniferous forests [1] | Quantitative assessments of habitat quality and species population trends; InVEST model for mapping habitat quality [2] |

| Medical/Pharmaceutical Applications | Traditional Samoan remedy "matalafi" (using Psychotria insularum) confirmed to have anti-inflammatory properties similar to ibuprofen [1] | Clinical trials and laboratory analysis to identify active compounds and validate biochemical mechanisms [1] |

| Agricultural Systems | Balinese water temple networks managed sustainable rice production for centuries through complex ecological understanding [18] | Mechanistic analysis of pest vulnerabilities and monocropping impacts [18] |

A study from the Iranian semi-arid socio-ecosystem demonstrated that land covers varied significantly in their capacity to deliver both social-ecological quality and ecosystem services (p < 0.05) [2]. The research found that cultural, provisioning, regulatory, and supporting services showed high synergy with social-ecological quality, suggesting that social-ecological quality can be an effective proxy for ecosystem services, particularly cultural services [2]. Furthermore, the most significant component influencing cultural and provisioning services was TEK, while habitat quality was the most significant factor influencing supporting and regulating services [2].

Experimental Protocols for Knowledge Validation

TEK Documentation and Integration Protocol

The protocol for documenting and integrating TEK follows a participatory, community-based approach that respects Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. Prior informed consent is obtained through continuous consultation with community elders and knowledge holders, following established ethical guidelines for working with Indigenous communities [3]. Data collection employs semi-structured interviews, participatory mapping, and seasonal calendar development conducted in local languages [2] [3]. Validation occurs through triangulation across multiple knowledge holders and cross-verification with historical and archaeological records [2]. The integration phase uses spatial modeling techniques, such as GIS, to overlay TEK with scientific data layers, creating composite maps that visualize the convergence and divergence of knowledge systems [2]. Finally, peer review by community members ensures the accurate representation of knowledge before publication or application in management decisions [3].

Western Scientific Experimental Protocol

The Western scientific protocol for ecosystem assessment employs standardized, quantitative approaches designed for reproducibility and statistical validation. Hypothesis formulation establishes testable predictions based on existing theoretical frameworks [2]. Experimental design implements controlled comparisons, randomization, and replication, potentially using factorial designs like those pioneered by Ronald Fisher to test multiple variables simultaneously [21]. Data collection utilizes standardized sampling protocols, remote sensing technologies, and sensor networks to ensure consistent, comparable measurements across temporal and spatial scales [2]. Statistical analysis employs parametric or non-parametric tests to determine significance, with particular attention to power analysis to ensure adequate sample sizes [2]. Model validation uses independent datasets to test predictive accuracy, with uncertainty quantified through confidence intervals or Bayesian methods [2]. Finally, peer review through scientific journals provides external validation before knowledge is incorporated into policy or management [20].

Diagram 1: Knowledge Validation Workflows: TEK vs Western Science

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Integrated Knowledge Systems

| Research Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Knowledge System |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | Framework for open-ended questioning that respects cultural protocols while ensuring comprehensive data collection | TEK Documentation |

| Participatory Mapping Materials | Physical or digital tools allowing community members to spatially document land use, sacred sites, and resource areas | TEK Documentation |

| GIS (Geographic Information Systems) | Digital platform for layering different knowledge types and identifying spatial patterns and relationships | Integration |

| InVEST Model | Software suite for mapping and valuing ecosystem services and habitat quality | Western Science |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Programming environments for quantitative analysis, significance testing, and data visualization | Western Science |

| Structured Survey Instruments | Standardized questionnaires ensuring consistent, comparable data across sites and populations | Western Science |

| Ethical Review Protocols | Guidelines ensuring free, prior, and informed consent and equitable knowledge co-production | Integration |

Knowledge Braiding: An Integrated Approach

The most promising applications emerge when these knowledge systems are "braided" together, creating a stronger, more comprehensive understanding than either approach could achieve alone [3]. Unlike "integration," which can imply assimilation of one system into another, braiding suggests that both TEK and Western science retain their distinct integrity while combining to create more robust management outcomes [3]. This approach is increasingly recognized by global bodies like IPBES as essential for achieving the transformative change needed to address the biodiversity crisis [3].

Structural Equation Modeling in an Iranian semi-arid socio-ecosystem has demonstrated a suite of direct and indirect relationships between social-ecological variables and ecosystem services [2]. This research presented a comprehensive model for ecosystem services management integrated with TEK of local communities to provide realistic and feasible solutions for sustainable exploitation of natural resources [2].

Diagram 2: Knowledge Braiding for Enhanced Environmental Solutions

TEK and Western scientific frameworks represent distinct yet complementary approaches to understanding ecological systems. TEK offers holistic, place-based, and value-laden perspectives grounded in long-term experience and community knowledge, proving particularly valuable for cultural services, provisioning services, and climate adaptation [2] [4] [20]. Western science provides reductionist, quantitative, and objective frameworks emphasizing experimentation and universal principles, demonstrating particular strength in supporting and regulating services and technological innovation [2] [20]. Rather than viewing these systems as competing, researchers and policymakers are increasingly recognizing the power of braiding them together to address complex environmental challenges. This approach combines the long-term observational capacity and cultural embeddedness of TEK with the analytical precision and technological capabilities of Western science, creating more effective, equitable, and sustainable outcomes than either system could achieve alone [3].

From Theory to Practice: Methods for Documenting and Applying TEK in Research

Ethnobotanical Surveys and Ethnopharmacology in Drug Discovery

Ethnobotanical surveys and ethnopharmacology serve as critical interdisciplinary bridges, connecting the rich tapestry of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) with systematic scientific discovery processes. This approach provides a strategically valuable starting point for identifying bioactive plant compounds with therapeutic potential, significantly narrowing the search from thousands of plant species to those with documented human use [2] [22]. The World Health Organization notes that traditional medicine remains deeply embedded in healthcare, particularly for marginalized communities with limited access to conventional medical systems [23]. This field operates on the premise that plants used extensively within traditional healing systems over generations have a higher probability of yielding biologically active compounds, thus representing a pre-filtered library for pharmacological investigation [24] [25].

The process embodies what some scholars term "braiding" knowledge systems—bringing together distinct but complementary knowledge systems where both TEK and Western science retain their distinct integrity while combining to create a more robust understanding [3]. This braiding creates a powerful synergy for discovery, particularly because TEK can offer crucial insights into ecological history, sustainable practices, and therapeutic applications that might otherwise be missed in conventional screening approaches [3] [4]. The ethical and effective engagement in this field requires recognizing Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) as essential partners and co-producers of knowledge, not merely as informants [3].

Methodological Frameworks: Quantitative Approaches in Ethnobotanical Surveys

Core Ethnobotanical Indices and Their Applications

Ethnobotanical surveys employ rigorous quantitative methodologies to transform observational and interview data into statistically analyzable information, enabling researchers to identify plant species with the highest potential for pharmacological success. Table 1 summarizes the key quantitative indices that form the foundation of systematic ethnobotanical research.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Indices in Ethnobotanical Surveys

| Index Name | Formula | Application in Drug Discovery | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use Value (UV) | ( UV = \frac{\sum U_i}{N} ) | Identifies species with the most diverse therapeutic applications | Higher values indicate greater diversity of uses per species [23] |

| Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) | ( ICF = \frac{N{ur} - Nt}{N_{ur} - 1} ) | Pinpoints plants with high consensus for specific disease categories | Values close to 1 indicate high consensus for treating specific ailments [26] |

| Fidelity Level (FL) | ( FL = \frac{N_p}{N} \times 100 ) | Highlights species preferred for specific therapeutic purposes | Higher percentages indicate specialized use for particular conditions [23] [24] [26] |

| Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) | ( RFC = \frac{FC}{N} ) | Measures cultural prevalence and recognition of a plant's utility | Higher values indicate wider recognition within the community [23] [24] |

| Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI) | ( BEI = \frac{ms}{Sg} + \frac{mc}{N} \times \frac{Sg}{S_t} ) | Compares overall ethnobotanical knowledge richness between groups | Higher values indicate richer ethnobotanical knowledge [27] |

These quantitative approaches provide data amenable to hypothesis testing, statistical validation, and comparative analysis, moving the field beyond descriptive narratives [27] [22]. For instance, the Fidelity Level (FL) has been effectively applied in studies documenting traditional medicinal plants, where Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. received a 97% FL for treating severe headaches, strongly indicating its therapeutic potential for this specific condition [26]. Similarly, the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) helps researchers identify disease categories with the most consistent traditional treatment knowledge; a study of 115 medicinal plant species found the highest ICF (0.92) for gastrointestinal diseases, suggesting well-developed traditional knowledge in this therapeutic area [26].

The Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI): A Novel Comparative Tool

A recent methodological advancement is the Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI), designed to comprehensively compare general ethnobotanical knowledge between two or more human groups [27]. Unlike previous indices that focus on specific plant uses, the BEI complexly combines several crucial factors: (1) the total number of species reported by all participants in a particular group ((Sg)), (2) the mean number of species reported per participant in that group ((ms)), (3) the mean number of citations per species in that group ((mc)), and (4) the total number of species reported by all compared groups in the study ((St)) [27].

The BEI is particularly valuable for cross-cultural comparisons or for assessing knowledge retention within the same community across different time periods, age groups, or genders. Its formula, ( BEI = \frac{ms}{Sg} + \frac{mc}{N} \times \frac{Sg}{S_t} ), generates values typically ranging between 0 and 2, with higher values representing richer ethnobotanical knowledge [27]. This index addresses a significant methodological gap in ethnobotany by enabling systematic comparison of overall knowledge richness rather than just specific plant uses.

Experimental Protocols: From Field Documentation to Laboratory Validation

Standardized Ethnobotanical Data Collection Workflow

The transition from field observations to laboratory validation requires meticulously documented and standardized protocols. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for ethnobotanical surveys and subsequent pharmacological investigation:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Field Data Collection and Ethnobotanical Analysis

Ethnobotanical surveys employ systematic approaches to document traditional plant knowledge. A recent study in the Philippines provides a exemplary protocol where researchers conducted modified semi-structured interviews with 252 informants (approximately 10.6% of the total population), reaching data saturation at the 215th interview [23]. This demonstrates appropriate sample size determination in ethnobotanical research. Data collection typically involves:

- Structured and Semi-structured Interviews: Following established protocols like the TRAMIL (Program of Applied Research on Popular Medicine in the Caribbean) guidelines, adapted for digital fluency when necessary [24].

- Plant Collection and Identification: Voucher specimens are collected, identified taxonomically, and deposited in herbariums for future reference [23] [26].

- Documentation of Preparation Methods: Meticulous recording of plant parts used (e.g., leaves 57.4-62.3%), preparation methods (e.g., decoctions 71.8%), and administration routes (e.g., oral 68.4-74.78%) [23] [26].

Statistical analysis of ethnobotanical data typically employs non-parametric tests such as Shapiro-Wilk tests for normality, Mann-Whitney U tests for two-group comparisons (e.g., gender differences), and Kruskal-Wallis H tests for multi-group comparisons (e.g., geographic variation), with significance set at p < 0.05 [23].

Laboratory Validation Protocols

Following the identification of high-priority species through ethnobotanical surveys, laboratory validation employs standardized pharmacological and phytochemical methods:

- Extract Preparation: Plants are typically dried, ground, and extracted using various solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol, water) of increasing polarity to obtain a comprehensive phytochemical profile [24] [25].

- Phytochemical Screening: Preliminary identification of major compound classes (flavonoids, tannins, phenolics, terpenoids) using chemical tests and chromatographic techniques [25].

- Bioactivity Testing: In vitro assays specific to the traditional uses of the plants. For example, plants traditionally used for diabetes would undergo α-glucosidase or α-amylase inhibition assays, while those used for microbial infections would be tested for antimicrobial activity [25].

- Compound Isolation: Bioassay-guided fractionation isolates active compounds using techniques like column chromatography, HPLC, and GC-MS [24] [25].

Comparative Analysis: Ethnobotanical Knowledge Across Regions and Ecosystems

Cross-Regional Comparison of Medicinal Plant Diversity

Ethnobotanical knowledge varies significantly across different geographical regions and ecosystems, influenced by factors such as biodiversity, cultural history, and degree of isolation. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of medicinal plant knowledge across different global regions based on recent ethnobotanical studies.

Table 2: Cross-Regional Comparison of Medicinal Plant Knowledge and Applications

| Region/Country | Community Type | Documented Medicinal Species | Most Represented Plant Family | Notable Bioactive Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philippines (Luzon) [23] | Landlocked agricultural | 93 species across 45 families | Fabaceae (11 species) | Vitex arvensis (UV=1.54, RFC=0.71) |

| Guadeloupe [24] | Caribbean island population | 22 plants with anti-mosquito uses | Not specified | Cymbopogon citratus (FC=93.3%) |

| Ethiopia [26] | Traditional healing community | 115 species across 44 families | Asteraceae (11.3%) | Ocimum lamiifolium (FL=97%) |

| Indian Himalayan Region [4] | Indigenous mountain communities | Significant TEK across sectors | Not specified | Multiple species for climate resilience |

| India [25] | Traditional medicine systems | Focus on Ficus infectoria | Moraceae | Ficus infectoria (flavonoids, tannins) |

This comparative analysis reveals several important patterns. First, the number of documented medicinal species varies considerably, with some communities using as few as 20 species while others utilize over 140, depending on whether they're indigenous or non-indigenous, their level of isolation, elevation, and the extent of modernization [23]. Second, certain plant families consistently appear across different regions as important medicinal resources, particularly Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Asteraceae [23] [26]. Third, quantitative indices successfully identify culturally significant species across diverse regions, demonstrating the robustness of these methodological approaches.

Influence of Geographical and Sociodemographic Factors

Statistical analyses of ethnobotanical data have revealed significant patterns in knowledge distribution:

- Geographic Isolation: A study in the Philippines found significant geographic variation in knowledge (Kruskal-Wallis H = 45.23, p < .001), with informants from Barangay Saoay citing fewer species (5.2 ± 2.1) than those from Barangay Abut (8.4 ± 3.2; Mann-Whitney U, p < .001) and Bacsil (8.1 ± 2.9; Mann-Whitney U, p < .001) [23].

- Sociodemographic Factors: The same study found no significant differences in knowledge across gender (Mann-Whitney U, p = .909), civil status (Mann-Whitney U, p = .641), occupation (Kruskal-Wallis H, p = .564), education (Kruskal-Wallis H, p = .378), or age (Kruskal-Wallis H, p = .173), suggesting complex patterns of knowledge transmission [23].

- Environmental Context: Research has demonstrated that elevation, market access, and healthcare infrastructure influence medicinal plant diversity and knowledge retention across Southeast Asia [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies in Ethnopharmacology

| Reagent/Method | Application | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Survey Tools (Google Forms) [24] | Ethnobotanical data collection | Enables structured data collection while complying with accessibility restrictions |

| Herbarium Specimen Preparation [23] | Plant taxonomic identification | Provides verifiable botanical reference for future studies |

| Solvent Extraction Systems [25] | Phytochemical extraction | Isolates bioactive compounds using solvents of varying polarity |

| Chromatographic Techniques (HPLC, GC-MS, TLC) [24] [25] | Compound separation and analysis | Separates and identifies individual phytochemical constituents |

| Spectrophotometric Assays [25] | Bioactivity screening | Quantifies therapeutic effects (antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory) |

| Cell-based Assay Systems [25] | Mechanism of action studies | Elucidates biological pathways and molecular targets |

Integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Scientific Validation

The "Braiding" Knowledge Systems Approach

A paradigm shift is occurring in ethnopharmacology toward "braiding" Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western science, creating a powerful synergy for drug discovery [3]. Unlike integration, which can imply assimilation of one system into another, braiding suggests that both TEK and Western science retain their distinct integrity while combining to create a stronger, more robust understanding for management action [3]. This approach is particularly valuable in data-scarce regions or for understanding long-term ecological and therapeutic patterns that might be missed in short-term scientific studies [3] [4].

The theoretical foundation for this approach is articulated in a systematic map protocol that defines methodologies for braiding TEK with Western science in managing social-ecological systems [3]. This protocol establishes a framework for classifying braiding methodologies according to their guiding approaches (philosophical stances for collaboration), conceptual frameworks (structured processes that guide braiding), and specific models (tangible tools or outputs) [3].

Validation of Traditional Knowledge through Scientific Methods

Scientific validation of traditional plant uses represents a crucial step in the drug discovery pipeline. A study on Ficus infectoria provides an excellent example of this validation process, where modern pharmacological studies have confirmed its traditional uses for treating diarrhea, ulcers, skin disorders, and diabetes [25]. The research identified specific bioactive compounds—including flavonoids, tannins, phenolics, and terpenoids—that contribute to its documented antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antidiabetic activities [25].

Similarly, in Guadeloupe, an ethnobotanical survey identified 22 plants with traditional anti-mosquito uses, 12 of which had not been previously reported in scientific literature for vector control [24]. This discovery highlights how ethnobotanical approaches can reveal new applications for known plants, expanding their potential therapeutic or public health utility.

Ethnobotanical surveys and ethnopharmacology represent a powerful approach to drug discovery that respects and utilizes Traditional Ecological Knowledge while applying rigorous scientific validation methods. The field continues to evolve methodologically, with new quantitative approaches like the Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI) enabling more systematic comparisons of knowledge across communities and time periods [27].

Significant challenges remain, including the risk of cultural knowledge erosion due to urbanization, land conversion, and changing healthcare preferences [23] [24]. Documenting and preserving this knowledge is therefore essential not only for drug discovery but also for protecting cultural heritage and supporting sustainable resource management [23] [26]. Future research directions should include more clinical trials and mechanism-based investigations to further explore the medicinal value of traditionally used plants [25], while ensuring ethical engagement with knowledge holders through recognition of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities as essential partners in the research process [3].

The convergence of traditional knowledge and modern scientific methods creates a promising pathway for discovering novel therapeutic agents while simultaneously supporting the conservation of both biological and cultural diversity. As the field advances, this integrated approach has the potential to contribute significantly to sustainable healthcare solutions that respect traditional wisdom while meeting contemporary medical needs.

Within the field of ethnobiology, the valid and reliable assessment of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a complex methodological challenge. TEK is a multi-faceted construct, comprising both theoretical knowledge (e.g., plant identification, understanding ecological relationships) and practical skills (e.g., the ability to craft objects from plants, apply medicinal preparations) [28]. Effective validation research requires quantitative indices that can accurately capture these different dimensions. This guide objectively compares prominent methodological approaches for assessing TEK, providing researchers and development professionals with a foundation for selecting and applying robust quantitative instruments in studies aimed at bridging indigenous knowledge and Western science [3].

Comparative Analysis of Quantitative Indices for TEK

A landmark study conducted among 650 native Amazonians provides critical experimental data for comparing eight distinct indices of TEK [28] [29]. The research employed a multi-method approach to collect raw data, which was then transformed into quantitative indices. The table below summarizes the core methodological characteristics of these indices.

Table 1: Comparison of TEK Assessment Indices from an Amazonian Study

| Index Name | Data Collection Method | Type of Raw Data | Dimension Measured | Transformation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple-Choice (Uses) | Structured interview | Knowledge of plant uses (21 plants) | Theoretical Knowledge | Cultural consensus analysis |

| Multiple-Choice (Ecology) | Structured interview | Knowledge of plant biological traits | Theoretical Knowledge | Matching with ecological data |

| Interviews on Uses | Weekly household interviews | Self-reported daily uses of plants | Practical Skills | Frequency and diversity counts |

| Self-Reported Skills | Questionnaire | Self-reported crafting abilities | Practical Skills | Diversity indices |

| Plant Specimen Identification | Direct specimen testing | Ability to identify plant specimens | Theoretical Knowledge | Correct identification score |

| Structured Observations | Direct observation of behavior | Observed practical application of knowledge | Practical Skills | Diversity and proficiency ratings |

Key Experimental Findings on Index Reliability

The study analyzed the associations between the eight indices using Spearman correlations, Chronbach's alpha, and principal components factor analysis to determine reliability [28] [29]. The key experimental findings were:

- Low Cross-Method Correlation: Indices derived from different types of raw data (e.g., a multiple-choice test vs. a practical observation) were weakly correlated (Spearman's rho < 0.5). This indicates that different methods capture distinct, non-overlapping aspects of an individual's TEK [28].

- High Intra-Method Correlation: In contrast, indices derived from the same raw data source (e.g., two multiple-choice tasks) were highly correlated (rho > 0.5, p < 0.001) [28].

- Overall Internal Consistency: Despite the weak correlations between different methods, the suite of eight indices demonstrated relatively high internal consistency (Chronbach's alpha = 0.78). This suggests that while each method taps into a unique dimension, together they contribute to a broader, underlying construct of TEK [28].

The conclusion from this data is that a single method is insufficient to provide a reliable measure of an individual's overall TEK. A robust assessment requires an aggregated measure built from data collected using a variety of methods [28].

Experimental Protocols for TEK Assessment

The following protocols detail the methodologies used to generate the indices compared in the previous section. Adherence to these protocols is critical for ensuring cross-cultural comparability and methodological rigor.

Protocol for Multiple-Choice Tasks (Theoretical Knowledge)

This protocol measures the theoretical dimension of TEK through structured interviews [28].

- Stimulus Selection: Randomly select a subset of plants (e.g., 21) from a comprehensive, pre-established list of culturally significant or useful plants for the local population.

- Interview Administration: In a structured setting, present the participant with each plant name and ask about its potential uses (e.g., for construction, firewood, food, medicine). For each plant, participants may select none, one, or multiple uses.

- Data Recording: Record answers in a matrix, coding affirmative answers as 1 and negative answers as 0.

- Index Construction: Apply cultural consensus analysis or match responses with external ecological data to generate a quantitative score representing the individual's theoretical plant knowledge [28].

Protocol for Interviews on Plant Uses (Practical Skills)

This protocol measures the practical, day-to-day application of plant knowledge [28].

- Sampling Schedule: Conduct weekly household interviews over an extended period (e.g., one year). Visit households during randomly selected three-hour blocks throughout the day (e.g., 7 am to 7 pm).

- Data Collection: During each visit, ask every adult present to list all wild plants they have brought to the household in the preceding 24 hours.

- Data Recording: Document all plant names and their stated uses. Absent adults are coded as missing data to avoid bias.

- Index Construction: Calculate frequency (how often a plant is used) and diversity (number of different plants used) counts from the compiled data to create an index of practical plant use [28].

Protocol for Plant Specimen Identification (Theoretical Knowledge)

This protocol tests the ability to apply theoretical knowledge in a semi-practical context [28].

- Stimulus Preparation: Collect physical specimens or high-quality photographs of a predefined set of local plants.

- Testing Procedure: Present each specimen to the participant one at a time in a standardized setting.

- Data Collection: Ask the participant to identify the plant by its local name.

- Data Recording: Record the response and later code it as correct or incorrect based on expert validation or pre-established ethnobotanical records.

- Index Construction: Calculate the individual's score as the percentage or total number of correctly identified specimens [28].

Visualizing TEK Assessment Methodologies

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz and the specified color palette, illustrate the logical workflow for developing a robust TEK assessment and the relationships between different assessment methods.